Serious Games, Mental Images, and Participatory Mapping: Reflections on a Set of Enabling Tools for Capacity Building

Abstract

1. Introduction

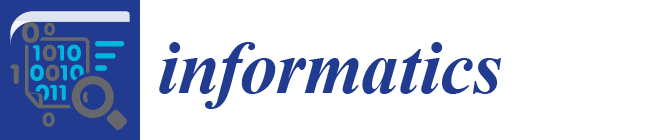

2. The Promise of the Capability Approach Framework

3. The Context

4. Mapping the Invisible: A Capacity Building Process

- Tools for surveying and mapping the existing situation (e.g., social media monitoring, face-to-face surveys).

- Tools for providing information about the progress of the project under the form of one way communication (e.g., via social media, the local press, policy documents and reports).

- Tools for collecting knowledge and gathering feedback through discussion about existing plans for the refurbishment of the street (e.g., neighborhood manager meetings with focus groups, workshops).

- Productive tools—tools that allow for proposing alternative solutions (co-design workshops).

- Decision-making tools allowing proprietors to vote on project proposals.

4.1. Participatory Mapping

4.1.1. Setting

4.1.2. Benefits

4.2. Mental Images

4.2.1. Setting

4.2.2. Benefits

4.3. Serious Games

4.3.1. Floating City

4.3.2. City Makers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Online Questionnaire

- Through your professional occupation, in how many participatory projects were you involved in the last five years?

- In which field do the projects you are involved with, include participatory processes?

- Which social groups are over-, underrepresented, or completely missing from the participatory process?

- Which gender groups are over-, underrepresented or completely missing from the participatory process?

- Which age groups are over-, underrepresented, or completely missing from the participatory process?

- How are participation processes initiated?

- How much influence do the participants have on setting the rules of the participatory processes

- What’s the average duration of participation projects?

- What’s the type of events employed in participation projects?

- What kind of tools are employed the most in these participatory processes?

Appendix B. Semi-Structured Interview

- 0. Can you briefly explain the aim and goals of your organization and your position?

- 0. What kind of experience do you have with participatory processes?

- 0. How do you personally participate? What is your role in the participatory process?

- What are the goals of actor involvement in the framework of this particular project?

- Can you describe the participation processes in the projects?

- Which tool(s) did you find as being most productive in terms of the process and quality of outcome? Why/How?

- What is your motivation for using participatory processes?

- What are your expectations?

- What are the incentives for e.g., private persons, who take part in these processes over a period of time?

- How do you reach out to potential participants?

- When does the process stop? How do you know, when it’s finished?

- When do people drop out, and who is dropping out of the process?

- Why in your opinion people stop participating?

- Who decides on rules? Can they be changed?

- Are participants generally accepting and playing by rules?

- Do participants bend, ignore or break the rules?

- Which kind of conflicts surface during a participation process?

- How do you deal with power differentials within the group?

- How do you deal with knowledge and time availability differentials within the group?

- How do you deal with people who obstruct the process? (e.g., By bullying other participants, hampering or screaming?)

- How satisfied are you with the outcomes? Did they match your expectations?

- How much influence do existing participatory processes have on actual planning policies or plans?

- How do you manage expectations on the part of participants?

References

- Schouten, B.; Ferri, G.; de Lange, M.; Millenaar, K. Games as Strong Concepts for City-Making. In Playable Cities, Gaming Media and Social Effects; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, L.; Blomberg, J.; Orr, J.E.; Trigg, R. Reconstructing Technologies as Social Practice. Am. Behav. Sci. 1999, 43, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horelli, L. A Methodology of Participatory Planning. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 607–628. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, A.A. Participatory Methods and the Capability Approach. Human Development and Capability Association Briefings. Available online: http://www.capabilityapproach.com/pubs/Briefing_on_PM_and_CA2.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2006).

