MILP-Based Multistage Co-Planning of Generation–Network–Storage in Rural Distribution Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A battery energy storage lifetime model is incorporated into the planning framework, which captures the impact of degradation on long-term decision-making;

- (2)

- The proposed multi-stage expansion planning framework realizes the coordinated optimization of substation construction or replacement, feeder construction or replacement, and new energy storage deployment, thereby effectively promoting the integrated development of generation, grid, and storage.

2. Multi-Stage Coordinated Expansion Planning Model for Rural Distribution Systems

2.1. Objective Function and Cost-Related Terms

2.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Investment Cost Constraints

- (2)

- Investment Status Constraints

- (3)

- Power Flow Constraints of the Distribution Network

- The per-unit voltage drop across each branch is equal to the difference in voltage magnitudes at the two end nodes of that branch.

- (4)

- Feeder-Related Constraints

- (5)

- Transformer-Related Constraints

- (6)

- Distributed Generator-Related Constraints

- (7)

- Energy Storage System (ESS) Constraints

- (8)

- Radial and Connectivity Constraints

- (9)

- Agricultural greenhouse Load

3. Solution Strategy

4. Case Study

4.1. Parameter Settings

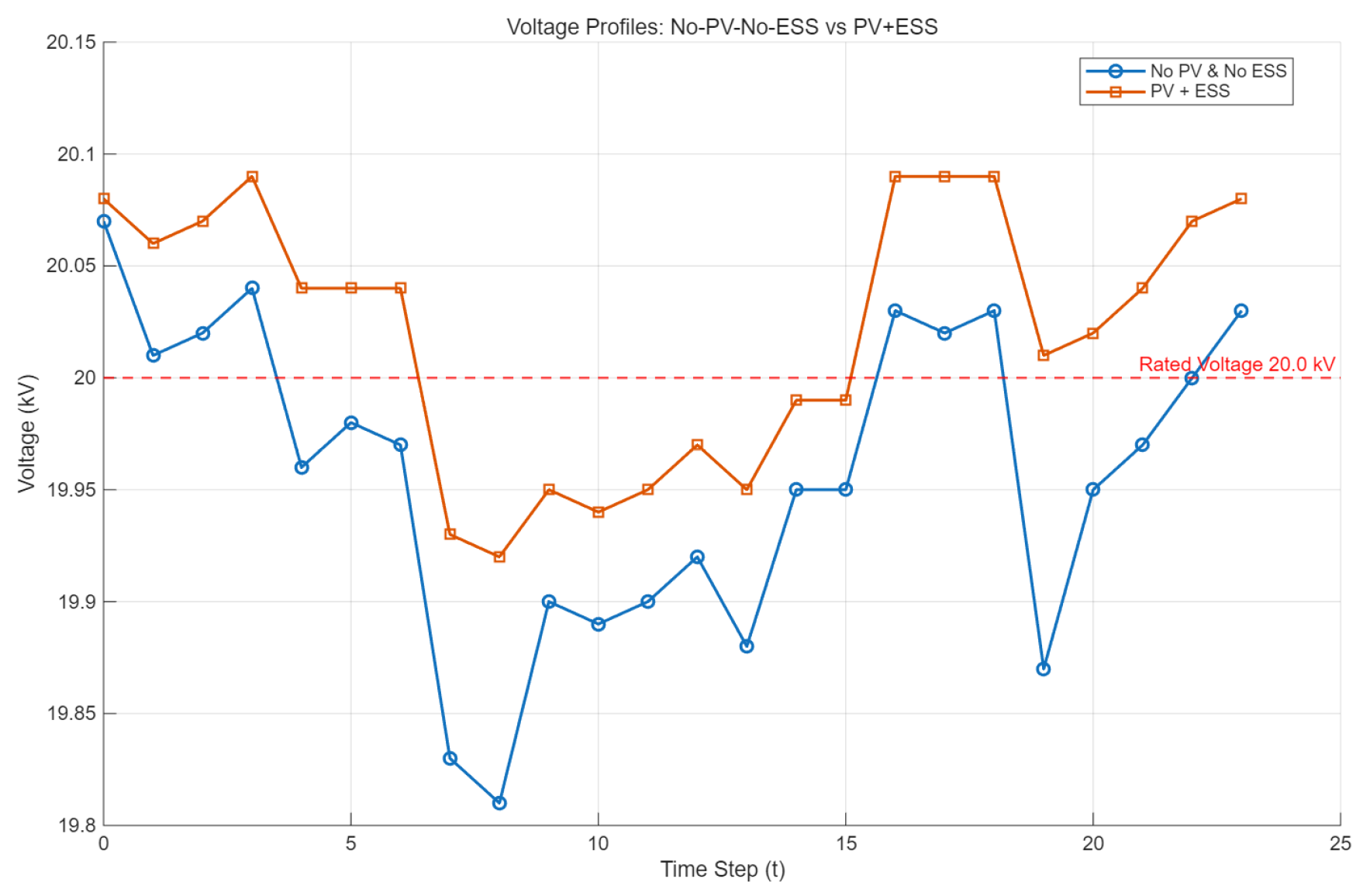

4.2. Results and Analysis

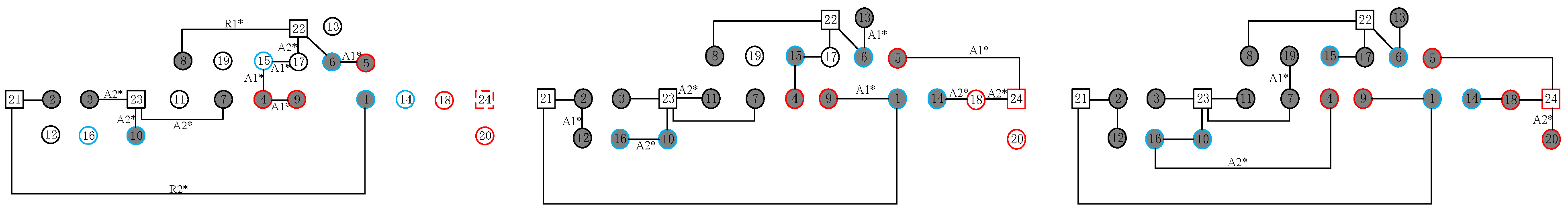

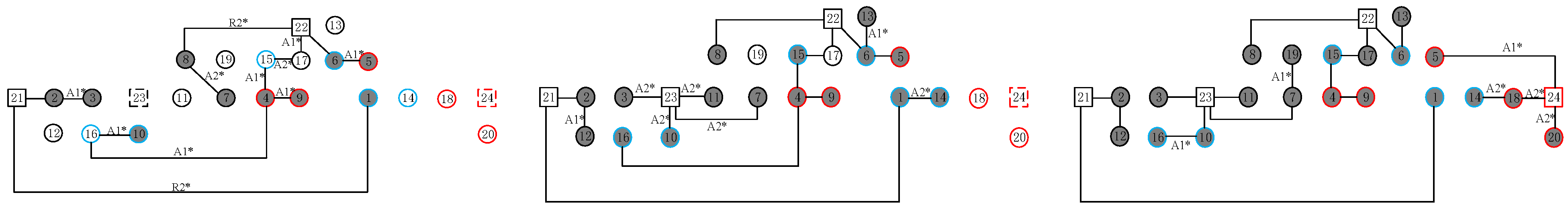

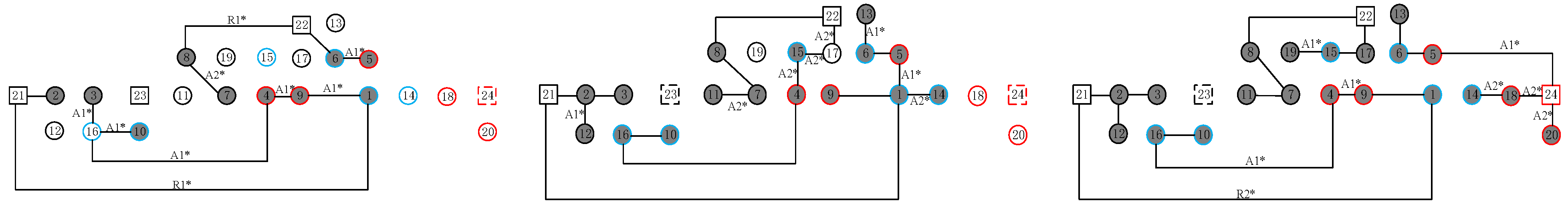

4.2.1. Analysis of Planning Schemes

4.2.2. Economic Comparison of Planning Schemes

4.2.3. Effect of Lifetime Constraints on Energy Storage Planning Schemes

