1. Introduction

To meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) related to accessibility to nutritious and healthy food, the agricultural sector plays a key role. Between 2000 and 2021, global vegetable production increased by 68%, reaching a total volume of 1.15 billion tons in 2021 [

1]. The most produced vegetable was tomato (189 million tons in 2021), followed by onion (107 million tons) and cucumber (93 million tons) [

2]. The countries with the highest tomato (

Solanum lycopersicon) production were China (67,538,340 tons), India (21,181,000 tons), and Turkey (13,095,258 tons). In South America, tomato production reached 7.27 million tons, while Honduras produced 75,972.12 tons, ranking 85th worldwide [

3]. In addition to chemical methods for pest and disease management, one of the main control activities is crop exploration, which enables the identification of both the occurrence and type of pests and diseases, allowing appropriate control measures to be implemented.

Robots are increasingly being adopted in the agricultural sector as part of innovation processes aimed at improving productivity. Farmers face constant challenges in crop production for food supply. Agriculture must continue to evolve and innovate to achieve higher yields and increase production. Despite global advances, the seed production sector continues to face difficulties; however, implementing control systems can lead to the better utilization of growing plants [

4]. With the development of new technologies, the agricultural industry has begun integrating robotics and automation to enhance productivity and crop protection [

5]. The inclusion of robotics in agriculture contributes to sustainability by enabling more accurate and efficient farming practices. Through robotic systems, real-time data on crop conditions can be collected, helping farmers design better strategies for harvesting and management [

6]. Innovation in agriculture is crucial to improving early detection and control of leaf diseases, thereby preventing productivity and economic losses [

7]. Moreover, robotics helps sustain plantations affected by labor shortages and the lack of specialized expertise. The goal of plant disease detection is to prevent, control, and eliminate damage caused by pathogens and environmental stressors, thus protecting plant health and ensuring crop safety. Early detection allows for timely interventions that minimize disease spread and reduce crop losses [

8].

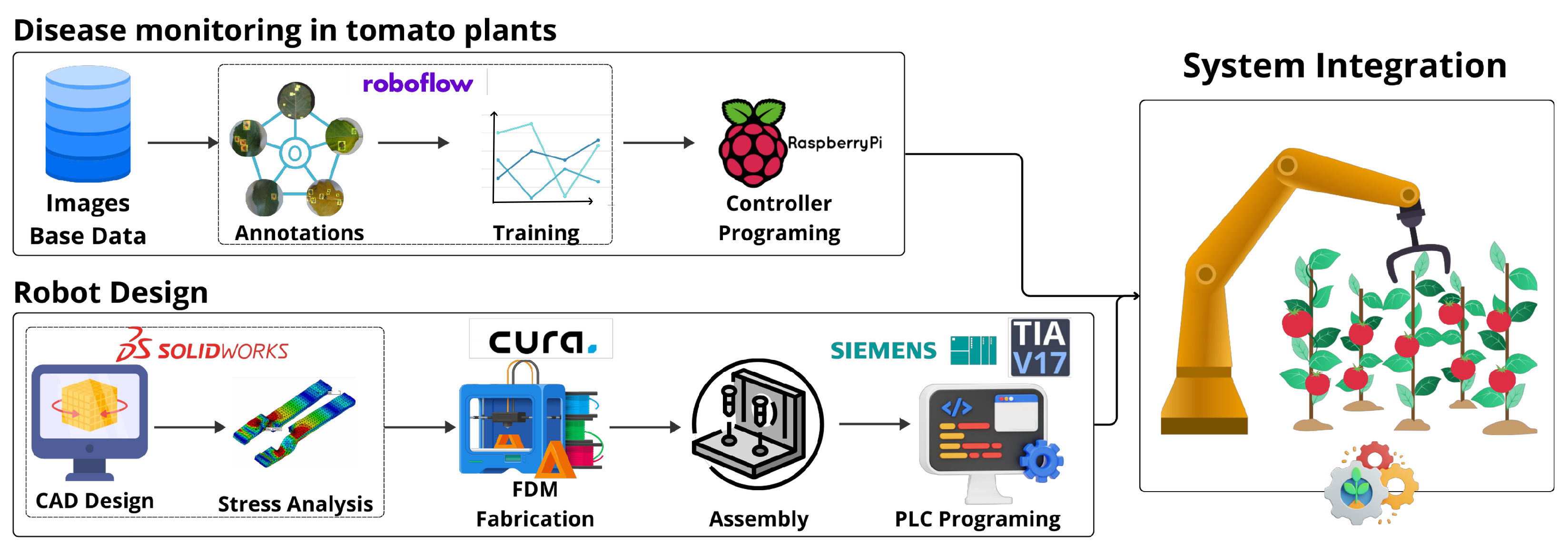

We have developed a robot capable of detecting the health condition of plant leaves by integrating advanced technologies, as shown in

Figure 1. The early and accurate detection of health problems—such as diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and pest infestations—is essential to prevent their spread and maintain crop vitality. The robotic arm, with its multiple degrees of freedom, provides precise and controlled movements, offering a stable platform crucial for monitoring tasks that require high positional accuracy. The robot is equipped with a custom-designed end-effector that, together with its structural stability, enables the collection of targeted data for analysis.

