Abstract

A distillation system with an ejector for secondary steam utilization can effectively improve energy efficiency. However, the poor performance of the ejector under varying operating conditions makes it difficult for the distillation system to adapt to wide-range operational requirements. To address this challenge, a distillation system using a combined ejector with staged and continuous adjustment is proposed, and its performance and economic feasibility under wide load conditions is analyzed. The results show that when a combined ejector is used—composed of four fixed-structure ejectors with capacities of 6.25%, 12.5%, 25%, and 50%, along with a nozzle needle-adjustable ejector with a capacity range of 0–6.25%—the distillation system can combine the advantages of both staged and continuous adjustment. This system can utilize secondary steam across a load range of 2.53–100%, whereas a distillation system with a single continuously adjustable ejector can only utilize secondary steam within a load range of 40.5–100%. As the load varies from 0 to 100%, the proposed system achieves an average entrainment ratio of 0.525, with an efficiency not less than 50% of the design value over 95.23% of the range. In contrast, the conventional single continuously adjustable ejector has an average entrainment ratio of 0.177, and the distillation system efficiency remains above 50% of the design value for only 25.32% of the range. In a solar-assisted distillation system, the combined ejector improves the coefficient of performance (COP) by over 30%, with a payback period of less than one year. The findings highlight the system’s superior adaptability, efficiency, and economic viability for applications with unstable energy supply.

1. Introduction

Distillation systems are widely used in substance separation processes, such as seawater desalination, fruit juice concentration, and drug purification. The distillation process requires a heat source to heat the solution, enabling the evaporation of light components and achieving separation through phase change. The materials processed in distillation often have specific requirements for heating temperature. For instance, the distillation temperature in seawater desalination is constrained by corrosiveness, while in fruit juice and drug concentration processes, it is limited by the heat sensitivity of the materials (often requiring a distillation temperature no higher than 60–65 °C) [1]. Since the distillation process demands a relatively low heat source temperature, it is well-suited for the application of renewable energy sources, such as solar energy. However, to compensate for the instability of renewable energy usage, a stable heating system (e.g., a biomass boiler) is required as a supplement to ensure continuous production in distillation systems utilizing renewable energy. The steam temperature provided by biomass boilers often exceeds 100 °C, which is significantly higher than the temperature required for the distillation process. A contradiction exists between the supply temperature and the demand temperature, leading to significant irreversible losses. Steam ejector can utilize waste pressure (or waste heat) to pressurize exhaust steam, achieving energy grade matching while recovering the heat from exhaust steam, thereby improving energy utilization efficiency [2].

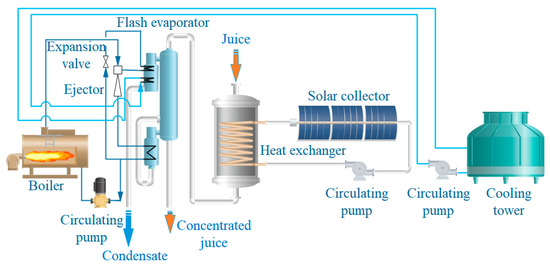

The solar-assisted juice distillation and concentration system, a typical distillation system driven by fuel and renewable energy, is shown in Figure 1. In this system, freshly squeezed juice enters the heat exchanger and is heated by hot water from the solar panel collector in the heat exchanger. The heated juice enters the flash evaporator for concentration. The secondary steam from the flash evaporation enters the condensing unit of the flash evaporator and is condensed into liquid before being discharged. However, when solar energy is insufficient, the boiler needs to provide heat to supplement it. Considering that the boiler steam supply pressure is higher than that required for the evaporation, the heat of the secondary steam from the flash evaporator is partially recovered by using an ejector. The high-pressure steam from the boiler and the low-pressure steam from the condensing unit are mixed by the ejector to become medium-pressure steam that meets the required pressure for heating. Then, it enters the heating unit of the flash evaporator to heat the flash material and condense into saturated liquid. The saturated liquid coming out of the heating unit is divided into two paths. One path is pressurized by the pump and returned to the boiler, and the other path is depressurized by the throttle valve and returned to the condensing unit of the flash evaporator for evaporation, providing cooling for the condensing unit. The excess secondary steam in the system will be condensed by the cooling tower. The heat generated by solar energy has the advantage of being clean, but it also has the disadvantage of poor stability. Therefore, the medium-pressure steam from the ejector is required to have good variable capacity to compensate for the instability of solar heating. As a core component, the ejector is crucial for the energy-efficient and high-performance operation of distillation systems [3]. However, distillation systems (especially those utilizing renewable energy) often experience unstable motive steam pressure [4]. Being the key component for recovering exhaust steam in the system, the ejector is sensitive to boundary conditions; its performance deteriorates sharply when the motive steam pressure deviates from the design conditions. Extensive research has shown that designing geometrically fixed ejector as adjustable-structure ejector can significantly broaden their efficient operating range [5].

Figure 1.

Diagram of solar-assisted juice distillation and concentration system.

