Art in the Age of Social Media: Interaction Behavior Analysis of Instagram Art Accounts

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Questions

- RQ1: What kind of artwork gets the most likes and comments?

- RQ2: What makes people press the “like” button and comment on the artwork?

- RQ3: What is the relationship between interactions, likes and comments?

- RQ4: Are female artists more popular?

- RQ5: Do the most-liked artwork also the best artworks considered by the artist?

- RQ6: Do the most-liked artwork influence the artist’s creation?

1.2. Definitions of Key Terms

1.2.1. Artwork

1.2.2. Self-Actualization

2. Theoretical Background

3. Methodology

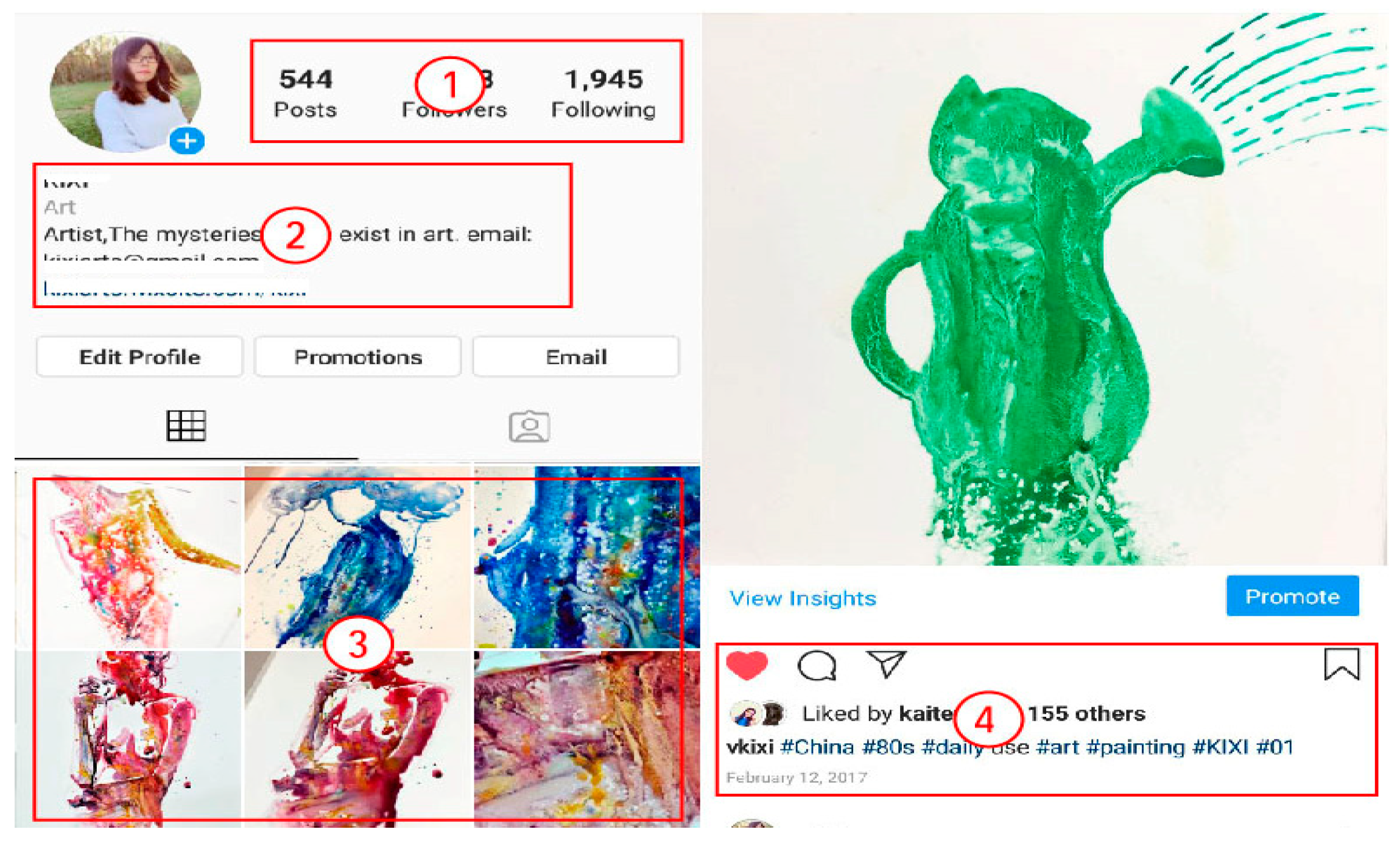

3.1. Study 1

- #painting (#oilpainting, #watercolorpainting, #watercolors, and #acrylicpainting, etc.)