An artificially intelligent robot designed for leaf disease detection offers significant advantages to the agricultural industry, which remains largely inefficient in terms of labor and heavily dependent on fertilizers without precise data on plant health. With this robot, it becomes possible to detect diseases at early stages and take appropriate corrective measures for effective crop management. In addition to reducing the use of pesticides, the system provides improved control over crop conditions, resulting in higher-quality agricultural production. This innovation eliminates the need for manual inspections, saving time and resources while promoting healthier plant growth and the production of safer, higher-quality food.

3. Neural Network Methodology

This study proposes a neural network-based methodology for the detection of diseases in tomato plant leaves, integrated within a robotic inspection system. The workflow, illustrated in

Figure 2, consists of five main stages: data collection, image annotation, model training, validation, and deployment.

The proposed methodology follows a supervised learning approach, in which the neural network learns from labeled images of healthy and diseased tomato leaves. The process includes data acquisition, preprocessing, model development, validation, and testing. Each stage is designed to ensure reproducibility and optimize detection performance for integration into the robotic end-effector system.

3.1. Data Collection on Diseases in Tomato Plants

The dataset used in this research consisted of 7864 original images of tomato plant leaves, including both healthy and diseased samples. The collected images represent eight main pathologies: Early Blight, Late Blight, Leaf Mold, Mosaic Virus, Septoria Leaf Spot, Spider Mite Damage, Leaf Miner Damage, and Yellow Leaf Curl. Data collection was conducted using publicly available datasets from the Roboflow Universe platform, specifically designed for plant disease detection tasks.

Figure 3 displays representative images of diseased tomato leaves from the dataset, illustrating the diversity among the selected diseases.

3.2. Image Annotation

Image annotation was performed manually using Roboflow’s integrated labeling tools. Each lesion or diseased region was enclosed with bounding boxes and labeled according to its respective disease class. Expert verification ensured labeling accuracy and reduced bias. The images were automatically oriented and resized to 640 × 640 pixels prior to preprocessing and training.

Figure 4 shows how only the region of interest corresponding to the affected leaf area is selected during labeling.

3.3. Training

During preprocessing, data augmentation techniques were applied to increase dataset diversity and model generalization. Through Roboflow’s pipeline, each image generated three augmented variants, producing a total of 16,417 images for training (87%), 1573 for validation (8%), and 786 for testing (4%). Augmentation techniques included brightness variation between −30% and +30%, scaling, mosaic composition, horizontal flipping, and HSV adjustments.

The YOLOv5s model was trained using the default Ultralytics configuration with the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer, a learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.937, and weight decay of 0.0005. Training was executed for 200 epochs, with a batch size of 16 and early stopping enabled. These procedures ensured robust feature extraction and convergence stability across the dataset.

3.4. YOLOv5 Architecture

The YOLOv5 architecture comprises four principal modules: the backbone, neck, head, and detection layers. The backbone extracts hierarchical spatial features, while the neck aggregates multi-scale features using PANet connections. The head performs dense predictions to generate bounding boxes and class probabilities. The model employs the CIoU loss function for bounding box optimization and outputs confidence scores per class. YOLOv5s was selected for its lightweight structure (7.2 M parameters), real-time performance, and high detection accuracy, making it ideal for integration with robotic systems for plant health monitoring.

3.5. Validity and Reproducibility

It can be mentioned that the study presents a clear and detailed methodology for detecting plant diseases using deep transfer learning. The methods used seem to align with the study’s objective and are described with enough detail to allow study replication. However, there is no information on the validity of the data used in the study, which could impact the results. In general, more information is required to fully assess reproducibility and validity [

35].

The suggested model is addressed using data augmentation methods and capturing images in different environments and conditions. Reproducibility and validity are addressed through data augmentation techniques, careful selection of image data, and evaluation methods such as confusion matrices. However, it does not explicitly provide specific reproducibility algorithms or codes [

17].

A detailed description of the proposal and the experimental design used is provided, indicating measures taken to ensure the internal and external validity of the study. Sufficient details about the study proposal and the experimental design are given to enable other researchers to reproduce it. Simulation and experiment results are also presented, and both can be replicated using the same manipulator robot and experimental setup. Overall, while the study presents promising results, further research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of the proposal and assess its applicability in various contexts [

36].

The three provided research studies bolster and validate the current project centered on the development of a neural network for the detection of diseases in tomato plants. The dedicated focus on reproducibility, the implementation of data augmentation methods, and the detailed description of experimental designs in the mentioned studies support the robustness of the methodology employed in the current project.

4. Robotic Arm Architecture

For the development of the robotic arm prototype, the main challenge was the extension of the robot to adapt its height with two prismatic axes. We mainly used SolidWorks 2024 CAD software for the development of parts and necessary analysis for the final development of the robot arm prototype. The final prototype has five rotational axes and prismatic ones, for a total of seven DOF, which will give it vast mobility to reach complex positions for its final use.

