From Failures to Insights: The Role of Surge Tanks in Integrated and Continuous Bioprocessing for Antibody Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

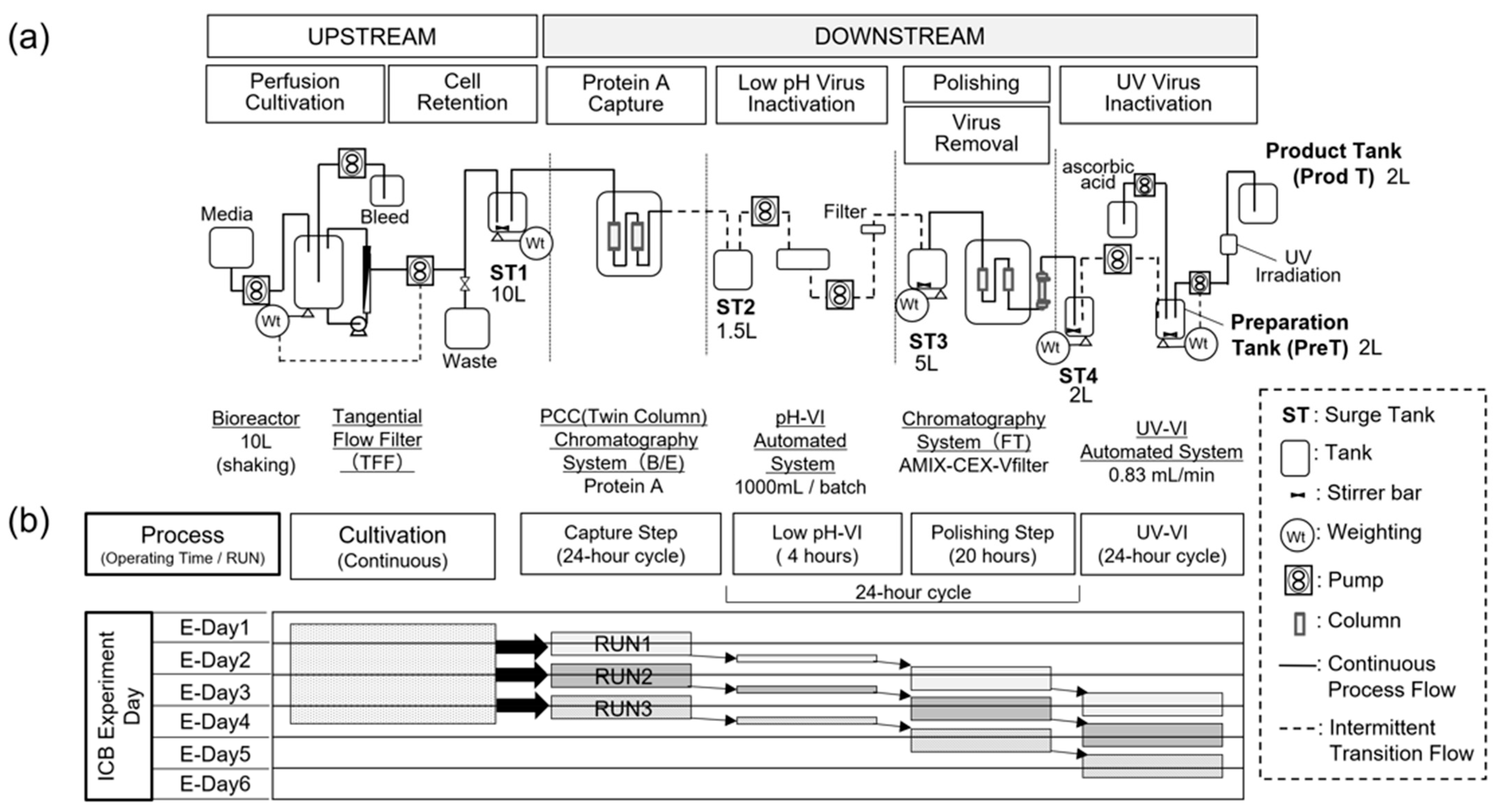

2.1. Experimental Design of Pilot-Scale ICB

2.2. Upstream Operations

2.3. Downstream Operations

2.3.1. Capture Chromatography (Capture Step)

2.3.2. Low-pH Virus Inactivation (Low-pH-VI)

2.3.3. Polishing Chromatography and Virus Removal (Polishing Step)

2.3.4. Continuous Virus Inactivation Using UV Radiation (UV-VI)

2.4. Setup of Surge Tanks and Integration of Unit Operations

3. Results

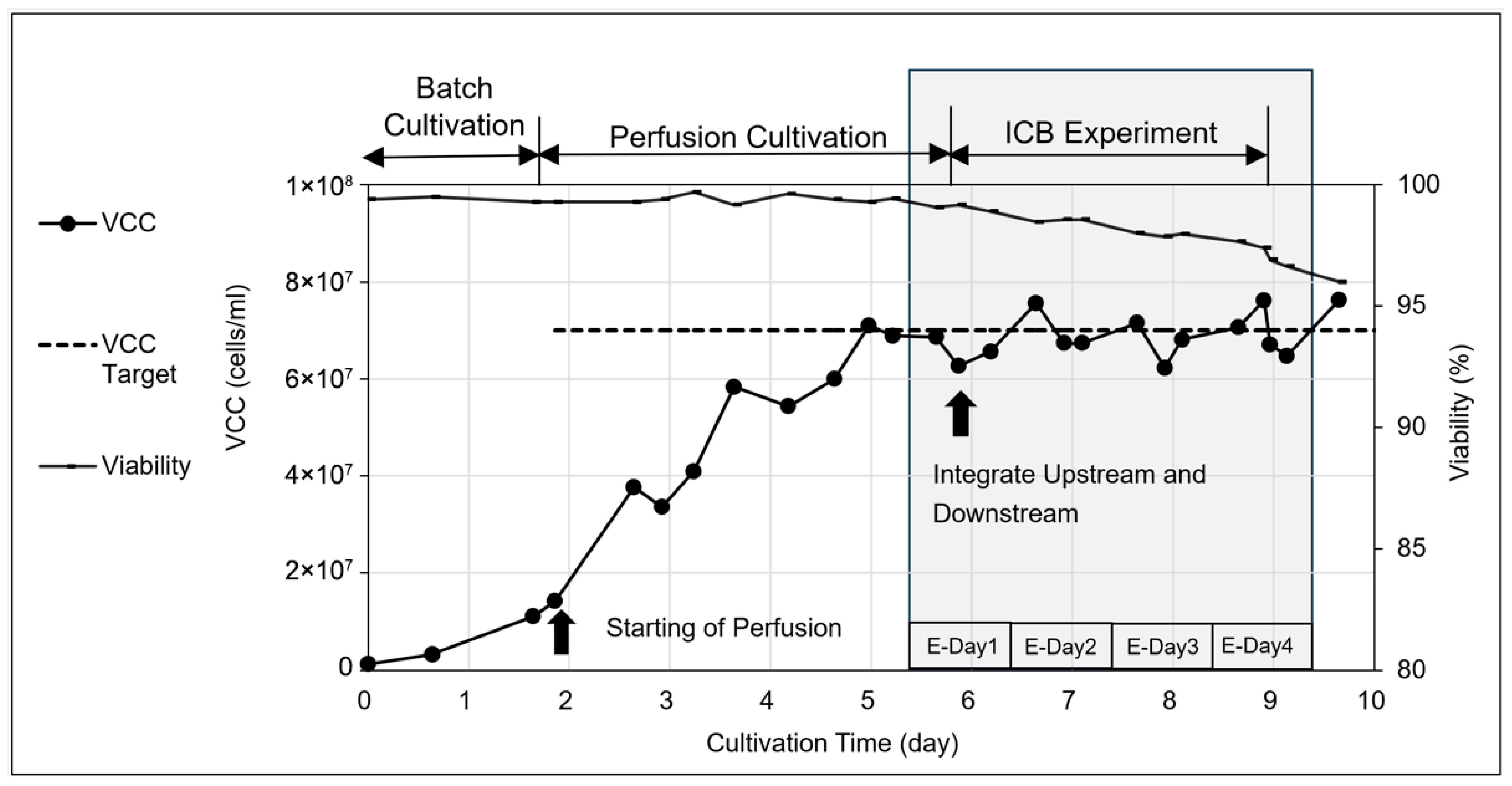

3.1. Cultivation Process

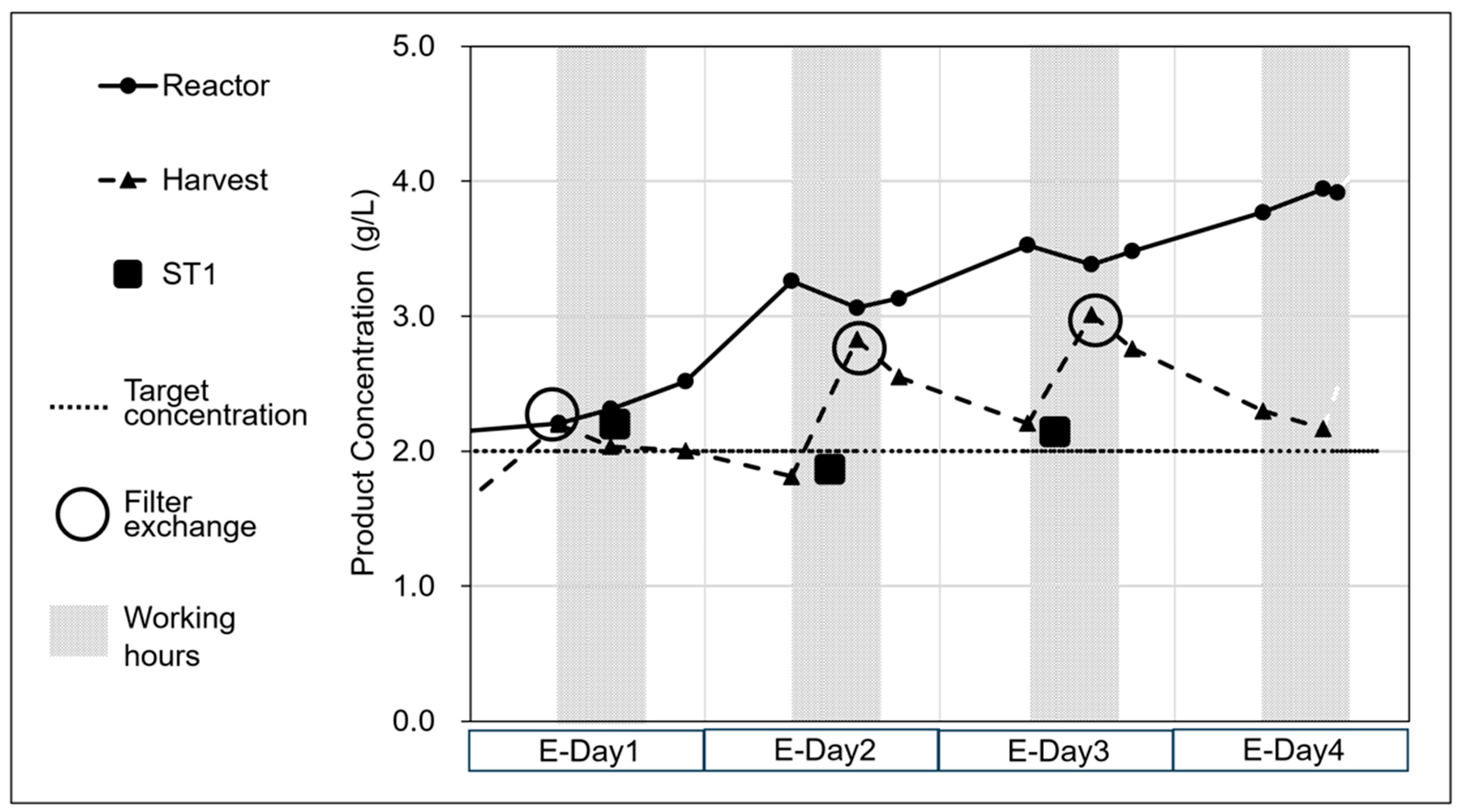

3.2. Integration of the Upstream and Downstream Through ST1

3.3. Storage Downstream: ST2, ST3, and ST4

4. Discussion

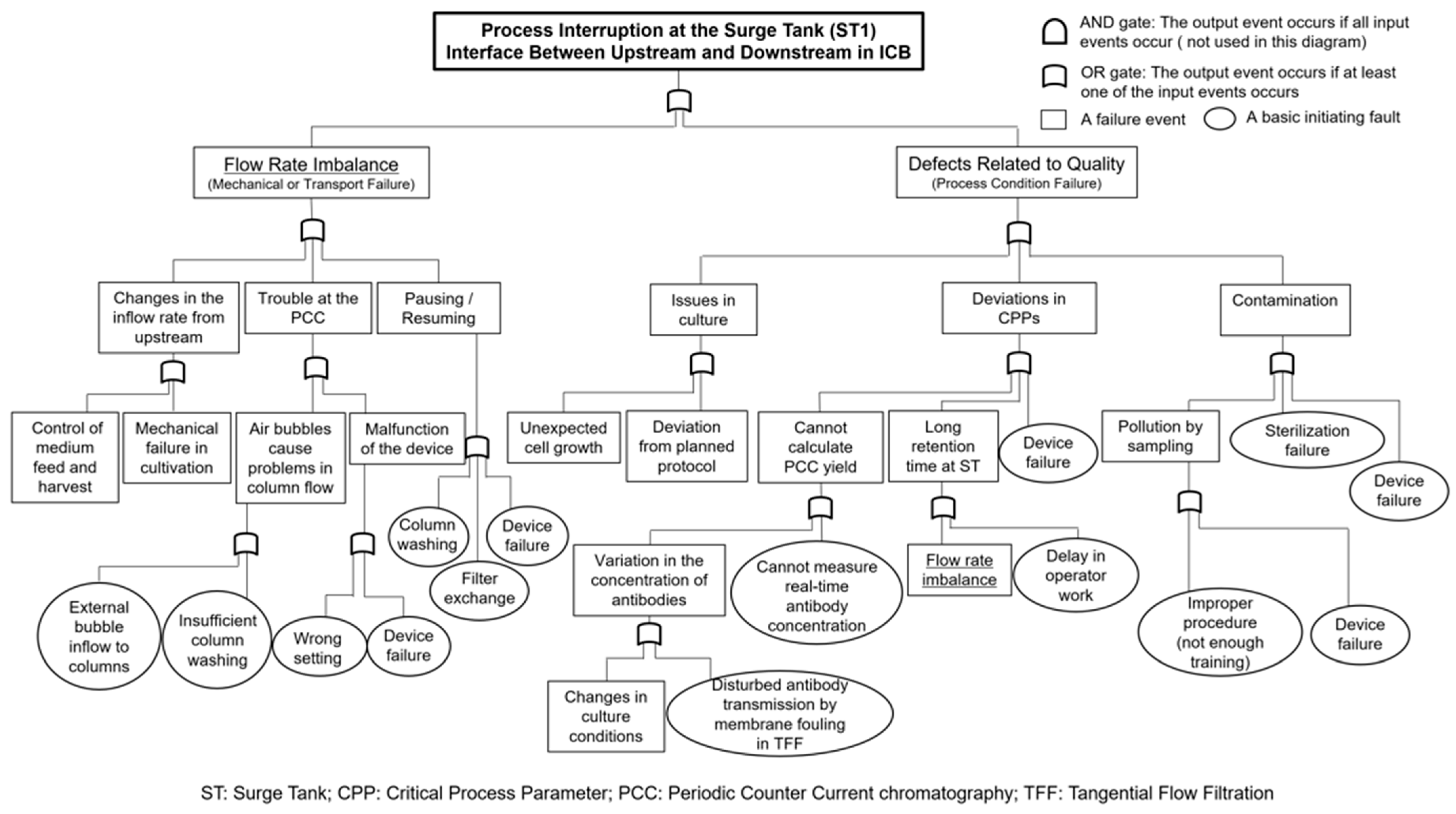

4.1. Visualizing Surge Tank Failure Events

4.2. Considerations Associated with the Surge Tanks in ICB

4.2.1. Control Perspective

4.2.2. Dimension Perspective

4.2.3. Function Perspective

4.2.4. Practical Application Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erickson, J.; Baker, J.; Barrett, S.; Brady, C.; Brower, M.; Carbonell, R.; Charlebois, T.; Coffman, J.; Connell-Crowley, L.; Coolbaugh, M.; et al. End-to-End Collaboration to Transform Biopharmaceutical Development and Manufacturing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 3302–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, J.; Coffman, J.; Ho, S.V.; Farid, S.S. Integrated Continuous Bioprocessing: Economic, Operational, and Environmental Feasibility for Clinical and Commercial Antibody Manufacture. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, O.; Qadan, M.; Ierapetritou, M. Economic Analysis of Batch and Continuous Biopharmaceutical Antibody Production: A Review. J. Pharm. Innov. 