- Case 1 (With lifetime model): the equivalent cycle constraint is considered in the optimization model, limiting the depth and frequency of charge–discharge cycles to reflect degradation effects on dispatch behavior.

- Case 2 (Without lifetime model): the equivalent cycle constraint is not considered in the optimization model, allowing unrestricted cycling during operation.

4.2.4. Sensitivity Analysis of PV Output and ESS Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A. Indices | |

| b | Typical day index. |

| k, κ | Indices for investment alternatives. |

| l | Feeder type index. |

| p | Generator type index. |

| r, s | Node indices. |

| y, τ | Time stage indices. |

| tr | Transformer type index. |

| v | Piecewise index for linearization of operating. |

| t | Index of time intervals within a day. |

| B. Set | |

| B | Set of typical days. |

| Set of candidate investment schemes for feeders, photovoltaic generators, and transformers. | |

| L | Set of feeder types, denoted as L = {EFF, ERF, NRF, NAF}, where EFF: existing fixed feeder, ERF: existing replaceable feeder, NRF: new replacement feeder, NAF: new added feeder. |

| P | Set of generator types, denoted as P = {PV}, where PV: photovoltaic generation. |

| Y | Set of planning stages. |

| T | Set of time intervals within a day. |

| TR | Set of transformer types, denoted as TR = {ET, NT}, where ET: existing trans-former, NT: new transformer. |

| Set of branches corresponding to feeder type l. | |

| Sets of nodes connected to node by a feeder of type, load nodes, system nodes, candidate nodes for distributed generation, and substation nodes, candidate nodes for energy storage system installation. | |

| C. Parameters | |

| Width of segment ν in piecewise linearization of operating for feeder/transformer. | |

