Clinical and Research Insights from Pre-Emptive Early Intervention for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Case Series

Highlights

- Early and pre-emptive structured interventions may have the potential to enhance long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes.

- Siblings of children with ASD may develop atypical trajectories in several developmental domains.

- Considering all developmental domains is a key point of early interventions for children at risk of neurodevelopmental disorders.

- A multidimensional approach with the active involvement of parents is crucial for the effectiveness of early intervention programs.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- Group 1—Clinical Monitoring Group (CM): Siblings of TD children with no signs of concern;

- Group 2—Active Monitoring Group (AM): Siblings of ASD children with no signs of concern;

- Group 3—Early Intervention Group (EI): Siblings classified as “with signs of concern” at the baseline evaluation.

2.2. Outcome Measures

- Griffiths Scales of Child Development, 3rd Edition (Griffiths-3). Griffiths-3 is considered the gold standard for assessing overall child development in children aged 0–6 years. It provides a comprehensive profile of a child’s strengths and needs across five developmental domains: foundations of learning, language and communication, eye–hand coordination, personal–social–emotional, and gross motor skills [14]. The Griffiths-3 yields standardized scores based on normative data, allowing each child’s performance to be compared with age-matched peers and identifying areas that may require closer monitoring or intervention. In this study, the test was administered at all three assessment time points, enabling the evaluation of developmental trajectories over time and the detection of early signs of neurodevelopmental vulnerability relative to typical development.

