Abstract

Gamification has recently been presented as a successful strategy to engage users, with potential for online education. However, while the number of publications on gamification has been increasing in recent years, a classification of its empirical effects is still missing. We present a systematic literature review conducted with the purpose of closing this gap by clarifying what effects gamification generates on users’ behaviour in online learning. Based on the studies analysed, the game elements most used in the literature are identified and mapped with the effects they produced on learners. Furthermore, we cluster these empirical effects of gamification into six areas: performance, motivation, engagement, attitude towards gamification, collaboration, and social awareness. The findings of our systematic literature review point out that gamification and its application in online learning and in particular in Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) are still a young field, lacking in empirical experiments and evidence with a tendency of using gamification mainly as external rewards. Based on these results, important considerations for the gamification design of MOOCs are drawn.

1. Introduction

It is often stated that gamification is a winning approach to ‘motivate’ people. Despite this belief, and broad field of application, its empirical validation is still to be proven. Furthermore, the field lacks an understanding of the main effects of gamification on short-, middle- and long-term. Gamification design, implementation and effectiveness are related to the audience and the context of application; nevertheless, a generalisation and analysis of current results and studies is needed to further improve the field. In order to be effective, designers of gamification need to be aware of what the outcome/s of a specific game element could be in a certain scenario and audience. This systematic literature review is a contribution to the field by providing an overview and map of the game elements most used in online learning environments, including Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), and their empirically proven effect/s on human behaviours.

The focus on online learning and MOOCs is due to the fact that online learning in general has several points in common and a number of differences with MOOCs in particular. To some extent, the latter can be seen as a subcategory of the first. However, MOOCs are different from online learning because they can help to scale up open learning opportunities [1]. MOOCs, taking advantage of cutting-edge technologies and the Internet, are reaching a massive audience and, until the recent past, they were free [2]. The MOOC phenomenon exploded in 2012, which was declared the year of MOOCs [3]. In almost the same period, in 2011, the gamification phenomenon reached its first peak, with the elaboration of the most known definition elaborated by Deterding et al. [4] (‘gamification’ consists of the transfer of game design elements to a non-game scenario). Since then, gamification has been applied to different fields (see Section 2); however, probably due to the concurrent development of both MOOCs and gamification, there are few empirical applications of gamification to MOOCs.

Despite this yet scarce implementation of gamification in MOOCs, there are several limitations in the current MOOC design for which gamification could be beneficial. High dropout and low completion rates, and a lack of learner engagement are widely presented in the literature as MOOC drawbacks [5]. Gamification could be adopted to increase the level of MOOCs users’ engagement, in addition to enabling users to achieve their own goals within a MOOC scenario. Hence, recent studies [6,7] suggest that completion rates alone are not a useful indication of MOOC success, but that participants’ goals and intentions also need to be considered [8]. By applying gamification to MOOCs, users could build their own plan and fulfil their personal goals within the course, and the deployment of game elements within MOOC environments could additionally increase the engagement of their users. Games, in particular Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs), are an example of highly engaging, scalable, though still highly personalised, user experiences [9]. Looking at games can be an option to find those elements that can be transferred to online learning, and more specifically to MOOC environments, with the aim of overcoming the drawbacks highlighted above. However, as mentioned above, there are still only a few examples of empirical studies of gamified MOOCs, thus, in this study, we expanded the investigation by looking also at online learning, which faces similar challenges, i.e., students’ dropout [10] and lack of engagement due to the development of feeling of isolation [11]. In this perspective, after having detailed the state-of-the-art of the gamification of MOOCs, the main research questions (Q) of this systematic literature review will be addressed:

- What are the gamification elements mostly used in online learning environments?

- What are the effects of these game elements on learners’ behaviour in online learning environments?

- What factors need to be considered for designing effective gamification of online learning environments, specifically MOOCs?

In an attempt to answer these questions, the paper is structured as follows: first, related works are presented, with a focus on the application of gamification of MOOCs as an emerging application field for gamification but still too young to be investigated in this work for its lack of empirical focus, then the method of data collection and analysis of this systematic literature review is detailed, together with the results consisting of the answers to the above reported research questions (Q1 and Q2). The study is rounded off by replying to Q3 and summarising our conclusions, declaring the limitations of this study and introducing our planned future work.

2. Related Works

Gamification effects have been investigated in several domains [12], such as banking [13], trading [14] the medical field [15,16,17], marketing [18,19] or with the purpose of facilitating annoying tasks [20,21]. According to Dicheva et al. [22], the sector in which gamification has been applied the most is education. In education, several literature reviews have been conducted to describe its state-of-the-art [22,23,24]; to report on the game elements most used in education [25]; to give an overview on the available gamification design frameworks [26]; to investigate the effects of gamification on students in face-to-face and blended situations [27,28,29,30].

Several systematic literature reviews, similar to this study, have been conducted to report on the effects of gamification in online educational settings [31,32,33]. From these, it is possible to draw the following conclusions: even though the number of publications on the use of gamification in education has increased, the field suffers from (1) a lack of “true empirical research on the effectiveness of incorporating game elements in learning environments” (p. 83), (2) inadequate “methodology used in most of the empirical settings to test the effects of game elements” ([22], p. 83) and (3) “heterogeneous study designs and typically small sample sizes, which highlight the need for further research” ([34], p. 1). However, despite all these lacunae, gamification has been judged to be a field with potential, a didactic strategy that if well designed and implemented can really give a boost to users’ engagement and motivation.

As far as the investigation of gamification in MOOCs is concerned, several (recent) literature reviews [35,36,37] report that the field is still developing and lacks empirical studies. Thus, the majority of the papers available are conceptual [6,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. However, by digging into the literature, we found a few studies, and four of these corresponded to our selection criteria (see Table 1). The first is Chang and Wei [46], which represents a first attempt towards the empirical investigation of the gamification of MOOCs. This study focuses on identifying the most suitable game elements to engage students in MOOCs in two steps. Firstly, by conducting a focus group with 25 frequent MOOC users, aimed at collecting the game elements that could trigger the engagement of users in an online setting like an MOOC. The results of this first step was a list of 40 game elements. Secondly, the authors ran a survey aimed at assessing the game elements (40) for their level of engagement (the survey involved 5020 MOOC learners). As a result of the survey data analysis, 10 game elements (virtual goods, three different types of points, leaderboards, trophies and badges, peer grading, emoticon feedback and two types of games) were identified with the highest level of engagement, as chosen by the majority of the survey participants [46]. Unfortunately, we could not find a follow-up study more directed to experimentally validating the hypothesis that these 10 game elements impact MOOC learners’ level of engagement.

Table 1.

Criteria for paper selection (steps two to five of the five steps of the systematic literature review performed, omitting the keyword selection).

The second study from the same year is Borras-Gene et al. [47]; they used the platform MiriadaX, for the implementation of their gamified cooperative MOOC (gcMOOC). Several external software programs were used to manage the reinforcement of social aspects of the course, such as Instagram, Google Hangouts and Google+; the game elements (badges) were also not integrated into the platform but issued externally using Mozilla Open Badges. The data collected were both qualitative and quantitative and, in the study, there are not explicit references to A/B testing or the division of participants in gamified cooperative (gc) and plain conditions in the description of the method applied. The conclusions presented are, however, promising for the application of gamification in an environment such as MOOCs.

The third is Binti Mohd Nor Hisham and Sulaiman [48], who conducted an experimental study. The authors [48] deployed the game elements scores, likes (a form of social scoring, similar to the one used in Facebook), progress bars, group activities and rewards, and badges with the purpose of increasing MOOC users’ engagement and completion rates. This study involved a total of fifty-three participants, divided in a control group (non-gamified, thirty-one users) and experimental group (gamified, twenty-two users). By comparing the two groups, the results show that there was no significant difference for engagement, but more participants in the experimental group completed the course compared to participants in the control group, therefore gamification impacted positively on completion rates.

