Scoping Review of Yoga in Schools: Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes in Both Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Youth Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Scope out the different mental health and cognitive functioning outcomes for neurotypical youth populations receiving a yoga intervention as part of the school day;

- Scope out the different mental health and cognitive functioning outcomes for neurodiverse youth populations receiving a yoga intervention as part of the school day;

- To explore the differences in the outcomes for neurotypical and neurodiverse youth populations.

2. Materials and Methods

- Stage 1: Identify the research question

- Stage 2: Identify relevant studies

Review Search Strategy

- Step 1: An initial search

- Step 2: Identify keywords and index terms

- Step 3: Searching electronic databases

- Step 4: Citation and reference lists

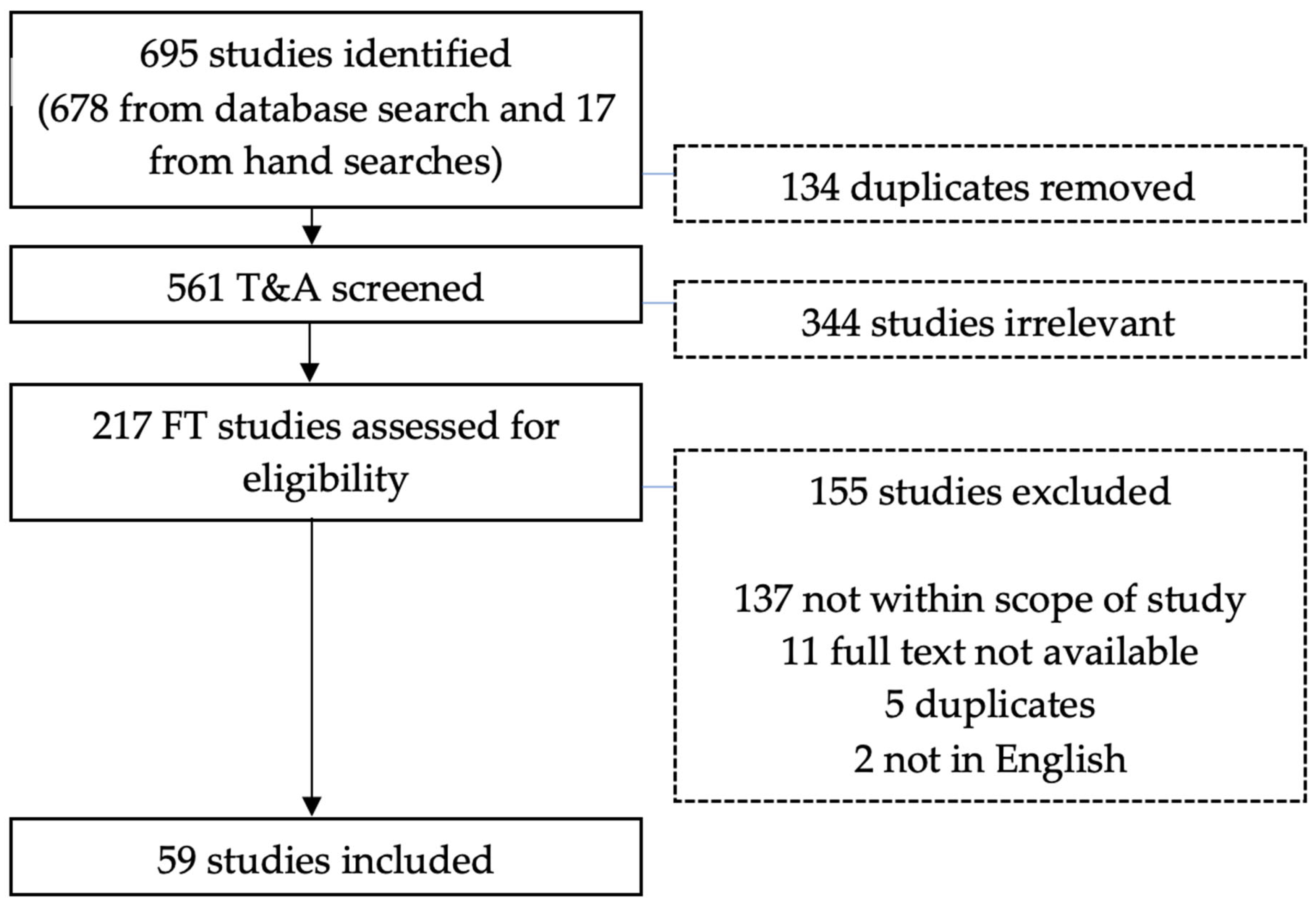

- Stage 3: Study selection

- (1)

- All identified studies were uploaded to Covidence software, where duplicates were automatically removed on upload.

- (2)

- Titles and abstracts were screened by N.H. with 100% double screened between the members of the research team. The entire research team (N.H., S.F., A.N. and J.B.) double screened 30% of the full-text review as a quality assurance measure. This increased confidence for one author (N.H.) to continue the subsequent 70% full-text review. If a paper could not be retrieved during the study selection process, the author(s) were contacted to request a copy. However, if the paper was not recovered, the study was excluded.

- Stage 4: Charting the data

- Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of All Studies

3.2. Neurodiverse Youth Populations

3.2.1. Neurodiverse Youth and Mental Health Outcomes

Self-Concept

Anxiety

Subjective Well-Being

3.2.2. Neurodiverse Youth and Cognitive Health Outcomes

Attention

Executive Function

Academic Performance

3.3. Neurotypical Youth

3.3.1. Neurotypical Youth and Mental Health Outcomes

Resilience

Self-Esteem

Self-Concept

Depression

Anxiety

Psychological and Subjective Well-being

3.3.2. Neurotypical Cognitive Outcomes

Inhibition

Attention

Working Memory

Executive Function

Academic Performance

Summary of Neurodiverse and Neurotypical Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Literature and Plausible Explanations for Findings

