Exploring the Influence of Social Media Information on Interpersonal Trust in New Virtual Work Partners

Abstract

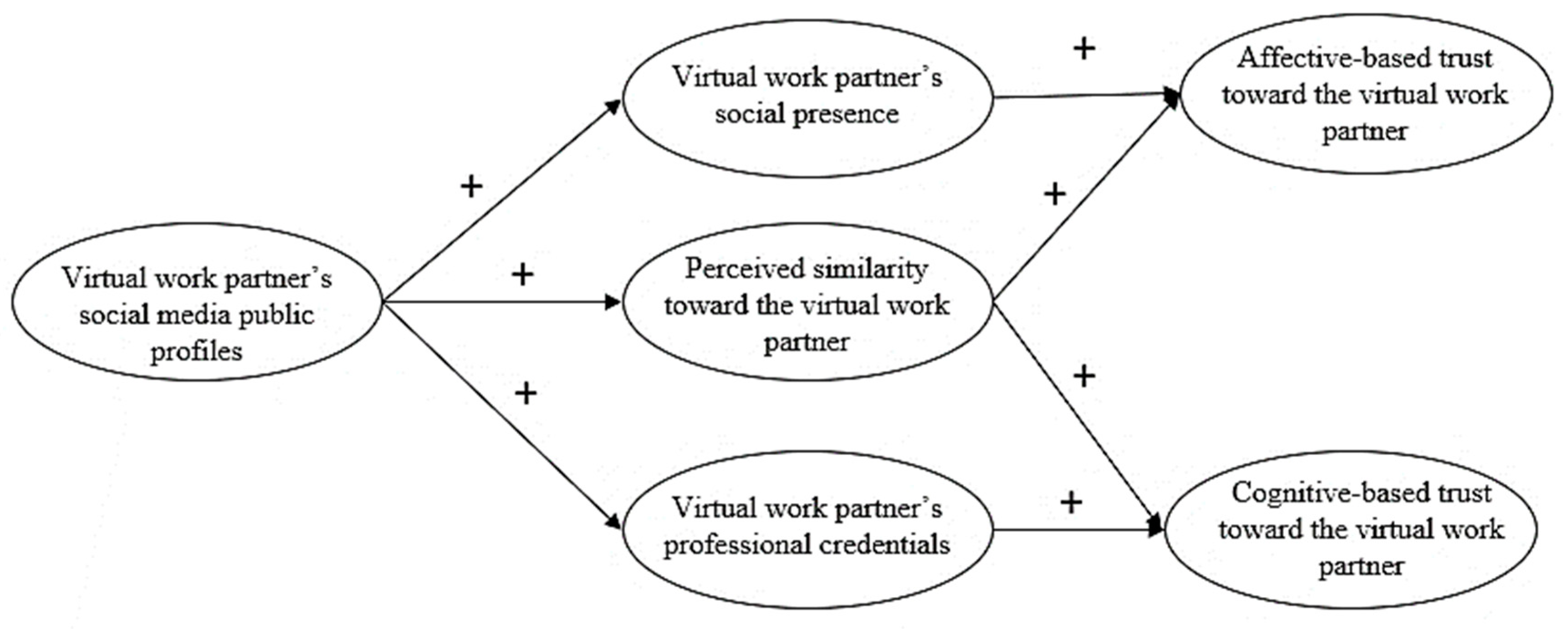

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Trust in New Virtual Work Partners

2.2. The Effect of Social Media Platforms

3. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baier, A.L. The ethical implications of social media: Issues and recommendations for clinical practice. Ethics Behav. 2019, 29, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiff, C. The Dark Triad and Facebook surveillance: How Machiavellianism, psychopathy, but not narcissism predict using Facebook to spy on others. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 94, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of Monthly Active Facebook Users Worldwide as of 2nd Quarter 2019. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ (accessed on 23 August 2019).