The fourth study is from Navío-Marco and Solórzano-García [49], which is a data-driven exploratory study, that involved 3250 participants, investigating how gamification impacted course completion rates. The MOOC was gamified by using badges and ‘karma points’, a kind of social oriented scoring that works similarly to the ‘likes’ described above. MOOC participants, instead of assigning ‘thumbs up’, used these points. In order to determine the effects of their gamified intervention, Navío-Marco and Solórzano-García [49] did not perform an experimental study but via the log data they described and categorised all the participants actions. Their analysis shows that there was a relation between ‘karma points’ and completion rates: the participants with higher completion rates were the ones with higher ‘karma points’.

Based on what has been presented in this paragraph, it is then possible to sum up the following: gamification of MOOCs is a novel field and, from the few empirical studies available, it can be observed that gamification is mainly implemented as a strategy to tackle the MOOCs’ drawbacks previously described (completion rate and engagement). The game elements implemented are mainly external rewards, i.e., points, badges and scores. Therefore, a preliminary conclusion could be that the field ’gamification of MOOCs’ needs the support of all its researchers and developers to grow and establish empirical evidence. As a consequence, the field needs studies designed, conducted and analysed with rigorous experimental methodologies. Aware of this gap, knowing that gamification is not extensively applied to MOOCs yet, we aim to investigate the effects of gamification in online learning environments and explore if there are some lessons learnt that can be transferred to the MOOC scenario.

3. Methods and Data Collection

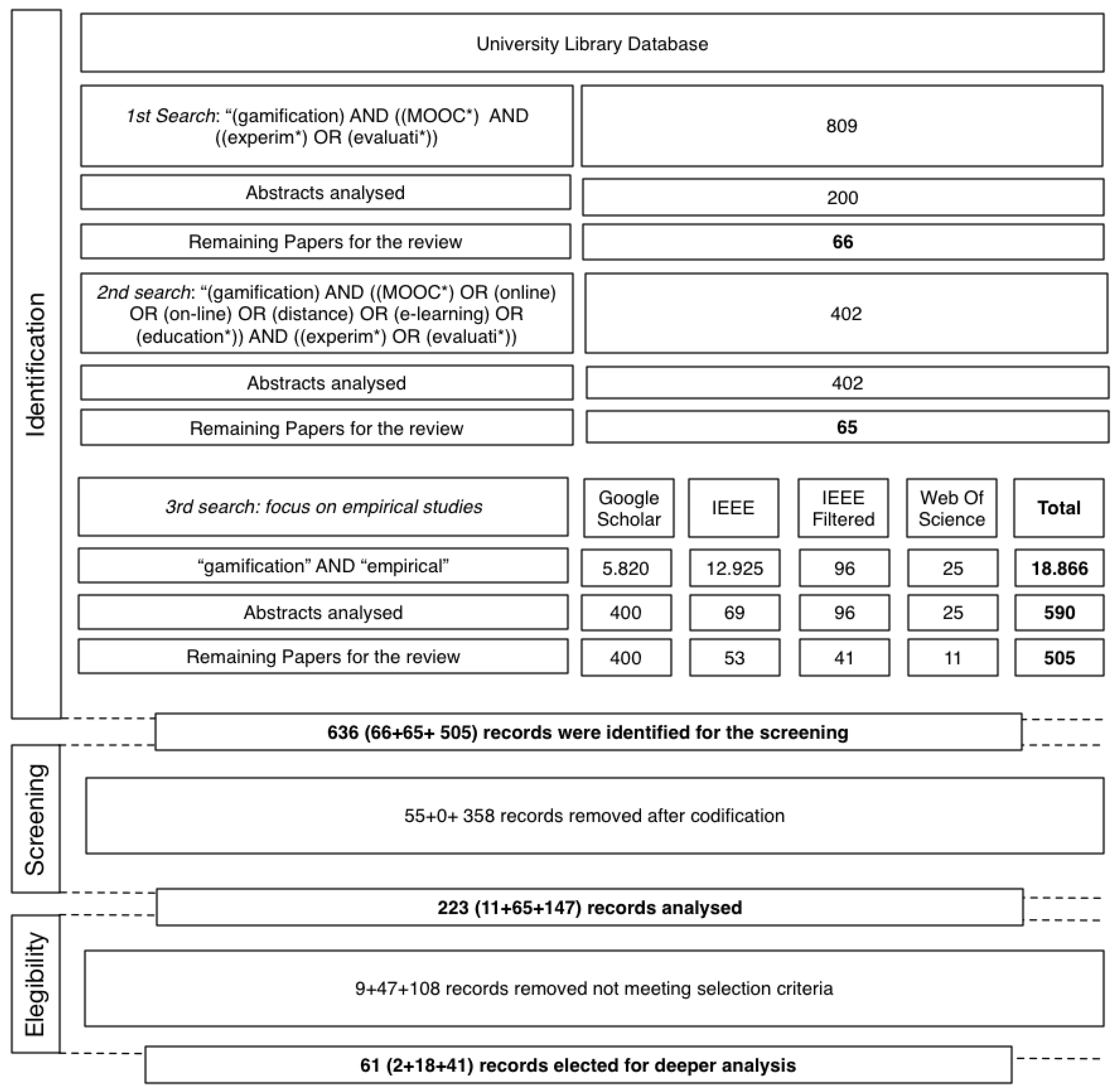

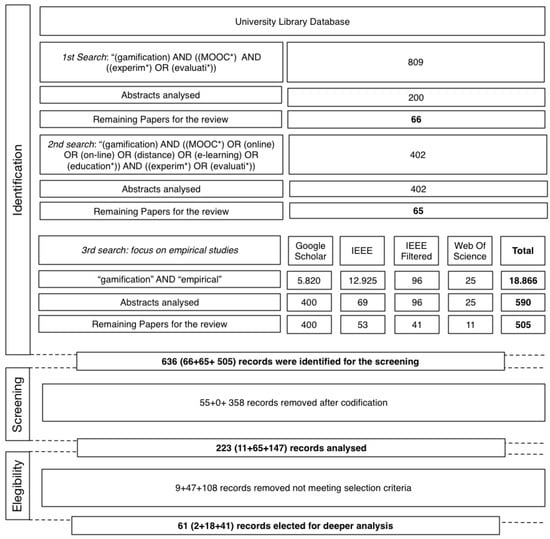

This systematic literature review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [50], represented and described below (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic literature review process according to PRISMA.

Step 1—Find the right keywords combination

By analysing several literature reviews in the field of Gamification of MOOCs, it became clear to us that there is a lack of empirical works. The few empirical studies available are dated back to very recent years. Therefore, we chose to perform a search aimed at identifying empirical studies on gamified MOOCs and narrow down the time span to the last year (from January 2018 to April 2019). The database used for the search was the university’s digital library, which enabled us to simultaneously access several databases: ACM Digital Library, EBSCO, SAGE journals, ScienceDirect (Elsevier), Taylor & Francis Online, Wiley Online Library, Web of Science, Google Scholar, IEEEXplore, Springer Link (and a lot more). The keywords combination applied for this query was “(gamification) AND ((MOOC*) AND ((experim*) OR (evaluati*))”, where the first two terms refer to the field of interest, and the other two to the study types we aimed to analyse.

As explained earlier, although our focus is on MOOCs, due to the limited number of empirical studies, this systematic literature review also investigates the effects of gamification applied in online learning environments. Therefore, we have included the terms ‘online’, ‘e-learning’ and ‘distance’, resulting in the following keyword combinations “(gamification) AND ((MOOC*) OR (online) OR (online) OR (distance) OR (e-learning) OR (education*)) AND ((experim*) OR (evaluati*))”. In addition, this time we used the university database, filtering the search for the period (January) 2014 to (December) 2018.