- #Illustration (#cartoonist, #cartooning, #cartoonart, #comicstyle, and #indiecomic, etc.)

- #digitalpainting (#digitalart, #digitalart, #characterdesign, #digitaldrawing, #animation, and #gameart, etc.)

3.2. Study 2

4. Data Analysis and Results

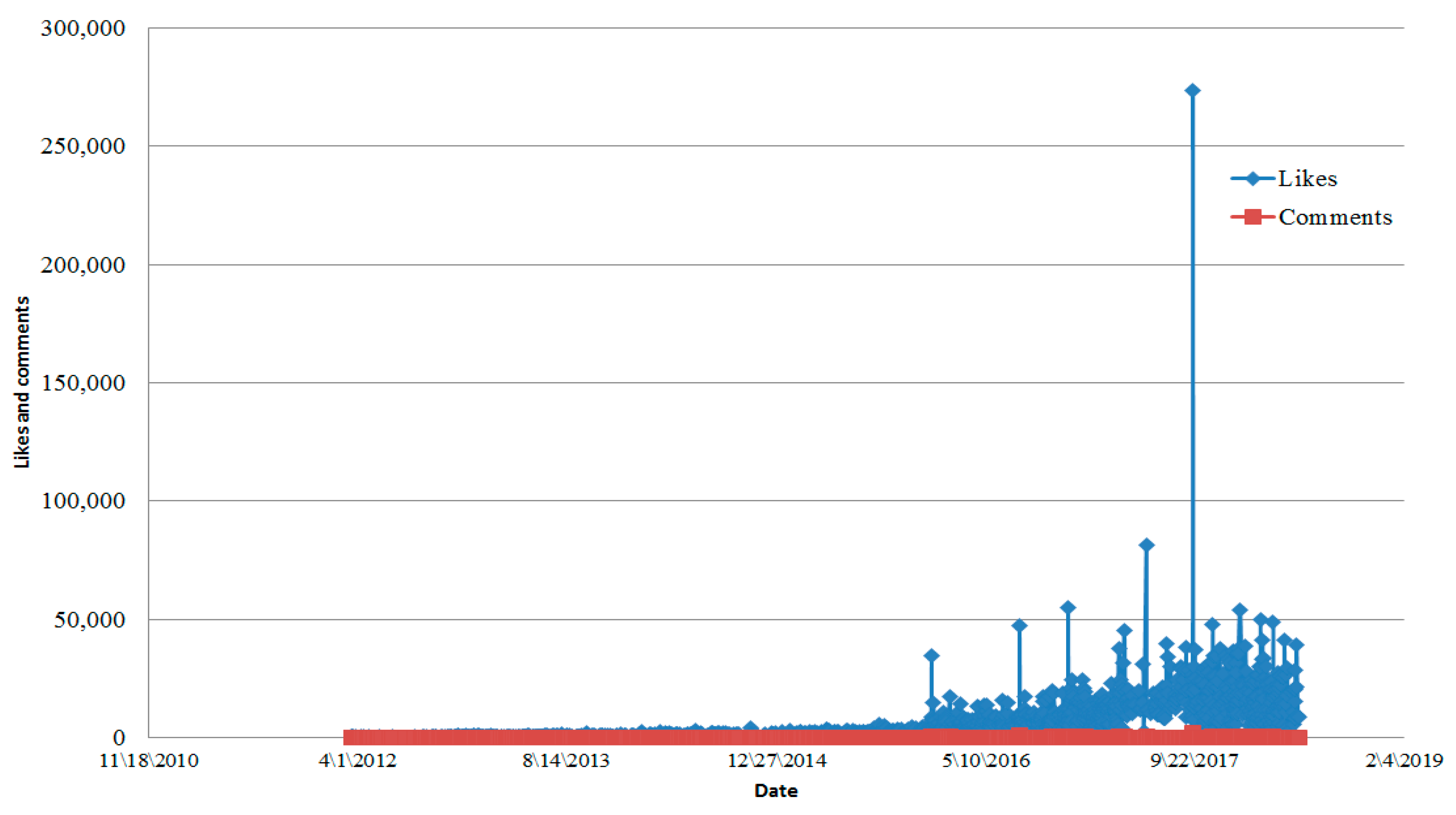

4.1. Findings of Study 1

4.1.1. The Most-Liked Artworks

4.1.2. The Most-Commented Artworks

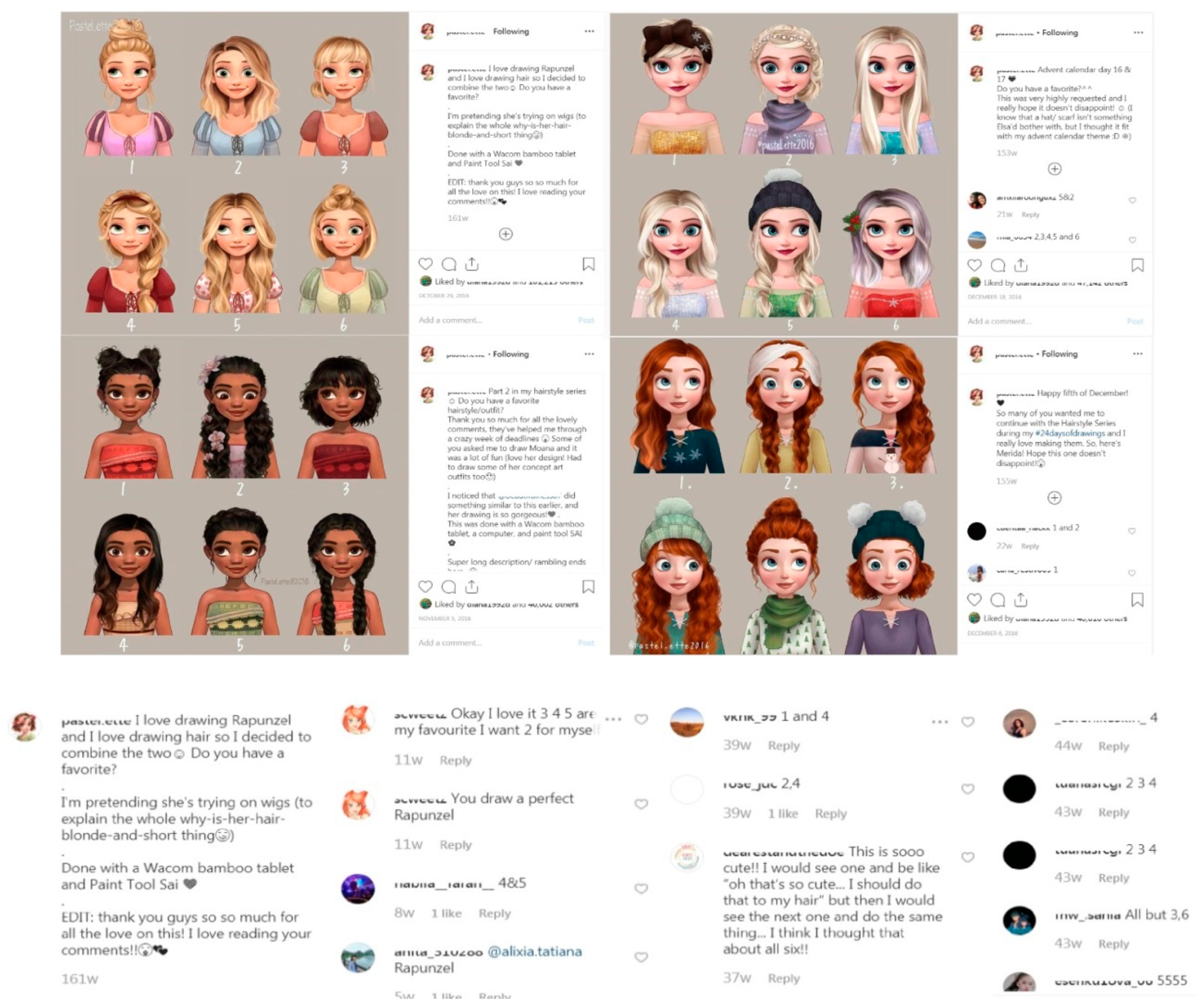

4.2. Discussion 1

- Practical information sharing (sharing tutorials or painting process);

- Ask a question: “what do you think?”;

- Arouse curiosity: “what is this?”;

- Interesting or humorous illustration;

- Empathy.

4.2.1. Practical Information

4.2.2. Asking Questions

4.2.3. Curiosity

4.2.4. Interestingness

4.2.5. Empathy

4.3. Findings of Study 2

- The most preferred social media platform is Instagram (91%), and the most used social media for art-related purposes is Instagram (94%) too;

- The main motivations of using social media are to share artworks, selling artworks and know more artists;

- 37% of artists post 5 to 10 posts a week, 46% of artists are interacting with followers more than 10 times per week;

- 80% of artists deny that the most-liked artwork is also their favorite artwork;

- 63% of artists deny that the interaction between the most-liked artwork and followers will influence the creation of their next artwork;

