1. Introduction

In sectors in which electrification is technically or economically demanding, one of the key means of achieving decarbonisation is hydrogen management. The European Union has established a goal to create a functional renewable hydrogen market (Hydrogen Strategy for a Climate Neutral Europe) [

1]. This goal also includes the construction of an extensive network of hydrogen refuelling stations along key transport corridors; according to the Regulation (EU) 2023/1804 AFIR, a public hydrogen refuelling station must be available every 200 km of main roads in the EU [

2]. Another part of the goal is to support the production of green hydrogen from renewable energy sources, build a hydrogen infrastructure, create storage capacities, and establish the use of fuel cells in heavy-duty vehicles and buses, as well as in rail, sea and air transport sectors [

3]. According to the REPowerEU Report, in the EU, 20 million tonnes of hydrogen produced from renewable sources should be consumed by 2030, while approximately half of that amount should be imported [

4].

In order to accomplish these objectives, various support mechanisms and programmes have been developed (Horizon Europe, Innovation Fund, Connecting Europe Facility, and Fit for 55) to fund hydrogen technology development. The EU’s long-term vision is the complete integration of hydrogen into its transport system by 2050, contributing to climate neutrality. This framework constitutes a legislative and investment- and innovation-related basis for developing hydrogen mobility across Europe [

4,

5].

Hydrogen technologies are currently used in multiple applications, ranging from small portable equipment up to large industrial applications and energy systems. In the transport sector, they constitute a possible alternative to conventional fossil fuels and can supplement electromobility based on battery systems [

6].

Hydrogen storage tank safety is crucial for their extensive use in energy applications and in the transport sector. Their wall material is one of the key factors determining the potential applications of tanks in industry. Through metal materials such as steel or aluminium, hydrogen leakage is very low. In metals, atomic hydrogen is subjected to diffusion; H

2 molecules on the tank’s surface dissociate into atoms, which are then diffused through the crystalline lattice and then recombined on the opposite side. The permeability of polymers is a thousand- or even million-fold higher than that of steel [

7,

8]. The main risk associated with metal tank use is therefore not leakage but hydrogen embrittlement, i.e., degraded strength caused by atomic hydrogen diffusion.

In addition to the commonly used hydrogen tanks, such as Types I and III (fully metal tanks, those that are hoop-wrapped with fibre-reinforced composite, and those that are fully wrapped), intensive development is also caried out with Types IV and V (polymer liners fully wrapped with carbon fibre composite, and no liners which are entirely composite with a gas-tight resin matrix) [

9,

10]. According to the scientific literature [

11], polyamides and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) exhibit excellent hydrogen barrier properties. The study also examined the effects of adding nanomaterials such as graphene and montmorillonite clay. As for Type IV tanks, an important factor is the production method, including its temperature and pressure, which affect the structure of the material, and hence its permeability. The optimisation of these processes is crucial for achieving low permeation.

Chemical forms of storage, including those involving metal hydrides (MHs), constitute an attractive alternative due to their hydrogen binding ability at low pressures. Hydrogen absorption into MH alloys is exothermic; heat released during hydrogen storage must be effectively removed to avoid tank overheating. On the other hand, the desorption process is endothermic and requires that heat is supplied back to avoid flow rate and pressure drops [

12]. Effective hydrogen release is achievable with the use of multiple commercial MH alloys at temperatures of up to 60 °C, which may also be easily provided through the secondary use of waste heat. An important trend observed in this field is the use of the waste heat from fuel cells to support hydrogen desorption [

13]. In terms of the wide-spectrum commercialisation of hydrogen storage systems in metal alloys, designing an efficient thermal management system for MH tanks is one of the greatest challenges [

14,

15]. Research indicates that when such a system is correctly designed, as much as 20% of the waste heat from a fuel cell may be used for heating a MH tank; this significantly improves hydrogen supply continuity and increases the reliability of the whole system [

13].

Metal hydride tanks exhibit a high volumetric density and safety; as such, they are intended for stationary and mobile applications, in which safety is one of the most crucial criteria [

16,

17]. In recent years, various designs have been examined, ranging from the integration of internal ribs and fins, through the use of materials with high thermal conductivity, to the integration of cooling and heating circuits that create optimal hydrogen absorption and desorption conditions [

6].

In order to create an optimal tank design, the processes that run in a metal hydride storage tank must be modelled. Numerical simulations that use finite volume or element methods facilitate detailed analysis of heat and matter transport, as well as the identification of critical tank regions [

18]. Analytical models, albeit simplified, provide a valuable tool for the fast estimation of dynamic characteristics such as the time constant, which is fundamental to designing control algorithms [

19].

In certain countries, hydrogen storage systems based on metal hydrides are now being used in multiple practical applications [

20,

21]. In Japan and Europe, they have been tested for use in buses and other means of public transport, as a safe alternative to high-pressure storage tanks [

22]. Compared to the high-pressure Type III, IV, and V tanks, the use of MH tanks for hydrogen storage is primarily beneficial in terms of safety. Low pressures mitigate leakage risks. If a tank suddenly ruptures, hydrogen is released from the hydride structure over a longer time interval, due to the slower kinetics compared to those observed in high-pressure tank ruptures. A metal hydride storage tank facilitates long-term hydrogen storage without losses, except for the negligible amount of hydrogen diffused through the tank’s material (316L stainless steel). Moreover, MH materials facilitate long-term hydrogen storage without the need for external cooling, as is the case with adsorption-based storage in MOF materials.

The latest advancements and trends in material technologies, detection systems, and smart monitoring contribute to mitigating the risks associated with the use of various hydrogen storage systems. Further research and development in this field is required in order to ensure the safe and efficient use of hydrogen as a clean energy source [

11]. The most limiting parameter of MH storage tanks is their higher mass compared to that of high-pressure vessels, as well as the hydrogen release kinetics.

In China, the integration of expanded natural graphite or metal foams into the hydride bed is currently being intensively investigated, demonstrating significant absorption time reductions [

23]. In the USA, metal hydrides are being investigated not only in transport applications, but also in stationary applications [

24]. In addition, new types of hydrides, including high-entropy hydrides, are being developed all over the world, facilitating the fast and reversible storage of hydrogen at relatively low temperatures and pressures [

25].

Based on the aforementioned trends, this paper deals with the interconnecting experimental measurements, numerical simulations and analytical modelling of a MNTZV-159 metal hydride tank designed and homologised at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Technical University of Košice. The goal was to validate computational approaches with real-life data, identify the tank time constant, and analyse the potential practical applications of these systems in hydrogen-powered passenger cars and agricultural vehicles.

The certified storage tank used in the experiment did not contain any internal temperature sensors; therefore, the thermal field inside the tank could only be identified using numerical calculations focusing on CFD analysis of the heat flow and transport using the boundary conditions identified in the hydrogen desorption experiment. The calculation facilitated analysing the thermal field and defining the average tank temperature as a function of time.

The purpose of the article was to identify the tank time constant, which must be known in order to ensure that the MH storage tank installed in the transport vehicle functions properly. For that purpose, an analytical calculation was created to identify the average tank temperature as a function of time. This calculation facilitates the practical identification of MH storage parameters, without the need for long numerical calculations.

2. Description of the Storage System’s Integration into a Vehicle

A low-pressure hydrogen storage system based on the use of metal hydrides with a storage capacity of 5 kg of H

2 was implemented in a transport vehicle (FIRST FCLEI 80, Rošero-P, Spišská Nová Ves, Slovakia) with a purely electric motor. For the purpose of hydrogen storage, MNTZV-159 metal hydride (MH) hydrogen storage tanks were designed, produced and certified. They incorporated an internal and external heat exchanger. Each MNTZV-159 tank contained 47 kg of Hydralloy C5. The tank’s operating and structural parameters are listed in

Table 1.

