Abstract

Socioeconomically disadvantaged populations are at greater risk of adopting unhealthy behaviours and developing chronic diseases. Adolescence has been identified as a crucial life stage to develop lifelong healthy behaviours, with schools often suggested as the ideal environment to foster healthy habits. Health literacy (HL) provides a possible solution to promote such healthy behaviours. The aim of this study was to review school-based HL-related interventions targeting socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents and to identify effective intervention strategies for this population. Searches were performed in six databases. Inclusion criteria included age: 12–16; the implementation of a school-based intervention related to HL aimed at socioeconomically disadvantaged populations; an intervention focused on: physical activity (PA), diet, mental health, substance abuse or sleep. Forty-one articles were included, with the majority focusing on PA and diet (n = 13), PA (n = 9) or mental health (n = 7). Few interventions focused solely on substance abuse (n = 2) or sleep (n = 1), and none targeted or assessed HL as an outcome measure. There was huge heterogeneity in study design, outcomes measures and effectiveness reported. Effective intervention strategies were identified that can be used to guide future interventions, including practical learning activities, peer support and approaches targeting the school environment, the parents or that link the intervention to the community.

1. Introduction

Morbidity and mortality rates from obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, are rapidly rising [1,2]. Poor lifestyle behaviours, including low levels of physical activity (PA), high levels of sedentary behaviour, poor dietary habits, substance abuse, poor sleeping habits and mental illness, are said to be large contributors to the NCD burden [3,4,5]. This not only places a heavy burden on society but also on limited health resources [6].

Furthermore, there is extensive literature describing socioeconomic health inequalities in terms of morbidity and mortality. Populations from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to avoid unhealthy behaviours [7], and are consequently more likely to develop chronic diseases [8]. There is, therefore, a growing need for the promotion of a healthy lifestyle as a form of primary prevention, particularly in low socioeconomic populations [9].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health literacy (HL) as the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of an individual to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health [10]. The concept of HL has evolved from what was initially a focus on an individual’s ability to read and understand health information, to focusing on factors that affect an individual’s knowledge, motivation and competencies in relation to health [11,12]. HL has been identified as a personal resource that empowers an individual to make informed health decisions in everyday life and has been acknowledged as a key determinant of health [13,14]. Numerous studies have reported a positive association between high levels of HL, better lifestyle behaviours and better health outcomes in children and adolescents [15,16]. This is highlighted in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children survey, which reported HL as one of the major contributing factors leading to health differences [17]. Research indicates that HL is determined by level of education and socioeconomic indicators, with more affluent individuals reporting higher levels of HL [15,18]. Enhancing HL levels in low socioeconomic populations may, therefore, offer a means to reach greater health equity [19]. The WHO has recognised the potential role of improved HL in preventing and reducing NCDs by empowering citizens to manage their own health [13]. Consequently, the WHO has engaged in numerous actions to promote health through an improvement in HL [13,20], and has identified the educational sector as the most important setting for teaching and learning HL in early life [13].

Adolescence is a time period when individuals begin to achieve greater autonomy [21]. Lifestyle behaviours are developed, established, and ultimately track into adulthood [22]. Adolescence is also a period when health behaviours and social determinants, such as the ability to stay in education, can have lasting impacts on health equity across the life course [23]. Thus, this time period is increasingly recognised as challenging, but also as a window of opportunity to improve HL in order to promote positive health behaviours, and consequently reduce the risk of lifestyle-related diseases [24].

A systematic review investigating approaches to behaviour change interventions in young people from disadvantaged backgrounds found that successful interventions incorporated educational components [25], as education has been proven to improve attitudes, develop HL and change health behaviours in youth [26,27]. Furthermore, lifelong behaviours that are developed during adolescence are influenced by educational, biological, cognitive, and socioecological factors [28]. As a result, the school environment has been identified as the ideal setting for interventions to promote health behaviours and reduce NCD risk [29,30]. In addition, it has been suggested that health and education are synergistic [31]; individuals who are well educated are more likely to maintain good health [32], and students with better health are more likely to attain a higher level of education [33]. This relationship between education and health forms the basis of the WHO’s Health-Promoting Schools (HPS) framework, an approach focused on promoting health by addressing the whole school environment [34]. Creating a healthy school environment can, therefore, benefit not only the health and well-being, but also the academic performance of a student [34].

School-based health interventions, however, have reported mixed levels of success [35]. A lack of connection to the fundamental objectives of the schools may be one possible reason for this [36]. To maximise effectiveness, it has been recommended that school-based interventions adopt comprehensive, integrative approaches to health promotion which target both the school environment, and the individual’s attitudes and behaviours [34]. Interventions should also be developed and implemented with a range of actors (students, school staff and community members) [37] and be tailored specifically to the local context [38] to ensure that the needs of the target population are met. This is particularly important when it comes to socioeconomically disadvantaged populations [39]. Socioeconomically disadvantaged populations are not only more likely to have poorer health behaviours, but they are also more likely to have poorer health outcomes following interventions and implementation of government policy changes, when compared to more affluent groups [40,41]. It has even been suggested that poor outcomes following interventions may actually increase health inequalities [42], further emphasising the need to tailor health interventions for disadvantaged populations; an approach which has been proven effective [43,44].

Although previous work has provided recommendations on effective strategies for the implementation of school-based health interventions in the general population, there is a lack of research focusing on interventions specifically targeting adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Of specific interest are interventions aimed at adolescents aged 12–16, as this is typically a time period where adolescents in Ireland and the United Kingdom attend their junior years of post-primary education, creating a practical and pragmatic timepoint to intervene during adolescence [23]. The aim of this paper is to review HL-related school-based interventions in adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds and to identify effective intervention strategies to improve HL for this population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was registered with PROSPERO: The international prospective register of systematic reviews (REF: CRD42020184410) and adhered to the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [45].

2.1. Study Selection Criteria

Inclusion:

Studies identified through the literature search were included if they:

- Included typical adolescents with a reported mean age between 12 and 16 years;

- Self-reported that the participants were from a socioeconomically disadvantaged (or equivalent) background;

- Included the implementation of an intervention related to health literacy (increases health knowledge, understanding, awareness, motivation, confidence) in at least one of the following areas: physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary habits, sleeping habits, mental health or substance abuse;

- Included school-based interventions, interventions that could be feasibly implemented in a school setting or interventions that could be linked to a school curriculum;

- Aimed to increase health knowledge/comprehension, understanding, behaviour, value, well-being, motivation, self-efficacy or self-monitoring in relation to any of the following domains: physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary habits, sleeping habits, mental health or substance abuse.

Exclusion:

Studies identified in the literature search were excluded if:

- 6.

- They included special populations (e.g., children with learning difficulties, pregnant adolescents, exclusively obese individuals, or those with a specific health condition);

- 7.

- The intervention did not include an educational element or a component targeting health literacy (increases health knowledge, understanding, awareness, motivation, confidence);

- 8.

- They were book chapters, case studies, student dissertations, conference abstracts, review articles, meta-analyses, editorials, protocol papers or systematic reviews;

- 9.

- They were not published in English or in a peer-reviewed journal;

- 10.

- The full-text article was not available.

For full the PICO statement, see Appendix A.

2.2. Information Sources, Search Strategy and Study Selection

Six electronic databases were searched—MEDLINE/PubMed, ERIC, CINAHL, PsychINFO, and EMBASE—to identify relevant evidence. ‘English’ and ‘peer reviewed’ filters were marked on all searches. The search strategy was developed using Boolean operators (AND/OR), incorporating the relevant terms (Appendix B). The search was not limited to any publication time frame. The search was conducted between June and August 2020. All records were exported to Mendeley reference managing software for screening and all duplicates were removed.

