Perceived Physical Literacy Levels in Spanish Adolescents: Differences Between Sexes and Age Groups

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Ethics

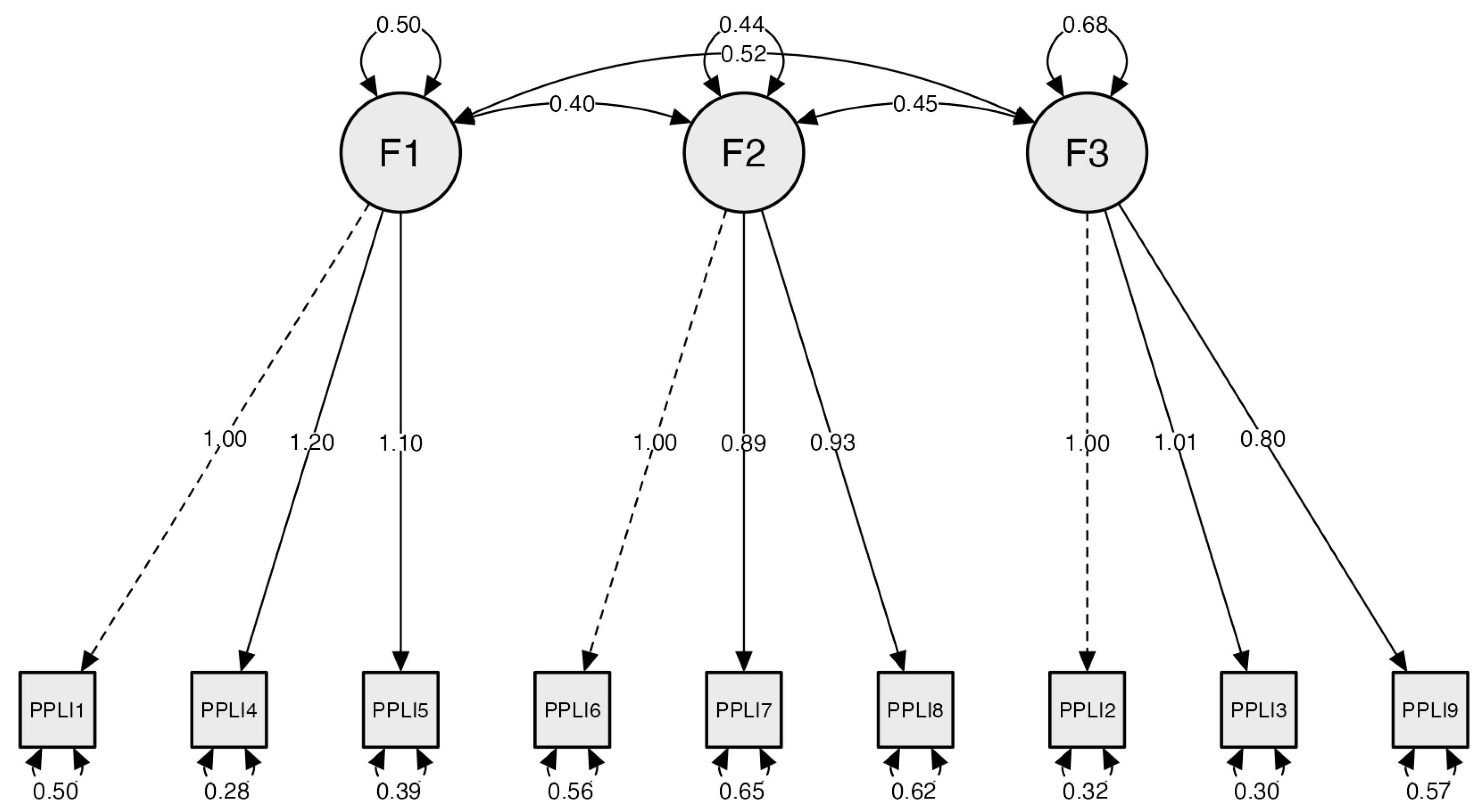

2.4. Perceived Physical Literacy (PPL)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Whitehead, M. The Concept of Physical Literacy. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. 2001, 6, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, P. Emergence of Physical Literacy in Physical Education: Some Curricular Repercussions. Phys. Educ. Sport. Pedagog. 2023, 28, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Adsuar, J.C.; Raimundo, A.; Salazar-Sepúlveda, G.; Contreras-Barraza, N.; Muñoz-Urtubia, N. The Bibliometric Analysis of Studies on Physical Literacy for a Healthy Life. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical Fitness in Childhood and Adolescence: A Powerful Marker of Health. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezondet, C.; Gandrieau, J.; Nguyen, P.; Zunquin, G. Perceived Physical Literacy Is Associated with Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Body Composition and Physical Activity Levels in Secondary School Students. Children 2023, 10, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Tárraga-López, P.J.; García-Hermoso, A. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Reliability, and Validation of the Spanish Perceived Physical Literacy Instrument for Adolescents (S-PPLI). J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2023, 21, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sum, R.K.W.; Ha, A.S.C.; Cheng, C.F.; Chung, P.K.; Yiu, K.T.C.; Kuo, C.C.; Yu, C.K.; Wang, F.J. Construction and Validation of a Perceived Physical Literacy Instrument for Physical Education Teachers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eighmy, K.E.; Lightner, J.S.; Grimes, A.R.; Miller, T. Physical Literacy of Marginalized Middle School Adolescents in Kansas City Public Schools. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2022, 34, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesic, M.G.; Peric, M.; Gilic, B.; Manojlovic, M.; Drid, P.; Modric, T.; Znidaric, Z.; Zenic, N.; Pajtler, A. Are Health Literacy and Physical Literacy Independent Concepts? A Gender-Stratified Analysis in Medical School Students from Croatia. Children 2022, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.M.; Sum, R.K.W.; Leung, E.F.L.; Ng, R.S.K. Relationship between Perceived Physical Literacy and Physical Activity Levels among Hong Kong Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Franco-García, J.M.; Mayordomo-Pinilla, N.; Pazzi, F.; Galán-Arroyo, C. Physical Activity and Emotional Regulation in Physical Education in Children Aged 12–14 Years and Its Relation with Practice Motives. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano-Mairena, J.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Rodal, M.