Six tanks were installed in the transport vehicle in order to facilitate a hydrogen-powered range of 150 km. Inside the tanks, hydrogen was chemically bound in the alloy, while the reaction heat released during absorption amounted to Δ

H(abs) = 22.69 kJ·mol

−1, i.e., 1.01 MJ·m

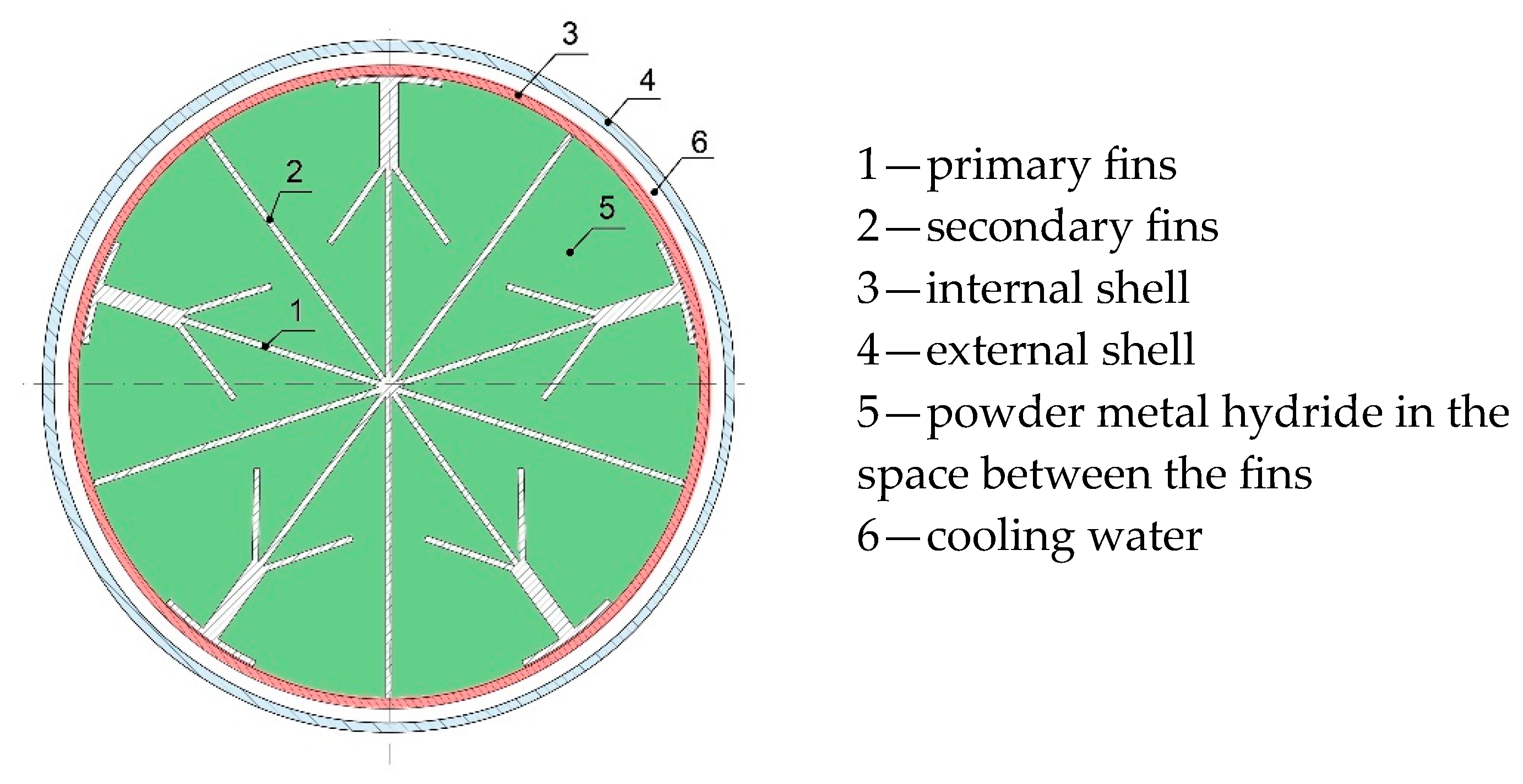

−3. In order to achieve pressure equilibrium during refuelling, the tank was cooled with a cooling circuit that removed heat from its surface. Heat transport from the tank’s core was maximised, and the effective thermal conductivity of the metal hydride increased, by implementing internal ribs with primary and secondary fins (

Figure 1).

Without ribs, the thermal conductivity of the MH was as low as 1 W·m

−1·K

−1; such a low value did not facilitate fast absorption across the entire tank and impaired desorption kinetics. During refuelling, heat was transported from the tank core onto the 316L steel shell through aluminium ribs and was then removed by water circulating through the air cooler (

Figure 2).