Finally, to be sure to gain a high coverage of all available articles in the literature, we have decided to perform a query on those databases that, according to our university library, contained the most records, which were: Google Scholar, IEEE and Web of Science. In this case, we opted for a broader keywords combination: “Gamification AND Empirical”, removing any reference in the query to the field of application (i.e., ‘MOOC’, ‘online’, ‘e–learning’, etc.) (the keyword combinations: ‘gamification AND effect’ and ‘gamification AND experiment’ were also used, but the results were not satisfying). The period considered was, as above, (January) 2014 to (December) 2018.

Steps 2 to 5

Figure 1 represents and summarises step 2 identification, step 3 screening, step 4 eligibility, and the final step 5, in which the number of papers included in this systematic literature review is identified. To assure the quality of the data analysis and avoid biases due to personal interpretation, the process described in Figure 1 was double-checked by the other two authors of the manuscript.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this systematic literature review are detailed in the following Table 1.

4. Data Analysis and Results

The data analysis and results section is structured in accordance with the research questions. Q1 and Q2 will be addressed in the remainder of this section, while Q3 is addressed in the discussion section. A precise overview of the studies, methods used, samples involved and environments, is presented in the Appendix A, Table A1.

4.1. Q1: What Are the Game Elements Most Used in Online Learning Environments?

The lack of empirical studies within MOOCs, and the need to contribute to the field with more awareness of what a single game element or a combination of those can produce as an effect on learners’ behaviour, resulted for us in also including in our review studies implemented in e-learning and online learning scenarios (see Appendix A, Table A1). By analysing these studies, we tracked the game elements used: there are 24 (see Appendix A, Table A2), some of them have been studied in isolation, others in combination. More specifically, they are:

- Badges, which are external rewards delivered to users once a goal is accomplished. They have been analysed in 22 studies [47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]

- Leaderboards, a game element based on social comparison that enables a user to understand how s/he is performing (showing the score and/or the position) in relation to others and the leader; this has been adopted and investigated in 15 studies [51,52,53,54,55,58,59,60,62,63,70,72,73,74,75]

- Points that are “a numerical representation of player success” [76]; in the literature, authors also refer to these using the terms ‘score’ or ‘ranking’. They have been examined in 12 studies [52,53,59,61,62,63,66,67,68,69,71,72].

- Feedback can be defined as information delivered to users related to their progress, achievements, issues, or other aspects of their activities. Feedback can take several forms and can be delivered asdirect or indirect information. Sometimes, a clue (information on how to solve a quest) can also be considered feedback. This game element can be used in combination with other game elements, for instance with leaderboards and badges. We tracked six studies related to feedback [61,66,67,70,71,77].

- Challenges can appear in the form of quizzes or problems to be solved, in solo orteam mode. They can be related to levels or/and to missions. We recorded the use of this game element in five studies [53,54,55,66,72].

- Likes, social features are widely spread on social networks, such as Facebook, which implies supporting what another user communicates via a thumbs up (or smileys). Four of the papers found refer to them [47,53,58,61].

- Communication Channels “are the medium and the methods players can use to send messages to other players” [76], an example in this sense are chats. These have been investigated in four studies [51,53,54,61].

- Narratives consist of using stories to pass information and intrigue users, often confused with storytelling, which implies using a character to tell a story. We found that it has been used in four of the studies [67,68,72,78].

- Levels are strictly related to goals and have different degrees of difficulty. To move up a level, it is generally necessary to reach (complete) all the goals of the current level. This game element has been empirically investigated by four studies analysed [54,63,67].

- Progress bars give the user information about his/her own improvement. This game element has been examined by two studies [47,71].

- Teams, referring to working in a team, collaborating with the members within; this was used by two studies [47,72].

- Agent, not to be confused with avatar or profile, is a virtual character by the system (not by the user). In the literature, we have found two studies that implemented agent [71].

- Medals, a form of external reward that have been investigated in two studies [55,69].

- Avatar is the virtual version of the player and has been introduced and investigated in two studies [62,79].

- Trophies are another form of reward for something users have achieved, like solving a level or overcoming a challenge. They are considered in two studies [54,55].

- Time limit considered by [62,70].

- Task, which is generally connected with the previous one, but it has been considered by different authors [79].

- Virtual Currency is a type of reward in the form of virtual money; it has been investigated by [79].

- Personalising features; refers more to features typical of games in which the player can personalise the look and the outfit of the avatar/character; these were discussed in one study [69].

- Mission, which is a type of challenge, generally connected with task and time limit, and it has been investigated by [69].

- Replayability is the possibility given to users to re-do an action if, at the first attempt, he/she did not succeed. It was investigated by one study [65].

- Goal Indicators can be combined with several game elements such as levels and missions, and it has been examined by [67].

- Competition, usually within teams and or player vs. player; this has been presented in one study [69].

- Win State very typical of the game world, but it has been considered only by one recent study [72].

4.2. Q2: What Are the Effects of These Game Elements on Learners’ Behaviour in Online Learning Environments?

A query of the literature has been done to close the identified gap related to the investigation and definition of what the effects of gamification are on users’ behaviour within online environments. From our analysis, we identified mainly six categories of effects of gamification on learners’ behaviour and characteristics: (1) performance; (2) motivation; (3) engagement; (4) attitude towards gamification; (5) collaboration; and (6) social awareness. In the following section, the effects per category are described and then summarised in the Appendix A, Table A3 and matched with the game elements in Table A4.

- PerformanceGrant and Betts [57] examined the influence of badges on (1,295,620) users’ performance (activity in web forums); the positive impact of badges on users’ performance were investigated by Hakulinen et al. [58]’s study, who investigated badges, within an online learning environment (involving 281 students) and their impact on the carefulness of the performance (looking at significant differences in terms of time spent per submission and number of attempts per exercise), highlighting the fact that badges can affect students’ behaviour in terms of time needed to perform and precision in the performance increasing students’ carefulness. “Students in the treatment group spent more time per submission on average” (p. 23), showing a higher level of carefulness compared to their colleagues in the control group [58]. In a similar scenario, an online learning course (involving 150 students), Kyewski and Krämer [64] investigated the effects of badges on learners’ performance, and, in contrast to the studies previously detailed, recorded a negative effect of badges on learners’ performance.Leaderboards were the focus of studies by Landers and Landers [75] and Bernik et al. [51], both implemented in an online learning scenario. The first (involving a total of 86 participants) aimed to study the effect of the game element leaderboard on learners’ academic performance, looking at the amount of time spent on a task (consisting of a wiki project). As a result, users in the treatment group (with leaderboard) increased their time-on-task performance [75]. The second, Bernik et al. [51] (involving a total of 55 students), looked at performance comparing the achievements of the control and treatment groups. Students in the treatment group had much better achievements, when comparing the average results in the post-tests performed by the two groups [51].The single game element narrative was studied by Armstrong and Landers [78], who tested how users would perform and react to gamified training, finding that participants in the gamified condition reacted better to the training than their colleagues in the control (non-gamified) condition [78].Several studies have investigated the effects of gamification on users’ performance by combining different game elements. Four game elements: challenges, leaderboards, trophies and medals were implemented by Domínguez et al. [55] within an e-learning platform. To study the effects of their plugin on students’ learning performance, they compared the scores achieved in several activities by participants in both control (non-gamified) and treatment (gamified) groups. The data analysis showed that students in the treatment group performed better than those in the control group in the initial activity, and in the majority of the assignments. Negative effects of the gamification approach were instead reported for the final examination, where students in the treatment group registered a significantly lower score [55]. Tsay et al. [70] also opted for four game elements: immediate feedback; badges; leaderboard and time limits. By comparing the scores of the two groups (control-non-gamified and treatment-gamified), the authors highlighted that students in the gamified condition performed better (higher score) than their colleagues in the control group. Finding that their performance was mediated by their level of engagement, the students in the gamified condition were more engaged and therefore had better performance compared to their colleagues in the control condition [70].The study of De-Marcos et al. [79] aimed to determine which of these five different conditions: plain, educational game, gamification, social networking and social, was the most effective on learning performance (75 undergraduate students were involved). Participants, distributed into the different conditions, were asked to perform five different tests (word processing, spreadsheets, presentation, databases and final examination). In the comparative analysis, it was demonstrated that all the experimental conditions outperformed the control group in three of these tests (word processing, spreadsheets and presentation). The authors concluded that gamification impacts on learning performance when it is combined with social approaches [79]. Similar conclusions were drawn by Krause et al. [62], who showed that social gamification increases learning success (see details of this study in the engagement section).Long and Aleven [65] studied the effect of a gamified Intelligent Tutoring System (ITS) on students’ learning and enjoyment (involving 267 students). The game elements selected were: rewards (Rwd) for good performance; and replay (RePl), the chance to complete a task again (in this case a problem already solved). The four different conditions were analysed combining the two game elements (RePl + Rwd; No-RePl + Rwd; RePl + No-Rwd; No-RePl + No-Rwd) and the most effective combination for students’ learning was replay without rewards (RePl + No-Rwd) [65]. Students under the condition with both replay and rewards activated, performed significantly worse than their colleagues exposed to the other three conditions of the study. No significant effects were found when comparing the two groups in terms of enjoyment [65].Two studies recorded the effects of gamification on performance in terms of goal commitments. The first by Landers et al. [74] reported on a quasi-experiment (involving 339 university students), to better understand how leaderboards can enhance user performance and influence goal commitment, or vice versa [74]. Participants were randomly assigned to one of five conditions (do-your-best, easy goal, difficult goal, impossible goal and leaderboard). With their study, Landers et al. [74] demonstrated that the leaderboard condition was the most influential and that the goal-setting theory is suitable to understand and explain leaderboard effects on users’ performance: “commitment moderates the success of leaderboards as goal-setting theory would predict” ([74], p. 5). In accordance with the goal-setting theory [80], goal commitment and performance are directly related to each other, “goals are only effective if people are committed to them, and performance is maximised when individuals are committed to difficult, specific goals” ([74], p. 5). The results showed that users in the leaderboard condition performed better than those in the other conditions. Participants in the leaderboard condition were “likely to target the top or near-top goals presented on that leaderboard, even without specific instructions to target those goals” ([74], p. 6). The second study, conducted by Hakulinen and Auvinen [81], focused more on goal orientation. The authors studied the relationship between the achievement of badges and goal orientations, they hypothesised “that students with different goal orientation profiles respond differently to badges” ([81], p. 9). Their study was conducted in an online environment (involving 278 students) divided into a control (non-gamified) and a treatment (gamified) group. They “found no statistically significant differences in the behaviour of the different goal orientation groups regarding badges. However, their attitudes towards the badges varied” ([81], p. 16).