- Ranciere, J. Staging the People: The Proletarian and His Double; Verso: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-84467-697-2. [Google Scholar]

- Frediani, A.A. The Capability Approach as a Framework to the Practice of Development. Dev. Pract. 2010, 20, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterlaken, I. Design for Development: A Capability Approach. Des. Issues 2009, 25, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Capability Expansion. In Readings in Human Development; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach and Its Implementation. Hypatia 2009, 3, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Country of First Boys: And Other Essays; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9780198738183. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Human Rights and Capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S. Valuing Freedoms: Sen’s Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, C. Irreducible social goods and the informational basis of Amartya Sen’s capability approach. J. Int. Dev. 1997, 9, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach: A theoretical survey. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S. Choosing dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/127875/WP88_Alkire.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Madanipour, A. Whose Public Space? International Case Studies in Urban Design and Development; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence; HarperCollins Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, E.J.; Booher, D.E. Planning with Complexity—An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, A. The Policy of Design: A Capabilities Approach. Des. Issues 2008, 24, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehn, P. Participation in Design Things. In Proceedings of the Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, E. Formatted Spaces of Participation: Interactive television and the changing relationship between production and consumption. In Digital Material—Tracing New Media in Everyday Life and Technology; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2009; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O. Portraits of Work: Mapping Emerging Coworking Dynamics; Information, Communication & Society: Manchester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Belgian Statistical Office—Stadbel. Available online: https://statbel.fgov.be/en (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Constantinescu, T.; Devisch, O.; Kostov, G. City Makers: Insights on the Development of a Serious Game to Support Collective Reflection and Knowledge Transfer in Participatory Processes. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, A. Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 547–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, J.; Loxley, A. Introducing Visual Methods. Available online: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/420/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-010.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Roseneil, S. The ambivalences of angel’s “arrangement”. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 54, 847–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. Making: Anthropology. Archaeology: Art and Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Wurman, R.S. Information Anxiety: Towards Understanding. Available online: https://scenariojournal.com/article/richard-wurman/ (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Tufte, E. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire Connecticut. Available online: http://www.colorado.edu/UCB/AcademicAffairs/ArtsSciences/geography/foote/maps/assign/reading/TufteCoversheet.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Amoroso, N. The Exposed City: Mapping the Urban Invisible; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sulsters, W. Mental Mapping: Viewing the Urban. Landscapes of the Mind. Available online: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:fc71de16-b485-4888-b6fe-a9d2771d9e4a (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Rogers, Y.; Marsden, G. Does he take sugar? Moving beyond the rhetoric of compassion. Interactions 2013, 20, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vines, J.; Clarke, R.; Wright, P.; McCarthy, J.; Olivier, P. Configuring Participation: On How We Involve People in Design. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, M.J. The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook. Chapter Participatory Design: The Third Space in HCI; L. Erlbaum Associates Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 1051–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Abt, C. Serious Games; Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, R. Metropolis: The Urban Systems Game; Gamed Simulations, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, M. Critical Play: Radical Game Design; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- De Lange, M. ECLECTIS Report: A Contribution from Cultural and Creative Actors to Citizens’ Empowerment. Available online: https://waag.org/sites/waag/files/media/publicaties/publication_eclectis_bd.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Tan, E.; Portugali, J. The Responsive City Design Game. In Complexity Theories of Cities Have Come of Age; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 369–390. [Google Scholar]

- Rieser, M. Locative voices and cities in crisis. Studies in documentary film. In Playable Cities: The City as a Digital Playground; Springer: Singapore, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, E.; Baldwin-Philippi, J. Playful Civic Learning: Enabling Reflection and Lateral Trust in Game-based Public Participation. Int. J. Commun. 2014, 8, 759–786. [Google Scholar]

