Study on Optimal Operation of Heat Pump Drying System Throughout the Entire Drying Process Based on the Material Drying Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

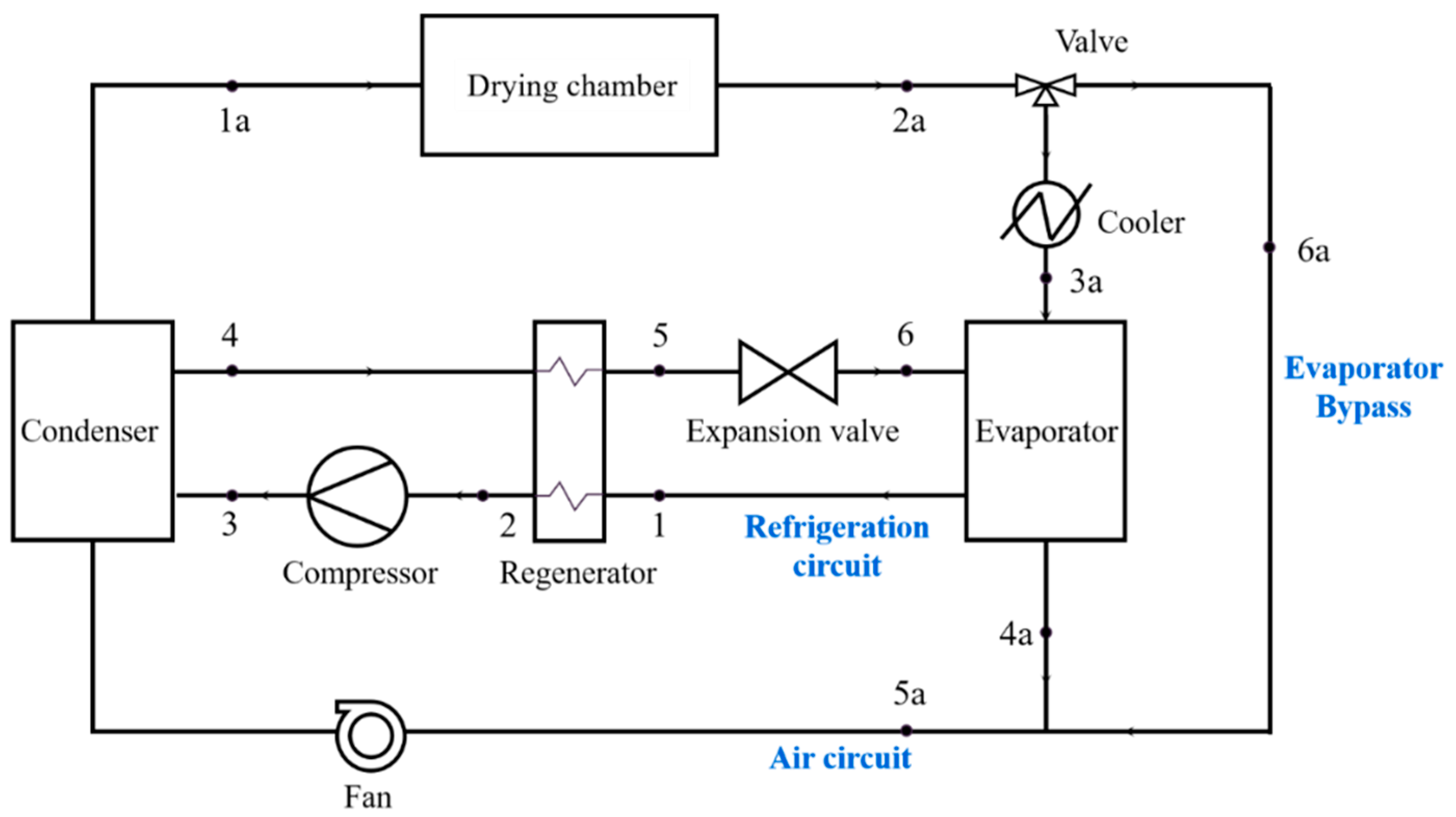

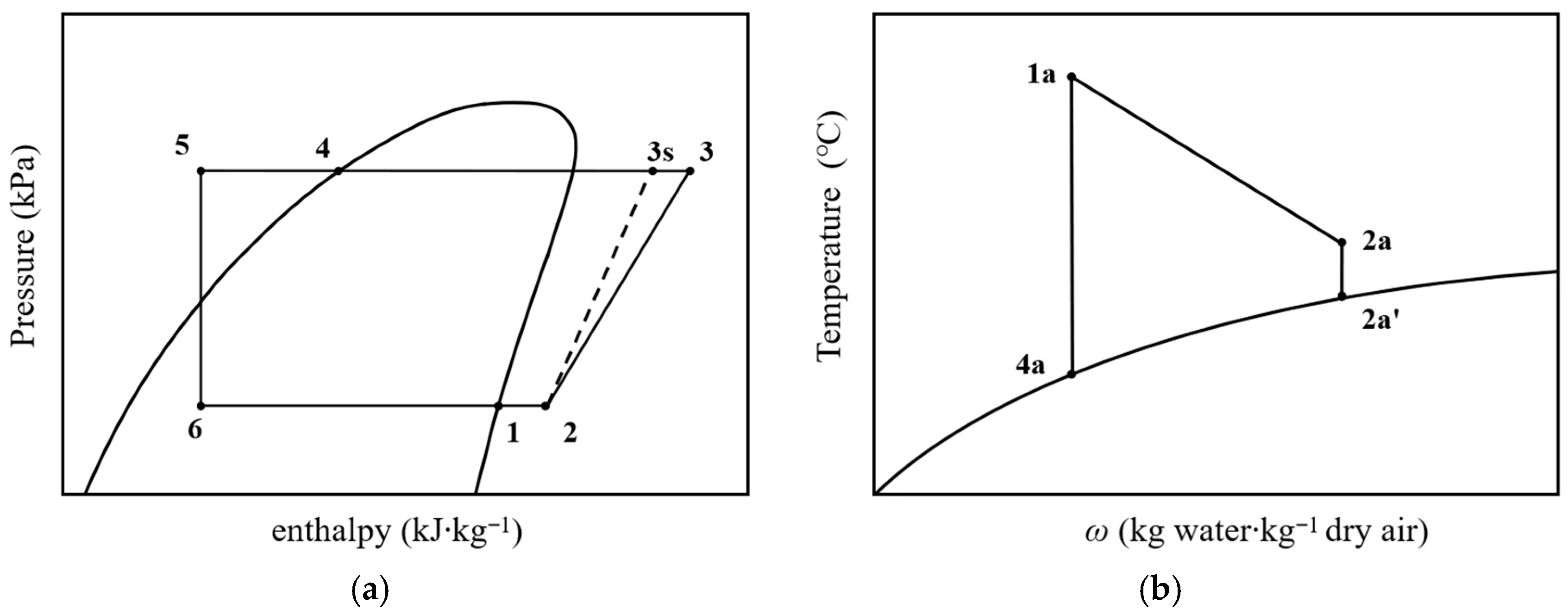

2. Problem Statements

3. Mathematical Model

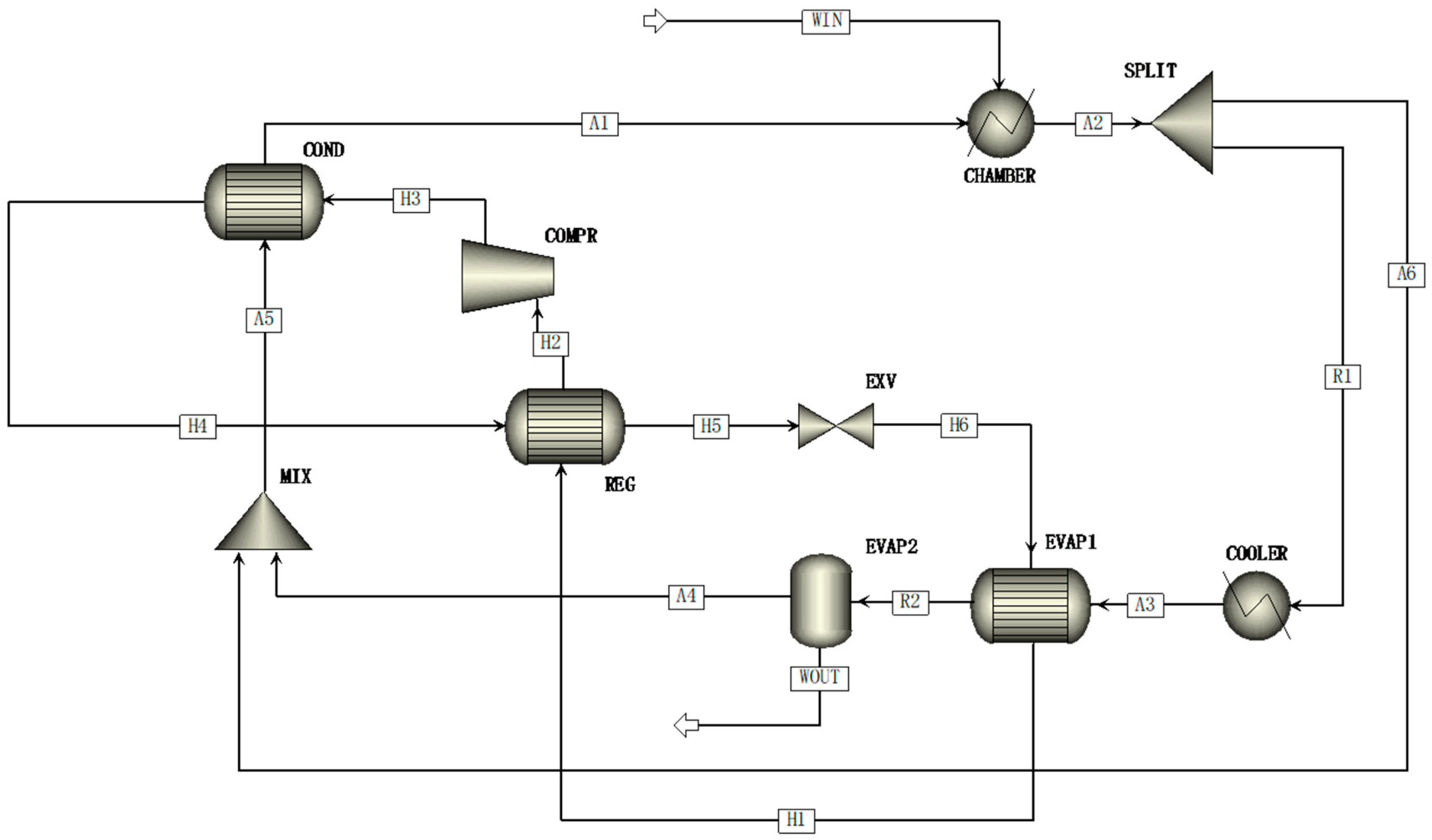

3.1. Numerical Simulation

- 1.

- All unit modules of the heat pump system operate under steady-state conditions [26];

- 2.

- Pressure drops in heat exchangers and heat losses in the drying chamber are neglected [27];

- 3.

- Working fluid leaving the evaporator and condenser is saturated vapor and saturated liquid, respectively [28];

- 4.

- The isentropic efficiency of the compressor is assumed to be 75% [29].