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L. Role of Satisfaction with Life, Sex and Body Mass Index in Physical Literacy of Spanish Children. Children 2024, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, K.B.; Foley, B.C.; Wilhite, K.; Booker, B.; Lonsdale, C.; Reece, L.J. Sport Participation and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Jiménez, R.A.; Fonseca del Pozo, F.J.; Jiménez Moral, G.; Fruet-Cardozo, J.V. Analysis of Health Habits, Vices and Interpersonal Relationships of Spanish Adolescents, Using SEM Statistical Model. Heliyon 2020, 6, e64699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W. A Spreadsheet for Deriving a Confidence Interval, Mechanistic Inference and Clinical Inference from a P Value. Sportscience 2007, 11, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Longmuir, P.E.; Barnes, J.D.; Belanger, K.; Anderson, K.D.; Bruner, B.; Copeland, J.L.; Delisle Nyström, C.; Gregg, M.J.; Hall, N.; et al. Physical Literacy Levels of Canadian Children Aged 8-12 Years: Descriptive and Normative Results from the RBC Learn to Play-CAPL Project. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomkinson, G.R.; Carver, K.D.; Atkinson, F.; Daniell, N.D.; Lewis, L.K.; Fitzgerald, J.S.; Lang, J.J.; Ortega, F.B. European Normative Values for Physical Fitness in Children and Adolescents Aged 9-17 Years: Results from 2 779 165 Eurofit Performances Representing 30 Countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denche-Zamorano, Á.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Muñoz-Bermejo, L.; Rojo-Ramos, J.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; Godoy-Cumillaf, A.; Barrios-Fernandez, S. A Cross-Sectional Study on Self-Perceived Health and Physical Activity Level in the Spanish Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Muñoz, V.M.; Águila-Lara, E.; Ávila-García, M.; Segura-Díaz, J.M.; Campos-Garzón, P.; Barranco-Ruiz, Y.; Saucedo-Araujo, R.G.; Villa-González, E. Assessment of Perceived Physical Literacy and Its Relationship with 24-Hour Movement Guidelines in Adolescents: The ENERGYCO Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.E.; Gill, M.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Rice, L.N.; Crespi, C.M.; Koniak-Griffin, D.; Cole, B.L.; Upchurch, D.M.; Prelip, M.L. Physical Activity Correlates in Middle School Adolescents: Perceived Benefits and Barriers and Their Determinants. J. School Nursing 2019, 35, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Orden EFP/754/2022, de 28 de Julio, Por La Que Se Establece El Currículo y Se Regula La Ordenación de La Educación Secundaria Obligatoria; BOE Núm. 181 (29 de Julio de 2022); Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional: Madrid, Spain; pp. 109246–110002. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2022/07/28/efp754 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Bałdyka, J.; Kopiczko, A. Relationship between Bone Mineral Density and Body Compositions, Strength, Type of Sport Competition, Vitamin D and Birth-Related Factors in Elite Polish Track and Field Athletes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Kinesiol. 2024, 18, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiola, G.; Aliberti, S.; D’Isanto, T.; D’Elia, F. The Contest for Movement Education Teachers in Primary Schools: Issues of the Written Exam. Acta Kinesiol. 2024, 18, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subscale 1. Self-perception and self-confidence. | |

