1. Introduction

Carbonaceous shale is a typical weak rock formation widely distributed in the central and southwestern regions of China. It is characterized by low strength, high clay content, and a tendency to soften upon water exposure. Long-term exposure to dry–wet cycles accelerates the damage and failure of carbonaceous shale, making it a critical challenge in engineering hazard prevention and control [

1,

2]. The process of rock deformation and failure is accompanied by energy conversion and release, and the ultimate failure is a state instability phenomenon driven by internal energy [

3]. Therefore, the energy mechanism of rock damage and failure has been clarified by studying the energy conversion law during the deformation process of fractured carbonaceous shale under dry–wet cycles.

At present, scholars have conducted extensive research on the mechanical properties and energy evolution laws of rocks under dry–wet cycles. Existing research findings indicate that as the number of wet–dry cycles increases, the strength parameters of rock gradually decrease [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. He et al. [

9] studied the influence of dry–wet cycles on the crack propagation law of sandstone by using a numerical simulation. In addition, scholars have studied the acoustic emission characteristics of rocks under dry–wet cycles, and explored the influence of dry–wet cycles on the mechanism of rock damage and deterioration from the perspective of acoustic emission [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Zhu et al. [

14] determined the characteristic stresses of marble with different moisture contents using the crack volume strain method, and studied the distribution characteristics of the main frequency of acoustic emission at the characteristic stress points. Xia et al. [

15] analyzed the characteristic stress response law and fracture precursor of granite under different dynamic disturbance damage conditions. Liu et al. [

16] investigated the influence of pre-existing flaws on the full-field strain evolution and characteristic stress levels of rock. Pu et al. [

17] found that the dry–wet cycle reduced the energy transfer efficiency, resulting in the discretization of the force chain and crack field. Lou et al. [

18] investigated the failure characteristics and energy evolution of three types of hole-fissured sandstone under dry–wet cycles. Sun et al. [

19] found that the energy consumption density decreases approximately linearly with the increase in dry–wet cycles, and the higher the loading rate, the more sensitive the energy consumption density is to the dry–wet cycle.

During the process of rock deformation and failure, the critical stresses at each stage are known as the crack characteristic stresses, which generally comprise the crack closure stress, crack initiation stress, crack damage stress, and peak stress. Investigating the crack characteristic stress and energy characteristics of rock is of great theoretical significance for clarifying the mechanism of rock damage and failure. However, the above research results mainly focus on peak stress and energy characteristics, and there are few studies considering the influence of dry–wet cycles, fissure angle, and confining pressure. Therefore, in this paper, a triaxial compression failure test of fractured carbonaceous shale under dry–wet cycles was carried out to analyze the influence laws of dry–wet cycles, fissure angle, and confining pressure on the crack characteristic stresses and energy characteristics of carbonaceous shale.

2. Principle of Energy Calculation

The failure of rock mass is related to the accumulation, release, and dissipation of energy in rocks. Based on the first law of thermodynamics, the following equations hold [

20].

where

,

, and

represent the total energy, elastic strain energy, and dissipation energy, respectively.

In the principal stress space, the energy of the rock unit is as follows:

where

,

, and

are the first, second, and third principal stresses, respectively.

,

, and

are the strains corresponding to the first, second, and third principal stresses, respectively.

From Hooke’s law, the following can be assumed:

By substituting Equation (4) into Equation (3), we obtain the following:

where

is the unloading elastic modulus in the linear elastic stage and

is Poisson’s ratio. To simplify calculations,

is replaced by the initial elastic modulus. The validity of this substitution is justified in Ref. [

21].

Under conventional triaxial compression conditions, where the confining pressure

, the total energy, elastic strain energy, and dissipated energy of the rock can be determined based on the concept of definite integration:

3. Experimental Method and Results

3.1. Experimental Method

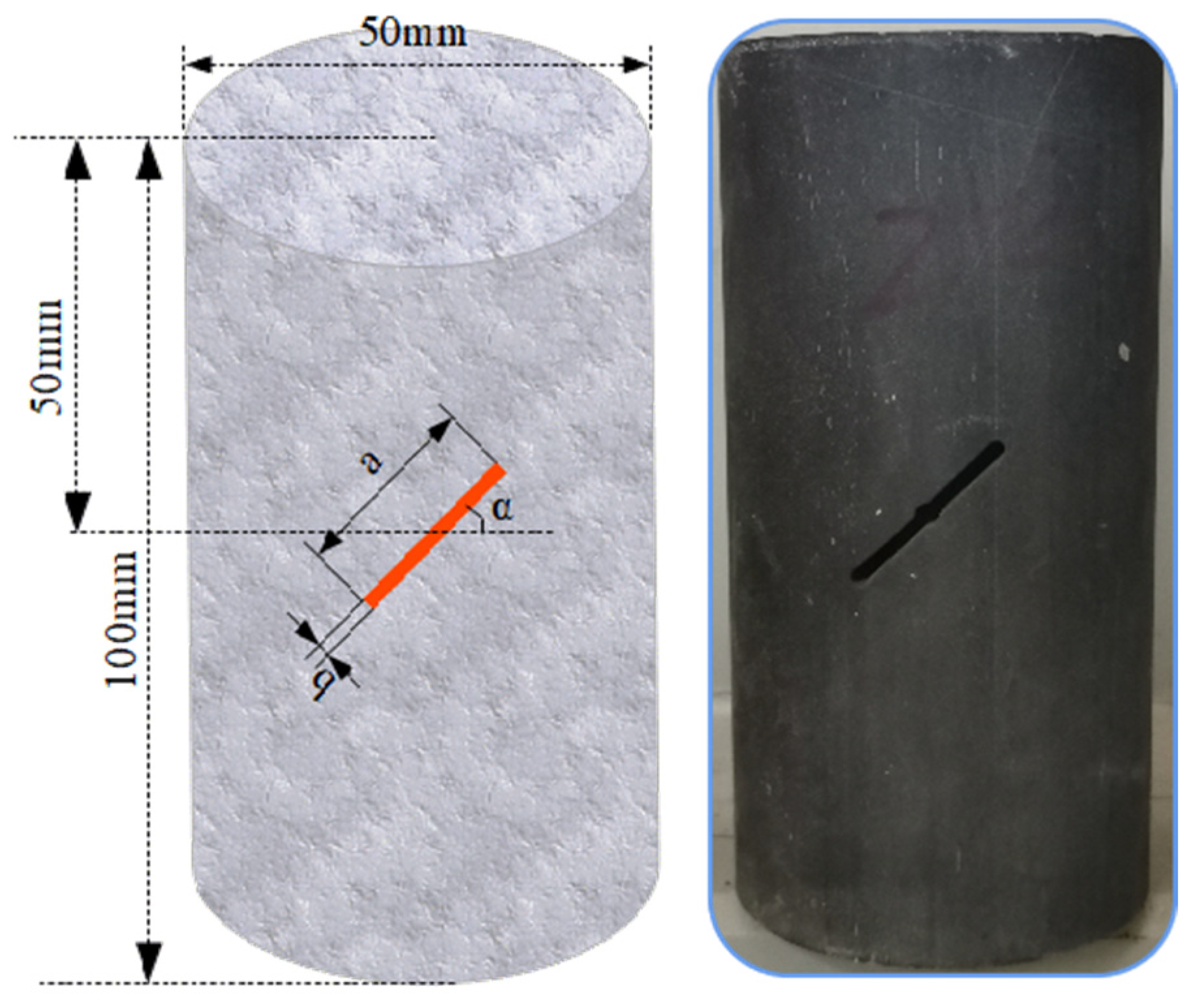

The carbonaceous shale was obtained from the Longlang Expressway, Hunan, China. All samples were shaped into cylinders with dimensions of ϕ50 mm × 100 mm based on the test method suggested by the International Society for Rock Mechanics. Then, the prefabricated fissures were processed on all samples using a water knife to simulate rock defects.