- Ashiem, B.; Cohen, L.; Vang, J. Face-to-face, buzz and knowledge bases: Socio-spatial implications for learning, innovation and innovation policy. Environ. Plann. C 2007, 25, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Cultural Action for Freedom; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ranciere, J.; Corcoran, S. Dissensus on Politics and Aesthetics; Continuum London: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern. Crit. Enq. 2004, 30, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Capability Approach Conversion Factors | Existing Functionings/Enabling Tools | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choice provision of alternative participatory mechanisms essential to improve democracy among citizens and enable them to participate actively | Content of the Process | How is public administration represented in the process? | Municipal Level is involved and well represented or overrepresented in the process Regional Scale is represented Supra-regional level is underrepresented to missing | |

| How is public administration involved in particular? | Public Servants as facilitators (experienced in facilitating methods and brainstorming techniques) | |||

| Does administration fund/sponsor the process? | Public funding for neighbourhood management and process | |||

| Who is launching the content/subjects of different processes? | Municipality, Consortium of organizational /institutional partners, activist groups/initiatives Individual Actors, Local Associations/Private Market Parties | |||

| Participatory Methods | Methods | Which methods are applied and facilitated? | Focus on traditional methods: focus groups, workshops/brainstorming techniques, meetings/discussion rounds, extended by Social Media Platforms | |

| Level of participation | Level of participation in general and in particular project | Focal Points: Information - Consultation - Placation - Partnership | ||

| Capacity | Are the participants able to express their interests? | Yes | ||

| Does the process include making proposals? | Yes | |||

| Process design | Who decides on the usage of methods/tools? | Neighbourhood Management (leadership) | ||

| Ability (1) how individuals engage in the deliberation process and (2) their relationship with different actors involved in this process | Coordination | Agreement | How far is the processes politically accepted? | High: Urban Scale: political commitment |

| How intensively is the political domain involved in the process? | Intensively: a process that grew in the past 20 years due to the recognition from the political domain of its importance | |||

| Are the involved/responsible political actors committed to the results? | Yes | |||

| Leadership & Integration | Who is leading the process? | City administration Neighbourhood scale | ||

| Is the process linked to other initiatives? | Yes Wijk Management is linked to other neighbourhoods and different departments, Wijk Management (as intermediary position between municipality - neigbourhood - citizens) | |||

| Resources | Has the process necessary resources (money, room, etc.)? | No | ||

| Are there resource restrictions on participant level? | Time, Knowledge, Language Barriers, Cultural Restrictions | |||

| Design | Are the processes designed? Was there a deliberate design process? | Partly | ||

| Participants | Methods | How are the participants chosen? (democratically) | Open for everybody to join: Invitation Letter to all inhabitants Social Media, newspapers, direct approach/invitation by Wijk Managers | |

| Extent | Is there stability of the number of participants over time? | Enthusiasm in the beginning - fluctuating throughout the process, people dropping out | ||

| Diversity | Age Groups | Adults & working population age group: well represented 25-64 years Representation of young adults in a transition zone Teens and children: underrepresented Elderly people (65+): tendency for overrepresentation | ||

| Is there gender equality in the process? | Male: well represented - overrepresented Female: represented - underrepresented | |||

| Communication | How is communication organised? (within the process) | Initiative: social media, professional networking, personal meetings Leadership: meetings | ||

| Opportunity to engage in the deliberation phase of the capacity building process in order to assess the effectiveness of participation | Implementation/Impact | Influence | Are there plans/designs/actions produced? | Yes |

| Were the results implemented in policy, action, program so far? | Urban Scale, used as policy guideline | |||

| To whom are they addressed? | Alderman and Public Administration | |||

| Are there documents with the results of the process? Could the participants influence those documents? | Participants ideas were incorporated in the ‘Genk in Sight: Future Scenarios of Genkenaars on their City’ report. Will take initiatives to stimulate and integrate the ideas in the policy and bring them to live | |||

| Learning | Are there training sessions foreseen? | Yes | ||

| Implementation | Have the results been implemented? | Partly (smaller actions) the main part is in the initial phase | ||

| Capability Approach Conversion Factors | Capacity Building Process | Enabling Tools/Artefacts |

|---|---|---|

| Choice provision of alternative participatory mechanisms essential to improve democracy among citizens and enable them to participate actively | The provision of alternative artefacts is crucial to enhance proprietors’ freedom in participating in planning processes. What type of tools can proprietors use to engage in the planning process of the shopping street? | serious games—structured tools, complemented by participatory mapping and mental images as unstructured tool that support people in the endeavor of understanding their conversion factors |