- 63% of artists did not customize the artwork for their followers.

4.4. Discussion 2

5. General Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McAndrew, C. The Art Market 2018 An Art Basel & UBS Report; UBS: Zurich, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, J. Art in the Age of Instagram. Available online: https://www.speeches.io/art-in-the-age-of-instagram-jia-jia-fei-tedxmarthasvineyard-with-evaluation-form/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Hiscox. Hiscox Online Art Trade Report; Hiscox: Hamilton, Bermuda, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Capriotti, P. Museums’ communication in small-and medium-sized cities. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2010, 15, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenn, G.; Vidal, G. Les Musées Français et Leurs Publics a L’âge du Web 2.0. Nouveaux Usages du Multimédia et Transformations des Rapports Entre Institutions et Usagers; Archives & Museum Informatics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaëlle, C. Les musées français et leurs publics à l’âge du web 2.0. Nouveaux usages du multimédia et transformations des rapports entre institutions et usagers? In Proceedings of the International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meetings, Toronto, ON, Canada, 24–26 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. A learning assessment of online interpretation practices: From Museum supply chains to experience ecologies. Inf. Commun. Technol. Tour. 2005, 2005, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, M.L. Critical analysis of blogging in public relations. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowsky, J. Art in the Instagram Age: How Social Media Is Shaping Art and How You Experience It. 2017. Available online: https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/visual-arts/art-in-the-instagram-age-how-social-media-is-shaping-art-and-how-you-experience-it/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Hakanen, E.A. Branding the Teleself: Media Effects Discourse and the Changing Self; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, B. From arts marketing to audience enrichment: How digital engagement can deepen and democratize artistic exchange with audiences. Poetics 2016, 58, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D. Managing change in museums. In Proceedings of the Museum and Change International Conference, National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic, 8–10 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, O. Why the World’s Most Talked-About New Art Dealer Is Instagram. Available online: https://www.vogue.com/article/buying-and-selling-art-on-instagram (accessed on 13 May 2014).