Figure 1 shows the geometric distribution and parameters of the fissures. The prefabricated fissure length and width were unchanged at a = 20 mm and b = 1 mm. In order to well-characterize the influence law of fissure angle on the strength of carbonaceous shale, the fissure angles were set at 0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°, respectively.

The dry–wet cycle test scheme was designed using the test method according to the method for determining the physical and mechanical properties of coal and rock (GB/T 23561.5-2009) [

22]. In one dry–wet cycle, the carbonaceous shale was placed in a water container to absorb water readily for 48 h and then dried in a thermostatic chamber at 105 °C for 24 h. The number of dry–wet cycles was set at 0, 5, 10, and 15 times, and the confining pressure set at 0, 2, 4 and 6 MPa. The samples after the dry–wet cycle treatment were subjected to triaxial compression tests using the MTS815 rock mechanics test system (

Figure 2). The application rate was 0.05 MPa/s. After stabilization, axial stress was increased at 0.1 kN/s until specimen failure.

3.2. Stress–Strain Curve

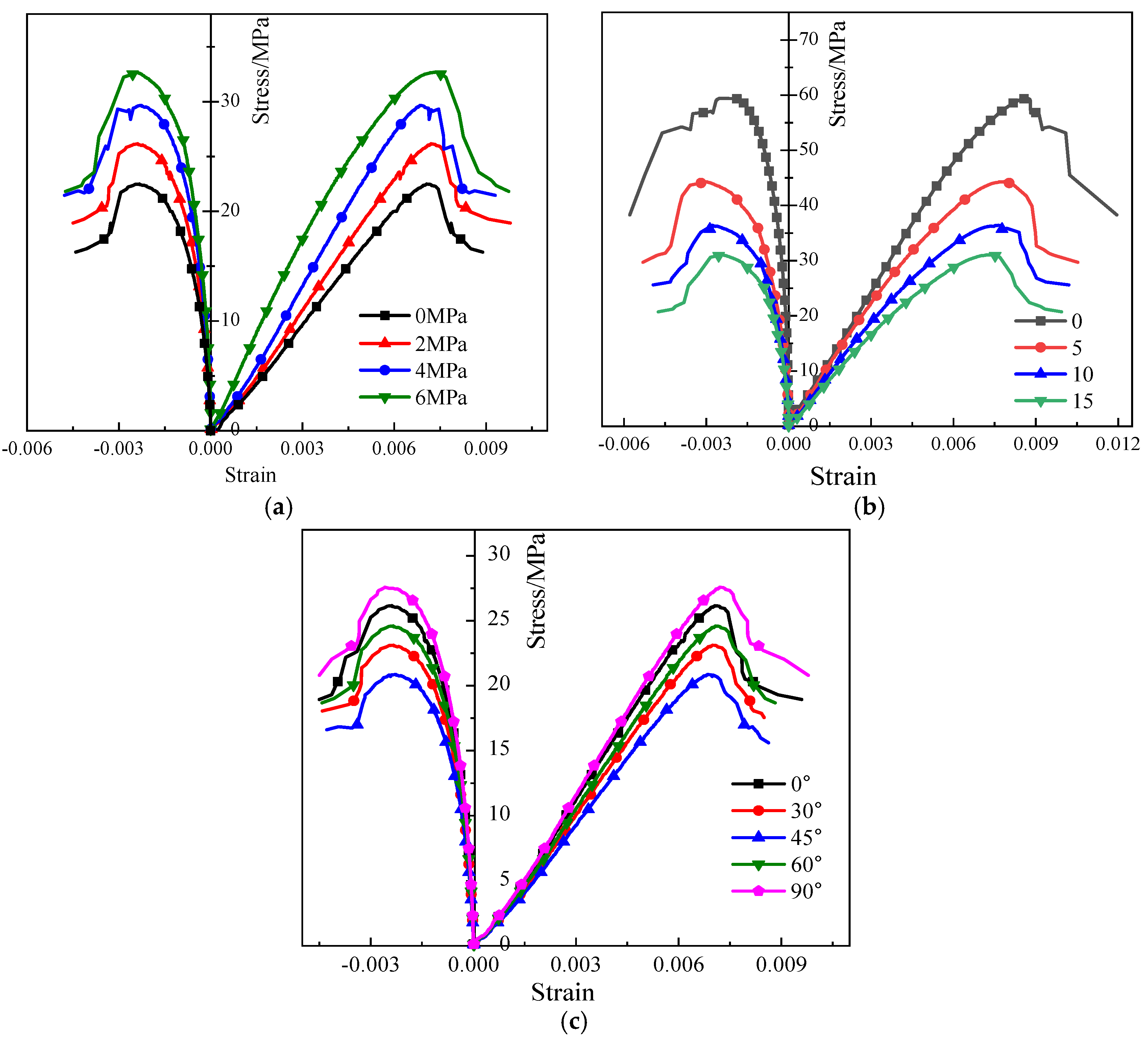

Considering the similarity of stress–strain curves during triaxial compression failure of fractured carbonaceous shale under dry–wet cycles, this paper selects the stress–strain curves of some samples, as shown in

Figure 3.

As shown in

Figure 3, the stress–strain curve of specimens is collectively influenced by dry–wet cycles, fissure angle, and confining pressure. The stress–strain curve of the specimen also exhibits a plastic–elastic–plastic growth trend before reaching the peak stress point. An increase in confining pressure results in a increase in the growth rate of the stress–strain curve, and the plastic stage near the peak stress becomes more pronounced (

Figure 3a). An increase in dry–wet cycles results in a decrease in the growth rate of the stress–strain curve, and the plastic stage near the peak stress becomes more pronounced (

Figure 3b). An increase in fissure angle results in a decrease first and then increase in the growth rate of the stress–strain curve (

Figure 3c).