4.2. Mental Health Outcomes and Neurodiverse Populations

4.3. Mental Health Outcomes and Neurotypical Populations

4.4. Differences in the Mental Health Outcomes for Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Populations

4.5. Cognitive Outcomes and Neurodiverse Populations

4.6. Cognitive Outcomes and Neurotypical Populations

4.7. Differences in the Cognitive Outcomes for Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Populations

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

4.9. Future Research and Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Health Service. Delivering Effective Services for Children and Young People with ADHD; National Health Service: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rider, E.A.; Ansari, E.; Varrin, P.H.; Sparrow, J. Mental health and wellbeing of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ 2021, 374, n1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, C.; Read, J.; Spencer, N. Children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. In Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer: Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays; Chief Medical Officer (CMO): London, UK, 2012; Chapter 9; pp. 1–13. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/252659/33571_2901304_CMO_Chapter_9.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Simonoff, E.; Pickles, A.; Charman, T.; Chandler, S.; Loucas, T.; Baird, G. Psychiatric Disorders in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Associated Factors in a Population-Derived Sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 47, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parentzone. What Are Additional Support Needs? Available online: https://education.gov.scot/parentzone/additional-support/what-are-additional-support-needs/ (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Sayal, K.; Prasad, V.; Daley, D.; Ford, T.; Coghill, D. ADHD in children and young people: Prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman-Urrestarazu, A.; van Kessel, R.; Allison, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Brayne, C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Association of race/ethnicity and social disadvantage with autism prevalence in 7 million school children in England. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e210054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.E.; Henderson, M. Mental health promotion for young people-the case for yoga in schools. Educ. North 2018, 25, 139. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, S.S.; Stewart, V.; Wheeler, A.J.; Kelly, F.; Stapleton, H. Medication management in the context of mental illness: An exploratory study of young people living in Australia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Ciaccioni, S.; Thomas, G.; Vergeer, I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L.P.; Vanderloo, L.; Moore, S.; Faulkner, G. Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: An umbrella systematic review. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.B.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: Summary of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, S.S. Asana Pranayama Mudra Banda; Yoga Publications Trust: Munger, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Butzer, B.; Bury, D.; Telles, S.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Implementing yoga within the school curriculum: A scientific rationale for improving social-emotional learning and positive student outcomes. J. Child. Serv. 2016, 11, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Mendelson, T.; Lee-Winn, A.; Dyer, N.L.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials Testing the Effects of Yoga with Youth. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1336–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Vorkapic, C.; Feitoza, J.M.; Marchioro, M.; Simões, J.; Kozasa, E.; Telles, S. Are There Benefits from Teaching Yoga at Schools? A Systematic Review of Randomized Control Trials of Yoga-Based Interventions. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 345835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanthakumar, C. The benefits of yoga in children. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwacki, M.L.; Cook-Cottone, C. Yoga in the schools: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Yoga Ther. 2012, 22, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil-Sztramko, S.E.; Caldwell, H.; Dobbins, M. School-based physical activity programs for promoting physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 9, CD007651. [Google Scholar]

- Butzer, B.; Ebert, M.; Telles, S.; Khalsa, S.B.S. School-based yoga programs in the United States: A survey. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2015, 29, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.-C.; Huang, C.-J. Effects of an 8-week yoga program on sustained attention and discrimination function in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. PeerJ 2017, 5, e2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podgórska-Jachnik, D. Special and non-special. Dilemmas of the modern approach to the needs of people with disabilities. Interdiscip. Context Spec. Pedagog. 2018, 21, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Elwy, A.R.; Groessl, E.J.; Eisen, S.V.; Riley, K.E.; Maiya, M.; Lee, J.P.; Sarkin, A.; Park, C.L. A Systematic Scoping Review of Yoga Intervention Components and Study Quality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.; Richards, J.; Hillman, C.; Faulkner, G.; Beauchamp, M.; Nilsson, M.; Kelly, P.; Smith, J.; Raine, L.; Biddle, S. Physical Activity for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; Arlington, V.A., Ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Accept. Commit. Ther. Meas. Package 1965, 61, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson, R.J.; Hubner, J.J.; Stanton, G.C. Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Rev. Educ. Res. 1976, 46, 407–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, N.R.; Kiehl, E.M.; Lou Sole, M.; Byers, J. A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2006, 29, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, L.; Alliott, O.; Kelly, D.P.; Fawkner, D.S.; Booth, D.J.; Niven, D.A. The effect of physical activity interventions on executive functions in children with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 20, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, A.D.; Hitch, G. Working memory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1974; Volume 8, pp. 47–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm-Leary, K.; Borsato, G. Academic achievement. In Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 176–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.S.; Sze, S.L.; Siu, N.Y.; Lau, E.M.; Cheung, M.-C. A chinese mind-body exercise improves self-control of children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, N. Child and adolescent psychiatry. In Core Psychiatry E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: London, UK, 2012; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Kavale, K.A.; Spaulding, L.S.; Beam, A.P. A Time to Define: Making the Specific Learning Disability Definition Prescribe Specific Learning Disability. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2009, 32, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berwal, S.; Gahlawat, S. Effect of yoga on self-concept and emotional maturity of visually challenged students: An experimental study. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 39, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, J.T.; Hopkins, L.J. A study of yoga and concentration. Acad. Ther. 1979, 14, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatt, M.; Harpster, K.; Browne, E.; White, S.; Case-Smith, J. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes for Move-into-Learning: An arts-based mindfulness classroom intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 2013, 8, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Mehta, V.; Mehta, S.; Shah, D.; Motiwala, A.; Vardhan, J.; Mehta, N.; Mehta, D. Multimodal behavior program for ADHD incorporating yoga and implemented by high school volunteers: A pilot study. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 780745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Gilchrist, M.; Stapley, J. A journey of self-discovery: An intervention involving massage, yoga and relaxation for children with emotional and behavioural difficulties attending primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2008, 23, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Potter, L. Report on an Intervention Involving Massage and Yoga for Male Adolescents Attending a School for Disadvantaged Male Adolescents in the UK. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2010, 25, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.H.; Connington, A.; McQuillin, S.; Crowder Bierman, L. Applying the deployment focused treatment development model to school-based yoga for elementary school students: Steps one and two. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2014, 7, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, N.J.; Sidhu, T.K.; Pop, P.G.; Frenette, E.C.; Perrin, E.C. Yoga in an urban school for children with emotional and behavioral disorders: A feasibility study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uma, K.; Nagendra, H.R.; Nagarathna, R.; Vaidehi, S.; Seethalakshmi, R. The integrated approach of yoga: A therapeutic tool for mentally retarded children: A one-year controlled study. J. Ment. Defic. Res. 1989, 33 Pt 5, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Case-Smith, J.; Shupe Sines, J.; Klatt, M. Perceptions of children who participated in a school-based yoga program. J. Occup. Ther. Sch. Early Interv. 2010, 3, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxman, K. Socio-emotional well-being benefits of yoga for atypically developing children. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2022, 22, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.N.; Anderson, C.E.; Hylton, C.; Gustat, J. Effect of mindfulness and yoga on quality of life for elementary school students and teachers: Results of a randomized controlled school-based study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.K.; Agrawal, G. Yoga practice enhances the level of self-esteem in pre-adolescent school children. Int. J. Phys. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, K.A.; Madlem, M.S. Yoga, Physical Education, and Self-Esteem. Calif. J. Health Promot. 2007, 5, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Butzer, B.; Van Over, M.; Noggle Taylor, J.J.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Yoga may mitigate decreases in high school grades. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 259814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; Day, D.; Potts, A.; Ryan, C.; Coulombe, S.; Davies, B.; Weidknecht, K.; Ebert, M.; Flynn, L.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Effects of a Classroom-Based Yoga Intervention on Cortisol and Behavior in Second- and Third-Grade Students: A Pilot Study. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 20, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; LoRusso, A.; Shin, S.H.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Evaluation of Yoga for Preventing Adolescent Substance Use Risk Factors in a Middle School Setting: A Preliminary Group-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabre, P.C.; Pingale, P.V.; Tejrao, D.; Humbad, P.N. Effect of Suryanamskar, Pranayama and Yogasanas Training on the Intelligence of School Going Children. Int. J. Sports Sci. Fit. 2011, 1, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ehud, M.; An, B.-D.; Avshalom, S. Here and now: Yoga in Israeli schools. Int. J. Yoga 2010, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felver, J.C.; Butzer, B.; Olson, K.J.; Smith, I.M.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Yoga in Public School Improves Adolescent Mood and Affect. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 19, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felver, J.C.; Razza, R.; Morton, M.L.; Clawson, A.J.; Mannion, R.S. School-based yoga intervention increases adolescent resilience: A pilot trial. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2020, 32, 1698429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.L.; Bose, B.; Schrobenhauser-Clonan, A. Effectiveness of a School-Based Yoga Program on Adolescent Mental Health, Stress Coping Strategies, and Attitudes Toward Violence: Findings from a High-Risk Sample. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2014, 30, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.L.; Kohler, K.; Peal, A.; Bose, B. Effectiveness of a school-based yoga program on adolescent mental health and school performance: Findings from a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, L.F.; Dariotis, J.K.; Mendelson, T.; Greenberg, M.T. A school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth: Exploring moderators of intervention effects. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 40, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, K.; Sharma, S.K.; Telles, S.; Balkrishna, A. Self-esteem and performance in attentional tasks in school children after 4½ months of yoga. Int. J. Yoga 2019, 12, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Haden, S.C.; Daly, L.; Hagins, M. A randomised controlled trial comparing the impact of yoga and physical education on the emotional and behavioural functioning of middle school children. Focus Altern. Complement. Ther. 2014, 19, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagins, M.; Rundle, A. Yoga Improves Academic Performance in Urban High School Students Compared to Physical Education: A Randomized Controlled Trial: Yoga Improves Academic Performance in Urban High School Students. Mind Brain Educ. 2016, 10, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarraya, S.; Wagner, M.; Jarraya, M.; Engel, F.A. 12 weeks of Kindergarten-based yoga practice increases visual attention, visual-motor precision and decreases behavior of inattention and hyperactivity in 5-year-old children. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kale, D.; Kumari, S. Effect of 1-month yoga practice on positive-negative affect and attitude toward violence in schoolchildren: A randomized control study. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. Res. 2017, 3, 180. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, U.B.; Pramanik, T.N. Effect of Asanas and Pranayama on Self Concept of School Going Children. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 398–414. [Google Scholar]