- MotivationThe effect of rewards in the form of badges on learner motivation was studied by Kyewski and Krämer [64]. They first measured the participants’ level of the intrinsic motivation before the intervention. Subsequently, they checked: (1) if the intrinsic motivation level changed in relation to participants earning the badge; (2) if the level of intrinsic motivation changed compared to the beginning (higher intrinsic motivation for those who had a low level at the beginning and vice-versa, lower for those who declared a high level of intrinsic motivation). No effects of badges were found on students’ intrinsic motivation. These results contradicted a study conducted in similar conditions (participants from the university level, working in an online learning environment) by Hakulinen et al. [58], reporting that the majority of participants declared being motivated by badges and concluding that “achievement badges seem to be a promising method to motivate students” ([58], p. 18). The positive effect of badges on learners’ motivation was confirmed by Gooch et al. [56], who conducted their study in Moodle but with a small group of children with a learning disability (dyslexia). Based on their findings, badges significantly improved students’ motivation [56].Dyslexic students (40 were involved) were also the target audience of Saputra [67]’s study, who adopted the following game elements: narrative, goal indicators, levels, scores, feedback and badges, highlighting that these game elements produce positive effects on students’ engagement, enjoyment and motivation in the short term. A longitudinal study instead was conducted by Hanus and Fox [60] to assess the effects of badges and leaderboards on students’ motivation, as well as on social comparison, effort, satisfaction, learner empowerment, and academic performance. Two classes (gamified and not-gamified) were set up and the results showed that, over time, students in the gamified course presented less motivation, satisfaction and empowerment compared to those involved in the non-gamified class [60].The study of Utomo and Santoso [71] was implemented in an online learning environment to test the effects of a ‘pedagogical agent’ on students’ motivation and behaviour towards learning. The agent activity was enhanced with the adaptation of some game elements, such as progress bar, badges, scores and feedback. Based on students’ evaluation, the authors concluded that personalised feedback in real time boosted learners’ motivation “toward active learning behaviour” ([71], p. 7). Badges, as well as points and leaderboards, were used also by Huang and Hew [59], who gamified an SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) course in ‘Moodle’, showing that badges and leaderboards motivated most of the learners. Points engaged students and stimulated them to undertake challenging tasks and extracurricular learning, while “learners in the control group did not attempt any challenge” [59]. The same game elements were implemented in LOPUPA (Learning On Projects of United Promotion for Academia), a gamified platform proposed by Kuo and Chuang [63] implemented with the purpose of engaging and motivating online academic dissemination. Based on the data collected via the platform (as well as google analytics), and the feedback given by participants by filling in a questionnaire, the authors showed increased engagement and motivation of the participants that used the platform [63]. Similar conclusions were reached by Domínguez et al. [55] who, in their study, also investigated the effect of their gamification design, described above, on students’ motivation, stating that “gamification in e-learning platforms seems to have the potential to increase student motivation, but it is not trivial to achieve that effect, and a big effort is required in the design and implementation of the experience for it to be fully motivating for participants” (p. 391).

- EngagementKyewski and Krämer [64] found that earning badges in an online learning environment did not increase students’ level of activity, which was used as a measure of engagement. Furthermore, data “revealed that students in the no-badge condition who did not earn badges were even more active than students in the gamification conditions” ([64], p. 32). This contradicts previous research findings, such as those reported by Sitra et al. [68], suggesting positive effects of badges on students’ engagement, even though they tested it within a different population (small number of students with special needs), using an LMS system-Moodle similar to Kyewski and Krämer [64]. Badges as well as narrative, score/ranking, levels, and quests are covered in the study of [69]. They aimed at investigating whether these game elements affect learners’ motivation and engagement on a peer assessment platform. By comparing the results of control and treatment groups, they found that the number of elaborated essays as well as the number of corrected essays were higher for participants in the treatment group. Therefore, the data indicated that gamification stimulated students to use the platform more, thus enhancing engagement [69].The following three studies underlined how the ‘social factor’ is important for engaging students. Firstly, Krause et al. [62] set up three conditions in ‘Moodle’ (plain–no game elements, game–with game elements, social-with social game elements). In particular, the game condition consisted of implementing, in an online environment (Moodle), game elements such as: avatars, badges, points, leaderboards and time limits. The social-game condition included all the game elements listed above and in addition integrated social game elements encouraging competition among students, also in remote mode, via pre-recorded actions, mainly by using the leaderboard and mechanism of social comparison. The purpose was to understand the differences (if any) between gamification and social gamification on students’ retention and learning success. The data showed that learners in the social game condition were more engaged compared with their colleagues in the plain condition, and the social game elements enhanced gamification effects on retention and success [62]. Secondly, De-Marcos et al. [54] set up a quasi-experimental design with five conditions (control group, non-gamified, gamified, social non-use, social use) with the purpose of understanding the effects of ‘social networking’ and ‘gamification’ on students’ academic achievement, engagement and attitude in an undergraduate course [54]. The game elements implemented were: badges, challenges, leaderboards, levels, trophies and forum. The data revealed that both gamification and social networking were perceived positively by students, therefore an improvement of participants’ attitude towards these approaches was recorded, while no significant statistical differences were found in students’ academic achievements or engagement [54]. Thirdly, Mazarakis [77] conducted a study on using feedback mechanisms, testing four types of feedback to increase user engagement, i.e., participation in the course wiki: (1) gratitude feedback: this expressed thankfulness without giving any further information to the users, (2) historical: this gave information about users’ activities and contributions, (3) ‘relative ranking’: showing relative user rank, and (4) ‘social ranking feedback’: this aimed at providing information about the points and activated competition via ranking comparison. The results showed that providing feedback mechanisms can enhance participation. Among the feedback mechanisms tested, the one enabling social comparison (called ‘social ranking feedback’) was the most effective feedback [77]. More focused on the attitude towards gamification is the study of Aldemir et al. [72], included in this dimension because it deals also with the aim of increasing students’ perception of others within an online educational scenario. The study investigated in particular the participants’ attitude towards leaderboards, challenges, narratives, teams, badges (and rewards in general) win-states, points, and ‘constraints’, providing generally positive results and “insights about game elements integrated into a gamified course in both online and face-to-face sessions” ([72], p. 251).