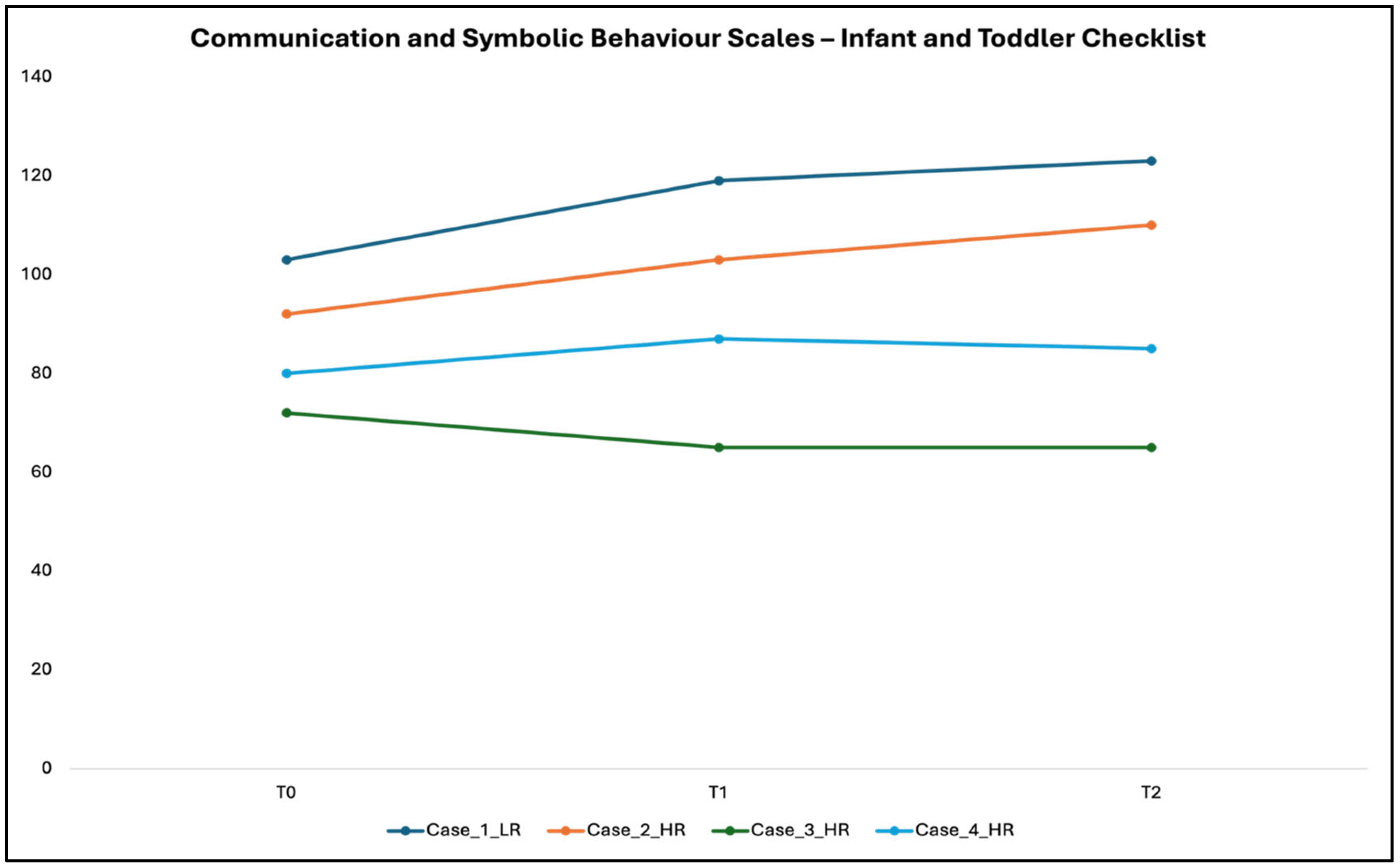

- The Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales—Infant–Toddler Checklist (CSBS-IT-C). It is a standardized developmental screening tool that measures seven key predictors of language and communication in children aged 6–24 months [15]. The checklist can be administered to parents in an interview format, with explanations to clarify each item. Completion typically requires 5–10 min. Significantly, the CSBS-ITC scores are based on normative data, which allows each child’s performance to be compared with age-matched peers. Scores exceeding established “concern” thresholds indicate potential early signs of ASD, guiding the identification of infants who may benefit from closer monitoring or intervention. In this study, the CSBS-ITC was administered at all three assessment time points, enabling both the detection of early signs of concern and the tracking of developmental trajectories relative to standardized norms.