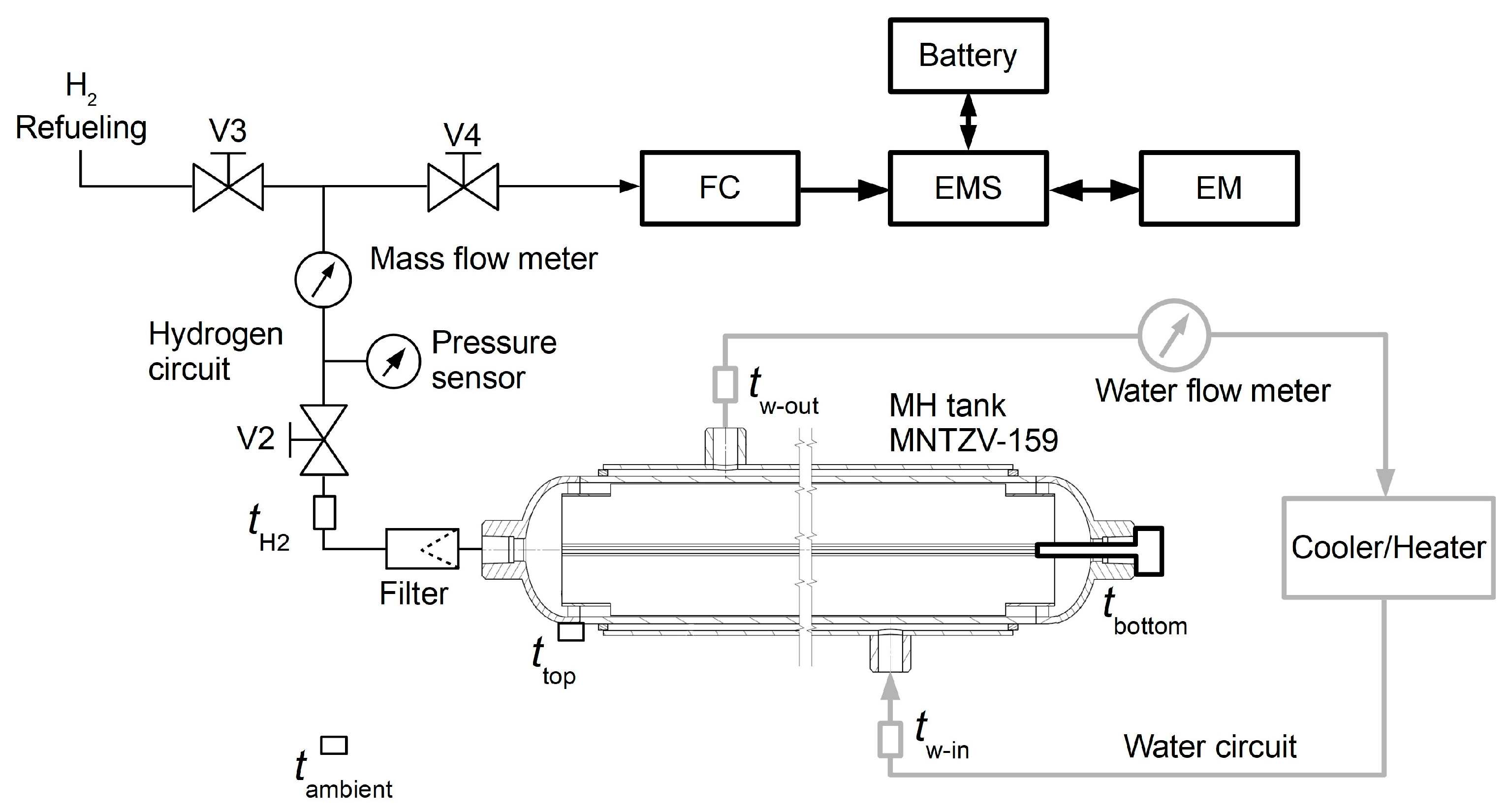

Hydrogen refuelling was carried out as follows:

Launching the cooler and the circulation of the cooling fluid;

Connecting the hydrogen source with a pressure of 3 MPa;

Opening the V2 and V3 valves to facilitate hydrogen flow into the MNTZV159 tank through the Bronkhorst IN-FLOW flow meter, F-113AI-M50-ABD-HH-V-0C series (D-Ex Instruments, Bratislava, Slovakia);

After the tank was filled with the required volume, the branch was closed using the V3 valve.

The system included an ATEX relative pressure sensor—BD Sensor DX10-DMP 333l NG (range of 0–60 bar) (BD Senzors, Buchlovice, Czech Republic). The temperature was monitored using NTCC-10K temperature sensors (EPCOS, supplier: TME, Slovakia) in the MH tank and NTC B57301K0103A001 water temperature sensors (EPCOS, supplier: TME, Slovakia).

Hydrogen was used to power the transport vehicle as follows:

Heating the tank using a water circuit;

Opening the V4 valve to initiate hydrogen desorption, and a concurrent measurement of the hydrogen pressure and flow rate;

The fuel cell produced the electric energy for the actuating system.

During hydrogen desorption, it was necessary to supply heat at ΔH(abs) = 27.8 kJ·mol−1, i.e., 1.24 MJ·m−3. This was carried out by conducting heat from the fuel cell, where the total consumption of heat energy produced to release hydrogen amounted to a maximum of 20% (practical experience gained in operating the transport vehicle). Following filtration (and aiming to avoid fuel cell contamination with the metal powder), the hydrogen flow was again subjected to flow rate and pressure measurements. It was then chemically bound to air oxygen in the fuel cell with an electric power of 30 kW and an average efficiency of 50%. The input hydrogen pressure amounted to a minimum of 7 bar, while at pressures below that value, the fuel cell stopped running; supplying heat to the tanks was necessary in order to avoid such stoppage.

The electromotor’s (EM) input power was 100 kW and its peak short-term power was 150 kW. In order to ensure the required maximum power, the direct use of electric energy from the fuel cell was supplemented with energy from a 30 kWh battery, with a maximum peak power of 120 kW. The electric flows were managed using an EMS (Energy Management System) applying braking energy recuperation, which was stored in a battery for later use.

The fuel cell’s maximum peak hydrogen release was 7.2 L·s−1, i.e., 1.2 L·s−1 per MNTZV-159 tank. Achieving such a stable supply with the aforementioned flow rate was significantly problematic due to the pressure drops caused by the non-homogeneity of the thermal field and the need to maintain a sufficient heat supply across the entire tank. In order to identify the maximum hydrogen supply duration at maximum fuel cell performance, an experimental measurement was carried out on one of the tanks during simulated transport vehicle operation. In order to visualise the tank’s internal field and hence facilitate an analysis of the effect of the average absorption material temperature on hydrogen pressure and flow rate stability, a numerical simulation of the heat transport and flow in the tank during hydrogen desorption was carried out.

This experimental measurement was carried out using laboratory equipment arranged as shown in

Figure 2, without using the fuel cell and without consuming electric energy. Hydrogen release was simulated by reducing its flow into the atmosphere.

The MNTZV-159 tank was filled with hydrogen to a total volume of 5 m

3 and heated to a temperature of 52.3 °C using the external water circuit. This was the average operational temperature of the thermally insulated tank. The inlet water flow rate was regulated in order to maintain the value of 3.4 L·min