| Unit energy cost of PV, substation, ESS; penalty cost of curtailed PV cost. | |

| Investment cost of feeder, transformer, PV, substation, ESS. | |

| Maintenance cost coefficients of feeders, generators, and transformers. | |

| Actual nodal peak demand and fictitious nodal demand. | |

| Feeder current limit. | |

| Rated and available PV capacity. | |

| Transformer current limit. | |

| ESS charge/discharge current limit. | |

| H, M | Sufficiently large constant. |

| i | Discount rate. |

| IBy | Budget in stage y. |

| kp | Fitting parameter of the relationship curve between the charge–discharge cycles of the energy storage system and the depth of discharge. |

| Length of feeder from node s to node r. | |

| Loss slope in segment ν of feeder/transformer. | |

| Maximum equivalent full cycles of the energy storage system over the planning horizon. | |

| Number of time stages, and loss segments. | |

| Illumination intensity in the greenhouse at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| Minimum daily light intensity received by crops per unit area in the greenhouse at node s, day b, year y. | |

| pf | Power factor. |

| Capital recovery rates for investment in feeders, new transformers, generators, and substations and ESS. | |

| Minimum and maximum state of charge of the energy storage system. | |

| Operating range of the supplemental lighting in the greenhouse at node s. | |

| Operating time of the supplemental lighting in the greenhouse at node s. | |

| Demand temperature for activating the shading net and the forced temperature for greenhouse node s. | |

| Lower and upper bounds for nodal voltages. | |

| Unit resistance of feeder k and transformer k. | |

| Lifetime of feeder, new transformer, PV unit, substation, and ESS, respectively. | |

