Performance Analysis and Evaluation of Vegetable Cold-Chain Drying Equipment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characteristic Analysis of Cold-Chain Vegetable Drying Equipment

2.1. Overview of Vegetable Drying Equipment

2.1.1. Analysis of the Technical Characteristics of Vegetable Drying

- Hot-air drying (HAD): one of the most traditional and widely used drying technologies, remains prevalent in the fruit and vegetable industry due to its operational simplicity, high throughput, and broad applicability. However, it suffers from low energy efficiency and high consumption, primarily due to exhaust gases carrying away substantial latent and sensible heat, coupled with thermal losses from equipment and material heating. Moreover, prolonged and non-uniform drying often causes severe quality degradation in vegetables, including deterioration in texture and flavor [7,8]. The majority of Jew’s ear mushrooms in the market are dried with traditional drying techniques [9].

- Heat pump drying (HPD): offers relatively high energy efficiency and preserves heat-sensitive components in vegetables, thus enhancing product quality [10]. However, it entails higher capital costs and relies on conventional eco-friendly refrigeration. Low-temperature HPD systems can reduce energy consumption through controlled atmospheric evaporation, yielding improved food quality. In peanut drying, HPD strikes a favorable balance between drying efficiency and the preservation of color, nutritional components, and oil quality [11].

- Infrared drying (IR): employs electromagnetic waves of 0.75–1000 µm, matching the vibrational frequencies of food molecules to induce resonance and energy transfer directly into the product without heating the surrounding air, thereby minimizing quality degradation [12]. Consequently, IR offers high drying efficiency, low energy consumption, and minimal material damage [13].

- Freeze drying (FD): freezes moisture in fruit into a solid state, then sublimates it directly into vapor, effectively preserving nutrients [14]. Precise control of freezing rates and moisture-loss parameters is required to balance product quality with energy consumption.

- Microwave drying (MD): ions and water molecules within the material oscillate more vigorously under the electromagnetic field, raising surface temperature and causing moisture evaporation [15]. Current challenges include uneven heating due to large sample sizes, irregular geometries, and heterogeneous tissue composition.

- Combined hot-air and microwave drying (HAD-MD): offers simple operation, excellent drying performance, and produces rehydrated products with superior color and texture compared to traditional HAD, while significantly reducing drying time and energy use; however, microwave-induced unevenness remains a key challenge.

- Combined hot-air and infrared drying (HAD-ID): because infrared energy is directly absorbed by the material, this method prevents structural and compositional damage caused by surface-to-core temperature gradients [16]. Internal vaporization and pressure-driven moisture movement preserve texture and flavor [17], enabling shorter drying times while maintaining quality.

- Combined hot-air and vacuum freeze-drying (HAD-FD): can reduce drying time and costs while ensuring product quality. A study on Jerusalem artichoke chips demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach, where optimized processing conditions significantly enhanced product color, texture, and flavor profile, achieving a quality comparable to freeze-dried products but with higher energy efficiency [18].

- Vacuum drying (VD): conducted in a sealed chamber under pressure significantly below atmospheric pressure. Vacuum drying lowers the water boiling point under reduced pressure, enabling rapid low-temperature dehydration with relatively low energy consumption. Its low-temperature, oxygen-free environment excellently preserves heat-sensitive components, natural color, and flavor while preventing oxidation. For instance, water chestnuts have been shown to retain a well-preserved microstructure following vacuum drying [19]. However, the vacuum system requires high equipment investment and energy consumption, which, combined with its typical batch-operation mode, results in high operating costs and limited processing capacity.

- Combined microwave and vacuum drying (MD-VD): effectively lowers process temperatures and, while maintaining efficiency, maximizes retention of texture and nutritional content. A study on shiitake mushrooms demonstrated that ultrasonic-assisted MD-VD not only better preserved polysaccharide content compared to conventional hot-air drying but also modified the molecular weight and apparent viscosity of the polysaccharides, contributing to a more homogeneous product [20].

- Freeze drying–microwave vacuum drying (FD-MVD): integrates three drying techniques to yield high-quality dried products while leveraging the high efficiency, rapid processing, and low energy consumption of microwave vacuum drying [21].