| Ability (1) how individuals engage in the deliberation process and (2) their relationship with different actors involved in this process | (how) Are entrepreneurs engaged in the process of deliberation? What is their relations with outside actors (i.e., architects, engineers, policy makers etc.)? What are entrepreneurs’ diverse capacities to appropriate the space of the street a/o urban interventions? (how) Can the capabilities and ties of each proprietor be identified, enhanced and later used to feed a participatory process? Can we talk about collective capacities (i.e., generate collective action, collectively appropriate, change, maintain or improve the built space of Vennestraat)? (How) can we capture appropriate social narratives as data providers in developing a capacity-building process? | participatory mapping to draw entrepreneurs’ networks and their dynamics mental images to capture social narratives and entrepreneurs’ perception of their surroundings serious games as environments that present a simplified version of the spatial transformation processes taking place in ones’ surrounding |

| Opportunity to engage in the deliberation phase of the capacity building process, under the role of partners, informants, or actors of change in order to assess the effectiveness of participation | Social, economic, and political processes shaping proprietors’ freedom to take part in the process of deliberation and appropriate outcomes of the capacity building process. How far does participation go? Does it build on networks among different (groups of) proprietors and expand room for maneuvering to influence or change policy-making? | participatory mapping to analyze the potential of proprietors’ connections to shape the urban space mental images seize proprietors’ ‘personal conversion factors’ serious games as catalysts in building /strengthening communities and creating interactions |

| Name | Floating City |

|---|---|

| Target Group/Age | 9+ |

| How many players can play? | 1+ |

| Playing Time | 5–10 min with 15 min for debriefing |

| Short Description (Goal, narrative) | A brainstorming game for public spaces in which players can create and publicize their ideas and suggestions for city projects. A balloon is generated for every new idea and slowly elevates the city. Existing balloons can be viewed and rated by others to increase or decrease their effects on the city. All of the generated ideas and their ratings are automatically saved and are available for evaluation after all game sessions. |

| What do players learn/experience? | Players are proposing ideas, needs, wishes, values, and visions to adapt or improve their city. Each input is represented in a balloon that is carrying the city. Other players can weigh (thumbs up/down) those ideas and add comments. Voting for ideas and clustering them increases insight in the diversity of values among players regarding sustainable futures. A feeling of shared values. |

| Game rules | The game master or moderator poses a question for the audience. Players then have the possibility to generate their own answers and contributions and to like or comment on the ideas from other players. One round takes as long as the city needs to reach the top of the atmosphere. Then, either a new round starts or another question can be posed. All ideas are represented as balloons that are helping the city fly higher and higher. The more votes a balloon gets, the higher it pulls the city. High balloons then represent shared values. The number of balloons is an indication for the diversity of values. |

| Equipment/Game material/Interface | The equipment consists of a laptop, monitor/projector, and one keyboard. |

| Setting (open/closed, suitable for festivals.....) | The game works best in a workshop setting or festival (in this case, it should be used as an idea collector). Playing the game simultaneously with multiple groups may increase the value of the debriefing. |

| Additional requirements that are necessary to play the game (i.e., tables, quiet environment, necessary space) | There are no additional requirements. |

| Persons necessary for facilitation (game master) | The game requires a game master to allow for a constructive debriefing. |