| PPL1 | I am physically fit, according to my age. |

| PPL4 | I have self-management skills for fitness. |

| PPL5 | I have self-assessment skills for health. |

| Subscale 2. Self-expression and communication with others. | |

| PPL6 | I have strong social skills. |

| PPL7 | I have confidence in wild/natural survival. |

| PPL8 | I am able to handle problems and difficulties. |

| Subscale 3. Knowledge and understanding. | |

| PPL2 | I have a positive attitude and interest in sports. |

| PPL3 | I value myself or others by doing sports. |

| PPL9 | I am aware of the health-related benefits of sports. |

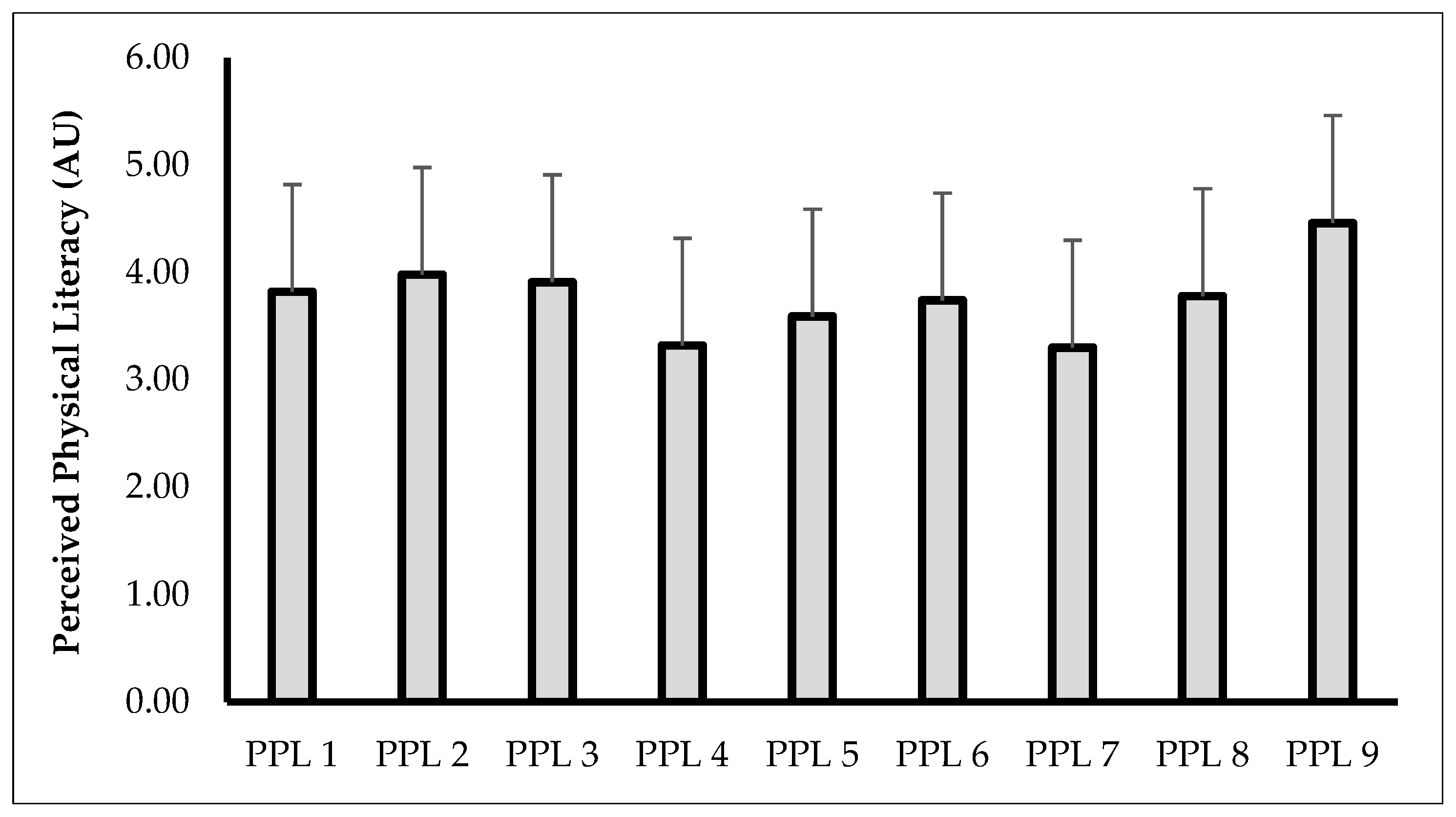

| Domains | Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | %Diff. | p | ES | |

| PPL1 | 3.85 | 1.09 | 3.79 | 1.02 | 1.69 | 0.413 | 0.06 |

| PPL2 | 4.29 | 0.98 | 3.62 | 1.19 | 15.38 | <0.001 | 0.67 |

| PPL 3 | 4.11 | 0.99 | 3.68 | 1.09 | 10.53 | <0.001 | 0.44 |

| Subscale 1 | 11.04 | 2.78 | 10.40 | 2.55 | 5.80 | 0.002 | 0.23 |