- Air impingement drying (AID): employs heated, pressurized gas directed through nozzles onto the material surface for heating and drying. The high-speed jets impinge on the surface, reducing the thermal boundary layer and the resistance to heat and mass transfer, thereby significantly enhancing the heat exchange rate and shortening the drying duration [22]. This technique offers a higher convective heat transfer coefficient, a faster drying rate, and lower energy consumption while maintaining product quality.

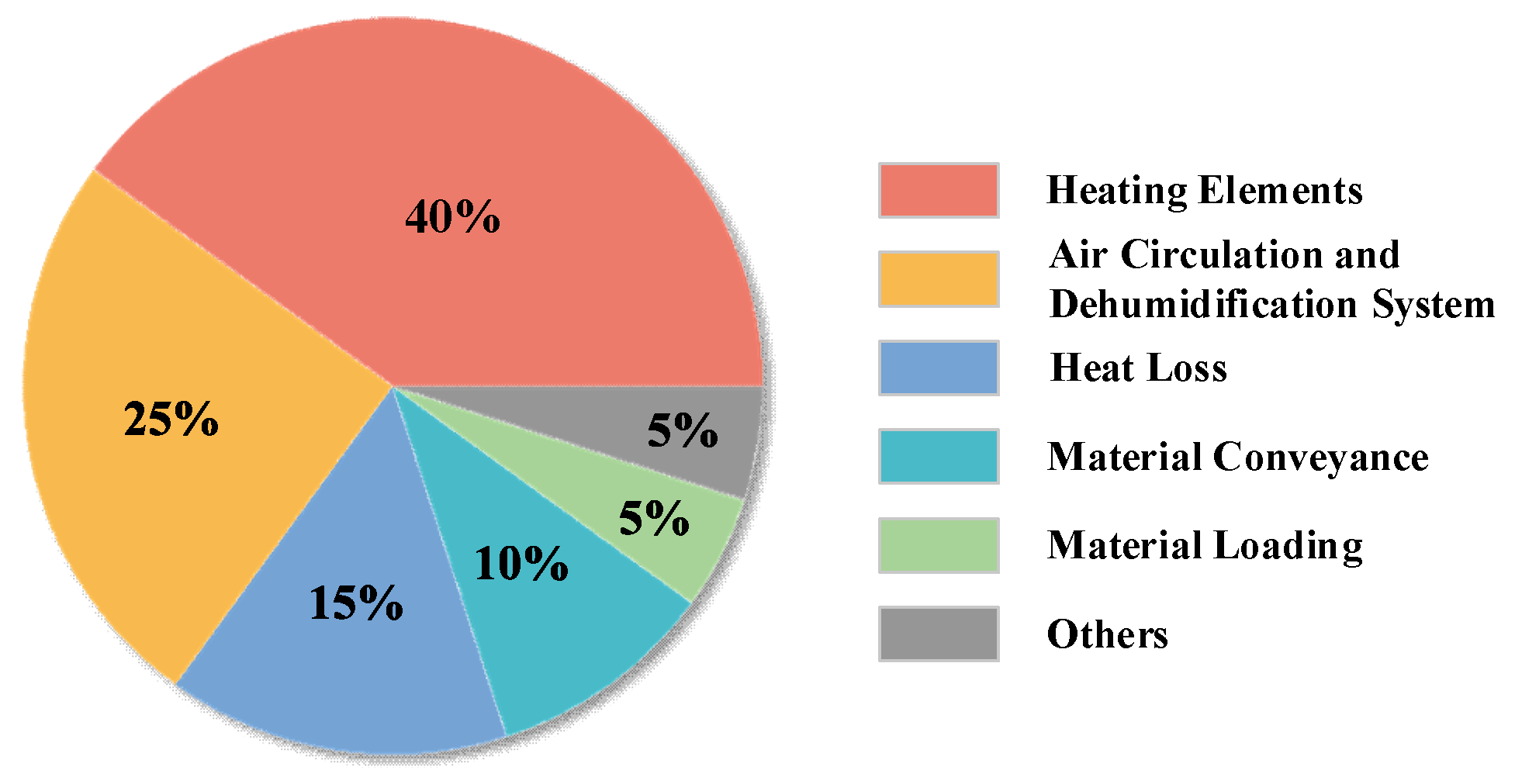

2.1.2. Energy Consumption Analysis of Vegetable Drying Equipment

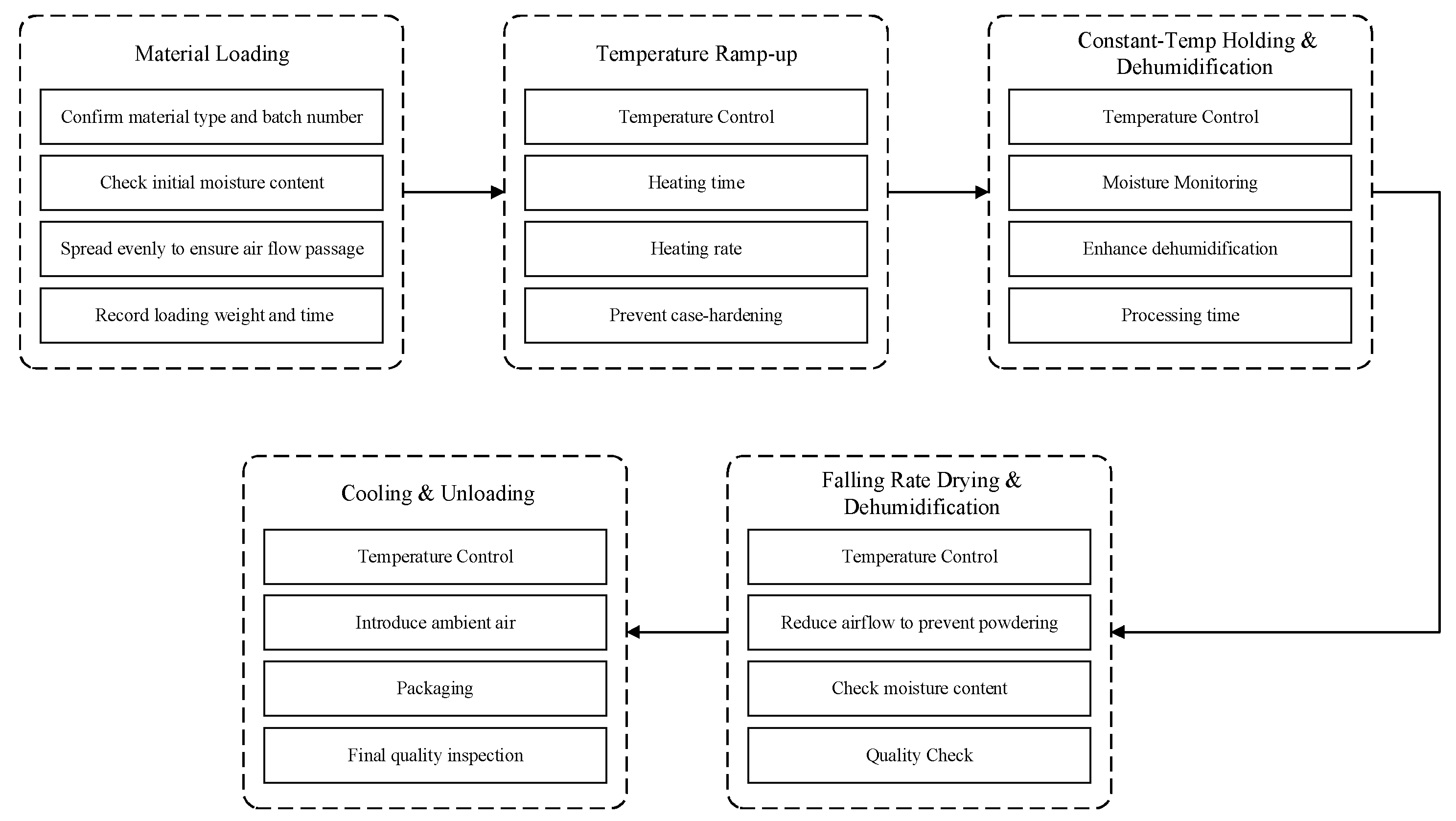

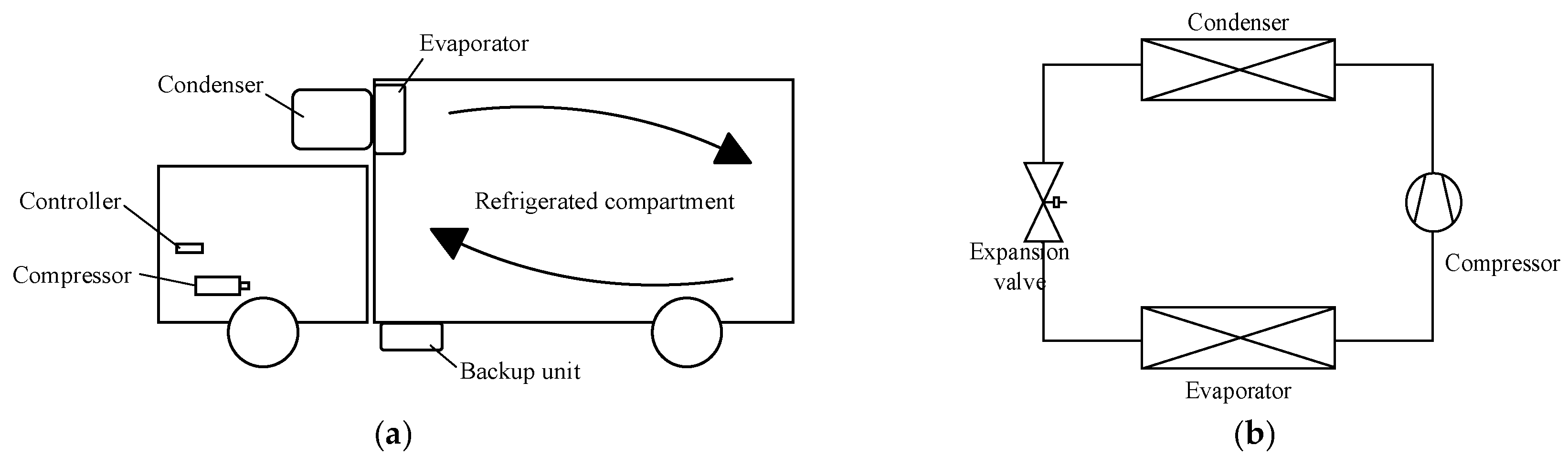

2.2. Characteristics of Vegetable Cold-Chain Equipment

2.2.1. Composition of Vegetable Cold-Chain Equipment

2.2.2. Energy-Consumption Analysis of Vegetable Cold-Chain Equipment

3. Research on the Evaluation Index System of Vegetable Drying Cold-Chain Equipment

3.1. Analysis of Drying Evaluation Indicators

3.2. Analysis of Energy Consumption Evaluation Metrics

3.2.1. Energy Consumption of Vegetable Drying Equipment

3.2.2. Energy Consumption of Vegetable Cold Chain Equipment

4. Fusion Analysis Based on Boosting and Multiple Kernel Functions

4.1. Evaluation Method

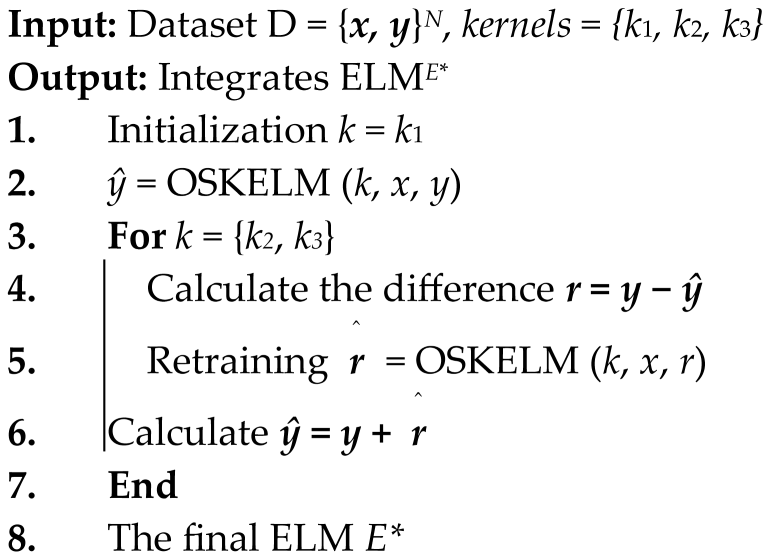

| Pseudocode of boosting-OSKELM |

|

4.2. Case Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, L. Application of Vacuum Freeze-Drying Technology in Agricultural Product Processing in China. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2020, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.M.; Jin, X.; Bi, J.F.; Hu, L.; Qiu, Y.; Lu, J. Effect of Ultrasonic—Assisted Sugar Osmotic Pretreatment on Quality and Hygroscopicity of Vacuum Freeze—Dried Peach Chips. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabin, D.; Ming, X.; Shelie, S.M. Overview of cold chain development in China and methods of studying its environmental impacts. Environ. Res. Commun. 