3.3. Variation Law of Characteristic Stresses

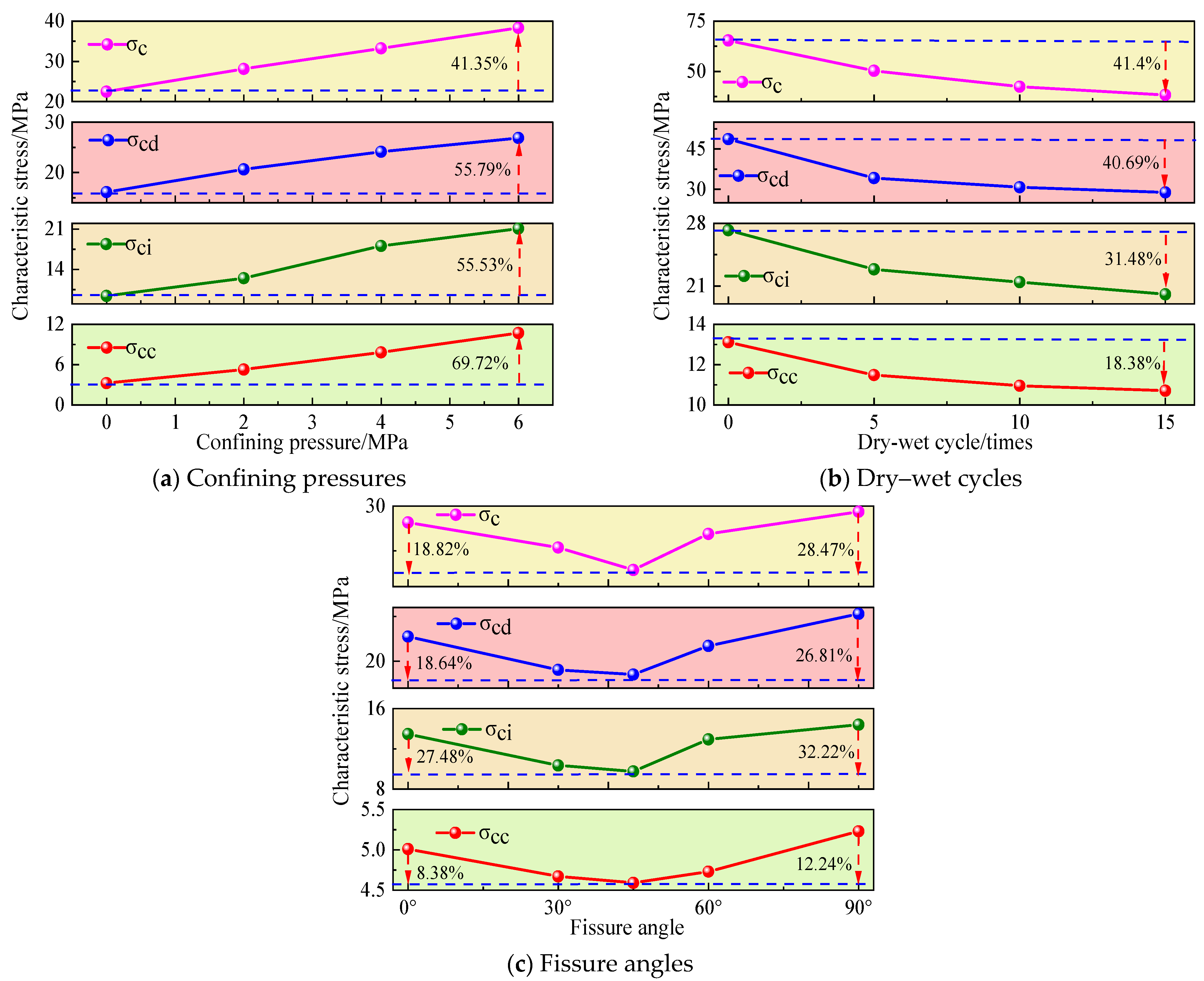

This study adopts the dissipated energy rate method proposed by the authors to determine the crack characteristic stresses. The detailed calculation process can be found in the literature [

23], and it will not be elaborated here. Representative stress–strain curves of samples were selected, and the variation curves of the crack characteristic stress of carbonaceous shale with confining pressure, dry–wet cycle, and fissure angle were obtained by using the dissipated energy rate method, as shown in

Figure 4.

As evidenced by

Figure 4a, when the confining pressure increases from 0 MPa to 6 MPa, the closure stress, initiation stress, damage stress, and peak stress of carbonaceous shale exhibit increases of 69.72%, 55.53%, 55.79%, and 41.35%, respectively. This quantitatively demonstrates that all characteristic stresses progressively escalate with elevated confining pressure.

From

Figure 4b, it can be observed that after 15 dry–wet cycles, the dried specimens exhibited reductions in closure stress, initiation stress, damage stress, and peak stress of 18.38%, 31.48%, 40.69%, and 41.4%, respectively. This indicates that characteristic stresses gradually decrease with the increase in the number of dry–wet cycles.

As the fissure angle increases from 0° to 90°, the closure stress, initiation stress, damage stress, and peak stress of the specimen first decrease and then increase, reaching their minimum values at a fissure angle of 45° and exhibiting a “V”–shaped variation trend (see

Figure 4c).