Two reviewers (C.S. and H.R.G.) independently assessed the eligibility of the studies. Following title and abstract screening, full-text copies of potentially relevant studies were obtained and screened for full-text inclusion. In the case of disagreement, a third author (S.B. or J.I.) was contacted for discussion until consensus was reached.

2.3. Data Collection

Following the screening process, the data were extracted into table format. Study data relating to study information, sample information, purpose of study, intervention description, measurement technique, reported outcome variables, intervention fidelity and intervention quality was extracted. One reviewer (C.S.) entered the data from the included articles into an evidence table, and the second reviewer (H.R.G.) then examined the articles and edited the table entries as needed for accuracy.

2.4. Quality Appraisal

Each study was assessed for the risk of bias using a modified version of the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [46]. The tool was further adapted to remove performance bias as it was deemed inappropriate for the context of this study. Each study was examined for selection bias, attrition bias, detection bias and reporting bias, and ranked as ‘low risk’ or ‘high risk’ for each. It was marked ‘unclear’ if there was insufficient information to make an assessment and marked ‘not applicable’ if the bias could not be determined based on the design of the study in question. A narrative overview of included interventions is also included.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

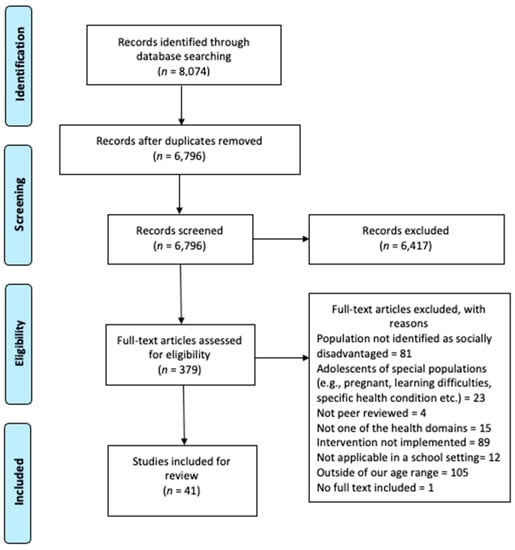

Figure 1 below details the search and screening process. The literature search yielded 8074 publications; after removing 1908 duplicates, 6796 publications were subsequently screened. Of these publications, 6417 were excluded based on title and abstract because they did not fulfil one or more of the inclusion criteria. The remaining 379 publications were retrieved for full-text review. A total of 338 failed to meet the inclusion criteria. The main reasons for excluding full texts were that the intervention targeted a population which was outside of the age range, the intervention was not implemented with populations which were socioeconomically disadvantaged. Finally, 41 publications were included for review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The study characteristics are summarised in Table 1 below. Among the 41 studies, 22 were based in the United States [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], six in Australia [70,71,72,73,74,75], four in Brazil [76,77,78,79], two in Sweden [80,81], two in India [82,83] and one each in Belgium [84], Chile [85], Spain [86] and Canada [87]. The year of publication ranged from 1996 [59] to 2020 [76], with the majority published in the last decade (n = 35). A total of 22 studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [47,48,51,52,55,58,59,63,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,82,85,86], ten employed pre-test-post-test quasi-experimental designs [49,53,62,64,65,66,69,79,80,84], four employed a single group pre-test–post-test designs [54,56,61,83], three were post-test qualitative evaluations [57,81,87], and the remaining two adopted cross-sectional designs [50,60]. All studies assessed the interventions using quantitative techniques, with the exception of five which employed mixed methods [49,54,69,86,87], and three that used qualitative analysis [57,60,81]. The sample size ranged from 15 [69] to 13,035 [82]. Twenty-eight of the studies looked at mixed-gender samples, while four focused only on males, and nine targeted females only.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

3.3. Quality Appraisal

The quality appraisal of the included studies is summarised in Table 2. Many studies were reported as ‘unclear risk’ as they did not provide adequate detail to assess the level of bias. Furthermore, studies which were not RCTs could not be assessed for selection bias as there was no random allocation. Of the studies that were assessed for selection bias, nine reported as ‘low risk’ across both assessments. Due to the lack of information, 15 of studies were reported as having an ‘unclear risk’ of detection bias. Of the remaining studies, seven were reported as ‘high risk’ and 19 as ‘low risk’. The majority (n = 35) were scored as ‘low risk’ for attrition bias, with two reported as ‘high risk’. Reporting bias was reported as ‘low risk’ in all included studies.

Table 2.

Quality Appraisal.

3.4. Intervention Characteristics

The intervention characteristics are detailed in Table 3 below. The largest group of interventions focused on PA and diet (n = 13) [49,55,64,65,66,67,69,70,71,77,81,84,86], followed by PA (n = 8) [47,48,58,61,73,74,75,76,80] and mental health (n = 7) [51,53,56,72,82,83,85]. The remainder targeted diet (n = 4) [54,60,62,78]; substance abuse (n = 2) [50,68]; PA, diet, substance abuse and mental health [59]; mental health and sleep [64]; PA, diet and substance abuse [52]; Sleep [57]; mental health and PA [87] and PA, diet and mental health [79]. Interventions were delivered by a wide range of people. The duration of the interventions ranged from a single session [55] to a three-year program [72]. Twenty of the interventions incorporated a behavioural theory into the design [47,48,52,54,55,58,61,64,65,66,67,70,71,73,74,75,76,85,87], with 12 of these underpinning their intervention strategies with multiple theories [47,48,54,55,64,65,66,67,73,74,75,76,77,78]. Twenty-three of the 41 interventions did not measure implementation fidelity.

Table 3.

Intervention Characteristics.

The majority of outcomes associated with the included interventions were concerned with health-related behaviours [50,52,54,55,56,59,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,73,74,76,78,80,84,86]. Other outcomes included psychosocial function [51,53,54,55,56,63,68,72,74,78,83,84,85], health-related knowledge [49,52,59,68,69], physical measures (body composition, physical fitness and biochemical measures) [47,59,63,67,70,71,73,77,78] and the cohort’s evaluation of the intervention [57,60,69,81,84,87]. The majority of studies used multi-component interventions (n = 30).

3.5. Intervention Results

In the interventions targeting both PA and diet, the behavioural outcomes reported were mixed. Five of the interventions improved both PA levels and dietary habits significantly [55,65,66,69], whereas two observed no significant improvement in either behaviour [64,84]. In the interventions aiming to improve PA and nutrition knowledge, both were effective (no significance level reported) [49,69]. Interventions targeting changes in anthropometric measures, such as BMI and body composition, also showed mixed levels of effectiveness. One intervention did not improve any measure of anthropometry [77], while another significantly improved body fat percentage but not BMI [70]. Furthermore, one significantly improved the percentage of individuals who were overweight or obese but did not improve total fat percentage, fat mass or fat free mass of participants [67], and finally Lubans et al. [71] improved BMI and body fat percentage slightly, but not significantly. The two interventions targeting psychosocial correlates associated with PA and dietary habits resulted in significant improvements [55,84]. Interventions which assessed the student’s perception of the intervention displayed positive responses [55,81].