Zhang et al. [6] designed an ejector with an adjustable nozzle throat area using a needle to regulate the area, allowing control of the motive steam mass flow rate entering the ejector without changing the motive steam pressure. Their results showed that the distillation system maintained high efficiency, even when operating over a wide load range (50% to 110%). Yang et al. [7] proposed a theoretical model for an ejector with an adjustable nozzle throat area suitable for distillation systems and validated it with experimental data, showing errors between theoretical and experimental values of less than 3%. Based on the calculations, they further analyzed the necessity and performance of using adjustable ejector, providing a theoretical reference for performance research and optimization of adjustable ejector under off-design conditions. Ortega et al. [8] conducted an optimization analysis of a seawater distillation system in a concentrated solar power plant using adjustable ejector. Compared to fixed ejector, the adjustable ejector increased the system’s annual freshwater production by approximately 11.3%. This improvement not only helps the desalination unit operate near rated conditions for extended periods but also significantly reduces the adverse effects of frequent start–stop cycles on equipment performance. Gu et al. [9] used a bellows-driven needle to adjust the nozzle throat area to enhance the operational performance of the distillation system under variable conditions. Simulation results indicated that this adjustable ejector could maintain a high entrainment ratio under motive steam pressure fluctuations: with a critical back pressure of 20 kPa and motive steam pressure varying between 800 and 2000 kPa, the average entrainment ratio was 1.39, significantly higher than that of a fixed ejector. Shahzamanian et al. [10] numerically investigated the effects of the area ratio and nozzle exit position (NXP) on the performance of adjustable ejector in distillation systems under different conditions. The results showed that, compared to fixed ejector, adjusting the NXP improved ejector performance by about 16%, while adjusting the area ratio improved it by about 400%. Wang et al. [11] first proposed an ejector with a self-adaptive nozzle exit position. This device can automatically adjust the NXP according to changes in motive steam pressure, thereby optimizing the ejector’s performance in the distillation system. Numerical results showed that when the NXP was within the range of 43–70 mm, the ejector achieved optimal performance, with the entrainment ratio being up to 35.8% higher than that at a fixed NXP (−30 mm). Yang et al. [12] proposed a theoretical model capable of predicting the performance of adjustable ejector under varying operating and structural conditions. The results demonstrated that when the motive steam pressure changes, using a needle to adjust the nozzle throat area allows the ejector to always operate at the optimal critical state. Within the throat opening range of 80% to 120%, compared to fixed ejector, the adjustable ejector’s performance improved significantly: in the subcritical mode, the entrainment ratio increased by 195.6% and the efficiency by 148.7%; in the critical mode, the entrainment ratio increased by 29.6% and the efficiency by 24.6%.

The aforementioned researchers have all pointed out the advantages of adjustable ejector in distillation equipment. However, the adjustment capability of a single adjustable ejector is ultimately limited [13]. Therefore, using multiple ejectors in parallel is another method to broaden the operating range of ejector. For instance, the use of multiple ejectors in parallel has achieved good research results in refrigeration systems [14]; however, research in distillation systems is scarce. Thus, based on actual meteorological data from Guilin, this paper takes a solar-assisted distillation system as the research object and proposes a combined ejector system comprising several ejectors of different capacities and one adjustable ejector connected in parallel. The fixed-capacity ejectors and their combinations enable stepwise regulation, while the single adjustable ejector with a nozzle needle enables fine regulation between steps. Using an ejector performance calculation model validated with experimental data, the solar-assisted juice concentration distillation system is analyzed. Compared with a conventional single adjustable ejector with a nozzle needle under wide load ranges, the advantages of this combined ejector system are explained from the perspectives of entrainment ratio and system performance coefficient. The research results are of great significance for promoting the application of combined ejector systems.

For the situation of multiple ejectors in parallel, existing studies generally adopt multiple fixed-geometry ejectors or multiple adjustable ejectors in parallel. However, the continuous regulation capability of multiple fixed-geometry ejectors in parallel is limited (stepless regulation cannot be achieved), and multiple adjustable ejectors in parallel will increase the complexity of system control (load change belongs to univariate change, while multiple adjustable ejectors in parallel belong to multivariate regulation), and the equipment cost of the ejector will increase exponentially. This paper proposes a combined ejector that realizes graded regulation through multiple fixed-geometry ejectors of different capacities and their combination, realizes continuous regulation through an adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone needle, and uses the verified ejector performance calculation model to analyze the performance of the proposed combined ejector; based on a typical unstable energy system (solar-assisted juice distillation and concentration system), compared with a conventional single adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone needle under a wide load range, the advantages of the combined ejector are explained from the two aspects of entrainment ratio and performance coefficient. The research results are of great significance for the promotion and application of the combined ejector.

2. Mathematical Model of the System

2.1. Performance Calculation of the System

Before establishing the mathematical model of the system, the following assumptions are made: (1) All heat exchange equipment in the system, including boilers, cooling towers, and flash tanks, is designed with thermal capacity calculated based on maximum production output, ensuring it meets thermal requirements under variable operating conditions. (2) Heat exchangers, flash tanks, ejectors, and all pipelines are well insulated with no heat loss to the surroundings [15]. (3) The power consumption of pumps is negligible compared to the total energy consumption of the system and may be disregarded when calculating the system’s coefficient of performance (COP) [16]. Thus, the COP of the system is as follows:

The thermal load that needs to be provided by the ejector is as follows:

2.2. Model of Solar Collector

The collection capacity of the double-layer glass cover flat-plate solar collector is as folllows [17]:

2.3. Gas Ejector Performance Analysis Model

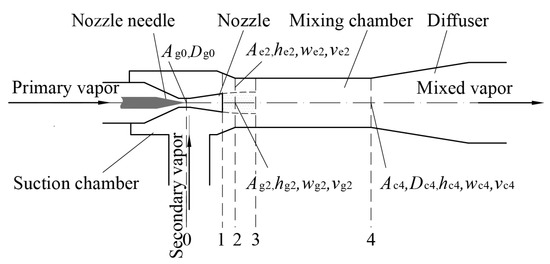

Refer to Figure 2 for the working principle of the vapor ejector: the primary vapor flows through the Laval nozzle, the pressure gradually decreases, the speed gradually increases, reaches the speed of sound at the nozzle throat, and reaches supersonic speed at the nozzle outlet. The secondary vapor also expands and speeds up in the suction chamber. At the nozzle outlet section, the two vapors reach the same pressure and then begin to enter the mixing chamber. After the two streams are mixed and partially pressurized in the mixing chamber, they flow out at a subsonic speed. After the mixing vapor is further decelerated and pressurized by the diffuser, it flows out of the ejector.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of ejector. 0—Nozzle throat cross-section; 1—Nozzle exit cross-section; 2—Inlet cross-section of the mixing chamber; 3—Choking cross-section for the secondary gas; 4—Outlet cross-section of the mixing chamber.

The premise assumptions for model establishment are as follows: (1) The flow inside the ejector is a one-dimensional steady-state flow. (2) The speeds of the primary vapor, secondary vapor and mixing vapor flowing into or out of the ejector are relatively slow, and the kinetic energy can be ignored. (3) The primary vapor reaches the speed of sound at the nozzle throat. (4) The distance between sections 1 and 2 is small, and the gas flow parameters and state parameters on sections 1 and 2 are basically the same. (5) The mixing vapor flows into the diffuser at a subsonic speed.

From the inlet section (cross-section 2) to the outlet section (cross-section 4) of the mixing chamber, we use the momentum equation:

Since the mixing chamber is a cylindrical structure, the flow cross-section 2 and the flow cross-section 4 should satisfy the following geometric relationship:

From the ejector inlet to the ejector outlet, we use the continuity equation:

Similarly, the energy conservation equation should also be established for the inlet and outlet of the ejector:

The entrainment ratio is defined as the amount of secondary vapor that can be induced per unit of primary vapor. This can thus be expressed as follows:

Since the primary vapor reaches the speed of sound in the nozzle throat, the relationship between the primary vapor flow rate and the throat cross-sectional area is as follows:

If the velocity of the secondary vapor reaches the speed of sound at a certain section (section 2) in the mixing chamber, this is called the double-choking mode. Since the primary vapor between section 1 and section 2 does not expand freely but is restricted by the secondary vapor (see Figure 2), the flow section loss coefficient of φ is introduced as follows:

For a vapor that is accelerated from a stagnant state i (i ∈ {g,e,c}) to a certain cross-section j (j ∈ {0,2,3,4}) by its own expansion, the specific enthalpy of primary vapor, secondary vapor, and mixed vapor undergoing an isentropic process can be expressed as follows [18]:

In practical scenarios, the flow of gases is not isentropic, and the isentropic efficiency must be accounted for. Thus, the actual specific enthalpy of primary vapor, secondary vapor, and mixed vapor, when undergoing an isentropic process from state i to cross-section j, can be expressed as follows:

When the specific enthalpy before and after the gas flow process is known, the velocities of the primary vapor, secondary vapor, and mixed vapor, as they transition from stagnation state i to cross-section j, can be determined using the energy conservation relationship:

The specific volume of the primary vapor, secondary vapor, and mixed vapor at cross-section j can be determined using Refprop 10.0 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), based on their specific enthalpy and pressure, as follows:

By applying the continuity equation, the flow area of the primary vapor, secondary vapor, and mixed vapor at cross-section j can be determined as follows:

When calculating the local sound velocity of steam with the nozzle throat state hg0 and p0, if the steam is in a superheated state, it can be directly calculated using NIST Refprop 10.0 [19]:

If the flow is two-phase (common in the case of saturated or lightly superheated vapor in a stagnation state), the local speed of sound is given by the following [17]:

The physical properties required for the calculation process can be obtained by Refprop 10.0 on the premise of knowing hp0 and p0 [19].

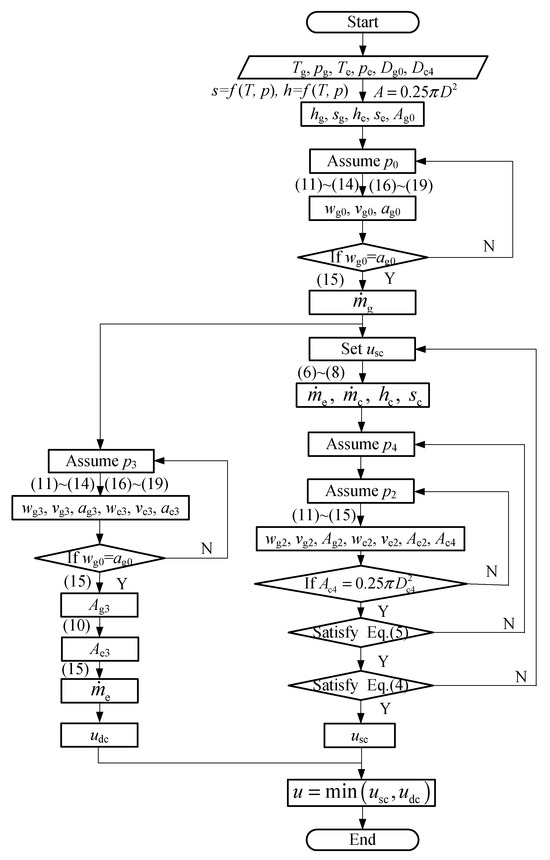

When calculating the performance of the ejector, the known parameters are generally the primary vapor temperature Tg, pressure pg, the secondary vapor temperature Te, pressure pe and back pressure pc, as well as the ejector main cross-sectional dimensions Dg0 and Dc4. What needs to be solved is the entrainment ratio and flow rate. The calculation steps are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart for ejector performance calculation.

