Study of the Maximum Pressures in an Evaporator of a Direct Expansion Heat Pump Using R744 Assisted by Solar Energy

Abstract

1. Introduction

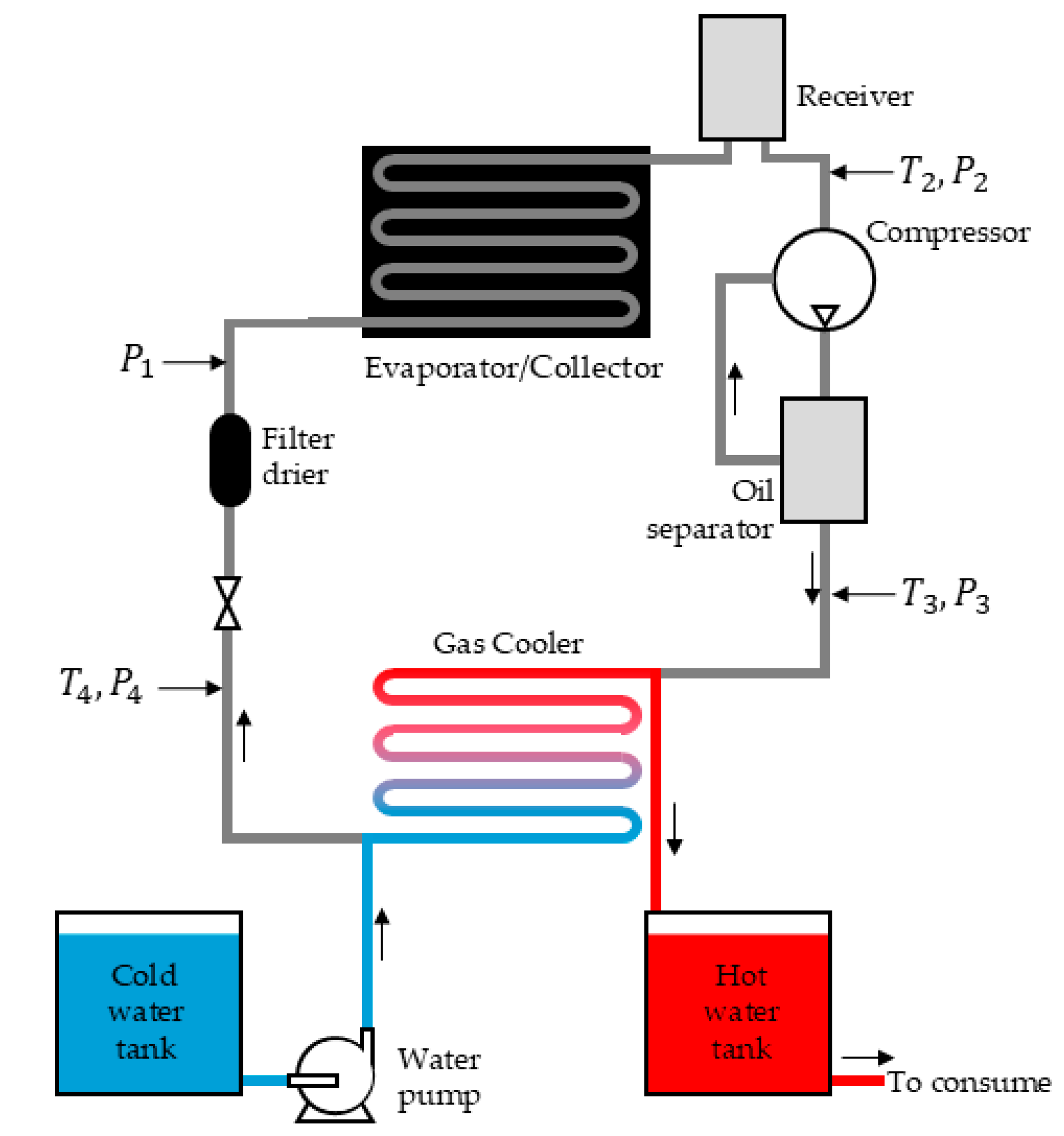

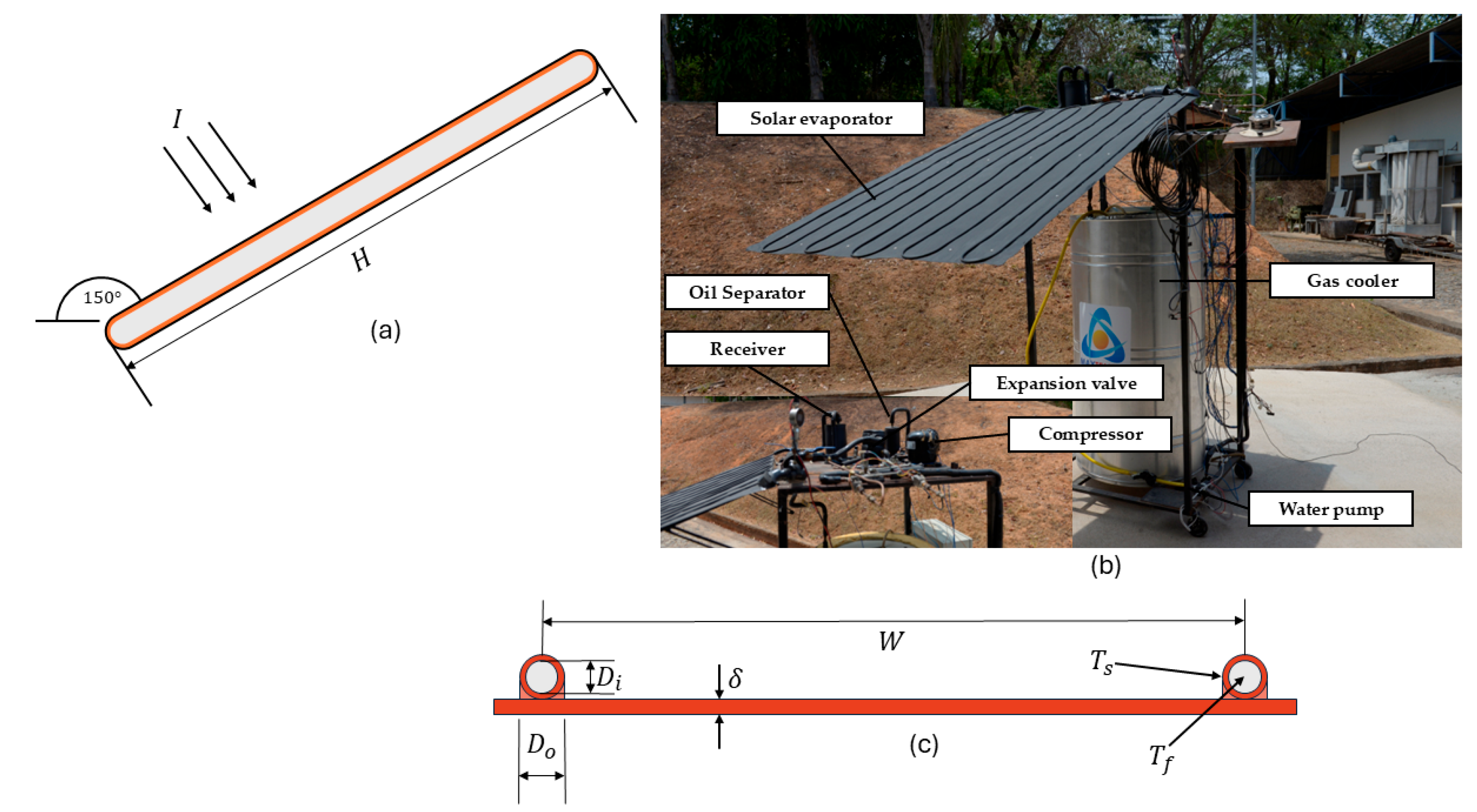

2. System Description

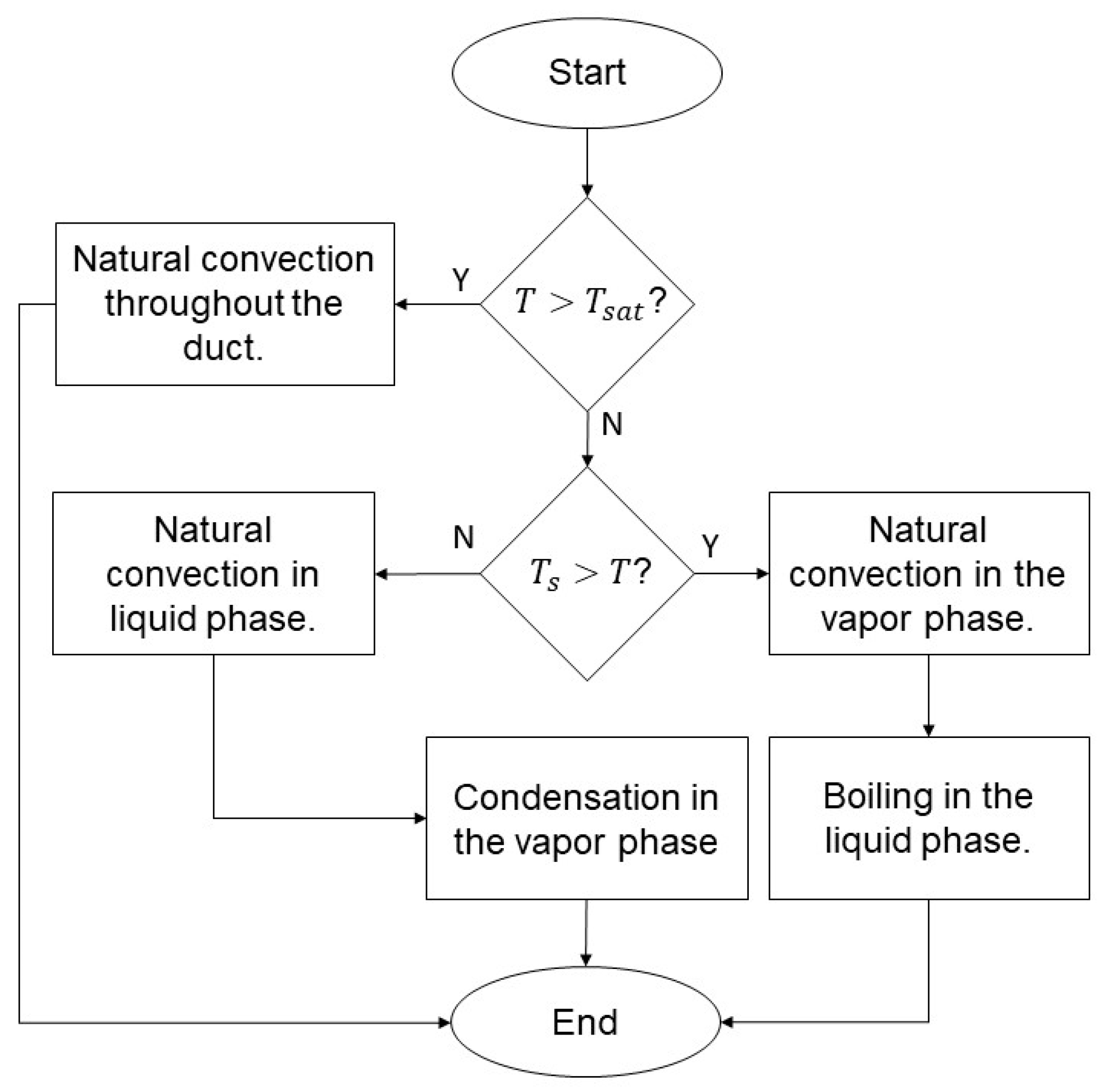

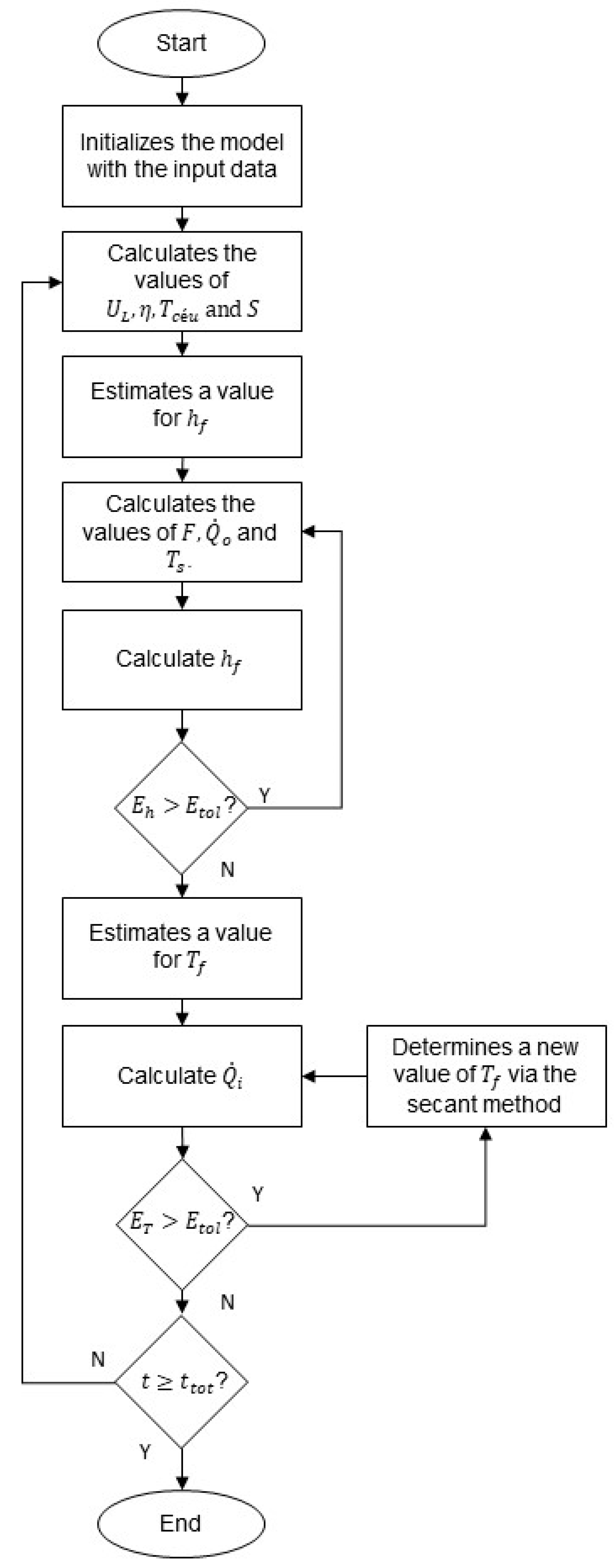

3. Mathematical Model

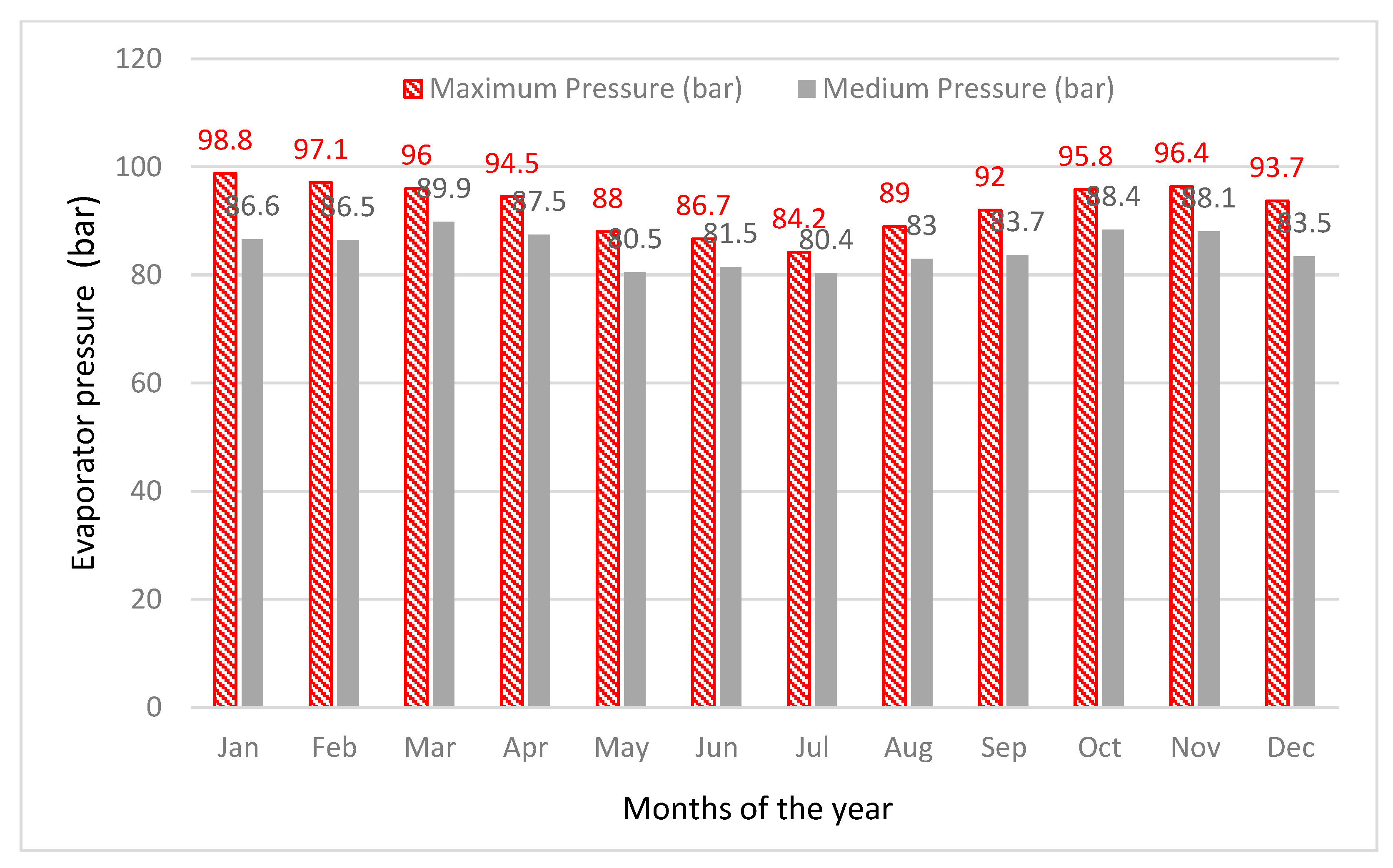

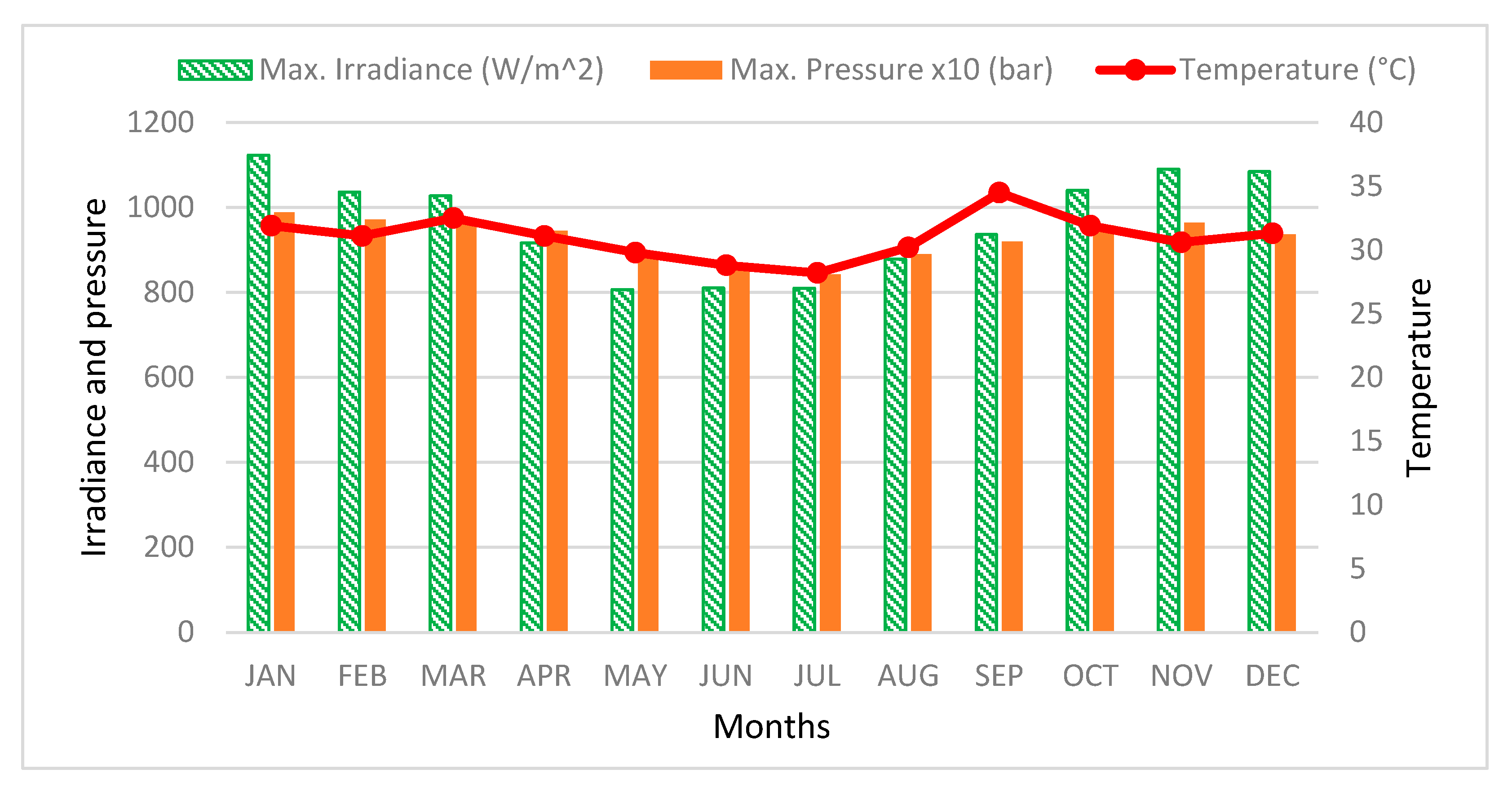

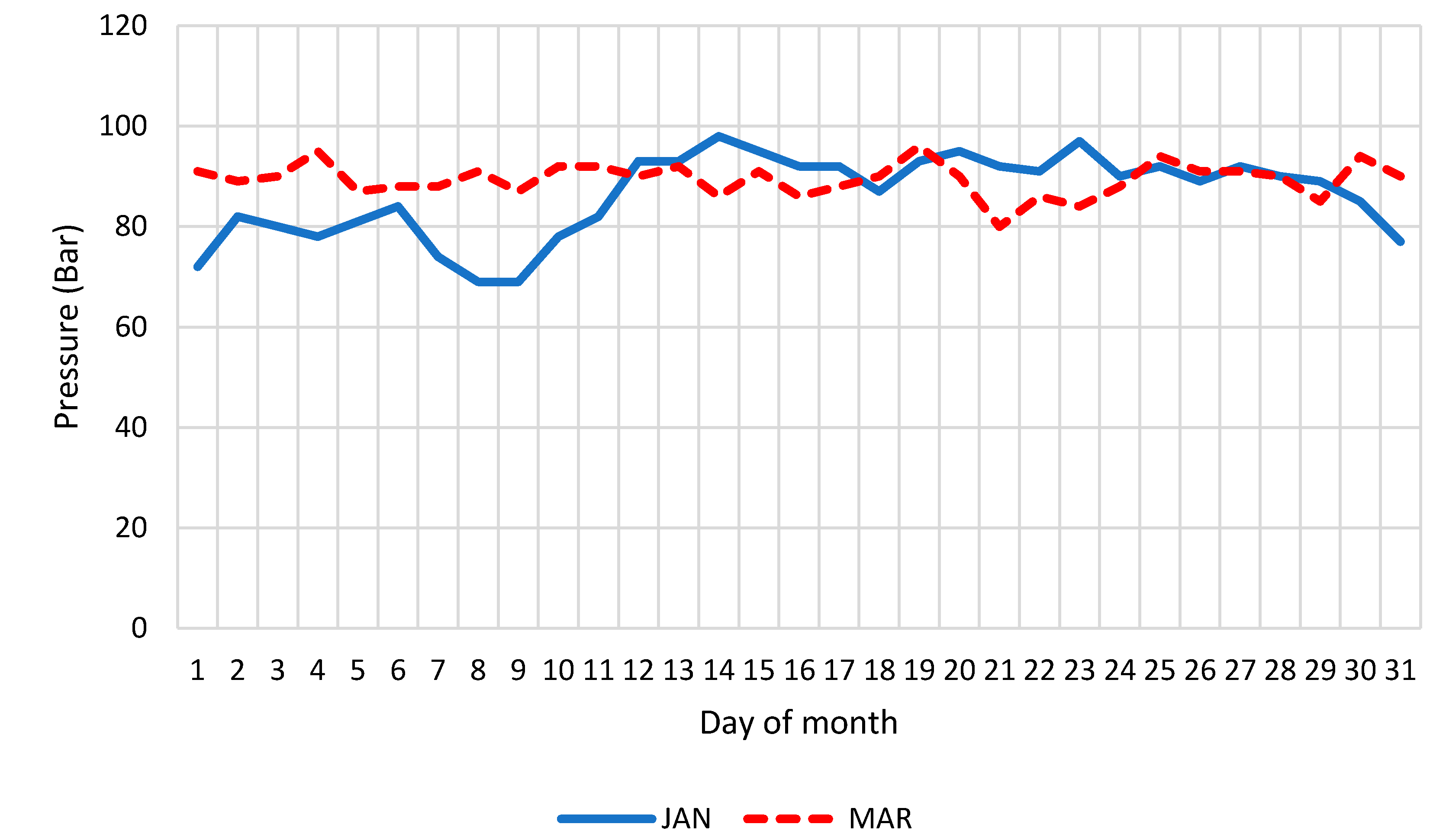

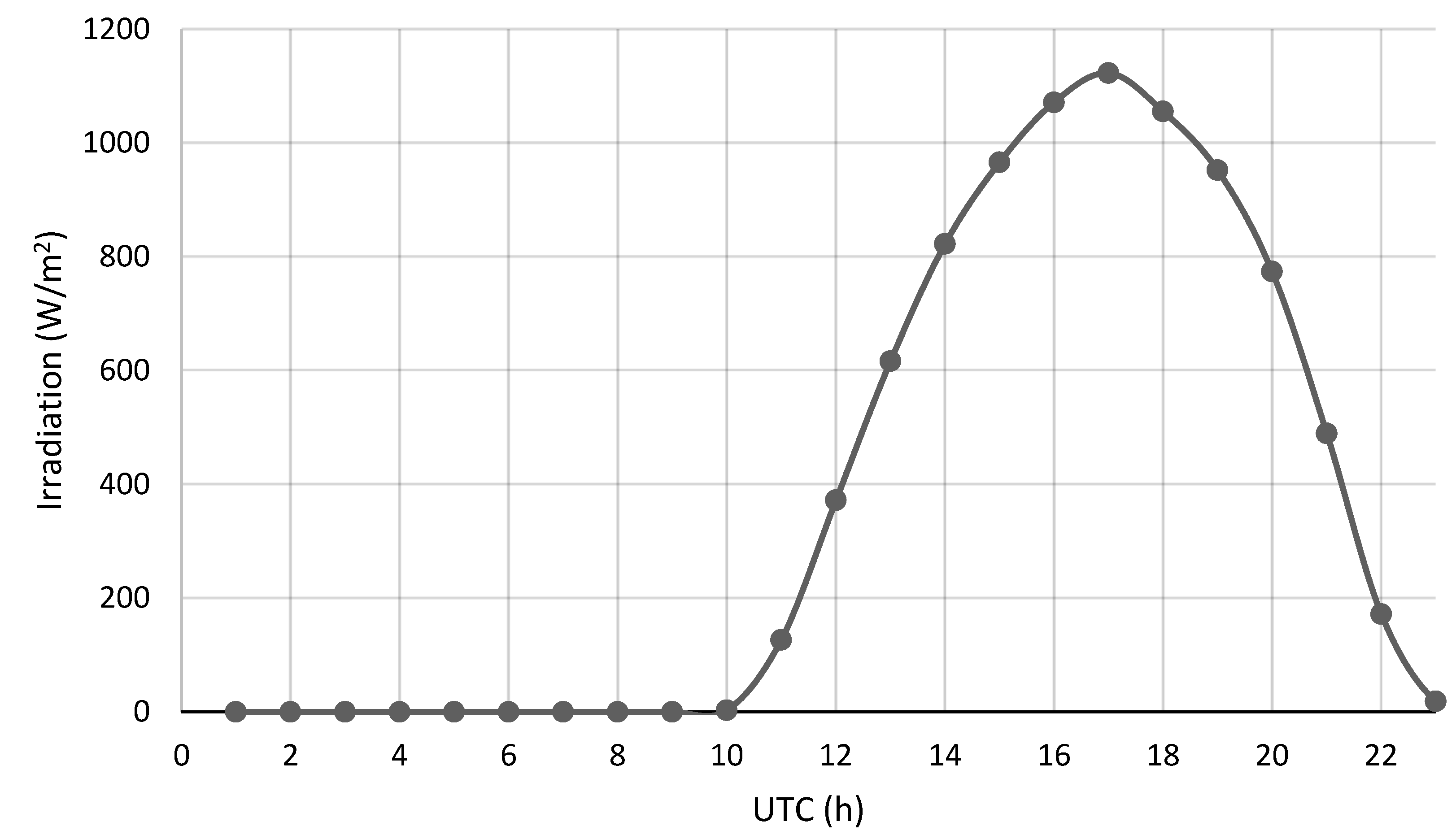

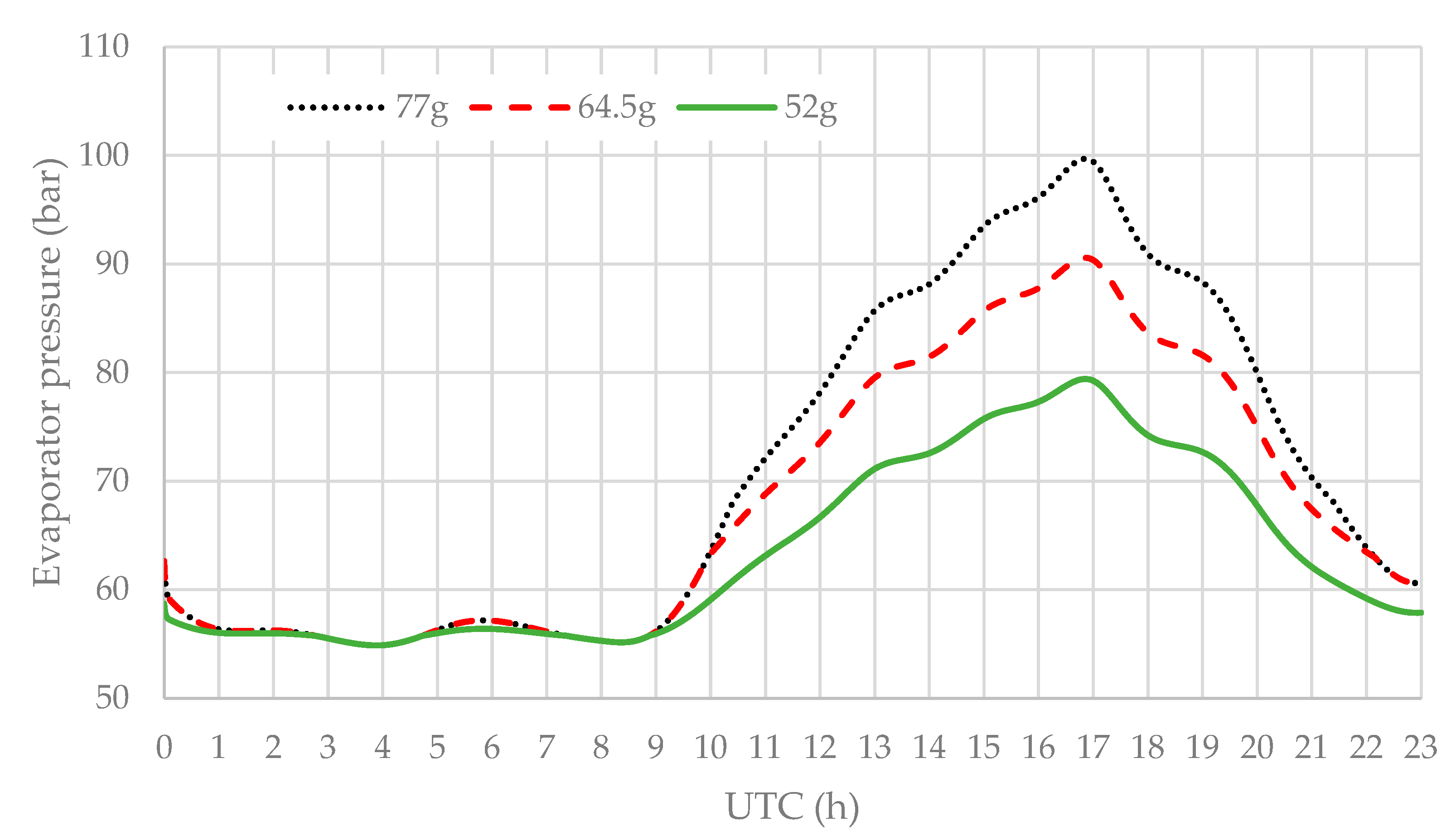

4. Results

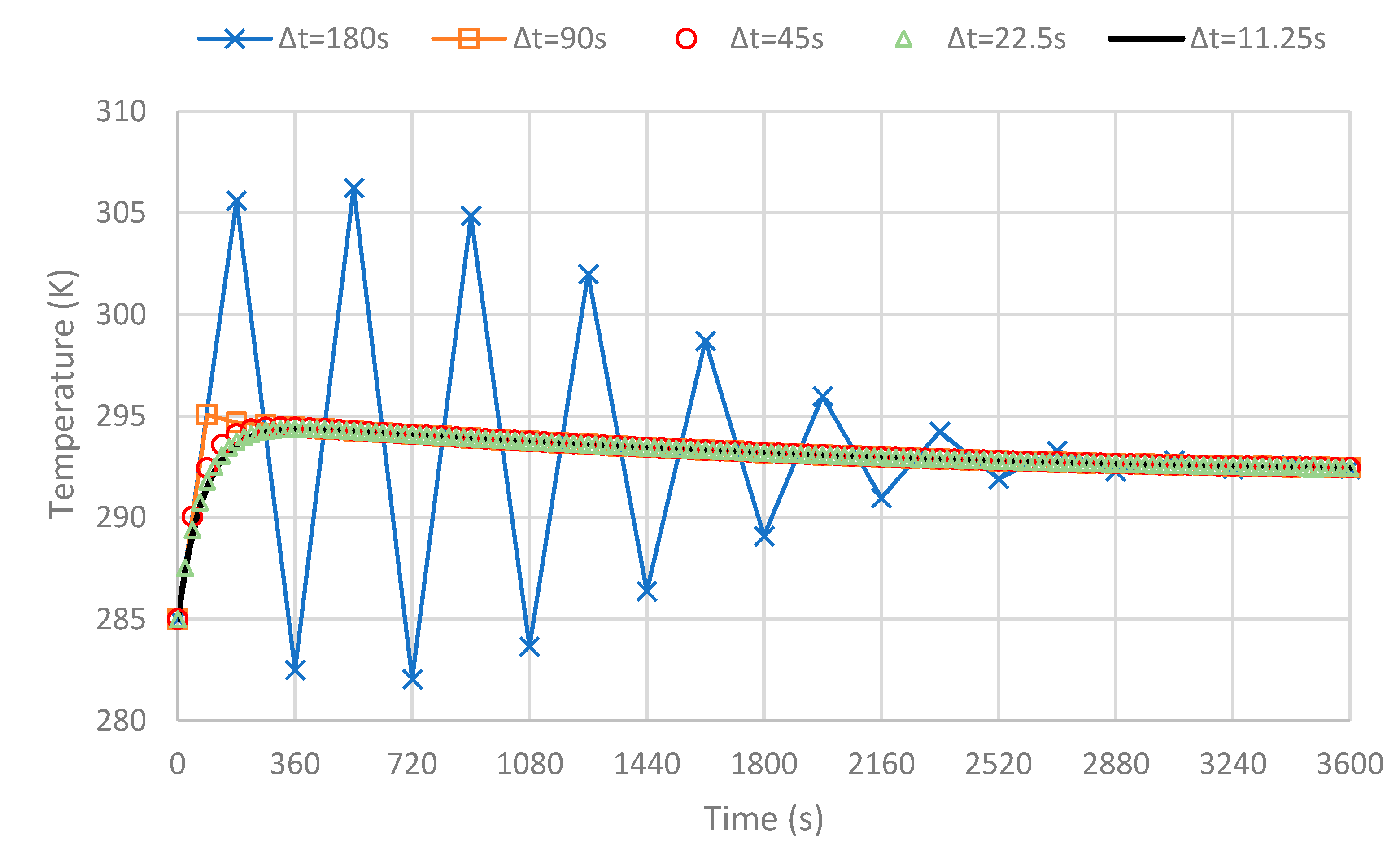

4.1. Grid Test

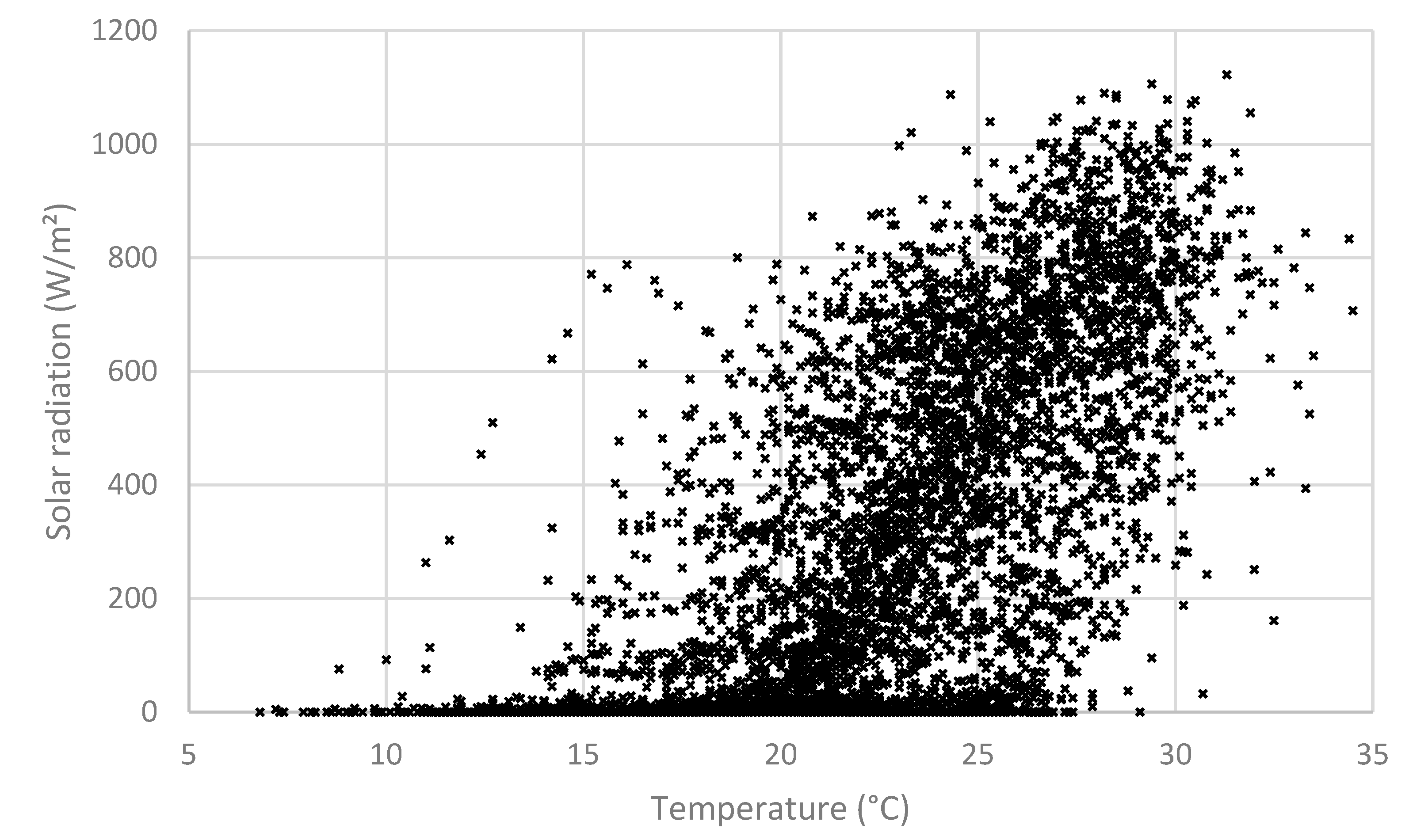

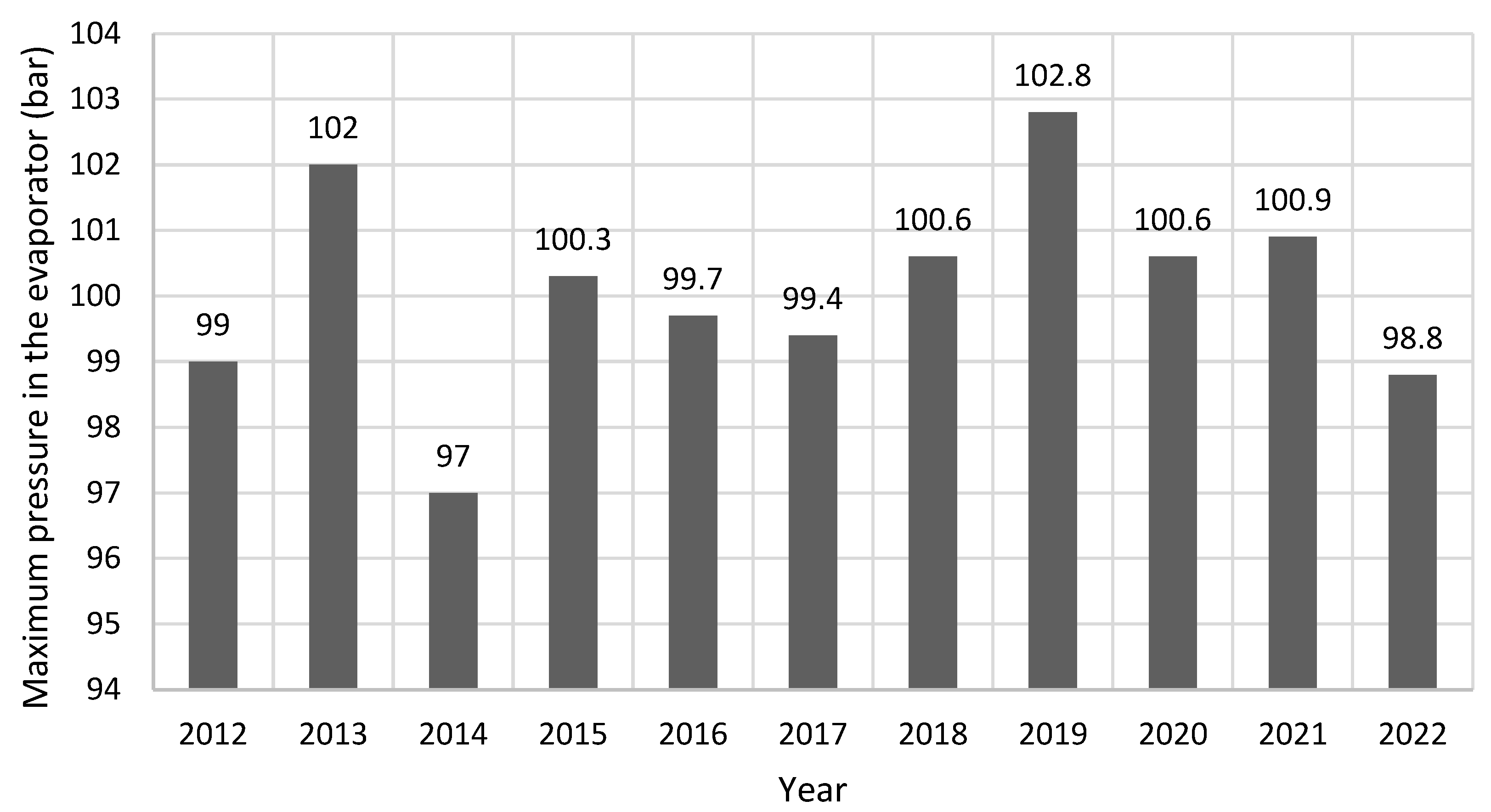

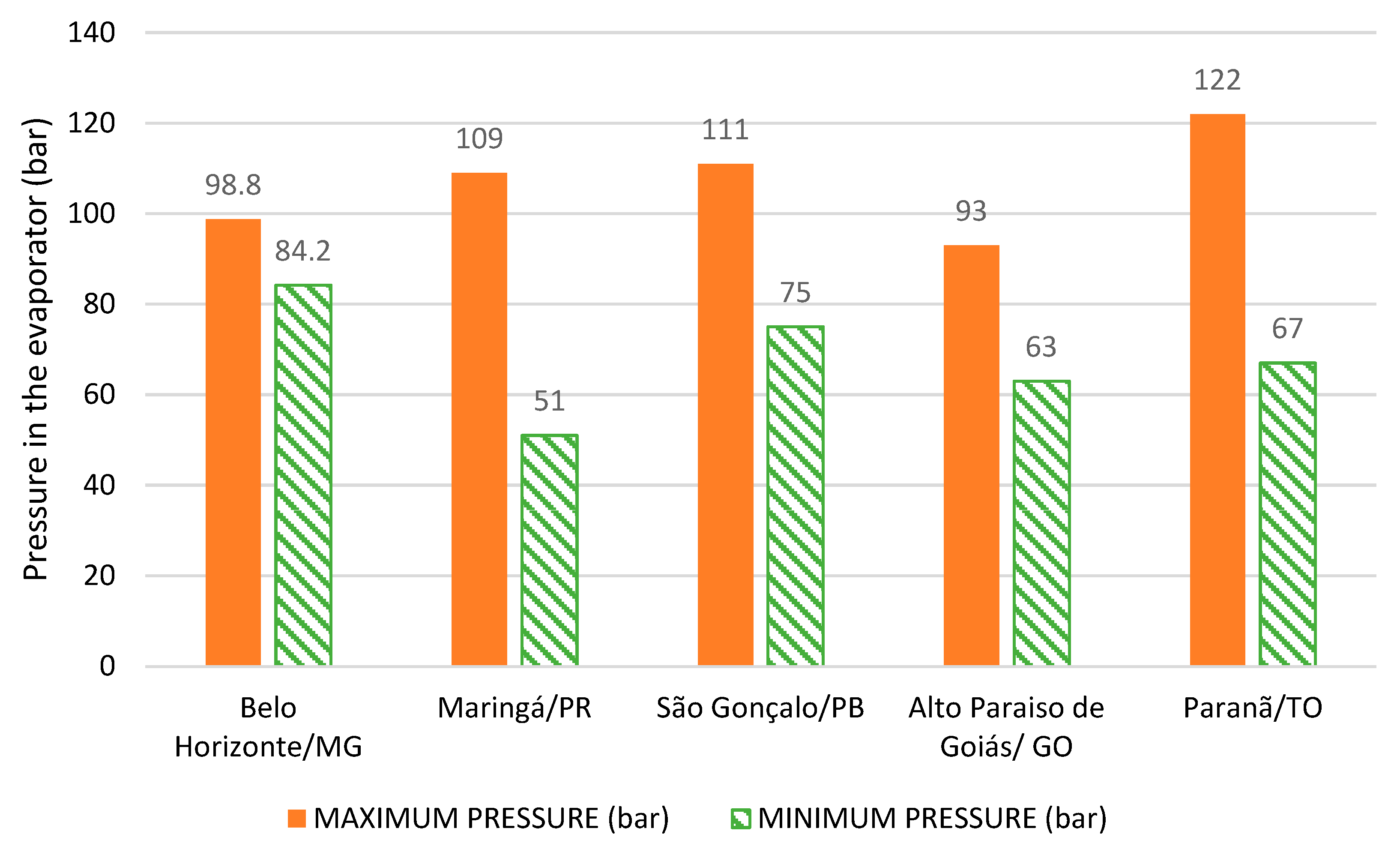

4.2. Effect of Solar Radiation on the DX-SAHP Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Latin letters | |

| Heat transfer rate [W] | |

| A | Area [m2] |

| B | Auxiliary parameter [dimensionless] |

| C | Thermal conductance of solder [W/K] |

| c | Specific heat [J/kgK] |

| D | Diameter [m] |

| E | Erro [%] |

| F | Fin efficiency [dimensionless] |

| h | Convective heat transfer coefficient [W/m2K] |

| H | Height [m] |

| I | Solar irradiance [W/m2] |

| k | Thermal conductivity [W/mK] |

| L | Length [m] |

| m | Mass [kg] |

| Nu | Nusselt number [dimensionless] |

| Ra | Rayleigh number [dimensionless] |

| S | Net radiation absorbed [W/m2] |

| T | Temperature [K] |

| t | Time [s] |

| u | Internal energy [kJ/kgK] |

| U | Overall heat transfer coefficient [W/m2K] |

| V | Velocity [m/s] |

| W | Distance between the tubes [m] |

| Greek letters | |

| α | Solar absorptance [dimensionless] |

| ε | Emissivity [dimensionless] |

| ρ | Density [kg/m3] |

| σ | Stefan–Boltzmann constant [W/m2K4] |

| δ | Fin thickness [m] |

| η | Fin efficiency [dimensionless] |

| ϴ | Angle [°] |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Air |

| sky | Sky |

| cr | Critical |

| cu | Copper |

| dp | Dew point |

| e | Evaporator |

| f | Fluid |

| h | Convective coefficient |

| i | Internal |

| L | Losses |

| o | External |

| T | Temperature |

| tol | Tolerated |

| tot | Total |

| vert | Vertical |

| wd | Wind |

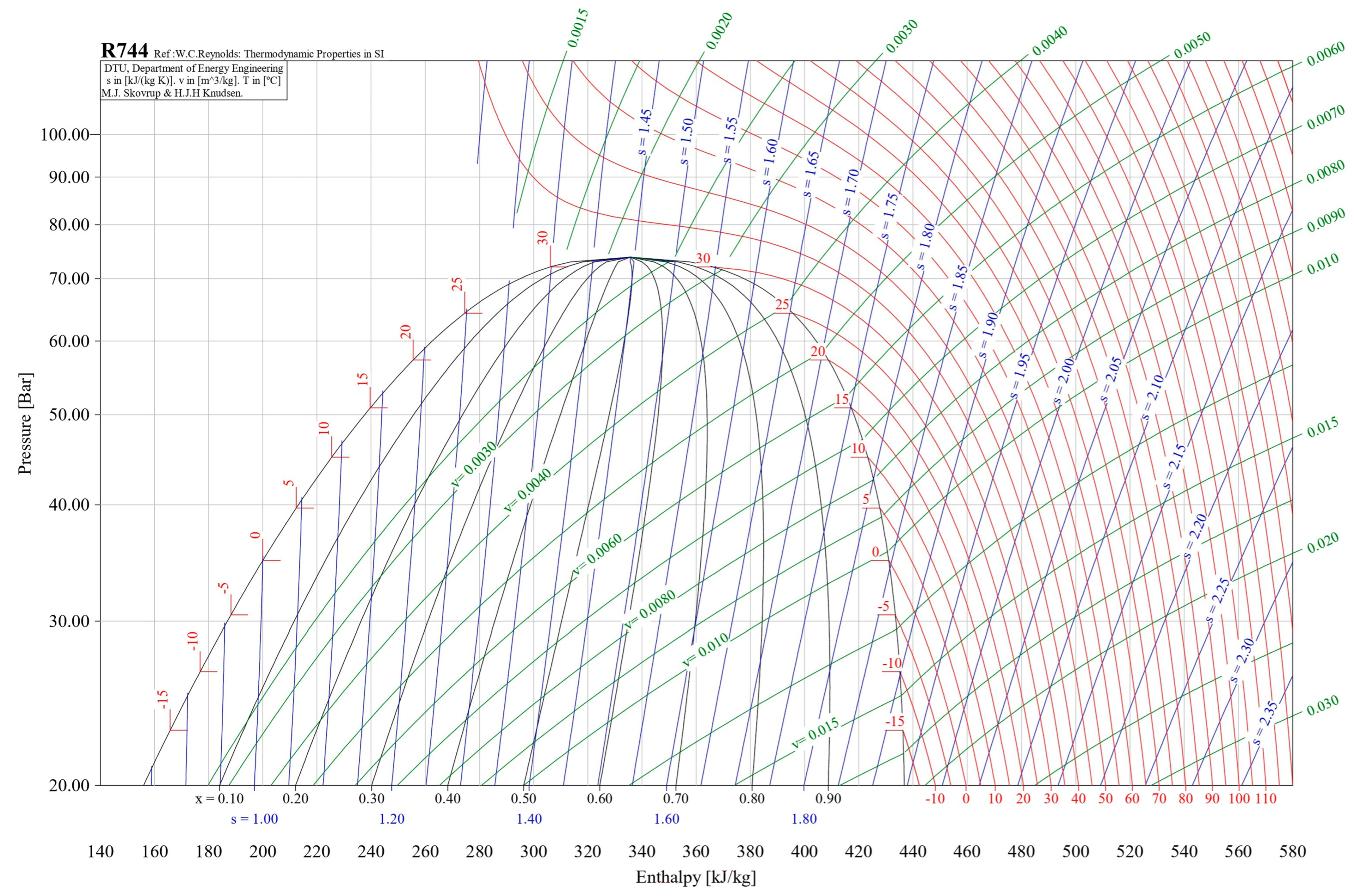

Appendix A. R744 Pressure vs. Specific Enthalpy Diagram

References