4. Energy Evolution Law

4.1. Energy Characteristics of Crack Characteristic Stresses

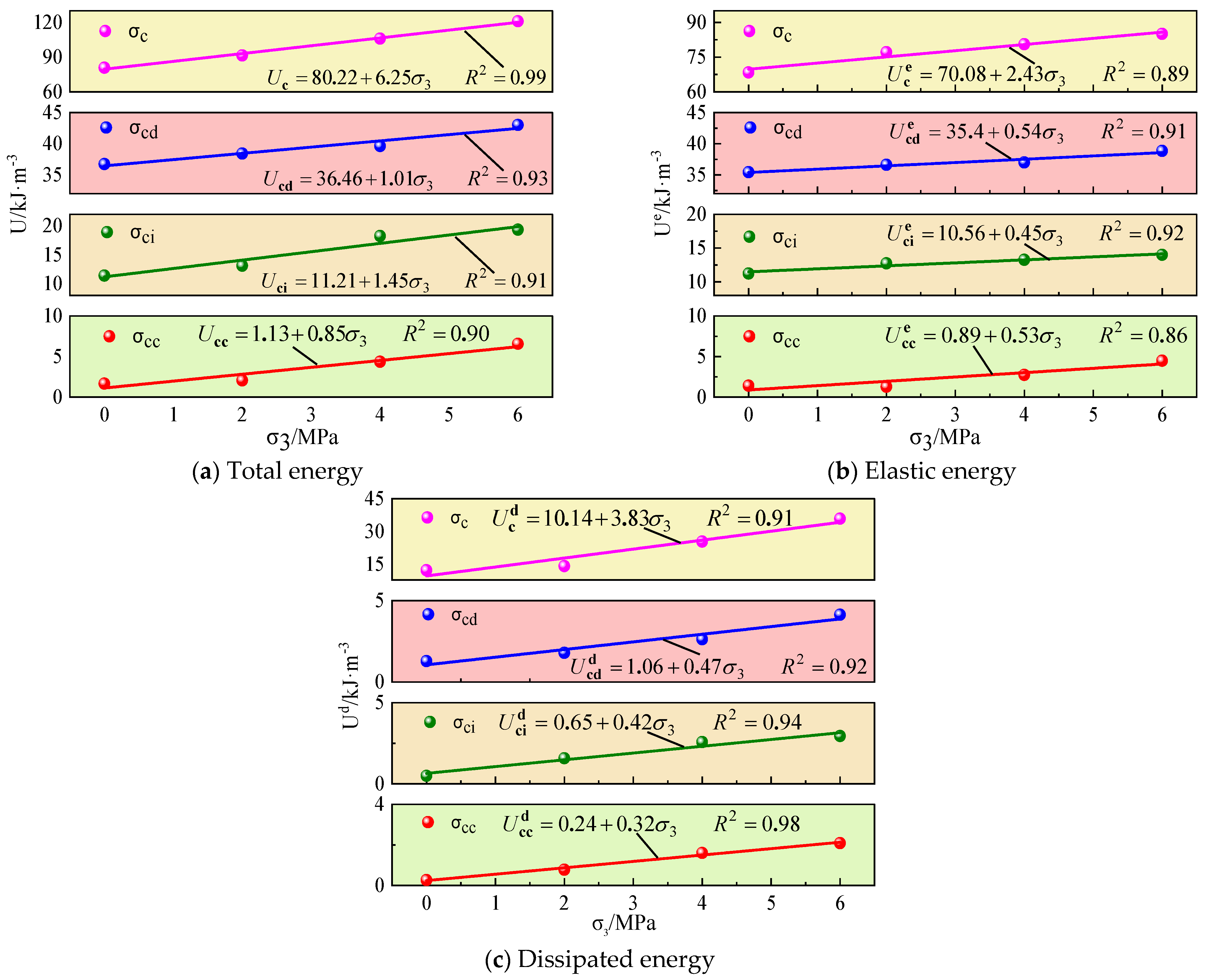

4.1.1. Influence Law of Confining Pressure

The energy indexes of the crack characteristic stress of specimen under different confining pressure are shown in

Figure 5.

As shown in

Figure 5, with the increase in confining pressure, the total energy, elastic energy, and dissipated energy of the crack characteristic stress of the samples gradually increase, indicating that confining pressure improves the internal energy storage performance of carbonaceous shale, inhibits the crack initiation and propagation of carbonaceous shale, and thereby enhances the deformation failure resistance of carbonaceous shale.

The least squares method was employed to fit various energy indexes, revealing that the total energy, elastic energy, and dissipated energy at characteristic stress points exhibit linear relationships with confining pressure. The general form of the fitting function is as follows:

where

represents the energy indicators at each characteristic stress point under different confining pressure conditions,

and

are the fitting coefficients, and

is confining pressure. The fitting correlation coefficients

range from 0.86 to 0.99, indicating good fitting results.

4.1.2. Influence Law of Dry–Wet Cycles

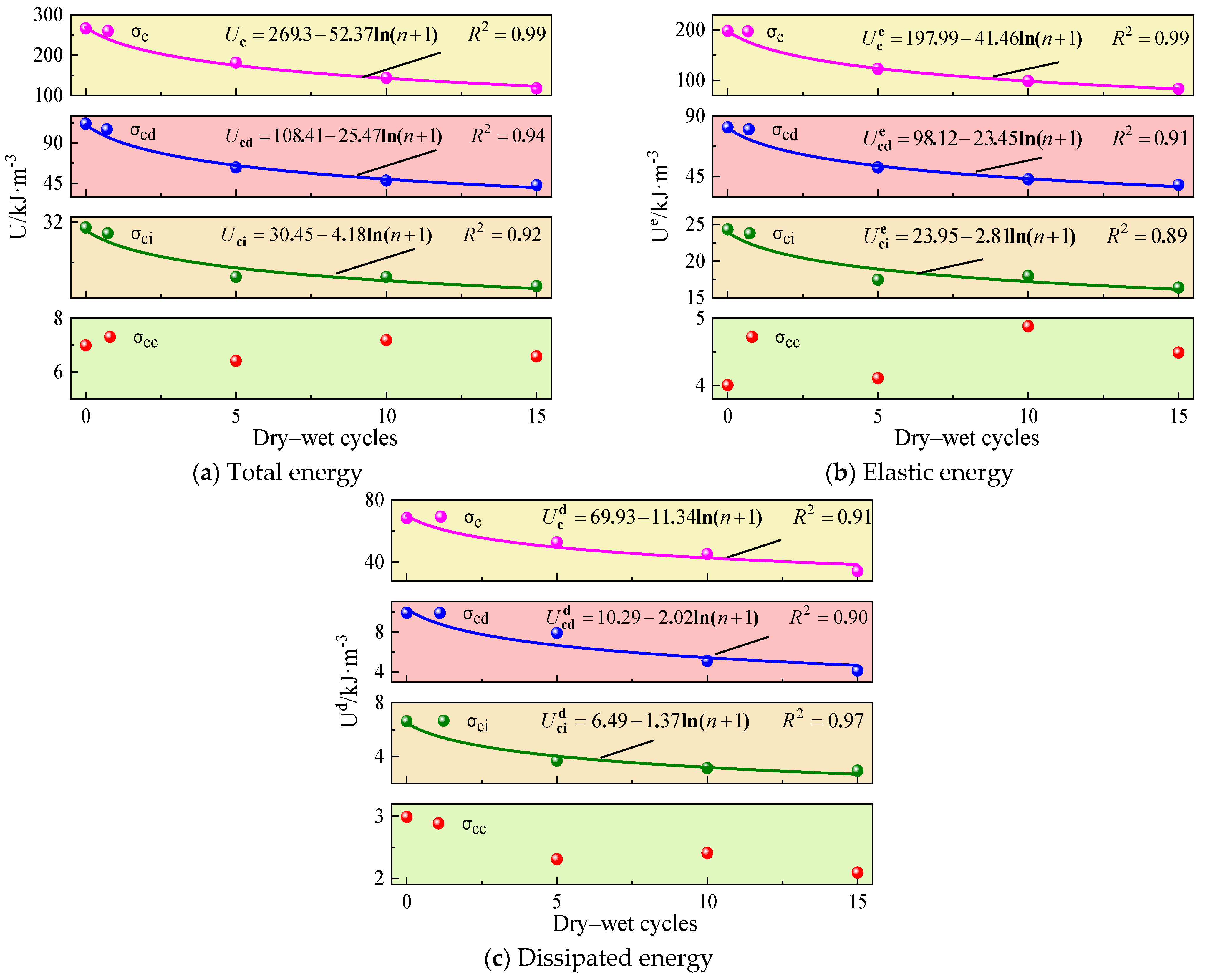

The energy indexes of the crack characteristic stress of specimen under dry–wet cycles are shown in

Figure 6.

From

Figure 6, apart from the crack closure stress, the energy indexes of other crack characteristic stresses decrease with increasing dry–wet cycles. Compared to the dry specimen, after 15 wet–dry cycles, the total energy of specimen at the crack initiation stress, damage stress, and peak stress decreased by 11.62, 68.52, and 145.71 kJ·m

−3, respectively. The elastic energy decreased by 7.94, 62.78, and 113.19 kJ·m

−3, while the dissipated energy decreased by 3.68, 5.74, and 32.52 kJ·m

−3. These results demonstrate that the energy absorption and storage capacities of carbonaceous shale gradually decrease with increasing dry–wet cycles. It indicates that the dry–wet cycle promotes crack initiation and propagation of carbonaceous shale, thereby reducing the ability of carbonaceous shale to resist deformation and failure.