- Manjunath, N.; Telles, S. Improved performance in the Tower of London test following yoga. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001, 45, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMahon, K.; Berger, M.; Khalsa, K.K.; Harden, E.; Khalsa, S.B.S. A Non-randomized Trial of Kundalini Yoga for Emotion Regulation within an after-school Program for Adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noggle, J.J.; Steiner, N.J.; Minami, T.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012, 33, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, S.A.; Satish, L. When does yoga work? Long term and short term effects of yoga intervention among pre-adolescent children. Psychol. Stud. 2014, 59, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, G.; Shete, B.T.K.; Uddhav, S.S. Yoga for Controlling Examination Anxiety, Depression and Academic Stress among Students Appearing for Indian Board Examination. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2013, 4, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Quach, D.; Mano, K.E.J.; Alexander, K. A randomized controlled trial examining the effect of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, S.; Razza, R. Exploring the Efficacy of a School-based Mindful Yoga Program on Socioemotional Awareness and Response to Stress among Elementary School Students. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2022, 31, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Tietjens, M.; Ziereis, S.; Querfurth, S.; Jansen, P. Yoga training in junior primary school-aged children has an impact on physical self-perceptions and problem-related behavior. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, K.; Verrico, C.D.; Saxena, J.; Kurian, S.; Alexander, S.; Kahlon, R.S.; Arvind, R.P.; Goldberg, A.; DeVito, N.; Baig, M.; et al. An Evaluation of Yoga and Meditation to Improve Attention, Hyperactivity, and Stress in High-School Students. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2020, 26, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreve, M.; Scott, A.; McNeill, C.; Washburn, L. Using yoga to reduce anxiety in children: Exploring school-based yoga among rural third-and fourth-grade students. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2021, 35, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, A.; Kumari, S.; Ganguly, M. Development, validation, and feasibility of a school-based short duration integrated classroom yoga module: A pilot study design. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Stueck, M.; Gloeckner, N. Yoga for children in the mirror of the science: Working spectrum and practice fields of the training of relaxation with elements of yoga for children. Early Child Dev. Care 2005, 175, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, S.; Singh, N.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Balkrishna, A. Effect of yoga or physical exercise on physical, cognitive and emotional measures in children: A randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2013, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paleville, D.G.T.; Immekus, J.C. A Randomized Study on the Effects of Minds in Motion and Yoga on Motor Proficiency and Academic Skills among Elementary School Children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, A.M.; López, M.A.; Quiñonez, N.; Paba, D.P. Yoga for the prevention of depression, anxiety, and aggression and the promotion of socio-emotional competencies in school-aged children. Educ. Res. Eval. 2015, 21, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shete, S.U. Effect of yoga practices on general mental ability in urban residential school children. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2020, 17, 20190238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shete, S.; Thakur, G.S. The effect of yoga practices on cognitive development in rural residential school children in India. Memory 2014, 6, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vhavle, S.P.; Rao, R.M.; Manjunath, N. Comparison of yoga versus physical exercise on executive function, attention, and working memory in adolescent schoolchildren: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Yoga 2019, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berezowski, K.A.; Gilham, C.M.; Robinson, D.B. A Mindfulness Curriculum: High School Students’ Experiences of Yoga in a Nova Scotia School. Learn. Landsc. 2017, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B.; LoRusso, A.M.; Windsor, R.; Riley, F.; Frame, K.; Khalsa, S.B.S.; Conboy, L. A qualitative examination of yoga for middle school adolescents. Adv. Sch. Ment. Health Promot. 2017, 10, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conboy, L.A.; Noggle, J.J.; Frey, J.L.; Kudesia, R.S.; Khalsa, S.B.S. Qualitative evaluation of a high school yoga program: Feasibility and perceived benefits. Explore 2013, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxman, K. Exploring the Impact of a Locally Developed Yoga Program on the Well-Being of New Zealand School-Children and Their Learning. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2021, 27, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rashedi, R.N.; Wajanakunakorn, M.; Hu, C.J. Young children’s embodied experiences: A classroom-based yoga intervention. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 3392–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindl, D.; Hamm, A.; Lewis, R.; Gellar, L. Elementary student and teacher perceptions of a mindfulness and yoga-based program in school: A qualitative evaluation. Explore 2020, 16, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hagins, M. Perceived Benefits of Yoga among Urban School Students: A Qualitative Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 8725654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, T.; Greenberg, M.T.; Dariotis, J.K.; Gould, L.F.; Rhoades, B.L.; Leaf, P.J. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkissian, M.; Trent, N.L.; Huchting, K.; Singh Khalsa, S.B. Effects of a Kundalini Yoga Program on Elementary and Middle School Students’ Stress, Affect, and Resilience. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2018, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivashankar, J.T.; Surenthirakumaran, R.; Doherty, S.; Sathiakumar, N. Implementation of a non-randomized controlled trial of yoga-based intervention to reduce behavioural issues in early adolescent school-going children in Sri Lanka. Glob. Health 2022, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.M.; Centeio, E.E. The benefits of yoga in the classroom: A mixed-methods approach to the effects of poses and breathing and relaxation techniques. Int. J. Yoga 2020, 13, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I.; Lipowska, M. Physical activity and cognitive functioning of children: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P. Assessment and development of executive function (EF) during childhood. Child Neuropsychol. 2002, 8, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, D.; Knoll, L.J.; Blakemore, S.-J. Adolescence as a sensitive period of brain development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 19, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, N.; Fawkner, S.; Niven, A.; Booth, J.N. Scoping review on Yoga in Schools. 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/6p8av/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