2020, 2, 122002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwin, K.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.A. Global advancement of solar drying technologies and its future prospects: A review. Sol. Energy 2021, 221, 559–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.S. Handbook of Industrial Drying, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, J.; Váquiro, H.; Benedito, J.; Telis-Romero, J. Thermophysical properties of mango pulp (Mangifera indica L. cv. Tommy Atkins). J. Food Eng. 2010, 97, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskan, M. Drying, shrinkage and rehydration characteristics of kiwifruits during hot air and microwave drying. J. Food Eng. 2001, 48, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ramaswamy, H.; Qu, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, S. Combined radio frequency-vacuum and hot air drying of kiwifruits: Effect on drying uniformity, energy efficiency and product quality. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 56, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásványi, B.; Sik, B.; Lakatos, E.; Schott, Z.; Székelyhidi, R. Assessing the texture profile and optimizing the temperature and soaking time for the rehydration of hot air-dried Auricularia auricula-judae mushrooms. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, J.; Sheng, J.F.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Zheng, F.; Feng, D.; You, X. Heat Pump Drying Characteristics and Mathematical Model of Yam. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 30, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Bo, J.; Zhu, W.; Chen, P.; Jiang, M.; Chen, G. Comprehensive analysis of changes in the drying characteristics, quality, and metabolome of peanuts by different drying methods. Food Res. Int. 2025, 221, 117625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adak, N.; Heybeli, N.; Ertekin, C. Infrared