The least squares method was employed to fit various energy indexes, revealing that the total energy, elastic energy, and dissipated energy at characteristic stress points exhibit logarithmic functional relationships with the number of wet–dry cycles. The general form of the fitting function is as follows:

where

represents the energy indicators at each characteristic stress point under dry–wet cycles,

and

are the fitting coefficients, and

is dry–wet cycles. The fitting correlation coefficients

range from 0.89 to 0.99, indicating good fitting results.

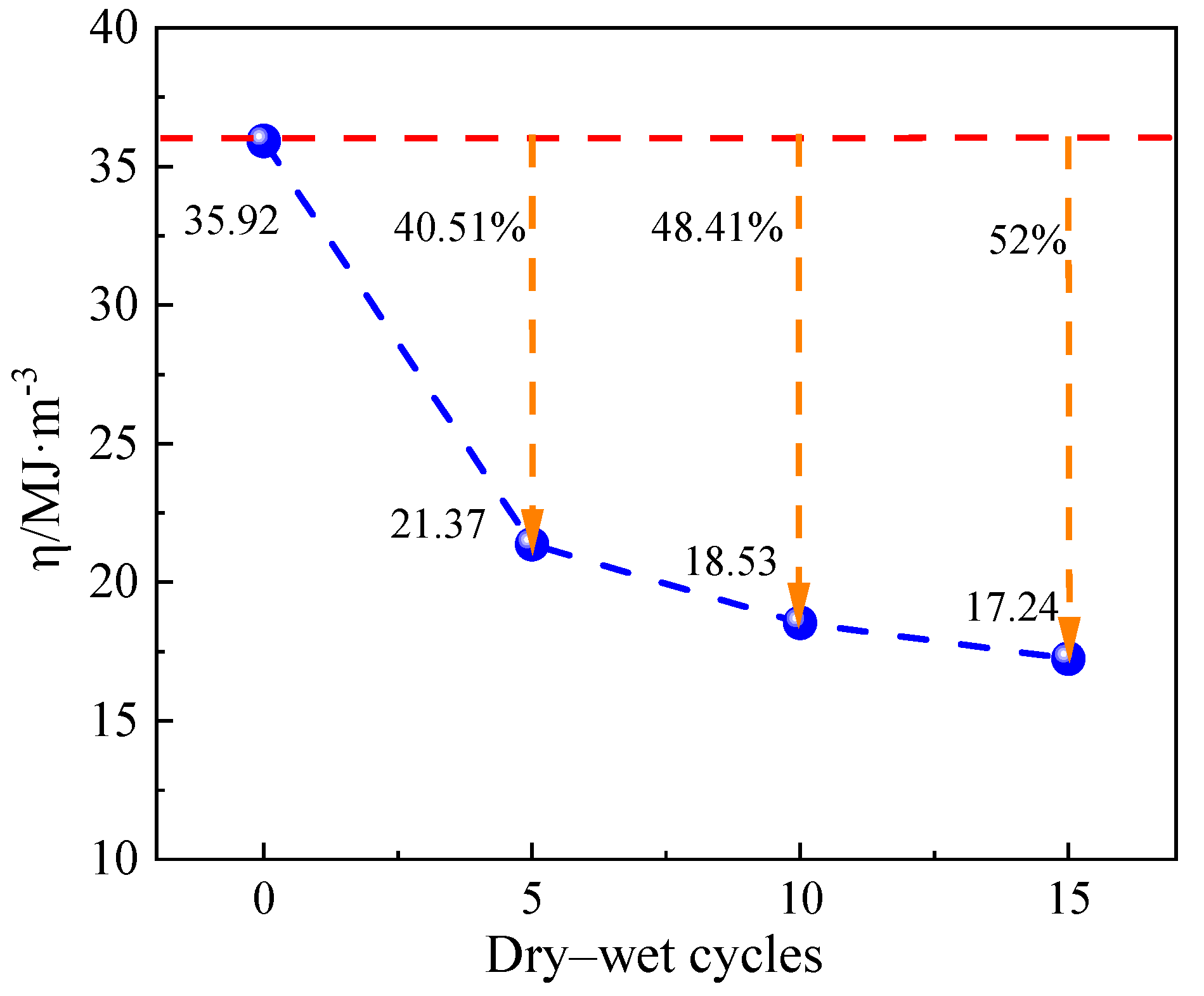

The elastic energy of the rock no longer increases after peak stress but is continuously released. Therefore, the post-peak elastic strain energy release rate

(

) can be defined to reflect the deformation and failure characteristics of the rock after the peak.

Figure 7 shows the variation curve of the post–peak elastic energy release rate of carbonaceous shale with dry–wet cycles.

As shown in

Figure 7, the post–peak elastic energy release rate gradually decreases with an increasing number of dry–wet cycles. When no dry–wet cycles are applied (0 cycles), the post–peak elastic strain energy release rate is 35.92 MJ·m

−3. After 5, 10, and 15 cycles, it decreases by 40.51%, 48.41%, and 52%, respectively. This indicates a gradual reduction in the intensity of rock failure, with enhanced ductile failure characteristics, leading to less violent rock bursts–consistent with the findings of academician He [

24]. In tunnel and coal mine roadway engineering, where rock burst hazards may occur, water injection into the rock mass can be employed as an engineering measure to reduce the likelihood of rock bursts. Additionally, as the number of dry–wet cycles increases, the rock exhibits more pronounced ductile behavior, retaining a certain residual strength over a relatively extended period. This provides favorable conditions for grouting fractured surrounding rock and implementing bolt support, thereby enhancing the stability of the surrounding rock.