In the interventions targeting PA only, five targeted behavioural outcomes (levels of PA). Four of which were unsuccessful in improving PA levels in their targeted cohorts [58,73,74,80], and one observed a significant improvement in girls but not in boys [61]. Health-related quality of life, however, was significantly improved in one these interventions [74] and muscular fitness in another [73]. Furthermore, interventions focused on reducing screen time did not observe any positive changes in behaviour [76]. Interventions assessing anthropometric measures had higher levels of success, with one study reporting a significant reduction in weight and BMI among the intervention group [75], while another observed a significant reduction in body fat percentage [73] and one observed modest positive changes in body fat percentage [47]. An intervention assessing the dose, reach and fidelity reported positive findings on all three variables [48].

The majority of the mental health interventions targeted psychological functioning, with the authors reporting mixed levels of success. Depressive symptoms were measured in two interventions—one reporting a non-significant improvement [51] and the other finding no intervention effects [85]. In addition, Schleider et al. (2019) [51] reported no improvement in social anxiety symptoms following the intervention. Similarly, Dray et al. [72] found no significant differences between the control and intervention group’s internalising problems, externalising problems and prosocial behaviour scores following the intervention. In a park-based intervention, results showed no significant improvements in parent-reported social skills or problem behaviours. However, staff-reported findings highlighted significant improvements in both problem behaviours and social skills at follow up [56]. In other interventions targeting mental health, social, emotional and academic performance [53], attention and self-efficacy [83], and school climate [82] were significantly increased.

Interventions specifically targeting diet had varied levels of success. Three programs targeted dietary behaviours specifically. One intervention reported a significant increase in the intake of fruit and vegetables and a statistically insignificant decrease in highly processed foods, compared with baseline [54]. Significant increases, however, were seen in psychosocial mediators, and qualitative assessments suggest that the intervention promoted skill building, but environmental barriers made these difficult to use. The two other interventions targeting dietary behaviours reported significant improvements as a result of the interventions [62,78]. School nutrition practice and policy was also significantly improved in the intervention by Alaimo et al. [62]. Finally, one intervention aimed to measure the students’, teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of the intervention, and to identify attributes that were highly valued within [60]. Four key themes ((1) development of life skills, (2) food and health, (3) family and community, and (4) experiential and participatory learning environment) were identified, and all stakeholders positively appraised the intervention.

Both interventions solely targeting substance abuse aimed to improve behavioural outcomes. An intervention by Robinson et al. [50] targeting a reduction in cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and marijuana use reported significant reductions in cigarette and marijuana use, but not in alcohol consumption. Vicary et al. [68] reported mixed findings on cigarette use and alcohol consumption over the assessment time points in the two intervention groups. Similarly, measurements of skills related to substance abuse (decision making skills, refusal skills, media awareness and resistance skills) resulted in mixed findings.

A multi-health domain intervention which targeted PA, dietary habits, substance abuse and mental health [59] resulted in significantly improved cardiovascular health knowledge scores in males and females. In females, dietary habits, total cholesterol and estimated VO2max also significantly improved. All other risk factors were non-significant in males and females. A sleep intervention qualitatively assessed the acceptability of two mobile phone apps to improve sleep hygiene [57]. The overall feedback on the application was positive, although several barriers were identified, and the students were sceptical about successfully adopting sleep hygiene practices. Furthermore, an intervention targeting both mental health and sleep significantly improved some psychological functioning measures (anxiety, negative coping approaches and self-reported anger) but not cortisol levels or sleep scores [63]. An intervention targeting mental health and PA, which used qualitive analysis to understand the perceived impact of the intervention on youth participants, found that the program was a promising method to improve psychological, social and physical well-being [87]. The adolescents, parents and program implementers described benefits across seven main areas, including dancing and related skills, behaviours (e.g., reduced television viewing), physical well-being, psychological well-being, relationships, respect for others and for diversity, and school performance. A PA, diet and mental health intervention assessed predictors to dropout in the ‘Mexa Se’ intervention [79]. It was reported that in the intervention group, age, body mass, height and BMI were all significant predictors of drop out. Finally, in the intervention implemented by Kerr et al. [52], aimed at improving PA, diet and substance abuse, it was reported that general health knowledge scores increased significantly more in the intervention group compared to the control. Health behaviours, however, did not significantly differ between groups post-intervention.

3.6. Effective Intervention Strategies

3.6.1. ‘Hands-On’ or Practical Learning

Of the interventions identified within this review, many adopted ‘hands-on’ or practical learning components, a strategy that proved effective across various health domains. For example, an intervention targeting social, emotional and academic function by Mendelson et al. [53] incorporated mindfulness sessions into the program; resulting in significant improvements across all three health scores (social, emotional and academic function) post-intervention. Similarly, participants in an intervention by Sibinga et al. [63], who practiced mindfulness and yoga within the intervention, reported significantly improved psychological functioning. Furthermore, in an intervention targeting dietary habits [54], participants prepared and ate minimally processed meals with the objective of making these foods look ‘cool and fun’. The intervention resulted in a large significant increase in the participant’s consumption of minimally processed foods. Another example of practical learning was articulated in Jackson et al. [69], where the students learned pertinent nutrition and PA information that was later incorporated into writing and performing their own “healthy” skits in a theatre-based program. This intervention resulted in improved knowledge around PA and dietary habits, improved health-related choices, and the students reported that the intervention was an enjoyable experience.

3.6.2. Peer Support

The use of peer support was another effective intervention strategy identified within this review. For example, a social marketing intervention by Aceves-Martins et al. [63], which aimed to encourage adolescents to increase their fruit and vegetable intake, PA levels and reduce screen time, was led and designed by peer students (who were trained by university specialists). The social marketing intervention resulted in a significant increase in fruit intake, PA levels and a reduction in screen time. Similarly, two interventions [64,66], also targeting dietary habits and PA levels, which used the Transtheoretical Model to tailor intervention strategies and feedback suggestions to adolescents, also adopted a peer-led approach. Participants in the preparation, action and maintenance stages of change were used as peer models for students in the pre-contemplation and contemplation stages of change and led interventions sessions targeting healthy eating and exercise promotion with the assistance of nursing students. Both interventions produced findings supporting the peer-led approach, with one intervention reporting significant changes in dietary behaviour and PA in the intervention group compared to the control [66], and the other reporting non-significant changes in dietary habits and significant changes in PA levels in the intervention group compared to the control [64].

3.6.3. Holistic Approaches

Finally, this review identified the use of holistic approaches to school-based health interventions as an effective strategy. It has been suggested that for health interventions to be effective, they should focus on more than just the educational component [88], with research stating that interventions should also target the school environment and engagement with families or communities (or both) [34]. The benefit of adopting an intervention framework which targets all three areas is demonstrated by Hollis et al. [75]. The intervention, which incorporated teaching strategies to maximise PA and PE lessons (formal health curriculum), the development of school policies and PA lunch programs (school environment), and the development of a community PA expo and community newsletters (community links), reported significant improvements in weight, BMI and PA [89] (these effects were reported in a paper outside of this review). Although no other interventions included in this review met all three of the criteria of the WHO HPS framework as comprehensively as Hollis et al. [75], other interventions which targeted either the community/parent links, or the school environment also reported successful findings. For example, the intervention presented in Casey at al. [74], which was shown to significantly improve health-related quality of life, implemented a PE component that was linked to a community component addressing previously reported barriers to PA participation. Furthermore, the pedagogical approach of the PE program in this study [74] aligned with recent developments in the community sports club. Additionally, a park-based program targeting social emotional learning by engaging the parents through family sessions (supplementing the youth’s sessions) developed specific strategies that the families could model and reinforce at home [56], ultimately leading to significant improvements in the staff reported measures of problem behaviours and social skills in the adolescent’s cohort. Similarly, an intervention by Jackson et al. [69], which was successful in improving PA and dietary knowledge and behaviours (although no significance was reported), involved the parents by hosting healthy eating recipe sessions, completing home-based intervention sessions and inviting the parents to a performance by the adolescents where pertinent dietary or PA information was translated into a theatrical performance. Finally, an intervention by Alaimo et al. [62] involved the assembly of a ‘Coordinated School Health Team’ (CSHT) to improve school nutrition and practices and policies. The CSHT, which was made up of representatives from various sectors of the school (including students), met to discuss school nutrition policies, nutrition environment, health education programs and school food service programs. Intervention schools adopted significantly more nutrition policies and practices than schools in the control group. In addition, students from the intervention schools consumed significantly more fruit and fibre, and less cholesterol than students from the control schools.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to review the evidence for school-based interventions aimed at HL-related areas in socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents and to identify effective intervention strategies for this population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to review this topic which is not restricted to a specific region of the world. The evidence collected gives insight into the interventions carried out, and in particular, the success of various strategies implemented with this population, which can be used to guide future intervention development.