| Charging and discharging efficiency of energy storage system. | |

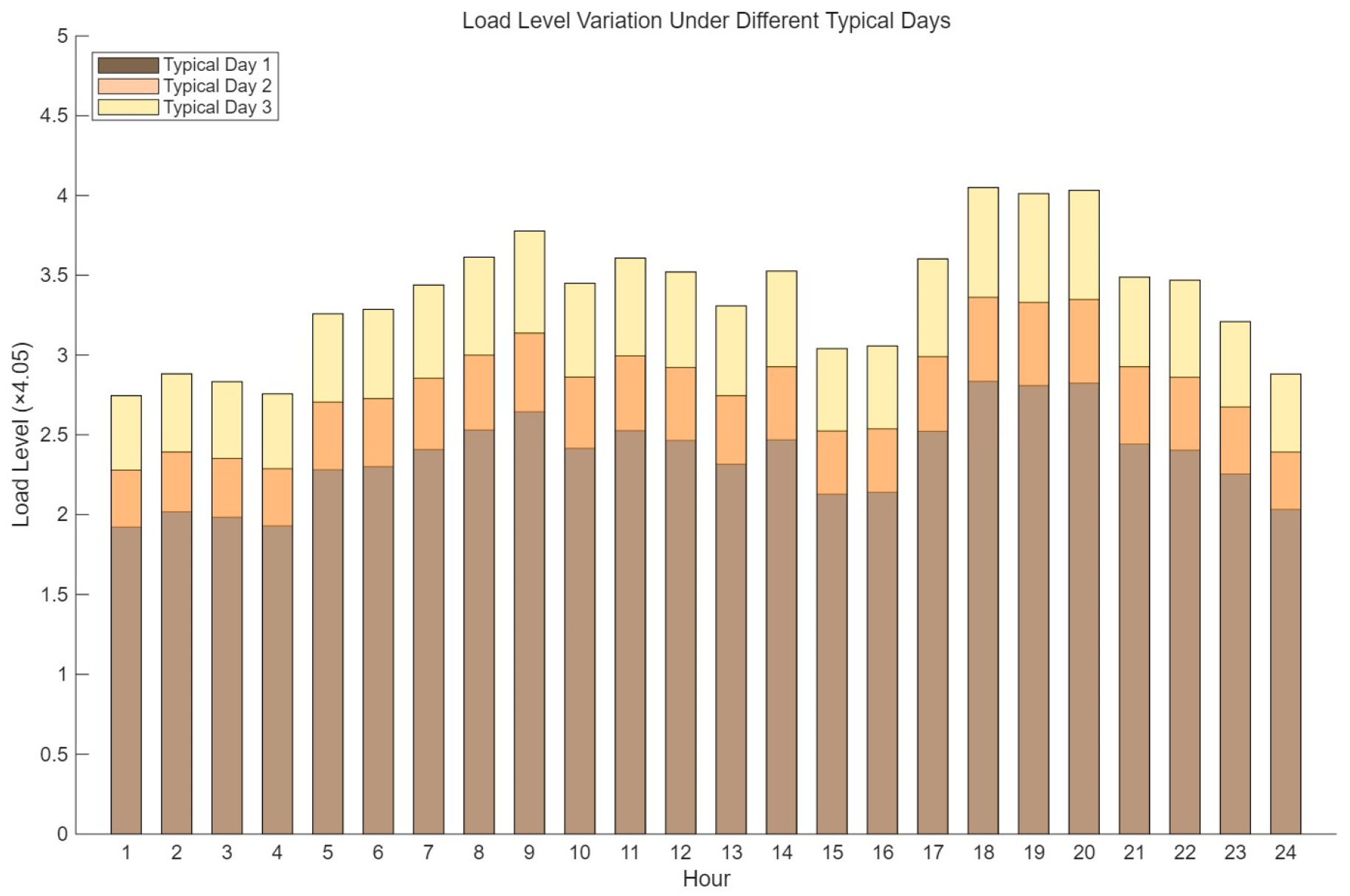

| Load factor of typical day b at time t. | |

| Upper limit of distributed generation penetration. | |

| Duration of each time step. | |

| D. Variables | |

| Unit production, maintenance, operating cost in year y. | |

| Investment cost in year y. | |

| Present value of total cost. | |

| Actual depth of discharge of the energy storage system at node s, year y, day b, time t. | |

| Boolean variables representing the operational status of the ventilation fan, water pump, motor, and supplemental lighting at node s, year y, day b, time t. | |

| Equivalent full cycles of the energy storage system at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| Actual and virtual current on feeder l from s to r. | |