- Kuo, E.W.; Thompson, L.F. The influence of disposition and social ties on trust in new virtual teammates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 37, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Hoch, J.E. Virtual teams in organizations. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiller, C.; Van Der Heijden, B.; Chedotel, F.; Dumas, M. “You have a got a friend” The value of perceived proximity for teleworking success in dispersed teams. Team Perform. Manag. 2019, 25, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A. The factors behind working in virtual community. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2019, 12, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.C.; Hung, S. Examination of community identification and interpersonal trust on continuous use intention: Evidence from experienced online community members. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Knoll, K.; Leidner, D.E. Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1998, 14, 29–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanawattanachai, P.; Yoo, Y. Dynamic nature of trust in virtual teams. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bente, G.; Rüggenberg, S.; Krämer, N.C.; Eschenburg, F. Avatar-mediated networking: Increasing social presence and interpersonal trust in net-based collaborations. Hum. Commun. Res. 2008, 34, 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söllner, M.; Benbasat, I.; Gefen, D.; Leimeister, J.M.; Pavlou, P.A. Trust. MIS Quarterly Research Curations. Bush, A., Rai, A., Eds.; 2016. Available online: http://misq.org/research-curations (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Tsay-Vogel, M.; Shanahan, J.; Signorielli, N. Social media cultivating perceptions of privacy: A 5-year analysis of privacy attitudes and self-disclosure behaviors among Facebook users. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Vogel, D.; Guo, X.; Liu, H.; Gu, J. Understanding the influence of social media in the workplace: An integration of media synchronicity and social capital theories. In Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences (HCISS), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 3938–3947. [Google Scholar]

- Neeley, T.B.; Leonardi, P.M. Enacting knowledge strategy through social media: Passable trust and the paradox of nonwork interactions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 922–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, B. From virtual community members to C2C e-commerce buyers: Trust in virtual communities and its effect on consumers’ purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z. How do product recommendations affect impulsive buying? An empirical study on WeChat social commerce. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, S.Z.; Mandviwalla, M. Virtual Team Research: An analysis of theory use and a framework for theory appropriation. Small Group Res. 2007, 38, 12–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect- and cognition-based trust formations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D.; Weigert, A. Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoletti, P.; Resca, A.; Sæbø, Ø. Design for social media engagement: Insights from elderly care assistance. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, R.; Wakefield, K. Social media network behavior: A study of user passion and affect. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, M.R.; Littau, J. Interacting is believing: Interactivity, social cue, and perceptions of journalistic credibility on Twitter. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 2016, 93, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Van Der Heide, B. Evaluating the wisdom of strangers: The perceived credibility of online consumer reviews on yelp. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2014, 20, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. Job Market Signalling. Q. J. Econ. 1973, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D. Signaling Theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social Media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.A.; Williams, E.; Christie, B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, P. Social presence as a conduit to the social dimensions of online trust. In Persuasive Technology; IJsselsteijn, W., de Kort, Y., Midden, C., Eggen, B., van den Hoven, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Walther, J.B. Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction: A relational perspective. Commun. Res. 1992, 19, 52–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanis, M.; Postmes, T. A social identity approach to trust: Interpersonal perception, group membership and trusting behavior. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, R.; Lea, M. Social influence and the influence of the ‘social’ in computer-mediated communication. In Contexts of Computer-Mediated Communication; Lea, M., Ed.; Harvester Wheatsheaf: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1992; pp. 30–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. Understanding the trust building mechanisms in social media. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 70, 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.W.; Proudfoot, J.G.; Valacich, J.S. Saving face on Facebook: Privacy concerns, social benefits, and impression management. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Auckland, New Zealand, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinelli Watanuki, H.; de Oliveira Moraes, R. Exploring the Influence of Social Media Information on Interpersonal Trust in New Virtual Work Partners. Informatics 2019, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6030033

Martinelli Watanuki H, de Oliveira Moraes R. Exploring the Influence of Social Media Information on Interpersonal Trust in New Virtual Work Partners. Informatics. 2019; 6(3):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6030033

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinelli Watanuki, Hugo, and Renato de Oliveira Moraes. 2019. "Exploring the Influence of Social Media Information on Interpersonal Trust in New Virtual Work Partners" Informatics 6, no. 3: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6030033

APA StyleMartinelli Watanuki, H., & de Oliveira Moraes, R. (2019). Exploring the Influence of Social Media Information on Interpersonal Trust in New Virtual Work Partners. Informatics, 6(3), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics6030033