drying of strawberry. Food Chem. 2017, 219, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingol, G.; Wang, B.; Zhang, A.; Pan, Z.; McHugh, T.H. Comparison of water and infrared blanching methods for processing performance and final product quality of French fries. J. Food Eng. 2014, 121, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.G.; Silveira, A.M.; Freire, J.T. Freeze-drying characteristics of tropical fruits. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cavieres, L.; Pérez-Won, M.; Tabilo-Munizaga, G.; Jara-Quijada, E.; Díaz-Álvarez, R.; Lemus-Mondaca, R. Advances in vacuum microwave drying (VMD) systems for food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.F.; Li, S.; Han, X.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, D.; Hao, J. Quality evaluation and drying kinetics of shitake mushrooms dried by hot air, infrared and intermittent microwave-assisted drying methods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 107, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kan, H.; Fan, F. Vacuum impregnation and drying of iron-fortified water chestnuts. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Gao, W.; Lv, S.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, C. Enhanced quality and optimized volatile profile of Jerusalem artichoke chips: A combined approach of pretreatment optimization and hybrid vacuum freeze-hot air drying. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Xie, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Mowafy, S.; Guo, J. Mechanism of freezing treatment to improve the efficiency of hot air impingement drying of steamed Cistanche deserticola and the quality attribute of the dried product. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 195, 116472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, Y.; Meng, P.; Tu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, L.; Tian, Y. Impact of combined ultrasonic and microwave vacuum drying on physicochemical properties and structural characteristics of polysaccharides from shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 115, 107283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.K.; Ni, H. Infrared and hot-air-assisted microwave heating of foods for control of surface moisture. J. Food Eng. 2002, 51, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Liu, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Niu, L.; Zhang, M. Evaluation of freeze drying combined with microwave vacuum drying for functional okra snacks: Antioxidant properties, sensory quality, and energy consumption. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 82, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, H.T.; Sarker, S.H. Comprehensive energy analysis and environmental sustainability of industrial grain drying. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, R.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Liu, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, M. Effects of Different Drying Methods on the Nutrition and Physical Properties of Momordica Charania. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2017, 50, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Huang, J.Q.; Lu, F.; Zhou, W.; Liu, P. A Novel Compound Fault-tolerant Method Based on Online Sequential Extreme Learning Machine with Cycle Reservoir for Turbofan Engine Direct Thrust Control. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 108059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazeri-Gh, M.; Nekoonam, A. Gas Path Component Fault Diagnosis of an Industrial Gas Turbine Under Different Load Condition Using Online Sequential Extreme Learning Machine. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 135, 106115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Classification Level | Main Category | Specific Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Appearance quality | Chromaticity value | Brightness value |