Forty-one intervention studies were identified, with the majority carried out in the US. This review aimed to identify studies targeting five health domains (PA, diet, mental health, substance abuse and sleep). The majority of interventions targeted PA, diet and mental health, while very few focused on substance abuse and even less on sleep. This is despite the well-known harmful impacts of substance abuse and poor sleeping habits on adolescent’s health and well-being [90,91,92], and the evidence supporting the benefits of behavioural interventions in improving sleeping habits [93] and substance abuse [92] in youth. Thus, future studies are needed to assess whether interventions targeting sleep and substance abuse are effective in socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents.

The identified interventions varied greatly in research designs, aims, components, outcome measures and effects, increasing the difficulty to compare and analyse effectiveness per health domain, or across health domains. In addition, although highly recommended [94], only seventeen of the included interventions measured fidelity. This adds to the difficulty of comparing the quality or effectiveness of an intervention, as implementation fidelity of certain intervention strategies within and between studies may have varied greatly. Future studies should include fidelity or process evaluation evidence to allow for a better understanding of the implementation process and to determine whether disappointing results may have been related to poor program delivery [95]. Furthermore, there was a high variance in the risk of bias scores obtained, with numerous interventions scoring as ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear’ on multiple aspects of their study designs, adding to the difficulty of interpreting intervention outcomes. Nevertheless, numerous successful intervention strategies were identified. These include ‘hands-on’ or practical learning, peer support and adopting a holistic intervention approach.

4.1. Effective Intervention Strategies

The successful implementation of ‘hands-on’ or practical learning intervention strategies in the studies identified within this review [53,54,63] aligns with previous research that states educational activities which are carried out through interactive tasks and are focused on context specific learning, may improve health-related decision making and motivate adolescents’ to improve behaviour [24,96]. An example of this is ‘LifeLab’ in Southampton; an innovative ‘hands-on’ science-based approach targeting adolescents’ HL through scientific knowledge and lifestyle behaviours [97].

Interventions identified in this review have demonstrated the effectiveness of peer support in adolescent health interventions [63,64,66]. During adolescence, peer relationships begin to develop, and these relationships are reported to have positive or negative influences on health [98]. Connections with supportive and prosocial peers can lead to healthier behaviours and reduced likelihood of risky behaviours [99]. In addition, peer modelling and awareness of peer norms can be protective against behaviours such as sexual risk [100] and substance abuse [101]. The findings from this review have further underlined the benefits of peer support by using adolescent peers to design and deliver intervention components [63,64,66].

This review has provided further evidence for the benefits of adopting a holistic approach to school-based health interventions, rather than just targeting on the curriculum element. The WHO HPS framework suggests that school-based interventions should adopt an eco-holistic approach by targeting three key areas—the formal health curriculum, the school environment, and engagement with families or communities (or both) [34]. While most of the interventions within this review targeted the formal school curriculum dimension of the framework, less were concerned with targeting all three critical elements. The benefit of adopting an intervention framework which targets all three areas is demonstrated by Hollis et al. [75]. Although only one intervention was successful in incorporating all components of the HPS framework [34], others which have targeted critical elements, such as parent or community engagement or the school environment [56,62,69,74], appear to foster positive improvements in the health and well-being of low socioeconomic adolescents.

4.2. Implications of the Identified Interventions Strategies for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Adolescents

As previously mentioned, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations tend to benefit less from health interventions than those from more affluent backgrounds, often resulting in greater health disparities [40]. Yet, to date, there has been limited evidence to inform the design of health interventions for this population [102]. This review, therefore, has attempted to add to the evidence base by identifying effective and attractive intervention strategies which have been shown to work specifically in this socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescent cohort.

Intervention strategies that involve students carrying out practical activities appear to be more effective than those involving didactic learning. This has been reported elsewhere in lifestyle behavioural interventions targeting adolescents from socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, where students have reported enjoying ‘getting away’ rather than learning from the classroom [103]. In addition, providing such ‘hands-on’ activities which are financially inexpensive is crucial when designing intervention strategies for this population, as cost has been reported as being a considerable barrier for participation [70]. The strategies implemented in successful interventions included in this review, such as mindfulness activities [53], yoga [83] and performing “healthy” skits [53], are very cost effective and are therefore suitable options.

Peer learning, in which peers design or deliver (or both) the intervention, appears to be an effective strategy in this cohort. This approach is said to give the students a sense of leadership and empower them to change their lifestyle [104]. Furthermore, including the adolescents in the design and implementation of the intervention is crucial, particularly in a socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, as it ensures the voice of the student is central to the design, which in turn maximises the potential for the intervention to meet the preferences and needs of the population [105]. The WHO strongly advocates the inclusion of peers in the design and implementation of health interventions in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, as they are trusted by the participants, it leads to greater acceptability and it provides the adolescents with a sense of ownership [106].

Adopting interventions that consist of more than just a school-based educational element appears to be critical in socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. In particular, involving a parents in the intervention as a strategy is important, as parents play a vital role in the lifestyle behaviours of their children [107]. In addition, reaching a range of settings in which youth spend most of their time increases the likelihood of long-term intervention effects [108]. In a review study, the importance of engaging the parents of socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents in lifestyle behaviour interventions has been highlighted [109], with another study, which failed to change dietary behaviours, stating that the adolescents felt that this was due to a lack of support from their parents [103]. Furthermore, adolescents who perceive their parents to be leading a healthy lifestyle are more likely to also partake in healthy behaviours [110]. Fostering this sort of modelling and parental support through engaging parents in school-based health interventions appears to be a viable solution to improve the impact of interventions in this population.