4.1. CAD Design

The rotational actuators are fundamental for the robot’s movements, and they have a planetary gear mechanisms, as shown in

Figure 5, with three different sizes. The actuators contain a gear ratio corresponding to their size: The large actuator is 1:108, the medium actuator is 1:76.5, and the small actuator is 1:64.4.

The rotational actuators provide movement in degrees as a measurement unit on all five rotational axes. Each one has a rotational displacement of less than 360 degrees of movement in order not to exceed the limits proposed in the final design of the robot body.

The planetary gear transmission ratio is defined in Equation (

1), where the relationship between the ring gear, sun gear, and carrier angular velocities is expressed:

where

R—number of teeth on the ring gear;

S—number of teeth on the sun gear;

—angular velocity of the planetary carrier;

—angular velocity of the ring gear;

—angular velocity of the sun gear.

The prismatic extension mechanism, shown in

Figure 6, consists of two main parts. The first part includes a NEMA 17 stepper motor mounted on the lower section, which remains fixed. Its shaft drives an 8 mm diameter, 60 mm long lead screw connected to a trapezoidal nut. This nut is attached to the second, movable section that performs the extension motion through the nut’s linear travel along the lead screw. The model also incorporates four smooth rods, each measuring 8 mm in diameter, positioned at the corners to provide additional rigidity and structural stability to the robot.

The prismatic extension mechanism is integrated into two segments of the robot. The first prismatic joint is positioned between rotational axes one and two, providing a maximum extension of 24 mm. The second prismatic joint is located between rotational axes two and three, allowing a maximum extension of 16.5 mm. Together, these two prismatic mechanisms provide a total combined extension of 40.5 mm for the robotic model.

The drive power

P of a worm screw consists of the sum of three main components, as expressed in Equation (

2):

where

is the power required to move the material horizontally,

is the power required to drive the screw in freewheeling operation, and

is the power required when the screw operates on an incline.

The total power required to drive the screw conveyor can, therefore, be determined by summing the individual power components, as shown in Equation (

3):

which can be further simplified into Equation (

4):

where

—power required to move the material horizontally;

—power required to drive the screw in freewheeling operation;

—power required when the screw operates on an incline;

Q—flow rate of the transported material (t/h);

H—height of the installation (m);

D—diameter of the conveyor casing (m);

—resistance coefficient of the transported material;

L—length of the screw (m).

Once the rotational and prismatic mechanisms were calculated, the necessary actuator measurements were obtained to design the robot’s structural body. The manipulator comprises five rotational actuators, two prismatic mechanisms, and three connecting links. Each component of the robot’s housing was parametrically designed in CAD SolidWorks to ensure geometric consistency and optimal performance. Additionally, motion and load simulations were performed to analyze the kinematic behavior and verify the structural efficiency of the design.

Figure 7 illustrates the 7-DOF robotic configuration, highlighting the reference coordinate frames assigned to each joint according to the Denavit–Hartenberg (D–H) convention. The model integrates five revolute joints (R) and two prismatic joints (P), forming a 5R + 2P redundant manipulator. The coordinate axes are color-coded as follows: the

X-axis in blue, the

Y-axis in red, and the

Z-axis in green. These reference frames serve as the foundation for defining the robot’s kinematic parameters and transformations, summarized in

Table 1. The Denavit–Hartenberg parameters for the 7-DOF manipulator are summarized in

Table 1.

4.2. Motion Analysis

The final robotic model was submitted to a motion study to be analyzed with a simulation involving all its segments and actuators working in a constant movement routine, and the final assembly robotic model was analyzed. The motion study is needed to simulate real-time conditions that can have an effect on its kinematics; elements such as gravity, contact forces, weight, inertia, torque, energy consumption, velocity, acceleration, angular velocity, and linear displacement were included in this study. It is necessary to use this procedure to verify and rectify elements that can affect the functionality of the model in real-life situations.

4.3. Stress Analysis

A stress analysis was performed to evaluate the deformation produced by high loads applied to the robot structure and to determine the safety factor of each component. Since the robot is fabricated using ABS plastic, which is lightweight but less rigid, it was necessary to ensure that all components operate within safe stress limits under working conditions. This study focused on both stress distribution and displacement behavior to guarantee an adequate safety margin and prevent mechanical failure during operation, as shown in

Figure 8.

The simulation considered all actuators operating simultaneously, reaching two specific positions and returning to their initial configuration. This procedure provided the necessary data to verify the mechanical integrity of each part and confirm that the assembly could safely sustain the expected loads.

The safety factor must be greater than one; the higher the value, the greater the resistance of the part to stress under operational conditions. Conversely, a safety factor equal to or below one indicates that structural failure will occur when the applied load reaches the studied stress value.

An adaptive mesh refinement based on the h-method was applied, performing three successive iterations to increase element density in regions of high stress concentration. This adaptive process improved numerical accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. The final mesh reached convergence stability, confirming that the calculated Von Mises stresses were independent of further refinement.