- Empresa de Pesquisa Energética. Balanço Energético Nacional 2024. EPE. 2021. Available online: https://www.epe.gov.br/sites-pt/publicacoes-dados-abertos/publicacoes/PublicacoesArquivos/publicacao-819/topico-715/BEB_Summary_Report_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Blázquez, C.S.; Nieto, I.M.; García, J.C.; García, P.C.; Martín, A.F.; González-Aguilera, D. Comparative analysis of ground source and air source heat pump systems under different conditions and scenarios. Energies 2023, 16, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, S.I.D.M.; Diniz, H.A.G.; Faria, R.N.D.; de Oliveira, R.N. Design and Experimental Evaluation of a Controller for a Direct-Expansion Solar-Assisted Heat Pump with Propane. Processes 2025, 13, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Pu, J.; Ma, S.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y. Holistic Sustainability Assessment of Solar Ground Source Heat Pump Systems: Integrating Life Cycle Assessment, Carbon Emissions and Emergy Analyses. Sustainability 2025, 17, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buker, M.S.; Riffat, S.B. Solar assisted heat pump systems for low temperature water heating applications: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporn, P.; Ambrose, E. The heat pump and solar energy. In Proceedings of the World Symposium on Applied Solar Energy, Tucson, AZ, USA, 1–5 November 1955; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R.; Threlkeld, J. Design and economics of solar energy heat pump system. Heat. Pip. Air Cond. USA 1954, 26, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, W.M. Numeric Model of a Direct Expansion Solar Assisted Heat Pump Water Heater Operating with Low GWP Refrigerants (R1234yf, R290, R600a and R744) for Replacement of R134a. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti, E.; Azzolin, M.; Girotto, S.; Del Col, D. Performance and control of a CO2 dual source solar assisted heat pump with a photovoltaic-thermal evaporator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 218, 119286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, G. Revival of carbon dioxide as a refrigerant. Int. J. Refrig. 1994, 17, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.N.; Faria, R.N.; Antonanzas-Torres, F.; Machado, L.; Koury, R.N.N. Dynamic model and experimental validation for a gas cooler of a CO2 heat pump for heating residential water. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2016, 22, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, S.N.; Paulino, T.F.; Machado, L.; Duarte, W.M. Economic analysis and design optimization of a direct expansion solar assisted heat pump. Sol. Energy 2019, 188, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, S.N.; Paulino, T.F.; Soares, C.P.; Duarte, W.M.; Machado, L.; Nunes, R.O. Mass flow characteristics of CO2 operating in a transcritical cycle flowing through a needle expansion valve in a direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.; Gagrani, V.; Abdel-Salam, T. Solar-assisted heat pump–a sustainable system for low temperature water heating applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 77, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.G.; Torres-Reyes, E. Experiments on a solar-assisted heat pump and an exergy analysis of the system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 22, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradeshi, L.; Mohanraj, M.; Srinivas, M.; Jayaraj, S. Exergy analysis of direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pumps working with R22 and R433a. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 134, 2223–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Wu, J.; Xu, Y. Experimental performance analysis and optimization of a direct expansion solar-assisted heat pump water heater. Energy 2007, 32, 1361–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T.T.M.; de Paula, C.H.; Maia, A.A.T.; de Freitas Paulino, T.; de Oliveira, R.N. Experimental assessment of a CO2 direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump operating with capillary tubes and air-solar heat source. Sol. Energy 2021, 218, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.P.; Diniz, H.A.G.; Duarte, W.M.; Machado, L. Experimental study and semi-empirical model of a thermostatic expansion valve of a R290 direct-expansion solar heat pump. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 163, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Sumathy, K.; Gong, J.; Khan, S.U. Performance study on solar assisted heat pump water heater using CO2 in a transcritical cycle. In International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality; Citeseer: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, S.K.; Shen, J.Y. Thermal performance of a direct expansion solar-assisted heat pump. Sol. Energy 1984, 33, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.K.; Chen, D.; Kheireddine, A. Thermal performance of a variable capacity direct expansion solar-assisted heat pump. Energy Convers. Manag. 