- Attitude towards gamificationThe following authors: Bernik et al. [51], Hakulinen et al. [58], Aldemir et al. [72], whose work is already presented above, have also all studied the effects of their gamification designs on the attitude towards gamification, reporting all positive responses of the participants in this matter. In the same line is the study of [54], who in an online learning scenario set up a quasi-experiment with the purpose of studying the effect of social networking and gamification on student academic achievement, participation and attitude towards gamification. The participants were split into three conditions: gamification (114); social network (185) and control (75). In the gamified condition, the following game elements were displayed: badges, challenges, leaderboards, forum, levels and trophies. A survey was completed by both the experimental groups to assess learners’ attitudes towards gamification and social networks. The results showed a positive effect on users’ attitude towards gamification; no significant effects were found on performance improvement and neither on written examinations. Regarding academic achievement, it was better for the social network participants [54].

- CollaborationKnutas et al. [61] studied the effects of a gamified online discussion system on users’ collaborative behaviour and communication (involving 249 students). The system was used during an existing university course ‘introduction to programming’ for fourteen weeks. The major aim of the gamified online discussion system was to facilitate contributions for effective discussions. Therefore, to enhance peers’ contribution and communication, users were enabled to ‘like’ or ‘unlike’ the comments of their peers. In addition, a reward feedback system was implemented for the users who were contributing. To determine the effects of the described gamified online discussion system on users’ collaborative behaviour and communication, several tools were used, such as surveys, interviews and Social Network Analysis (SNA). From the data analysis, it was possible to conclude that the gamified online discussion system increased student collaboration and course communication efficiency by reducing response time to students’ questions. In particular, the survey showed that skilled students liked the gamification features (consisting of the discussion system and rewards) and Knutas et al. [61] concluded that the game elements stimulated users to contribute more by giving more answers and proposing more questions. Part of this dimension is also in the Aldemir et al. [72] study, described above, who point out that, in using the team game element, the balance of "the team skills" is important, enabling the right level of competition and collaboration within the team.

- Social awarenessTwo studies were dedicated to the “social awareness” that gamification can generate: Aldemir et al. [72], Christy and Fox [73]. In particular, [73] set up a study on leaderboards, aimed at investigating whether interaction with a leaderboard (with male vs. female leaders) produced effects in the social comparison condition or led to stereotype threats and effects on academic performance. Their data showed that “leaderboards appear to have inspired social comparison processes” (p. 74) more than ‘stereotype threats’ [73]. The second study by [72] adopted “teams”, another game element that can enable participants, in an online learning course, to be aware of the others and thus facilitate community building. Using the authors’ words: “Community-building process is affected by the interaction and relationship between teammates, implying that good communication facilitates community building. Another implication is that, the fewer people in a team, the easier it is to communicate; therefore, the teams should be small community building” ([72], p. 250). Based on the qualitative data collected by Aldemir et al. [72], participants reacted positively to this game element, with positive effects on learning achievement.

Several studies have analysed moderating factors of gamification effects, specifically considering gender, personality and lifestyle (work) of the participants. Pedro et al. [66]; Tsay et al. [70]; and Codish and Ravid [52] studied respectively whether gamification had different effects on female and male students; on participants with different lifestyles (part-time or full-time job); and on extroverts vs. introverts. It turned out that, according to Pedro et al. [66], males are more influenced by gamification (in particular by eternal rewards, such as: points, badges, feedback, scores and challenges) compared to females. However, the situation changes if the population works part-time, indeed according to the results of Tsay et al. [70]: “The gamified course […] was particularly beneficial to learners who were working part-time and female students” ([70], p. 32), while, according to Codish and Ravid [52], extroverts connect playfulness with badges, rewards and points while introverts tend to prefer an offline leaderboard.

5. Discussion

In this systematic literature review, we have investigated and reported on the effects that gamification can generate on human behaviour, within MOOCs and online learning environments. Three research questions have been addressed.

Q1 relates to game elements used most in online learning environments, which are, in order of frequency of usage: badges/rewards (most used); leaderboards and points/score/ranking. Addressing Q2, we clustered the effects of these game elements in six dimensions: performance, motivation, engagement, attitude towards gamification, collaboration and communication, and social awareness. We highlighted the application scenarios and characteristics of each study by underlining what type of effects a specific game element or combination could generate on users.

Both the game elements examined in the studies included in this systematic literature review and their effects have been matched and are presented in the Appendix A, Table A4. By correlating the game elements most used in online learning and the effects they generate on learners, it is possible to notice the following:

- Effects of badges/rewards are observed on motivation, attitude toward gamification use, and performance in terms of time management, engagement, emotional states, and enjoyment. Effects of badges may vary according to gender and personality, and, if perceived as controlling and restrictive, they may negatively affect motivation and engagement. They can be used to set clear goals or to stimulate social comparison, both variables that have a positive effect on performance (in the training field, specifically).

- Effects of leaderboards have been found on attitude toward gamification use, learning performance, performance in general, engagement, enjoyment, and goal commitment, by engaging students in difficult tasks. Effects generated by leaderboards vary according to personality. Just like badges, leaderboards can enable social comparison that can positively influence performance. More specifically, the game element leaderboards provides information about points, scored by users, which activates social comparison and competition among them and achieve, as effects, higher participation and engagement, in particular at the cognitive level [77].

- Effects of point/score/ranking have been reported related to motivation, attitude toward gamification use, learning performance, performance in general, engagement, enjoyment and emotional states. Effects of point/score/ranking may vary according to personality and gender. They can foster social comparison and thus also influence performance. Furthermore, the game element points/scores/ranking enhanced the level of users’ engagement so much that they were stimulated to undertake challenging tasks and target “top or near-top goals” in terms of difficulties [74].

In relation to the lessons learnt from the application of gamification to online leaning environments, transferrable to MOOCs and, therefore, Q3, the following considerations are made. First, the gamification of online learning environment design addresses similar problems that MOOCs have: motivation, performance, and engagement. Second, from the studies found, it is possible to highlight the multidisciplinary character of gamification and its design. The third and most important lesson learnt is that each game element “should be carefully chosen [...] to avoid gamification from being just unnecessary eye candy” ([81], p. 28). As in the MOOCs, field external rewards are largely used in online learning. While, on one side, they are easy to be implemented, it is important to keep in mind that their meaning and purpose can be easily misunderstood by the receivers Kyewski and Krämer [64]. Hanus and Fox [60] explained that, when an audience is already motivated, the reward strategy might be perceived negatively, “interpreted as controlling, causing students to feel less confident, to be less satisfied with the course, and to have less motivation to engage with the material” ([60], p. 159). This result is in line with the Cognitive Evaluation Theory (CET) [82], which predicts that external events can harm intrinsic motivation “based on whether individuals process those events as informational or controlling” ([60], p. 153). Therefore, if a reward, such as a badge, is used as mere ‘candy for the eyes’, then gamification could be far from beneficial.