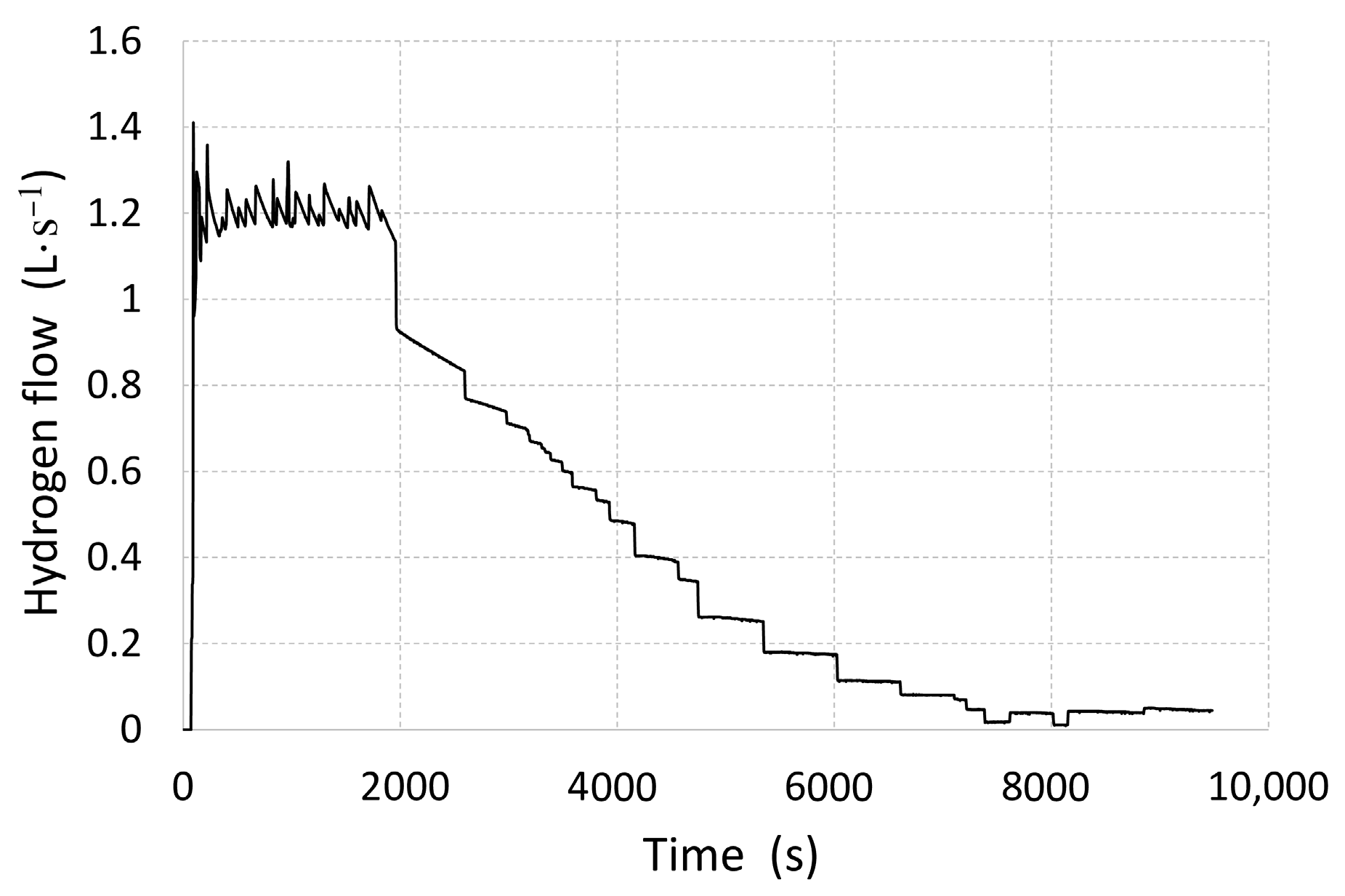

−1, representing the real projected flow rate for the vehicle when in use. The average water temperature at the inlet was 64.5 °C, which is the maximum temperature obtained from the fuel cell when in use. During the measurements, hydrogen release was simulated with a regulated value of 1.2 L·s

−1 for as long as 2000 s (

Figure 3), until the pressure in the tank reached 8 bar (

Figure 4). This was because at any lower pressure there would be a risk of the fuel cell stopping, due to other pressure losses that occur in the hydrogen distribution pipes and on their components.

In order to prevent further pressure drops below the minimum value, tank pressure was regulated to maintain 8 bar by gradually decreasing the hydrogen flow rate. Hydrogen desorption was discontinued after 9400 s, since it was no longer possible to maintain the required pressure despite the intensive tank heating.