The factor of safety (FOS ) is determined using Equation (

5), which relates the material yield strength to the maximum Von Mises stress:

where a higher

value indicates a more robust and reliable structure.

4.4. Materials and Printing Parameters

The robotic prototype was manufactured using the fused deposition modeling (FDM) technique, commonly known as 3D printing. Two 3D printers were employed during the fabrication process, specifically the Ender 3 V2 and Ender 3 S1 models. The material selected for the printing process was acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), chosen for its physical properties, high rigidity, and resistance to elevated temperatures, which make it suitable for mechanical components that require durability and stability.

The fabrication process began with converting each of the CAD models into STL file format to ensure compatibility with the slicing software. The 3D processing software used was Ultimaker CURA version 5.3.0, where the general printing parameters were configured for both printers. Each model was processed under a unified print profile, with adjustments made based on the geometric complexity and function of the part. The main parameters included a layer height ranging between 0.10 mm and 0.20 mm, depending on the size of each component. Smaller parts required finer layers to preserve detail, while larger ones were printed with thicker layers to reduce manufacturing time. The number of external walls was adjusted to improve rigidity and achieve a better surface finish, avoiding visible internal filling patterns.

The infill density was set between 20% and 40%, depending on the mechanical function of the component. Parts subjected to greater stress were assigned higher infill percentages to increase internal strength. A horizontal expansion compensation was also performed to calibrate the material’s thermal behavior. A 20 mm cube test printed in ABS revealed a dimensional expansion of +0.12 mm, which was corrected by applying a compensation value of −0.12 mm in the slicing configuration. This adjustment ensured dimensional accuracy in all printed components.

After configuration, each part was prepared and sliced individually in CURA, generating its corresponding G-code file containing print time and material consumption data. The files were transferred to a microSD card for direct use in the printers. Before each printing session, bed leveling was performed manually to guarantee adhesion and uniform layer deposition. Finally, each part was printed using the configured parameters, producing high-quality components with excellent surface finish, structural integrity, and dimensional precision suitable for robotic assembly and mechanical testing.

4.5. Control System Configuration

The controller represents one of the most critical components of the robot, as it governs the operation of all electrical elements, particularly the stepper motors, which are essential for robot actuation and motion control. For this project, two Siemens Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) were used: SIMATIC S7-1200 CPU 1214 DC/DC/DC (firmware version 4.2) and SIMATIC S7-1200 CPU 1212 DC/DC/DC (firmware version 4.2).

The use of two controllers was necessary due to the configuration of the pulse train output (TPO) channels. Each TPO function consumes two physical outputs, one for the pulse signal and one for the direction signal, as shown in

Figure 9. The CPU 1214 controller provides four TPO configurations, which utilize all its physical outputs, while the CPU 1212 offers three configurations, also occupying all available outputs. To interface with these TPO signals, external drivers capable of processing 24 V DC logic were required.

The drivers used to control the bipolar NEMA 17 stepper motors were DM542 units, designed to handle supply voltages between 20 V and 50 V DC and a maximum current of 4.2 A per motor. All control signals were configured as PNP-type, with a shared neutral reference between the PLCs and the drivers at 24 V DC.

Figure 10 illustrates the blocks diagram for the connection between the PLC controllers and the DM542 driver.

The programming of Siemens S7-1200 PLCs (Siemens AG, Nuremberg, Germany) was carried out using the TIA Portal V17 software environment. The developed program integrates both PLCs, a KTP700 (Siemens AG, Nuremberg, Germany) Basic HMI panel for manual parameter control and an SM1223 expansion module (Siemens AG, Nuremberg, Germany) providing additional digital I/O channels. Each PLC and the HMI were assigned unique IP addresses within the same network segment to enable seamless communication.

Data exchange between the two PLCs was implemented using the Profinet S7 communication protocol (PUT/GET), a protocol exclusive to Siemens S7 devices. The S7-1214 controller was designated as the primary unit, hosting all robot control logic. This includes manual and automatic operation modes, homing routines, global resets, and movement commands. The operator interacts with these functions via the KTP700 HMI panel, which provides a user-friendly graphical interface.

A critical part of the programming involved the configuration of the TPO outputs. Within the TIA Portal, this is achieved using the Technology Objects block, where motion parameters, such as the number of output pulses, are defined. For synchronization, each DM542 driver was configured to match the PLC parameters, with all motors set to 6400 steps per revolution. Once the technology objects were configured, motion control instructions such as Speed, Halt, Reset, Jog, and Absolute Move were implemented, along with a homing function.

The same configuration was applied to the S7-1212 controller to control the remaining three motors of the robot. Communication between both controllers was established through the PUT and GET function blocks. Four bytes of data were assigned to each block, enabling efficient bidirectional communication. The GET instruction reads data from the S7-1212 and stores it in memory bits accessible to the main controller, while the PUT instruction transmits control data from the S7-1214 to the S7-1212. This configuration allows the centralized control of all robot movements and parameters through the HMI interface.