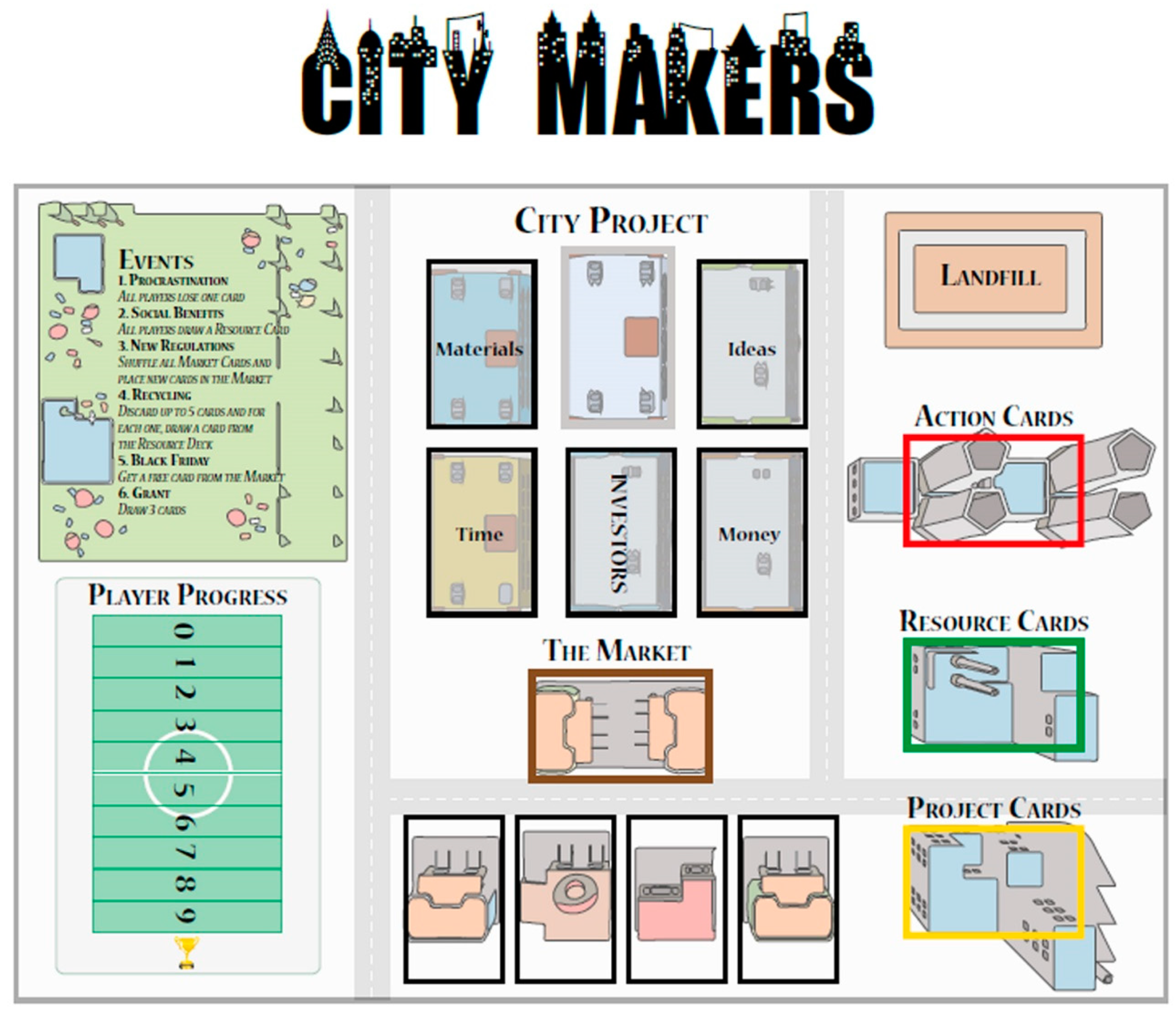

| Name | City Makers |

|---|---|

| Target Group/Age | 12+ |

| How many players can play? | 3–6 |

| Playing Time | 30–40 min with 15 min for debriefing |

| Short Description (Goal, narrative) | Players have to develop projects to improve the livability of a given neighborhood or city. In order to complete these projects, they can either chose to compete or to collaborate. The players can earn credits by completing projects, investing in each other’s projects, or investing in community projects. The player who reaches ten points first wins the game. |

| What do players learn/experience? | The players are asked to present (given) projects as a set of steps that they need to collect resources (material, permit and location) for. By doing so, players will learn about the procedures that are required to implement these projects. This may, in turn, trigger them to actually consider implementing a project. |