| Terminology | Definition Used |

|---|---|

| Yoga in Schools | Yoga interventions either before, during or after school. Studies that utilise at least two of the four main components of yoga: physical postures [27] and movement, breathwork, relaxation techniques and meditation/mindfulness practices [15]. |

| Neurotypical | Those who are developing like others of the same age and are not receiving additional or different support. |

| Neurodiverse | Those who require additional support that is different from that received by children of the same age to ensure they benefit from education, whether early learning, school or preparation for life after school [6]. |

| Terminology | Definition Used |

|---|---|

| Mental Health Outcomes | Adapted from Biddle, Ciaccioni, Thomas and Vergeer [11] and Lubans et al. [28]. |

| Anxiety | Activation of the automatic nervous system with distressing thoughts and/or feelings of tension, agitation, excessive worry or apprehension about certain events (such as environment, social, academic, occupational) [29]. |

| Depression | Extended periods of low mood and loss of interest or pleasure in generally all activities [29]. |

| Self-esteem | An individual’s evaluation of their own worth [30]. |

| Self-concept | An individual’s awareness or beliefs regarding their qualities and limitations both globally and in specific subdomains (e.g., academic, physical, social) [31]. |

| Psychological Well-being | Psychological well-being links with autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life and self-acceptance. This is often referred to as eudemonic well-being [29]. |

| Subjective-Well-being | Subjective well-being is defined as a person’s cognitive and affective evaluations of their life. SWB is closely aligned with the construct of happiness [32]. |

| Resilience | A personality characteristic that moderates the negative effects of stress and enables individuals to successfully cope with challenges and misfortune [33]. |

| Cognitive Outcomes | Adapted from Diamond [34] and Welsch, Alliott, Kelly, Fawkner, Booth, Niven [35]. |

| Executive Function | The cognitive processes that are used to carry out new or difficult tasks. These processes include inhibition, working memory, shifting and attention [34]. |

| Inhibition | The control of attention, behaviour, thoughts and emotions by overriding internal tendencies or external distractions [34]. |

| Working Memory | The of holding information in the mind and working with it mentally [36], e.g., thinking of a response while listening to a conversation. |

| Shifting | The flexibility to adjust to changed demands or priorities [34]. |

| Attention | The ability to focus on information for several seconds (interrelated with working memory) [34]. |

| Academic Performance | Academic performance broadly refers to the communicative (oral, reading, writing), mathematical, science, social science and thinking skills and competencies that enable a child to succeed in school and society. Because these forms of achievement are difficult to assess, most researchers have relied on a narrower definition that is largely limited to outcomes on standardised achievement tests [37]. |

| IQ | Intelligence quotient [38] refers to mental age (MA) expressed as a ratio of chronological age (CA) multiplied by 100. For IQ to remain stable, MA must increase with CA over time [39]. |

| Neurodevelopmental Impairments | The American Psychiatric Association [29] define neurodevelopmental disorders that present themselves at the onset of the developmental stage through personal, social, academic and occupational impairments. |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is defined by the American Psychiatric Association [29] as a consistent pattern of inattention, impulsivity and/or hyperactivity. |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder [38] is a complex developmental disorder that involves persistent challenges in social interaction, restricted and repetitive behaviours and speech and non-verbal communication [29]. The severity and effects of ASD differ between each individual. |

| Learning Difficulties | Identified as a particular type of “unexpected” low achievement and distinguished from types where low achievement is expected due to emotional disturbance, social or cultural disadvantage or inadequate instruction [40]. |

| Author & Year | Methods | Control Group (CG) | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes | Effects Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berwal and Gahlawat, 2013 [42] | Pre-post | NO | n = 15 14–18 years No gender details Visually impaired students drawn from a special school for the blind in India. | Ashtanga and theory yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation and theory classes on the importance of yoga 30 days daily for 60 min. | Self-concept | Improvement in all dimensions of self-concept, including academic, intellectual and social. |

| Case-Smith, Shupe Sines and Klatt, 2010 [51] | Qualitative | NO | n = 21 7.4 years (mean) F = 12/M = 9 3 participants received additional support for learning. | Hatha yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation + 15 min activities at end for self-concept (e.g., making an Olympic medal to wear or a collage of people who loved them) 45 min × 1 a week for 8 weeks. In addition, 4 days a week, the teacher of the class led 15 min yoga in the classroom. | Self-concept, attention | Three themes emerged:

|

| Hopkins and Hopkins, 1979 [43] | Within-groups | YES—general PE activities | n = 34 6–11 years No gender details Not labelled but exhibit severe educational problems | Yoga—Postures, breathing and meditation 2 conditions—15 min for 8 or 22 sessions (duration not detailed) | Attention | Both treatments were followed by more efficient completion of the criterion task than CG. |

| Klatt, Harpster, Browne, White and Case-Smith, 2013 [44] | Mixed methods | NO | n = 41 8.54 years (mean + 0.55) F = 25/M = 16 The teachers describe some of the participants as having ADHD symptoms. | Mindfulness-based Intervention (MIL)—Postures, meditation, background music, art activities with weekly overarching theme, e.g., health, support, success 45 min × 1 a week for a total of 8 weeks conducted during the school day in the classroom | Attention | Assessment of student behaviour on both ADHD index and in cognitive/inattentive behaviour showed decreases in disruptive behaviours. |