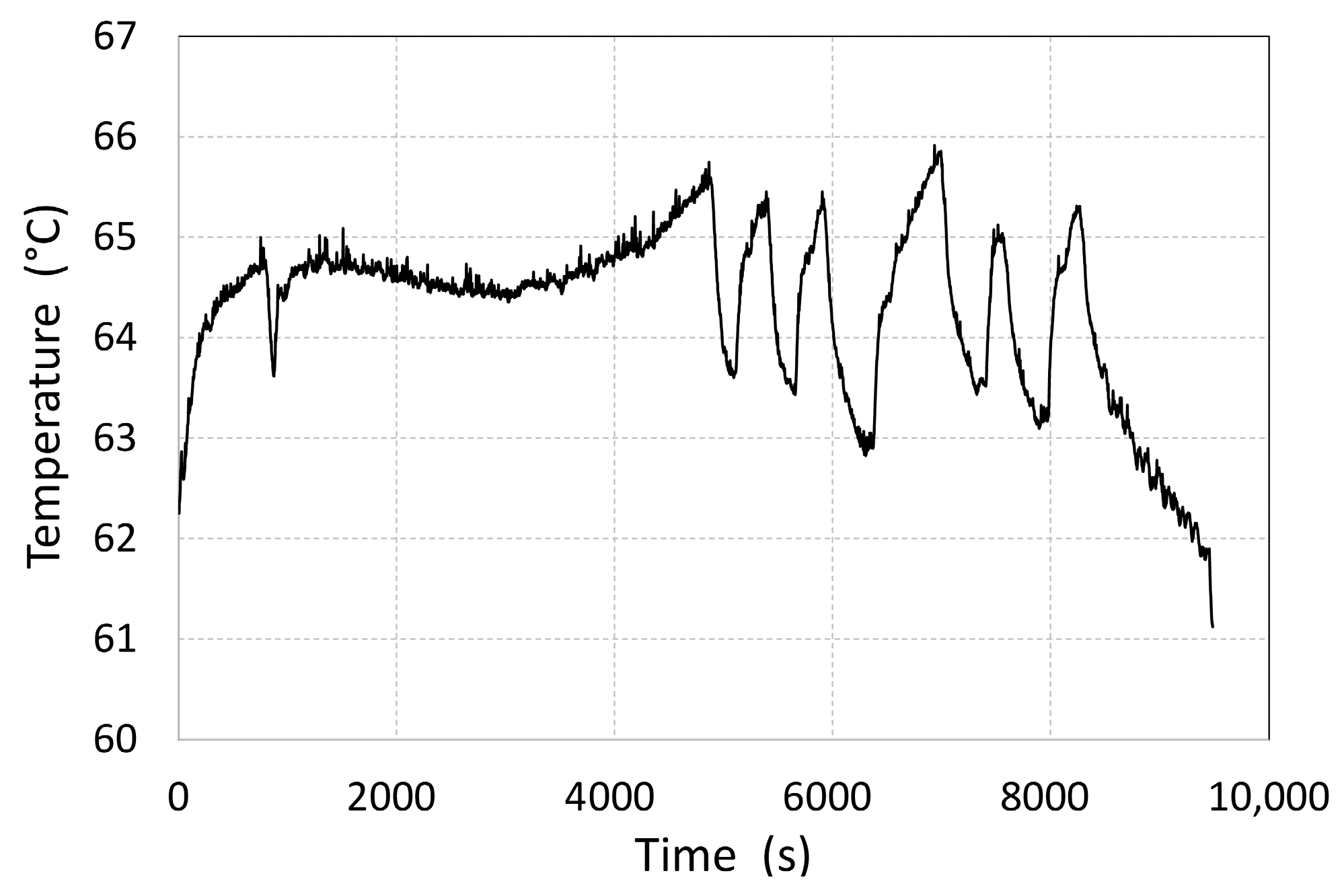

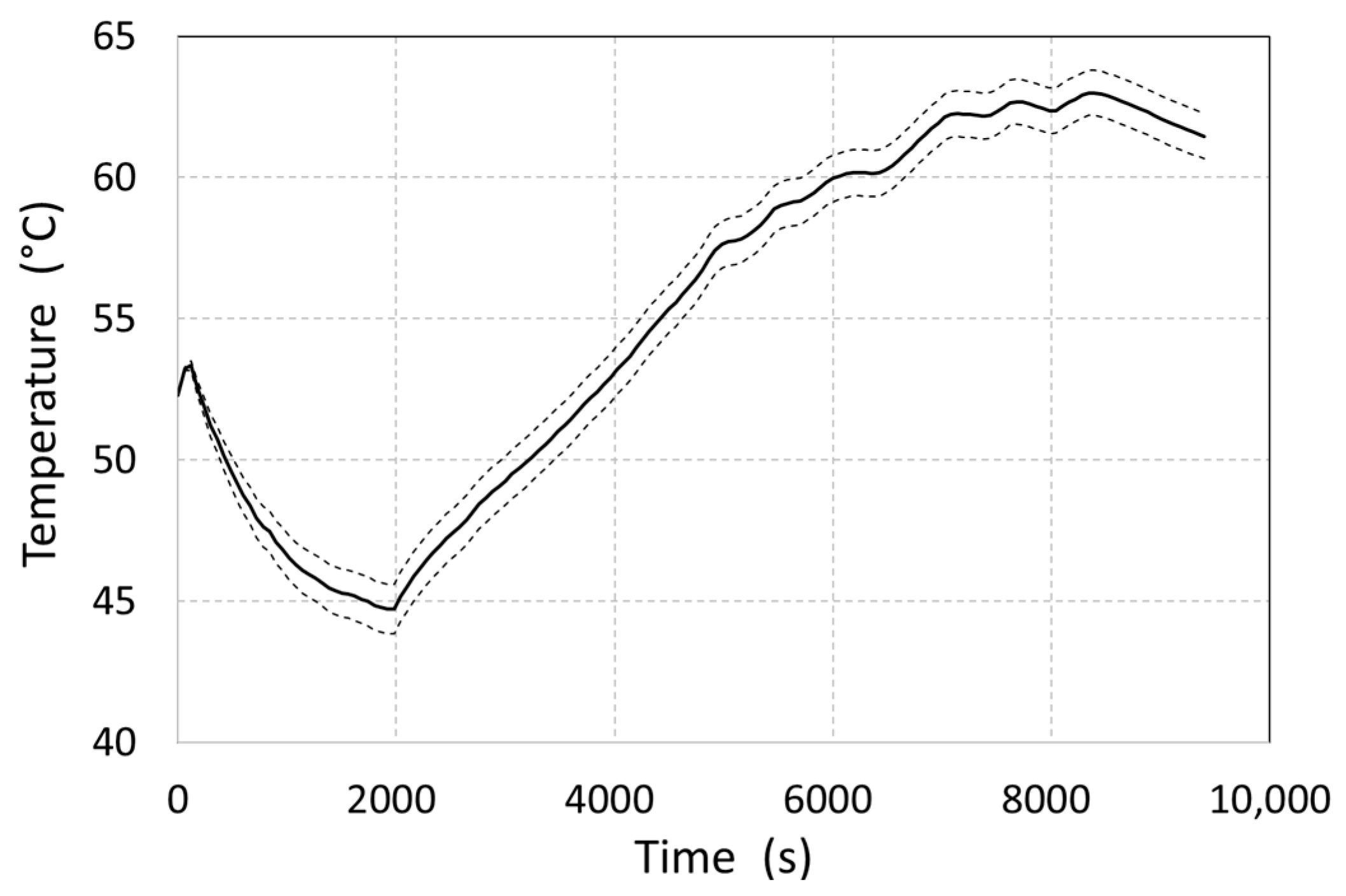

The cooling circulation system was thermally interconnected with the tank. Even though the temperature of the water entering the tank was regulated, sudden changes occurred in the flow rate and a change in the internal heat source resulted in temperature oscillations ranging from 62 to 66 °C. This phenomenon was observed in the time interval of 4000–8400 s (

Figure 5). Similar temperature oscillations are also common when the tank is directly filled from the fuel cell, since the heat-carrying fluid in real-life vehicle operation is separated from the cell by a plate heat exchanger. Changes in the temperature of the water leaving the tank also affect, with a certain delay, the inlet temperature of the heat-carrying fluid supply.

The tank’s shape and homologation did not facilitate measuring the thermal field inside. Using the boundary conditions identified in the experiment, a numerical calculation was thus conducted to identify the flow rate of the heat-carrying fluid and the heat transport during hydrogen desorption. For this, the measured values were used as the boundary and baseline conditions.

During its release from a tank, hydrogen pressure and temperature normally decrease. After hydrogen release stops, the temperature may be increased again by water in the heating circuit, which will also increase the pressure and, in addition, facilitate achieving an appropriate flow rate level for the fuel cell. Therefore, a simplified analytical calculation was conducted to identify the tank time constant necessary for adjusting the transport vehicle control system.

3. Numerical Calculation of the MH Tank’s Thermal Field

We numerically calculated the heat conduction and flow rate of the heat-carrying fluid for the MNTZV159 tank’s 3D geometry, aiming to identify the internal temperature distribution during desorption.

Heat transport in the metal hydride material and heat flow in the space between the shells was simulated in the CFX module of the ANSYS software 2024 R1 by applying the finite volume method [

26]. The goal was to identify the thermal field across the entire tank. The numerical simulation was based on the following hypotheses:

During absorption, hydrogen is released in the powder metal hydride through an even distribution of the thermal power;

A decrease in the pressure of hydrogen flowing through the powder metal hydride bed is not analysed, and homogeneous absorption in the entire volume of the metal hydride is assumed (the geometry of the internal ribs facilitates the flow of hydrogen outside the powder material, reaching the lower lid, which creates a more homogeneous pressure field along the tank);

The calculation does not analyse the plateau pressure defined by the Van’t Hoff law;

The calculation is conducted with constant solid material heat capacity and thermal conductivity values.

These hypotheses facilitated our calculation of the thermal field, with even heat generation across the entire volume of the MH material. In a real-life tank, desorption is faster in material grains heated to a higher temperature, forming a non-homogeneous concentration. In the experiment with a longer desorption time (2000 s), the concentration differences were neglected, as they were only minimal. Therefore, a homogeneous internal heat source was considered, identified based on the measured hydrogen flow rate and pressure values.

Calculations for the metal hydride’s heat transport, the internal aluminium ribs and the tank shell were carried out by applying the following heat diffusion equation [

27]:

wherein ∂

T/∂

τ is the change in temperature in the infinitesimal time interval (K·s

−1);

α is the thermal diffusivity of the material (m

2∙s

−1); ∇

T is the temperature gradient in the cartesian coordinate system (K∙m

−1);

qis is the thermal power generated or absorbed in a volume unit (W∙m

−3);

ρ is the specific gravity of the analysed material (kg∙m

−3); and

c is the heat capacity (J∙kg

−1∙K

−1).

Numerical analysis was carried out for the alloy with a maximum stored hydrogen concentration of 0.96%, corresponding to 5 m

3 of hydrogen absorbed in the alloy during the experiment. The total hydrogen desorption time, during which the exothermic reaction was analysed, amounted to 9480 s. The material properties used in the numerical calculation are listed in

Table 2.

The amount of hydrogen desorbed from the alloy was not identical to the hydrogen flow rate, as measured using a mass flow meter. This was because the pressure of gaseous hydrogen between the alloy grains changed. A correction may only be made with a known free volume value between the grains of the metal hydride

VFV,n; this was identified in an experiment with a helium-pressurised system, in which the gas was not being absorbed into the alloy. Subsequently, the real desorbed hydrogen flow rate was calculated using the following equation:

wherein

Qv,des is the volumetric flow rate of the desorbed hydrogen (m

3·s

−1);

Qv is the volumetric flow rate measured at the outlet from the tank (m

3·s

−1); and d

τ is the elementary time change (s).

The output of heat generated in the metal hydride was calculated by using the measured values and adjusting the following differential Equation (2):

wherein

Pis is the internal source of the heat generated in the metal hydride alloy (W) and

qis is the released reaction heat (J·m

−3).

The external surface of the tank’s insulation is subject to the Newton equation for flow and the Fourier equation near the wall for heat conduction:

wherein

k is the thermal conductivity of the steel tank (W·m

−1·K

−1);

n is the distance in the direction of the normal line to the interface area (m);

hamb is the overall heat transfer coefficient for the area between the tank surface and the surrounding environment (W·m

−2·K

−1);

Tw is the temperature of the surface of MH tank’s wall (K); and

Tamb is the ambient temperature (K).

We calculated the 3D geometry of the object, consisting of a cylindrical tank containing the MH alloy, with an internal diameter of 150 mm and a wall thickness of 4.5 mm.

In addition to the aforementioned mathematical description of the heat transport calculation, we conducted a 3D calculation of the flow of the heat-carrying medium (water) in the area between the tank’s shells; due to low Reynolds number values, the Shear Stress Transport (SST) turbulence model was used to calculate the turbulent kinetic energy k and specific dissipation rate

ω, using the following equations:

wherein

k is the turbulent kinetic energy and

ω is the specific dissipation rate.

