Köbner and Pastia Signs in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Young Children: Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

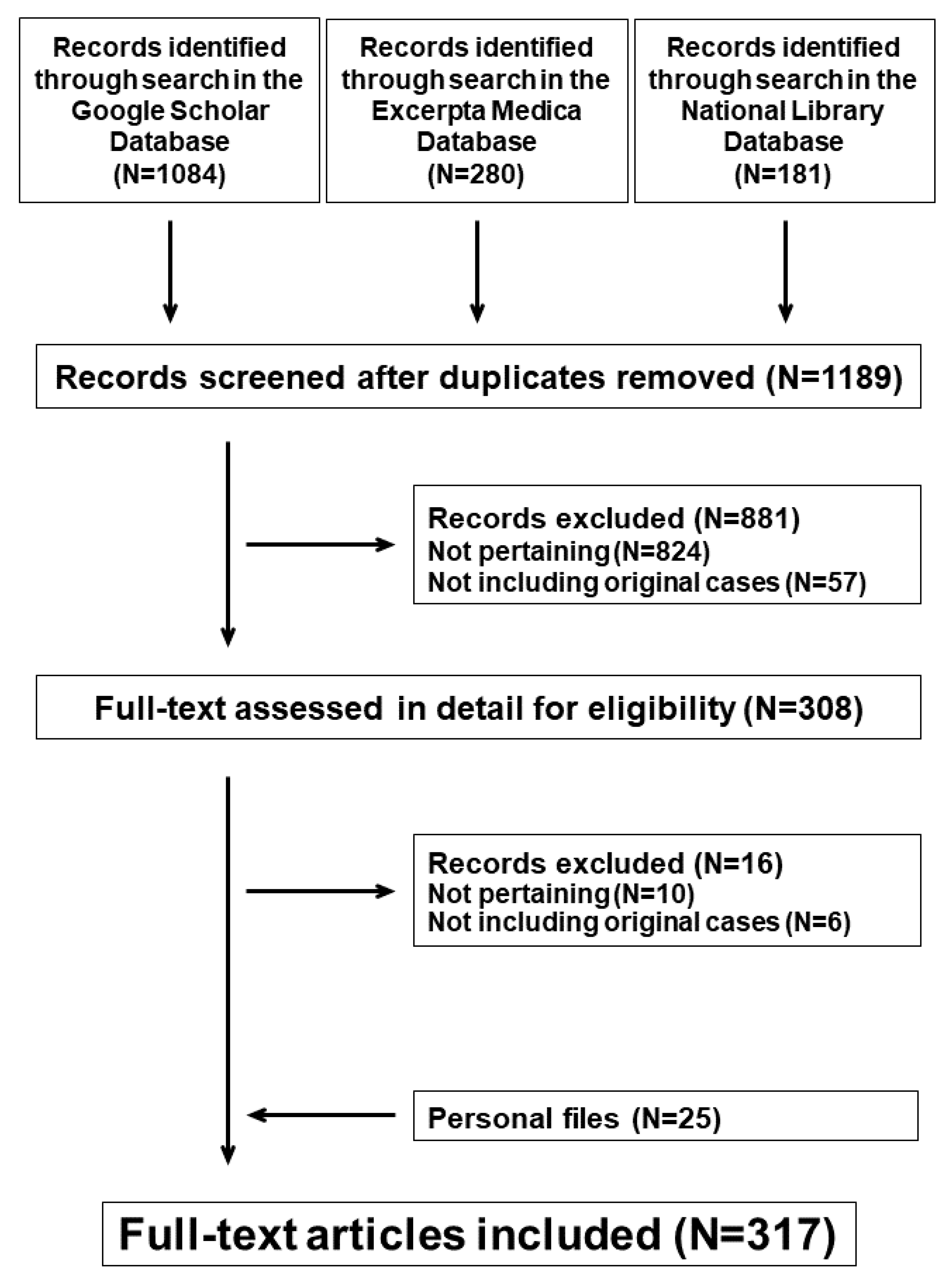

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Analysis

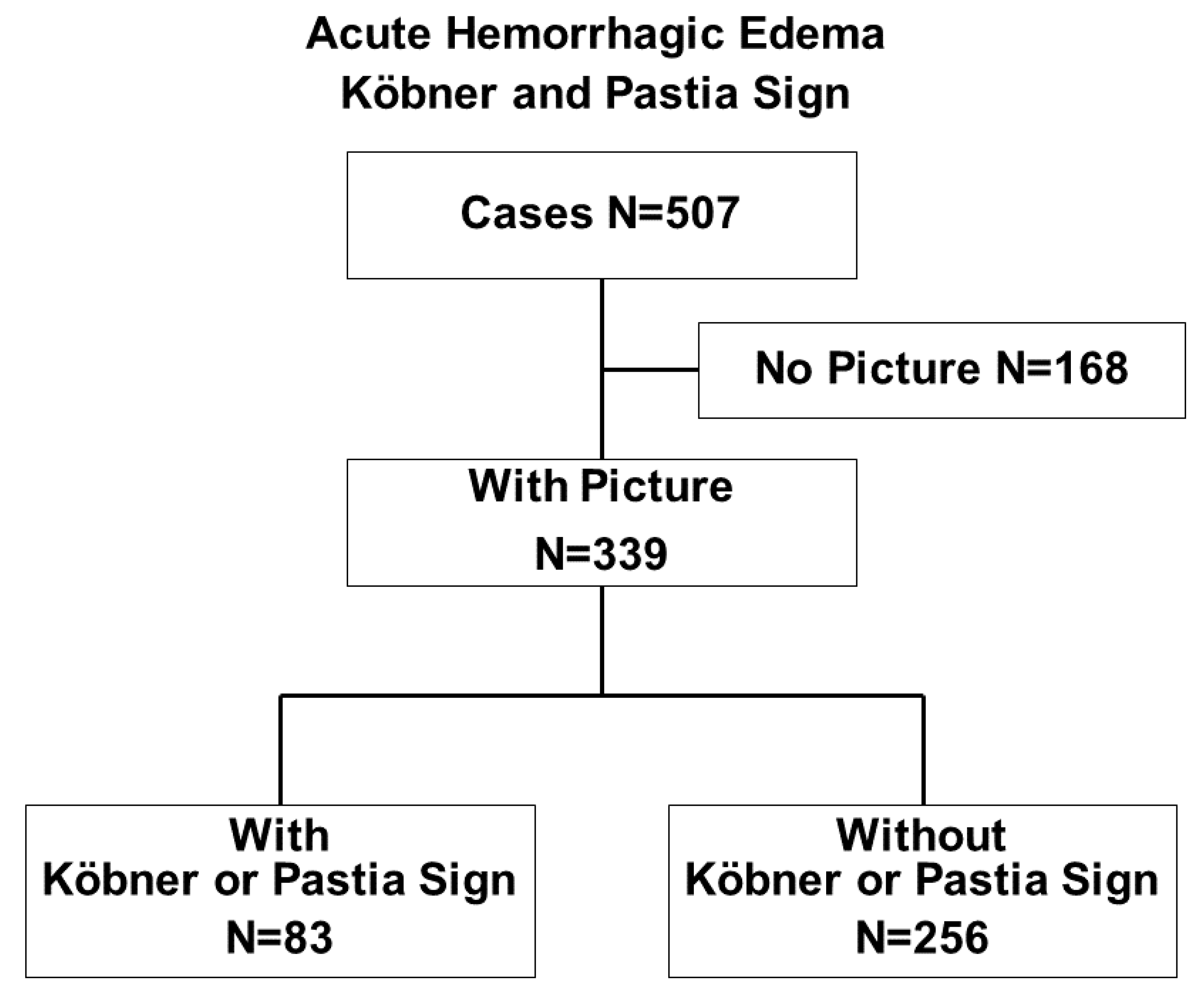

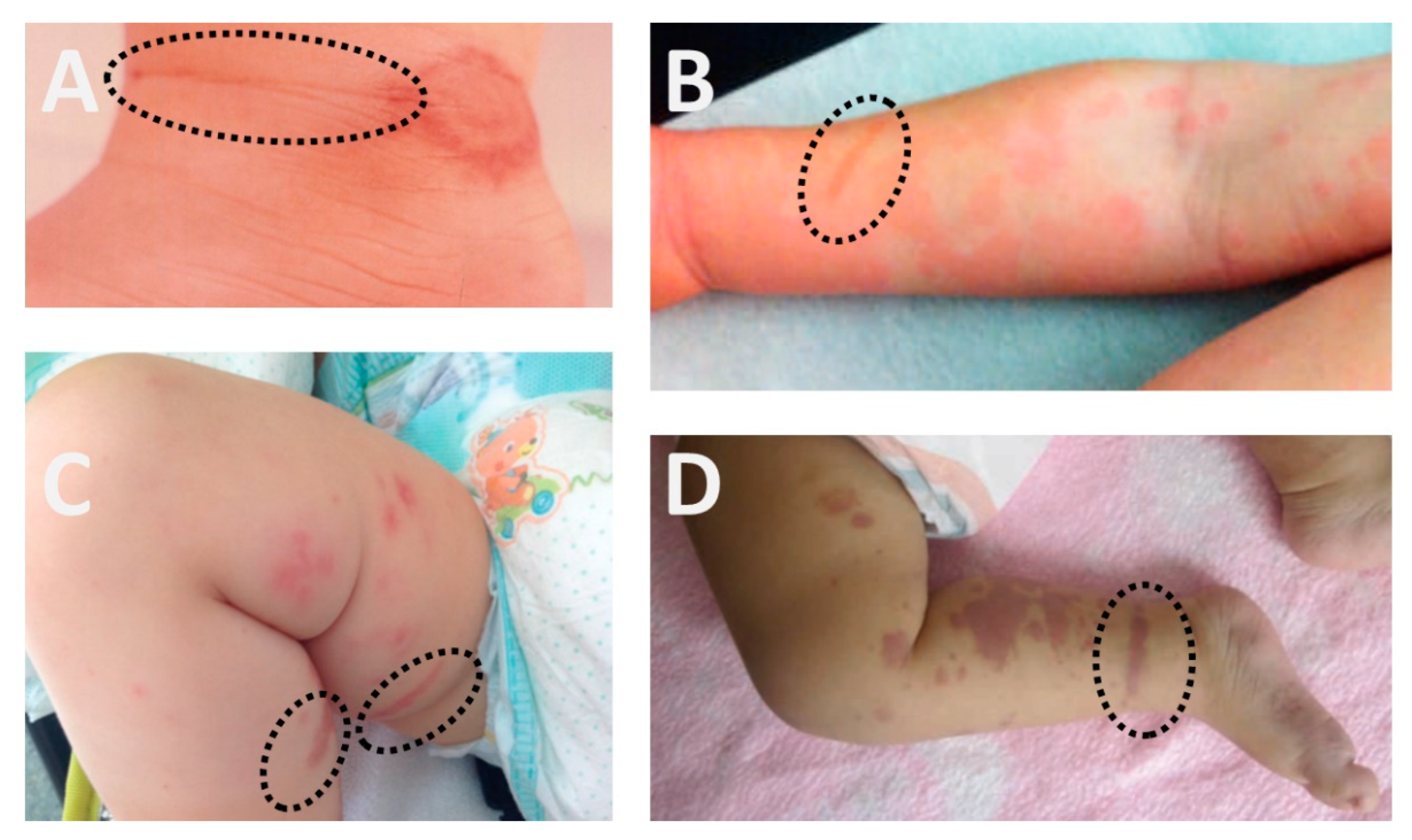

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ting, T.V. Diagnosis and management of cutaneous vasculitis in children. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 61, 321–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lava, S.A.G.; Milani, G.P.; Fossali, E.F.; Simonetti, G.D.; Agostoni, C.; Bianchetti, M.G. Cutaneous manifestations of small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitides in childhood. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 53, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinoldi, P.O.; Bronz, G.; Ferrarini, A.; Mangas, C.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Chelleri, C.; Lava, S.A.G.; Milani, G.P. Acute hemorrhagic edema: Uncommon features. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 85, 1620–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronz, G.; Rinoldi, P.O.; Lavagno, C.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Lava, S.A.G.; Vanoni, F.; Milani, G.P.; Terrani, I.; Ferrarini, A. Skin eruptions in acute hemorrhagic edema of young children: Systematic review of the literature. Dermatology 2021, 1–7, epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, G.; Shemer, A.; Trau, H. The Koebner phenomenon: Review of the literature. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2002, 16, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breese, B.B. Streptococcal pharyngitis and scarlet fever. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1978, 132, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, A.; Rahnama-Moghadam, S. Scarlatiniform rash caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Cureus 2020, 12, e8881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papi, M.; Didona, B. Unusual clinical presentations of vasculitis: What some clinical aspects can tell us about the pathogenesis. Clin. Dermatol. 1999, 17, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchetti, M.G. FMH Quiz 60. Paediatrica 2015, 26, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrègue, M.; Lesage, B.; Rossier, A. Edema agudo hemorragico del lactante (EAHL) (purpura en escarapela con edema postinfeccioso de Seidlmayer) y vascularitis alergica. Med. Cutanea 1974, 11, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, B.; Larrègue, M.; Bouillet, F.; Rossier, A. Oedème aigu hémorragique du nourrisson (purpura en cocarde avec oedème post-infectieux de Seidlmayer) et vascularité allergique. Ann. Pédiatr. 1975, 22, 599–606. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, Y.; Massé, R.; Le Fur, J.M.; Alix, D.; Herry, B.; Olivre, M.A. L’oedème aigu hémorragique de la peau du nourrisson: Étude clinique et nosologique. Ann. Pédiatr. 1976, 23, 653–666. [Google Scholar]

- Despert, F.; Fauchier, C.; Laugier, J. L’oedeme aigue hemorragique du nourrison: À propos d’une observation. Rev. Med. Tours 1977, 11, 729–732. [Google Scholar]

- Pierini, D.O.; García Diaz, R.; Pierini, A.M. Edema agudo hemorrágico del lactante. Púrpura en escarapela. Arch. Argent. Dermatol. 1977, 27, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Melinkovich, P. Schönlein-Henoch purpura misdiagnosed as suspected child abuse. A case report and literature review. JAMA 1986, 256, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, A.; Plantin, P.; Metz, C.; Guillet, G. Oedème aigu hémorragique du nourisson: À propos d’un cas e Discussion de l’intérêt du dosage du facteur XIII de la coagulation. Nouv. Dermatol. 1987, 6, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgojo Lopéz, M.; Vélez Garcia-Neto, A.; López-Barrantes, V.; González Mediano, I.; Zambrano Zambrano, A. Edema agudo hemorrágico del lactante. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1991, 82, 648–652. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, M.; Stieh, J. Infantiles akutes hämorrhagisches Ödem. Z. Hautkr. 1992, 67, 458–459. [Google Scholar]

