Process Design for Optimizing Small Particle Diameter Light Hydrocarbon Recovery from Tight Gas Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

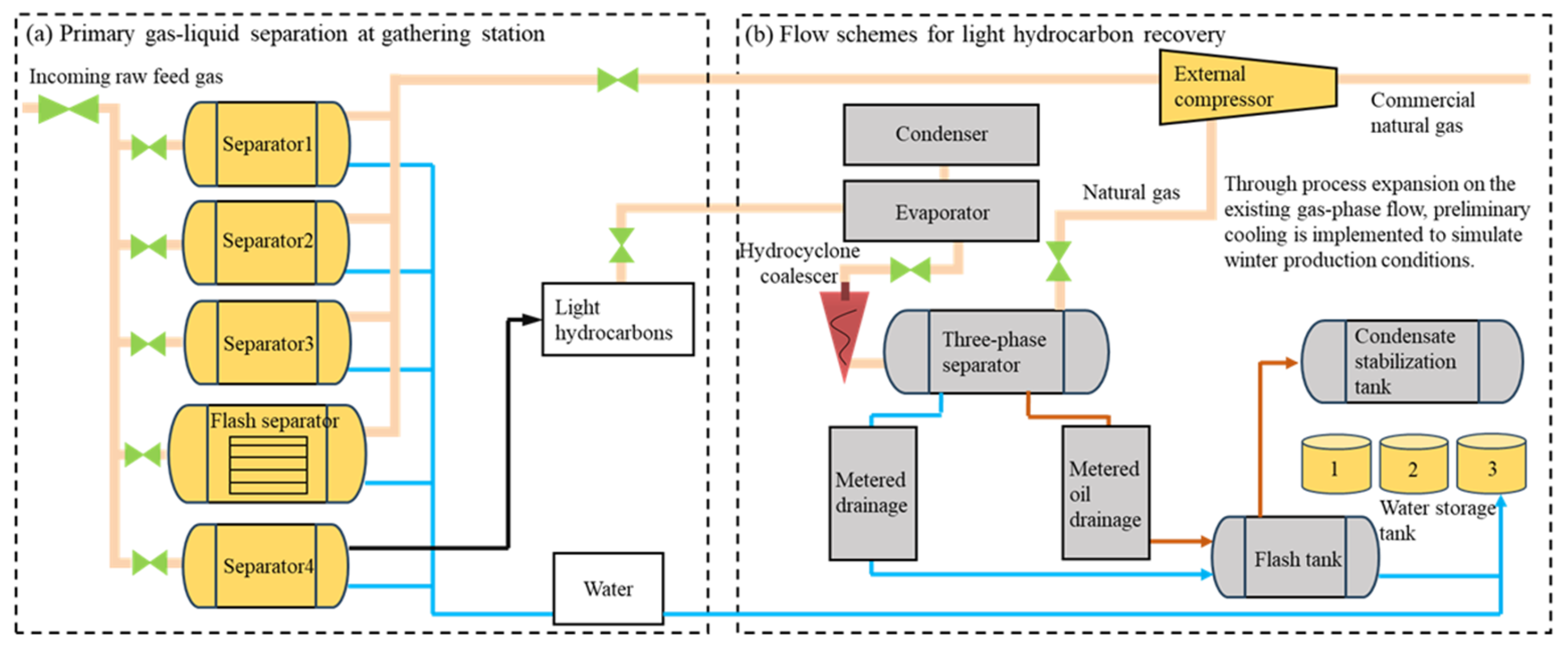

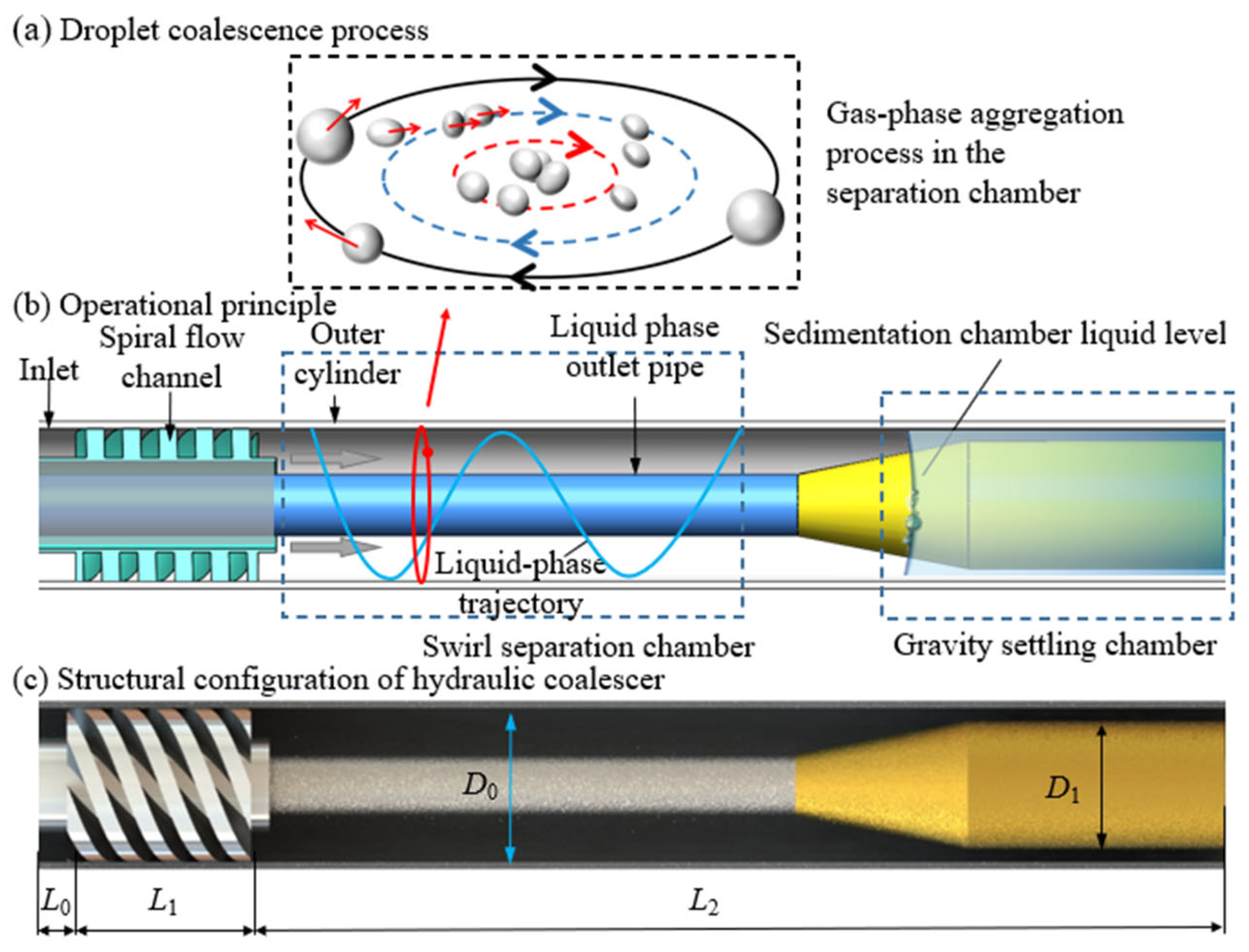

2. Design and Operating Principle