The calculations also included creating the following continuity equation:

wherein

ρ is the fluid density (kg·m

−3);

t is the time (s); and

U is fluid flow speed (m·s

−1).

The numerical calculation used the following momentum equation:

The Total Energy Equation was as follows:

wherein

htot is the total enthalpy related to the static enthalpy

h(

T,

p), calculated as follows:

By applying the boundary conditions (

Table 3) identified during the experiment, the equations above were used to identify the thermal field inside the tank in a defined time interval.

The temperature of water at the tank inlet was defined as a function of time, while the values were based on the experiments conducted.

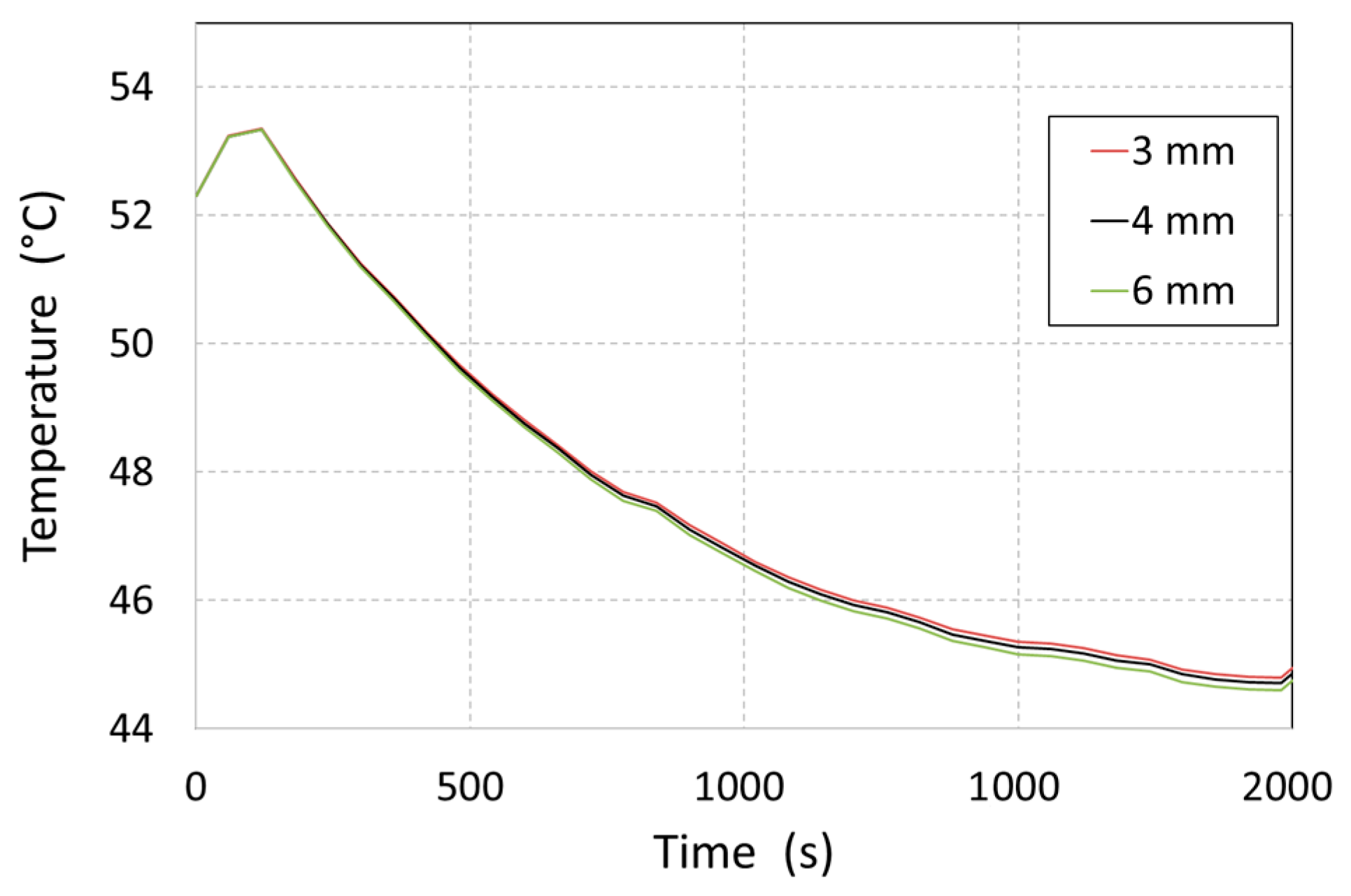

In the numerical solution, the tank’s geometry was segmented into a finite number of volume elements. The tank mesh created comprised 5.87 million elements, while the geometry of the MH material consisted of 2.6 million elements at an average mesh size of 4 mm. In order to validate the fact that the average mesh size had no effect on the resulting MH temperature values, a sensitivity analysis was carried out, and the element size was changed from 4 mm to 3 and 6 mm. For this, we numerically calculated the thermal field over the period of the first 2000 s of hydrogen release (

Figure 6).

The maximum difference between the MH temperatures, as identified by comparing numerical calculations for the 6 and 4 mm mesh sizes, amounted to 0.26%. With a further increase in mesh density to 3 mm, the difference decreased to 0.19% (between 3 mm and 4 mm). With an average MH domain mesh size of 3 mm, the total mesh size amounted to 8.75 million elements. This resulted in a significant increase in the calculation time and had only a minimal effect on the results’ accuracy.

During heat-carrying fluid flow, the mesh was denser near the wall, with a dimensionless thickness of the first element of y+ = 1.

4. Analytical Calculation of the Thermal Field

An analytical calculation of the thermal field may be conducted while assuming a homogeneous thermal field in the tank, since the total average temperature of the tank only changes over time. Such a calculation was necessary in order to correctly identify the tank’s thermal constant, which is indicative when defining the time necessary for tank re-heating and maintaining the required pressure without taking hydrogen absorption and desorption into account (a closed tank). This value may be calculated using the power balance described by the differential equation expressing a correlation between the input thermal power

Pt,w, the output thermal power for the heat passing through the tank’s insulation and the energy accumulated per time unit:

wherein

Samb is the surface of the insulated tank through which heat is transferred to the surrounding environment (m

2);

t is the average temperature of MH (°C); Σ(

m·

c) is the total heat capacity of the tank (J·K

−1); and

τ is the time (s).

The input thermal power may be identified as being dependent on the difference between the input temperature of the water and the average temperature of the MH, while the proportionality constant

ψ1 may be calculated using the circulating water heat balance:

wherein

tw,

in is the temperature of the water at the tank inlet (°C);

hMH is the overall heat transfer coefficient between the water and the MH material (W·m

−2·K

−1);

Sw is the surface area of the internal shell of the tank through which heat is transported into the MH material (m

2);

Qm,

w is the water mass flow rate (kg·s

−1); and

cw is the water heat capacity (J·kg

−1·K

−1).

A differential Equation (11) was used to calculate the changes in the average temperature of the MH tank, while parameters

ψ2 and

ψ3 represent the substitution of the constants in the following equations:

The time constant of the system was calculated as the quotient of the total heat capacity of the tank divided by parameter

ψ2:

In order to identify an instant average temperature of the tank at a particular time, it is necessary to know the overall heat transfer coefficient between water and the MH material. Because heat transport between the circulating water and the metal hydride cannot be analytically defined due to the implemented internal ribs, parameter hMH was identified by comparing the numerical and the analytical results.

The time constant, as identified using Equation (17), expresses the time in which the required tank temperature will reach 63.2% of the projected stabilised MH material temperature during exponential tank heating. For practical use in a vehicle, tank heating should last at least 3 · τc in order to reach 95% of the projected temperature.