2.4. Verification of the Model

An analysis of Section 2.1 reveals that while the heat required for distillation remains constant, the system performance is influenced by the heat input from both the ejector and the solar collector. Given the mature modeling foundation and widespread application of solar collectors in domestic hot water systems, this study focuses specifically on the model validation of the ejector—the key innovative component of this system. The loss coefficients involved in the calculation process are φ = 0.85, ηg = 0.95, ηe = 1, = 0.975, and ηd = 1.18 (the inverse is taken for the unified expression of the formula) [20]. In order to verify the accuracy of the model, the theoretical calculation values of this paper are compared with the experimental research previously conducted by the research group. For details on the experimental procedure and uncertainty analysis, see Reference [21]. The comparison results are shown in Table 1. It can be found that the calculation errors of the entrainment ratio and critical back pressure are within ±12.81% and ±22.54%, respectively. Considering that other factors such as nozzle exit position and mixing chamber length also have an impact on the entrainment ratio and critical back pressure [22,23], this error range is reasonable. The proposed model can correctly analyze the performance of the ejector.

Table 1.

Comparison between calculations and experiments.

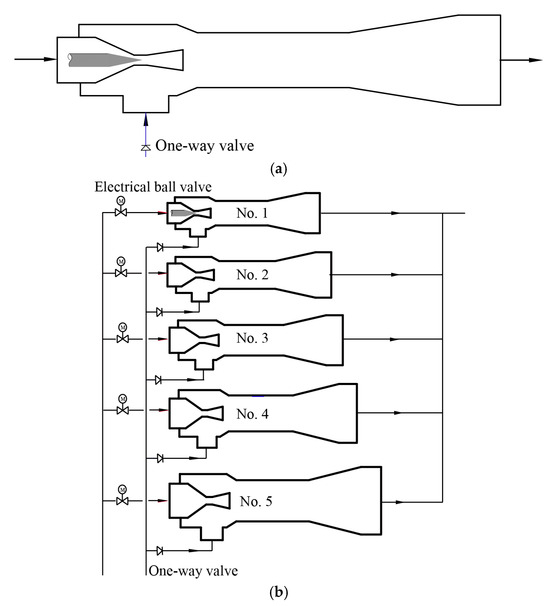

3. Combined Ejector and Single Adjustable Ejector Structure and Adjustment Method

The ejector used in the analysis is used to pressurize steam from 0.0199 MPa (evaporation temperature of 45 °C) to 0.0204 MPa (condensation temperature of 60 °C) [24]. The driving steam is generated by a boiler with a steam pressure of 0.1 MPa (generating temperature of 100 °C). For convenience of comparison, the maximum heating capacity of the two sets of ejectors is 100 kW. The single-stage ejector used for comparison is a conventional adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone needle for variable capacity regulation, with an adaptability range of 0~100 kW (see Table 2). During the regulation process, considering the increase in thermal load, it is necessary to increase the nozzle throat flow diameter through nozzle pointer adjustment to increase the working steam flow rate; however, at this time, due to the reduction in cross-sectional ratio, the entrainment ratio decreases. In order to make use of the ejector which still has energy-saving significance at the maximum thermal load, the design of the single-stage adjustable ejector is based on an entrainment ratio of not less than 0.1 at the maximum load, and the ejector works in a double-choking mode at this time. This approach makes the adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone have a wider adjustment range. In order to reduce costs, the combined ejector consists of five ejectors, including four fixed-structure ejectors with inconsistent capacities (6.25 kW, 12.5 kW, 25 kW and 50 kW) for staged regulation and a small-capacity adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone needle for continuous regulation (capacity of 0~6.25 kW); the specific parameters are shown in Table 3. In order to make the comparison consistent, the No. 1 ejector in the combined ejector adopts the same design basis as the single adjustable ejector; that is, the entrainment ratio is not less than 0.1 at the maximum load (6.25 kW), and it works in a double-choking mode.

Table 2.

The key cross-sectional dimensions and capacity of a single adjustable ejector.

Table 3.

The key cross-sectional dimensions and capacity of the combined ejector.

When the required thermal load changes, the ejector needs to be adjusted to adapt it. For a single adjustable ejector, the nozzle throat diameter can be changed by changing the position of the nozzle cone needle, thereby changing the flow rate of the mixing vapor (as shown in Figure 4a). For the combined ejector, the adjustment method of ejector No. 1 is the same as that of the single adjustable ejector, while ejectors No. 2 to No. 5 are only controlled by the electric ball valve to turn on and off the primary vapor during adjustment (that is, there is only an on and off state, as shown in Figure 4b). Analysis shows that by adopting the combined ejector configuration in Table 4, when the number of ejectors is acceptable, ejectors No. 2 to No. 5 can be reasonably combined to achieve 15 groups of graded adjustments, including 6.25%, 12.5%, 18.75%, 25%, 31.25%, 37.50%, 43.75%, 50%, 56.25%, 62.50%, 68.75%, 75.00%, 81.25%, 87.50%, and 93.75%. With the participation of the No. 1 cone needle ejector with a nozzle, continuous adjustment in the range of 0 to 100% can be achieved.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the combined ejector and the single adjustable ejector. (a) Single adjustable ejector; (b) The combined ejector.