| PPL 4 | 3.48 | 1.15 | 3.15 | 1.16 | 9.44 | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| PPL 5 | 3.71 | 0.99 | 3.46 | 0.99 | 6.60 | 0.001 | 0.25 |

| PPL 6 | 3.82 | 1.02 | 3.65 | 1.08 | 4.60 | 0.027 | 0.17 |

| Subscale 2 | 11.12 | 2.34 | 10.49 | 2.40 | 5.67 | <0.001 | 0.27 |

| PPL 7 | 3.52 | 1.12 | 3.06 | 1.16 | 13.23 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| PPL 8 | 3.78 | 0.95 | 3.79 | 0.98 | 0.18 | 0.926 | 0.01 |

| PPL 9 | 4.50 | 0.84 | 4.40 | 0.81 | 2.29 | 0.100 | 0.12 |

| Subscale 3 | 12.90 | 2.34 | 11.71 | 2.51 | 9.22 | <0.001 | 0.51 |

| PPLtotal | 35.05 | 6.45 | 32.57 | 6.35 | 7.07 | <0.001 | 0.38 |

| Domains | Early Compulsory Secondary Education | Late Compulsory Secondary Education | Baccalaureate | Early vs. Late (%Diff.; p; ES) | Early vs. Baccalaureate (%Diff.; p; ES) | Late vs. Baccalaureate (%Diff.; p; ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPL 1 | 3.79 ± 1.13 | 3.85 ± 1.06 | 3.82 ± 0.94 | 1.61; 1.000; 0.05 | 0.87; 1.000; 0.03 | −0.73; 1.000; 0.03 |