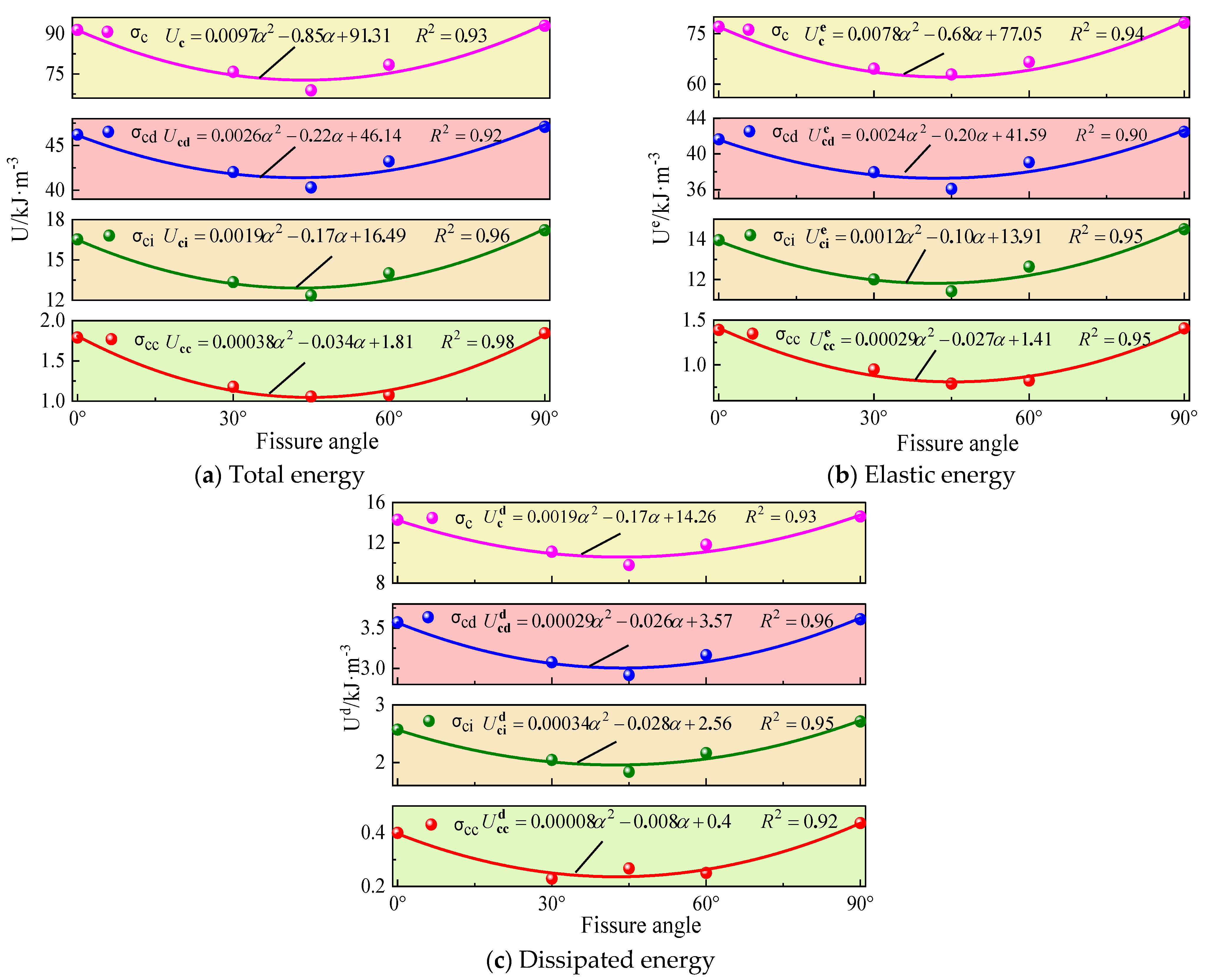

4.1.3. Influence Law of Fissure Angle

The energy indexes of the crack characteristic stress of specimens under different fissure angles are shown in

Figure 8.

As can be seen from

Figure 8, the variation patterns of various energy parameters at the characteristic stress are similar. The total energy, elastic energy, and dissipated energy all exhibit a “V”–shaped trend–first decreasing and then increasing with the growth of fissure angle, reaching their minimum values at 45°. Analysis of energy characteristics at peak stress reveals that when the fissure angle is 45°, both the total energy and elastic energy reach their minimum values (68.86 kJ·m

−3 and 59.06 kJ·m

−3 respectively), making the rock most prone to failure. Conversely, at 0° or 90°, these parameters reach their maximum values (total energy: 91.39 kJ·m

−3 and 92.9 kJ·m

−3; elastic energy: 77.1 kJ·m

−3 and 78.28 kJ·m

−3, respectively), indicating the highest resistance to failure. This demonstrates that rocks with 45° fissure angles have weaker energy absorption and storage capacities, resulting in lower resistance to failure. In contrast, rocks with 0° or 90° fissure angles possess stronger energy absorption and storage capacities, exhibiting greater failure resistance. As the fissure angle increases, the rock’s failure resistance follows a “strong–weak–strong” pattern.

The least squares method was employed to fit various energy indexes, revealing that the total energy, elastic energy, and dissipated energy at characteristic stress points exhibit quadratic functional relationships with the fissure angle. The general form of the fitting function is as follows:

where

represents the energy indicators at each characteristic stress point under fissure angle,

,

and

are the fitting coefficients, and

is the fissure angle. The fitting correlation coefficients

range from 0.89 to 0.99, indicating good fitting results.

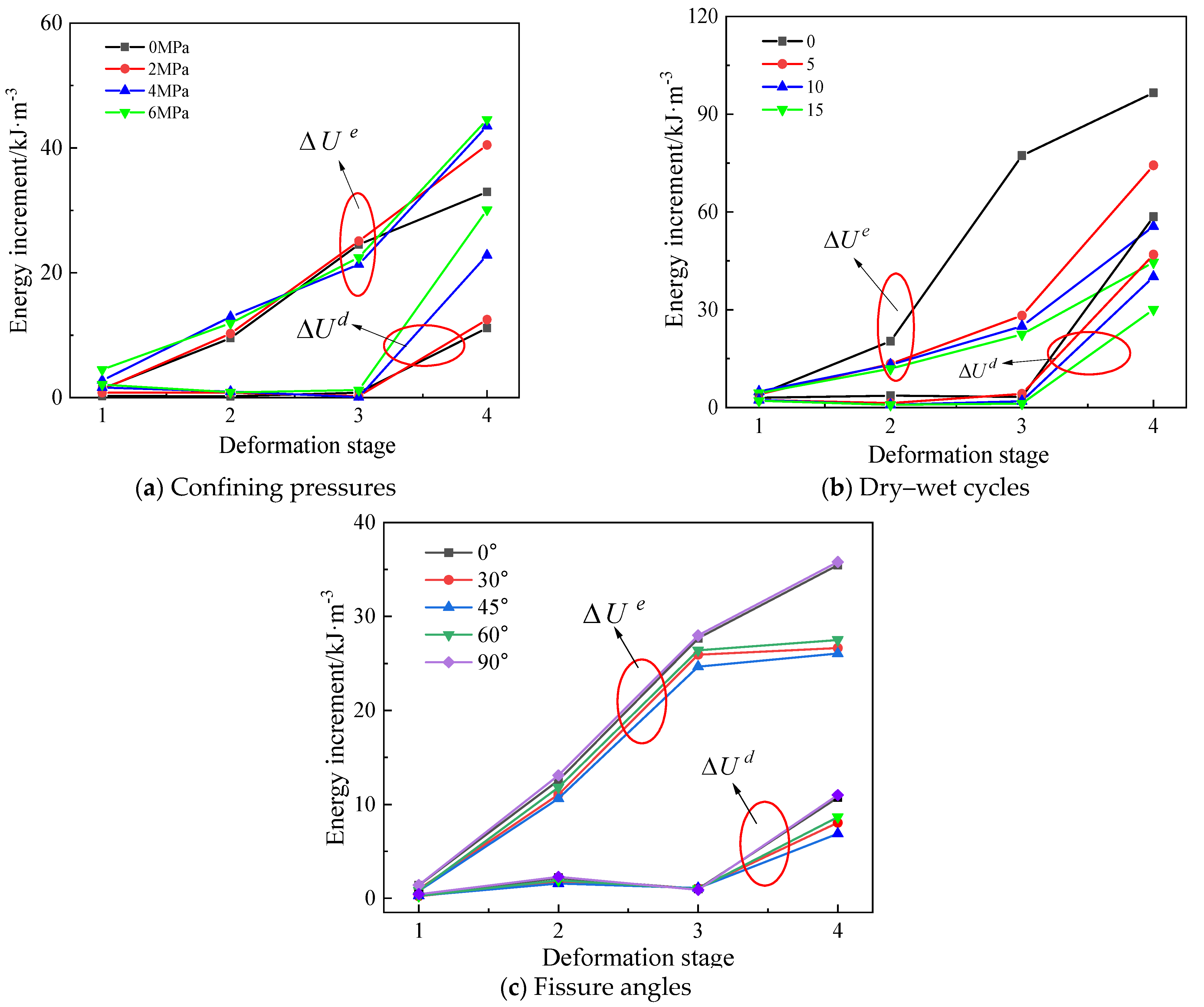

4.2. Analysis of Energy Distribution Law Before Peak

By analyzing the variation law of energy increment at each deformation stage and then determining the energy distribution law of rocks, the damage evolution characteristics and energy driving mechanism during the loading failure process of rocks can be effectively revealed.