Table 4.

Adjustment strategy for combined ejector in full load range.

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Performance Comparison Between the Distillation Systems with Combined Ejector and Single Adjustable Ejector

The maximum heat supply required by the system is 100 kW, which is equal to the thermal load of the stable juice concentration system. In addition to the heat provided by the solar thermal collection system, the rest is provided by the boiler. A comparative analysis is conducted on the combined ejector and the single adjustable ejector for the solar-assisted juice distillation and concentration system. The analysis is based on a solar heating system that uses a double-layer glass cover flat-plate solar collector with a collection area of 100 m2. The juice before concentration is 23 °C, and the hot water return from the collector is 25 °C (the heat exchange narrow point is 2 °C).

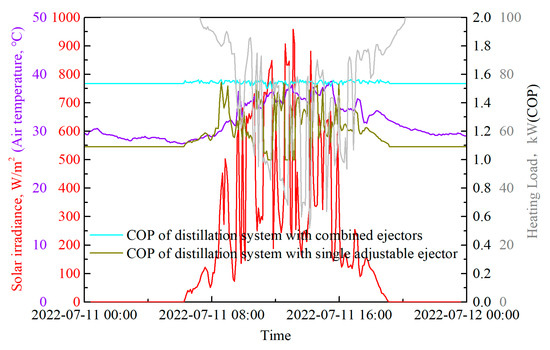

The solar radiation data and temperature data required for the analysis process are derived from the measured meteorological data of Qixing District, Guilin, China. The data of a certain day in summer (11 July 2022) are selected for analysis. The data used consist of 15 min averages and the results are shown in Figure 5. Analysis of Figure 5 shows that when the solar radiation intensity changes, the thermal load required by the vapor ejector in the juice distillation and concentration system will change dramatically. However, from the results, it is found that under the same unstable thermal load requirements, the stability of the performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is significantly better than that of the system using a single adjustable ejector; in terms of COP values, the daily average performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is 1.54, and the daily average performance coefficient of the system using the single adjustable ejector is 1.17. The performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is 31.6% higher than that of the system using the single adjustable ejector.

Figure 5.

Comparison of daily performance coefficients.

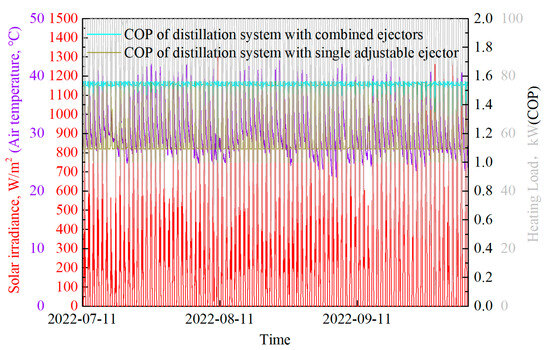

Juice concentration should be a continuous process and has seasonal characteristics. Considering that the maximum benefit of using a solar heating system occurs in summer, further analysis is conducted on the full-season performance coefficient in summer. The solar radiation data and temperature data required for the analysis process are also derived from the measured meteorological data in the Qixing district of Guilin. The data from 11 July 2022 to 5 October 2022 (summer) are selected for analysis, and the results are shown in Figure 6. Analysis of Figure 6 shows that under the same unstable thermal load requirements, the stability of the performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is also significantly higher than that of the system using the single adjustable ejector. In terms of COP values, the daily average performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is 1.54, and the daily average performance coefficient of the system using the single adjustable ejector is 1.16. The performance coefficient of the system using the combined ejector is 32.7% higher than that of the system using the single adjustable ejector. Comparing the summer performance coefficient and the summer single-day performance coefficient, it is found that the performance coefficients are basically the same, which further illustrates that with unstable heating demands, the use of a combined ejector system instead of a single adjustable ejector has the potential to increase the performance coefficient by more than 30%. It is evident that the distillation system utilizing a combined ejector demonstrates a significantly higher COP compared to the system employing a single adjustable ejector, indicating that this innovative system has notable practical implications.

Figure 6.

Comparison of performance coefficients in summer.

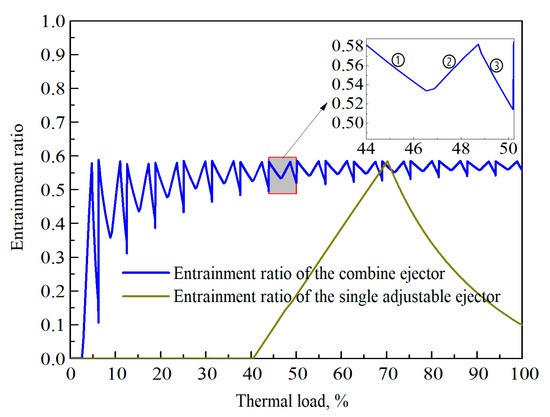

To investigate the reasons for the difference in the COP between the two systems, it is necessary to further discuss the performance of the ejector, which is the component where the two systems differ. In order to make the research conclusion more universal, the value of the thermal load is also converted into a percentage for analysis. By analyzing the entrainment ratio, as shown in Figure 7, for the single adjustable ejector, its effective adjustable range is 40.5–100%; for the combined ejector, its effective adjustable range is 2.53–100%. As the load varies from 0 to 100%, the proposed system achieves an average entrainment ratio of 0.525, with an efficiency not less than 50% of the design value over 95.23% of the range. In contrast, a conventional single continuously adjustable ejector has an average entrainment ratio of 0.177, and the distillation system efficiency remains above 50% of the design value for only 25.32% of the range. It can be seen that while the combined ejector can achieve full thermal load range adjustment, it can also ensure a larger effective adjustable load range. The combined ejector can obtain a higher entrainment ratio in a larger load range.

