Study on the Fracture Characteristics and Mechanisms of Iron Ore Under Dynamic Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

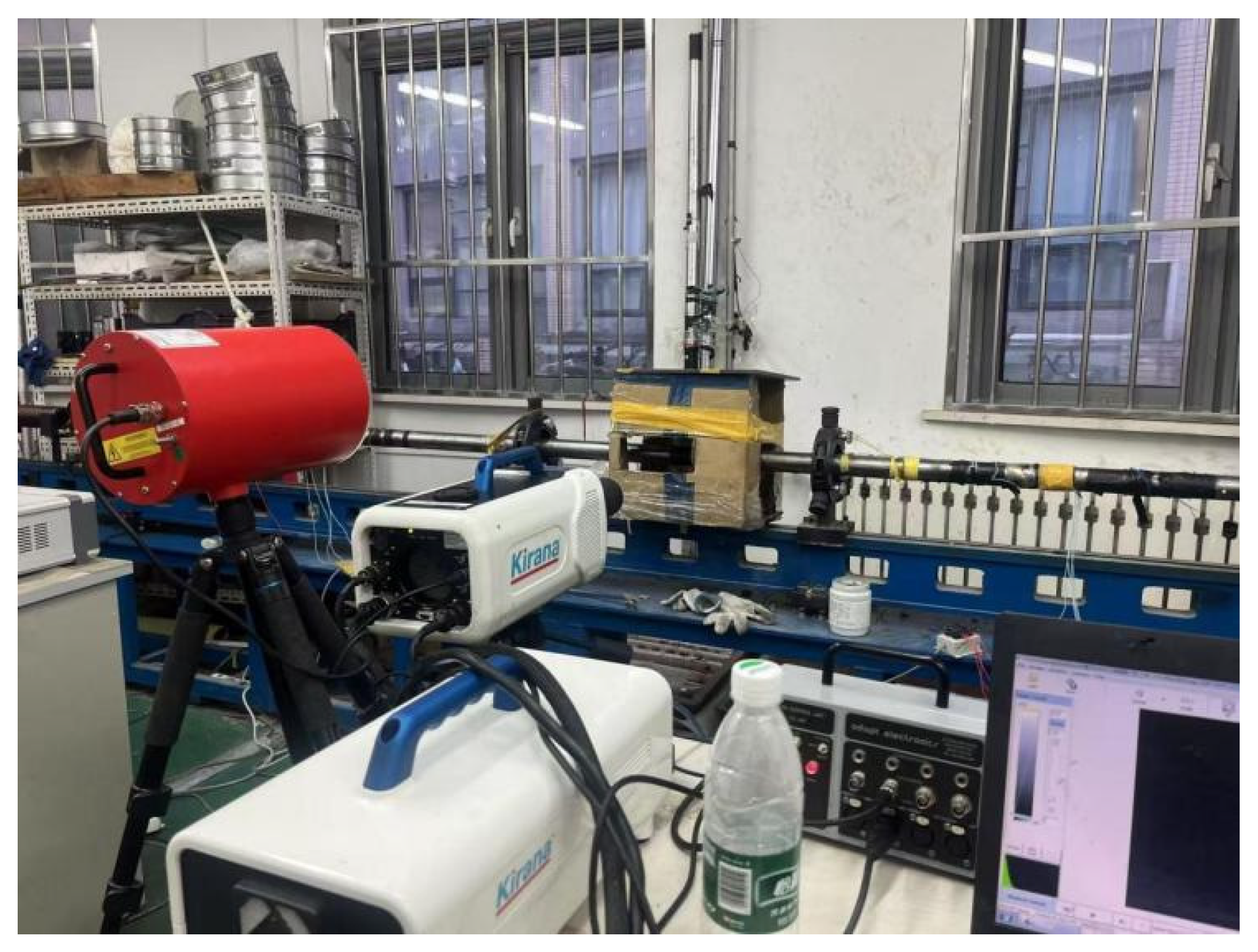

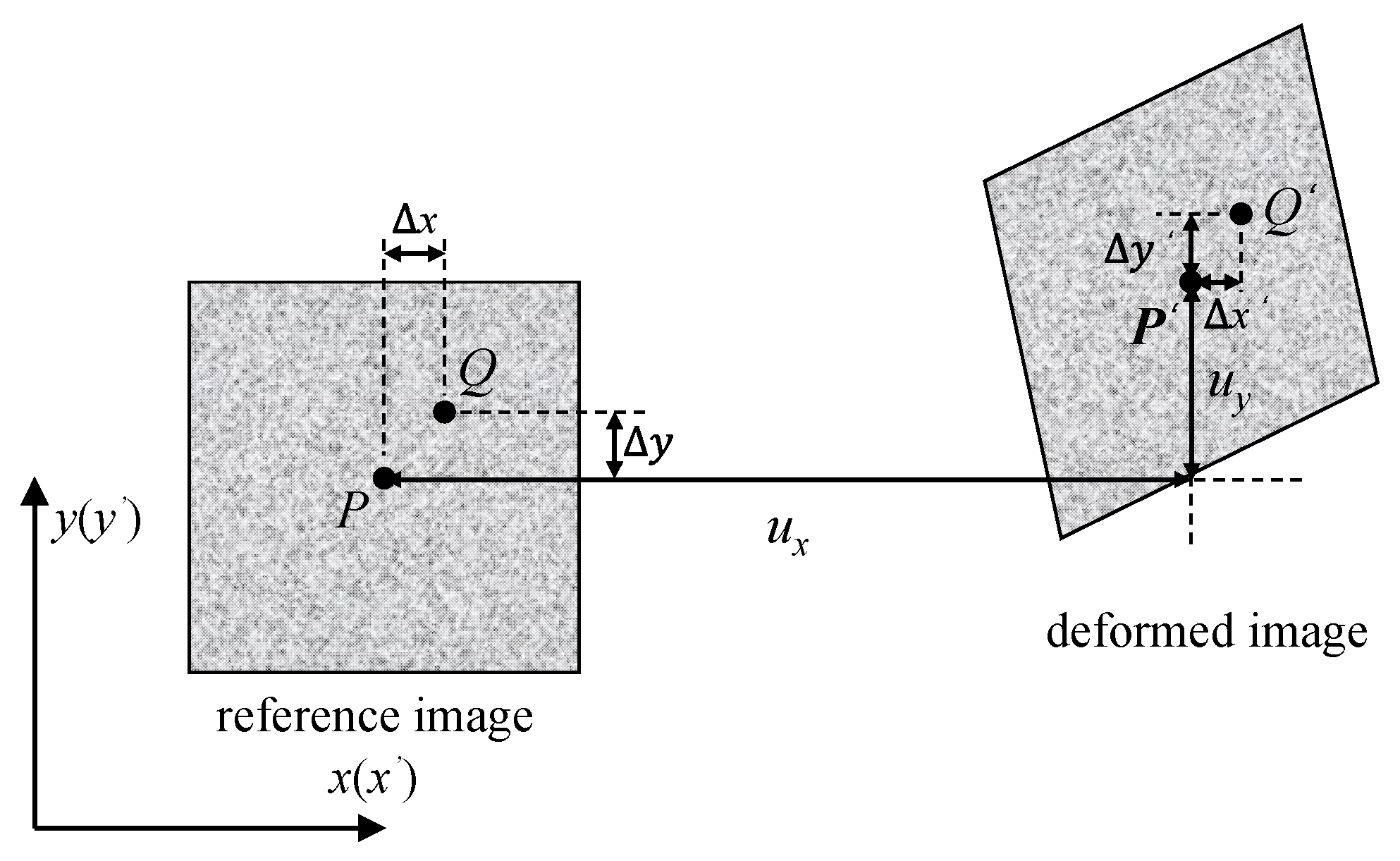

