Perspectives from Systems-Level Key Informants on Optimizing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Adolescents and Young Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

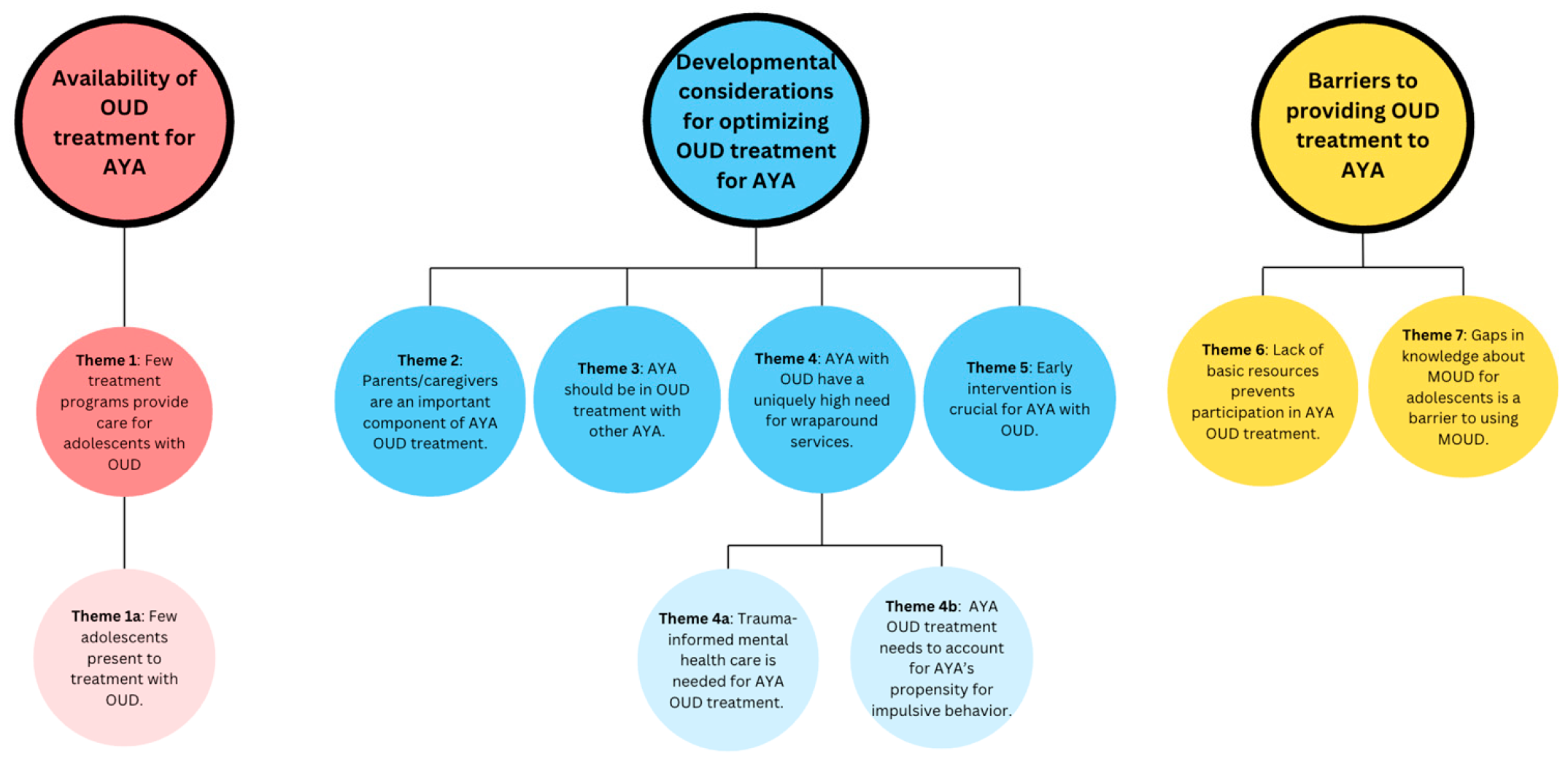

3.1. Availability of OUD Treatment for AYA

3.1.1. Theme 1: Few Treatment Programs Provide Care for Adolescents with OUD, Despite a Need for OUD Treatment Among This Age Group

Theme 1a: Few Adolescents Present to Treatment with OUD, Making It Difficult for Treatment Programs to Sustain Adolescent-Specific Programming

3.2. Developmental Considerations for Optimizing OUD Treatment for AYA

3.2.1. Theme 2: Parents/Caregivers Are an Important Component of AYA OUD Treatment Because They Are a Crucial Part of Youth’s Environment. Thus, Psychoeducation and Skills-Building for Parents Would Be Useful for Helping Them to Support Their Youth