4.6. End-Effector Design and Integration

The structure was printed in Polylactic Acid (PLA) due to its favorable properties for rapid prototyping, including rigidity, dimensional stability, and ease of processing. The design not only ensures mechanical robustness but also reflects a modern and functional aesthetic suited for integration with the 7-DOF robotic manipulator.

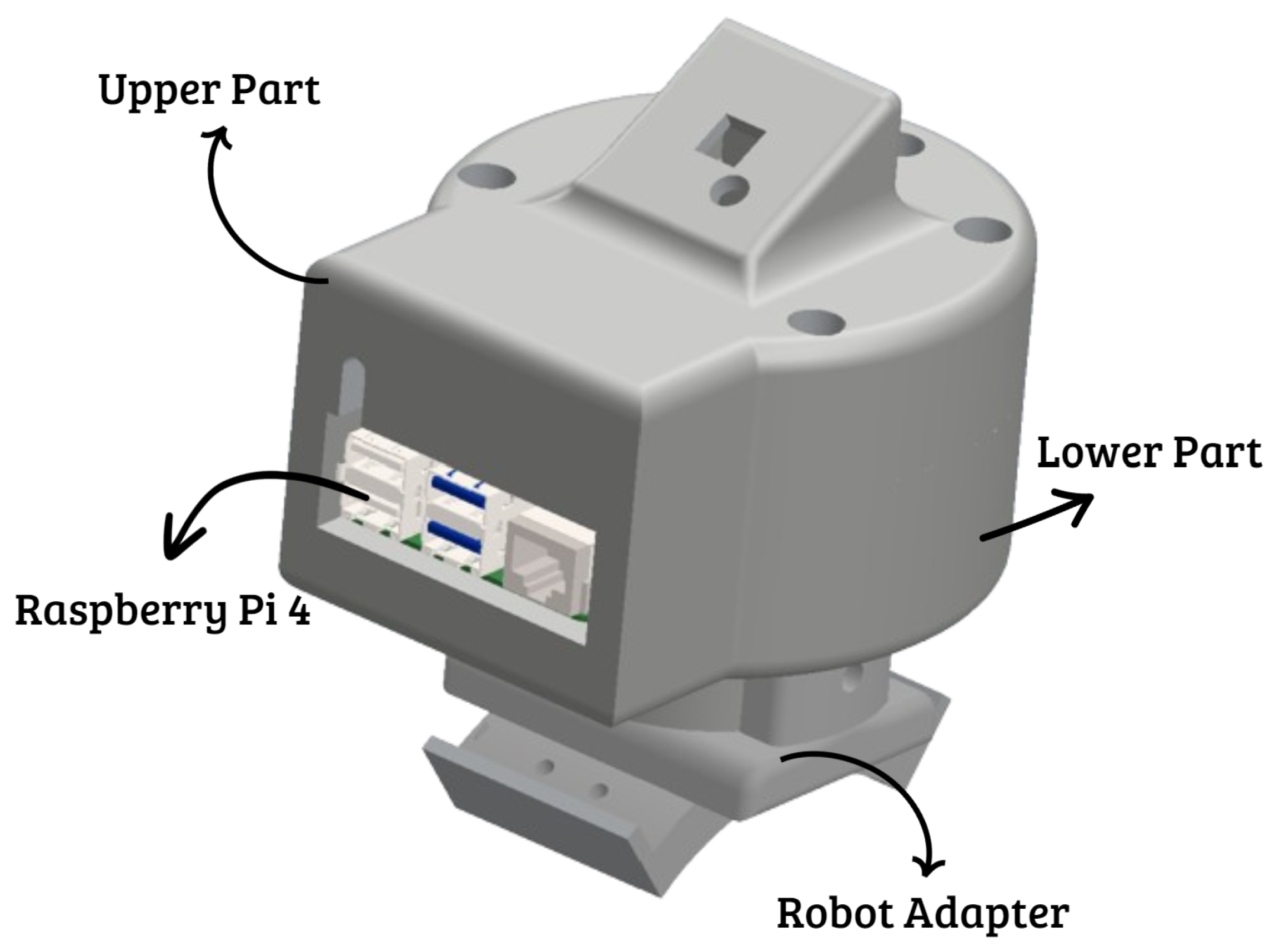

The end-effector integrates a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B microcomputer, manufactured by Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK as its primary processing unit, as shown in

Figure 11. This board features a 1.5 GHz 64-bit quad-core ARM Cortex-A72 CPU, 4 GB of LPDDR4 RAM, and support for hardware acceleration via its VideoCore VI GPU. These characteristics allow the embedded execution of the YOLOv5 neural network model without the need for an external computing unit. Additionally, the system includes an official 8 MP Raspberry Pi Camera Module v2 positioned at the upper section of the effector, providing real-time image acquisition for disease detection and visual monitoring.