2019, 14, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, H.; Branton, H.; Farid, S.S. End-to-End Continuous Bioprocessing: Impact on Facility Design, Cost of Goods, and Cost of Development for Monoclonal Antibodies. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 3468–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Ardeshna, H.; Gillespie, C.; Ierapetritou, M. Process Design of a Fully Integrated Continuous Biopharmaceutical Process Using Economic and Ecological Impact Assessment. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2022, 119, 3567–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerzon, G.; Sheng, Y.; Kirkitadze, M. Process Analytical Technologies—Advances in Bioprocess Integration and Future Perspectives. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 207, 114379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Fernandez, J.; Vellala, P.; Kulkarni, T.A.; Aguilar, I.; Ritz, D.; Lan, K.; Patel, P.; et al. A Fully Integrated Online Platform For Real Time Monitoring Of Multiple Product Quality Attributes In Biopharmaceutical Processes For Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornecki, M.; Strube, J. Process Analytical Technology for Advanced Process Control in Biologics Manufacturing with the Aid of Macroscopic Kinetic Modeling. Bioengineering 2018, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Helgers, H.; Lohmann, L.J.; Vetter, F.; Juckers, A.; Mouellef, M.; Zobel-Roos, S.; Strube, J. Process Analytical Technology as Key-Enabler for Digital Twins in Continuous Biomanufacturing. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 2336–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L.; O’Connor, T.F.; Yang, X.; Cruz, C.N.; Chatterjee, S.; Madurawe, R.D.; Moore, C.M.V.; Yu, L.X.; Woodcock, J. Modernizing Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: From Batch to Continuous Production. J. Pharm. Innov. 