1998, 39, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Miura, N.; Wang, K. Performance of a heat pump using direct expansion solar collectors. Sol. Energy 1999, 65, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Reyes, E.; Gortari, J.C. Optimal performance of an irreversible solar-assisted heat pump. Exergy Int. J. 2001, 1, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlader, M.; Chou, S.; Ullah, M. The performance of a solar assisted heat pump water heating system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2001, 21, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyng, J.; Lee, C.; Huang, B. Performance analysis of a solar-assisted heat pump water heater. Sol. Energy 2003, 74, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Sumathy, K.; Wang, R. Study on a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump water heating system. Int. J. Energy Res. 2003, 27, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Miura, N.; Takano, Y. Studies of heat pumps using direct expansion type solar collectors. J. Sol. Energy Eng. 2005, 127, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.; Wang, R. Performance of a multi-functional direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump system. Sol. Energy 2006, 80, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Deng, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Simulation of a photovoltaic/thermal heat pump system having a modified collector/evaporator. Sol. Energy 2009, 83, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.T.; Pei, G.; Fong, K.; Lin, Z.; Chan, A.; He, M. Modeling and application of direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump for water heating in subtropical Hong Kong. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q. Thermal performance analysis of a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump water heater. Energy 2011, 36, 6830–6838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rodríguez, A.; González-Gil, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Garcia-Hernando, N. Theoretical model and experimental validation of a direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump for domestic hot water