| 2 | Redness | ||

| 3 | Yellowness | ||

| 4 | Sensory quality | Textural characteristics | Apparent density |

| 5 | Microstructure | ||

| 6 | Shrinkage rate | ||

| 7 | Hardness; | ||

| 8 | Elasticity | ||

| 9 | Adhesiveness | ||

| 10 | Chewiness | ||

| 11 | Water activity | ||

| 12 | Rehydration ratio | ||

| 13 | Taste values | Sourness | |

| 14 | Saltiness | ||

| 15 | Umami | ||

| 16 | Bitterness | ||

| 17 | Astringency | ||

| 18 | Sweetness | ||

| 19 | Sensory evaluation indicators | Color | |

| 20 | Odor | ||

| 21 | Shape | ||

| 22 | Mouthfeel | ||

| 23 | Nutritional quality | Bioactive components | Antioxidant activity |

| 24 | Vitamin C content | ||

| 25 | Total phenolic content | ||

| 26 | Carbohydrates | Total sugar content | |

| 27 | Reducing sugar content | ||

| 28 | Proteins and amino acids | Protein content | |

| 29 | Total amino acid content |

| No. | Classification Level | Main Category | Specific Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Energy consumption Characteristics | Input energy | Inlet air heat transfer rate |

| 2 | Inlet material heat transfer rate | ||

| 3 | Output energy | Outlet air heat transfer rate | |

| 4 | Material heat transfer rate | ||

| 5 | Moisture evaporation energy | ||

| 6 | Dryer wall heat loss | ||

| 7 | System efficiency | Thermal efficiency | |

| 8 | Energy consumption per unit moisture evaporation | ||

| 9 | Performance coefficient | ||

| 10 | Operating parameters | Temperature | Set temperature |

| 11 | Actual temperature | ||

| 12 | Humidity | Design humidity | |

| 13 | Actual humidity | ||

| 14 | Air velocity | Set air velocity | |

| 15 | Actual air velocity | ||

| 16 | Material | Slice thickness | |

| 17 | Time | Drying time | |

| 18 | Environmental impact | Environmental conditions | Ambient humidity |

| 19 | Ambient temperature | ||

| 20 | Carbon emissions | Carbon emissions per unit output | |

| 21 | Energy type | Electric energy | |

| 22 | Gas | ||

| 23 | Other energy sources |

| No. | Classification Level | Main Category | Specific Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Storage energy consumption | Energy-consumption characteristics | Cooling capacity |