4.3. The Intervention Strategies and Health Literacy

If HL is understood as an observable set of skills, intervention efforts should focus on improving an individual’s skills and capacities [111]. Despite this, previous reviews have indicated that existing HL research has been driven by health concerns, which potentially underplays the development of educational outcomes, such as critical thinking, the development of capabilities and motivation for behaviour change [34,112]. Nevertheless, the current review identifies a number of intervention strategies potentially useful for influencing HL. The classifications of HL provided by Nutbeam (2000) may be a useful way to interpret the strategies identified in the current review [113]. Considering interactive HL, the ability to extract health information, apply new information in changing circumstances and engage with others to make decisions, strategies that include practical learning activities and interaction with peers may be of particular use. Many studies included providing the opportunity for shared decision making as part of the intervention [80,81,82]. Knapp et al. [60] held interactive classes outside of the classroom (in the kitchen and garden). Vicary et al. [68] used a life skills training programme to improve the adolescent’s confidence and capabilities, specifically targeting decision making skills, refusal skills, media awareness and resistance skills in relation to substance abuse. Including the social support network in an intervention may also be of benefit to increase motivation to change behaviour [56,62,74]. Strategies relating to critical HL, the ability to critically analyse information from a wide range of sources, were less prevalent. Only one study [78] attempted to target critical HL by incorporating discussions around a critical approach to the use of supplements in PA. However, many studies used pedagogical techniques and educational resources that could be structured around developing critical HL. For example, discussions [56,59], problem solving [82], role play [52,56], provision of resources [76,78,80], and the development of resilience [72] were all used when targeting health behaviour change. Such components could be easily delivered through practical activities or involve peer interaction to enhance learning. The use of smaller sessions, with groups of similar individuals, to target consciousness raising and self-re-evaluation, with regular feedback could be offered to improve basic functional HL behaviours, which enables individuals to function effectively in everyday situations, as this can improve the motivation and maintenance of behaviour change [66]. Other strategies to consider to improve HL in school aged children may be teacher training [75,76], as existing HL research has suggested pedagogical guidance will be needed to deliver HL informed curricula [14,18,112,114,115], and the holistic approach (previously outlined in this review), which may be a way to incorporate HL as part of the wider HPS framework [14,34,56,62,69,74,75].

It should also be acknowledged that strategies that lead to health behaviour change may or may not lead to improvements in HL and vice versa. One such example of this may be that even in a person considered to have high level of observable HL skills, they may experience real challenges in applying those skills in an unfamiliar environment [111]. This should be considered when interpreting the findings of the current study, which found that none of the included interventions explicitly targeted HL, nor did any use HL as an outcome measure. Despite this, as indicated earlier, strategies may be useful and transfer across HL, health promotion and health behaviours, and future research exploring the transferability of these skills, and the relationship between these connected fields is warranted. A factor to consider in the dearth of school-based HL interventions aimed at socioeconomically disadvantaged populations may be the lack of an appropriate tool to measure HL in this context, with interventions to date using adult-adapted HL tools which some have argued to be inaccurate [116]. As a result, it may have been problematic to place HL as a primary outcome of an intervention. Recently, a tool has been developed specifically for use in adolescent populations, but its applicability is yet to be tested [117]. Furthermore, another HL measurement tool is currently in development, which is following a rigorous co-design process with young people to understand the context and needs of adolescent [118]. The development of valid and sensitive measurement tools can be utilised to guide intervention designs to target the specific needs of a particular population and allow for the potential effects to be easily and accurately tracked.

4.4. Applying Effective Intervention Strategies

As adolescents encounter unique health issues based on their level of puberty, development, social environment and social context [22], caution should be exercised when using previous interventions to inform future approaches. ‘Ready-made’ or ‘one-size-fits-all’ health promotion approaches have become increasingly popular [119], yet evidence suggests that interventions developed outside of the targeted schools are rarely meaningful or effective [120]. For health interventions, and in particular HL interventions, to ensure that the health needs and priorities are met, it is recommended that they should be co-produced with all relevant stakeholders [115]. This approach values the knowledge and input of key personnel to facilitate deeper engagement in intervention content, and to ensure that interventions are contextual, sustainable, and equity driven; all of which have been demonstrated in previous HL intervention development approaches [121,122]. Based on this, effective intervention strategies identified within this review can be used to guide the development of future interventions but should always be contextualised and tailored to suit the targeted population.

5. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically review school-based HL-related interventions in socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents. The study provides evidence on interventions carried out globally and was not aimed at a specific region of the world. It must be noted that due to the contentiousness of defining socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, studies which self-identified as socioeconomically disadvantaged (or the equivalent) were included. It is acknowledged that included studies would have used different methods to define socioeconomically disadvantaged populations and, therefore, this may be a limitation when comparing results of studies within this review. The current review used a standardised and well-established appraisal tool for the assessment of study quality to enable comparison between studies. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool, however, was originally intended to appraise RCTs [46] and many of the studies included in this review scored poorly or did not report information related to certain aspects of study bias. As a result, the variation between study quality indicates that caution should be exercised when interpreting the results of intervention effects. Due to the large volume of peer-reviewed publications identified and screened in this review, and the practicalities of running and managing this review, the authors did not include a grey literature search. It is acknowledged that by excluding non-published articles, there is an increased risk of publication bias and the possibility of missing out on additional information that a grey literature search may have provided. This review included interventions reporting on outcome and process evaluation, yet many interventions did not report on the process evaluation or intervention fidelity. Future research should consider comprehensively reporting intervention evaluation to provide a deeper insight into the intervention delivery.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review provides evidence on the interventions implemented which aimed to improve HL-related areas in socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents. This review highlights the lack of interventions targeting sleeping habits and substance abuse in this demographic. In addition, no interventions have explicitly aimed to improve HL. Nevertheless, successful interventions strategies were identified that could be used to inform future intervention development. These include the integration of practical-based learning activities and the use of peer educators. Furthermore, evidence supported linking the intervention to the parents and local community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, C.S., H.R.G., J.I. and S.B.; methodology, C.S., H.R.G., J.I. and S.B.; validation, C.S., H.R.G., J.I. and S.B.; investigation, C.S. and H.R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, H.R.G., J.I. and S.B.; visualisation, C.S.; supervision, S.B. and J.I.; project administration S.B. and J.I.; funding acquisition, C.S and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Irish Heart Foundation and the Irish Research Council under the Irish Research Council’s Enterprise Partnership Scheme, Project ID: EPSPG/2020/489. The APC was funded by the Irish Research Council’s Enterprise Partnership Scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author team would like to thank colleagues in the Irish Heart Foundation (Janis Morrissey and Laura Hickey) and University College Dublin (Dr Celine Murrin and Dr Ailbhe Spillane) who contributed to the refinement of the final search criteria used in this review, as part of a working group on a larger Irish Heart Foundation Schools Health Literacy Demonstration project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. PICO Table

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adolescents with a reported mean age between 12 and 16 years from a socioeconomically disadvantaged (or equivalent) background. | Mean age not between 12 and 16 or special populations (e.g., children with learning difficulties, pregnant adolescents, exclusively obese individuals, or those with a specific health condition). |

| Intervention | The implementation of an intervention related to health literacy (increases health knowledge, understanding, awareness, motivation, confidence) in at least one of the following areas physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary habits, sleeping habits, mental health or substance abuse. | The intervention did not include an educational element or a component targeting health literacy (increases health knowledge, understanding, awareness, motivation, confidence). |

| Context | School-based interventions, interventions that could be feasibly implemented in a school setting, or interventions that could be linked to a school curriculum. | Book chapters, case studies, student dissertations, conference abstracts, review articles, meta-analyses, editorials, protocol papers or systematic reviews. |

| Outcome | Aimed to increase health knowledge/comprehension, understanding, behaviour, value, well-being, motivation, self-efficacy or self-monitoring in relation any of the following domains: physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary habits, sleeping habits, mental health or substance abuse. | Outside of the targeted health domains. |

| Study Design | Published in English and in a peer-reviewed journal. | Systematic review, meta-analysis or full text not available. |

Appendix B. Search Strategy (For PubMed)