The Raspberry Pi 4 is powered through a regulated 5 V DC supply and communicates wirelessly via Wi-Fi 802.11ac with the main control network, enabling remote data transfer and synchronization with the robot’s supervisory system. The integration of USB 3.0 ports allows the direct connection of additional peripherals, such as solid-state drives (SSDs) for dataset storage or external accelerators like the Coral USB TPU, should higher inference speeds be required.

Mechanically, the end-effector features a compact housing designed to protect electronic components from vibration and heat dissipation during operation. The internal architecture provides isolated compartments for the power electronics, camera wiring, and processing board, ensuring electromagnetic compatibility and operational safety. The effector is mounted on the last link of the manipulator using a standardized M8 flange adapter, ensuring stable coupling and precise alignment of the optical axis with the plant observation area.

This combination of embedded computing, computer vision, and mechanical stability enables advanced data processing directly at the end-effector level, allowing real-time leaf disease detection and analysis. As a result, the robotic system achieves greater autonomy, responsiveness, and adaptability in agricultural monitoring tasks.

5. Results

5.1. Neural Network Performance

This section presents the main results obtained from the implementation of the neural network for disease detection in tomato leaves. The analysis focuses on fundamental evaluation metrics such as accuracy, mean average precision (mAP), and real-time detection capability, providing a comprehensive overview of the model’s performance and learning behavior across different testing stages.

During the initial testing phase, a pilot experiment was conducted using 25% of the total dataset, comprising 1950 images of tomato plant leaves affected by different diseases. This subset was used to perform an early assessment of the model’s ability to classify and detect pathological features in leaves. In this preliminary evaluation, the network achieved an accuracy of 64.2% and an mAP of 56.1%, as shown in

Figure 12b. These values established the baseline performance for the system.

Subsequently, in the final evaluation phase, the model was trained using the complete dataset consisting of 7864 images, including both diseased and healthy leaves. This extended training led to a significant improvement, yielding an overall accuracy of 90.2% and an mAP of 92.3%, as illustrated in

Figure 12a. The improvement demonstrates the importance of dataset expansion and iterative retraining, confirming that larger and more diverse datasets enable the model to generalize more effectively to real-world conditions.

Figure 12 shows representative examples of detections for each of the eight tomato diseases. Each condition presents distinctive visual characteristics that the model successfully identifies. Early Blight (

Alternaria solani) produces concentric dark lesions leading to premature defoliation; Late Blight (

Phytophthora infestans) generates water-soaked lesions typical of this pathogen; Leaf Miner Damage results from insect larvae forming tunnels in the leaf tissue; Leaf Mold (

Fulvia fulva) manifests as yellow-brown patches on the leaf surface. Mosaic Virus infections cause irregular green-yellow mottling, whereas Septoria Spot (

Septoria lycopersici) appears as numerous small dark lesions. Spider Mite Damage is characterized by chlorotic stippling and discoloration, while Yellow Leaf Curl Virus induces pronounced curling and yellowing of foliage. These results confirm that the trained model accurately recognizes both fungal and viral pathologies, providing a reliable tool for automated disease monitoring in tomato crops.

As observed in

Table 2, the model achieved high precision across all evaluated conditions. Notably, diseases such as Leaf Miner Damage and Leaf Mold reached 97% accuracy, while Spider Mite Damage achieved an outstanding 99%. Yellow Leaf Curl also exhibited strong recognition performance at 94%. These results demonstrate the model’s ability to distinguish between diverse morphological patterns with minimal misclassification.

In contrast, slightly lower accuracies were observed for Mosaic Virus (86%) and Early Blight (87%), likely due to their visual similarity to other foliar lesions and overlapping features in the dataset. However, even in these cases, the detection performance remained within acceptable limits for agricultural diagnostic systems. Overall, the results confirm that the YOLOv5 network efficiently identifies and classifies a broad spectrum of tomato leaf pathologies, establishing a solid foundation for real-world implementation in precision agriculture.

The performance of the YOLOv5 model was analyzed through the evaluation of its training and validation metrics, as shown in

Figure 13. The results demonstrate a consistent decrease in loss values throughout the training process, confirming appropriate convergence behavior. Both training and validation box, class, and distribution losses followed similar descending trends, indicating that the model effectively learned to generalize from the dataset without exhibiting overfitting.

Regarding precision and recall, the model achieved balanced and high performance, reaching precision values close to 0.90 and recall values around 0.85. This balance suggests that the trained network maintains low false-positive and false-negative rates, which is crucial for reliable disease detection in tomato leaves. Furthermore, the mean average precision (mAP) achieved at different thresholds reveals strong detection capabilities: the model obtained an mAP@0.5 of approximately 0.90 and an mAP@0.5:0.95 close to 0.80. These results confirm the robustness of the network across various intersection-over-union thresholds.

Overall, the analysis demonstrates that the YOLOv5-based model trained with the Roboflow dataset achieved stable convergence, high detection accuracy, and generalization capacity suitable for real-world agricultural environments. The combination of effective data augmentation, adaptive optimization, and transfer learning contributed to the high performance achieved. Consequently, this model represents a significant step toward the implementation of intelligent robotic systems capable of early and accurate identification of plant diseases in tomato crops.