3. Methods

3.1. Response Surface Methodology

3.2. Numerical Simulation Method

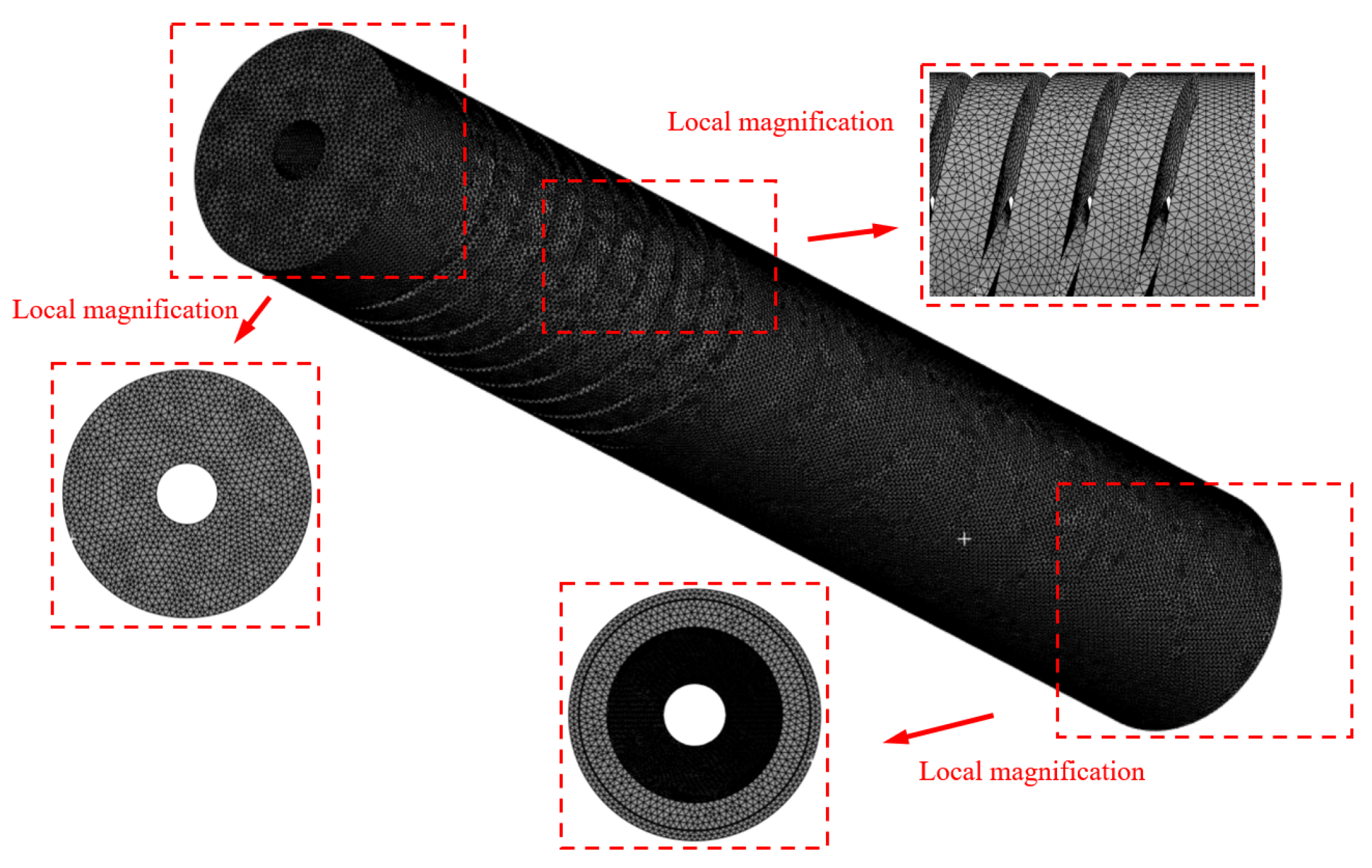

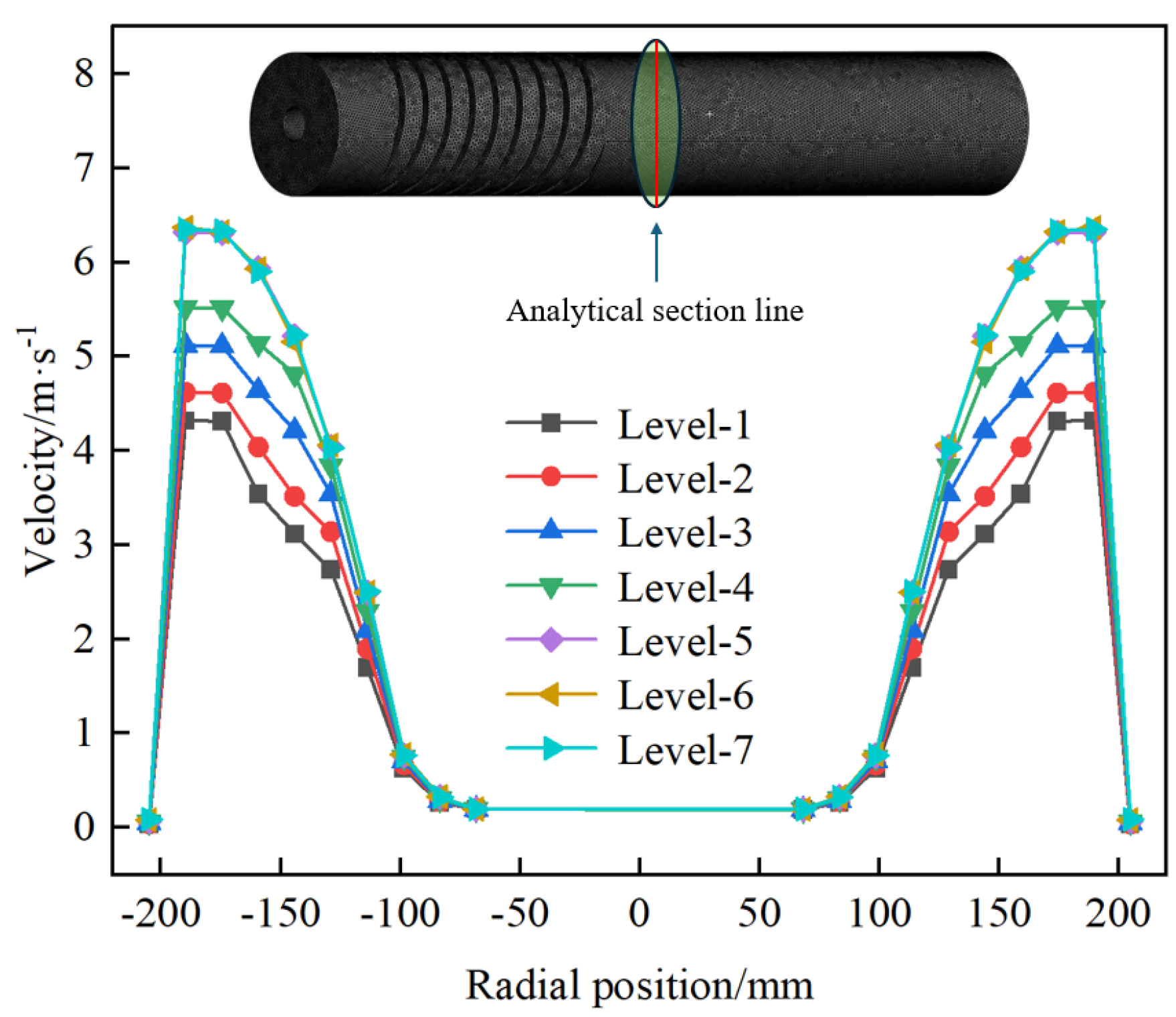

3.2.1. Fluid Domain and Mesh Generation

3.2.2. Numerical Model and Boundaries