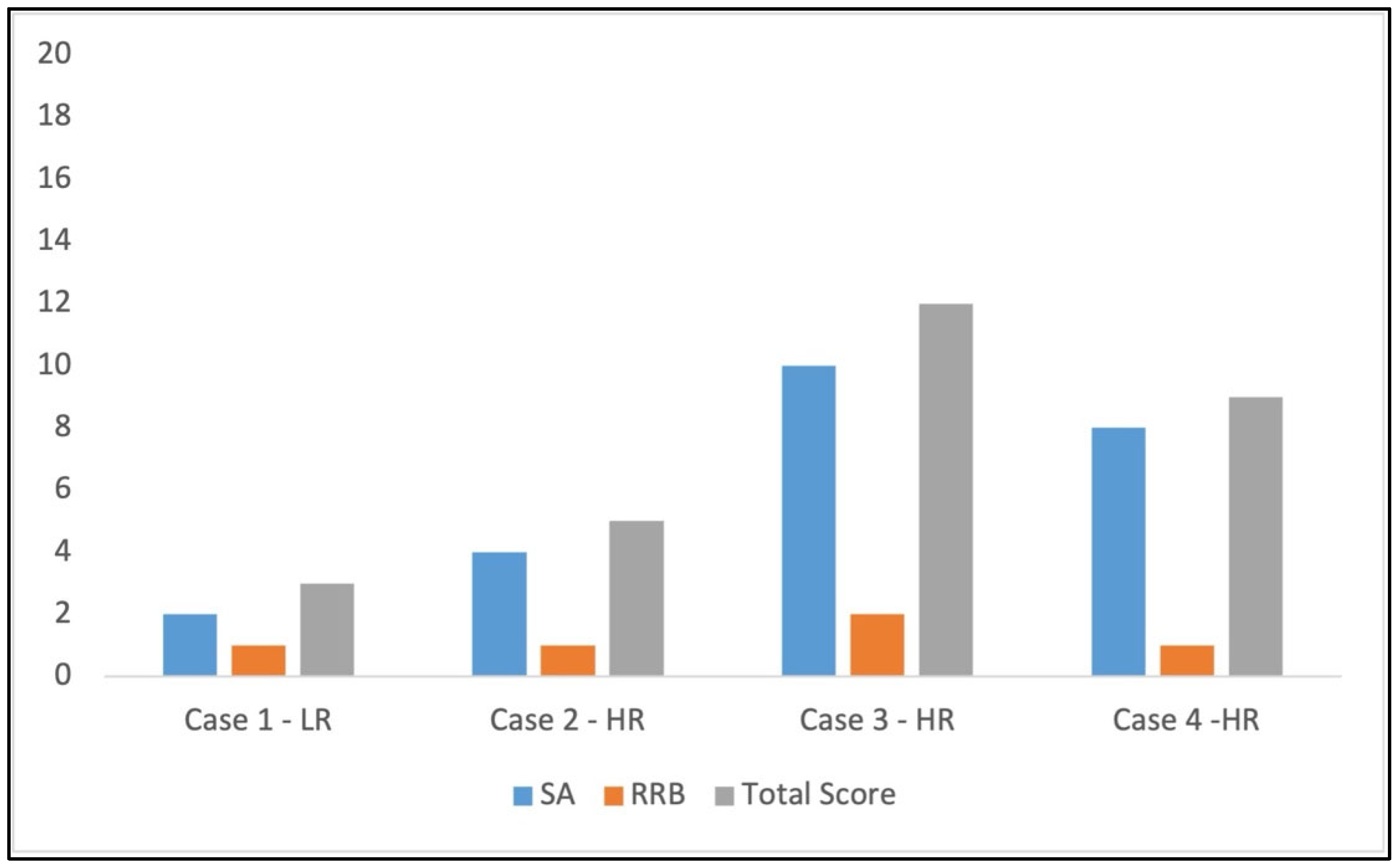

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2)- Toddler Module. The ADOS-2 is a semi-structured, standardized assessment of communication, social interaction, play/imaginative use of materials, and restricted/repetitive patterns of interest to assess the presence of ASD symptoms [16]. The Toddler Module is used specifically for 12–30-month-old children. The administration involves direct observation using hierarchical manualized procedures and progressive prompts. Every behavior/symptom is assessed using a Likert scale (0–3) and coded on an algorithm based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. This test was administered only at T2.

- Parent Interactions with Children: Checklist of Observations Linked to Outcomes (PICCOLO). This is an observational measure in which a mother–child interaction is video recorded, and trained observers code specific parenting behaviors known to predict children’s early social, cognitive, and language development [17]. Specifically, the PICCOLO examines four domains of parenting, including behaviors such as affection, responsiveness, encouragement, and teaching. Each domain is scored on a 0–2 Likert scale. This project used the PICCOLO at all three time points.

- Satisfaction Survey: Parents of children in Groups 2 and 3 were asked to complete an anonymous, project-specific survey immediately following the intervention (T1) to assess their satisfaction with the services provided between T0 and T1. The questionnaire takes approximately 5 min to complete and consists of 15 items, each rated on a 5-point scale (from 1, “not at all,” to 5, “very much”).

2.3. Interventions

- Active Monitoring Group: This multimodal and ecological approach has been planned for siblings of children with ASD who do not show early signs of concern. Following the environmental enrichment paradigm, this pre-emptive program has been structured explicitly for HR siblings. This choice is based both on the evidence that siblings of ASD children without early signs of concern can have a higher probability of developing later other neurodevelopmental disorders (for example, language disorder) [18] and on the data that supported as also no-ASD high-risk siblings show different patterns of behaviors in temperament, motor, social and linguistic domains in comparison to low-risk children, also in the absence of a specific diagnosis [19,20,21,22,23]. For these reasons, children in this group are enrolled in 90-min sessions monthly for 6 months. Sessions are performed by an expert neuro and psychomotor therapist for developmental age (TNPEE) [24], supported by a child neuropsychiatrist or psychologist. A parent is always present and actively involved in the session. During sessions, by using play and following the self-initiated behaviors and interests of the child, professionals and parents can share and implement new strategies to promote the achievement of developmental milestones and the child’s active participation in everyday activities. Some practical advice for managing children at home can also be given to parents with more significant concerns. More details about “Active Monitoring” are reported in Annunziata et al., 2025 [13].