- Sipahi, T.; Yöney, A.; Tuna, F.; Karademir, S. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Anatol. J. Pediatr. 1992, 2, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Amitai, Y.; Gillis, D.; Wasserman, D.; Kochman, R.H. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in infants. Pediatrics 1993, 92, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbaud, A.; Gillet-Terver, M.N.; Schmutz, J.L.; Weber, M. Cas pour diagnostic: Oedème aigu hémorragique du nourrisson. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 1995, 122, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Çaliskan, S.; Tasdan, Y.; Kasapçopur, Ö.; Sever, L.; Tunnessen, W.W. Picture of the month: Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1995, 149, 1267–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Criado, P.R.; Sakai Valente, N.Y.; Jardim Criado, R.F.; Sittart, J.A.S.; Sawaya, S. Edema agudo hemorrágico do lactente. An. Bras. Dermatol. 1996, 71, 403–406. [Google Scholar]

- Mássimo, J.A.; Giglio, N.; Cotton, A.; Goldfarb, G. Cual es su diagnostico? Edema agudo hemorragico del lactante. Rev. Hosp. Ninos 1996, 38, 287–288. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, G.; Kinzlansky, V.; Kahn, A.; Damilano, G. Pathological case of the month: Infantile acute hemorrhagic edema. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1997, 151, 523–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, A.; Pezzarossa, E.; Zambelloni, C.; Lupi, A.; Lazzari, G.B.; Rossoni, R. Case of the month: A girl with oedema and purpuric eruption. Diagnosis: Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1997, 156, 813–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonggryp, L.A.; Todd, G. Acute hemorrhagic edema of childhood (AHE). Pediatr. Dermatol. 1998, 15, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.R.; Saulsbury, F.T. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy associated with pneumococcal bacteremia. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1999, 18, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Falcón, F.; García Consuegra, J. Gastroenteritis por Campylobacter jejuni y edema agudo hemorrágico del lactante. Pediátrika 2000, 20, 254–256. [Google Scholar]

- Carbajal, R.L.; Zarco, R.J.; Rodríguez, H.R.; Reynes, M.J.N.; Barrios Fuentes, R.; Luna, F.M.; Villegas, V.E. Edema hemorrágico agudo y púrpura de Henoch-Schönlein ¿Son una misma enfermedad en los lactantes? Rev. Mex. Pediatr. 2000, 67, 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- Dönmez, O.; Memesa, A. Akut ýnfantýl hemorajýk ödem: Üç olgunun takdýmý. ADÜ Týp. Fakültesi Derg. 2001, 2, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeer, M.H.; Stoof, T.J.; Kozel, M.M.A.; Blom, D.J.M.; Nieboer, C.; Sillevis Smitt, J.H. Acuut hemorragisch oedeem van de kinderleeftijd en het onderscheid met Henoch-Schönlein-purpura. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2001, 145, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ballona, R. Pápulas purpúricas en récien nacido. Dermatol. Peru 2002, 12, 231–233. [Google Scholar]