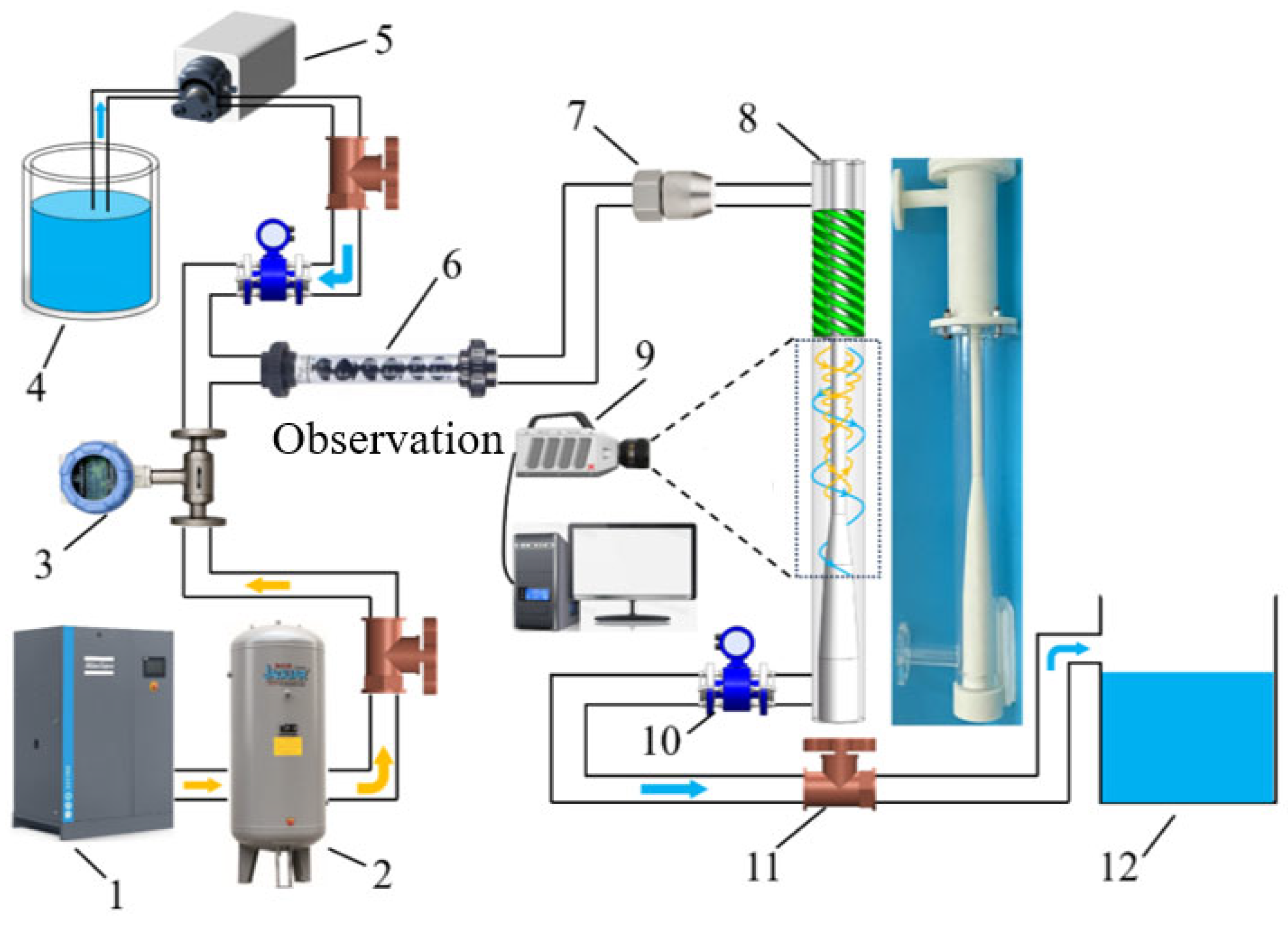

3.3. Experimental Methodology and Procedures

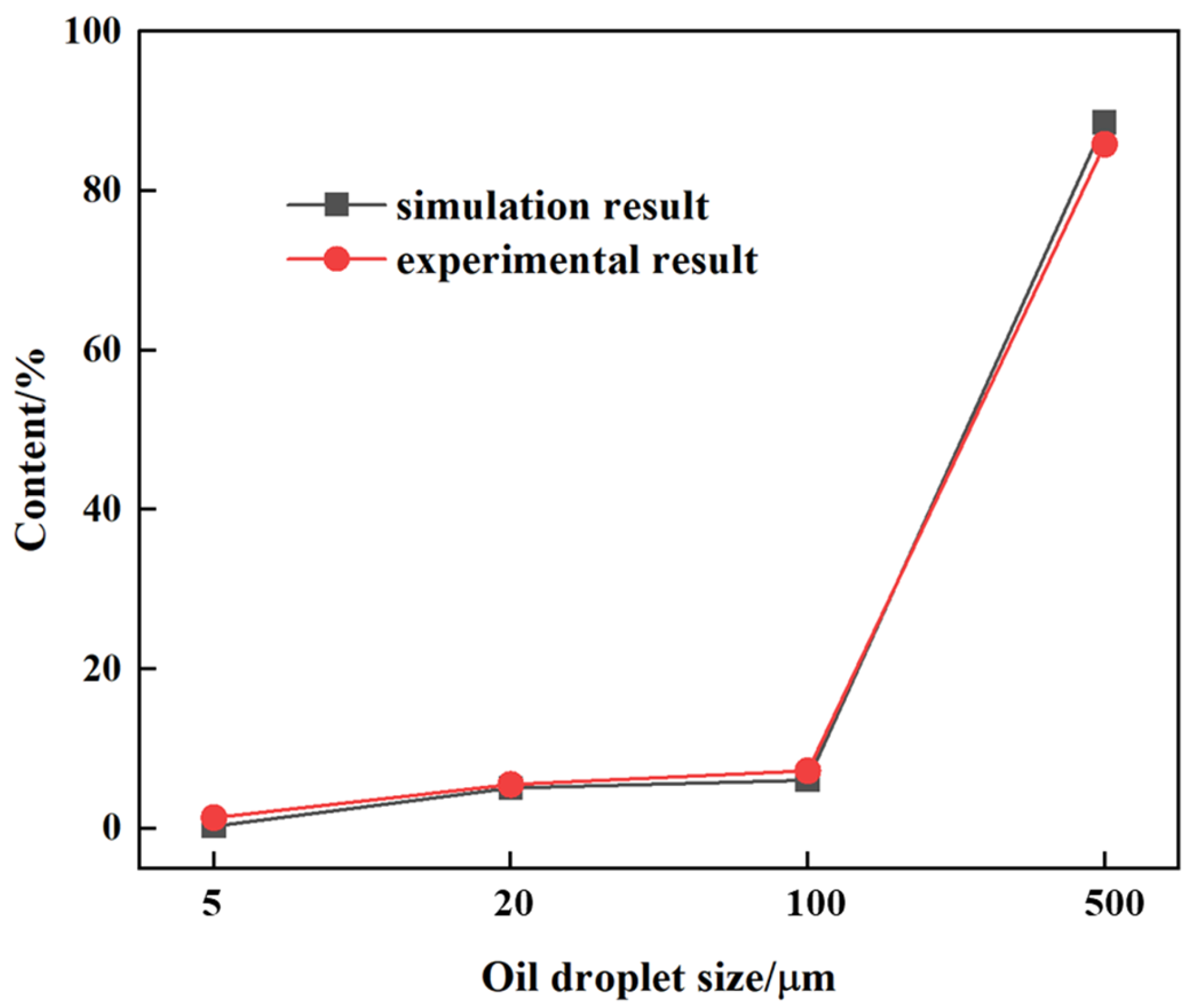

3.4. Comparison of Experimental and Simulation Results

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Box–Behnken Experimental Design