3.2. Evaluation Criterion

4. Case Study

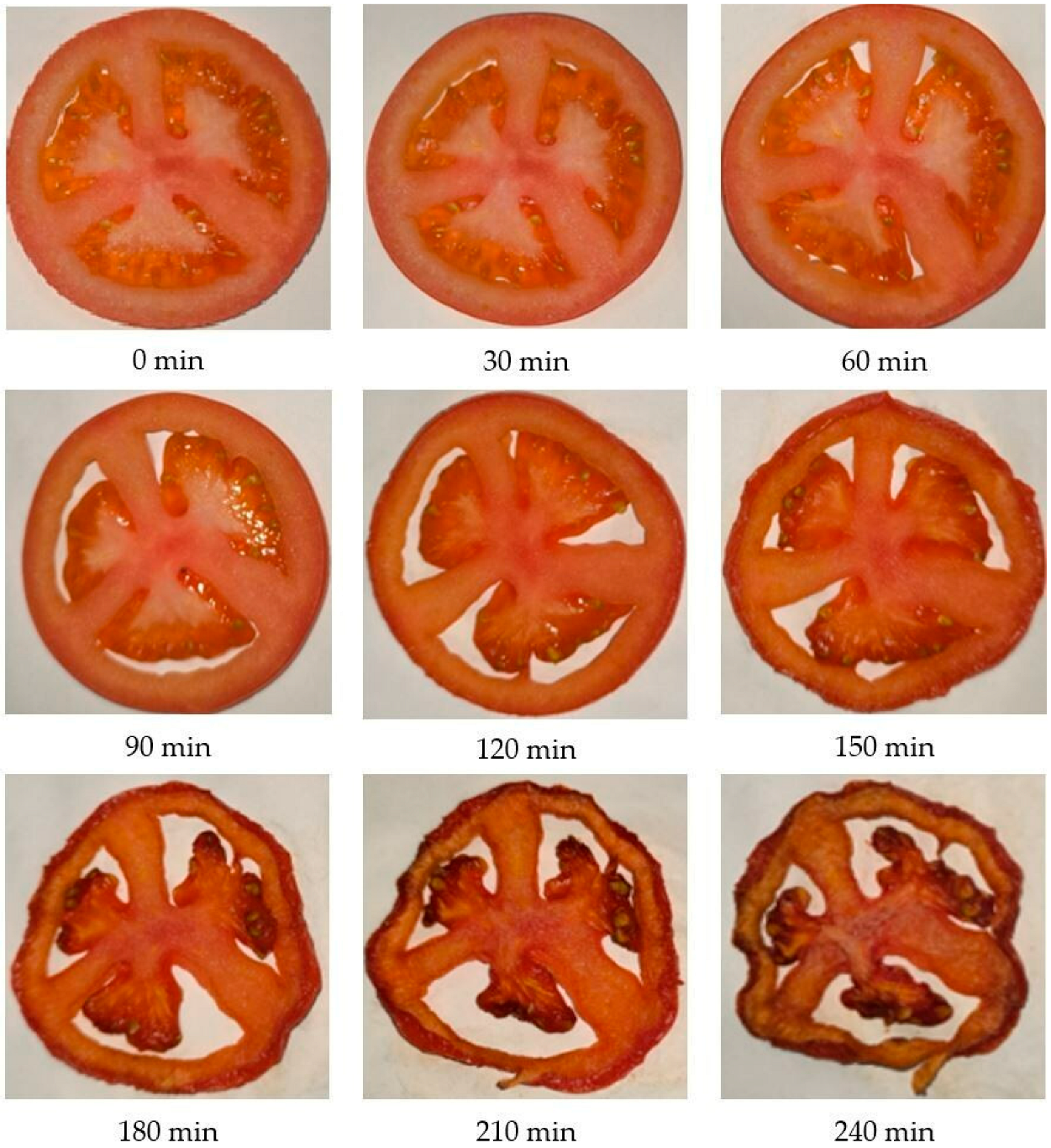

4.1. Tomato Drying Experiments

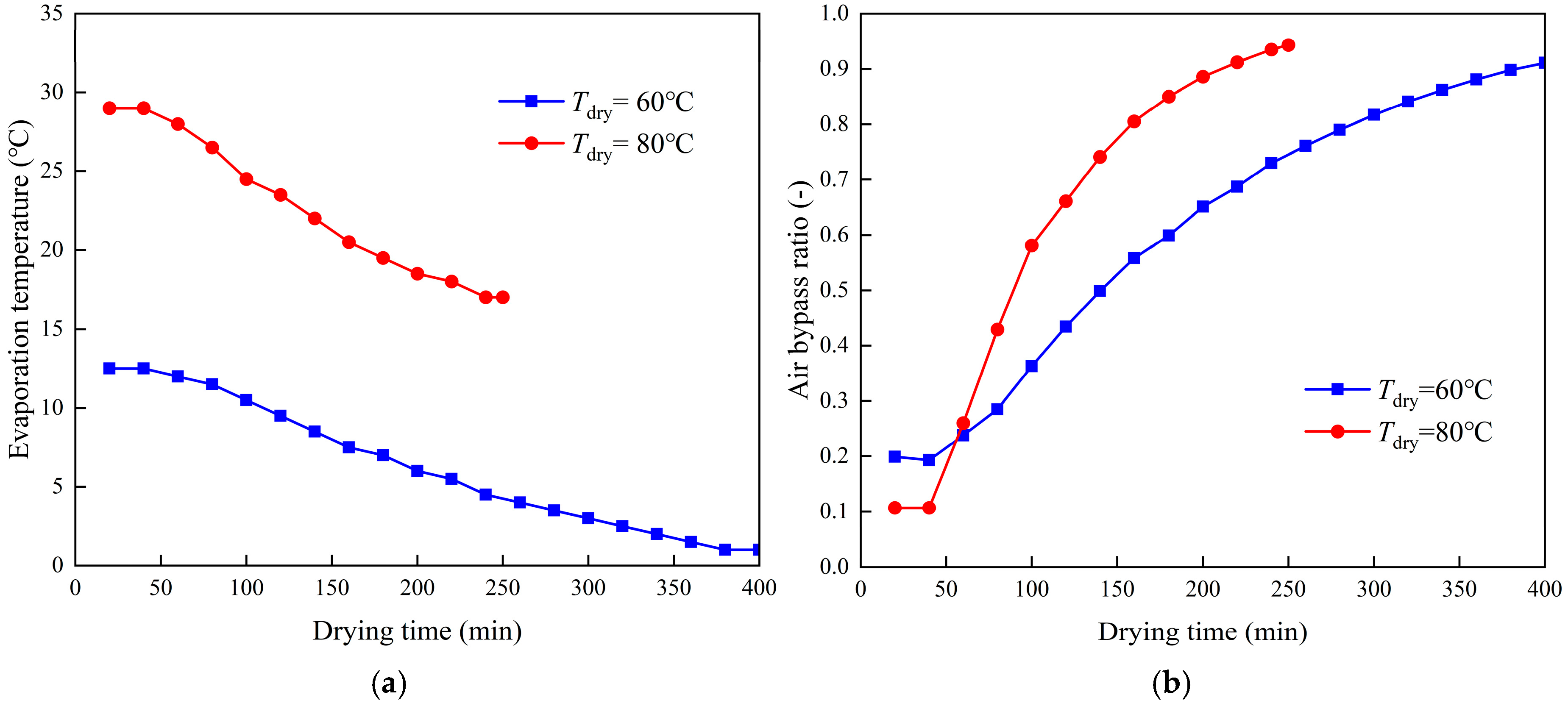

4.2. Optimized Operation of HPD System Under Variable Operating Conditions

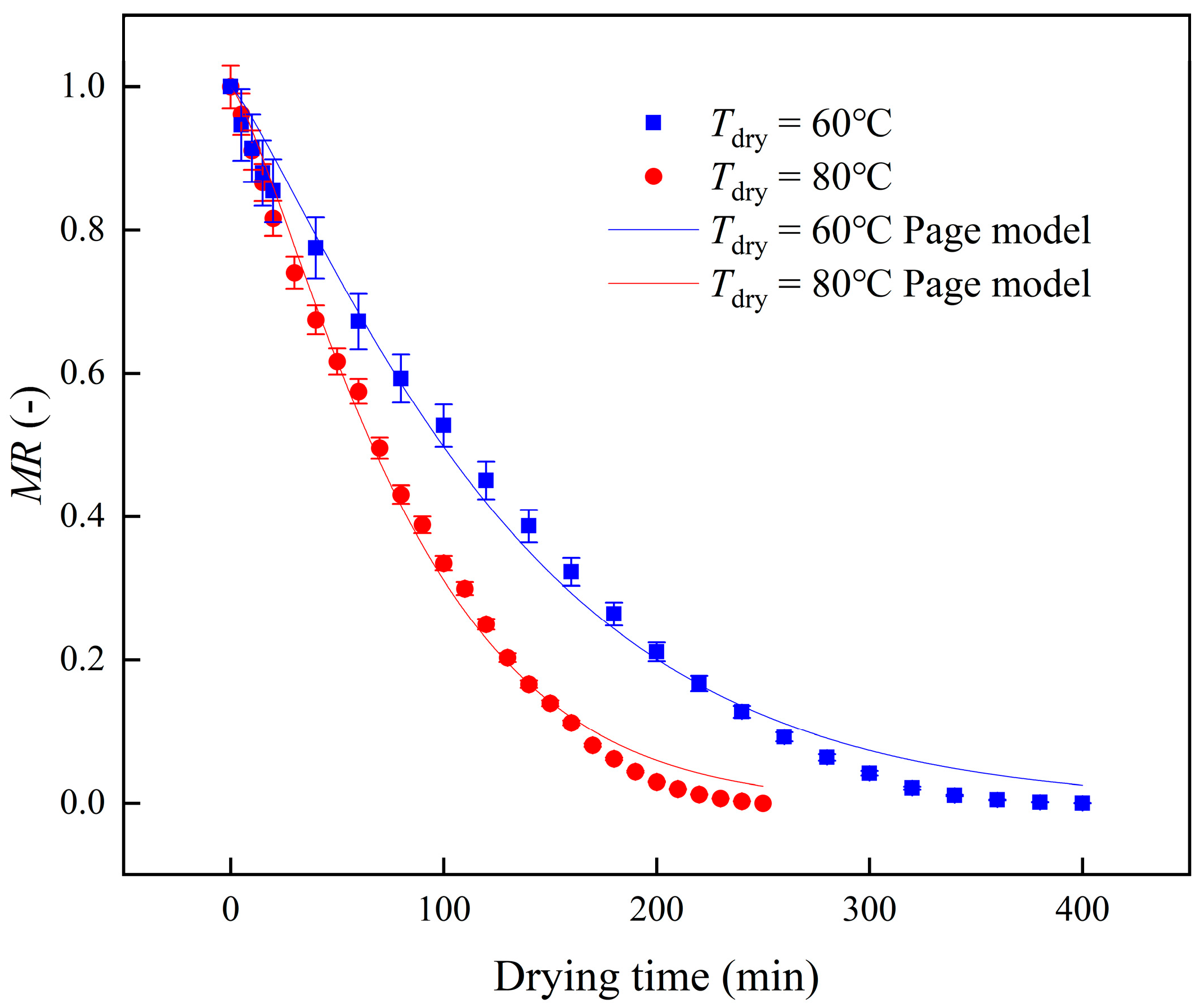

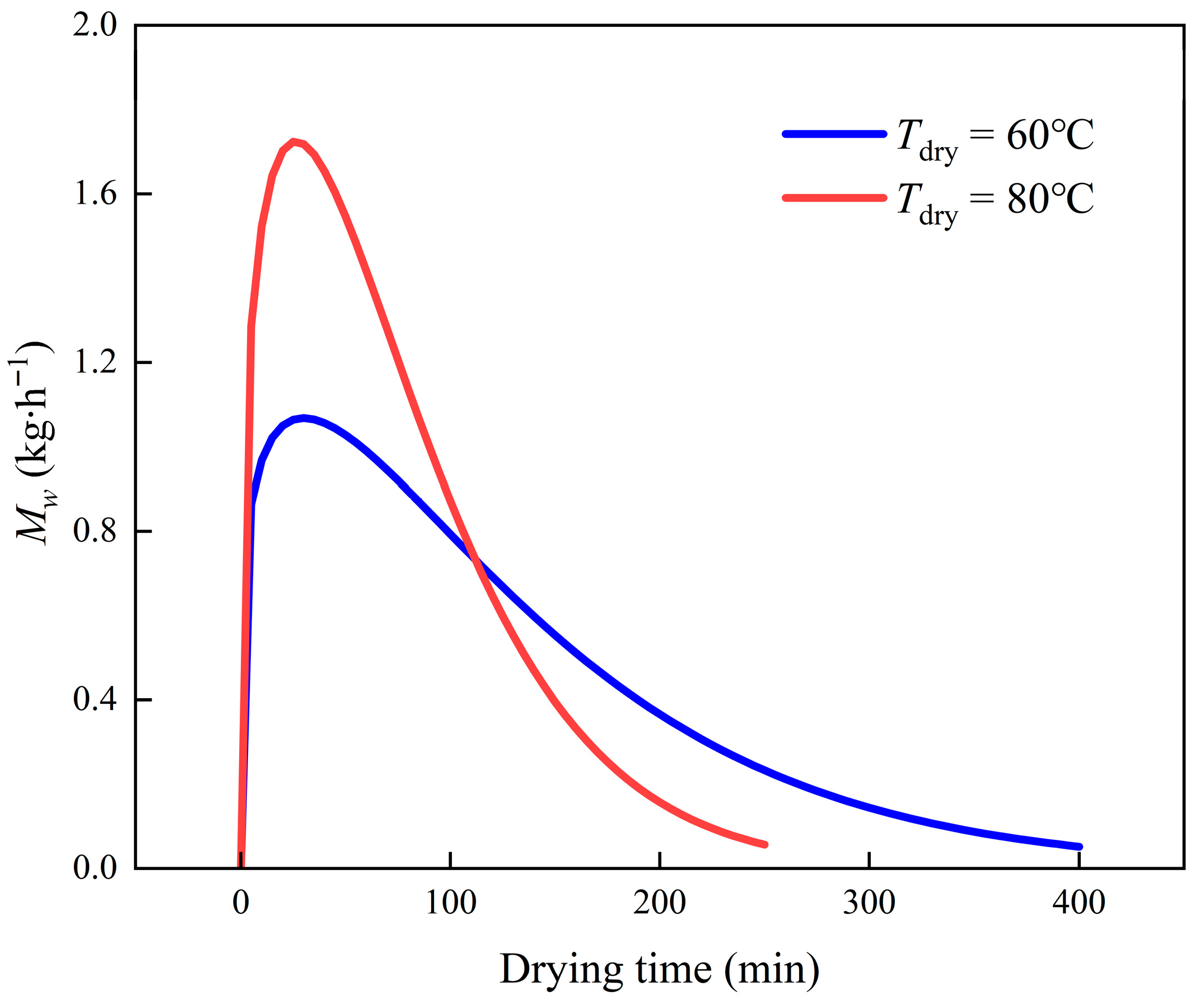

4.2.1. Drying Characteristic Curves of Material Samples