- Early Intervention Group: The early intervention program aims to promote postural–motor, socio-communicative, and cognitive skills using a multidimensional, naturalistic, and family-centered approach. The intervention has been planned by considering the child’s sensory profile and individualizing and tailoring objectives and strategies to each child’s functioning and needs. This approach has been ideated and implemented based on scientific literature that suggests that ASD siblings have a higher risk of developing ASD or other neurodevelopmental disorders [18,25], but also on data that indicate early sensory–motor development may have important prognostic implications in ASD [26,27,28,29]. Children in this group are enrolled in a 90-min parent-coaching session once a week for six months, led by an expert neuro and psychomotor therapist for developmental age (TNPEE) [24] and accompanied by a child neuropsychiatrist or psychologist. A parent (preferably the mother) is always present and actively involved in the intervention. During the sessions, clinicians work with parents to identify ways to incorporate the same strategies into daily life. Also, they encourage parents to organize playful sessions at home for regular stimulation, with a goal dose of 20–30 min per day, according to their child’s availability. Sessions may also contain a small psychoeducation component on common early parenting challenges such as sleep, crying, and feeding. More details about Early Intervention are reported in Annunziata et al., 2025 [13].

3. Results

3.1. Scores at Griffiths-3

3.2. Scores at CSBS-IT-C

3.3. Scores at ADOS-2 Toddler Module

3.4. Scores at PICCOLO

| Dyad 1 | Dyad 2 | Dyad 3 | Dyad 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICCOLO | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 |

| Affection | 13 | 7 | 12 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Responsiveness | 12 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| Encouragement | 10 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 9 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Teaching | 7 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 8 |

| Total Score | 42 | 38 = | 47 ⇑ | 35 | 40 ⇑ | 47 ⇑ | 15 | 5 ⇓ | 16 = | 21 | 34 ⇑ | 42 ⇑ |

3.5. Scores at Satisfaction Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| NDD | Neurodevelopmental Disorder |

| ERI-SIBS | Early Recognition and Intervention in SIBlingS at High Risk for Neurodevelopment Disorders |

| CM | Clinical Monitoring |

| AM | Active Monitoring Group |

| EI | Early Intervention |

| CSBS-IT-C | Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales—Infant–Toddler Checklist |

| ADOS-2 | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition |

| PICCOLO | Parent Interactions with Children: Checklist of Observations Linked to Outcomes |