4.2. Results of Surface Optimization Response

4.3. Analysis of Variance of the Regression Model

4.4. Residual Analysis of the Regression Model

4.5. Experimental Validation of the Optimization Results

4.6. Numerical Validation of the Optimization Results

5. Conclusions

- (1)

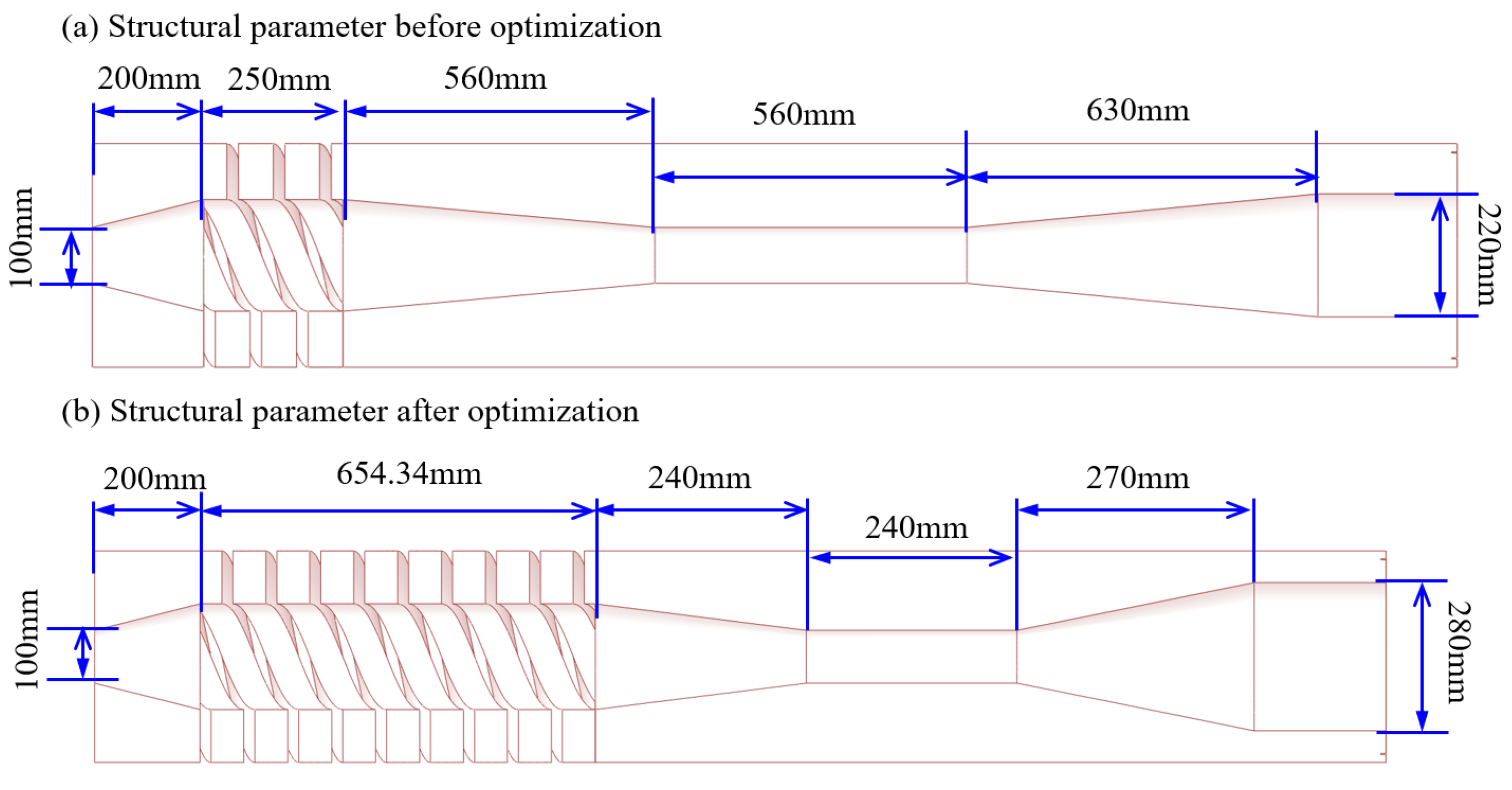

- Response surface methodology was adopted to optimize the structural parameters with higher significance, and a mathematical model relating structural parameters and coalescence efficiency was established. The optimal structural parameters of the hydraulic coalescer were obtained as follows: spiral flow channel length of 654.34 mm, cyclone cavity length of 750 mm, and bottom column outer diameter of 280 mm.

- (2)