| Laxman, 2022 [52] | Qualitative | NO | n = 3 15–18 years Participants were conveniently recruited as they had learning and intellectual disabilities and varying degrees of autism. | Goldberg’s Creative Relaxation Programme designed for young people with autism—postures, breathing and relaxation 15 min × 1 week for 5 weeks in the classroom | Subjective well-being | Improvements in positive affect were noted by some students. |

| Mehta, Mehta, Mehta, Shah, Motiwala, Vardhan, … and Mehta, 2011 [45] | Pre-post | NO | n = 63 6–11 years F = 26/M = 44 Participants were recruited as they had been diagnosed previously with ADHD using the Vanderbilt questionnaire as well as having a neurodevelopmental assessment by a neurodevelopmental paediatrician. | Multimodal programme that incorporates yoga as well as behavioural play therapy—Postures, breathing and meditation, behavioural play 60 min × 2 a week over 6 weeks during the school day | Academic performance | More than 50% of the children improved their academic and behavioural performance. |

| Powell and Potter, 2010 [47] | Pre-post | NO | n = 21 11–15 years M = 21 Of the 21 pupils, 6 were diagnosed with an EBD alone, 2 were diagnosed with EBD and ADHD, 1 was diagnosed with ADHD alone, 1 was reported by teachers to have ADHD and epilepsy, and 1 child had a diagnosis of global delay. The remaining 9 pupils had mild to severe learning disabilities. Six pupils were in receipt of additional help. | Hatha yoga and self/peer massage—Postures, massage, breathing, meditation, relaxation and visualisation 60 min × 12 classes over 2 school terms in a room in the school | Attention | Positive change was noted by teachers of pupils’ reduced hyperactivity. No statistically significant changes, but there were trends toward improvements in attention span and eye contact with teachers. |

| Powell, Gilchrist and Stapley, 2008 [46] | Quasi-experimental | YES—regular additional support as normal | n = 107 8–11 years F = 48/M = 59 Participants exhibited emotional, behavioural and learning difficulties. | Self-Discovery Programme—Postures, breathing, relaxation, communication and massage 45 min × 1 a week over 12 weeks | Attention | The yoga group had significant improvements in ‘contribution in the classroom’; however, there were greater trends towards improvement in attention in CG. |

| Smith, Connington, McQuillin and Crowder Bierman, 2014 [48] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—CG attended Healthy Eats: a non-physical activity | n = 77 9.38 years (+0.97) F = 41/M = 36 16 of the 77 students were categorised as ‘special education’. | ‘YogaKidz’ Curriculum—Postures, breathing, relaxation and didactic themes 40 min × 2 a week for 28 weeks | Academic performance | Better growth in reading scores for the yoga group as opposed to decline in scores for CG. |

| Steiner, Sidhu, Pop, Frenette and Perrin, 2013 [49] | Pre-post | NO | n = 37 8–11 years (10.4 mean age) F = 15/M = 22 9.8% had attention problems (ADHD), 9.8% depression/bi-polar, 19.5% anxiety/OCD, 24.4% behaviour problems, 24.4% autism spectrum disorder, 7.3% neurological problems and 58.5% school problems including speech and language, reading. | ‘Yoga Ed’ Protocol—Postures, breathing, relaxation, social component of partner/group exercises, imagery and meditation 60 min × 2 a week for 3.5 months during school hours | Anxiety, attention, psychological and subjective well-being, executive function. | Teachers reported improved attention in class, adaptive skills and reduced depressive symptoms. Children did report increased anxiety. |

| Uma, Nagendra, Nagarathna, Vaidehi and Seethalakshmi, 1989 [50] | Quasi-experimental | YES—no treatment | n = 90 6–16 years F = 32/M = 58 Students were selected based on mild, moderate and severe functional impairment such as IQ and adaptive skills. Amongst those who were included in the study, 12 pairs (pairs refer to control and treatment balanced) belonged to the mild degree (IQ 50–70), 17 pairs belonged to the moderate degree (IQ 35–50), and 16 pairs belonged to the severe degree (IQ 20–34). | Yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation 60 min × 5 days a week for 10 months | IQ | IQ scores improved significantly in the yoga group compared to the CG. |

| Author & Year | Methods | Control Group (CG) | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes | Effects Found |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazzano, Anderson, Hylton and Gustat, 2018 [53] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—’care-as-usual’ (CG) | n = 52 8–9 years Positive for symptoms of anxiety using the SCARED scale F = 25/M = 27 Typically developing. | ‘Yoga Ed’—Postures, breathing and meditation 40 min × 10 sessions for 8 weeks held in a classroom in the mornings | Subjective well-being | The yoga group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in psychosocial and emotional quality of life compared with CG. |

| Berezowski, Gilham and Robinson, 2017 [90] | Qualitative | NO | n = 3 16–18 years No gender details | ‘Yoga 11 curriculum’—Postures, breathing, meditation, philosophy and life skills Participants completed the Yoga 11 course as part of their Physical Education. Duration unknown. | Subjective well-being | Participants generally expressed how yoga made them feel happier (affect). |

| Bhardwaj and Agrawal, 2013 [54] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—no treatment but free to complete homework or reading | n = 44 10–12 years (mean 11.27) F = 18/M = 26 | Yoga—Postures, breathing and relaxation and OM chanting 35 min × 6 days a week for one month during school time | Self-esteem | The yoga group demonstrated a significant rise in the level of total self-esteem, general self-esteem and social self-esteem compared to CG. No significant changes found in the academic or parental self-esteem outcomes. |

| Bridges and Madlem, 2007 [55] | Quasi-experimental | YES—traditional PE | n = 53 13–14 years F = 24/M = 29 | Yoga—no info 40 min × 2 a week for 16 weeks | Self-esteem | Self-esteem increased in both the experimental and CG with no significant differences between the two groups. |

| Butzer, Van Over, Noggle Taylor and Khalsa, 2015 [56] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 95 14–17 years F = 55/M = 40 | ‘Kripalu Yoga’—Postures, breathing, game/activity and meditation and relaxation 35–40 min × 2/3 times a week for 12 weeks | Academic performance | Both groups exhibited a decline in GPA over the school year. However, CG exhibited a significantly greater decline in GPA over time than the yoga group. |

| Butzer, Day, Potts, Ryan, Coulombe, Davies,… and Khalsa, 2015 [57] | Pre-post | NO | n = 36 6–8 years F = 16/M = 30 | ‘Yoga 4 Classrooms’ programme—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation + themed discussion at start class to promote self-inquiry and reflection. 30 min weekly class over 10 weeks. Taught during regular class time | Attention and academic performance | Teacher reported significant improvements in attention span, ability to concentrate on work, ability to stay on task and academic performance. |