| PPL 2 | 4.01 ± 1.16 | 3.96 ± 1.14 | 3.97 ± 1.09 | 1.32; 1.000; 0.11 | 1.02; 1.000; 0.04 | 0.30; 1.000; 0.01 |

| PPL 3 | 3.94 ± 1.12 | 3.85 ± 1.06 | 3.95 ± 0.99 | 2.23; 1.000; 0.08 | 0.13; 1.000; 0.09 | 2.36; 1.000; 0.09 |

| Subscale 1 | 10.62 ± 2.72 | 10.78 ± 2.78 | 10.84 ± 2,52 | 1.48; 1.000; 0.06 | 2.03; 1.000; 0.09 | 0.55; 1.000; 0.02 |

| PPL 4 | 3.27 ± 1.15 | 3.35 ± 1.20 | 3.35 ± 1.14 | 2.39; 1.000; 0.07 | 2.32; 1.000; 0.07 | 0.06; 1.000; 0.01 |

| PPL 5 | 3.56 ± 1.05 | 3.58 ± 0.97 | 3.66 ± 0.97 | 0.67; 1.000; 0.02 | 2.89; 0.816; 0.10 | 2.24; 1.000; 0.08 |

| PPL 6 | 3.73 ± 1.12 | 3.69 ± 1.07 | 3.84 ± 0.91 | 1.23; 1.000; 0.04 | 2.94; 0.797; 0.10 | 4.14; 0.341; 0.15 |

| Subscale 2 | 10.84 ± 2.43 | 10.67 ± 2.48 | 11.03 ± 2.20 | 6.70; 1.000; 0.07 | 1.72; 1.000; 0.09 | 3.26; 0.336; 0.16 |

| PPL 7 | 3.40 ± 1.12 | 3.29 ± 1.22 | 3.20 ± 1.13 | 3.21; 0.850;0.10 | 5.89; 0.224; 0.18 | 2.77; 1.000; 0.07 |

| PPL 8 | 3.71 ± 0.98 | 3.70 ± 0.97 | 4.00 ± 0.90 | 0.43; 1.000; 0.02 | 7.03; 0.007; 0.29 | 7.43; 0.004; 0.31 |

| PPL 9 | 4.35 ± 0.91 | 4.45 ± 0.83 | 4.61 ± 0.66 | 2.16; 0.546; 0.11 | 5.74; 0.003; 0.29 | 3.66; 0.098; 0.20 |

| Subscale 3 | 12.30 ± 2.65 | 12.25 ± 2.49 | 12.53 ± 2.25 | 0.41; 1.000; 0.02 | 1.84; 1.000; 0.10 | 2.23; 0.756; 0.12 |

| PPLtotal | 33.75 ± 6.78 | 33.68 ± 6.66 | 34.38 ± 5.92 | 0.23; 1.000; 0.01 | 1.81; 0.973; 0.09 | 2.04; 0.792; 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albéniz-Pérez, R.; Castillo, D.; Duarte-Mendes, P.; Raya-González, J. Perceived Physical Literacy Levels in Spanish Adolescents: Differences Between Sexes and Age Groups. Children 2025, 12, 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081017

Albéniz-Pérez R, Castillo D, Duarte-Mendes P, Raya-González J. Perceived Physical Literacy Levels in Spanish Adolescents: Differences Between Sexes and Age Groups. Children. 2025; 12(8):1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081017

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbéniz-Pérez, Raquel, Daniel Castillo, Pedro Duarte-Mendes, and Javier Raya-González. 2025. "Perceived Physical Literacy Levels in Spanish Adolescents: Differences Between Sexes and Age Groups" Children 12, no. 8: 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081017

APA StyleAlbéniz-Pérez, R., Castillo, D., Duarte-Mendes, P., & Raya-González, J. (2025). Perceived Physical Literacy Levels in Spanish Adolescents: Differences Between Sexes and Age Groups. Children, 12(8), 1017. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12081017