2.1. Experimental Setup and Fundamental Principles

2.2. Specimen Preparation

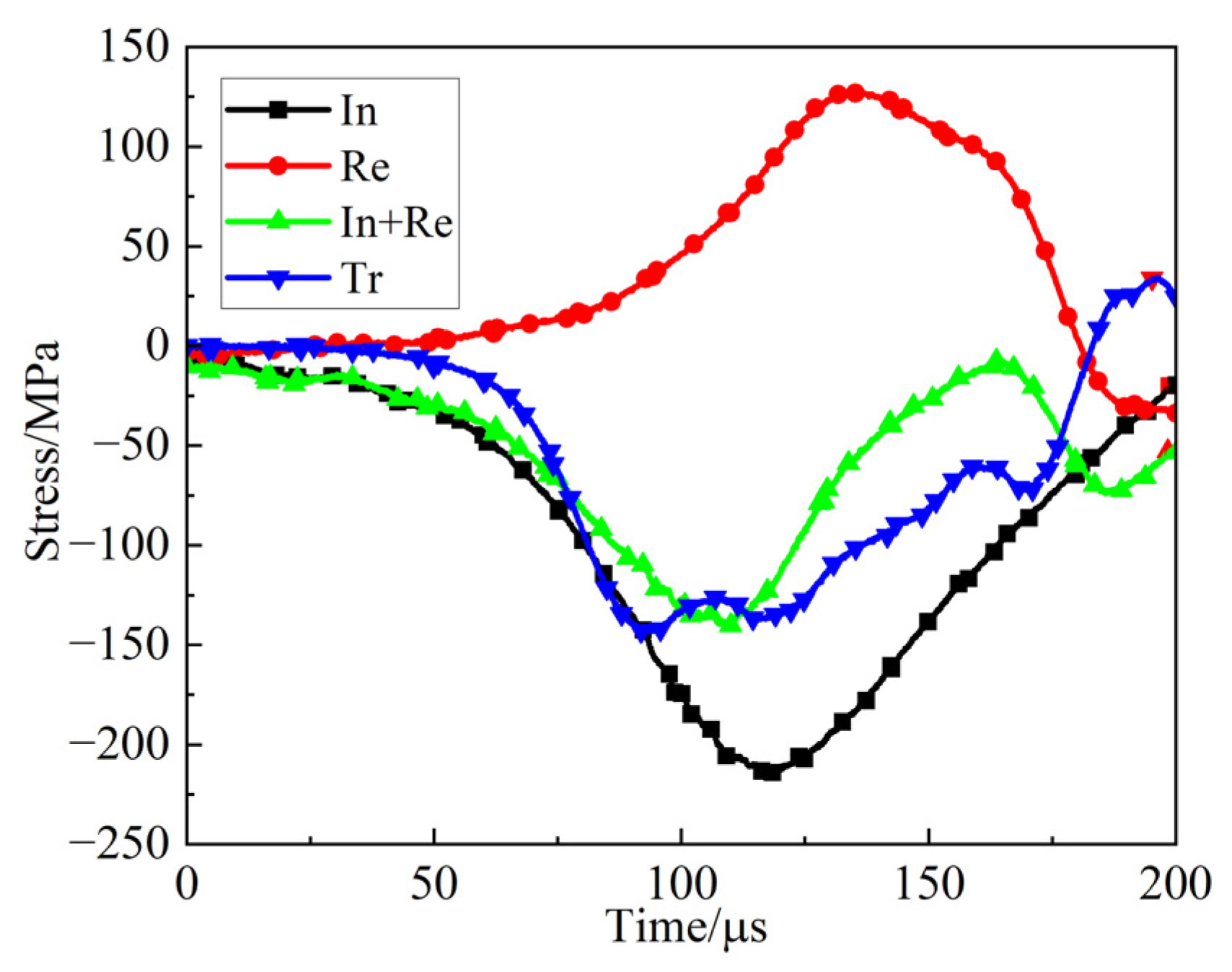

2.3. Verification of Dynamic Stress Equilibrium

3. Results