| Butzer, LoRusso, Windsor, Riley, Frame, Khalsa and Conboy, 2017 [91] | Qualitative | YES—traditional PE | n = 16, 13.27 years (+0.42) F = 8/M = 8 | Kripalu Yoga in the Schools (KYIS)—Postures, breathing, didactic/experiential content and relaxation 35 min × 1 or 2 a week for 6 months | Academic performance | Participants mentioned using breathing techniques to help prepare for tests, while other students mentioned improvements in academic performance, with 25% showing improvements through Valence analysis. |

| Butzer, LoRusso, Shin and Khalsa, 2017 [58] | Randomised controlled trial | YES- traditional PE | n = 209 12.64 years (+0.33) F = 132/M = 77 | Kripalu Yoga in the Schools (KYIS)—Postures, breathing, didactic/experiential content and relaxation 35 min × 1 or 2 a week for 6 months | Depression and inhibition | The entire sample (yoga and CG) reported significant increases in depression. |

| Conboy, Noggle, Frey, Kudesia and Khalsa, 2013 [92] | Qualitative | NO | n = 28 15 years F = 17/M = 11 | Kripalu Yoga (KYIS)/classical Hatha yoga style—Postures, breathing exercises, deep relaxation and meditation techniques 30 min for 12 weeks | Attention and academic performance | Little direct effect on grades. Participants noted that yoga helped to relieve academic stress and improve attitudes towards school. Students used the breathing techniques taught in the yoga classes to prepare for exams. Other students noted that yoga during the day improved their ability to focus and concentrate. |

| Dabre, Pingale, Tejrao and Humbad, 2011 [59] | Quasi-experimental | YES—other school activities | n = 154 11–13 years No gender details | Yoga—Postures, breathing and meditation Once a day as part of school’s morning routine, 6 days a week for 10 months | Academic performance | There was a rise in the school results of yoga group, whereas no difference between the CG and school results. |

| Ehud, An and Avshalom, 2010 [60] | Pre-post | NO | n = 122 8–12 years No gender details | Iyengar- Postures and breathing 13 yoga sessions conducted over 4 months incorporated into school schedule | Attention | There was a significant improvement of attention. |

| Felver, Butzer, Olson, Smith and Khalsa, 2014 [61] | Within-groups | YES—traditional PE | n = 47 14–16 years F = 52%/M = 48% | Kripalu Yoga in Schools (KYIS)—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation 35 min × 5 days for 3 weeks | Subjective well-being | Immediate improvements in mood and affect were noted following both yoga and CG; however, the yoga class had a larger effect than traditional PE. |

| Felver, Razza, Morton, Clawson and Mannion, 2020 [62] | Quasi-experimental | YES—art or music class | n = 23 12.1 years F = 12/M = 11 | Kripalu Yoga in Schools (KYIS) + Normal PE programming—Postures, breathing, relaxation and didactic theme 45 min × 7 days a week over 7 weeks (n = 33) | Resilience | Participants in the yoga group demonstrated significant improvements in resilience over time, whereas scores in the CG did not significantly change. |

| Frank, Bose and Schrobenhauser-Clonan, 2014 [63] | Quasi-experimental | NO | n = 49 14–18 years F = 27/M = 22 | TLS (Transformative Life Skills)-A manualised universal classroom-based programme—Postures, breathing and meditation. Sessions integrated into the classroom 30 min × 3–4 days per week during the first semester of the school year. | Subjective well-being, anxiety, depression | No statistically significant differences in measures of positive affect and negative affect were found. However, the general direction of scores was in predicted direction. Significant improvements were found in measures of student anxiety and depression. |

| Frank, Kohler, Peal and Bose, 2017 [64] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—’business as usual’ | n = 159 11–15 years F = 74/M = 81 | TLS (Transformative Life Skills)-A manualised classroom-based programme—Postures, breathing and meditation. Sessions integrated into the classroom 30 min × 3–4 days per week during the first semester of the school year. | Academic performance, subjective well-being | No differences between groups were noted on measures of positive, negative affect or grades. However, as compared to the CG, students in the yoga intervention had improved levels of school engagement. |

| Gould, Dariotis, Mendelson and Greenberg, 2012 [65] | Quasi-experimental | YES—waitlist | n = 97 9–11 years F = 59/38 | Holistic Life Foundation (HLF)—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation 45 min × 4 days a week for 12 weeks. Classes were held in the school’s physical activity rooms, e.g., hall or gym, during ‘resource time’—a period in which students engage in non-academic activities | Depression, inhibition | Baseline depressive symptoms moderated both impulsive action and involuntary engagement stress responses. The yoga group reporting lower levels of baseline depressive symptoms were more likely to report decreases in impulsive action and involuntary engagement responses relative to CG. |

| Gulati, Sharma, Telles and Balkrishna, 2019 [66] | Pre-post | NO | n = 116 10.2 (+0.6) years F = 38/M = 78 | Yoga—Postures, breathing, relaxation and chanting 60 min daily × 7 days a week | Self-esteem, attention | Improvements in attention, concentration and self-esteem (social, academic, and total) were found. |

| Haden, Daly and Hagins, 2014 [67] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 30 10–11 years F = 13/M = 17 | Ashtanga—Postures, breathing, relaxation and meditation 1.5 h × 3 times a week for 12 weeks | Subjective well-being and psychological well-being | No significant differences between groups. Negative affect increased in yoga group and decreased in CG, as well as a non-significant increase in positive affect in the yoga group. |

| Hagins and Rundle, 2016 [68] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 112 14–17 years F = 54/M = 58 | ‘Sonima Foundation Yoga curriculum’—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation and discussion on didactic themes 45 min × 2 a week over the academic year (n = 58 classes) | Academic performance, executive function, well-being | Yoga group participants had a higher mean GPA than CG. No changes to executive function were found. There was a trend of poorer well-being scores in the yoga group. |

| Jarraya, Wagner, Jarraya and Engel, 2019 [69] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—PE (active CG) OR no treatment | n = 45 5.2 years (+0.4) F = 28/M = 17 | Hatha Yoga—Jogging/jumping warm-up, breathing, yoga postures, sensory games and story 30 min × 2 a week over 12 weeks (total n = 24) during normal kindergarten hours | Attention | The yoga group, in comparison to both CGs, had a significant positive impact on inattention and hyperactivity. |

| Kale and Kumari, 2017 [70] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—no details | n = 60 12–15 years M = 60 | Yoga—Prayer, postures, breathing, mantra chanting, cleansing processes and relaxation OR CG (no details) 60 min × 6 days a week in school afternoon | Subjective well-being | There was a significant positive improvement in positive affect and a significant reduction in negative affect in the yoga group. |