((((health[Title/Abstract] OR “health literacy”[Title/Abstract] OR “health knowledge”[Title/Abstract] OR “health competenc*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health understanding”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“physical activity”[Title/Abstract] OR exercis*[Title/Abstract] OR sedentary[Title/Abstract] OR inactiv*[Title/Abstract] OR “substance abuse”[Title/Abstract] OR smok*[Title/Abstract] OR vaping[Title/Abstract] OR vape*[Title/Abstract] OR “e-cigarette*”[Title/Abstract] OR cigarette*[Title/Abstract] OR tobacco[Title/Abstract] OR drug*[Title/Abstract] OR alcohol*[Title/Abstract] OR “mental health”[Title/Abstract] OR “emotional health”[Title/Abstract] OR “psychological health”[Title/Abstract] OR wellbeing[Title/Abstract] OR “well-being”[Title/Abstract] OR diet*[Title/Abstract] OR “health* food*”[Title/Abstract] OR food*[Title/Abstract] OR nutrition*[Title/Abstract] OR “eating behav*”[Title/Abstract] OR sleep*[Title/Abstract])) AND (intervention*[Title/Abstract] OR change[Title/Abstract] OR program*[Title/Abstract] OR behav*[Title/Abstract] OR lifestyle[Title/Abstract] OR education*[Title/Abstract] OR “health promotion*”[Title/Abstract] OR effect*[Title/Abstract])) AND (youth[Title/Abstract] OR adolescen*[Title/Abstract] OR teen*[Title/Abstract] OR pupil*[Title/Abstract] OR student*[Title/Abstract] OR “young people*”[Title/Abstract])) AND (poverty[Title/Abstract] OR “low income”[Title/Abstract] OR “low-income”[Title/Abstract] OR “economic factor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “social inequali*”[Title/Abstract] OR socioeconomic*[Title/Abstract] OR “social economic*”[Title/Abstract] OR “social-economic*”[Title/Abstract] OR “social class”[Title/Abstract] OR “welfare assist*”[Title/Abstract] OR “social assist*”[Title/Abstract] OR subsidi*[Title/Abstract] OR “economic burden”[Title/Abstract] OR unemploy*[Title/Abstract] OR disenfranchi*[Title/Abstract] OR impoverished[Title/Abstract] OR penniless[Title/Abstract] OR “financially disadvantaged”[Title/Abstract] OR “financially distressed”[Title/Abstract] OR “economically disadvantaged”[Title/Abstract] OR “socially disadvantaged”[Title/Abstract] OR “health literacy”[Title/Abstract] OR “health proficien*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health inequalit*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health equit*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health qualit*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health inequit*”[Title/Abstract] OR “health disparit*”[Title/Abstract])