applications. Energy 2012, 45, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Seara, J.; Piñeiro, C.; Dopazo, J.A.; Fernandes, F.; Sousa, P.X. Experimental analysis of a direct expansion solar assisted heat pump with integral storage tank for domestic water heating under zero solar radiation conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wu, Q.; Li, J.; Kong, X. Effects of refrigerant charge and structural parameters on the performance of a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 73, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Dai, Y.; Novakovic, V.; Wu, J.; Wang, R. Performance comparison of direct expansion solar-assisted heat pump and conventional air source heat pump for domestic hot water. Energy Procedia 2015, 70, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Yu, J. Simulation analysis on dynamic performance of a combined solar/air dual source heat pump water heater. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 120, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, L.; Yang, Y. Modeling evaluation of a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump water heater using R410A. Int. J. Refrig. 2017, 76, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.; Riffat, S.; Omer, S. Low-temperature solar-plate-assisted heat pump: A developed design for domestic applications in cold climate. Int. J. Refrig. 2017, 81, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, H.A.G. Estudo Comparativo Da Eficiência Energética de Uma Bomba de Calor Assistida Por Energia Solar Operando Com Condensadores Por Imersão E Coaxial. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rabelo, S.N.; Paulino, T.F.; Duarte, W.M.; Sawalha, S.; Machado, L. Experimental analysis of the influence of water mass flow rate on the performance of a CO2 direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump. Int. J. Chem. Mol. Nucl. Mater. Metall. Eng. 2018, 12, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Sun, P.; Dong, S.; Jiang, K.; Li, Y. Experimental performance analysis of a direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump water heater with R134a in summer. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 91, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, J. Experimental investigation on a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump water heater using r290 with micro-channel heat transfer technology during the winter period. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 113, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, W.M.; Rabelo, S.N.; Paulino, T.F.; Pabón, J.J.; Machado, L. Experimental performance analysis of a co2 direct-expansion solar assisted heat pump water heater. Int. J. Refrig. 2021, 125, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, H.A.G.; de Melo Resende, S.I.; Maia, A.A.T.; Machado, L.; de Oliveira, R.N. Development, experimental validation through infrared thermography and applications of a mathematical model of a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump with R290 based on energy, exergy, economic and environmental (4E) analyses. Sol. Energy 2023, 260, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, B.; Li, S.; Mwesigye, A. Investigation of the thermodynamic performance of a direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump under very cold climatic conditions with and without glazing. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 158, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.O.; Paulino, T.F.; Machado, L.; Maia, A.A.; Duarte, W.M. Optimal high-pressure correlation for transcritical CO2 cycle in direct expansion solar assisted heat pumps. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Vaishak, S.; Bhale, P.V.; Rathod, M.K. Analysis of water and refrigerant-based PV/T systems with double glass PV modules: An experimental and computational approach. Sol. Energy 2024, 268, 112296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Song, Z.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Q. Enhancing thermal performance: The evolution and future of solar air heaters with baffles. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 75, 107163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, M.; Ramalingam, S.; Natesan, P.; Sampath, S. CFD-based optimization of solar water heating systems: Integrating evacuated tube and flat plate collectors for enhanced efficiency. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 69, 106017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichana, C.; Kiatsiriroat, T.; Nuntaphan, A. Comparison of conventional flat-plate solar collector and solar boosted heat pump using unglazed collector for hot water production in small slaughterhouse. Heat Transf. Eng. 2010, 31, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.; De Witt, D.; Bergman, T. Fundamentos de Transferência de Calor E de Massa, 6th ed.; LTC: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gliah, O.; Kruczek, B.; Etemad, S.G.; Thibault, J. The effective sky temperature: An enigmatic concept. Heat Mass Transf. 