| Kundu and Pramanik, 2014 [71] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—Group D had no treatment | n = 120 8–10 years M = 120 | Group A—postures only OR Group B—breathing only OR Group C—postures and breathing 45 min × 6 days a week for 12 weeks in the school activity hall | Self-concept, subjective well-being, anxiety | Anxiety was significantly improved in all groups but showed better effects in Group C. Happiness and satisfaction were significantly improved in all groups. Self-concept was significantly improved in all groups. |

| Laxman, 2021 [93] | Qualitative | NO | n = 6 9–14 years No gender details | Yoga—Postures, breathing and meditation and relaxation 1 × a week for 60 min in school hall building for 5 weeks (total n = 6) | Attention, subjective well-being | A general increase in subjective well-being during and after the yoga sessions was found. Participants also reported improved attention. |

| Manjunath and Telles, 2001 [72] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 20 10–13 years F = 20 | Yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation, relaxation and singing devotional songs 75 min × 7 days a week in residential school for one month | Executive function | Yoga significantly improved execution time and planning time. Planning time was also improved in the CG. |

| McMahon, Berger, Khalsa, Harden and Khalsa, 2021 [73] | Quasi-experimental | YES—homework/outdoor play | n = 118 11–14 years F = 63/Male = 55 | Kundalini Yoga-based Y.O.G.A for Youth (Y4Y)—Postures, breathing, meditation, relaxation, singing and mantras. Yogic principles such as intention, action, speech etc. were taught through group discussion 2 × 40 min classes a week over 6 weeks | Depression, anxiety | Participants in the yoga group reported significant decreases in depression after one session. Yoga’s impact on depression and anxiety depended on the school setting in which they were implemented. |

| Mendelson, Greenberg, Dariotis, Gould, Rhoades and Leaf, 2010 [97] | Mixed methods | YES—waitlist | n = 97 9–11 years F = 59/M = 38 | Holistic Life Foundation (HLF) mindfulness-based yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation, relaxation and didactic discussions based on stressors and coping mechanisms 45 min × 4 days a week for 12 weeks in a gym hall during school hours | Inhibition, subjective well-being, depression | No significant group differences on measures of mood or depressive symptoms were found, although the pattern of scores was in predicted direction for mood variables. Significant differences were found in two of the five subscales of involuntary stress responses post-intervention means, including rumination and intrusive thoughts and a trend in predicted direction for impulsive action. |

| Noggle, Steiner, Minami and Khalsa, 2012 [74] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 51 16–18 years F = 28/M = 23 | Kripalu-based yoga programme—Postures, breathing, meditation and didactic discussion on self-inquiry and emotion regulation 30 min × 2 or 3 a week over 10 weeks (n = 28 total) | Subjective well-being, psychological well-being, depression, anxiety, resilience | Negative affect and tension–anxiety were all positively impacted by the intervention. However, no changes were observed in positive affect or, perceived stress, positive psychological traits, resilience., or anger expression. |

| Pandit and Satish, 2014 [75] | Longitudinal | YES—three conditions including yoga, non-yoga intervention and a time-lagged comparison group | n = 178 9–12 years No gender details | Yoga—Postures, breathing and chanting Every other week for 12 weeks/daily practice at home | Attention and executive function | Significant changes in the attention scores in all three groups over three to six months were found. Results also showed improvement in problem-solving scores across time in all three groups over three to six months. |

| Pant, 2013 [76] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—school as usual | n = 60 16–17 years M = 60 | Yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation, relaxation and chanting 60 min × daily for 6 weeks | Anxiety and depression | Reduction of examination anxiety, depression and academic stress was found in the yoga group. |

| Quach, Mano and Alexander, 2016 [77] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—mindfulness meditation OR PE waitlist | n = 198 (only 172 accounted for in gender) 12–15 years (13.18) F = 114/M = 58 | Hatha yoga—Postures, breathing, discussion 45 min × 2 × weekly for 4 weeks during PE time in either gym or hall Participants asked to complete 15–30 min daily home practice, which was logged in a diary collected once a week | Working memory, anxiety | A significant increase in working memory was found for participants in meditation group, whereas those in yoga and CG did not present significant changes. All three groups showed significantly reduced anxiety post-intervention. |

| Rashedi, Wajanakunakorn and Hu, 2019 [94] | Qualitative | Part of an ongoing RCT with waitlist control | n = 154 4–6 years No gender details | Yoga on pre-recorded videos—Postures, breathing, relaxation and songs 10 min × 6 weekly before lunch for 8 weeks | Subjective well-being, attention | Attention and subjective well-being improved following the yoga programme. |

| Reindl, Hamm, Lewis and Gellar, 2020 [95] | Qualitative | NO | n = 40 students/23 teachers 8–11 years No gender details | No intervention details 1-year intervention | Attention, academic performance, self-esteem | Students perceived improved focus and academic performance whilst teachers reported increased cognitive functioning and self-esteem. |

| Reid and Razza, 2022 [78] | Quasi-experimental | YES—traditional PE as normal | n = 112 10–12 years (mean age= 10.4 years) F = 58/M = 54 | Mindfulness through Movement (MTM)—postures, breathing, relaxation and mindfulness 45 min 2 × a week for 7 months | Inhibition | Participants in the YG reported lower levels of rumination and intrusive thoughts than their peers in the CG. |

| Richter, Tietjens, Ziereis, Querfurth and Jansen, 2016 [79] | Quasi-experimental | YES—physical skill training | n = 24 6–11 years F = 12/M = 12 | Yoga embedded into story—Postures connected by story, e.g., imagining a moon and doing ‘moon pose’ 45 min × 2 a week for 6 weeks. Classes were conducted in afternoon and outside of regular sports lessons and took place in a suitable room within the school. | Executive function, self-concept | No differences between groups were found in executive function and motor skills. Participants in the yoga group reported an increase in the category speed of physical self-concept compared to CG. |

| Sarkissian, Trent, Huchting and Khalsa 2018 [98] | Mixed methods | NO | n = 30 9–14 years F = 25/M = 5 | Kundalini Yoga (Your Own Greatness Affirmed; YOGA)—Postures, breathing, meditation 50 min × 1/2 times a week for 10 weeks within the schools’ regular PE time slot or after school | Subjective well-being, resilience, academic performance | Improved positive affect and resilience were found. However, a non-significant increase in negative affect was also reported. |

| Saxena, Verrico, Saxena, Kurian, Alexander, Kahlon…and Gillan, 2020 [80] | Quasi-experimental | YES—health class | n = 174 14–15 years F = 112/M = 62 | Hatha Yoga—Postures and meditation OR health class (CG) 25 min × 2 a week for 12 weeks. Classes took place in the morning during a required health class | Attention | Compared to CG, the yoga group reduced inattention and hyperactivity. Within the yoga group, inattention and hyperactivity symptoms diminished. |