“The perception on the part of the caregiver is, ‘well, when you were 10, I could just walk in your room and do whatever, and you also haven’t been behaving yourself, so you’re still in my house, and I can do whatever.’ There’s a huge developmental need…around figuring out how to have privacy and how to earn privacy and how to earn freedom in ways that make sense”.(clinic leader)

3.2.2. Theme 3: AYA Should Be in Treatment with Other AYA to Increase Relatability, Establish Peer Recovery Connections, and Share Treatment Experiences That Are Unique to the AYA Population

“I think having a group that’s specifically tailored to young adults could be nice to talk about some of the unique challenges that present themselves with this population or just feeling like there’s an opportunity to connect with your peers who are going through shared or similar experiences”.(clinic leader)

“As they’ve been exposed to older individuals who’ve been struggling with addiction for a long time…I think it was really kind of terrifying and scared them in a way that wasn’t productive, or they couldn’t relate to that person. They felt that it was just a really different thing than what they were experiencing”.(clinic leader)

“You have kids that are developmentally impulsive, they hear about somebody in their mid-20’s, it looks pretty cool and they’re doing something novel and they say, ‘well, I’m gonna try that,’ even though in the whatever meeting or group they might have been in, it was meant to be ‘don’t try it”.(policy maker)

3.2.3. Theme 4: Along with Treatment Focused on OUD, Youth Have a Uniquely High Need for Wraparound Services, Including Mental Healthcare, Development of Basic Life Skills, and Vocational/Educational Assistance

“I really think that [AYA OUD treatment], if it’s properly done, it needs to be an interdisciplinary team of providers, counselors, social workers, case managers, to make sure that that one patient, one person, getting cared for in a holistic manner on a whole bunch of different levels and dimensions”.(clinic leader)

“When [youth with OUD] stop using, you know, a lot of times the use covered up or masked a lot of their feelings and emotions. And so then they have this flood of kind of feelings and emotions that they’ve never had to cope with before, and suddenly they’re like having to figure out what to do with that”.(Participant 4, treatment provider)

Theme 4a: There Is a High Need to Integrate Trauma-Informed Mental Health Care into OUD Treatment Due to the High Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Among the AYA OUD Population

“They have so much trauma going on. They need a quick fix to get over depression, anger, anxiety, trauma…or they’ve seen horrible things happen”.(policymaker)

3.2.4. Theme 5: Early Intervention Is Crucial for AYA with OUD to Prevent Progression to More Severe OUD

“You have a certain trajectory in your life. The more quickly you address deviance from that trajectory the better…If you’re addressing either the pre-opioid uses or the early opioid uses, the chances of impacting the trajectory of their life and more effectively getting back on is gonna be much more effective”.(policy maker)

3.3. Barriers to Providing OUD Treatment for AYA

3.3.1. Theme 6: AYA Often Struggle with a Lack of Basic Resources That Prevent Participation in OUD Treatment

“If it’s working parents, it’s really difficult to get a kid from school to the program on time and then for the parents to make the time, especially if they are financially strained in any way to make the time to participate in family meetings let alone set up that transportation”.(treatment provider)

3.3.2. Theme 7: Stigma and Gaps in Knowledge from Patients, Family Members, and Providers About MOUD for Adolescents Is a Barrier to Using MOUD for This Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OUD | Opioid use disorder |

| AYA | Adolescents and young adults |

| MOUD | Medications for opioid use disorder |

| FBT | Family-based treatment |

References

- SAMHSA. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023.

- Lim, J.K.; Earlywine, J.J.; Bagley, S.M.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Hadland, S.E. Polysubstance Involvement in Opioid Overdose Deaths in Adolescents and Young Adults, 1999–2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 194–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Godvin, M.; Shover, C.L.; Gone, J.P.; Hansen, H.; Schriger, D.L. Trends in Drug Overdose Deaths Among US Adolescents, January 2010 to June 2021. JAMA 2022, 327, 1398–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Bruner, A.; Barnett, G.; Fishman, M. Opioid Use Disorders. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022.

- Alinsky, R.H.; Zima, B.T.; Rodean, J.; Matson, P.A.; Larochelle, M.R.; Adger, H., Jr.; Bagley, S.M.; Hadland, S.E. Receipt of Addiction Treatment After Opioid Overdose Among Medicaid-Enrolled Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e195183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACAP. Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Youth. Available online: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Policy_Statements/2020/Opioid_Use_Disorder_Treatment_Youth.aspx (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Medication-Assisted Treatment of Adolescents With Opioid Use Disorders. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder; CFR Part 8; eFCR, 2024; Volume 42.