Figure 7.

Comparison of entrainment ratio over a wide load range.

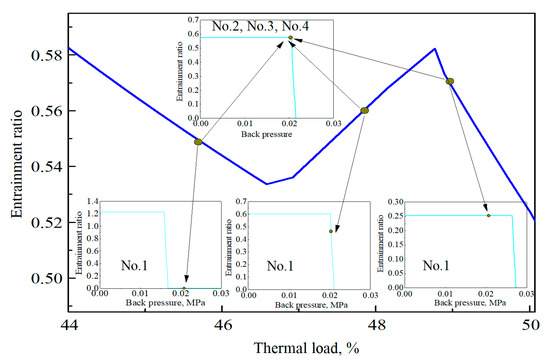

Further analysis shows that the entrainment ratios of the combined ejector and the single adjustable ejector are the same when they perform best. When the working steam pressure is 0.1 MPa (generating temperature of 100 °C), the secondary steam pressure is 0.0096 MPa (evaporation temperature of 45 °C), and the condensing pressure is 0.204 MPa (condensation temperature of 60 °C), no matter what type of ejector is used, the highest entrainment ratio can reach 0.587. This is because when the ejector reaches the optimal entrainment ratio, its operating conditions and area ratio parameters correspond. For ejectors No. 2 to No. 5 in the combined ejector, when the operating conditions and thermal load are consistent with the design values, the optimal entrainment ratio can be achieved. The single adjustable ejector and ejector No. 1 in the combined ejector can also achieve the optimal entrainment ratio by adjusting the nozzle cone needle to the consistent area ratio of ejectors No. 2 to No. 5. However, for a single adjustable ejector operating at the optimal entrainment ratio, when the generating pressure, evaporating pressure and condensing pressure are constant, if the required thermal load increases, the ejector nozzle throat cross-sectional area needs to be increased through cone needle adjustment, at which time the ejector ratio decreases and the ejector operates in a double-choking mode. As the area ratio decreases, its double-choking mode entrainment ratio gradually decreases; if the required thermal load decreases, the ejector nozzle throat cross-sectional area needs to be reduced through cone needle adjustment, at which time the ejector area ratio increases and the ejector operates in a single-choking mode. As the area ratio increases, its single-choking mode entrainment ratio decreases rapidly, and even makes the entrainment ratio negative (working steam is poured into the secondary steam pipe); of course, a one-way valve is often set to avoid the occurrence of a negative entrainment ratio. Since ejector No. 1 of the combined ejector also adopts the nozzle cone needle adjustment method, it can be found in Figure 5 that when the thermal load of the combined ejector changes in the range of 2.53–6.25%, it also has the same entrainment ratio change law as the single adjustable ejector. This is because, for the combined ejector, ejector No. 1 is essentially a scaled-down device of the single adjustable ejector, so it has similar performance. For the combined ejector, the function of ejector No. 1 is continuous adjustment, and the function of ejectors No. 2 to No. 5 is graded adjustment; that is to say, when the thermal load is between 6.25 and 100%, ejector No. 1 is often used in conjunction with other ejectors. Since ejectors No. 2 to No. 5 are not adjustable, when they are adjusted in conjunction with ejector No. 1, the ejector combination will also have a similar entrainment ratio change rule within its corresponding applicable thermal load range. Of course, when any one of the ejectors from No. 2 to No. 5 is added, the combination will not have an entrainment ratio of 0 when working. The typical change rule is shown in the enlarged part in Figure 7. The load range of a typical combination shown in the enlarged diagram of Figure 7 is analyzed (see Figure 8). It is found that when the thermal load range is small (shown in section ①), medium (shown in section ②), and large (shown in section ③), the entrainment ratio has different changing rules as the thermal load increases: when the thermal load is small, the entrainment ratio gradually decreases as the thermal load increases; when the thermal load is medium, the entrainment ratio increases as the thermal load increases; when the thermal load is large, the entrainment ratio gradually decreases as the thermal load increases. Further analysis shows that the typical combination shown in Figure 6 corresponds to the 43.75–50.00 kW situation in Table 4; that is, it is the working combination of ejectors No. 1 to No. 4. For the range with a small thermal load (shown in section ①), ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 work at the optimal operating point, but No. 1 works at an entrainment ratio of 0. If the required thermal load increases, the nozzle cone needle will be adjusted to increase the throat section, and the entrainment ratio will remain at 0; however, the working steam flow rate will increase, while the primary steam and secondary steam flow rates of ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 remain unchanged, which eventually leads to a gradual decrease in the total entrainment ratio. For the range with a medium thermal load range (shown in section ②), ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 work at the optimal operating point, but No. 1 works in the single-choking mode. If the required thermal load increases, the nozzle cone needle will be adjusted to increase the throat section, and the single-choking entrainment ratio will gradually increase (both the primary steam and secondary steam flow rates in ejector No. 1 increase, but that of the secondary steam increases faster), while the primary steam and secondary steam flow rates of ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 remain unchanged, which eventually leads to a gradual increase in the entrainment ratio. For the range with a larger thermal load range (shown in section ③), ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 operate at the optimal operating point, but ejector No. 1 operates in the double-choking mode. If the required thermal load increases, the nozzle cone needle will be adjusted to increase the throat section, the double-choking mode entrainment ratio will decrease, but the primary steam flow rate will increase, while the primary steam and secondary steam flow rate of ejectors No. 2 to No. 4 remain unchanged, ultimately leading to a gradual decrease in the comprehensive entrainment ratio.