5. Results and Discussion

Storage is a key aspect of efficient hydrogen use in energy systems. The best-known hydrogen storage methods include metal hydrides, compressed gas or liquefied hydrogen, and storage using chemical hydrogen carriers. From a technical point of view, compression is the simplest solution for hydrogen storage; however, at a pressure of 350–700 bar, it achieves only a low volumetric energy density and requires the use of huge storage systems. Liquefied hydrogen facilitates higher energy density; however, liquefication is energy-intensive (30–40% of the hydrogen energy content) and requires the application of cryogenic conditions at −253 °C. Chemical forms, such as ammonium or liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs), provide the benefits of a very high energy density and easy handling. However, their disadvantage is that hydrogen release from those compounds requires additional catalytic processes, imposing the risk of impurity formation. Metal hydrides (MHs) facilitate achieving a high volumetric energy density at a relatively low pressure (5–30 bar); as such, they increase system safety. They thus generally exhibit excellent safety and stability; however, their practical usability is limited by their mass and temperature requirements, which bring a wide range of challenges.

The present study combines experimental measurements, numerical simulations, and the analytical modelling of a storage tank made of a metal hydride, the MNTZV-159 tank. This analytical calculation facilitated the identification of an average tank temperature as a function of time.

By applying the baseline and boundary conditions based on the experimental measurements, we performed a numerical calculation to identify the tank’s thermal field as a function of time.

Due to the fact that it was impossible to measure the thermal field across the entire cross-section of the certified tank, we compared the numerical calculations with the experimentally identified values using the surface temperature (

Figure 7), which was measured in the centre of the tank’s bottom.

The maximum absolute difference between the measured and calculated surface temperature values amounted to 1.9 °C.

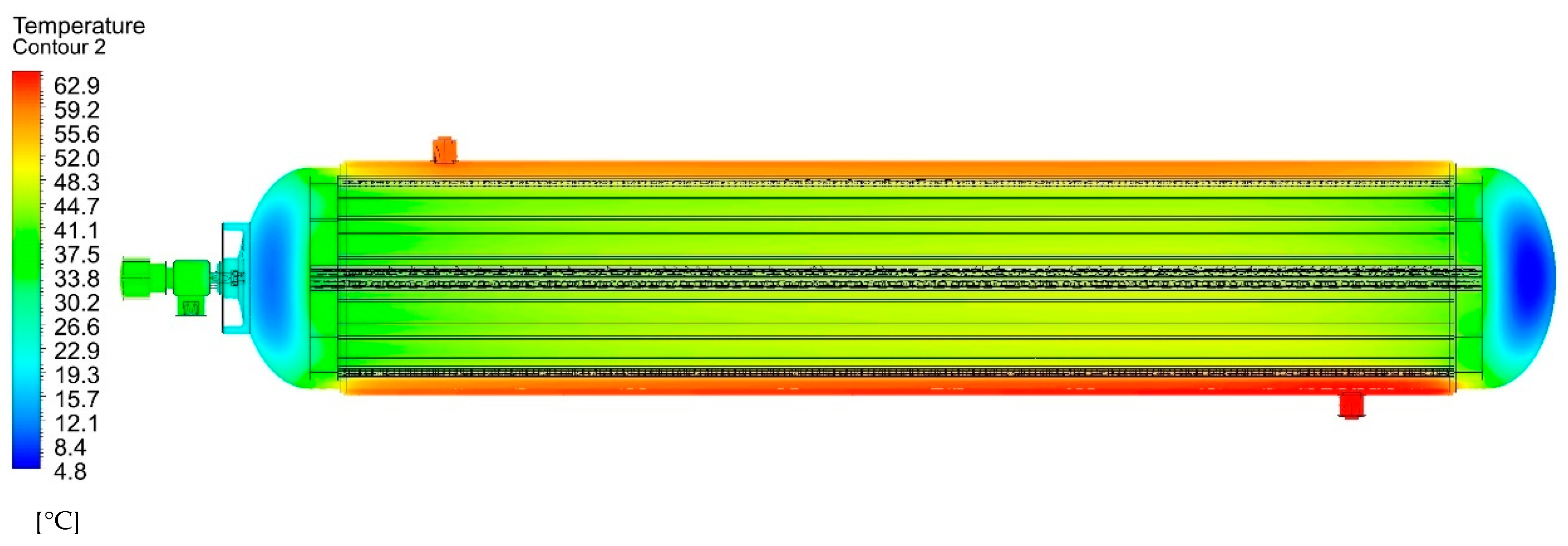

Figure 8 shows the thermal field in the longitudinal plane of the tank at 1950 s, i.e., the time when the flow rate began to gradually decrease, with the aim of regulating the output pressure. The tank’s central region was intensively heated by the shell heat exchanger, while a decrease in the temperature to 4.8 °C was only observed in its terminal sections, where internal ribs were not present.

The transverse cross-section in the tank’s centre (

Figure 9) visibly shows the effect of the internal ribs, which improve heat removal towards its shell. The minimum temperature of the MH material in the tank core was 44.4 °C, while the maximum temperature next to the shell was 60.9 °C. The highest circulating water temperature was observed along the periphery in the space between the shells.

At places where the primary and secondary fins are in contact with the vessel’s internal shell, the achieved temperature was lower (yellow regions seen in

Figure 9); this resulted in better heat transport into the heat-carrying fluid in the space between the shells. This was caused by an increase in the temperature gradient between the shell and fluid. The heat transport intensification was more significant near the primary fins, which had a larger surface area. The regions between the fins (orange regions seen in

Figure 9) exhibited a higher temperature, which was caused by the direct contact between the powder MH material and the tank shell. By integrating the temperatures in the elementary volumes of the MH material, the average temperature was identified as a function of time (

Figure 10) during dynamic hydrogen release.

The resulting average MH material temperature values were affected by the inaccuracy of the sensors used in the experiment. When the boundary conditions—including the hydrogen flow rate with an upper limit of measurement inaccuracy (for the flow meter used, this was ±0.5% of the measured value plus ±0.1% of the total range), as well as the temperature of the heating water with a lower limit of inaccuracy in the temperature sensor (resistance tolerance: ±2%; at a measurement temperature of 65 °C, it corresponded to an inaccuracy of ±0.68 °C)—were taken into account, the resulting values were delimited by the lower dashed curve (

Figure 10). This represents the minimum temperatures at given moments in time due to measurement uncertainties. The curve was constructed based on separate numerical calculations with modified boundary conditions. The measurement uncertainty-derived maximum deviation of the average MH material temperature was observed at 1980 and amounted to ±0.87 °C.

In the first part of the measurement, at 0–2000 s, the average temperature of the metal hydride gradually decreased from the initial 52.3 °C to 44.8 °C, despite the shell heating caused by increased hydrogen release (

Figure 10). This also caused a decrease in the operational pressure to 8 bar. The gradual reduction in the desorbed hydrogen flow rate resulted in a decrease in the total value of the internal generated heat, which again caused a temperature increase; however, at that time, there was already a low concentration of hydrogen in the MH alloy.

In the real-life operation of a fuel cell, with hydrogen being supplied from the MH tank, it is possible to gradually reduce its power, or to turn it off for the time necessary for repeated temperature increase in the whole alloy volume. In such a case, the input power required to operate a transport vehicle may be withdrawn from an electric battery. Such a procedure will result in an increase in the pressure so that the fuel cell may be used, even at higher power levels.