| Power injected by PV, transformer, and virtual substation at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| Charging and discharging power of ESS at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| PV curtailment at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| Electricity demand of the greenhouse at node s, year y, day b, time t. | |

| Rated power of the water pump, ventilation fan, supple-mental lighting and motor at node s, year y, day b, time t. | |

| Tate of charge of the energy storage at node s, year y, day b, time t. | |

| Binary variable for virtual switch z on line from node s to r, feeder l, year k. | |

| Voltage magnitude at node s, time t, day b, year y. | |

| Binary investment variables for feeder, new transformer, PV, substation, and ESS at node s, year y. | |

| Binary operation state of feeder, PV, and transformer, respectively. | |

| Binary charging and discharging state of ESS at node s. | |

| Current in segment ν for piecewise operating of feeder and transformer. | |

| Abbreviations | |

| DG | Distributed Generation. |

| PV | Photovoltaic. |

| ESS | Energy Storage System. |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming. |

| MINLP | Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming. |

References

- Afraz, A.; Rezaeealam, B.; Seyedshenava, S.; Doostizadeh, M. Active Distribution Network Planning Considering Shared Demand Management. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 37, 8015–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, M.; Ghassemi, M. Optimal Planning of Microgrids for Resilient Distribution Networks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 128, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wei, C.; Wang, J.; Liao, S.; Ke, D.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Peng, X. Coordinated Operation of Gas-Electricity Integrated Distribution System With Multi-CCHP and Distributed Renewable Energy Sources. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jin, Y.; You, F. Active Disturbance Rejection Temperature Control of Open-Cathode Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, G.; You, F. Combined Internal Resistance and State-of-Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery Based on Extended State Observer. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 109994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, H.; Mahmud, F.F. Integrated Planning for Distribution Automation and Network Capacity Expansion. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 4279–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoukis, N.; Georgilakis, P. A Chance-Constrained Multistage Planning Method for Active Distribution Networks. Energies 2019, 12, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, W.R.; Martins, D.B.; Nametala, C.A.L.; Pereira, B.R. Protection System Planning for Distribution Networks: A Probabilistic Approach. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2020, 189, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delarestaghi, J.M.; Arefi, A.; Ledwich, G.; Borghetti, A. A Distribution Network Planning Model Considering Neighborhood Energy Trading. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 191, 106894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedzadeh, S.; Ravadanegh, S.N.; Haghifam, M.R. Microgrid-Based Resilient Distribution Network Planning for a New Town. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2021, 15, 3524–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Chen, J.; Xi, M.; Tao, Y.; Deng, Z. Multi-Objective Planning of Distributed Photovoltaic Power Generation Based on Multi-Attribute Decision Making Theory. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 223021–223029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawon, S.M.R.H.; Liang, X.; Janbakhsh, M. Optimal Placement of Distributed Generation Units for Microgrid Planning in Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 2785–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Wei, B.; Dongyang, Q. Locating and Sizing Planning of Distributed Generation Power Supply Considering the Operational Risk Cost of Distribution Network. Trans. China Electrotech. Soc. 2019, 34, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooshaki, M.; Farzin, H.; Abbaspour, A.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Lehtonen, M. A Model for Stochastic Planning of Distribution Network and Autonomous DG Units. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020, 16, 3685–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, T.; Moghaddam, S.Z. Coordinated Scheme for Expansion Planning of Distribution Networks: A Bilevel Game Approach. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2020, 14, 2839–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Delgado, G. Joint Expansion Planning of Distributed Generation and Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 30, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Pourghaderi, N.; Dehghanian, P. A Bi-Level Framework for Expansion Planning in Active Power Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 2639–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yuan, X.; Gao, H.; Ma, J.; Chen, Z. FFRLS-Based Data-Driven Voltage Security Assessment for Active Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 5685–5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemin, D.; Yueming, L.; Zhicheng, Y.; Youhong, Y.; Yongbao, L. Coordinated control strategy of engine-grid-load-storage for shipboard micro gas turbine DC power generation system: A review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 134, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni-Bonab, S.M.; Kamwa, I.; Moeini, A.; Rabiee, A. Voltage Security-Constrained Stochastic Programming Model for Day-Ahead BESS Scheduling in Co-Optimization of Transmission & Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain Energy 2020, 11, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apribowo, C.H.B.; Sarjiya, S.; Hadi, S.P.; Wijaya, F.D. Optimal planning of battery energy storage systems by considering battery degradation due to ambient temperature: A review, challenges, and new perspective. Batteries 2022, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, G.; Brouhard, T.; DeForest, N.; Wang, D.; Heleno, M.; Kotzur, L. Battery aging in multi-energy microgrid design using mixed integer linear programming. Appl. Energy. 2018, 231, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooshaki, M.; Abbaspour, A.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Farzin, H.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Lehtonen, M. A MILP Model for Incorporating Reliability Indices in Distribution System Expansion Planning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 2453–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooshaki, M.; Abbaspour, A.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Lehtonen, M. MILP Model of Electricity Distribution Sys-tem Expansion Planning Considering Incentive Reliability Regulations. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 4300–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirifar, M.; Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M.; Moeini-Aghtaie, M.; Pourghaderi, N. Joint Distributed Generation and Active Distribution Network Expansion Planning Considering Active Management of Network. In Proceedings of the 27th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Yazd, Iran, 30 April–2 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotero, R.C.; Contreras, J. Distribution System Planning With Reliability. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2011, 26, 2552–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khattam, W.; Hegazy, Y.G.; Salama, M.M.A. An Integrated Distributed Generation Optimization Model for Distribution System Planning. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2005, 20, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, E.; Seifi, H.; Sepasian, M.S. A Dynamic Approach for Distribution System Planning Considering Dis-tributed Generation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2012, 27, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, M.E.; Vargas, A. Investment Decisions in Distribution Networks Under Uncertainty With Distributed Generation—Part I: Model Formulation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 2331–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, M.E.; Vargas, A. Investment Decisions in Distribution Networks Under Uncertainty With Distributed Generation—Part II: Implementation and Results. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IBM ILOG CPLEX Website. 2014. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/cn-zh/products/ilog-cplex-optimization-studio (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Nemhauser, G.; Wolsey, L. Integer and Combinatorial Optimization; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zones | Load Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| A | 400 | 700 | 900 |