2011, 47, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, P.; Fromberg, R. The thermal radiance of clear skies. Sol. Energy 1982, 29, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Saturated nucleate pool boiling-a simple correlation. In Proceedings of the 1st UK National Heat Transfer Conference, Yorkshire, UK, 3–5 July 1984; pp. 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Hollands, K.; Unny, T.; Raithby, G.; Konicek, L. Free convective heat transfer across inclined air layers. J. Heat Transfer 1976, 98, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengel, Y.A.; Ghajar, A.J. Tranferência de Calor e Massa; AMGH Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shewen, E.; Hollands, K.; Raithby, G. Heat transfer by natural convection across a vertical air cavity of large aspect ratio. J. Heat Transf. 1996, 118, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mullick, S. Wind heat transfer coefficient in solar collectors in outdoor conditions. Sol. Energy 2010, 84, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals (SI Edition); American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, I.H.; Wronski, J.; Quoilin, S.; Lemort, V. Pure and pseudo-pure fluid thermophysical property evaluation and the open-source thermophysical property library coolprop. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapra, S.C.; Canale, R.P. Numerical Methods for Engineers; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Humia, G.M.; Duarte, W.M.; Pabon, J.J.G.; Paulino, T.F.; Machado, L. Experimental study and simulation model of a direct expansion solar assisted heat pump to CO2 for water heating: Inventory, coefficient of performance and total equivalent warming impact. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.; Goldschmidt, V. Cycling characteristics of a residential air conditioner-modeling of shutdown transients. ASHRAE Trans. 1986, 92, 186–202. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Collector Type | Collector Size (m2) | Refrigerant | COP | Study | Maximum Pressure Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Experimental | ||||||