| TNPEE | Neuro and psychomotor therapist for developmental age |

References

- Bonnier, C. Evaluation of early stimulation programs for enhancing brain development. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2008, 97, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioni, G.; Inguaggiato, E.; Sgandurra, G. Early intervention in neurodevelopmental disorders: Underlying neural mechanisms. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2016, 58, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorna, O.; Cioni, G.; Guzzetta, A. Principles of Early Intervention, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncelli, L.; Braschi, C.; Spolidoro, M.; Begenisic, T.; Sale, A.; Maffei, L. Nurturing brain plasticity: Impact of environmental enrichment. Cell Death Differ. 2010, 17, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, G.; Cioni, G.; Tinelli, F. Multisensory-based rehabilitation approach: Translational insights from animal models to early intervention. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, F.Y.; Fatemi, A.; Johnston, M.V. Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddi, D.; Subashi, E.; Middei, S.; Bellocchio, L.; Lemaire-Mayo, V.; Guzmán, M.; Crusio, W.E.; D’AMato, F.R.; Pietropaolo, S. Early social enrichment rescues adult behavioral and brain abnormalities in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbugino, L.; Centofante, E.; D’Amato, F.R. Early social enrichment improves social motivation and skills in a monogenic mouse model of autism, the Oprm1−/− mouse. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 5346161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.A.; Sullivan, E.; Engelstad, A.M. Annual research review: Early intervention viewed through the lens of developmental neuroscience. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2024, 65, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, A.J.O.; Varcin, K.J.; Pillar, S.; Billingham, W.; Alvares, G.A.; Barbaro, J.; Bent, C.A.; Blenkley, D.; Boutrus, M.; Chee, A.; et al. Effect of preemptive intervention on developmental outcomes among infants showing early signs of autism: A randomized clinical trial of outcomes to diagnosis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, e213298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, N.M.; Senturk, D.; Scheffler, A.; Brian, J.A.; Carver, L.J.; Charman, T.; Chawarska, K.; Curtin, S.; Hertz-Piccioto, I.; Jones, E.J.H.; et al. Developmental trajectories of infants with multiplex family risk for autism. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, P.S. Pre-emptive intervention for autism spectrum disorder: Theoretical foundations and clinical translation. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, S.; Purpura, G.; Piazza, E.; Meriggi, P.; Fassina, G.; Santos, L.; Ambrosini, E.; Marchetti, A.; Manzi, F.; Massaro, D.; et al. Early recognition and intervention in SIBlingS at high risk for neurodevelopment disorders (ERI-SIBS): A controlled trial of an innovative and ecological intervention for siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 12, 1467783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, L.; Foxcroft, C.; Green, E.; Bloomfield, S.; Cronje, J.; Hurter, K.; Lane, H.; Marais, R.; Marx, C.; McAlinden, P.; et al. Griffiths III Manual. Part 1: Overview, Development and Psychometric Properties, 3rd ed.; Hogrefe Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, K.; Carter, C.; Weinfeld, M.; Desmond, J.; Hazin, R.; Bjork, R.; Gallagher, N. Detecting, studying, and treating autism early: The one-year well-baby check-up approach. J. Pediatr. 2011, 159, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, C.; Luyster, R.; Gotham, K.; Guthrie, W. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part II): Toddler Module; Western Psychological Services: Torrance, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roggman, L.A.; Cook, G.A.; Innocenti, M.S.; Jump Norman, V.; Christiansen, K. Parenting interactions with children: Checklist of observations linked to outcomes (PICCOLO) in diverse ethnic groups. Infant Ment. Health J. 2013, 34, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiranta-Olkoniemi, E.; Cheslack-Postava, K.; Sucksdorff, D.; Suominen, A.; Gyllenberg, D.; Chudal, R.; Leivonen, S.; Gissler, M.; Brown, A.S.; Sourander, A. Risk of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders among siblings of probands with autism spectrum disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.; Fenoglio, A.; Wolff, J.J.; Schultz, R.T.; Botteron, K.N.; Dager, S.R.; Estes, A.M.; Hazlett, H.C.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Piven, J.; et al. Examining the factor structure and discriminative utility of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire–Revised in infant siblings of autistic children. Child Dev. 2022, 93, 1398–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiades, S.; Szatmari, P.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.; Brian, J.; Roberts, W.; Smith, I.; Vaillancourt, T.; Roncadin, C.; Garon, N. A prospective study of autistic-like traits in unaffected siblings of probands with autism spectrum disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2013, 70, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacrey, L.A.R.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.; Brian, J.; Smith, I.M. The reach-to-grasp movement in infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A high-risk sibling cohort study. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2018, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammer, I.; Bedford, R.; Elsabbagh, M.; Garwood, H.; Pasco, G.; Tucker, L.; Volein, A.; Johnson, M.H.; Charman, T. Behavioural markers for autism in infancy: Scores on the Autism Observational Scale for Infants in a prospective study of at-risk siblings. Infant Behav. Dev. 2015, 38, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrus, N.; Hall, L.P.; Paterson, S.J.; Elison, J.T.; Wolff, J.J.; Swanson, M.R.; Parish-Morris, J.; Eggebrecht, A.T.; Pruett, J.R.; Hazlett, H.C.; et al. Language delay aggregates in toddler siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2018, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purpura, G.; Coratti, G. Neuro and psychomotor therapist of developmental age professional in Italy: An anomaly or an opportunity? Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2024, 6, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, J.B.; Swanson, M.R.; Meera, S.S.; Grzadzinski, R.L.; Shen, M.D.; Burrows, C.A.; Wolff, J.J.; Pandey, J.; John, T.S.; Estes, A.; et al. Quantitative trait variation in ASD probands and toddler sibling outcomes at 24 months. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2020, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.W.; Armstrong, V.; Duku, E.; Richard, A.; Franchini, M.; Brian, J.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.E.; Sacrey, L.R.; Roncadin, C.; et al. Early trajectories of motor skills in infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capelli, E.; Crippa, A.; Riboldi, E.M.; Beretta, C.; Siri, E.; Cassa, M.; Molteni, M.; Riva, V. Prospective interrelation between sensory sensitivity and fine motor skills during the first 18 months predicts later autistic features. Dev. Sci. 2024, 28, e13573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBarton, E.S.; Landa, R.J. Infant motor skill predicts later expressive language and autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Infant Behav. Dev. 2019, 54, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, A.N.; Galloway, J.C.; Landa, R.J. Relationship between early motor delay and later communication delay in infants at risk for autism. Infant Behav. Dev. 2012, 35, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotham, K.; Pickles, A.; Lord, C. Trajectories of autism severity in children using standardized ADOS scores. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1278–e1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waizbard-Bartov, E.; Ferrer, E.; Young, G.S.; Heath, B.; Rogers, S.; Nordahl, C.W.; Solomon, M.; Amaral, D.G. Trajectories of autism symptom severity change during early childhood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Itzchak, E.; Watson, L.R.; Zachor, D.A. Cognitive ability is associated with different outcome trajectories in autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatmari, P.; Georgiades, S.; Duku, E.; Bennett, T.A.; Bryson, S.; Fombonne, E.; Mirenda, P.; Roberts, W.; Smith, I.M.; Vaillancourt, T.; et al. Developmental trajectories of symptom severity and adaptive functioning in an inception cohort of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, F.; Chericoni, N.; Costanzo, V.; Baldini, S.; Billeci, L.; Cohen, D.; Muratori, F. Reciprocity in interaction: A window on the first year of life in autism. Autism Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 705895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallen, A.; Taylor, E.; Salmi, J.; Haataja, L.; Vanhatalo, S.; Airaksinen, M. Early gross motor performance is associated with concurrent prelinguistic and social development. Pediatr. Res. 2025, 98, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Low | High | High | High |