Figure 8.

The operating point for each component of the combined ejector within a certain working load range.

4.2. Economic Analysis of the Combined Ejector System for Solar-Assisted Distillation

Although combined ejector demonstrate significant efficiency advantages compared to single adjustable ejector, it is undeniable that they require higher equipment costs. Therefore, further investigation into economic feasibility is necessary. Compared to a single adjustable ejector system, a combined ejector system requires four additional non-adjustable ejectors and their auxiliary components. However, as noted in the literature, non-adjustable ejector is structurally simple and highly reliable in operation. According to recent bidding results from a Chinese companie, the average price of a small ejector is only CNY 2400 [25].

Additionally, the cost of auxiliary equipment required for the combined ejector system is calculated at 50%, and installation labor costs are estimated at 30%. Thus, for a 100 kW heating system, the cost of the combined ejector system increases by CNY 18,720 compared to that of a single adjustable ejector.

Considering steam costs of CNY 200 per ton [26], for a 100 kW heating system operating solely during the three summer months (July to September), the energy savings amount to approximately 254.752 MJ, equivalent to 121 tons of steam. This translates to an annual reduction in operating costs of CNY 24,200. Consequently, the payback period for the additional equipment costs of the combined ejector system is to be less than one year, demonstrating favorable economic benefits.

5. Conclusions

In order to meet the needs of wide load, reduce the requirements for control systems and reduce equipment costs for the distillation system, this paper proposes a combined ejector that realizes graded regulation through multiple fixed ejectors of different capacities and their combination, realizing inter-stage regulation through an ejector with an adjustable nozzle cone needle; based on the verified ejector performance model, the proposed combined ejector is analyzed for performance and compared with an adjustable ejector with a nozzle cone needle. A comparative analysis was conducted on the use of a combined ejector and a single adjustable ejector in a solar-assisted juice distillation and concentration system. The important conclusions obtained include the following:

- (1)

- Using the combination of an adjustable ejector with 0–6.25% range of capacity and 6.25%, 12.5%, 25%, and 50% fixed-capacity ejectors can realize 15 groups of equal differential adjustment, such as 6.25%, 12.5%, 18.75%, 25%, 31.25%, 37.50%, 43.75%, 50%, 56.25%, 62.50%, 68.75%, 75.00%, 81.25%, 87.50%, and 93.75%, with high efficiency, and can realize continuous adjustment in the range of 0~100%.

- (2)

- The effective adjustable thermal load range of the proposed combined ejector for heating is 2.53–100%, while the effective adjustable load range of the single adjustable ejector for heating is 40.5–100%; the combined ejector can enable the vapor ejector to obtain a higher entrainment ratio in a larger thermal load range.

- (3)

- It was found that the COP of the combined ejector was more than 30% higher than that of the single adjustable ejector, both in terms of daily operating performance and summer comprehensive performance.

- (4)

- The payback period for the combined ejector used for the 100 kW solar-assisted distillation system is less than one year.

This study reduces the energy consumption of distillation systems through equipment innovation. Future research should further consider the use of AI algorithms to optimize system control [27]. At the same time, since distillation systems still inevitably rely on fuel for heating, more environmentally friendly fuels should also be incorporated into research [28].

Author Contributions

B.C.: writing—original draft preparation, software, formal analysis; H.C.: funding acquisition, project administration; Z.X.: methodology, data curation, writing—review and editing; W.L.: formal analysis; H.H.: data curation; L.X.: visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation, under grant number 2022GXNSFBA035512.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| A | Area, |