| Game rules | Each player receives a project (in the form of a card) that he/she needs to finish to acquire points. For example, to start a business one might need to have a budget, idea, location, and people to work with. The player, who reaches ten points first wins. The game consists of four sets of cards: project, resource, market, and action cards. They are placed in the predefined deck positions. One project and four market cards are drawn from the decks and placed so everyone can see them. Everyone receives three color tokens—one for representing them on the field and two for investments—, three player cards, and a project. Players are then allowed to draw an additional resource card each turn, trade with everyone, and do only one of the following: finish one step of their project, invest in the common project or another player’s project, or play an action card. |

| Equipment/Game material/Interface | The equipment consists of a (printable) game-board and a (printable) set of cards. |

| Setting (open/closed, suitable for festivals...) | The game works best in a workshop setting. Playing the game simultaneously with multiple groups may increase the value of the debriefing. |

| Additional requirements that are necessary to play the game (i.e., tables, quiet environment, necessary space) | There are no additional requirements. |

| Persons necessary for facilitation (game master) | The game requires a game master and an observant. The observant documents the gameplay to allow for a constructive debriefing. |

| Capability Approach Conversion Factors | Capacity Building Process | Enabling Tools/Artefacts |

|---|---|---|

| Choice provision of alternative participatory mechanisms essential to improve democracy among citizens and enable them to participate actively | ● Analyzing a/o addressing social needs ● Experimentation with disruptive tools ● Deliberate use of ideas a/o mechanism that seek to challenge the existing practices established in the street ● Measures or resources to allow direct involvement of proprietors in participatory processes or independently realize their freedoms to act ● Involvement of diverse (groups of) actors in the process | serious games—structured tools, complemented by participatory mapping and mental images as unstructured tool that support people in the endeavor of understanding their conversion factors |

| Ability (1) how individuals engage in the deliberation process and (2) their relationship with different actors involved in this process | ● A variety of actors involved throughout the process ● Integrating into the design of the street different opinions voiced by proprietors ● Involvement of various and multiple stakeholders in knowledge production processes ● Stakeholders reflecting on capacity building processes ● Capacity building in relation to building social capital by creating relations of trust between proprietors or formal communication channels for marginalized shop owners that could facilitate future collaboration ● Recognizing systemic barriers (e.g., regulations, physical barriers, cultural values) that need to be overcome for various interventions on the street to become viable or successful and ● Formulate explicit strategies to overcome such path dependencies | participatory mapping to draw entrepreneurs’ networks and their dynamics mental images to capture social narratives and entrepreneurs’ perception of their surroundings serious games as environments that present a simplified version of the spatial transformation processes taking place in ones’ surrounding |

| Opportunity to engage in the deliberation phase of the capacity building process, under the role of partners, informants, or actors of change in order to assess the effectiveness of participation | ● Leadership acting as a driving collaborative force in the process ● Agendas aiming to tackle sustainability challenges ● Shape an explicit future shared vision of the street ● Project activities contributing to capacity development across human action levels ● Strategies seeking to reveal proprietors freedoms and quality of life ● Providing entrepreneurs with new skills, training, abilities and improved access to participatory processes tackling the future development of the street ● Formulate ideas that are (1) explicit, (2) aim for radical change, and (3) supported by a wide range of proprietors | participatory mapping to analyze the potential of proprietors connections to shape the urban space mental images seize proprietors’ ‘personal conversion factors’ serious games as catalysts in building/strengthening communities and creating interactions |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Constantinescu, T.I.; Devisch, O. Serious Games, Mental Images, and Participatory Mapping: Reflections on a Set of Enabling Tools for Capacity Building. Informatics 2020, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7010007

Constantinescu TI, Devisch O. Serious Games, Mental Images, and Participatory Mapping: Reflections on a Set of Enabling Tools for Capacity Building. Informatics. 2020; 7(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleConstantinescu, Teodora Iulia, and Oswald Devisch. 2020. "Serious Games, Mental Images, and Participatory Mapping: Reflections on a Set of Enabling Tools for Capacity Building" Informatics 7, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7010007

APA StyleConstantinescu, T. I., & Devisch, O. (2020). Serious Games, Mental Images, and Participatory Mapping: Reflections on a Set of Enabling Tools for Capacity Building. Informatics, 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7010007