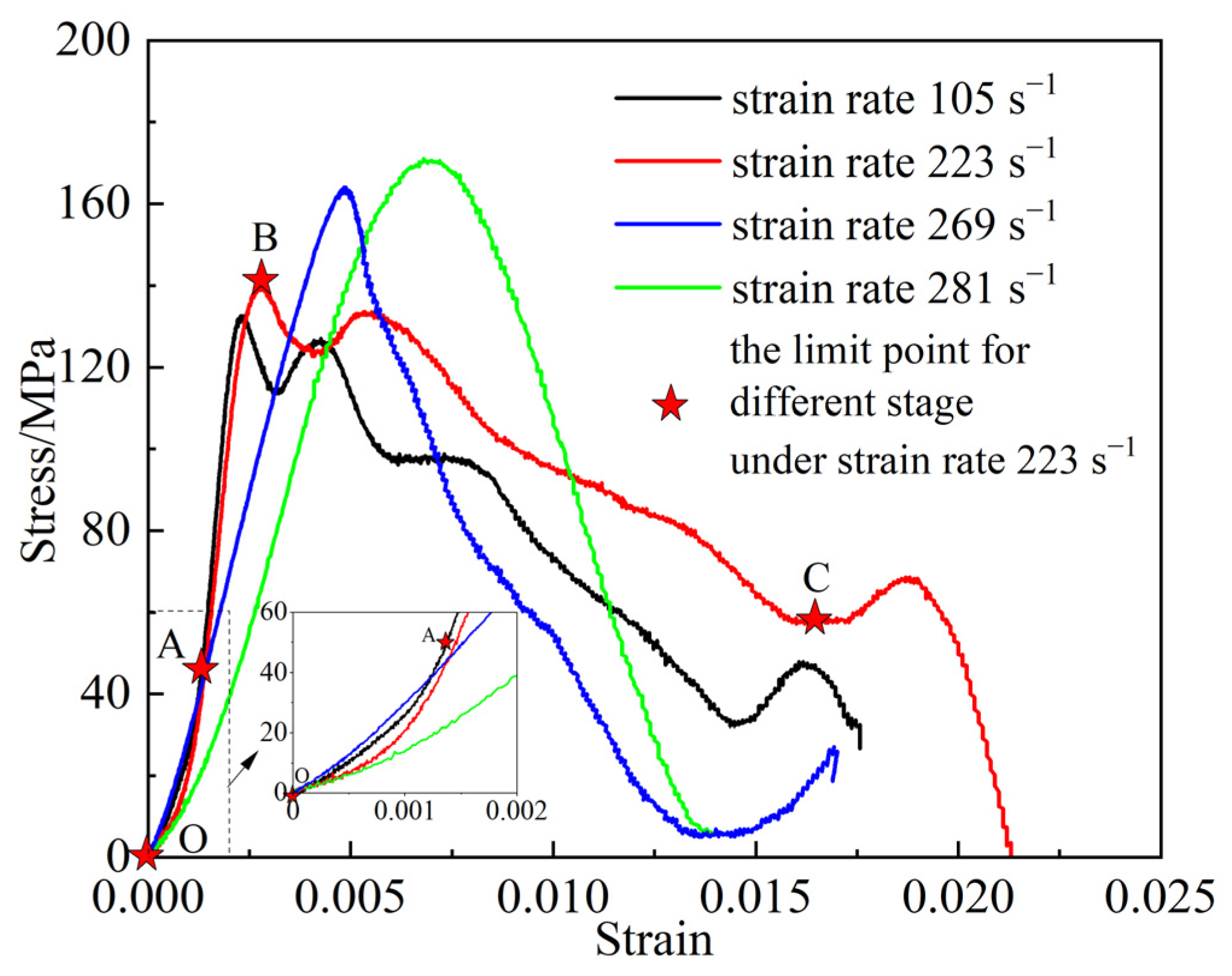

3.1. Dynamic Constitutive Relationship of Iron Ore

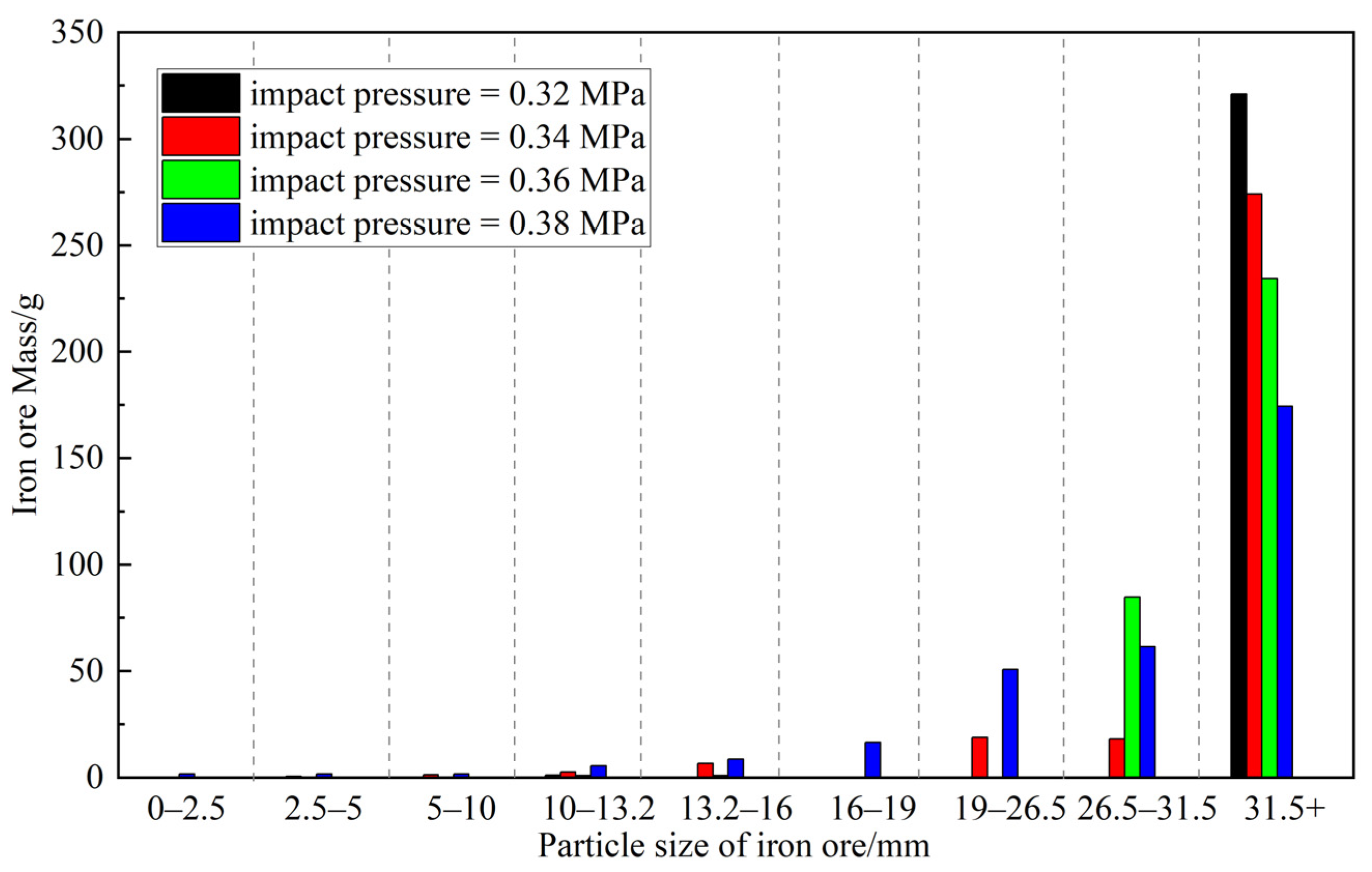

3.2. Analysis of Ore Fragmentation Characteristics