| 2 | Heat ingress into the cargo compartment | ||

| 3 | Heat ingress due to air and water-vapor leakage | ||

| 4 | System-component performance | Compressor operating frequency | |

| 5 | Evaporator-fan speed | ||

| 6 | Condenser-fan speed | ||

| 7 | Expansion-valve flow coefficient | ||

| 8 | Temperature parameters | Condensing temperature | |

| 9 | Evaporating temperature | ||

| 10 | Refrigerant characteristics | Type of refrigerant | |

| 11 | Refrigerant charge amount | ||

| 12 | Environmental parameters | Ambient temperature | |

| 13 | Ambient humidity | ||

| 14 | Carbon emissions | ||

| 15 | Transportation energy consumption | Energy consumption during transport | Transport distance |

| 16 | Cargo mass | ||

| 17 | Loading/unloading energy consumption | Loading method | |

| 18 | Loading/unloading duration | ||

| 19 | Other parameters | Ambient temperature | |

| 20 | Vehicle insulation performance |

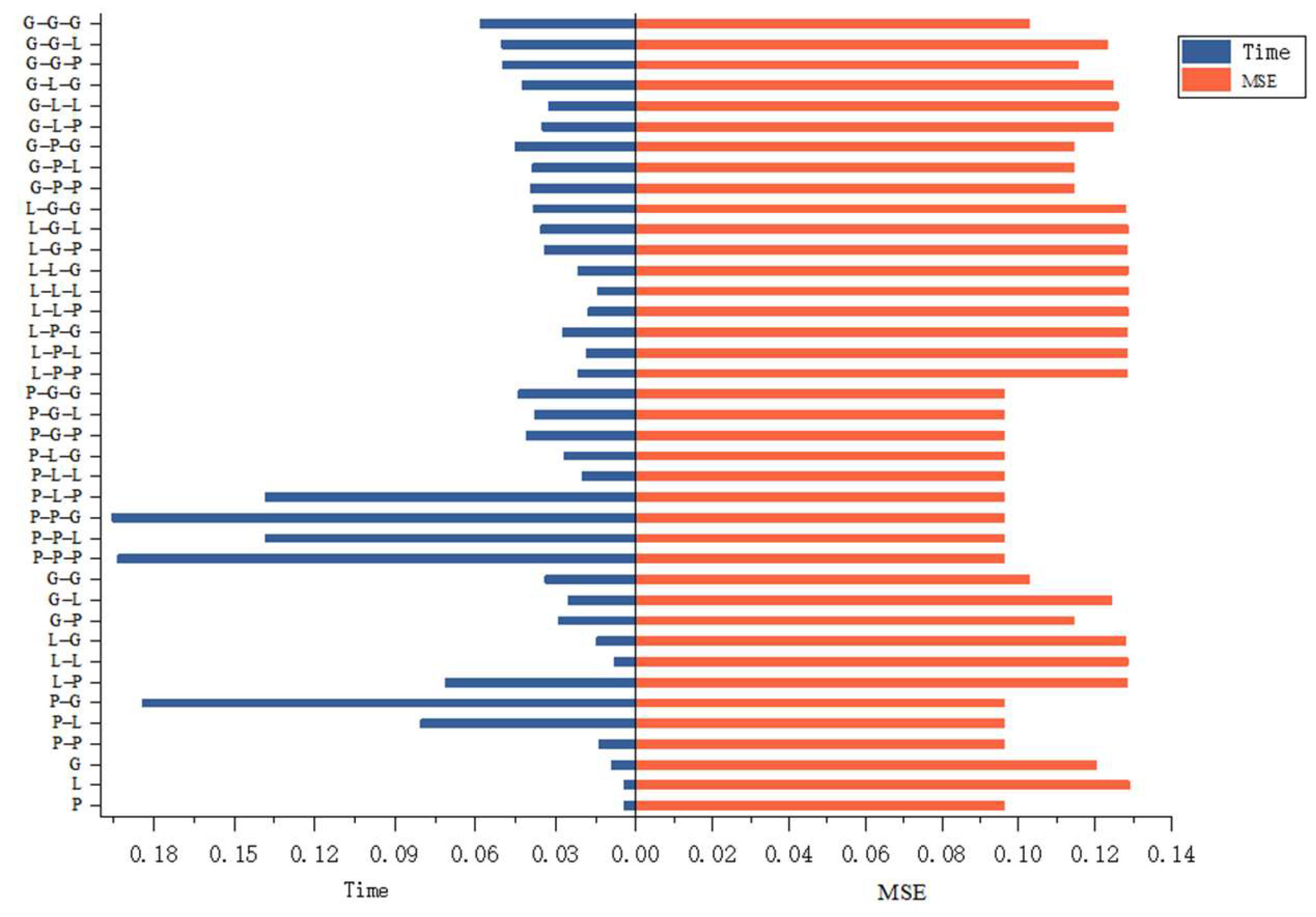

| No. | Sequences | (a, b, p, σ) | Time (s) | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0044 | 0.0962 |

| 2 | L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0043 | 0.1289 |

| 3 | G | (1, 1, 1, 100) | 0.0093 | 0.1203 |

| 4 | P–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0137 | 0.0962 |

| 5 | P–L | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0802 | 0.0962 |

| 6 | P–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.1843 | 0.0962 |

| 7 | L–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0711 | 0.1284 |

| 8 | L–L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0081 | 0.1285 |

| 9 | L–G | (1, 1, 1, 100) | 0.0146 | 0.1279 |

| 10 | G–P | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0288 | 0.1145 |

| 11 | G–L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0252 | 0.1244 |

| 12 | G–G | (1, 1, 1, 50) | 0.0338 | 0.1028 |

| 13 | P–P–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.1932 | 0.0962 |

| 14 | P–P–L | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.1383 | 0.0962 |

| 15 | P–P–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.1953 | 0.0962 |

| 16 | P–L–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.1382 | 0.0962 |

| 17 | P–L–L | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0200 | 0.0962 |

| 18 | P–L–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0266 | 0.0962 |

| 19 | P–G–P | (3, 1, 3, 50) | 0.0409 | 0.0962 |