2015, 10, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Guideline Q13 on Continuous Manufacturing of Drug Substances and Drug Products; International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov, K.; Conney, C. White Paper on Continuous Bioprocessing. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 104, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, J.; Brower, M.; Connell-Crowley, L.; Deldari, S.; Farid, S.S.; Horowski, B.; Patil, U.; Pollard, D.; Qadan, M.; Rose, S.; et al. A Common Framework for Integrated and Continuous Biomanufacturing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1721–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karst, D.J.; Serra, E.; Villiger, T.K.; Soos, M.; Morbidelli, M. Characterization and Comparison of ATF and TFF in Stirred Bioreactors for Continuous Mammalian Cell Culture Processes. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 110, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, O.; Lenhoff, A.M. Developments and Opportunities in Continuous Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing. MAbs 2021, 13, 1903664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaki, A.; Namatame, T.; Nakaya, M.; Omasa, T. Model-Based Control System Design to Manage Process Parameters in Mammalian Cell Culture for Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.S.; Kateja, N.; Kumar, D. ScienceDirect Process Integration and Control in Continuous Bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2018, 22, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konoike, F.; Taniguchi, M.; Yamamoto, S. Integrated Continuous Downstream Process of Monoclonal Antibody Developed by Converting the Batch Platform Process Based on the Process Characterization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2024, 121, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, M.A.; Nöbel, M.; Roche Recinos, D.; Martínez, V.S.; Schulz, B.L.; Howard, C.B.; Baker, K.; Shave, E.; Lee, Y.Y.; Marcellin, E.; et al. Perfusion Culture of Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells for Bioprocessing Applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2022, 42, 1099–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Udugama, I.A.; Gargalo, C.L.; Gernaey, K.V. Why Is Batch Processing Still Dominating the Biologics Landscape? Towards an Integrated Continuous Bioprocessing Alternative. Processes 2020, 8, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, H.; Sponchioni, M.; Morbidelli, M. Integration and Digitalization in the Manufacturing of Therapeutic Proteins. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 248, 117159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.C.; Kamga, M.H.; Agarabi, C.; Brorson, K.; Lee, S.L.; Yoon, S. The Current Scientific and Regulatory Landscape in Advancing Integrated Continuous Biopharmaceutical Manufacturing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopda, V.; Gyorgypal, A.; Yang, O.; Singh, R.; Ramachandran, R.; Zhang, H.; Tsilomelekis, G.; Chundawat, S.P.S.; Ierapetritou, M.G. Recent Advances in Integrated Process Analytical Techniques, Modeling, and Control Strategies to Enable Continuous Biomanufacturing of Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 2317–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grampp, G.; Bosley, A.; Qadan, M.; Schiel, J.; Spasoff, A.; Valax, P.; Schaefer, G. Managing Integrated Continuous Bioprocesses in Real Time: Deviations in Product Quality. Biotechnol. Prog. 2024, 40, e3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feidl, F.; Vogg, S.; Wolf, M.; Podobnik, M.; Ruggeri, C.; Ulmer, N.; Wälchli, R.; Souquet, J.; Broly, H.; Butté, A.; et al. Process-Wide Control and Automation of an Integrated Continuous Manufacturing Platform for Antibodies. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 1367–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.M.; Kessler, J.M.; Salou, P.; Menezes, J.C.; Peinado, A. Monitoring MAb Cultivations with In-Situ Raman Spectroscopy: The Influence of Spectral Selectivity on Calibration Models and Industrial Use as Reliable PAT Tool. Biotechnol. Prog. 2018, 34, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, T.A.; Hadley, B.C.; Hilliard, W.; Jaques, C.; Mason, C. Development of Generic Raman Models for a GS-KOTM CHO Platform Process. Biotechnol. Prog. 2018, 34, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandenius, C.F. Measurement Technologies for Upstream and Downstream Bioprocessing. Processes 2021, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.S.; Nikita, S.; Thakur, G.; Deore, N. Challenges in Process Control for Continuous Processing for Production of Monoclonal Antibody Products. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2021, 31, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godawat, R.; Konstantinov, K.; Rohani, M.; Warikoo, V. End-to-End Integrated Fully Continuous Production of Recombinant Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 213, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karst, D.J.; Steinebach, F.; Soos, M.; Morbidelli, M. Process Performance and Product Quality in an Integrated Continuous Antibody Production Process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornecki, M.; Schmidt, A.; Lohmann, L.; Huter, M.; Mestmäcker, F.; Klepzig, L.; Mouellef, M.; Zobel-Roos, S.; Strube, J. Accelerating Biomanufacturing by Modeling of Continuous Bioprocessing—Piloting Case Study of Monoclonal Antibody Manufacturing. Processes 2019, 7, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinebach, F.; Ulmer, N.; Wolf, M.; Decker, L.; Schneider, V.; Wälchli, R.; Karst, D.; Souquet, J.; Morbidelli, M. Design and Operation of a Continuous Integrated Monoclonal Antibody Production Process. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coolbaugh, M.J.; Varner, C.T.; Vetter, T.A.; Davenport, E.K.; Bouchard, B.; Fiadeiro, M.; Tugcu, N.; Walther, J.; Patil, R.; Brower, K. Pilot-Scale Demonstration of an End-to-End Integrated and Continuous Biomanufacturing Process. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 3287–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomis-Fons, J.; Schwarz, H.; Zhang, L.; Andersson, N.; Nilsson, B.; Castan, A.; Solbrand, A.; Stevenson, J.; Chotteau, V. Model-Based Design and Control of a Small-Scale Integrated Continuous End-to-End MAb Platform. Biotechnol. Prog. 2020, 36, e2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sencar, J.; Hammerschmidt, N.; Jungbauer, A. Modeling the Residence Time Distribution of Integrated Continuous Bioprocesses. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15, e2000008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, G.; Saxena, N.; Tiwari, A.; Rathore, A.S. Control of Surge Tanks for Continuous Manufacturing of Monoclonal Antibodies. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1913–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, K.; Kubota, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Iwama, C.; Watanabe, K.; Ishikawa, N.; Tanabe, Y.; Kono, S.; Tanemura, H.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Establishment of a Novel Cell Line, CHO-MK, Derived from Chinese Hamster Ovary Tissues for Biologics Manufacturing. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2024, 137, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfgren, A.; Gomis-Fons, J.; Andersson, N.; Nilsson, B.; Berghard, L.; Lagerquist Hägglund, C. An Integrated Continuous Downstream Process with Real-Time Control: A Case Study with Periodic Countercurrent Chromatography and Continuous Virus Inactivation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 118, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuti-cals for Human Use. Good Manufacturing Practice Guide for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients; International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, A.S.; Thakur, G.; Saxena, N.; Tiwari, A. Surge Tank Based System for Controlling Surge Tanks Automation Control Continuous Manufacturing Train. U.S. Patent Application US17/395,510, 31 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nasukawa-Morimoto, M.; Yamano-Adachi, N.; Omasa, T. From Failures to Insights: The Role of Surge Tanks in Integrated and Continuous Bioprocessing for Antibody Production. Processes 2025, 13, 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103336

Nasukawa-Morimoto M, Yamano-Adachi N, Omasa T. From Failures to Insights: The Role of Surge Tanks in Integrated and Continuous Bioprocessing for Antibody Production. Processes. 2025; 13(10):3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103336

Chicago/Turabian StyleNasukawa-Morimoto, Masumi, Noriko Yamano-Adachi, and Takeshi Omasa. 2025. "From Failures to Insights: The Role of Surge Tanks in Integrated and Continuous Bioprocessing for Antibody Production" Processes 13, no. 10: 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103336

APA StyleNasukawa-Morimoto, M., Yamano-Adachi, N., & Omasa, T. (2025). From Failures to Insights: The Role of Surge Tanks in Integrated and Continuous Bioprocessing for Antibody Production. Processes, 13(10), 3336. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13103336