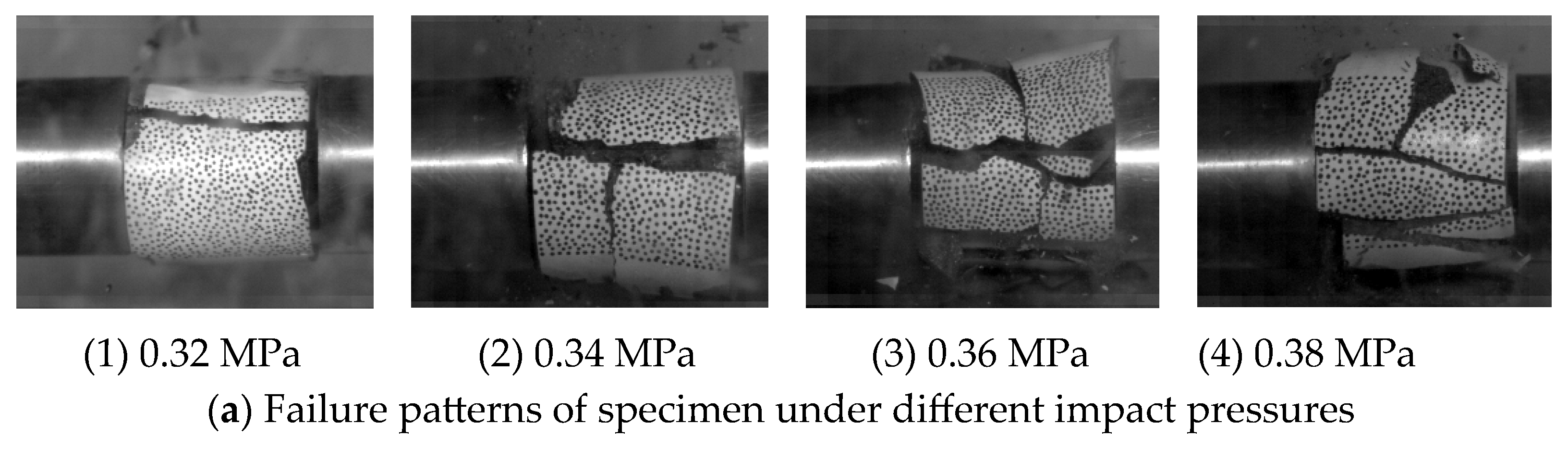

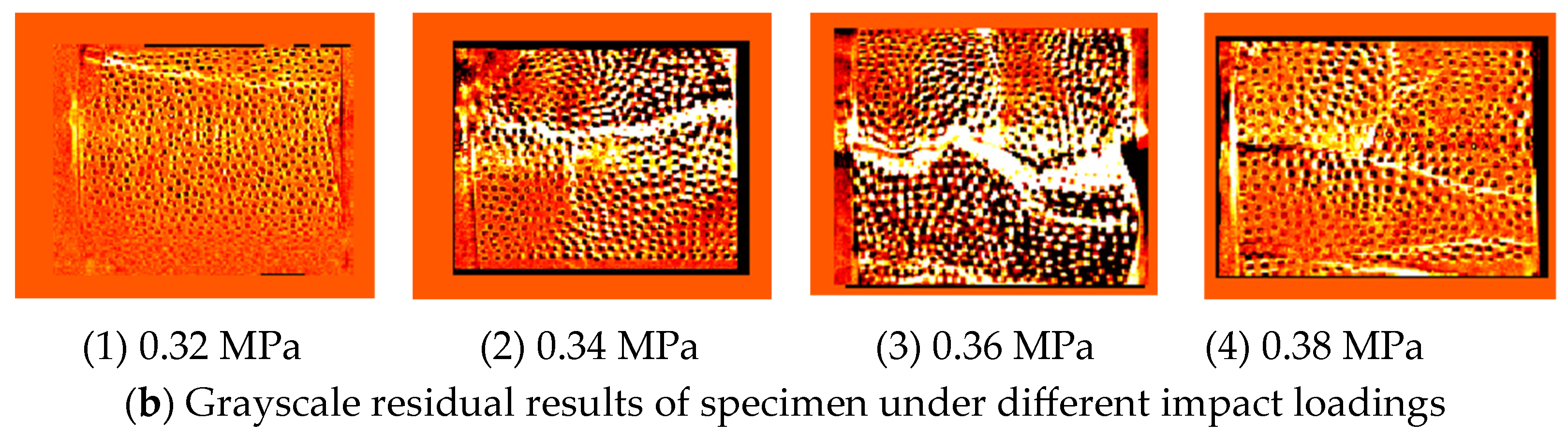

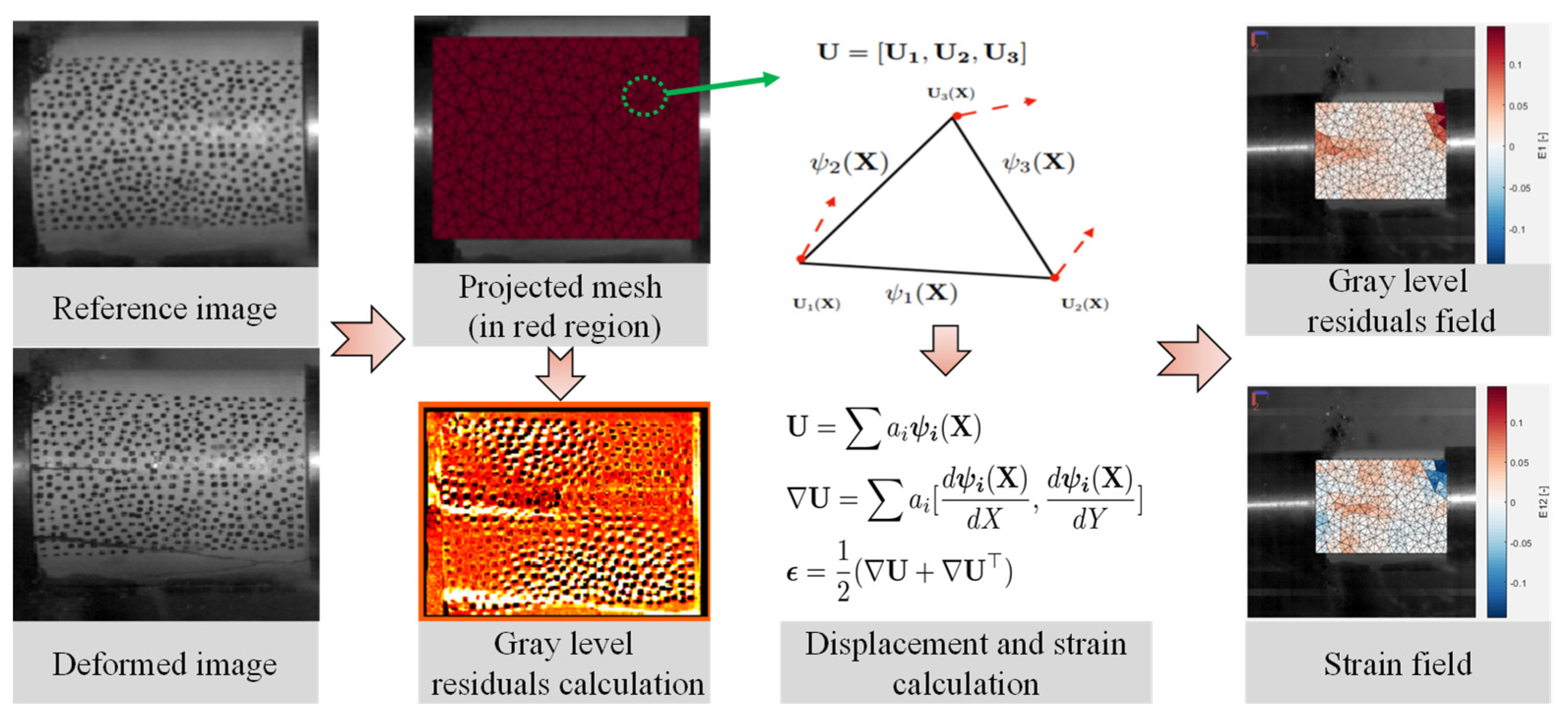

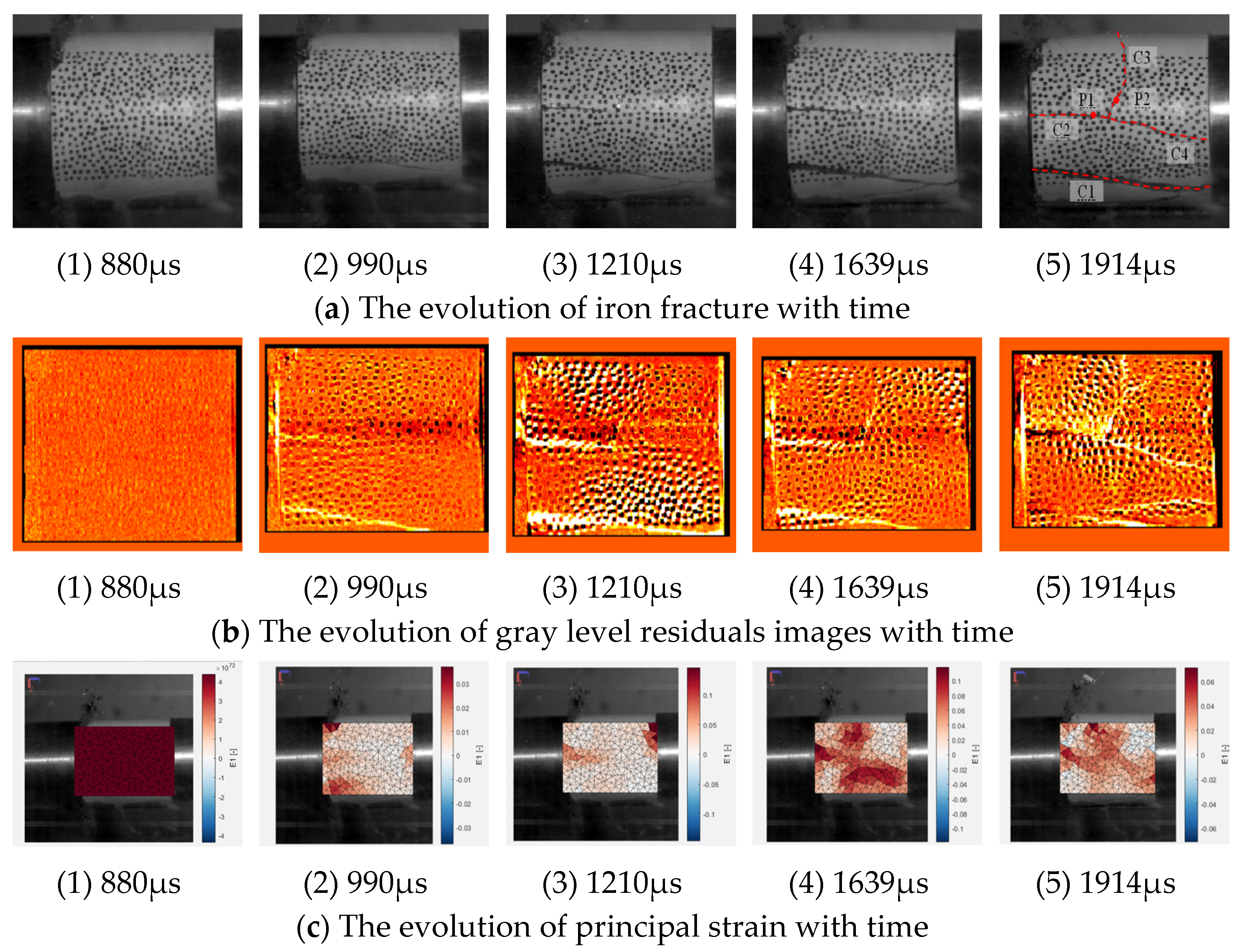

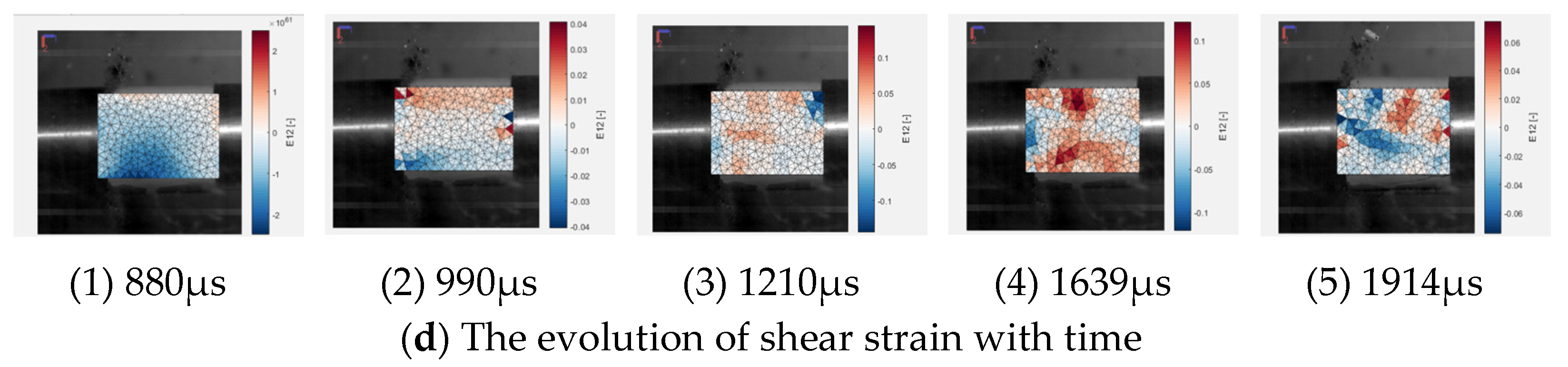