- Feder, K.A.; Krawczyk, N.; Saloner, B. Medication-Assisted Treatment for Adolescents in Specialty Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, H.K. Adolescent-Only Substance Abuse Treatment: Availability and Adoption of Components of Quality. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009, 36, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, A.; Harvey, N.; Kamanu, M.; Tendulkar, S.; Fleary, S. Barriers, Facilitators, and Disparities in Retention for Adolescents in Treatment for Substance Use Disorders: A Qualitative Study with Treatment Providers. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pielech, M.; Modrowski, C.; Yeh, J.; Clark, M.A.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Beaudoin, F.L.; Becker, S.J.; Miranda, R. Provider Perceptions of Systems-Level Barriers and Facilitators to Utilizing Family-Based Treatment Approaches in Adolescent and Young Adult Opioid Use Disorder Treatment. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2024, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.S.; MacQueen, K.M.; Namey, E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4129-7167-6. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in Qualitative Research: Exploring Its Conceptualization and Operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; McCluskey, S.; Turley, E.; King, N. The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2015, 12, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, J.W.; Dennis, M.L.; Funk, R.; Mataczynski, M.J.; Godley, M.D. Trends and Age-Related Disparities in Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Admissions for Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2022, 132, 108584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.A.; Wilson, J.D. Management of Opioid Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders Among Youth. Pediatrics 2020, 145, S153–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.K.; Herr-Zaya, K.; Weinstein, Z.; Whelton, K.; Perfas, F., Jr.; Castro-Donlan, C.; Straus, J.; Schoneman, K.; Botticelli, M.; Levy, S. Results of a Statewide Survey of Adolescent Substance Use Screening Rates and Practices in Primary Care. Subst. Use Addict. J. 2012, 33, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Volkow, N.D.; Wargo, E.M. Overdose Prevention Through Medical Treatment of Opioid Use Disorders. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeman, S.E.; Larochelle, M.R.; Ameli, O.; Chaisson, C.E.; McPheeters, J.T.; Crown, W.H.; Azocar, F.; Sanghavi, D.M. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1920622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Medication for Adolescents and Young Adults With Opioid Use Disorder. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2021, 68, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.; Beetham, T.; Smith, N.; Englander, H.; Hadland, S.E.; Bagley, S.M.; Korthuis, P.T. Treatments Used Among Adolescent Residential Addiction Treatment Facilities in the US, 2022. JAMA 2023, 329, 1983–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDAPS—Buprenorphine Prescribing Requirements and Limitations. Available online: https://pdaps.org/datasets/buprenorphine-prescribing-requirements-and-limitations (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Peavy, K.M.; Adwell, A.; Owens, M.D.; Banta-Green, C.J. Perspectives on Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Adolescents: Results from a Provider Learning Series. Subst. Use Misuse 2023, 58, 160–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA. Buprenorphine Quick Start Guide. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/quick-start-guide.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Bagley, S.M.; Hadland, S.E.; Carney, B.L.; Saitz, R. Addressing Stigma in Medication Treatment of Adolescents With Opioid Use Disorder. J. Addict. Med. 2017, 11, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, S.M.; Schoenberger, S.F.; della Bitta, V.; Lunze, K.; Barron, K.; Hadland, S.E.; Park, T.W. Ambivalence and Stigma Beliefs About Medication Treatment Among Young Adults With Opioid Use Disorder: A Qualitative Exploration of Young Adults’ Perspectives. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horigian, V.E.; Anderson, A.R.; Szapocznik, J. Family-Based Treatments for Adolescent Substance Use. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 2016, 25, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, A.; Bobek, M.; Dauber, S.; Henderson, C.E.; McLeod, B.D.; Southam-Gerow, M.A. Distilling the Core Elements of Family Therapy for Adolescent Substance Use: Conceptual and Empirical Solutions. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse 2017, 26, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIDA. Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide, 3rd ed.; National Institute on Drug Abuse: Rockville, MD, USA; National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Hogue, A.; Henderson, C.E.; Becker, S.J.; Knight, D.K. Evidence Base on Outpatient Behavioral Treatments for Adolescent Substance Use, 2014–2017: Outcomes, Treatment Delivery, and Promising Horizons. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 47, 499–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Wilson, S.J.; Lipsey, M.W. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2013, 44, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paino, M.; Aletraris, L.; Roman, P. The Relationship Between Client Characteristics and Wraparound Services in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Centers. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2016, 77, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leza, L.; Siria, S.; López-Goñi, J.J.; Fernández-Montalvo, J. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Substance Use Disorder (SUD): A Scoping Review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 221, 108563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tice, P.; Lipari, R.N.; Van Horn, S.L. The CBHSQ Report, Substance Use Among 12th Grade Aged Youths, by Dropout Status; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- Hogue, A.; Becker, S.J.; Wenzel, K.; Henderson, C.E.; Bobek, M.; Levy, S.; Fishman, M. Family Involvement in Treatment and Recovery for Substance Use Disorders among Transition-Age Youth: Research Bedrocks and Opportunities. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2021, 129, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadland, S.E.; Wharam, J.F.; Schuster, M.A.; Zhang, F.; Samet, J.H.; Larochelle, M.R. Trends in Receipt of Buprenorphine and Naltrexone for Opioid Use Disorder Among Adolescents and Young Adults, 2001–2014. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniran, E.A.; Quinn, M.; Liu, Y.; Brooks, B.; Pack, R.P. Exploring the Determinants of Treatment Completion Among Youth Who Received Medication-Assisted Treatment in the United States. Healthcare 2025, 13, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Treatment with Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Different Populations. In Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives; Mancher, M., Leshner, A.I., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Ericzén, M.J.; Jenkins, M.M.; Haine-Schlagel, R. Therapist, Parent, and Youth Perspectives of Treatment Barriers to Family-Focused Community Outpatient Mental Health Services. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2013, 22, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukes, L.M.; Di Folco, S.; Kearney, L.; Sawrikar, V. Barriers and Facilitators to Engaging Mothers and Fathers in Family-Based Interventions: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2024, 55, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | Code Definition | Relevant Interview Question |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1a Quality of available services for AYA | Comments and opinions about the adequacy or inadequacy of services available for AYA with OUD. | What treatment services are you aware of for AYA with OUD in the state? |