Summing up, the following factors need to be considered in designing gamification for MOOCs:

A first “vital aspect of gamification design is the context of application” ([83], p. 3). In the framework of this study, the application scenario is MOOCs. MOOCs can appear in several formats, but they all have a common denominator: a massive audience, which implies an enormous differentiation in users’ culture, age, prior knowledge, background, languages, intentions, etc., all factors that need to be taken into consideration in designing an intervention within such an environment. The second factor is the problem, which determines the aim of the intervention: it can differ from case to case (and can be, for instance, related to lack of personalisation, of engagement, high user dropout rate, etc.). The third factor is the selection and the design of the most appropriate game elements in accordance with the problem to be addressed and the desired effect/s. In this case, the definition of a theoretical framework that supports the design of your game elements, as well as your approach will be of added value.

MOOCs are online learning scenarios, with their own peculiarities. These are due essentially to the massive audience and the technology used (platform) and its openness, implying with openness the degree of manoeuvre that designers and developers have in directly intervening on the platform, which is a factor that can drastically impact on the gamification design choices, the effectiveness of the implementation and the intervention in an MOOC scenario.

Last but not least, it is important to also consider the evaluation phase when designing the gamification of MOOCs (or other application scenarios). By conducting rigorous research in the field of gamification applied to online learning environments, the awareness about its potential and limits can be increased and the field can grow further.

6. Future Work

This systematic literature review had the general purpose of contributing to the field by increasing awareness about the empirically tested effects of gamification on human behaviour in online learning environments. To raise this awareness, the state-of-the-art in the ‘Gamification of MOOCs’ has been presented. Subsequently, the game elements most used in online learning scenarios (Q1) have been identified, and their effects on users’ behaviours (Q2). Then, the lesson learnt from online learning has been transferred to MOOCs and the steps needed to design gamification of MOOCs have been drawn up (Q3).

Our conclusion and analysis is in line with Nacke and Deterding [83], who underline that “gamification research is maturing ([83], p. 4), and there have been steps forward aiming at understanding the effects of gamification; however, “many studies are still to some extent comparing apples with oranges, testing different implementations of design elements with different effect measures” (p. 3). In relation to the design of gamification, other game design elements are introduced but still PBL (points badges and leaderboards) remain the favourite.

In our future work, we aim to conduct rigorous research with the aim of, from one side, contributing to the field with a framework on how to design proper gamification Antonaci et al. [42] and, from the other, on how to study the effects of our design on human behaviour, contributing to the growth of the field with empirical data and studies. Furthermore, we aim in future work to demonstrate that gamification can be applied in a more sophisticated way than just PBL, a gamified way that can be easily confused with a simple ’candy for the eyes’, and an external reward system that does not consider the variegated characteristics that an MOOC audience can have. More specifically, in our future studies, we aim to design an intervention, using gamification to tackle the problems we have identified in MOOCs (lack of engagement and goal achievement of MOOC users). From the literature, we could deduce that, to enhance engagement within an online learning scenario, the ‘social aspect’ plays a strategic role. In a recent study, Tseng et al. [84] analysed the social presence in games and the factors that make game communities powerful. In addition, they also underlined the factors that retain players in a specific group or ‘guilds’, which are: firstly, sense of community (membership, sense of belonging) that positively impacts retention and ‘relation switching cost’ [84]; secondly, interdependence that can be described as the “degree to which members in a community rely on each other to make decisions and take actions” ([84], p. 603). Hence, as future work, to address the lack of engagement of MOOC users, we aim to identify game elements that can generate a sense of community and interdependence. Our hypothesis is: if MOOC users generate a sense of community, then their level of engagement and retention will increase.

As far as the enhancement of MOOC users’ goal achievement via gamification is concerned, in previous studies, we have identified the Implementation Intention theory by Gollwitzer [85] as promising for designing our game element/s. This theory shows that, if a person makes a precise plan (detailing the when, what and how of reaching her/his own goal), taking also into account what to do if an inconvenience occurs, the chance of reaching her/his goal/s will be higher compared with people that only have an intention [86]. Our hypothesis is if MOOC users have the chance to make a plan, according to the implementation intention theory, then their goal achievement will be higher compared with users that do not make a plan. Considering that, in this study, none of the studied game elements enable MOOC users to develop a sense of community or implement an intention, we will expand our analysis looking at game elements collections such as Björk and Holopainen [76] and type of games such as Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) that might match our needs. Once identified, we will validate the game element selection involving experts from the fields of game design, pedagogy and instructional design. In the end, an experimental study will be set up based on our hypothesis to test, analyse and validate the empirical effects of all our selected game elements on engagement (sense of community) and goal achievement of our MOOC learners.

7. Limitations of This Study

Several shortcomings can be identified with two major limitations: firstly, the fact that a very limited number of studies were available in the literature with a specific focus on gamification of MOOCs. Secondly, to map the effect of a specific game element in a certain scenario, a meta-analytic approach would have been more suitable. However, due to the diversity in the studies, the sample and the methodologies applied, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis that could determine more precisely the effects of each game element in an online scenario.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A., R.K. and M.S.; the methodology used was agreed upon by the three authors; formal analysis, resources, investigation, data curation and writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, R.K. and M.S.; visualization and validation, A.A.; supervision, R.K. and M.S. For term explanation, check http://img.mdpi.org/data/contributor-role-instruction.pdf.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This research has been conducted in the framework of a PhD study, partially founded by Erasmus+ projects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MOOCs | Massive Open Online Courses |

| MMORPGs | Massive Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games |

| Q | Research Question |

| MMOGs | Massive Multiplayer Online Games |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Methods used in the studies included in this systematic literature review, with details about sample and environment gamified.

Table A1.

Methods used in the studies included in this systematic literature review, with details about sample and environment gamified.

| Study | Method | Sample | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bernik et al. [51] | Pre-post survey | 55 (28 + 27) | e-learning |

| De-Marcos et al. [53] | Experimental | 75 | e-learning |

| De-Marcos et al. [54] | Quasi- exp | 318 (62 + 111 + 146) | e-learning |

| Domínguez et al. [55] | Quasi- exp | 173 (62 + 111) | e-learning |

| Borras-Gene et al. [47] | Mixed Methods | 3866 | MiriadaX |

| Gooch et al. [56] | Pre-post tests | 22 (10 + 10 + 2) | ClassDojo |

| Armstrong and Landers [78] | Experimental (two courses compared) | 273 | e-learning |

| Hakulinen et al. [58] | Experimental | 281 | online learning |

| Christy and Fox [73] | Experimental | 76 | online |

| Aldemir et al. [72] | Empirical (observation, interviews, documents) | 118 | e-learning |

| Huang and Hew [59] | Quasi- exp | 40 (21 + 19) | online learning |

| Knutas et al. [61] | Empirical (SNA, survey, interviews) | 249 | online learning |

| Krause et al. [62] | Experimental | 206 (71 + 67 + 68) | Moodle |

| Kuo and Chuang [63] | Empirical (surveys, web analytics) | 73 | LOPUPA |

| Kyewski and Krämer [64] | Experimental | 126 | Moodle |

| Long and Aleven [65] | Experimental | 190 | online learning |

| Utomo and Santoso [71] | Empirical (questionnaire and focus groups) | 31 | Moodle |

| Tsay et al. [70] | Empirical (two versions of the course compared) | 136 | Moodle |

| Pedro et al. [66] | Empirical (questionnaire) | 16 | E-Game |

| Saputra [67] | Empirical (observation and questionnaire) | 40 | e-learning |

| Sitra et al. [68] | Case Study | 5 | Moodle |

| Tenorio et al. [69] | Experimental | 32 | MeuTutor |

| Mazarakis [77] | Experimental | 436 | online learning |

| Landers et al. [74] | Experimental | 240 | online learning |

| Landers and Landers [75] | Experimental | 109 | online learning |

| Codish and Ravid [52] | Empirical (questionnaire) | 102 (58 + 44) | online learning |

| Grant and Betts [57] | Experimental | 1,295,620 | Stack Overflow |

Table A2.

Map of the game elements most used in online learning environments.

Table A2.