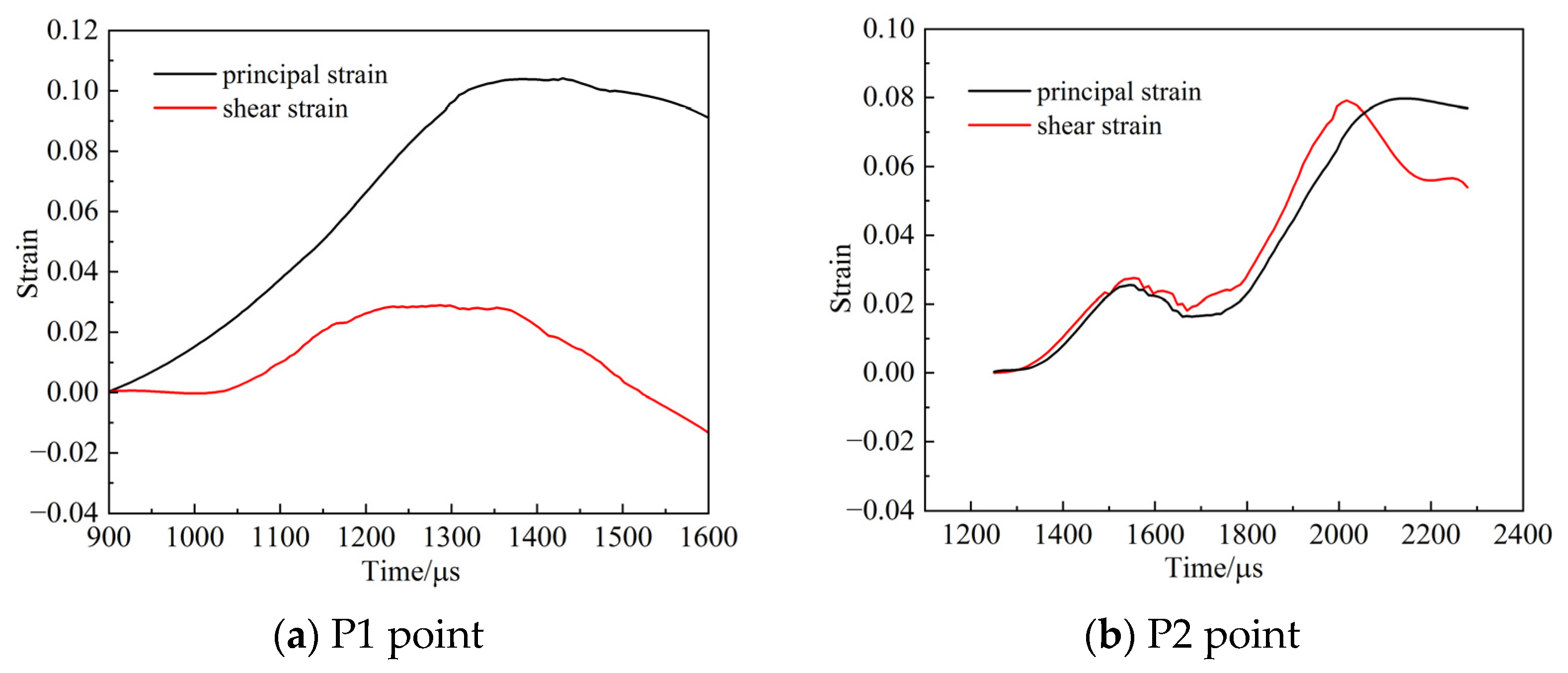

3.3. Analysis of the Specimen Fracture Process

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under low strain rates, the dynamic stress–strain curve of iron ore sequentially exhibits compaction, elastic, and failure stages during loading. However, as the strain rate increases, the compaction stage gradually diminishes.

- (2)

- With an increase in impact air pressure, the strain rate of iron ore gradually rises, the elastic modulus decreases, and the failure strength increases, resulting in enhanced toughness of the ore and greater resistance to failure.