| a | Local sound speed, |

| C | Extended constant pressure heat capacity, |

| COP | Coefficient of performance |

| Specific heat at constant pressure, | |

| D | Diameter, mm |

| Exp. | Experimental value |

| Er | Relative error |

| h | Specific enthalpy, |

| I | Solar radiation intensity, |

| Mass flow rate, | |

| p | Pressure, |

| Q | Heat, |

| Pre. | Current theoretical value |

| s | Specific entropy, |

| Greek letters | |

| T | Temperature, |

| u | Entrainment ratio |

| v | Specific volume, |

| w | Flow rate, |

| β | Coefficient of thermal expansion, |

| γ | Porosity |

| η | Isentropic efficiency |

| μ | Mixing chamber momentum loss coefficient |

| ρ | Density, |

| φ | Flow section loss coefficient |

| Subscripts | |

| amb | Environmental parameters |

| boi | Boiler parameters |

| c | Mixing vapor parameters |

| col | Collector parameters |

| cri | Critical value |

| con | Distiller condensate parameters |

| dc | Double-choking mode parameters |

| dis | Distiller parameters |

| e | Secondary vapor parameters |

| ej | Ejector provided parameters |

| g | Primary vapor parameters |

| L | Saturated liquid phase parameters |

| s | Isentropic process parameters |

| sc | Single-choking mode parameters |

| V | Saturated gas phase parameters |

| wi | Collector return water parameters |

| 0 | Section 0 parameters |

| 1 | Section 1 parameters |

| 2 | Section 2 parameters |

| 3 | Section 3 parameters |

| 4 | Section 4 parameters |

References

- Fingas, R.; Haida, M.; Smolka, J.; Croci, L.; Bodys, J.; Palacz, M.; Besagni, G. Experimental Analysis of the R290 Variable Geometry Ejector with a Spindle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, C.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. A Visual Mass Transfer Study in the Ejector Considering Phase Change for Multi-Effect Distillation with Thermal Vapour Compression (MED-TVC) Desalination System. Desalination 2022, 532, 115722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, S.; Deymi-Dashtebayaz, M.; Tayyeban, E. Parametric Investigation and Performance Optimization of a MED-TVC Desalination System Based on 1-D Ejector Modeling. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 288, 117131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Xue, H.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, L. Full-Operating-Condition Performance Improvement Strategy and Optimal Design of a Two-Stage Ejector with Auxiliary Secondary Flow for MED-TVC Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 260, 124957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, J. Coupling Optimization Design of Adjustable Nozzle for a Steam Ejector. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 252, 123550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, L.; Shen, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, K. Analysis of Adjusting Method for Load Performance of TVC-MED Desalination Plant. Desalin. Water Treat. 2013, 51, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, S.; Zhou, S.; Mu, X.; Zhang, K. Research for the Adjustable Performance of the Thermal Vapor Compressor in the MED–TVC System. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Delgado, B.; Cornali, M.; Palenzuela, P.; Alarcón-Padilla, D.C. Operational Analysis of the Coupling between a Multi-Effect Distillation Unit with Thermal Vapor Compression and a Rankine Cycle Power Block Using Variable Nozzle Thermocompressors. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Yin, X.; Liu, H. Performance Investigation of an Auto-Tuning Area Ratio Ejector for MED-TVC Desalination System. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 155, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzamanian, B.; Varga, S.; Soares, J.; Palmero-Marrero, A.I.; Oliveira, A.C. Performance Evaluation of a Variable Geometry Ejector Applied in a Multi-Effect Thermal Vapor Compression Desalination System. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H. Design and Numerical Investigation of an Adaptive Nozzle Exit Position Ejector in Multi-Effect Distillation Desalination System. Energy 2017, 140, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, K.; Shen, S. Research on Critical Mode Transferring Characteristics for Adjustable Thermal Vapor Compressor in MED-TVC System. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 266, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Kong, F.; Liu, G.; Wang, L.; Lai, Y. Synergistic Effect of Adjustable Ejector Structure and Operating Parameters in Solar-Driven Ejector Refrigeration System. Sol. Energy 2023, 250, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tian, H.; Liu, K.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, X.; Shu, G. Optimum Pressure Control with Three Controllable Ejectors of a CO2 Multi-Ejector Refrigeration System. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 157, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, C.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Chong, D.; Yan, J. Theoretical Analysis of Ejector Refrigeration System Performance under Overall Modes. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, X.; Xi, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Z. Thermodynamic Analyses of Ejector Refrigeration Cycle with Zeotropic Mixture. Energy 2023, 263, 125989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Yan, S.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, B.; Shen, Q.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y. Study on Thermal Performance of Flat Plate Solar Collector with double-layer. Sol. Energy 2020, 318, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, J.; Ge, J.; Lu, W.; Zheng, L. A Cylindrical Mixing Chamber Ejector Analysis Model to Predict the Optimal Nozzle Exit Position. Energy 2020, 208, 118302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.L.; Lemmon, E.W.; Bell, I.H.; McLinden, M.O. The NIST REFPROP Database for Highly Accurate Properties of Industrially Important Fluids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 15449–15472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chen, H. Design of Cylindrical Mixing Chamber Ejector According to Performance Analyses. Energy 2018, 164, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Chen, H.; Li, J.; Jin, Y. Experimental Comparison of Critical Performance for Variable Geometry Ejectors with Different Mixer Structures. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Hu, Q.; Yu, M.; Han, Z.; Cui, W.; Liang, D.; Ma, H.; Pan, X. Numerical Investigation on the Influence of Mixing Chamber Length on Steam Ejector Performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 174, 115204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, M. Influence of Operating Conditions on the Optimal Nozzle Exit Position for Vapor Ejector. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 210, 118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. Chapter 4—Food Flavor Additives. In Food Additives; China Light Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2019; p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- China National Offshore Oil Corporation. Announcement of Bidding Results for 4 Steam Jet Pumps in Operation Department 3 of Daxie Petrochemical Zhoushan Plant. Available online: https://www.bidcenter.com.cn/news-360943299-1.html (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zhang, H. Chapter 3—Feasible Technologies for Ammonia Nitrogen Pollution Prevention and Control—Case Studies. In Compilation of Feasible Technical Cases for Ammonia Nitrogen Pollution Prevention and Control; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Der, O.; Manjunath Patel, G.C.; Giasin, K.; Ercetin, A. State-of-the-Art Review of Energy Consumption in Machining Operations: Challenges and Trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q. A Review of Energy Consumption in the Acquisition of Bio-Feedstock for Microalgae Biofuel Production. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).