References

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Naghavi, M.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattu, V.K.; Sakhamuri, S.M.; Kumar, R.; Spence, D.W.; Bahammam, A.S.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Insufficient Sleep Syndrome: Is it time to classify it as a major noncommunicable disease? Sleep Sci. 2018, 11, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, V.K.; Rubinstein, A.; Ganju, V.; Kanellis, P.; Loza, N.; Rabadan-Diehl, C.; Daar, A.S. Grand Challenges: Integrating Mental Health Care into the Non-Communicable Disease Agenda. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D. Measuring the Global Burden of Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarborough, P.; Bhatnagar, P.; Wickramasinghe, K.K.; Allender, S.; Foster, C.; Rayner, M. The economic burden of ill health due to diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol and obesity in the UK: An update to 2006-07 NHS costs. J. Public Heal. 2011, 33, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C.; Krueger, P.M.; Denney, J.T. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.J.; Kinra, S.; Casas, J.P.; Smith, G.D.; Ebrahim, S. Non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: Context, determinants and health policy. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2008, 13, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, E.R.; Dombrowski, S.U.; McCleary, N.; Johnston, M. Are interventions for low-income groups effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health Promotion Glossary. Heal. Promot. Int. 1998, 13, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D.; McGill, B.; Premkumar, P. Improving health literacy in community populations: A review of progress. Heal. Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterham, R.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R. Health literacy: Applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public Heal. 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Heal. Promot. Int. 2017, 32, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröder, J.; Chang, P.; Kickbusch, I.; Levin-Zamir, D.; McElhinney, E.; Nutbeam, D.; Okan, O.; Osborne, R.; Pelikan, J.; Rootman, I.; et al. IUHPE Position Statement on Health Literacy: A practical vision for a health literate world. Glob. Heal. Promot. 2018, 25, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleary, S.A.; Joseph, P.; Pappagianopoulos, J.E. Adolescent health literacy and health behaviors: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 62, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paakkari, L.; Kokko, S.; Villberg, J.; Paakkari, O.; Tynjälä, J. Health literacy and participation in sports club activities among adolescents. Scand. J. Public Heal. 2017, 45, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paakkari, L.; Torppa, M.; Mazur, J.; Boberova, Z.; Sudeck, G.; Kalman, M.; Paakkari, O. A Comparative Study on Adolescents’ Health Literacy in Europe: Findings from the HBSC Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.T.; Torppa, M.P.; Paakkari, O.-P.; Välimaa, R.S.; A Ojala, K.S.; A Tynjälä, J. Does health literacy explain the link between structural stratifiers and adolescent health? Eur. J. Public Heal. 2019, 29, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormacq, C.; Broucke, S.V.D.; Wosinski, J. Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Heal. Promot. Int. 2019, 34, e1–e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Health 2020 A European Policy Framework and Strategy for the 21st Century. 2013. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S.M.; A Afifi, R.; Bearinger, L.H.; Blakemore, S.-J.; Dick, B.; Ezeh, A.C.; Patton, G.C. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods-Townsend, K.; Leat, H.; Bay, J.; Bagust, L.; Davey, H.; Lovelock, D.; Christodoulou, A.; Griffiths, J.; Grace, M.; Godfrey, K.; et al. LifeLab Southampton: A programme to engage adolescents with DOHaD concepts as a tool for increasing health literacy in teenagers –a pilot cluster-randomized control trial. J. Dev. Orig. Heal. Dis. 2018, 9, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J.; Cooper, C.; Margetts, B.M.; Barker, M.; Inskip, H.M. Changing health behaviour of young women from disadvantaged backgrounds: Evidence from systematic reviews. In Proceedings of the Nutrition Society; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 68, pp. 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Borzekowski, D.L. Considering Children and Health Literacy: A Theoretical Approach. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S282–S288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Getting evidence into policy and practice to address health inequalities. Heal. Promot. Int. 2004, 19, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay, J.L.; Vickers, M.H.; Mora, H.A.; Sloboda, D.M.; Morton, S.M. Adolescents as agents of healthful change through scientific literacy development: A school-university partnership program in New Zealand. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2017, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.-C.; Nutbeam, D.; Aldinger, C.; Leger, L.S.; Bundy, D.; Hoffmann, A.M.; Yankah, E.; McCall, D.; Buijs, G.; Arnaout, S.; et al. Schools for health, education and development: A call for action. Heal. Promot. Int. 2008, 24, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, M.L.; Chilton, R.; Wyatt, K.; Abraham, C.; Ford, T.; Woods, H.B.; Anderson, R.H. Implementing health promotion programmes in schools: A realist systematic review of research and experience in the United Kingdom. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonell, C.; Humphrey, N.; Fletcher, A.; Moore, L.; Anderson, R.; Campbell, R. Why schools should promote students’ health and wellbeing. BMJ 2014, 348, g3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.J.; Greene, A.C. Do Health and Education Agencies in the United States Share Responsibility for Academic Achievement and Health? A Review of 25 Years of Evidence About the Relationship of Adolescents’ Academic Achievement and Health Behaviors. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2013, 52, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suhrcke, M. The impact of health and health behaviours on educati onal outcomes in high-income countries: A review of the evidence. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, R.; Bonnell, C.P.; E Jones, H.; Pouliou, T.; Murphy, S.M.; Waters, E.; A Komro, K.; Gibbs, L.F.; Magnus, D.; Campbell, R. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD008958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khambalia, A.Z.; Dickinson, S.; Hardy, L.L.; Gill, T.; Baur, L.A. A synthesis of existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of school-based behavioural interventions for controlling and preventing obesity. Obes. Rev. 2011, 13, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, E.; De Silva-Sanigorski, A.; Burford, B.J.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J.; Gao, Y.; Armstrong, R.; Prosser, L.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J.; Zeveloff, A.; Steckler, A.; Schneider, M.; Thompson, D.; Pham, T.; Volpe, S.L.; Hindes, K.; Sleigh, A.; McMurray, R.G.; et al. Process evaluation results from the HEALTHY physical education intervention. Heal. Educ. Res. 2011, 27, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.; Elmer, S.; Thomas, K.; Osborne, R.; MacIntyre, K.; Shelley, B.; Murray, L.; Harpur, S.; Webb, D. HealthLit4Kids study protocol; crossing boundaries for positive health literacy outcomes. BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupe, N.; Cotterill, S.; Peters, S. Tailoring lifestyle interventions to low socio-economic populations: A qualitative study. BMC Public Heal. 2018, 18, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, R.; Judge, K.; Bauld, L. Social inequalities in quitting smoking: What factors mediate the relationship between socioeconomic position and smoking cessation? J. Public Heal. 2010, 33, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, D.; Frosini, F. Clustering of unhealthy behaviours over time: Implications for policy and practice. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Adams, J.; Heywood, P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? Soc. Inequal. Public Health 2009, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockene, I.S.; Tellez, T.L.; Rosal, M.C.; Reed, G.W.; Mordes, J.P.; Merriam, P.A.; Olendzki, B.C.; Handelman, G.; Nicolosi, R.J.; Ma, Y. Outcomes of a Latino Community-Based Intervention for the Prevention of Diabetes: The Lawrence Latino Diabetes Prevention Project. Am. J. Public Heal. 2012, 102, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Michie, S.; A Geraghty, A.W.; Yardley, L.; Gardner, B.; Shahab, L.; A Stapleton, J.; West, R. Internet-based intervention for smoking cessation (StopAdvisor) in people with low and high socioeconomic status: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, K.A.; Robbins, L.B.; Ling, J.; Sharma, D.B.; Dalimonte-Merckling, D.M.; Voskuil, V.R.; Kaciroti, N.; Resnicow, K. Effects of the Girls on the Move randomized trial on adiposity and aerobic performance (secondary outcomes) in low-income adolescent girls. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, L.B.; Ling, J.; Toruner, E.K.; Bourne, K.A.; Pfeiffer, K.A. Examining reach, dose, and fidelity of the “Girls on the Move” after-school physical activity club: A process evaluation. BMC Public Heal. 2016, 16, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.D.; Gilley, J.; James, J.; Kimani, M. “High Five to Healthy Living”: A Health Intervention Program for Youth at an Inner City Community Center. J. Community Heal. 2011, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, W.L. Reducing Substance Use Among African American Adolescents: Effectiveness of School-Based Health Centers. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pr. 2003, 10, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J.L.; Burnette, J.L.; Widman, L.; Hoyt, C.; Prinstein, M.J. Randomized Trial of a Single-Session Growth Mind-Set Intervention for Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.C.; Valois, R.F.; Farber, N.B.; Vanable, P.A.; DiClemente, R.J.; Salazar, L.; Brown, L.K.; Carey, M.P.; Romer, D.; Stanton, B.; et al. Effects of Promoting Health Among Teens on Dietary, Physical Activity, and Substance Use Knowledge and Behaviors for African American Adolescents. Am. J. Heal. Educ. 2013, 44, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mendelson, T.; Tandon, S.D.; Obrennan, L.M.; Leaf, P.J.; Ialongo, N.S. Brief report: Moving prevention into schools: The impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. J. Adolesc. 2015, 43, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luesse, H.B.; Luesse, J.E.; Lawson, J.; Koch, P.A.; Contento, I.R. In Defense of Food Curriculum: A Mixed Methods Outcome Evaluation in Afterschool. Heal. Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issner, J.H.; Mucka, L.E.; Barnett, D. Increasing Positive Health Behaviors in Adolescents with Nutritional Goals and Exercise. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 26, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, S.L.; Dinizulu, S.M.; Rusch, D.; Boustani, M.M.; Mehta, T.G.; Reitz, K. Building Resilience After School for Early Adolescents in Urban Poverty: Open Trial of Leaders @ Play. Adm. Policy Ment. Heal. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2014, 42, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quante, M.; Khandpur, N.; Kontos, E.Z.; Bakker, J.P.; Owens, J.A.; Redline, S. A Qualitative Assessment of the Acceptability of Smartphone Applications for Improving Sleep Behaviors in Low-Income and Minority Adolescents. Behav. Sleep Med. 2019, 17, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, S.E.; Gill, M.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Rice, L.N.; Crespi, C.M.; Koniak-Griffin, D.; Prelip, M.L. The Effects of a 2-Year Middle School Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Its Determinants. J. Phys. Act. Heal. 2019, 16, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardy, P.S.; White, R.E.; Haltiwanger-Schmitz, K.; Magel, J.R.; McDermott, K.J.; Clark, L.T.; Hurster, M.M. Coronary disease risk factor reduction and behavior modification in minority adolescents: The PATH program. J. Adolesc. Heal. 1996, 18, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, M.B.; Hall, M.T.; Mundorf, A.R.; Partridge, K.L.; Johnson, C.C. Perceptions of School-Based Kitchen Garden Programs in Low-Income, African American Communities. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2018, 20, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.J. A Pilot Test of the Latin Active Hip Hop Intervention to Increase Physical Activity among Low-Income Mexican-American Adolescents. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2012, 26, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaimo, K.; Oleksyk, S.; Golzynski, D.; Drzal, N.; Lucarelli, J.; Reznar, M.; Wen, Y.; Yoder, K.K. The Michigan Healthy School Action Tools Process Generates Improvements in School Nutrition Policies and Practices, and Student Dietary Intake. Heal. Promot. Pr. 2015, 16, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibinga, E.M.; Perry-Parrish, C.; Chung, S.-E.; Johnson, S.B.; Smith, M.; Ellen, J.M. School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: A small randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenn, M.; Malin, S.; Bansal, N.; Delgado, M.; Greer, Y.; Havice, M.; Ho, M.; Schweizer, H. Addressing Health Disparities in Middle School Students’ Nutrition and Exercise. J. Community Heal. Nurs. 2003, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenn, M.; Malin, S.; Brown, R.L.; Greer, Y.; Fox, J.; Greer, J.; Smyczek, S. Changing the tide: An Internet/video exercise and low-fat diet intervention with middle-school students. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2005, 18, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenn, M.; Malin, S.; Bansal, N.K. Stage-based interventions for low-fat diet with middle school students. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2003, 18, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, M.M.; Hager, E.R.; Le, K.; Anliker, J.; Arteaga, S.S.; DiClemente, C.; Gittelsohn, J.; Magder, L.; Papas, M.; Snitker, S.; et al. Challenge! Health Promotion/Obesity Prevention Mentorship Model Among Urban, Black Adolescents. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicary, J.R.; Henry, K.L.; Bechtel, L.J.; Swisher, J.D.; Smith, E.A.; Wylie, R.; Hopkins, A.M. Life Skills Training Effects for High and Low Risk Rural Junior High School Females. J. Prim. Prev. 2004, 25, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.J.; Mullis, R.M.; Hughes, M. Development of a theater-based nutrition and physical activity intervention for low-income, urban, African American adolescents. Prog. Community Heal. Partnerships: Res. Educ. Action 2010, 4, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, D.L.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Okely, A.D.; Collins, C.E.; Batterham, M.; Callister, R.; Lubans, D.R. The Nutrition and Enjoyable Activity for Teen Girls Study: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Okely, A.D.; Dewar, D.; Collins, C.E.; Batterham, M.; Callister, R.; Plotnikoff, R.C. Preventing Obesity Among Adolescent Girls. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dray, J.; Bowman, J.; Campbell, E.; Freund, M.; Hodder, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Richards, J.; Leane, C.; Green, S.; Lecathelinais, C.; et al. Effectiveness of a pragmatic school-based universal intervention targeting student resilience protective factors in reducing mental health problems in adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2017, 57, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Morgan, P.J.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Stodden, D.F.; Lubans, D.R. Mediating effects of resistance training skill competency on health-related fitness and physical activity: The ATLAS cluster randomised controlled trial. J. Sports Sci. 2015, 34, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, M.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Telford, A.; Eime, R.M.; Mooney, A.; Payne, W.R. Effectiveness of a school-community linked program on physical activity levels and health-related quality of life for adolescent girls. BMC Public Heal. 2014, 14, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, J.L.; Sutherland, R.; Campbell, L.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Nathan, N.; Wolfenden, L.; Okely, A.D.; Davies, L.; Williams, A.; et al. Effects of a ‘school-based’ physical activity intervention on adiposity in adolescents from economically disadvantaged communities: Secondary outcomes of the ‘Physical Activity 4 Everyone’ RCT. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandeira, A.D.S.; Silva, K.S.; Bastos, J.L.D.; Silva, D.A.S.; Lopes, A.D.S.; Filho, V.C.B. Psychosocial mediators of screen time reduction after an intervention for students from schools in vulnerable areas: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leme, A.C.B.; Baranowski, T.; Thompson, D.; Nicklas, T.; Philippi, S.T. Sustained impact of the “Healthy Habits, Healthy Girls – Brazil” school-based randomized controlled trial for adolescents living in low-income communities. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, K.B.B.; Fiaccone, R.L.; Couto, R.D.; Ribeiro-Silva, R.D.C. Evaluation of the effects of a programme promoting adequate and healthy eating on adolescent health markers: An interventional study. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 1582–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Berria, J.; Minatto, G.; A Lima, L.R.; Martins, C.R.; Petroski, E.L. Predictors of dropout in the school-based multi-component intervention, ‘Mexa-se’. Heal. Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröberg, A.; Jonsson, L.; Berg, C.; Lindgren, E.-C.; Korp, P.; Lindwall, M.; Raustorp, A.; Larsson, C. Effects of an Empowerment-Based Health-Promotion School Intervention on Physical Activity and Sedentary Time among Adolescents in a Multicultural Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, C.; Larsson, C.; Korp, P.; Lindgren, E.-C.; Jonsson, L.; Fröberg, A.; E Chaplin, J.; Berg, C. Empowering aspects for healthy food and physical activity habits: Adolescents’ experiences of a school-based intervention in a disadvantaged urban community. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Heal. Well-being 2018, 13, 1487759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.; A Weiss, H.; Varghese, B.; Khandeparkar, P.; Pereira, B.; Sharma, A.; Gupta, R.; A Ross, D.; Patton, G.; Patel, V. Promoting school climate and health outcomes with the SEHER multi-component secondary school intervention in Bihar, India: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganpat, T.S.; Sethi, J.K.; Nagendra, H.R. Yoga improves attention and self-esteem in underprivileged girl student. J. Educ. Heal. Promot. 2013, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuy, V.; De Cocker, K.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Maes, L.; Seghers, J.; Lefevre, J.; De Martelaer, K.; Brooke, H.; Cardon, G. Evaluation of a real world intervention using professional football players to promote a healthy diet and physical activity in children and adolescents from a lower socio-economic background: A controlled pretest-posttest design. BMC Public Heal. 2014, 14, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Araya, R.; Fritsch, R.; Spears, M.; Rojas, G.; Martinez, V.; Barroilhet, S.; Vöhringer, P.; Gunnell, D.; Stallard, P.; Guajardo, V.; et al. School Intervention to Improve Mental Health of Students in Santiago, Chile. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves-Martins, M.; Llauradó, E.; Tarro, L.; Moriña, D.; Papell-Garcia, I.; Prades-Tena, J.; Kettner-Høeberg, H.; Puiggròs, F.; Arola, L.; Davies, A.; et al. A School-Based, Peer-Led, Social Marketing Intervention To Engage Spanish Adolescents in a Healthy Lifestyle (“We Are Cool”—Som la Pera Study): A Parallel-Cluster Randomized Controlled Study. Child. Obes. 2017, 13, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulac, J.; Kristjansson, E.; Calhoun, M. ‘Bigger than hip-hop?’ Impact of a community-based physical activity program on youth living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in Canada. J. Youth Stud. 2011, 14, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, N.; Jamal, F.; Viner, R.M.; Dickson, K.; Patton, G.; Bonell, C. School-Based Interventions Going Beyond Health Education to Promote Adolescent Health: Systematic Review of Reviews. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2016, 58, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.L.; Campbell, E.M.; Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Nathan, N.K.; Wolfenden, L.; Okely, A.D.; Gillham, K.E.; Hollis, J.L.; Oldmeadow, C.J.; et al. The Physical Activity 4 Everyone Cluster Randomized Trial: 2-Year Outcomes of a School Physical Activity Intervention Among Adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S.; Skara, S.; Ames, S.L. Substance Abuse Among Adolescents. Subst. Use Misuse 2008, 43, 1802–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrila, A.S.; Artiges, E.; Massicotte, J.; Miranda, R.; Vulser, H.; Bézivin-Frere, P.; Lapidaire, W.; Lemaître, H.; Penttilä, J.; The IMAGEN Consortium; et al. Sleep habits, academic performance, and the adolescent brain structure. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Arshad, A.; Finkelstein, Y.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions for Adolescent Substance Abuse: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2016, 59, S61–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, S.; Conley, S.; Batten, J.; Grey, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral sleep interventions for adolescents and emerging adults. Sleep Med. Rev. 2020, 54, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlak, J.A.; Dupre, E.P. Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaap, R.; Bessems, K.; Otten, R.; Kremers, S.; van Nassau, F. Measuring implementation fidelity of school-based obesity prevention programmes: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.; Lubben, F.; Hogarth, S. Bringing science to life: A synthesis of the research evidence on the effects of context-based and STS approaches to science teaching. Sci. Educ. 2007, 91, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Griffiths, J.; Godfrey, K.; Hanson, M.; Galloway, I.; Azaola, M.C.; Harman, K.; Byrne, J.; Inskip, H. Developing teenagers’ views on their health and the health of their future children. Heal. Educ. 2012, 112, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, J.; Blanton, H.; Dodge, T. Peer Influences on Risk Behavior: An Analysis of the Effects of a Close Friend. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viner, R.M.; Ozer, E.M.; Denny, S.; Marmot, M.; Resnick, M.; Fatusi, A.; Currie, C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]