- Çaksen, H.; Odabas, D.; Kösem, M.; Arslan, S.; Öner, A.F.; Atas, B.; Akçay, G.; Ceylan, N. Report of eight infants with acute infantile hemorrhagic edema and review of the literature. J. Dermatol. 2002, 29, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K.; Yabunami, H.; Hisanaga, Y. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy associated with cytomegalovirus infection. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 1254–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Goraya, J.S.; Poddar, B.; Parmar, V.R. Acute infantile hemorrhagic edema and Henoch-Schönlein purpura overlap in a child. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2002, 19, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Coelho, S. Edema agudo hemorrágico do lactente. Acta Pediátr. Port. 2004, 35, 149–151. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, M.R.; Chung, H.J.; Lee, J.H. A case of acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Yonsei Med. J. 2004, 45, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilian Pérez, C.; Alicia Benavides, M.; Bárbara Barrientos, F.; Cristian Deza, E.; Cristó bal Guixe, A.; Gonzalo Mendoza, L. Edema hemorrágico agudo del lactante. Rev. Chil. Pediatr. 2006, 77, 599–603. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, L.M.; Aldama, O.; Rivelli, V.; Gorostiaga, G.; Mendoza, G.; Aldama, A. Edema agudo hemorrágico del lactante. Reporte de un caso. Dermatol. Pediatr. Lat. 2007, 5, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cicero, M. Rash decisions: Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy in a 7-month-old boy. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2008, 24, 501–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alp, H.; Artaç, H.; Alp, E.; Reisli, I. Acute infantile hemorrhagic edema: A clinical perspective (report of seven cases). Marmara Med. J. 2009, 22, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- El Hafidi, N.; Allouch, B.; Benbrahim, F.; Mahraoui, C. L’oedème aigu hémorragique du nourrisson: Une vascularite benigne et récidivante. J. Pediatr. Pueric. 2009, 22, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergüven, M.; Karaca Atakan, S. Infantile hemorrhagic edema due to parvovirus B19 infection. Çocuk Derg. 2009, 9, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Karremann, M.; Jordan, A.J.; Bell, N.; Witsch, M.; Dürken, M. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: Report of 4 cases and review of the current literature. Clin. Pediatr. 2009, 48, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menteş, S.E.; Taşkesen, M.; Katar, S.; Günel, M.E.; Akdeniz, S. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Dicle. Univ. Tip. Fakul. Derg. 2009, 36, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli, A.A.; Castellani, M.S.; Gerardini, E.; Fioretti, P.; Castellucci, G. Edema emorragico acuto del lattante: Descrizione di un caso clinico. Riv. Ital. Pediatr. Osped. 2009, 2, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Halicioglu, O.; Akman, S.A.; Sen, S.; Sutcuoglu, S.; Bayol, U.; Karci, H. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: A case report. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2010, 27, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.; Lira, S.; Zilhão, C. Edema hemorrágico agudo da infância—Dois casos clínicos. Birth Growth Med. J. 2010, 19, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cacharrón Caramés, T.; Díaz Soto, R.; Suárez García, F.; Rodríguez Valcárcel, G. Edema hemorrágico agudo del lactante. An. Pediatr. 2011, 74, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behmanesh, F.; Heydarian, F.; Toosi, M.B. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: Report of two cases report. Iran J. Blood Cancer 2012, 4, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Boos, M.D.; McMahon, P.; Castelo-Soccio, L. Acute onset of a hemorrhagic rash in an otherwise well-appearing infant. J. Pediatr. 2012, 161, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabanillas-Becerra, J.; Pérez-del Arca, C.; Vera, C.; Barquinero-Fernández, A. Edema agudo hemorrágico del lactante. Dermatol. Peru 2012, 22, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fotis, L.; Nikorelou, S.; Lariou, M.S.; Delis, D.; Stamoyannou, L. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: A frightening but benign disease. Clin. Pediatr. 2012, 51, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhammadi, A.H.; Adel, A.; Hendaus, M.A. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: A worrisome presentation, but benign course. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 6, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Januário, G.; Maia, P. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2012008145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco Soto, J.V.; Delgado, A.; Deivis, J.; Lidiz, M.M.; Peñuela, O. Enfermedad de Finkelstein. Reporte de un caso. Arch. Venez. Pueric. Pediatr. 2013, 76, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Estoup, M.V.; Hernández, M.; Soliani, A.; Abeldaño, A. Edema y lesiones purpúricas en miembros inferiores de un lactante. Dermatol. Pediatr. Lat. 2013, 11, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann Holzinger, I.I.; Neuhaus, T.J.; Portmann, S. Kokardenpurpura, rote Ohren und schmerzende Füsse bei kleinen Kindern. Schweiz. Med. Forum 2014, 14, 545–546. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhoury, S.R.; Ganguly, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Samanta, M.; Datta, K. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Indian J. Pediatr. 2014, 81, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkrigg, S.; Johnson, A.; Flynn, J.; Thom, G.; Wright, H. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy in a 5-week-old boy referred to the Child Protection Unit. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2014, 50, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Sazlly Lim, S.; Shamsudin, N. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy with bullae and koebnerisation. Malays. Fam. Physician 2014, 9, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nacaroğlu, H.T.; Saygaz, S.; Sandal, Ö.S.; Karkıner, C.S.Ü.; Yıldırım, H.T.; Can, D. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy after vaccination: A case report. J. Pediatr. Inf. 2014, 8, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden Rueda, C.; Clavero Montañés, N.; Berdún Cheliz, E.; Calvo Ferrer, C.; Visiedo Fenollar, A.; Sánchez Gimeno, J. Edema agudo hemorrágico. Bol. Pediatr. Arag. Rioj. Sor. 2014, 44, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Argyri, I.; Korona, A.; Mougkou, K.; Vougiouka, O.; Tsolia, M.; Spyridis, N. Photo quiz. An infant with purpuric rash and edema. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1553,1624–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Breda, L.; Franchini, S.; Marzetti, V.; Chiarelli, F. Escherichia coli urinary infection as a cause of acute hemorrhagic edema in infancy. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2015, 32, e309–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, M.; Dhariwal, D.K. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy (AHOI): A case report. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2015, 14 (Suppl. 1), 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lacerda, A.C.M.; Silva, S.A.; Rafael, M.S.; Correia, S.A.M.; Batista, C.B.; Castanhinha, S.I.F. Edema hemorrágico agudo da infância: Uma vasculite com bom prognóstico. Sci. Med. 2015, 25, 21381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, G. Acute hemorrhagic edema: Rare variety of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Indian J. Paediatr. Dermatol. 2016, 17, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caixeta, M.F.; Lima, J.S.; Zandonaide, A.G.B. Acute hemorrhagic edema of childhood: Case report and comparison with meningococcemia. Resid. Pediátr. 2016, 6, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstathiou, E.; Papamichalopoulou, S.; Georgiou, G.; Hadjipanayis, A. Rapid onset of purpuric rash in an otherwise healthy 6-month-old infant. Clin. Pediatr. 2016, 56, 1377–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, P.A.; Aguiar, C.; Dinis, M.J.; Ramos, S. Edema agudo hemorrágico do lactente—A (re) conhecer. Birth Growth Med. J. 2016, 25, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Socarras, J.A.; Velosa, Z.A.F. Edema agudo hemorrágico de la infancia. Lesiones alarmantes de un cuadro benigno. Reporte de caso. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2017, 115, e432–e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez-Alvarez, S.; Barbosa-Moreno, L.; Ocampo-Garza, J.; Ocampo-Candiani, J. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (Finkelstein’s disease): Favorable outcome with systemic steroids in a female patient. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92, 150–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, E.Ü.; Öz, N.A.; Temizkan, R.C.; Hıdımoğlu, B.; Kocabay, K. Bad-looking, good-natured disease: Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. J. Curr. Pediatr. 2017, 15, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van der Heggen, T.; Dhont, E.; Schelstraete, P.; Colpaert, J. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: A dramatic presentation with a benign course. Belg. Assoc. Pediatr. 2017, 19, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, N.; Taneja, S.; Bihari, S.; Verma, A. Acute hemorrhagic edema in a nursing infant—An unusual diagnosis. Indian J. Child Health 2018, 5, 310–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, M.; Conrieri, M.; Raffaldi, I.; Pagliardini, V.; Urbino, A.F. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: Still a challenge for the pediatrician. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2018, 34, e28–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speirs, L.; McVea, S.; Little, R.; Bourke, T. What is that rash? Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 2018, 103, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, E.; Scavone, M.; Stefanelli, E.; Talarico, V.; Zampogna, S.; Galati, M.C.; Raiola, G. Case report: Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (Seidlmayer purpura)—A dramatic presentation for a benign disease. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Muro, C.; Esteban-Zubero, E. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infant: A case report. Mathews J. Pediatr. 2019, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıçaslan, Ö.; Yıldız, R.; Engin, M.M.N.; Büyük, N.; Temizkan, R.C.; Özlü, E.; Kocabay, K. Acute infantile hemorrhagic edema clinic: Two case reports. J. Acad. Res. Med. 2019, 9, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, G.R.; Protásio, I.R.; Fioretto, J.R.; Cardoso, L.F.; Romero, F.R.; Martin, J.G. Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy: A case series of three cases. Indian J. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.; Rothman, I.; Mannix, M.K.; Islam, S. Infant with a rapidly progressing rash. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e239353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, N.E.; Keukens, L. Indrukwekkend huidbeeld bij een gezond kind. Huisarts Wet. 2021, 64, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Bux, D.; O’Connell, M. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy: First report of a rare small vessel vasculitis in the neonatal period. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, E.; Sayad, A.; Alameddine, L.; El-Haddad, K.; Tannous, Z. Mycoplasma pneumonia and atypical acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 41, 266.e3–266.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, B.M.; Lobato, M.B.; Santos, E.; Garcia, A.M. Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy as a manifestation of COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e241111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, G.P.; Lava, S.A.G.; Ramelli, V.; Bianchetti, M.G. Prevalence and characteristics of nonblanching, palpable skin lesions with a linear pattern in children with Henoch-Schönlein syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, C.; Camozzi, P.; Gennaro, V.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Scoglio, M.; Simonetti, G.D.; Milani, G.P.; Lava, S.A.G.; Ferrarini, A. Atypical bacterial pathogens and small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis of the skin in children: Systematic literature review. Pathogens 2021, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, M.L.; Steele, R.W. Group A Streptococcus. Pediatr. Rev. 2018, 39, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, L.W. Hemorrhagic purpura in scarlet fever—A report of two cases. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1938, 56, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, G.; Moltrasio, C.; Berti, E.; Marzano, A.V. Skin manifestations associated with COVID-19: Current knowledge and future perspectives. Dermatology 2021, 237, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| without | with | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Köbner or Pastia Sign | Köbner and Pastia Signs | Köbner Sign | Pastia Sign | |||