5.2. Motion Analysis Results

For the motion analysis, a study of parameters was carried out at two different stages. The first motion study was conducted with the prismatic actuators not extended in order to obtain data on the energy consumption and torque of each rotary motor. These parameters are common regardless of the status of the prismatic actuators. In the second study, the same parameters were analyzed, but with the prismatic actuators extended, now including the linear speed and force of the prismatic actuators. For this, each motor was simulated with oscillating movement at a frequency of 1 hertz over a period of two seconds, applying the effect of gravity. Finally, statistical tests of normality and comparison of means were performed to understand whether the use of prismatic joints has an effect on the motors.

In

Figure 14, the five motors share rotations when performing the simulation. Motors 1 and 2 show some differences in the amplitude of their movement, suggesting an increase in torque when the joints are extended. Motors 3, 4, and 5 are located after prismatic joints, so the effects on torque are negligible, as shown in graphs c, d, and e. Subsequently, a normality test was performed for the data from motors 1 and 2. The normality analysis of the torque distributions was carried out using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. The results indicated that the torque data for Motors 1, 2, 1E, and 2E followed a normal distribution, with

p-values above

(

Motor 1:

;

Motor 2:

;

Motor 1E:

;

Motor 2E:

). Therefore, these datasets can be treated under the assumption of normality. In contrast, the remaining motors presented

p-values below

, indicating non-normal behavior in their torque profiles.

A paired

t-test was conducted to compare the torque values between the non-extended and extended configurations, as shown in

Table 3. No statistically significant differences were found for either pair (

). The mean differences were zero and the 95% confidence intervals included zero, indicating no systematic bias. However, Motor 2 exhibited a much larger standard deviation (SD = 48.00) compared to Motor 1 (SD = 2.66), suggesting greater variability in dynamic response despite similar mean performance.

In

Figure 15, the energy consumption of the five actuated joints is presented for both prismatic configurations (extended and unextended). The results reveal that Motors 1 and 2 exhibit the highest energy demands due to their location at the base and the increased mechanical load during arm extension. The difference between configurations suggests that the prismatic extension introduces additional power requirements in the proximal joints, mainly during acceleration phases. Conversely, Motors 3, 4, and 5 maintain nearly identical consumption patterns, indicating that distal actuators operate with minimal variation regardless of prismatic extension. This behavior confirms the mechanical efficiency and balanced distribution of energy throughout the manipulator’s structure.

Given the non-normal distribution of the differences, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed as a non-parametric alternative. The results revealed statistically significant differences for both torque pairs (

,

, and

), indicating that the extended configuration produced systematically different torque distributions compared with the non-extended setup, as shown in

Table 4.

In

Figure 16, the force and displacement profiles of the prismatic joints are presented during the simulation sequence.

Figure 16a corresponds to the first prismatic actuator, which reaches a peak displacement of approximately 20 at mid-cycle while maintaining a nearly constant applied force of 23 N.

Figure 16b illustrates the behavior of the second prismatic joint, showing a similar triangular displacement pattern but with a higher constant force of 50 N. These profiles indicate that both actuators perform controlled linear extensions to modulate the robot’s reach during operation.

When compared with the torque simulations of the five rotational joints, these results confirm that the prismatic actuators contribute minimally to overall torque variation but are essential for positional stability and workspace adaptability. The synchronization between the rotational and prismatic joints ensures smooth end-effector trajectories, balancing energy distribution and mechanical effort throughout the manipulator. Furthermore, the mechanical validation through a finite element analysis using an adaptive h-mesh method with three iterations confirmed structural stability under simulated loading conditions, demonstrating that the applied forces remained within the allowable limits of the selected materials.

5.3. Systems Integration

A dedicated control panel was developed to centralize all electrical and communication components required for the robot’s operation. This panel houses the Siemens PLC controllers, power supplies, drivers, and protection modules, ensuring effective control of the manipulator and enabling the execution of monitoring routines, as shown in

Figure 17. Through this interface, the end-effector performs precise movements and captures the necessary images for disease analysis using the integrated neural network.

Once each subsystem—mechanical, electronic, and computational—had been independently tested, all components were integrated into a unified platform. The integration phase involved validating interconnections, communication protocols, and real-time data transfer between the PLCs, Raspberry Pi 4, and the robotic arm’s motion control modules. The complete system was then assembled and tested to verify coordinated operation of all components within a single functional framework.

Real-Time Detection

Figure 18 presents a demonstration of the real-time detection capabilities of the neural network developed for diagnosing tomato plant diseases. Two representative sets of images are displayed:

Figure 18a shows tomato plants affected by Yellow Leaf Curl, while

Figure 18b illustrates plants suffering from Leaf Mold. This visual evidence highlights the effectiveness and accuracy of the neural network in distinguishing between different tomato plant diseases.

In

Figure 18a, the characteristic symptoms of Yellow Leaf Curl are clearly detected. The network successfully identifies the distinct visual cues associated with this disease, enabling real-time recognition under natural lighting conditions.