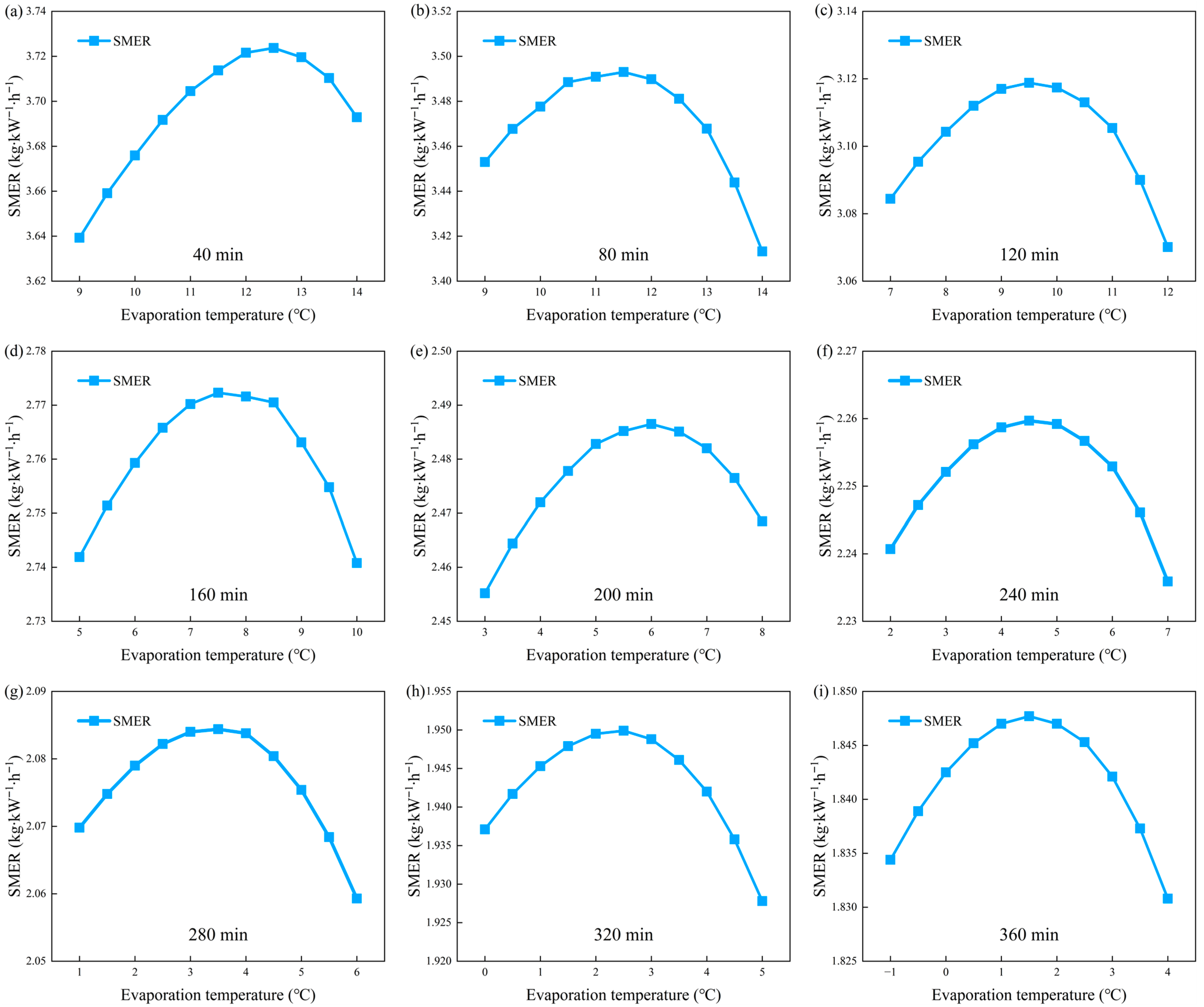

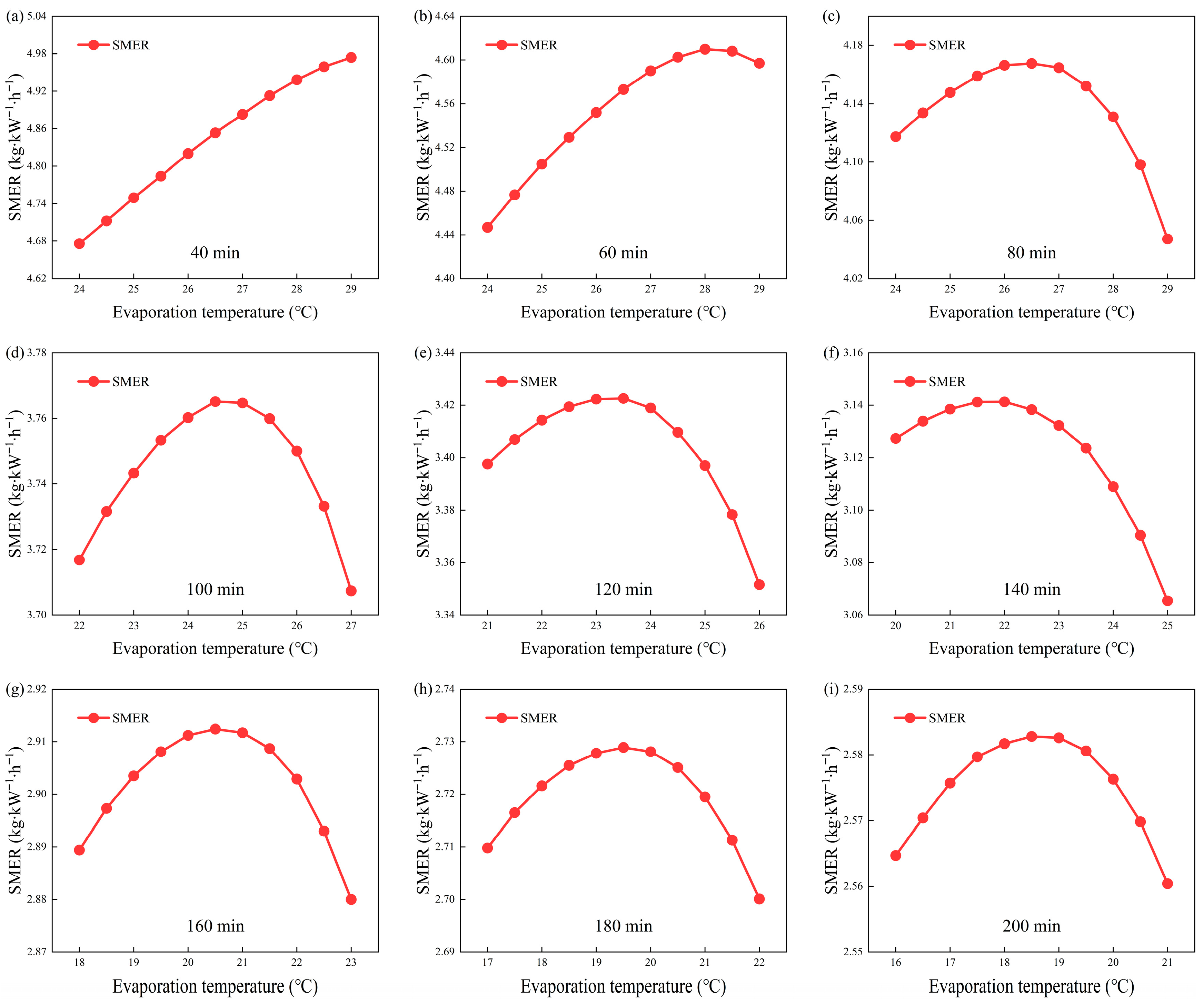

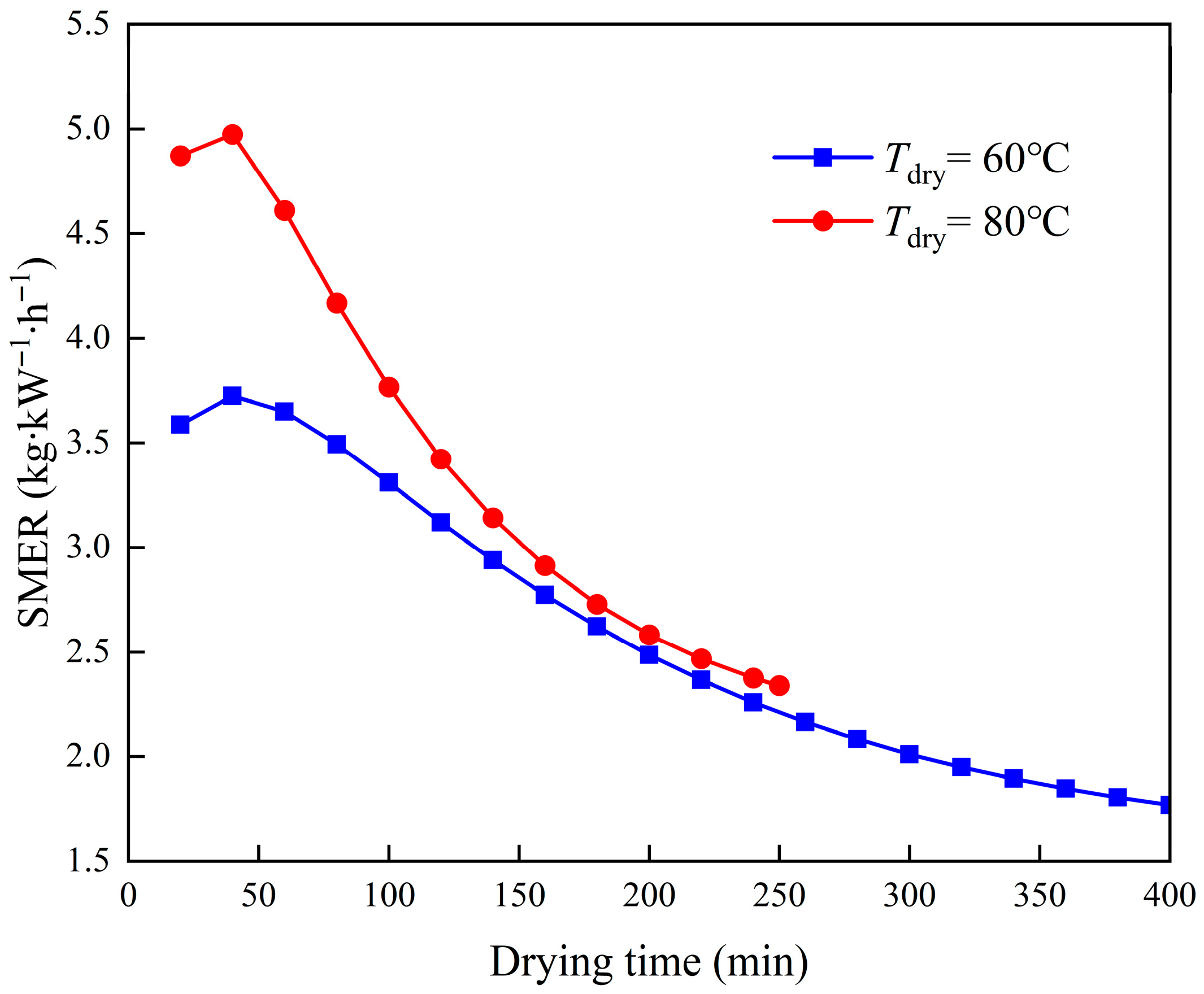

4.2.2. System Simulation and Optimization of Operating Parameters

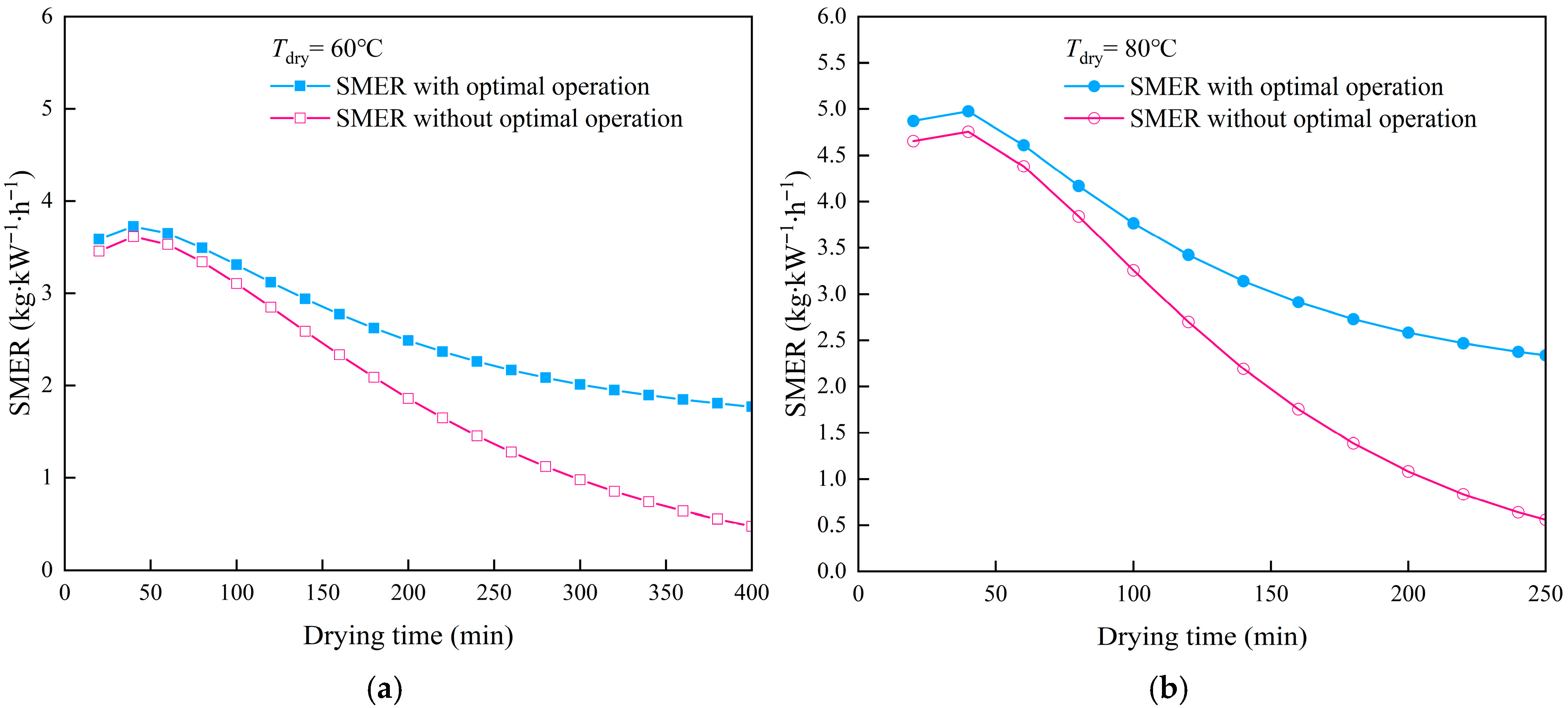

4.2.3. Analysis of Energy-Saving Effects of Optimized Operation

5. Conclusions

- Necessity of optimized operation: In practical applications, the HPD system often operates inefficiently due to the lack of dynamic control strategies. Dynamic control of the optimal evaporation temperature can significantly improve system performance, particularly in the later drying stages. Optimized operation effectively prevents a substantial decrease in SMER.

- Optimal operation strategy: Based on a case study, an optimal operation strategy for the entire drying process of the HPD system, tailored to the material’s drying characteristics, is proposed. During drying, the system should dynamically adjust the evaporation temperature and air bypass ratio in response to changes in the material’s drying rate. The simulated results show that optimal operation significantly improves the system’s SMER and reduces the total energy consumption during drying.

- Significant energy-saving effects: At drying temperatures of 60 °C and 80 °C, the HPD system with the optimized operating strategy reduced the total electrical consumption by 31.60% and 32.87%, respectively, compared to the constant evaporation temperature mode.