| 20 | P–G–L | (3, 1, 3, 50) | 0.0377 | 0.0962 |

| 21 | P–G–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0437 | 0.0962 |

| 22 | L–P–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0216 | 0.1284 |

| 23 | L–P–L | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0185 | 0.1284 |

| 24 | L–P–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0273 | 0.1284 |

| 25 | L–L–P | (3, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0179 | 0.1285 |

| 26 | L–L–L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0141 | 0.1285 |

| 27 | L–L–G | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0216 | 0.1285 |

| 28 | L–G–P | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0341 | 0.1284 |

| 29 | L–G–L | (1, 1, 1, 50) | 0.0356 | 0.1285 |

| 30 | L–G–G | (1, 1, 1, 100) | 0.0381 | 0.1279 |

| 31 | G–P–P | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0394 | 0.1145 |

| 32 | G–P–L | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0386 | 0.1145 |

| 33 | G–P–G | (3, 1, 3, 100) | 0.0452 | 0.1145 |

| 34 | G–L–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0350 | 0.1248 |

| 35 | G–L–L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0327 | 0.1259 |

| 36 | G–L–G | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0426 | 0.1246 |

| 37 | G–G–P | (3, 1, 3, 10) | 0.0495 | 0.1154 |

| 38 | G–G–L | (1, 1, 1, 10) | 0.0500 | 0.1232 |

| 39 | G–G–G | (1, 1, 1, 50) | 0.0579 | 0.1028 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, M.; Ling, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, M.; Wang, X. Performance Analysis and Evaluation of Vegetable Cold-Chain Drying Equipment. Processes 2025, 13, 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123810

Xie M, Ling X, Wang P, Xu M, Wang X. Performance Analysis and Evaluation of Vegetable Cold-Chain Drying Equipment. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123810

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Minglu, Xiaoyan Ling, Pan Wang, Man Xu, and Xiaoting Wang. 2025. "Performance Analysis and Evaluation of Vegetable Cold-Chain Drying Equipment" Processes 13, no. 12: 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123810

APA StyleXie, M., Ling, X., Wang, P., Xu, M., & Wang, X. (2025). Performance Analysis and Evaluation of Vegetable Cold-Chain Drying Equipment. Processes, 13(12), 3810. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123810