Figure 18b displays the identification of Leaf Mold, where the neural network effectively captures the specific patterns and color variations indicative of fungal infection. These results confirm the robustness of the proposed detection model in differentiating visually similar pathologies.

The real-time detection results exemplify the practical application of the neural network in precision agriculture. By enabling fast and accurate disease identification, the proposed system empowers farmers with timely diagnostic information, supporting proactive measures to minimize crop loss. The integration of artificial intelligence in agricultural practices thus constitutes a key advancement toward sustainable and efficient farming methodologies.

Figure 19 illustrates the robotic system operating in a simulated agricultural environment, demonstrating its capacity for the real-time monitoring of tomato plants. The integration allows seamless coordination among perception, processing, and actuation modules, resulting in a fully autonomous monitoring cycle.

Figure 20 shows the successful integration of the robotic arm with its custom-designed end-effector, which incorporates a high-resolution camera module for real-time visual detection. The captured images are processed locally on the Raspberry Pi 4 using the YOLOv5 model, enabling on-site detection of diseases such as Yellow Leaf Curl with high precision. The synchronized operation between the manipulator’s motion control, the vision system, and the neural network highlights the robot’s capability to autonomously identify plant health conditions without human intervention.

This integration represents the culmination of a multidisciplinary approach combining mechatronics, artificial intelligence, and precision agriculture. The system’s design allows continuous plant monitoring, early disease identification, and data collection for predictive analysis. As demonstrated in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20, the developed robotic platform provides an effective technological solution for improving crop management, optimizing resource use, and enhancing overall agricultural productivity through real-time automation.

6. Discussion

The integration of robotics and artificial intelligence continues to redefine agricultural automation by improving precision, adaptability, and sustainability. The proposed system combines a 7-DOF redundant manipulator (5R + 2P) with a YOLOv5-based neural network for real-time tomato plant disease detection. This configuration expands the operational workspace and enhances flexibility, surpassing traditional fixed or linear monitoring systems. Roshanianfard and Noguchi [

37] designed a 5-DOF arm for heavy crop harvesting. This project, at the simulation level, reported optimal performance. However, no prior work has reported a 7-DOF robotic configuration (5R + 2P) for continuous plant monitoring, positioning this study as a novel contribution to agricultural robotics.

Regarding visual processing, YOLOv5 demonstrates an effective balance between accuracy, speed, and efficiency for embedded systems. Compared with earlier YOLOv3 and YOLOv4 architectures [

38], YOLOv5 introduces improved anchor optimization and data augmentation, making it suitable for low-power hardware such as the Raspberry Pi 4. Although newer models such as YOLOv8 [

39] achieve slightly higher accuracy, they demand significantly greater computational resources, which limits their field applicability. Studies comparing both architectures in agricultural contexts confirm that YOLOv5 provides higher energy efficiency and real-time inference performance (8–9 FPS), making it ideal for mobile robotic deployment.

The redundancy and adaptability of the robotic platform align with the design principles demonstrated by Syed et al. [

40], who highlighted the benefits of redundant manipulators for dexterity and safety, and by Kamarianakis et al. [

41], who developed low-cost robotic camera systems for greenhouse applications. Similarly, Andriyanov [

42] and Islam et al. [

43] validated the integration of computer vision and manipulation intelligence in crop management, reinforcing the viability of coupling deep learning with mechanical adaptability.

Finally, the modular and scalable nature of the proposed system follows the technological direction outlined by Mahmud et al. [

44], emphasizing that modern agricultural platforms must be data-driven, reconfigurable, and capable of multi-crop adaptation. Consequently, the presented 7-DOF architecture with YOLOv5 represents a practical and efficient solution for real-time crop monitoring, capable of extending its application to diverse agricultural environments through retraining and structural reconfiguration.

7. Conclusions

This study successfully developed and implemented a neural network-based system for the detection of diseases in tomato plant leaves, integrated into a custom 7-degree-of-freedom robotic manipulator. The model, built on the YOLOv5 architecture, demonstrated high precision in identifying various tomato leaf diseases, achieving up to 99% accuracy in specific classes such as Spider Mites and Leaf Mold. The dataset, composed of 7864 annotated images, proved robust and diverse, allowing the model to generalize effectively under real-world conditions.

The proposed robotic system, featuring two prismatic joints and an intelligent end-effector, enables flexible monitoring of plants at different growth stages, ensuring adaptability and precision in inspection tasks. The combination of advanced vision-based neural network detection and robotic manipulation presents a valuable contribution to precision agriculture.

Although the proposed system demonstrated promising results in terms of detection accuracy and operational performance, the experimental validation remains limited. The physical tests conducted so far were restricted to a controlled environment and a specific tomato crop dataset. Therefore, further experimentation is required to evaluate the system’s robustness under diverse agricultural conditions and across different plant species. Future work will include extended field trials and the incorporation of additional crops, allowing the neural network to adapt to varying leaf morphologies, lighting conditions, and disease types. These efforts will contribute to consolidating the model’s reliability and its applicability to broader agricultural contexts.