Figure 9 shows the variation curves of energy increment and deformation stage before the peak under different conditions. In

Figure 9, the horizontal coordinates 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent the crack compaction stage, elasticity stage, crack stable propagation stage, and crack accelerated propagation stage, respectively.

As can be seen from

Figure 9, when the crack compaction stage progresses to the stage of accelerated crack propagation, the elastic energy increment of the specimen gradually increases under different conditions. The increment of dissipated energy remains nearly the same in the first three deformation stages but rises rapidly during the crack acceleration phase. It indicates that the proportion of dissipated energy in the first three deformation stages is very small, and the energy is mainly stored in the form of elastic energy, resulting in very little damage to the specimen. During the stage of accelerated crack propagation, the proportion of dissipated energy increases, and the damage to the specimen intensifies.

Further analysis of

Figure 9a shows that during the stage of accelerated crack propagation, as the confining pressure increases, the increment of elastic energy gradually increases, indicating that the confining pressure enhances the energy storage capacity of the specimen. As shown in

Figure 9b, during the last three deformation stages, the first five dry–wet cycles significantly affect the elastic energy increment, but the degradation effect diminishes after five cycles. The dissipated energy increment increases rapidly during the accelerated crack propagation stage. With the increase in the number of dry–wet cycles, the increment of elastic energy gradually decreases, indicating that dry–wet cycles reduce the energy storage capacity of rocks. As can be seen from

Figure 9c, with the increase in the fissure angle, the increment of elastic energy and the increment of dissipated energy first decrease and then increase, and are the smallest at a fissure angle of 45°. It indicates that the sample with a fissure angle of 45° stores the least energy and is prone to failure.

4.3. The Energy Criterion of Rock Failure

The elastic performance (energy storage limit) at the peak point can reflect the rock’s ability to resist failure. The closer the elastic performance of the rock is to the energy storage limit during the deformation process, the greater the risk of rock failure. However, crack damage stress represents a sign that a rock has reached its plastic yield strength. Therefore, the ratio of elastic energy at damage stress to that at peak stress is regarded as the energy storage level at damage stress (denoted by

(

)). The energy storage level at the damage stress can characterize the energy storage state of the rock, indirectly reflecting the relative stability of the loaded rock.

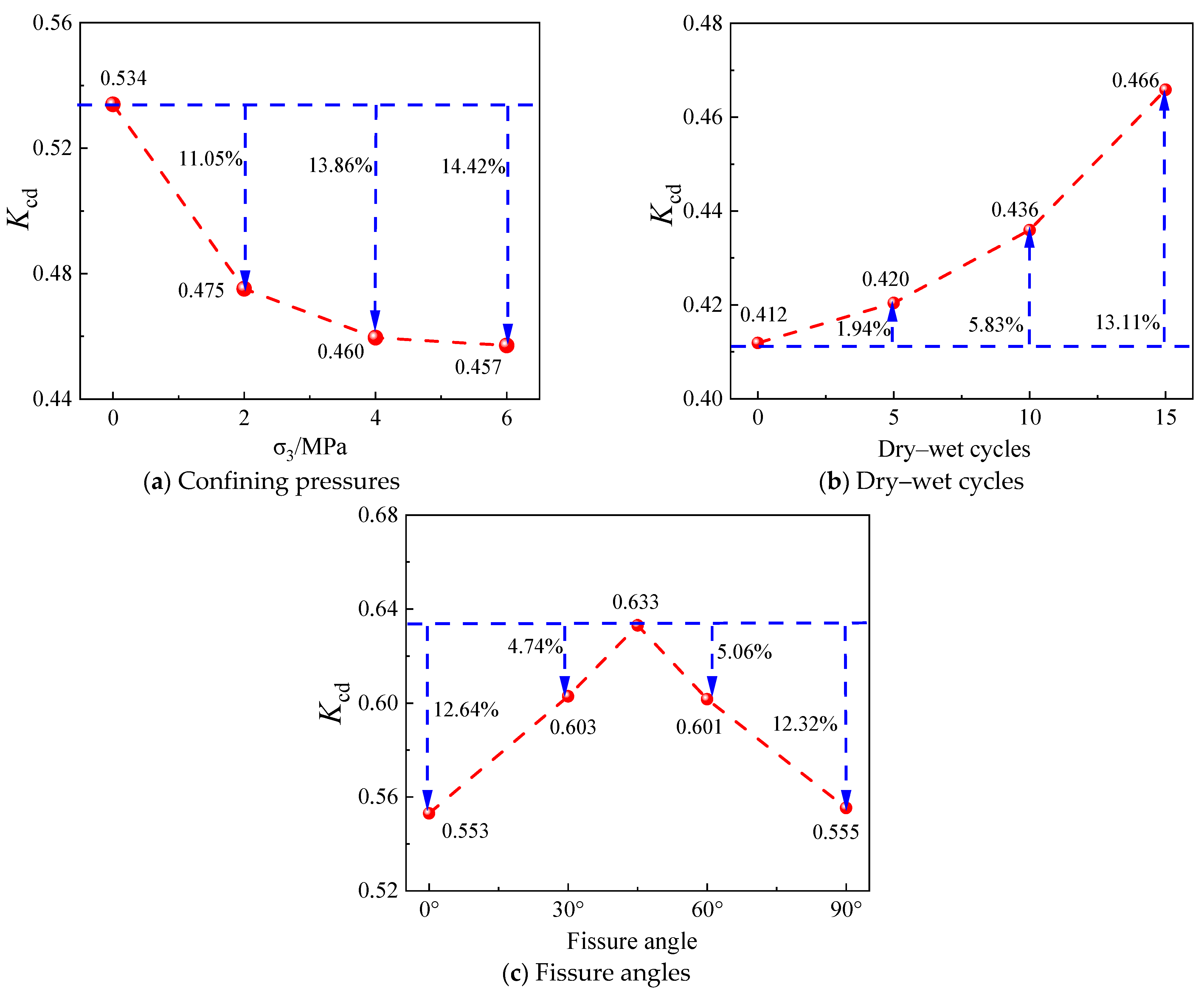

Figure 10 presents the relationship curve of

with confining pressure, dry–wet cycles, and fissure angle.