| Chaturvedi and Shen (1984) [21] | UFP | 3.4 | R12 | 2.0–3.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Chaturvedi et al. (1998) [22] | UFP | 3.5 | R12 | 2.5–4.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Ito et al. (1999) [23] | UFP | 3.2 | R22 | 2.0–8.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Torres-Reyes and Gortari (2001) [24] | UFP | 4.5 | R22 | 5.6–4.4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Hawlader et al. (2001) [25] | UFP | 3.0 | R134a | 4.0–9.0 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Chyng et al. (2003) [26] | UFP | 1.9 | R134a | 1.7–2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kuang et al. (2003) [27] | UFP | 2.0 | R22 | 4.0–6.0 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Ito et al. (2005) [28] | PVT | 1.9 | R22 | 4.5–6.5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kuang and Wang (2006) [29] | UFP | 10.5 | R22 | 2.6–3.3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Li et al. (2007) [17] | UFP | 4.2 | R22 | 5.21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Xu et al. (2009) [30] | PVT | 2.3 | R22 | 4.9–5.1 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Chow et al. (2010) [31] | UFP | 12 | R134a | 6.5–10.0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Kong et al. (2011) [32] | UFP | 4.2 | R22 | 5.2–6.6 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Moreno-Rodríguez et al. (2012) [33] | UFP | 5.6 | R134a | 1.7–2.9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Islam et al. (2012) [20] | CFP | - | R744 | 1.5–2.7 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Fernández- Seara et al. (2012) [34] | UFP | 1.6 | R134a | 2.0–4.0 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Zhang et al. (2014) [35] | UFP | 4.2 | R22 | 3.5–6.0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Sun et al. (2015) [36] | UFP | 2.0 | - | 4.0–5.5 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Deng and Yu (2016) [37] | CFP | 2.5 | R134a | 3.9–6.2 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Kong et al. (2017) [38] | UFP | 4.2 | R410a | 5.2–6.6 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Mohamed et al. (2017) [39] | UFP | 4.2 | R407C | 5.2–6.6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Diniz (2017) [40] | UFP | 1.6 | R134a | 2.1–2.9 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Rabelo et al. (2018) [41] | UFP | 1.6 | R744 | 3.5–5.5 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kong et al. (2018) [42] | UFP | 2.1 | R134a | 3.6–5.6 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Rabelo et al. (2019) [12] | UFP | 1.57 | R744 | 2.58 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kong et al. (2020) [43] | UFP | 2.1 | R290 | 2.12–4.43 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Duarte et al. (2021) [44] | UFP | 1.57 | R744 | 3.2–5.4 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Diniz et al. (2023) [45] | UFP | 1.6 | R290 | 2.1–2.9 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Zanetti et al. (2023) [9] | PVT | 4.9 | R744 | 2.94–4.4 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Abbasi et al. (2024) [46] | CFP | 2.3 | R134a | 2.6–3.9 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Reis et al. (2024) [47] | UFP | 1.57 | R744 | 1.8–2.8 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Sharma et al. (2024) [48] | PVT | 0.65 | R134a | 3.75 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Parameter | Valor |

|---|---|

| Tube and fins metal | Copper |

| Outside diameter of the tube | |

| Tube inner diameter | |

| Pipe length | |

| Evaporator height | |

| Distance between tubes | |

| Fin thickness | |

| Plate area | |

| Copper conductivity [52] | |

| Emissivity |

| Property | Value/Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Chemical formula | CO2 |

| Critical temperature | 31.1 °C |

| Critical pressure | 73.8 bar |

| Boiling point (at 1 atm) | −78 °C |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | 1 |

| Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP) | 0 |

| Flammability | Non-flammable |

| Toxicity | Non-toxic |

| City/State | Maximum Pressure (bar) | Acceptable Limit |

|---|---|---|

| Alto Paraíso de Goiás/GO | 93 | 71.5% |

| Belo horizonte/MG | 98.8 | 81.0% |

| Maringá/PR | 109 | 83.8% |

| Paranã/TO | 122 | 92.0% |

| São Gonçalo/PB | 111 | 85.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva, J.C.C.M.; Paulino, T.F.; Machado, L.; Duarte, W.M. Study of the Maximum Pressures in an Evaporator of a Direct Expansion Heat Pump Using R744 Assisted by Solar Energy. Processes 2026, 14, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010103

Silva JCCM, Paulino TF, Machado L, Duarte WM. Study of the Maximum Pressures in an Evaporator of a Direct Expansion Heat Pump Using R744 Assisted by Solar Energy. Processes. 2026; 14(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Jéssica C. C. M., Tiago F. Paulino, Luiz Machado, and Willian M. Duarte. 2026. "Study of the Maximum Pressures in an Evaporator of a Direct Expansion Heat Pump Using R744 Assisted by Solar Energy" Processes 14, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010103

APA StyleSilva, J. C. C. M., Paulino, T. F., Machado, L., & Duarte, W. M. (2026). Study of the Maximum Pressures in an Evaporator of a Direct Expansion Heat Pump Using R744 Assisted by Solar Energy. Processes, 14(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010103