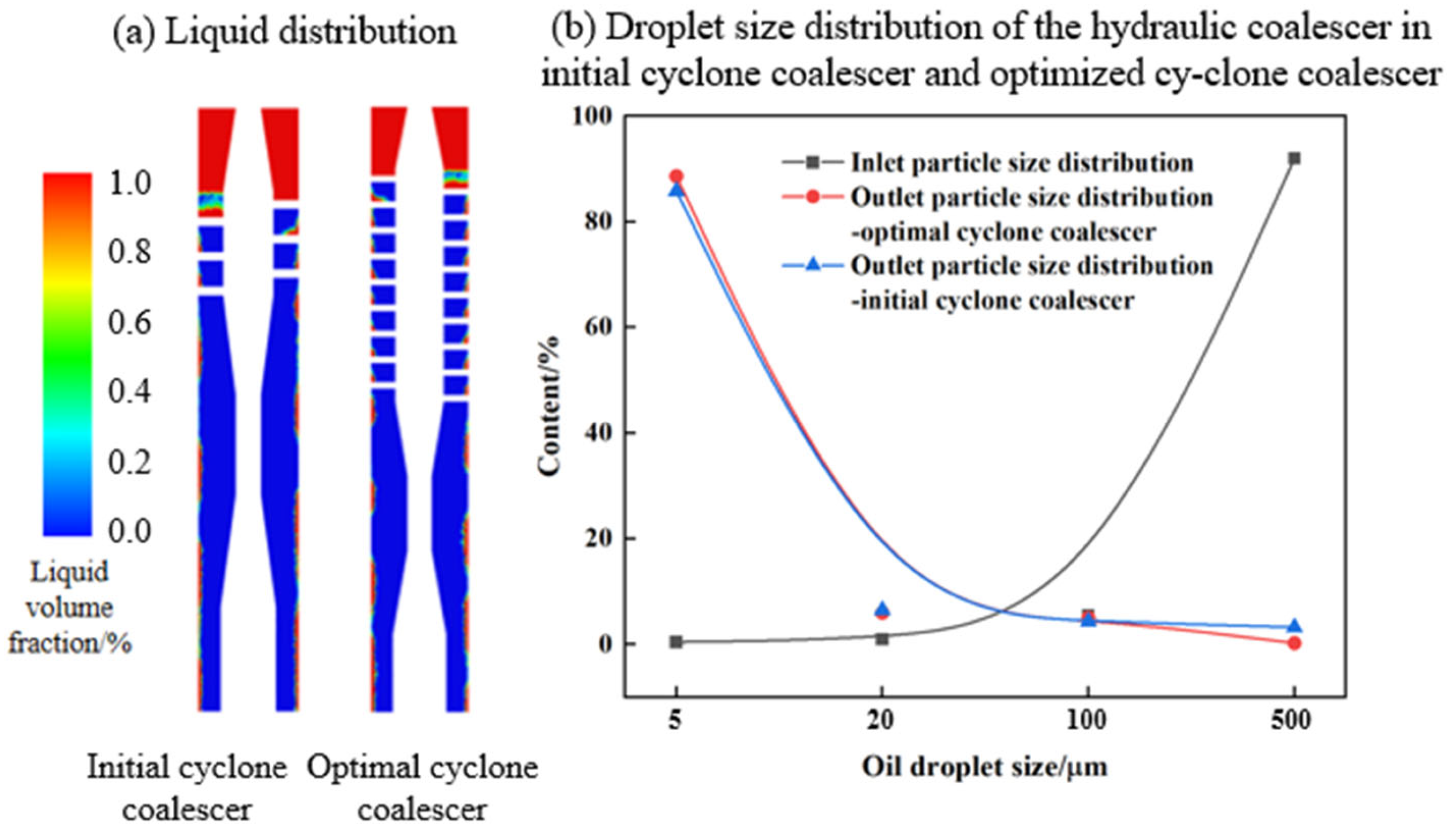

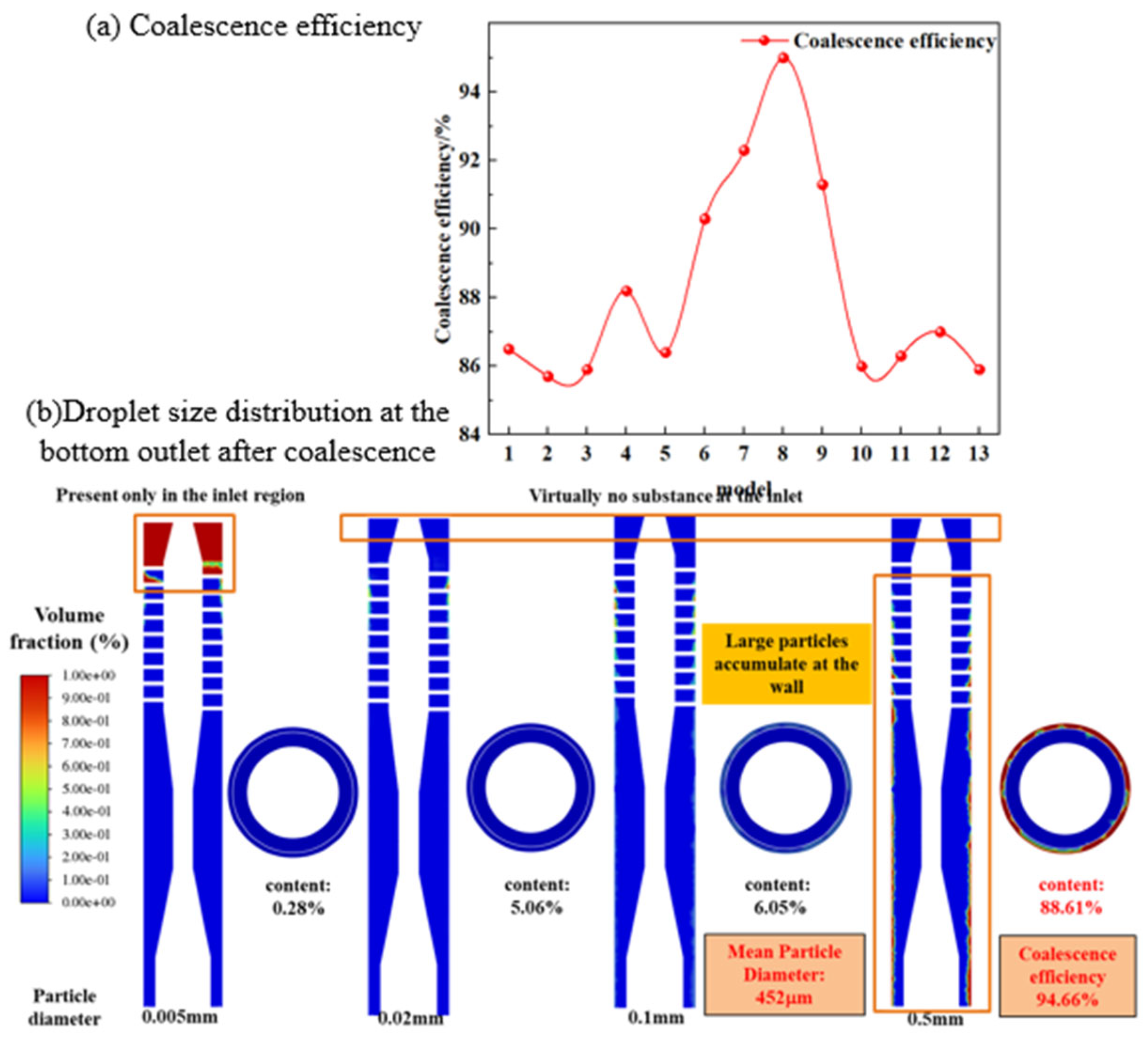

- Numerical simulation comparison studies showed that the liquid phase flow area and droplet coalescence size of the optimized structure were both larger than those of the initial structure. When the inlet droplet size range was 5–10 µm, after coalescing in the initial structure, the content of 5 µm small droplets was reduced to 3.28%. The content of droplets larger than 500 µm at the outlet reached 85.81%. After structural coalescence through optimization, the content of 5 µm droplets at the outlet significantly decreased to 0.28%, and the content of droplets larger than 500 µm at the outlet reached 88.61%. The coalescence effect of small droplets was greatly improved compared with the initial structure.