- (3)

- As the impact loading increases, the failure of iron ore increased gradually. However, there exists a critical impact load, beyond which the amount of small fragments visibly increases, whereas the proportion of large fragments decreases only marginally.

- (4)

- Under impact loading, tensile cracks initially develop and propagate along the loading direction in the ore. However, as the impact air pressure increases, the shear strain field within the ore gradually expands, leading to an increase in tensile–shear failures. This causes the specimen to break into multiple fragments, progressively increasing the degree of ore fragmentation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Hu, X.; He, X.; Liu, J.; Liang, C.; Lim, M.K. Deciphering iron ore trade dynamics: Supply disruption risk propagation in global networks through an improved cascading failure model. Resour. Policy 2024, 95, 105157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jégourel, Y. The global iron ore market: From cyclical developments to potential structural changes. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Vakylabad, A.B.; Hassanzadeh, A.; Niedoba, T.; Surowiak, A. An evaluation on the impact of ore fragmented by blasting on mining performance. Minerals 2022, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaee, N.H.; Sargheyni, J.; Pezeshkan, M.; Kianoush, P. Design and optimization of a spiral separator for enhanced chromite recovery and sustainability. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 100880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; An, H. Fractal characteristics and energy dissipation of granite after high-temperature treatment based on SHPB experiment. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 861847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, M.Q.; Asadi, P.; Ashrafi, M.J.; Fakhimi, A. Strength, energy consumption, particle size distribution and fracture toughness in rock fragmentation under dynamic loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 324, 111237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Zhou, Z.L.; Yin, T.B.; Liao, G.Y.; Ye, Z.Y. Energy consumption in rock fragmentation at intermediate strain rate. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2009, 16, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Jia, H.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Luo, S. Energy dissipation and particle size distribution of granite under different incident energies in SHPB compression tests. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 8899355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Ye, Z.; Liu, K. Obtaining constitutive relationship for rate-dependent rock in SHPB tests. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 43, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ma, H.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J.; Yang, J.; Bao, W. Dynamic mechanical behaviors and failure mechanism of lignite under SHPB compression test. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dai, F. Dynamic response and failure mechanism of brittle rocks under combined compression-shear loading experiments. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Dai, F.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wei, M.D. Dynamic mechanical response and failure behavior of single-flawed rocks under combined compression-shear loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 314, 110777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Han, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, X. Dynamic mechanical properties and fracturing behavior of marble specimens containing single and double flaws in SHPB tests. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1623–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Sanchidrián, J.A.; Ouchterlony, F.; Luukkanen, S. Reduction of fragment size from mining to mineral processing: A review. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 747–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoult, N.A.; Take, W.A.; Lee, C.; Dutton, M. Experimental accuracy of two dimensional strain measurements using digital image correlation. Eng. Struct. 2013, 46, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, B.P.; Gandhi, V.; Ravichandran, G. An Internal Digital Image Correlation Technique for High-Strain Rate Dynamic Experiments. Exp. Mech. 2025, 65, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Fu, Y. Development and Application of Dynamic Integrated DIC Material Parameters Inversion Method for SHPB Tests. Exp. Mech. 2024, 64, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.C. Behaviour of foam concrete under impact loading based on SHPB experiments. Shock Vib. 2019, 2019, 2065845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Li, M.; Pu, H.; Ju, F.; Zhang, K.; Wu, H. Experimental study on dynamic mechanical characteristics of coal specimens considering initial damage effect of cyclic loading. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 2123–2137. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Leclerc, H.; Neggers, J.; Mathieu, F.; Roux, S.; Hild, F. Correli 3.0; Agence pour la Protection des Programmes: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X.; Gourrierec, C.L.; Roux, H.S. Brightness and contrast corrections for stereo correlation Global and instantaneous formulation with spatial regularization. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (kg/m3) | Longitudinal Wave Velocity (m/s) | Shear Wave Velocity (m/s) | Uniaxial Compressive Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3460 | 3846 | 1923 | 96.14 | 47.64 | 0.22 |

| Stages | Characteristics | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Compaction Stage | The stress increases slowly with the increase in strain | The internal defects of the specimen, such as pores and voids, rapidly closed under impact loading |

| Elastic Stage | The stress increases approximately linearly with the increase in strain | Micro-cracks began to initiate, and rock damage accumulated gradually |

| Failure Stage | The stress dropped rapidly with the increase in strain | Macroscopic cracks generated, leading to the production of iron ore fragment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.; Xu, P.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Y.; Chang, X.; Lin, Z. Study on the Fracture Characteristics and Mechanisms of Iron Ore Under Dynamic Loading. Processes 2025, 13, 3436. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113436

Tian Y, Xu P, Li H, Li J, Zhou S, Chen Y, Chang X, Lin Z. Study on the Fracture Characteristics and Mechanisms of Iron Ore Under Dynamic Loading. Processes. 2025; 13(11):3436. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113436

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Yilin, Peng Xu, Hua Li, Junjie Li, Shiqing Zhou, Yanting Chen, Xuyang Chang, and Zhibo Lin. 2025. "Study on the Fracture Characteristics and Mechanisms of Iron Ore Under Dynamic Loading" Processes 13, no. 11: 3436. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113436

APA StyleTian, Y., Xu, P., Li, H., Li, J., Zhou, S., Chen, Y., Chang, X., & Lin, Z. (2025). Study on the Fracture Characteristics and Mechanisms of Iron Ore Under Dynamic Loading. Processes, 13(11), 3436. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13113436