| B | 350 | 600 | 850 |

| C | 300 | 500 | 800 |

| Line | Length (km) | Line | Length (km) | Line | Length | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | r | s | r | s | r | |||

| 1 | 5 | 2.67 | 4 | 9 | 1.20 | 7 | 23 | 0.90 |

| 1 | 9 | 1.27 | 4 | 15 | 1.60 | 8 | 22 | 1.90 |

| 1 | 14 | 1.27 | 4 | 16 | 1.30 | 10 | 16 | 1.60 |

| 1 | 21 | 2.67 | 5 | 6 | 2.40 | 10 | 23 | 1.30 |

| 2 | 3 | 2.00 | 5 | 24 | 0.70 | 11 | 23 | 1.60 |

| 2 | 12 | 1.10 | 6 | 13 | 1.20 | 14 | 18 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 21 | 1.70 | 6 | 17 | 2.20 | 15 | 17 | 1.20 |

| 3 | 10 | 1.10 | 6 | 22 | 2.70 | 15 | 19 | 0.80 |

| 3 | 16 | 1.20 | 7 | 8 | 2.00 | 17 | 22 | 1.50 |

| 3 | 23 | 1.20 | 7 | 11 | 1.10 | 18 | 24 | 1.50 |

| 4 | 7 | 2.60 | 7 | 19 | 1.20 | 20 | 24 | 0.90 |

| Types | NRF | NAF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candidate 1 | (MVA) | 6.29 | 3.98 |

| (Ω/km) | 0.557 | 0.734 | |

| ($/km) | 19,140 | 15,020 | |

| Candidate 2 | (MVA) | 9.23 | 6.33 |

| (Ω/km) | 0.458 | 0.557 | |

| ($/km) | 29,870 | 25,030 | |

| Replacement Option 1 | (MVA) | 12 |

| (Ω) | 0.16 | |

| ($) | 2000 | |

| ($) | 750,000 | |

| Replacement Option 2 | (MVA) | 15 |

| (Ω) | 0.13 | |

| ($) | 3000 | |

| ($) | 950,000 |

| ($) | ($/MWh) | (MVA) | (MW) | (MW) |

| 150,000 | 180 | 50 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Scheme | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No PV, No ESS | — | — | — | — |