- (3)

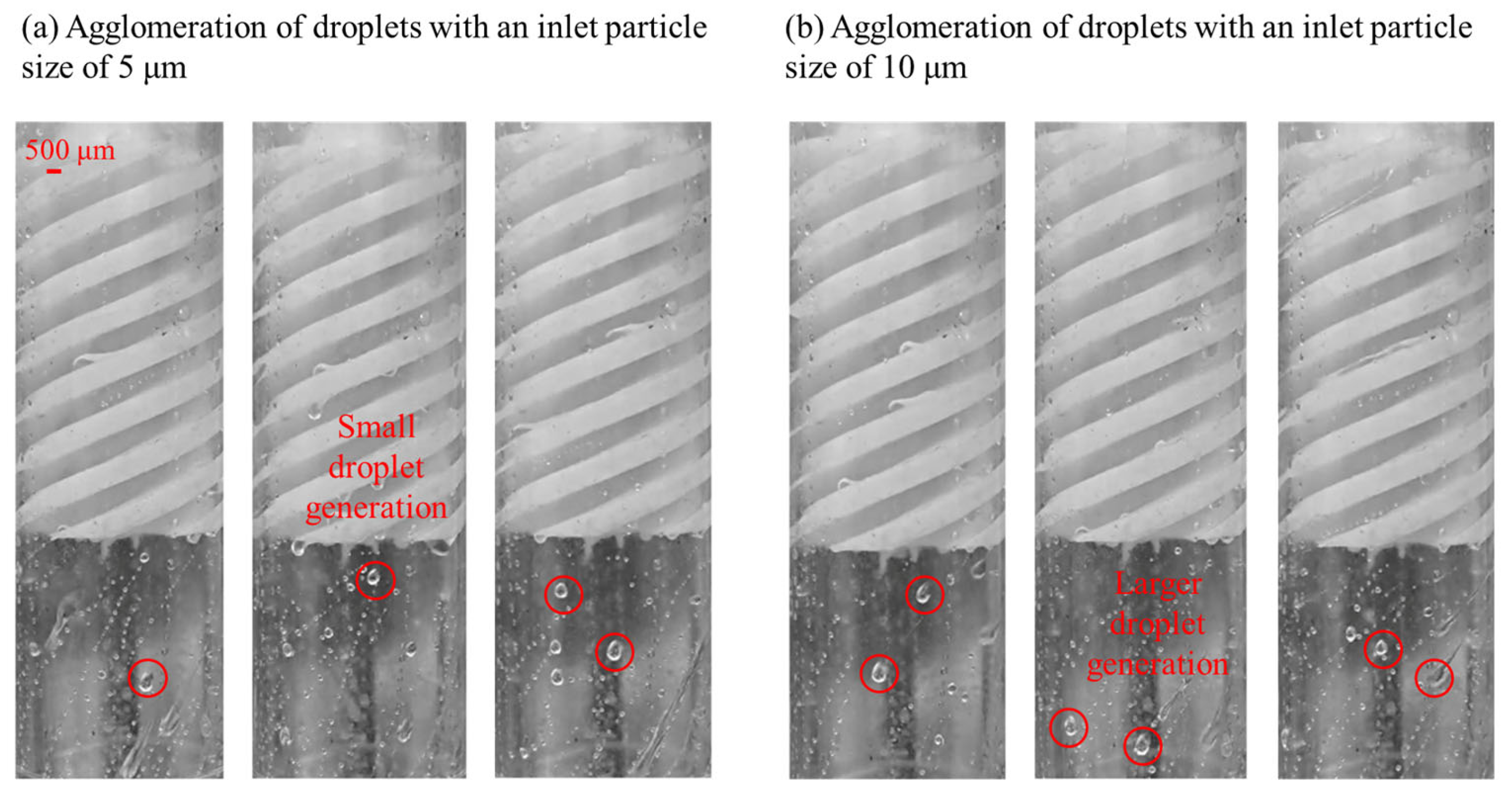

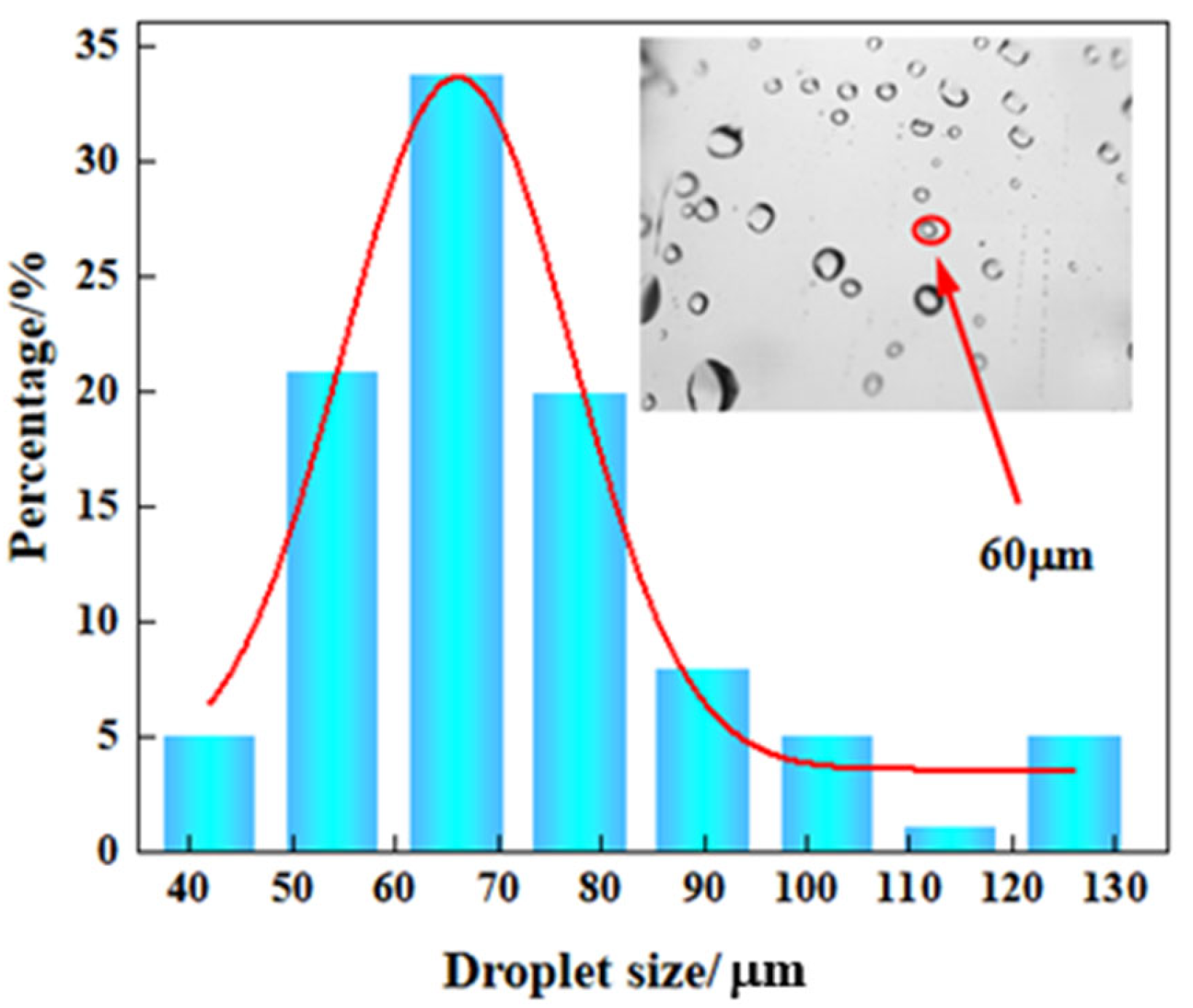

- The coalescence performance of small-sized droplets passing through the optimally structured cyclone coalescer was analyzed using a high-speed camera system. When the size of the inlet droplet was 5 µm, most of the droplets coalesced into large droplets with a size of 50 µm. When the droplet size at the inlet was 10 µm, most of the droplets coalesced into large-sized droplets with a size of 60 µm. The experimental test results were in good agreement with the simulation results. Small-sized liquid droplets formed large-sized liquid droplets in the coalescer cyclone cavity and were eventually discharged from the outlet.