Map of the game elements most used in online learning environments.

| Game Elements | No. of Studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| Badges/ Rewards | 22 | [47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] |

| Leaderboard | 15 | [51,52,53,54,55,58,59,60,62,63,70,72,73,74,75] |

| Points/Score/Ranking | 12 | [52,53,59,61,62,63,66,67,68,69,71,72] |

| Feedback | 6 | [61,66,67,70,71,77] |

| Challenge | 5 | [53,54,55,66,72] |

| Likes (social features) | 4 | [47,53,58,61] |

| Communication Channels | 4 | [51,53,54,61] |

| Narrative | 4 | [67,68,72,78] |

| Levels | 3 | [54,63,67] |

| Progress Bar | 2 | [47,71] |

| Teams | 2 | [47,72] |

| Agent | 2 | [71] |

| Medals | 2 | [55,69] |

| Avatar | 2 | [62,79] |

| Trophies | 2 | [54,55] |

| Time Limit | 2 | [62,70] |

| Task | 1 | [79] |

| Virtual Currency | 1 | [53] |

| Personalising Features | 1 | [79] |

| Missions | 1 | [69] |

| Replayability | 1 | [65] |

| Goal indicators | 1 | [67] |

| Competition | 1 | [69] |

| Win State | 1 | [72] |

Table A3.

The users’ behaviour and characteristics affected by gamification.

Table A3.

The users’ behaviour and characteristics affected by gamification.

| Cluster | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Performance and time management | [51,53,55,57,58,62,64,65,70,75,78,81] |

| Performance and goal commitment | [74,75,81] | |

| Motivation | [47,55,56,58,59,60,63,64,66,67,69,71] | |

| Engagement | Engagement | [51,58,59,61,63,64,68,69,70,77] |

| Retention | [62] | |

| Enjoyment | [52,65,67,68,78] | |

| Attitude towards gamification | [47,51,54,58,72] | |

| Collaboration (and communication) | [61,72] | |

| Social awareness | Community building | [72] |

| Social comparison | [73] |

Table A4.

The game elements applied in online learning and their effects matched.

Table A4.

The game elements applied in online learning and their effects matched.

| Areas Impacted—Game Elements | Engagement | Engagement (Retention) | Enjoyment | Performance (Goal Commitment) | Attitude towards Gamification | Motivation | Collaboration (Communication) | Community Building | Social Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badges | [51,58,59,61,63,64,68,69,70,71,71] | [62] | [65,67,68] | [51,53,57,58,62,70] | [47,51,54,58] | [47,55,56,58,59,60,64,66,67,69] | [61] | ||

| Leaderboard | [59,63,70,72] | [62] | [52,53,62,70,72,74,75,81] | [51,54] | [55,59,60] | [73] | |||

| Points/scores | [59,61,63,69,72] | [62] | [68] | [51,53,62,71,72] | [51] | [52,59,66,67,69] | [61] | ||

| Feedback | [61,71,77] | [67] | [66,67,70] | [61] | |||||

| Challenges | [53,55,66] | [54,72] | [55] | [72] | |||||

| Likes (social features) | [53,61] | [47,58] | |||||||

| Communication Channels | [63] | [51,53] | [51,54] | [63] | [62] | ||||

| Narrative | [67,68,78] | [72] | [67] | ||||||

| Levels | [63] | [67] | [54] | [67] | |||||

| Progress bar | [71] | [47] | |||||||

| Profile Pages | [51] | [51,53] | |||||||

| Teams | [72] | [47] | [72] | ||||||

| Agent | [71] | ||||||||

| Medals | [69] | [69] | |||||||

| Avatar | [62] | [62] | |||||||

| Trophies | [53] | [54] | |||||||

| Time Limits | [62] | [62] | |||||||

| Task | [53] | [54] | |||||||

| Virtual currency | [53] | ||||||||

| Personalising Features | [53] | [54] | |||||||

| Mission | [69] | [69] | |||||||

| Replayability | [65] | [65] | |||||||

| Goal Indicators | [67] | [67] | |||||||

| Competition | [69] | [69] | |||||||

| Win State | [72] |

References

- Kalz, M.; Specht, M. If MOOCS Are the Answer, Did We Ask the Right Questions? Implications for the Design of Large-Scale Online-Courses; Maastricht School of Management: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kizilcec, R.F.; Piech, C.; Schneider, E. Deconstructing disengagement: analyzing learner subpopulations in massive open online courses. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, Leuven, Belgium, 8–13 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pappano, L. The Year of the MOOC. The New York Times, 14 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference on Envisioning Future Media Environments (MindTrek ’11), Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J.; Ruipérez-Valiente, J.A. The MOOC pivot. Science 2019, 363, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonaci, A.; Klemke, R.; Stracke, C.M.; Specht, M. Gamification in MOOCs to enhance users’ goal achievement. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Athens, Greece, 25–28 April 2017; pp. 1654–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderikx, M.A.; Kreijns, K.; Kalz, M. Refining success and dropout in massive open online courses based on the intention–behavior gap. Distance Educ. 2017, 38, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, J. MOOC completion and retention in the context of student intent. EDUCAUSE Review Online, 8 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kihl, M.; Aurelius, A.; Lagerstedt, C. Analysis of World of Warcraft traffic patterns and user behavior. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems, Moscow, Russia, 18–20 October 2010; pp. 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drachsler, H.; Kalz, M. The MOOC and learning analytics innovation cycle (MOLAC): A reflective summary of ongoing research and its challenges. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016, 32, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, N.; Dalton, A.; Grant, M. Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. J. Educ. Built Environ. 2010, 5, 27–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasurinen, J.; Knutas, A. Publication trends in gamification: A systematic mapping study. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 27, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.F.; Oliveira, A.; Costa, C.J. Playing seriously—How gamification and social cues influence bank customers to use gamified e-business applications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on the effects of gamification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.; Gregório, J.; Pinheiro, F.; Póvoa, P.; Da Silva, M.M.; Lapão, L.V. How can information systems provide support to nurses’ hand hygiene performance? Using gamification and indoor location to improve hand hygiene awareness and reduce hospital infections. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Edney, S.; Maher, C. Engagement, compliance and retention with a gamified online social networking physical activity intervention. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardi, L.; Idri, A.; Fernández-Alemán, J.L. A systematic review of gamification in e-Health. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 71, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Ahn, S.J.G. The Role of Gamification in Enhancing Intrinsic Motivation to Use a Loyalty Program. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 40, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Asaad, Y.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining the impact of gamification on intention of engagement and brand attitude in the marketing context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Opwis, K.; Tuch, A.N. Do points, levels and leaderboards harm intrinsic motivation? In Proceedings of the First, International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications (Gamification ’13), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–4 October 2013; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekler, E.D.; Brühlmann, F.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicheva, D.; Dichev, C.; Agre, G.; Angelova, G. Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Borges, S.; Durelli, V.H.S.; Reis, H.M.; Isotani, S. A Systematic Mapping on Gamification Applied to Education. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’14), Gyeongju, Korea, 24–28 March 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponetto, I.; Earp, J.; Ott, M. Gamification and Education: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Berlin, Germany, 9–10 October 2014; Volume 1, pp. 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nah, F.F.H.; Zeng, Q.; Telaprolu, V.R.; Ayyappa, A.P.; Eschenbrenner, B. Gamification of Education: A Review of Literature. In International Conference on HCI in Business; Nah, F.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, A.; Riera, D.; Gonzalez, C.; Arnedo-Moreno, J. A Literature Review of Gamification Design Frameworks. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-Games), Skövde, Sweden, 16–18 September 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakıroğlu, Ü.; Başıbüyük, B.; Güler, M.; Atabay, M.; Yılmaz Memiş, B. Gamifying an ICT course: Influences on engagement and academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida Souza, M.R.; Constantino, K.F.; Veado, L.F.; Figueiredo, E.M.L. Gamification in Software Engineering Education: An Empirical Study. In Proceedings of the IEEE 30th Conference on Software Engineering Education and Training (CSEE&T), Savannah, Georgia, 7–9 November 2017; pp. 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monterrat, B.; Lavoué, É.; George, S. Adaptation of Gaming Features for Motivating Learners. Simul. Gaming 2017, 48, 625–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. Gamified Modules for an Introductory Statistics Course and Their Impact on Attitudes and Learning. Simul. Gaming 2017, 48, 832–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work?—A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, M.C. Gamification: The effect on student motivation and performance at the post-secondary level. Issues Trends Educ. Technol. 2015, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looyestyn, J.; Kernot, J.; Boshoff, K.; Ryan, J.; Edney, S.; Maher, C. Does gamification increase engagement with online programs? A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsden, J.; Edwards, E.A.; Lawrence, N.S.; Coyle, D.; Munafò, M.R. Gamification of Cognitive Assessment and Cognitive Training: A Systematic Review of Applications and Efficacy. JMIR Serious Games 2016, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Wong, J.; Ebner, M.; de Koning, B.; Ebner, M.; Paas, F. Gamification in MOOCs: A Review of the State of the Art. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 18–20 April 2018; pp. 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Arranz, A.; Muñoz-Cristóbal, J.A.; Martínez-Monés, A.; Bote-Lorenzo, M.L.; Asensio-Pérez, J.I. How gamification is being implemented in MOOCs? A systematic literature review. In European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Lavoué, É., Drachsler, H., Verbert, K., Broisin, J., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Eds.; Springer: Tallinn, Estonia, 2017; Volume 10474, pp. 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.F.A.; Yusof, A.F.; Iahad, N.A.; Ahmad, N. The Implementation of Gamification in Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) Platform. In International Conference on User Science and Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Gené, O.B.; Mart, M.; Blanco, Á.F. Gamification in MOOC: Challenges, Opportunities and Proposals for Advancing MOOC Model. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 1–3 October 2014; ACM: Salamanca, Spain, 2014; pp. 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraguro-Bravo, R.A.; Jara-Roa, D.I.; Agila-Palacios, M. Techno-Instructional Application in an MOOC Designed with Gamification Techniques. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Ecuador, 30 March–1 April 2016; pp. 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, M.A.A.; Toda, A.M.; Brancher, J.D. BrasilEduca—An Open-Source MOOC platform for Portuguese speakers with gamification concepts. IEEE Front. Educ. Conf. 2014, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaibhav, A.; Gupta, P. Gamification of MOOCs for increasing user engagement. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on MOOCs, Innovation and Technology in Education (IEEE MITE 2014), Patiala, India, 19–20 December 2014; pp. 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, A.; Klemke, R.; Kreijns, K.; Specht, M. Get Gamification of MOOC right! How to Embed the Individual and Social Aspects of MOOCs in Gamification Design. Int. J. Serious Games 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, A.; Peter, D.; Klemke, R.; Bruysten, T.; Christian, M.; Specht, M. gMOOCs—Flow and Persuasion to Gamify MOOCs. In International Conference on Games and Learning Alliance; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS) Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10653, pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, A.; Klemke, R.; Stracke, C.M.; Specht, M. Identifying game elements suitable for MOOCs. In European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 355–360. [Google Scholar]