| ERI-SIBS Group | Group 1 Clinical Monitoring | Group 2 Active Monitoring | Group 3 Early Intervention | Group 3 Early Intervention |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 40 | 40 | 39 | 38 |

| Birth Weight (g) | 3600 | 2950 | 3150 | 3105 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Age of parents (Mother/Father) | 39 ys/43 ys | 40 ys/43 ys | 28 ys/39 ys | 35 ys/42 ys |

| Age at recruitment (months) | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Age at the start of intervention (months) | --- | 9 | 9 | 8, 5 |

| Griffiths-III GDQ at T0 | 113 | 114 | 79 | 82 |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Griffiths-III | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 |

| Foundation of Learning | 109 | 105 = | 119 ⇑ | 128 | 100 ⇓ | 110 ⇓ | 91 | 76 ⇓ | 48 ⇓ | 93 | 105 ⇑ | 92 = |

| Language and Communication | 125 | 115 ⇓ | 104 ⇓ | 117 | 109 ⇓ | 104 ⇓ | 78 | 81 = | 69 ⇓ | 85 | 106 ⇑ | 96 ⇑ |

| Eye–Hand Coordination | 98 | 120 ⇑ | 113 ⇑ | 106 | 126 ⇑ | 104 = | 92 | 71 ⇓ | 52 ⇓ | 95 | 109 ⇑ | 105 ⇑ |

| Personal–Social–Emotional | 105 | 111 ⇑ | 107 = | 119 | 123 = | 114 = | 76 | 54 ⇓ | 75 = | 78 | 110 ⇑ | 96 ⇑ |

| Grossmotor | 122 | 114 ⇓ | 113 ⇓ | 107 | 128 ⇑ | 118 ⇑ | 86 | 67 ⇓ | 74 ⇓ | 75 | 119 ⇑ | 74 = |

| Global Developmental Quotient | 119 | 116 = | 113 ⇓ | 114 | 116 = | 113 = | 79 | 61 ⇓ | 57 ⇓ | 82 | 106⇑ | 90 ⇑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purpura, G.; Annunziata, S.; Biancardi, S.; Brivio, M.; Caporali, C.; Mantegazza, G.; Piazza, E.; Restelli, A.; Cavallini, A. Clinical and Research Insights from Pre-Emptive Early Intervention for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Case Series. Children 2025, 12, 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111489

Purpura G, Annunziata S, Biancardi S, Brivio M, Caporali C, Mantegazza G, Piazza E, Restelli A, Cavallini A. Clinical and Research Insights from Pre-Emptive Early Intervention for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Case Series. Children. 2025; 12(11):1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111489

Chicago/Turabian StylePurpura, Giulia, Silvia Annunziata, Stefania Biancardi, Michelle Brivio, Camilla Caporali, Giulia Mantegazza, Elena Piazza, Alice Restelli, and Anna Cavallini. 2025. "Clinical and Research Insights from Pre-Emptive Early Intervention for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Case Series" Children 12, no. 11: 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111489

APA StylePurpura, G., Annunziata, S., Biancardi, S., Brivio, M., Caporali, C., Mantegazza, G., Piazza, E., Restelli, A., & Cavallini, A. (2025). Clinical and Research Insights from Pre-Emptive Early Intervention for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Case Series. Children, 12(11), 1489. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111489