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achakulwisut, P.; Erickson, P.; Guivarch, C.; Schaeffer, R.; Brutschin, E.; Pye, S. Global Fossil Fuel Reduction Pathways Under Different Climate Mitigation Strategies and Ambitions. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouya, A. Performance assessment of a heat pump and a concentrated photovoltaic thermal system during the wood drying process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 180, 115923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluczek, A.; Olszewski, P. Energy audits in industrial processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3437–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Min, R.; Zhou, K.; Traffano-Schiffo, M.V.; Dong, Q.; Luo, W. Effects of vacuum drying assisted with condensation on drying characteristics and quality of apple slices. J. Food Eng. 2023, 340, 111286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibo, Z.; Kun, W. Annual performance analysis of heat pump drying system with waste heat recovery. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, L.J.; Othman, M.Y.; Mat, S.; Ruslan, H.; Sopian, K. Review of heat pump systems for drying application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4788–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Fix, A.; Seabourne, T.; Li, Y.; Li, G. A comprehensive review of heat pump wood drying technologies. Energy 2024, 311, 133241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjehsarabi, H.; Dincer, I.; Gungor, A. Exergoeconomic analysis of a heat pump tumbler dryer. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Cui, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Yu, Z. Drying characteristics of banana slices under heat pump-electrohydrodynamic (EHD) combined drying. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 54, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatanović, I.; Komatina, M.; Antonijević, D. Experimental investigation of the efficiency of heat pump drying system with full air recirculation. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Wu, W.; Huang, H.; Jin, Y.; Gao, P. Experimental investigation of the effect of heat pump drying temperature on drying characteristics of Auricularia auricula. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 71, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sarkar, J.; Sahoo, R.R. Experimental energy-exergy performance and kinetics analyses of compact dual-mode heat pump drying of food chips. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Huo, Z.; Ding, C. Experimental study on thermal performance of a closed heat pump drying system. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 51, 103590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Icier, F. Optimization of drying of olive leaves in a pilot-scale heat pump dryer. Dry. Technol. 2009, 27, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, Z.; Hepbasli, A. Application of conventional and advanced exergy analyses to evaluate the performance of a ground-source heat pump (GSHP) dryer used in food drying. Energy Convers. Manage. 2014, 78, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Guo, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y. Design and experimental study of an air source heat pump for drying with dual modes of single stage and cascade cycle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 129, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengchun, L.; Xueqiang, L.; Mengjie, S.; Hailong, L.; Zhili, S. Experimental investigation on drying performance of an existed enclosed fixed frequency air source heat pump drying system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 130, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.H.; Yu, W.; Cao, X.; Shao, L.L.; Zhang, C.L. Evaluation of heat pump dryers from the perspective of energy efficiency and operational robustness. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 118995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abano, E.E.; Ma, H.; Qu, W. Influence of air temperature on the drying kinetics and quality of tomato slices. J. Food Process. Technol. 2011, 2, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, L.; Adebisi, S.A.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Adetoro, R.O.; Tijani, K.O. Bioactive compounds’ contents, drying kinetics and mathematical modelling of tomato slices influenced by drying temperatures and time. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadin, R.; Chegini, G.R.; Sadin, H. The effect of temperature and slice thickness on drying kinetics tomato in the infrared dryer. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 50, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, A.; Stojceska, V.; Tassou, S.A. A systematic review on the recent advances of the energy efficiency improvements in non-conventional food drying technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Yu, X. Effect of compressor speeds on performance of a closed loop heat pump drying system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Fan, S. Performance analysis of hydrate-based refrigeration system. Energy Convers. Manage. 2017, 146, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ding, G.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Shu, S.M.; Tan, J.Y. Experimental Investigation and Numerical Simulation for High Temperature Air Source Heat Pump with New Mixed-Refrigerant. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 541, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Deng, W.; Wang, L.; Hu, M.; Chen, G.; Su, Y. Study on waste heat recovery from sludge drying exhaust gas based on High-Temperature heat pump coupled with steam compression. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 266, 125716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, U.S.; Khan, M.K. Calculation steps for the design of different components of heat pump dryers under constant drying rate condition. Dry. Technol. 2008, 26, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Feng, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y. Energy and economic performance comparison of heat pump and power cycle in low grade waste heat recovery. Energy 2022, 260, 125149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluleye, G.; Smith, R.; Jobson, M. Modelling and screening heat pump options for the exploitation of low grade waste heat in process sites. Appl. Energy 2016, 169, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galashov, N.N.; Gabdullina, A.I.; Kiselev, A.V.; Tsibulskiy, S.; Melnikov, D. Research of efficiency of the organic Rankine cycle on a mathematical model. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 92, 01070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, N.; Hepbasli, A. A review of heat-pump drying (HPD): Part 2—Applications and performance assessments. Energy Convers. Manage. 2009, 50, 2187–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.J.; Rosentrater, K.A. Optimal Designs of Air Source Heat Pump Dryers in Agro-food Processing Industry. Food Eng. Rev. 2023, 15, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Feng, X.; Wang, Y. Performance comparison of different heat pumps in low-temperature waste heat recovery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Miao, Y.; Xiang, H.; Tan, W.; Li, W. Effects of air-impingement jet drying on drying kinetics and quality retention of tomato slices. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; ElGamal, R.; Dong, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, C. Coupling effect of lycopene degradation and heat/mass transfer during the drying process of tomato. Dry. Technol. 2024, 42, 2379–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Module |

|---|---|

| Condenser | HeatX |

| Evaporator | HeatX + Flash2 |

| Regenerator | HeatX |

| Expansion valve | Valve |

| Compressor | Compr |

| Drying chamber | Heater + FSplit |

| Mixer | MIXER |

| Cooler | Heater |

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Drying Temperature | 60 | °C |

| Drying Relative Humidity | 0.15 | % |

| Circulating Air Pressure | 101.3 | kPa |

| Circulating Air Flow Rate | 400 | kg ∙ h−1 |

| Drying Rate | 3.085 | kg ∙ h−1 |

| Condensation Temperature | 59.95 | °C |

| Compressor Pressure | 1679.75 | kPa |

| Compressor Isentropic Efficiency | 0.75 | - |

| Evaporation Temperature | 12 | °C |

| Air Bypass Ratio | 0.241 | - |

| Refrigerant Mass Flow Rate | 70.07 | kg ∙ h−1 |

| Drying Temperature | k | n | R2 | Sum of Squared Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 °C | 0.00278 | 1.20002 | 0.99290 | 9.4417 × 10−4 |

| 80 °C | 0.00333 | 1.27248 | 0.99465 | 6.3922 × 10−4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, J.; Zhang, P.; ElGamal, R.; ElMasry, G.; Kishk, S.; Peng, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, L. Study on Optimal Operation of Heat Pump Drying System Throughout the Entire Drying Process Based on the Material Drying Characteristics. Processes 2025, 13, 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123883

Song J, Zhang P, ElGamal R, ElMasry G, Kishk S, Peng J, Liu C, Wang L. Study on Optimal Operation of Heat Pump Drying System Throughout the Entire Drying Process Based on the Material Drying Characteristics. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123883

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Junlin, Peikun Zhang, Ramadan ElGamal, Gamal ElMasry, Sameh Kishk, Junfeng Peng, Chuanping Liu, and Li Wang. 2025. "Study on Optimal Operation of Heat Pump Drying System Throughout the Entire Drying Process Based on the Material Drying Characteristics" Processes 13, no. 12: 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123883

APA StyleSong, J., Zhang, P., ElGamal, R., ElMasry, G., Kishk, S., Peng, J., Liu, C., & Wang, L. (2025). Study on Optimal Operation of Heat Pump Drying System Throughout the Entire Drying Process Based on the Material Drying Characteristics. Processes, 13(12), 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123883