- (4)

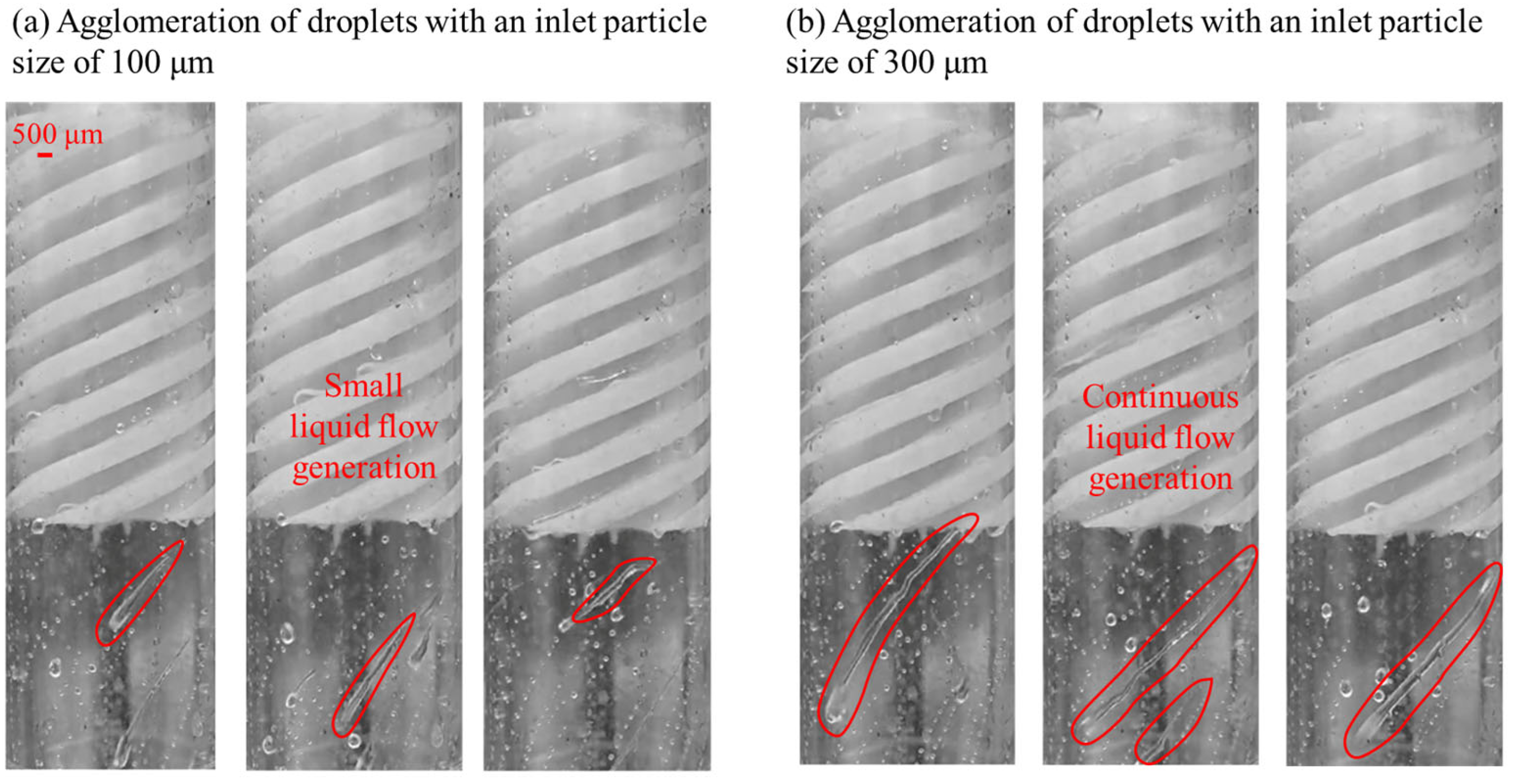

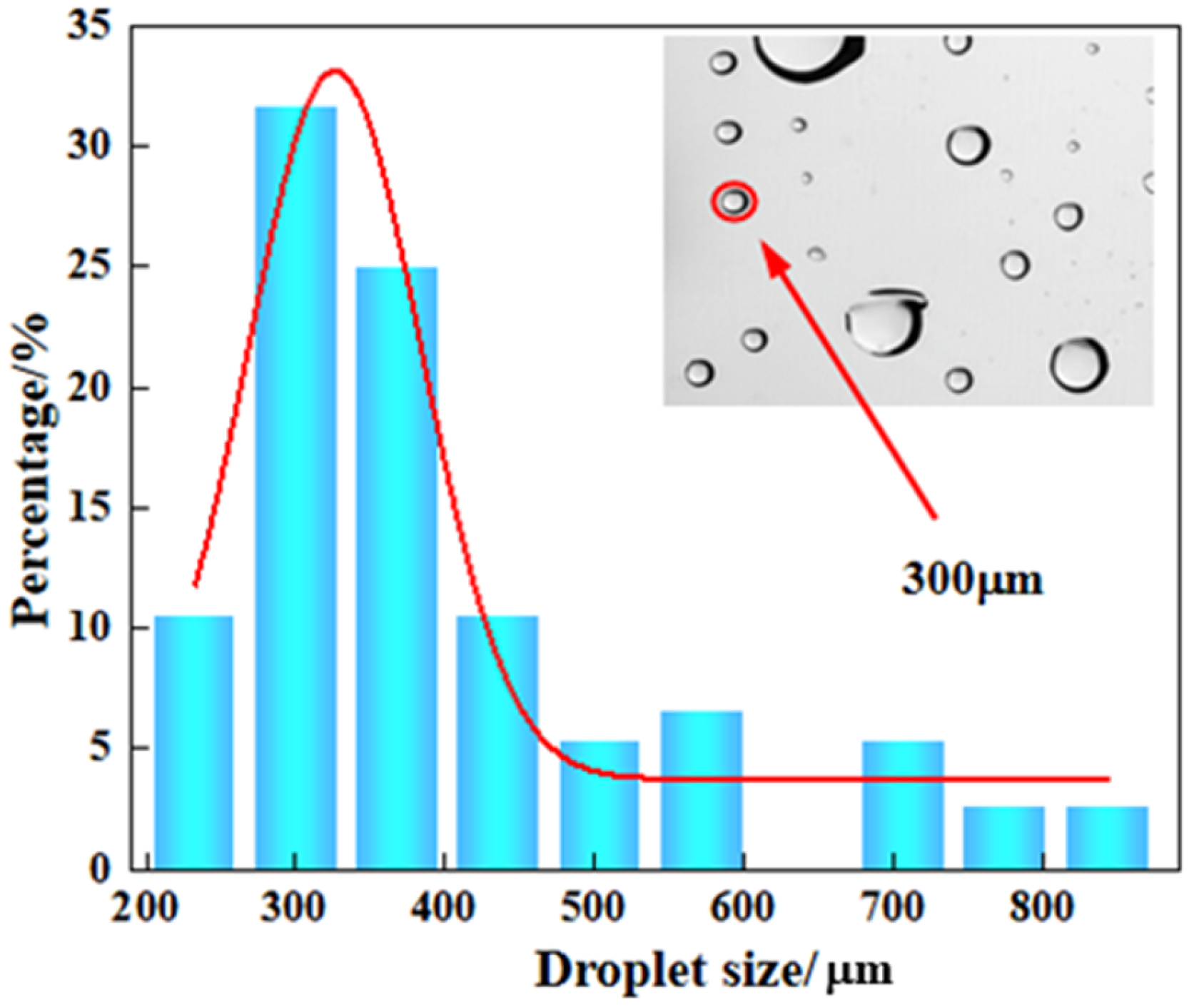

- When the size of the inlet droplet was 300 µm, some of the droplets collided and coalesced into large droplets with a size of 500 µm. Most of the large droplets formed a large surface liquid accumulation flow.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, F.; Huang, K.; Li, H.T.; Huang, C. Analysis and research on the automatic control systems of oil–water baffles in horizontal three-phase separators. Processes 2022, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.Z.K.; Ranjbar, F.; Zare, V.; Homod, R.Z. Unlocking optimal performance and flow level control of three-phase separator based on reinforcement learning: A case study in Basra refinery. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2024, 55, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Pang, H.; Liu, B.Y.; Chen, Y.Q. Application of the ALRW-DDPG algorithm in offshore oil-gas-water separation control. Energies 2024, 17, 4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilala, A.J.; Stanko, M.; Mkinga, O.J. Effects of uncertainty in the design parameters during the design of horizontal gravity oil, gas and water separators. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2025, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Q.; Song, S.F.; Huang, T.; Shen, S.H.; Li, X.P.; Gong, J. Application of Bayesian networks based on Sequential Monte Carlo simulation and physical model in fault diagnosis of horizontal three-phase separator system. Ocean Eng. 2024, 306, 118139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Guan, S.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, M.H. Measurement of a three-dimensional rotating flow field and analysis of the internal oil droplet migration. Energies 2023, 16, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Zhu, H.T.; Wu, H.P.; Zhang, L.T.; Lu, H.; Yang, Q. Combined micromixing and coalescence separation for improved oil desulfurization. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 83, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, R.J.; Xu, P.; Cao, Z.J.; Ren, Z.X. Compact binary coalescence gravitational wave signal counting and separation. Phys. Rev. D 2025, 111, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.A.; Zhang, X.G.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Z.H.; Xie, L.L.; Wang, L.W.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.L.; Chang, Y.L. Cyclone-coalescence separation technology for enhanced droplet removal in natural gas purification process. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 75, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Q.; Wang, T.W.; Li, Y.J.; Wang, C.L.; Zou, J.H.; Wang, Y.K.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.B. Effect and mechanism of drainage measures on gas-liquid coalescence separation performance of a water mist filter. Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 2025, 216, 110424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryul, P.H.; Woonbong, H.; Dukhyun, C. Recent advances on oil-water separation technology. Compos. Res. 2023, 36, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonphimai, P.; Ketnawa, S.; Singh, J.; Tian, J.; Ogawa, Y.; Donlao, N. Sustainable protein recovery from Sacha inchi press cake using cyclone separation: Functional and structural characterization. Future Foods 2025, 12, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpit, P.; Nikhil, K.S.; Arup, K.D. Wettability-driven coalescence behavior of compound droplets over a horizontal surface. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 309, 121468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.B.; Rao, K.J.; Bihola, A.; Adil, S. Standardization and characterization of Mohanthal using response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aditya, V.; Ajeet, S.Y.; Navid, K.; Nam-Trung, N. Acoustically driven vertical coalescence of liquid marbles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 711, 136410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürdaş, M.S.; Dilanb, L. Investigation of the rheological properties of persimmon puree by using response surface methodology. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2025, 17, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Ryu, K.H. Piecewise response surface methodology for enhanced modeling and optimization of complex systems. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 42, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lu, A.J.; Ma, L.K.; Bai, Z.S. Experimental research on enhanced the microfine oil droplets separation using hydrocyclone coupled with fiber coalescence. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 82, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, R.; Josef, G.S. Variance estimation in the change analysis of a linear regression model. Metrika 2001, 54, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominique, L. On the different coalescence mechanisms in foams and in emulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 340, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor | Symbol | Unit | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Level (−1) | Center Point (0) | High Level (+1) | |||

| Spiral channel length L1 | A | mm | 250 | 500 | 750 |

| Length of the cyclone cavity L2 | B | mm | 750 | 1250 | 1750 |

| Outer diameter of the base post D1 | C | mm | 160 | 220 | 280 |

| Experimental Group | x1/mm | x2/mm | x3/mm | d/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 250 | 750 | 220 | 0.364697 |

| 2 | 750 | 750 | 220 | 0.433724 |

| 3 | 250 | 1750 | 220 | 0.305918 |

| 4 | 750 | 1750 | 220 | 0.437964 |

| 5 | 250 | 1250 | 160 | 0.327898 |

| 6 | 750 | 1250 | 160 | 0.447256 |

| 7 | 250 | 1250 | 280 | 0.329935 |

| 8 | 750 | 1250 | 280 | 0.451734 |

| 9 | 500 | 750 | 160 | 0.410868 |

| 10 | 500 | 1750 | 160 | 0.451561 |

| 11 | 500 | 750 | 280 | 0.441344 |

| 12 | 500 | 1750 | 280 | 0.432441 |

| 13 | 500 | 1250 | 220 | 0.431372 |

| 14 | 500 | 1250 | 220 | 0.431372 |

| 15 | 500 | 1250 | 220 | 0.431372 |

| 16 | 500 | 1250 | 220 | 0.431372 |

| 17 | 500 | 1250 | 220 | 0.431372 |

| Type | Degrees of Freedom | Discrete Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 9 | 0.0365 | 0.0041 | 16.61 | 0.0006 |

| x1 | 1 | 0.0279 | 0.0279 | 114.29 | <0.0001 |

| x2 | 1 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 1.43 | 0.2713 |

| x3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1637 | 0.6978 |

| x1x2 | 1 | 0.0003 | 0.0003 | 1.12 | 0.3256 |

| x1x3 | 1 | 1.489 × 10−6 | 1.489 × 10−6 | 0.0061 | 0.9399 |

| x1x4 | 1 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 2.52 | 0.1563 |

| 1 | 0.0073 | 0.0073 | 29.84 | 0.0009 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1853 | 0.6798 | |

| 1 | 1.486 × 10−6 | 1.486 × 10−6 | 0.0061 | 0.9400 | |

| Residual | 7 | 0.0017 | 0.0002 | ||

| Lack of fit | 3 | 0.0017 | 0.0006 | ||

| Pure error | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cor Total | 16 | 0.0382 |

| Statistic Indicators | Value | Statistic Indicators | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Std. Dev. | 0.0156 | R2 | 0.9553 |

| Mean | 0.4131 | Adjusted R2 | 0.8978 |

| C.V. | 3.78 | Predicted R2 | 0.8844 |

| Adeq Precision | 11.3613 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Xing, L. Process Design for Optimizing Small Particle Diameter Light Hydrocarbon Recovery from Tight Gas Fields. Processes 2025, 13, 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123884

Li J, Xing L. Process Design for Optimizing Small Particle Diameter Light Hydrocarbon Recovery from Tight Gas Fields. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123884

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jianli, and Lei Xing. 2025. "Process Design for Optimizing Small Particle Diameter Light Hydrocarbon Recovery from Tight Gas Fields" Processes 13, no. 12: 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123884

APA StyleLi, J., & Xing, L. (2025). Process Design for Optimizing Small Particle Diameter Light Hydrocarbon Recovery from Tight Gas Fields. Processes, 13(12), 3884. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123884