- Manovich, L. Instagram and Contemporary Image; Manovich. NET: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, N. Digital: Museum as platform, curator as champion, in the age of social media. Curator Mus. J. 2010, 53, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, H. Walker Visitors Vote for Half the Works to View in New Show. 2010. Available online: http://www.artnews.com/2010/12/01/citizen-curators/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- McLuhan, M. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man; Marshall McLuhan; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Deighton, J.; Sorrell, M. The future of interactive marketing. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Valcanis, T. An iPhone in every hand: Media ecology, communication structures, and the global village. Etc A Rev. Gen. Semant. 2011, 68, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manovich, L. Cultural Analytics: Visualising Cultural Patterns in the Era of “More Media”; Domus: March, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Cheng, H.K.; Duan, Y.; Jin, Y. The power of the “like” button: The impact of social media on box office. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 94, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, J.; Lankinen, M.; Mäntymäki, M. The use of social media for artist marketing: Music industry perspectives and consumer motivations. Int. J. Media Manag. 2013, 15, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshi, S.; Shamma, D.A.; Kennedy, L.; Gilbert, E. Why we filter our photos and how it impacts engagement. In Proceedings of the Ninth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Oxford, UK, 26–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Simo-Serra, E.; Fidler, S.; Moreno-Noguer, F.; Urtasun, R. Neuroaesthetics in fashion: Modeling the perception of fashionability. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Segalin, C.; Cheng, D.S.; Cristani, M. Social profiling through image understanding: Personality inference using convolutional neural networks. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2017, 156, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherren, K.; Parkins, J.R.; Smit, M.; Holmlund, M.; Chen, Y. Digital archives, big data and image-based culturomics for social impact assessment: Opportunities and challenges. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2017, 67, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaak, S. What Are the Visual Arts? 2019. Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/what-are-the-visual-arts-182706 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Wikipedia. New Media Art. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_media_art#cite_ref-3 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Modell, A.H. The Private Self; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, D. The intersection of art and interactivity. Ars Electron. Festiv. 1996, 96, 274–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, J.; Bradburne, J.; Burch, A.; Dierking, L.; Falk, J. Digital Technologies and the Museum Experience: Handheld Guides and Other Media; Rowman Altamira: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kristin, T.; Kristen, P.; Lee, R. Arts Organizations and Digital Technologies. 2013. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/04/arts-organizations-and-digital-technologies/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, J.A.; Moon, J.H.; Sung, Y. Pictures speak louder than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self: Goffman Drmaturgical Model; Indiana Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life; Harmondsworth: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.J. Community Building on the Web: Secret Strategies for Successful Online Communities Community; Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.-Q.; Chen, H.-G. Social media and human need satisfaction: Implications for social media marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2015, 58, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Kim, Y.; Kasser, T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, N.K. Connect with your audience! The relational labor of connection. Commun. Rev. 2015, 18, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kenneth, O.; Cliff, L.; Nicole, B.E. Social Media and the Workplace. 2017. Available online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/06/22/social-media-and-the-workplace/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Nabi, I.R. Instagram: Motives for its Use and Relationship to Narcissism and Contextual Age; Bahria University Karachi Campus: Karachi, Pakistan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hochman, N.; Schwartz, R. Visualizing instagram: Tracing cultural visual rhythms. In Proceedings of the Sixth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Dublin, Ireland, 4–7 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- You, Q.; García-García, D.; Paluri, M.; Luo, J.; Joo, J. Cultural diffusion and trends in facebook photographs. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Montréal, QC, Canada, 15–18 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.J.; Wang, H. Examining hedonic and utilitarian motivations for m-commerce fashion retail app engagement. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 20, 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzen, K.; Bala, K.; Snavely, N. Streetstyle: Exploring world-wide clothing styles from millions of photos. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706,01869. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Manikonda, L.; Kambhampati, S. What we instagram: A first analysis of instagram photo content and user types. In Proceedings of the Eighth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Sjöklint, M.; Ukkonen, A. The sharing economy: Why people participate in collaborative consumption. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Chen, W. The Like Economy: The Impact of Interaction between Artists and Fans on Social Media in Art Market. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business and Information Management, Beijing, China, 23–25 July 2017; ACM: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wikiart. ARTWORKS BY GENRE. Available online: https://www.wikiart.org/en/paintings-by-genre (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Bourdieu, P.; Darbel, A. The Love of Art; European Art Museums and their Public, Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McCornack, S.; Ortiz, J. Choices & Connections: An Introduction to Communication; Macmillan Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi, S.; Shamma, D.A.; Gilbert, E. Faces engage us: Photos with faces attract more likes and comments on instagram. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 1–26 April 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Redies, C. Combining universal beauty and cultural context in a unifying model of visual aesthetic experience. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, A.; Nagao, K. Communicative facial displays as a new conversational modality. In Proceedings of the INTERACT’93 and CHI’93 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 24–29 April 1993; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A.I.; Sripada, C.S. Simulationist models of face-based emotion recognition. Cognition 2005, 94, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam Webster. Intuition. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/intuition (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Wilson, T.D.; Schooler, J.W.; Schooler, J.W. Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. What to Post on Instagram: 15 Creative and Engaging Ideas. 2019. Available online: https://blog.hootsuite.com/instagram-post-ideas/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Jenkins, H. Interactive Audiences; The New Media Book: London, UK, 2002; pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zuss, M. The Practice of Theoretical Curiosity; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A.; Mehrabian, A. Distinguishing anger and anxiety in terms of emotional response factors. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, C.; Piantadosi, S.T.; Aslin, R.N. The Goldilocks effect: Human infants allocate attention to visual sequences that are neither too simple nor too complex. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupchik, G.C.; Gebotys, R.J. Interest and pleasure as dimensions of aesthetic response. Empir. Stud. Arts 1990, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.S. Emotion, art, and the humanities. Handb. Emot. 2000, 3, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hagtvedt, H.; Patrick, V.M.; Hagtvedt, R. The perception and evaluation of visual art. Empir. Stud. Arts 2008, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Hanania, R.; Davidov, M.; Zahn-Waxler, C. Empathy development from 8 to 16 months: Early signs of concern for others. Infant Behav. Dev. 2011, 34, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P. 8 Reasons Why Social Media is Decimating Art and Literature. 2014. Available online: https://qwiklit.com/2014/03/08/8-reasons-why-social-media-is-decimating-art-and-literature/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Sharlow, S. Death of An Artist: How Social Media Is Ruining Creativity. 2015. Available online: https://www.elitedaily.com/life/culture/death-artist-social-media-ruining-creativity/907113 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Whitehead, K. Is Social Media Killing Art or Bringing it to the People? Available online: https://www.scmp.com/culture/arts-entertainment/article/2074306/social-media-killing-art-or-bringing-it-people (accessed on 28 Feburary 2017).