| 2.2 Services needed for AYA and unmet treatment needs | Identified treatment needs for AYA with OUD that are not being addressed in the current system of care or services that we need more of. Can also include descriptions of programs that used to be offered and are no longer available. | What is your perception of the need for clinical services for AYA with OUD in this state? |

| 4.1 Developmental needs and considerations for AYA | Comments about unique developmental considerations for AYA, including if current treatments are not a good fit for their needs. | What are some of the unique needs of AYA served by your organization? |

| 5.1 Barriers and facilitators to providing treatment to AYA | What gets in the way of providing treatment to AYA as well as the strengths of the clinic that help them (or would help them) to treat AYA with OUD. | What barriers might there be to providing treatment to AYA with OUD in your organization? |

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <25 years old | 0 | 0.0% |

| 25–34 years old | 8 | 26.7% |

| 35–44 years old | 10 | 33.3% |

| 45–54 years old | 4 | 13.3% |

| 55–64 years old | 7 | 23.3% |

| 65–74 years old | 1 | 3.3% |

| 75 years or older | 0 | 0.0% |

| Gender Identity | ||

| Male | 6 | 20.0% |

| Female | 24 | 80.0% |

| Non-binary/third gender | 0 | 0.0% |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hispanic/Latinx | ||

| Yes | 1 | 3.3% |

| No | 29 | 96.7% |

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0% |

| Asian | 0 | 0.0% |

| Black or African American | 1 | 3.3% |

| White | 28 | 93.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0% |

| Other | 2 | 6.7% |

| Years Practicing in Current Agency | ||

| <1 year | 4 | 13.3% |

| 1–2 years | 8 | 26.7% |

| >2–5 years | 8 | 26.7% |

| >5–10 years | 2 | 6.7% |

| >10–15 years | 5 | 16.7% |

| >15 years | 3 | 10.0% |

| Treats adolescents (<18 years) | ||

| Treats adolescents | 13 | 43.3% |

| Does not treat adolescents | 17 | 56.7% |

| Primary Role | ||

| Leader | 10 | 33.3% |

| Provider | 11 | 36.7% |

| Advocate | 3 | 10.0% |

| State Policy | 3 | 10.0% |

| Hospital Policy | 3 | 10.0% |

| Level of Education | ||

| Bachelor’s | 10 | 33.3% |

| Master’s | 11 | 36.7% |

| Ph.D. | 6 | 20.0% |

| MD | 3 | 10.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeh, J.; Modrowski, C.; Aguirre, I.; Portis, S.; Miranda, R., Jr.; Pielech, M. Perspectives from Systems-Level Key Informants on Optimizing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Adolescents and Young Adults. Children 2025, 12, 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070876

Yeh J, Modrowski C, Aguirre I, Portis S, Miranda R Jr., Pielech M. Perspectives from Systems-Level Key Informants on Optimizing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Adolescents and Young Adults. Children. 2025; 12(7):876. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070876

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeh, Jasper, Crosby Modrowski, Isabel Aguirre, Samantha Portis, Robert Miranda, Jr., and Melissa Pielech. 2025. "Perspectives from Systems-Level Key Informants on Optimizing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Adolescents and Young Adults" Children 12, no. 7: 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070876

APA StyleYeh, J., Modrowski, C., Aguirre, I., Portis, S., Miranda, R., Jr., & Pielech, M. (2025). Perspectives from Systems-Level Key Informants on Optimizing Opioid Use Disorder Treatment for Adolescents and Young Adults. Children, 12(7), 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12070876