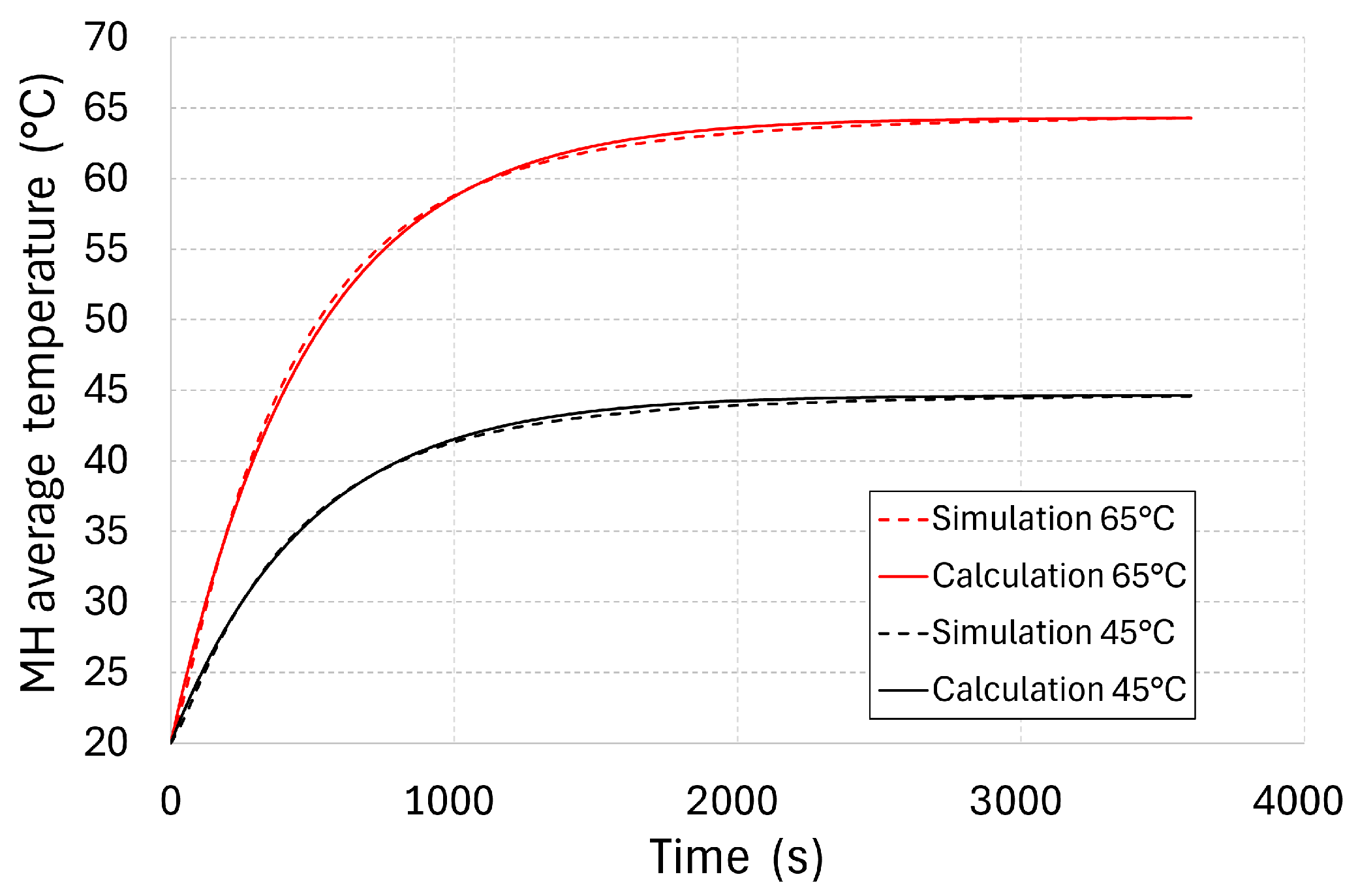

The time required for stabilising the thermal field, as well as for increasing the average temperature to 63.2% of the difference between the baseline temperature and that of the supply water, is defined by the time constant described by Equation (17). The missing parameter for identifying its value is the overall heat transfer coefficient

hMH. In order to identify its value, a numerical simulation of the tank’s heating was carried out with a baseline temperature of 20 °C, using water at baseline temperatures of 45 and 65 °C. The increase in the average temperature, as calculated via numerical simulation, is presented in

Figure 11 for both baseline water temperature variants.

During MH tank heating, the equilibrium pressure increased; this depends on the alloy’s concentration and average temperature. With a hydrogen mass concertation of 0.9 wt.% (50% capacity) to a temperature of 65 °C, the pressure will increase to 26.4 bar, in accordance with the used alloy’s PCI curve. The analytical calculations were performed using Equation (13) through (17), with the use of input data applicable to the MNTZV-159 tank, as listed in

Table 4.

In these calculations, the overall heat transfer coefficient hMH was changed, with the aim of reaching the minimum absolute average deviation between the temperature analytically calculated with the simplified model and that calculated numerically by applying the finite volume method. The minimum deviations were reached at hMH = 247 W·m−2·K−1. At a water temperature of 45 °C at the tank inlet, the average absolute deviation amounted to 0.46%, while the maximum deviation was 2.5%. At a water temperature of 65 °C at the tank inlet, the average absolute deviation amounted to 0.55%, while the maximum deviation was 3.6%.

The value of hMH, identified as described above, corresponds to the tank’s time constant (483 s). Using this value, it is possible to set the transport vehicle tank re-heating time in order to increase the pressure again, provided that the tank still contains a sufficient amount of hydrogen. During operation, it is beneficial to use multiplied values of τc, at which the average tank temperature approaches that of the supply water. The time constant for different MH storage tank geometries is affected not only by the masses and thermal capacities of the individual components, but also by the heat loss into the surrounding environment, the flow rate of the heat-carrying fluid, and the overall heat transfer coefficient hMH. The value of hMH itself is affected by the geometry and shape of the internal ribs, rising with a better heat transport into the tank’s core. This article describes the process of identifying the value of hMH, which then may be used to identify the time constant of any tank’s geometry.

6. Conclusions

The results of the experimental measurements, numerical simulations and analytical calculations confirmed that, with the use of an appropriate thermal management system, MNTZV-159 metal hydride tanks are capable of providing a stable hydrogen supply for fuel cells in mobile applications. The identification of the tank time constant—483 s—provides a crucial parameter in designing control strategies that must respond to dynamic loading changes. The numerical simulations showed that the internal ribs are of fundamental importance; they provide a more even distribution of heat and minimise temperature gradients. Meanwhile, the analytical calculations facilitated a simple and sufficiently accurate description of the system’s behaviour.

From a practical point of view, our research indicates that in order to ensure a continuous hydrogen supply, it is necessary to consider regulated release and the temporary use of electric energy from a battery, which may cover the instantaneous energy demands of the vehicle during the regeneration of the tank’s thermal field. Such an approach will increase the operational stability of the vehicle and facilitate maintaining the fuel cell in an optimal mode, even with more complex driving cycles.

Moreover, the results indicate directions for further study. Researchers should focus on developing novel metal hydride materials with a higher capacity and better kinetic properties, as well as on optimising tank geometry, with an emphasis on effective heat transfer and the integration of the tanks into complex thermal management systems for vehicles. Other promising avenues would be to test the system’s cyclic stability in real-life operations, including vibrations, temperature changes and a variety of release profiles, and to carry out a financial assessment of the commercialisation of such tanks, taking into account not only their technical parameters, but also their production and operating costs. The present article therefore provides important knowledge for the further development and implementation of metal hydride tanks in the field of sustainable mobility.