| PV Only | Installation Node | PV: 9, 4 | PV: 1, 9, 4, 17 | PV: 1, 7, 9, 15, 18, 4, 17 |

| Installed Capacity | 8.10 MWh | 16.20 MWh | 28.35 MWh | |

| PV + ESS | Installation Node | PV: 3, 9, 4 ESS: 1, 5, 9, 16 | PV: 1, 3, 9, 4, 5 ESS: 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, 13, 15, 16 | PV: 1, 3, 9, 15, 16, 18, 4, 5 ESS: 1, 3, 4, 5, 9, 13, 15, 16, 18, 20 |

| Installed Capacity | PV: 12.15 MWh ESS: 6.00 MWh | PV: 20.25 MWh ESS: 12.00 MWh | PV: 28.35 MWh ESS: 13.50 MWh | |

| Investment Cost | Maintenance Cost | Generation Cost | Operating Cost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No PV, No ESS | Stage 1 | 0.1230 | 0.0094 | 8.9088 | 0.1576 |

| Stage 2 | 0.1136 | 0.0141 | 14.7659 | 0.2960 | |

| Stage 3 | 0.0046 | 0.0150 | 25.0827 | 0.5729 | |

| PV Only | Stage 1 | 0.3920 | 0.0766 | 8.1593 | 0.0708 |

| Stage 2 | 0.4457 | 0.2021 | 13.1885 | 0.1474 | |

| Stage 3 | 0.4747 | 0.3785 | 22.0204 | 0.2647 | |

| PV + ESS | Stage 1 | 0.6293 | 0.2581 | 7.1162 | 0.1424 |

| Stage 2 | 0.4871 | 0.4326 | 11.7879 | 0.1849 | |

| Stage 3 | 0.4342 | 0.5554 | 20.7891 | 0.2761 |

| Cost Component | No PV, No ESS | PV Only | PV + ESS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment Cost | 3.0652 | 16.0713 | 19.2337 |

| Maintenance Cost | 0.2053 | 4.8949 | 7.4375 |

| Generation Cost | 329.1814 | 289.5051 | 272.1906 |

| Operating Cost | 7.4394 | 3.4452 | 3.6841 |

| 339.894 | 313.9165 | 302.5459 |

| Case | PV Accommodation Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Without ESS | 83.5 |

| With ESS | 92.8 |

| Case | Average SOC | Total Cost (106 $) |

|---|---|---|

| Without lifetime model | 0.74 | 303.4059 |

| With lifetime model | 0.82 | 302.5459 |

| Changes in PV Generation and ESS Capacity | Total Cost (106 $) | |

|---|---|---|

| PV | ESS | |

| −10% | 0% | 305.5037 |

| 0% | 0% | 302.5459 |

| +10% | 0% | 298.4785 |

| 0% | −10% | 304.8923 |

| 0% | +0% | 302.5459 |

| 0% | +10% | 301.3278 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Shi, T.; Jiao, F.; Xu, J. MILP-Based Multistage Co-Planning of Generation–Network–Storage in Rural Distribution Systems. Processes 2025, 13, 3859. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123859

Yang X, Zhu L, Wang X, Zhou F, Shi T, Jiao F, Xu J. MILP-Based Multistage Co-Planning of Generation–Network–Storage in Rural Distribution Systems. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3859. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123859

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xin, Liuzhu Zhu, Xuli Wang, Fan Zhou, Tiancheng Shi, Fei Jiao, and Jun Xu. 2025. "MILP-Based Multistage Co-Planning of Generation–Network–Storage in Rural Distribution Systems" Processes 13, no. 12: 3859. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123859

APA StyleYang, X., Zhu, L., Wang, X., Zhou, F., Shi, T., Jiao, F., & Xu, J. (2025). MILP-Based Multistage Co-Planning of Generation–Network–Storage in Rural Distribution Systems. Processes, 13(12), 3859. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123859