| Shreve, Scott, McNeill and Washburn, 2021 [81] | Quasi-experimental | YES—those who did not participate were the CG | n = 71 8–10 years F = 42/M29 | Adapted 10 min version of ‘Yoga for Kids’ programme to be used in schools—Postures, breathing, relaxation and meditation 10 min × 5 days a week for 8 weeks. Yoga was completed first thing in the morning before teaching | Anxiety and academic performance | 63% of the yoga group presented with elevated anxiety scores at baseline and reduced to 40% post-intervention. On average, participants in the yoga group had significantly improved academics post-intervention. |

| Sinha, Kumari and Ganguly 2021 [82] | Pre-post | NO | n = 49 12–16 years (mean 13.6 years) F = 26/M = 23 | An integrated classroom yoga module (ICYM)—Postures, breathing, chanting, affirmations and meditation 12 min × 5 days a week for 1 month | Self-esteem, well-being and executive function | Significant improvements post-intervention for executive function were found with medium–large effect sizes. Significant improvements in self-esteem were found post-intervention with a small effect size. No significant differences were found post-intervention for well-being. |

| Sivashankar, Surenthirakumaran, Doherty and Sathiakumar, 2022 [99] | Mixed methods | YES—normal ‘keep fit’ routine of dancing for 20 min | n = 1084 13–14 years F = 549/M = 535 | Yoga—Postures, breathing and meditation 20 min × 4 days a week for 6 months | Academic performance | Students noted an increase in their academic performance as a benefit of the yoga programme, with one student explaining, “I can quickly complete my homework easily”. |

| Stueck and Gloeckner, 2005 [83] | Quasi-experimental | YES—no treatment | n = 48 11–12 years Pupils had tested for abnormal examination anxiety | ‘TorweY-C’—Postures, breathing, relaxation and another element such as massage, sensory exercises, meditation, imagery techniques and interactive activities 60 min × 15 total classes | Anxiety | Immediately after intervention, anxiety was reduced and remained stable until 3 months post-intervention. |

| Telles, Singh, Bhardwaj, Kumar and Balkrishna, 2013 [84] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 98 8–13 years (mean 10.5 years + 1.3) F = 38/M = 60 | Yoga—Postures, breathing, relaxation and chanting 45 min × 5 days a week for 3 months during school hours. | Self-esteem, academic performance, attention | Both groups showed increases in word scores, colour scores and colour-word scores. The yoga group showed an increase in total, general and parental self-esteem. Both groups showed improvements in academic performance and attention. |

| Tersonde Paleville and Immekus, 2020 [85] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—physical activity program called Minds in Motion (MiM) | n = 44 5–11 years (mean 7.2 years) F = 21/M = 27 | ‘Cosmic Kids Yoga Programme’—Postures, meditation and yoga games/activities | Academic performance, anxiety, attention | Although no statistical differences were found between CG and yoga groups across measures, both groups had increased academic skills after the intervention. |

| Thomas and Centeio, 2020 [100] | Mixed methods | YES—no treatment | n = 40 8 years F = 18/M = 22 | ‘Yoga Calm’—Postures, breathing, relaxation, mindfulness practice and social-emotional learning 20 min × 2 a week for 10 weeks plus shorter intervals of yoga poses, breathing and relaxation through the school day | Attention, anxiety, well-being | Participants expressed feeling ‘happier’ since yoga programme. The school teacher reported that children who were the most stressed and anxious had reduced anxiety and stress. Others became more concentrated and focused. |

| Velásquez, López, Quiñonez and Paba, 2015 [86] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—waitlist | n = 125 10–15 years No gender details | Developed around Satyananda Yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation and relaxation 120 min × 24 over 12 weeks in school | Depression, anxiety | At baseline, the yoga group had statistically significantly higher levels of depression compared to CG. Yoga group reported a decrease in their anxiety and depression levels, while CG experienced an increase in these indicators. |

| Verma and Shete, 2020 [87] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—no treatment | n = 66 11–15 years F = 18/M = 48 | ‘Kaivalydhama Yoga’—Postures, breathing, chanting 60 min × 6 times a week for 12 weeks in a residential school | Executive function | In executive function tests, a significant improvement was reported after yoga; however, no change was observed in CG. |

| Verma, Shete, Thakur, Kulkarni and Bhogal, 2014 [88] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—regular physical training | n = 82 11–15 years (mean 13.02) No gender details | ‘Kaivalydhama Yoga’—Postures, breathing, chanting | Memory | The yoga group showed a significant improvement in the memory of the figural information test. The remaining memory tests did not show any improvements or changes. The CG showed no improvements in any of the memory tests. |

| Vhavle, Rao and Manjunath, 2019 [89] | Randomised controlled trial | YES—traditional PE | n = 802 No age or gender details | Yoga—no intervention details 60 min × 5 days a week for 2 months | Executive function | Within groups, both CG and yoga significantly increased numerical executive function tests; however, there was no significant difference between groups. There was a significant increase in alphabetical executive function tests in the yoga group but not CG. |

| Wang and Hagins, 2016 [96] | Qualitative | NO | n = 74 (approx) 9–12 years No gender details | Yoga—Postures, breathing, meditation, relaxation and didactic/themed discussions 1/2 × a week across a full academic year | Self-esteem, anxiety, academic performance | Increased self-esteem was one of the main findings reported by focus groups. Increased academic performance was also noted by some students. |

| Outcome | Neurodiverse | Neurotypical |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 0/1 | 7/10 |

| Depression | 0 | 7/8 |

| Self-esteem | 0 | 7/7 |

| Self-concept | 2/2 | 1/2 |

| Psychological & Subjective Well-being | 2/2 | 12/15 |

| Resilience | 0 | 2/3 |

| Executive Function | 1/1 | 5/7 |

| Inhibition | 0 | 2/3 |

| Working Memory | 0 | 1/2 |

| Shifting | 0 | 0 |

| Attention | 1/2 | 15/15 |

| Academic performance | 3/3 | 12/13 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hart, N.; Fawkner, S.; Niven, A.; Booth, J.N. Scoping Review of Yoga in Schools: Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes in Both Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Youth Populations. Children 2022, 9, 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060849

Hart N, Fawkner S, Niven A, Booth JN. Scoping Review of Yoga in Schools: Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes in Both Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Youth Populations. Children. 2022; 9(6):849. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060849

Chicago/Turabian StyleHart, Niamh, Samantha Fawkner, Ailsa Niven, and Josie N. Booth. 2022. "Scoping Review of Yoga in Schools: Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes in Both Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Youth Populations" Children 9, no. 6: 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060849

APA StyleHart, N., Fawkner, S., Niven, A., & Booth, J. N. (2022). Scoping Review of Yoga in Schools: Mental Health and Cognitive Outcomes in Both Neurotypical and Neurodiverse Youth Populations. Children, 9(6), 849. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060849