From

Figure 10a, it can be observed that as the confining pressure increases, K

cd gradually decreases, indicating an expanding gap between the stored energy and the energy storage limit. This leads to a longer time required to reach peak stress and increased difficulty in failure. Therefore, the increase in confining pressure reduces the risk of rock damage. As the number of dry–wet cycles increases, K

cd gradually increases, indicating that the closer the stored energy is to the energy storage limit, the more prone the rock is to damage (see

Figure 10b). With increasing fissure angle, K

cd first increases then gradually decreases, reaching its maximum at 45°. This indicates that samples with 45° cracks exhibit the highest energy storage capacity at damage stress, with stored energy approaching the storage limit, making them more prone to failure (see

Figure 10c).

5. Discussion

The long-term stability of geotechnical engineering depends on the degree of progressive damage and deterioration of rock. The experimental results show that the damage and deterioration of carbonaceous shale is the result of the combined effects of dry–wet cycles, confining pressure, and fissure angle. From the perspective of crack characteristic stress, the increase in confining pressure significantly enhances the crack characteristic stress, effectively suppressing the initiation and propagation of crack. The dry–wet cycle is regarded as a driving force for damage. Through the physical and chemical effects of water, it weakens mineral cementation, systematically reduces the characteristic stress of cracks at each stage, and accelerates the accumulation of damage. The anisotropic damage of rock is controlled by fissure angle. The crack characteristic stress of specimens with a 45° fissure angle is the smallest, and shear slip failure is the most likely to occur [

23].

From the perspective of energy evolution, the total energy and elastic energy storage capacity of rock are enhanced as confining pressure increases. The stability of rocks is improved. The initial damage of rock is promoted under dry–wet cycles, causing more energy to be converted into dissipated energy at the initial stage of loading and significantly weakening the elastic energy storage. The fissure angle has a quadratic function relationship with the energy index. When the fissure angle is 45°, the energy dissipates rapidly through the weak surface, the energy storage capacity is the weakest, and it is the most prone to instability.

Comprehensive analysis indicates that the dry–wet cycle, fissure angle, and confining pressure jointly determine the progressive damage and deterioration process of carbonaceous shale by regulating the characteristic stress and energy distribution mechanism of cracks.

6. Conclusions

The crack characteristic stress is enhanced with the increase in confining pressure, effectively suppressing the initiation and propagation of the crack. The dry–wet cycle is regarded as the driving force of damage, reducing the crack characteristic stress and promoting the damage of carbonaceous shale. The anisotropic damage of rock is controlled by fissure angle. The crack characteristic stress of specimens with a 45° fissure angle is the smallest.

The energy indexes of crack characteristic stress were increased with the increase in confining pressure, effectively improving the bearing capacity of carbonaceous shale. The energy indexes of crack characteristic stress was decreased by dry–wet damage. And the energy storage capacity of carbonaceous shale was weakened. The energy indexes of crack characteristic stress in carbonaceous shale with a 45° fissure angle are the smallest.

The energy storage level at the damage stress Kcd can be used as an early warning indicator for rock failure. The larger Kcd is, the more prone the rock is to failure. Kcd gradually decreases with the increase in confining pressure. Kcd gradually increases with the increase in the dry–wet cycles. With the increase in fissure angle, Kcd first increases and then decreases, reaching the maximum at a fissure angle of 45°.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and S.L.; methodology, Y.L.; validation, Y.L.; formal analysis, X.L. and A.J.; investigation, X.L. and D.C.; resources, Y.L. and S.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and S.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52108405) and the Excellent Youth Project of Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 24B0675).

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials support our published claims and comply with field standards. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

References

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Xu, Z. Research on creep model carbonaceous shale under freeze-thaw cycle. China J. Highw. Transp. 2019, 32, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, W. Study on mechanical properties and energy characteristics of carbonaceous shale with different fissure angles under dry-wet cycles. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, L.; Peng, R. Energy Analysis and Criteria for Structural Failure of Rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2009, 1, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cai, X.; Ma, D.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Tan, L. Dynamic tensile properties of sandstone subjected to wetting and drying cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, K.; Peng, J.; Hou, D. Experimental investigation of cyclic wetting-drying effect on mechanical behavior of a medium-grained sandstone. Eng. Geol. 2021, 293, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Liu, H.; Gao, X.; Huang, D.; Zhang, W. Influence of cyclic wetting-drying on the shear strength of limestone with a soft interlayer. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2021, 54, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, D.; Lei, S.; Lu, J.; Xiao, H.; Li, J.; Li, H. Mechanical and microstructural properties of schist exposed to freeze-thaw cycles, dry-wet cycles, and alternating actions. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2025, 35, 783–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.; Fan, Z. Research on mechanical properties and strength criterion of carbonaceous shale with pre-existing fissures under drying-wetting cycles. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2022, 41, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Tang, X.; Yin, H.; Qin, Y.; Guo, Z.; Fang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y. Investigating the impact of the quantity of wet and dry cycles on the mechanical characteristics and fracture variations of sandstones. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Jiang, T.; Wu, Q.; Dong, J.; Yu, Z. Critical slowing down characteristics of acoustic emission for fracture instability of sandstone down-slope rock bridge under cyclic wetting and drying. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 131, 104372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Wang, H.; Fu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, X. Mechanical and acoustic responses of sandstone with varying particle sizes under wet–dry cycles. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2025, 43, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Yao, Q.; Cao, S.; Zheng, C.; Xu, Q.; Xia, Z.; Shang, X.; Huang, G. Analysis of cracks development and damage evolution in red sandstone under dry-wet cycles based on temporal and frequency characteristics of acoustic emission. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.; Wu, F.; Ren, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, C. Effect of dynamic disturbances and dry-wet cycles on the degradation law and acoustic emission evolution characteristics of argillaceous sandstone: An experimental study. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 241, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Deng, J.; Huang, Y.; He, Z. Influence of water on the fracture process of marble with acoustic emission monitoring. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 3239–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Tang, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, S. Characteristic stress response law and fracture precursor of granite under different dynamic disturbance damage conditions. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Wu, R. Full-field strain evolution and characteristic stress levels of rocks containing a single pre-existing flaw under uniaxial compression. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 3145–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Yi, Q.; Jivkov, P.; Bian, Z.; Chen, W.; Wu, J. Effect of dry-wet cycles on dynamic properties and microstructures of sandstone: Experiments and modelling. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 655–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, P.; Ji, P.; Sun, L.; Pan, Y. Case study on the failure characteristics and energy evolution of three types of hole-fissured sandstone under wetting–drying cycles. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Du, B.; Cheng, Q. Dynamic tensile failure characteristics and energy dissipation of red sandstone under dry–wet cycles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Peng, R.; Ju, Y.; Zhou, H. On energy analysis of rock failure. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2005, 24, 2603–2608. [Google Scholar]

- You, M.; Su, C. Experimental study on strengthening of marble specimen in cyclic loading of uniaxial or pseudo–triaxial compression. Chin. J. Solid Mech. 2009, 29, 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 23561.5-2009; Methods for Determining the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Coal and Rock. China Quality and Standards Publishing & Media Co. Led.: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, Z.; Li, S.; Dong, P. Energy evolution and failure characteristics of single fissure carbonaceous shale under drying-wetting cycles. Rock Soil Mech. 2022, 43, 1761–1771. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Li, J.; Ren, F.; Liu, D. Experimental investigation on rockburst ejection velocity of unidirectional double-face unloading of sandstone with different bedding angles. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2021, 40, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).