| N | 256 | 83 | 8 | 24 | 51 | |

| Males:females, N | 176:80 | 60:23 | 7:1 | 14:10 | 39:12 | |

| Age, months | 11 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18] | 11 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] | 11 [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] | 11 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] | 11 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] | |

| Precursor | ||||||

| Infection, N | 222 | 69 | 7 | 20 | 42 | |

| Vaccine, N | 13 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Uncommon features, N | 56 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 8 | |

| Long disease duration, N | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Localization | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower legs, N | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| Thigh, waistline, groin, N | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Arms, N | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Back, N | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Face, N | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Feet, N | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Localization | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle, feet, N | 28 | 3 | 31 |

| Cubital fossa, ellbow, N | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Thigh, waistline, groin, N | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Back, knee, popliteal fossa, N | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Wrist, N | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Axilla, N | 4 | 2 | 6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bronz, G.; Consolascio, D.; Bianchetti, M.G.; Rinoldi, P.O.; Betti, C.; Lava, S.A.G.; Milani, G.P. Köbner and Pastia Signs in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Young Children: Systematic Literature Review. Children 2022, 9, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020265

Bronz G, Consolascio D, Bianchetti MG, Rinoldi PO, Betti C, Lava SAG, Milani GP. Köbner and Pastia Signs in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Young Children: Systematic Literature Review. Children. 2022; 9(2):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020265

Chicago/Turabian StyleBronz, Gabriel, Danilo Consolascio, Mario G. Bianchetti, Pietro O. Rinoldi, Céline Betti, Sebastiano A. G. Lava, and Gregorio P. Milani. 2022. "Köbner and Pastia Signs in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Young Children: Systematic Literature Review" Children 9, no. 2: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020265

APA StyleBronz, G., Consolascio, D., Bianchetti, M. G., Rinoldi, P. O., Betti, C., Lava, S. A. G., & Milani, G. P. (2022). Köbner and Pastia Signs in Acute Hemorrhagic Edema of Young Children: Systematic Literature Review. Children, 9(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9020265