- Antonaci, A.; Klemke, R.; Stracke, C.M.; Specht, M. Towards Implementing Gamification in MOOCs. In International Conference on Games and Learning Alliance; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS) Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10653, pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.W.; Wei, H.Y. Exploring engaging gamification mechanics in massive online open courses. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2016, 19, 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Borras-Gene, O.; Martinez-Nuñez, M.; Fidalgo-Blanco, Á. New Challenges for the Motivation and Learning in Engineering Education Using Gamification in MOOC. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 32, 501–512. [Google Scholar]

- Binti Mohd Nor Hisham, F.; Sulaiman, S. Adapting Gamification Approach in Massive Open Online Courses to Improve User Engagement. In UTM Computing Proceedings Innovation in Computing Technology and Applications; UTM: Skudai, Malaysia, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Navío-Marco, J.; Solórzano-García, M. Student’s social e-reputation (“karma”) as motivational factor in MOOC learning. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernik, A.; Bubaš, G.; Radoševi, D. A Pilot Study of the Influence of Gamification on the Effectiveness of an e-Learning Course. In Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems; Faculty of Organization and Informatics Varazdin: Varazdin, Croatia, 2015; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Codish, D.; Ravid, G. Personality Based Gamification—Educational Gamification for Extroverts and Introverts. In CHAIS ’14—Conference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Technologies: Learning in the Technological Era; Eshet-Alkalai, Y., Caspi, A., Geri, N., Kalman, Y., Silber-Varod, V., Yair, Y., Eds.; The Open University of Israel: Raanana, Israel, 2014; pp. 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- De-Marcos, L.; Garciá-López, E.; Garciá-Cabot, A.; Medina-Merodio, J.A.; Domínguez, A.; Martínez-Herraíz, J.J.; Diez-Folledo, T. Social network analysis of a gamified e-learning course: Small-world phenomenon and network metrics as predictors of academic performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Marcos, L.; Domínguez, A.; Saenz-De-Navarrete, J.; Pagés, C. An empirical study comparing gamification and social networking on e-learning. Comput. Educ. 2014, 75, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Saenz-De-Navarrete, J.; De-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J.J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, D.; Vasalou, A.; Benton, L.; Khaled, R. Using Gamification to Motivate Students with Dyslexia. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’16), San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.; Betts, B. Encouraging user behaviour with achievements: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–19 May 2013; pp. 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, L.; Auvinen, T.; Korhonen, A. The effect of achievement badges on students’ behavior: An empirical study in a university- level computer science course. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2015, 10, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Hew, K.F. Do points, badges and leaderboard increase learning and activity: A quasi-experiment on the effects of gamification. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computers in Education, Hangzhou, China, 30 November–4 December 2015; Society for Computer in Education: Hangzhou, China, 2015; pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Hanus, M.D.; Fox, J. Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutas, A.; Ikonen, J.; Nikula, U.; Porras, J. Increasing collaborative communications in a programming course with gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies (CompSysTech ’14), Ruse, Bulgaria, 27–28 June 2014; Volume 883, pp. 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, M.; Mogalle, M.; Pohl, H.; Williams, J.J. A Playful Game Changer: Fostering Student Retention in Online Education with Social Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Learning@Scale (L@S’15), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, M.S.; Chuang, T.Y. How gamification motivates visits and engagement for online academic dissemination—An empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyewski, E.; Krämer, N.C. To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Comput. Educ. 2018, 118, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Aleven, V. Gamification of Joint Student / System Control over Problem Selection in a Linear Equation Tutor. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Trausan-Matu, S., Boyer, K.E., Crosby, M., Panourgia, K., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS) Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, L.Z.; Lopes, A.M.Z.; Prates, B.G.; Vassileva, J.; Isotani, S. Does gamification work for boys and girls? In Proceedings of the 30th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing—SAC ’15, Salamanca, Spain, 1–17 April 2015; ACM: Salamanca, Spain, 2015; pp. 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, M.R.U. LexiPal: Design, Implementation and Evaluation of Gamification on Learning Application for Dyslexia. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 131, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitra, O.; Katsigiannakis, V.; Karagiannidis, C.; Mavropoulou, S. The effect of badges on the engagement of students with special educational needs: A case study. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 3037–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, T.; Bittencourt, I.I.; Isotani, S.; Pedro, A.; Ospina, P. A gamified peer assessment model for online learning environments in a competitive context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, C.H.H.; Kofinas, A.; Luo, J. Enhancing student learning experience with technology-mediated gamification: An empirical study. Comput. Educ. 2018, 121, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, A.Y.; Santoso, H.B. Development of gamification-enriched pedagogical agent for e-Learning system based on community of inquiry. In Proceedings of the International HCI and UX Conference in Indonesia on (CHIuXiD ’15), Bandung, Indonesia, 8–10 April 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]