- Maharani, N.; Sevriana, L. Analysis of Attitude, Motivation, Knowledge and Lifestyle of the Consumers in Bandung Who Shop through Instagram. Winners 2017, 18, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Polaine, A. Lowbrow, high art: Why Big Fine Art doesn’t Understand Interactivity. Available online: http://pl02.donau-uni.ac.at/xmlui/handle/10002/563. (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Shoemaker, P.J.; Vos, T. Gatekeeping Theory; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. Forces behind food habits and methods of change. Bull. Natl. Res. Counc. 1943, 108, 35–65. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, L. Taking Back the Arts: 21st Century Audiences, Participatory Culture and the End of Passive Spectatorship. L’ordinaire Des Amériques 2016, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltissen, R.; Ostermann, B.-M. Are the dimensions underlying aesthetic and affective judgment the same? Empir. Stud. Arts 1998, 16, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P.J. Emotional responses to art: From collation and arousal to cognition and emotion. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2005, 9, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manovich, L. Notes on Instagrammism and Mechanisms of Contemporary Cultural Identity (and Also Photography, Design, Kinfolk, k-pop, Hashtags, Mise-en-Scène, and Cостояние). 2016. Available online: http://manovich. net/index. php/projects/instagram-and-contemporary-image (accessed on 29 October 2019).

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||||

| Male | 319 | 45.2 | 45.2 | 45.2 | ||||

| Female | 387 | 54.8 | 54.8 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total | 706 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||||

| Followers | 706 | 433 | 2,146,849 | 92,914.61 | 186,406.308 | |||

| Followings | 706 | 1 | 7499 | 876.17 | 1141.704 | |||

| Posts | 706 | 14 | 10,927 | 704.89 | 867.539 | |||

| Likes | 706 | 101 | 362,297 | 11,080.65 | 25,491.960 | |||

| Comments | 706 | 2 | 21,911 | 179.02 | 997.674 | |||

| Valid N (listwise) | 706 | |||||||

| Frequency | Followers | Following | Posts | Likes | Comments | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Painting | 519 | 46,606,438 | 481,383 | 379,395 | 5,200,716 | 88,759 | 73 |

| #Digitalpainting | 35 | 3,181,762 | 19,509 | 19,421 | 472,168 | 4312 | 22 |

| #Illustration | 152 | 15,809,518 | 117,683 | 98,833 | 2,150,053 | 33,314 | 5 |

| Statistics | ||||||||

| Gender | Age | Years of Being an Artist | Education | |||||

| N | Valid | 35 | 35 | 35 | 35 | |||

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||||

| Valid | Male | 15 | 42.9 | 42.9 | 42.9 | |||

| Female | 20 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||||

| Valid | 20–29 | 10 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 28.6 | |||

| 30–39 | 12 | 34.3 | 34.3 | 62.9 | ||||

| 40–49 | 4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 74.3 | ||||

| 50–59 | 8 | 22.9 | 22.9 | 97.1 | ||||

| 60+ | 1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Years of Being an Artist | ||||||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||||

| Valid | <1 year | 1 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | |||

| 2–3 years | 5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 17.1 | ||||

| 3–5 years | 3 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 25.7 | ||||

| 5–10 years | 5 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 40.0 | ||||

| >10 years | 21 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Frequency | Percent | Valid Percent | Cumulative Percent | |||||

| Valid | College graduate | 17 | 48.6 | 48.6 | 48.6 | |||

| Post graduate degree | 9 | 25.7 | 25.7 | 74.3 | ||||

| High school graduate | 4 | 11.4 | 11.4 | 85.7 | ||||

| Some college | 3 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 94.3 | ||||

| Trade/technical/vocational training | 2 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 100.0 | ||||

| Total | 35 | 100.0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Descriptive Statistics | ||||||||

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||||

| Posts | 35 | 59 | 2245 | 756.26 | 558.908 | |||

| Followers | 35 | 5384 | 397,000 | 44,778.77 | 67,136.883 | |||

| Following | 35 | 116 | 6475 | 1078.46 | 1286.042 | |||

| Valid N (listwise) | 35 | |||||||

| ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likes | |||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

| Between Groups | 1.819 × 109 | 1 | 1.819 × 109 | 2.806 | 0.094 |

| Within Groups | 4.563 × 1011 | 704 | 6.482 × 108 | ||

| Total | 4.581 × 1011 | 705 | |||

| Number of Cases in each Cluster | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster | 1 | 654.000 | |||

| 2 | 6.000 | ||||

| 3 | 46.000 | ||||

| Valid | 706.000 | ||||

| Missing | 0.000 | ||||

| Final Cluster Centers | |||||

| Cluster | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Followers | 54,535 | 1,638,814 | 436,939 | ||

| Followings | 901 | 328 | 601 | ||

| Posts | 662 | 1134 | 1265 | ||

| Likes | 6481 | 195,449 | 52,430 | ||

| Comments | 84 | 2166 | 1270 | ||

| Group Statistics | |||||||

| Gender | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | |||

| Customize | Male | 15 | 1.93 | 0.258 | 0.067 | ||

| Female | 20 | 1.40 | 0.503 | 0.112 | |||

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | |||

| Customize | Equal variances assumed | 40.042 | 0.000 | 3.746 | 33 | 0.001 | |

| Equal variances not assumed | 4.081 | 29.728 | 0.000 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, X.; Chen, W.; Kang, J. Art in the Age of Social Media: Interaction Behavior Analysis of Instagram Art Accounts. Informatics 2019, 6, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6040052

Kang X, Chen W, Kang J. Art in the Age of Social Media: Interaction Behavior Analysis of Instagram Art Accounts. Informatics. 2019; 6(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Xin, Wenyin Chen, and Jian Kang. 2019. "Art in the Age of Social Media: Interaction Behavior Analysis of Instagram Art Accounts" Informatics 6, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6040052

APA StyleKang, X., Chen, W., & Kang, J. (2019). Art in the Age of Social Media: Interaction Behavior Analysis of Instagram Art Accounts. Informatics, 6(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6040052