Associations Between Electronic Vapor Product Use and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among High School Students in the United States; A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis

Highlights

- •

- The use of electronic vapor products (EVPs) in adolescents was found to be correlated with increased current opioid misuse

- •

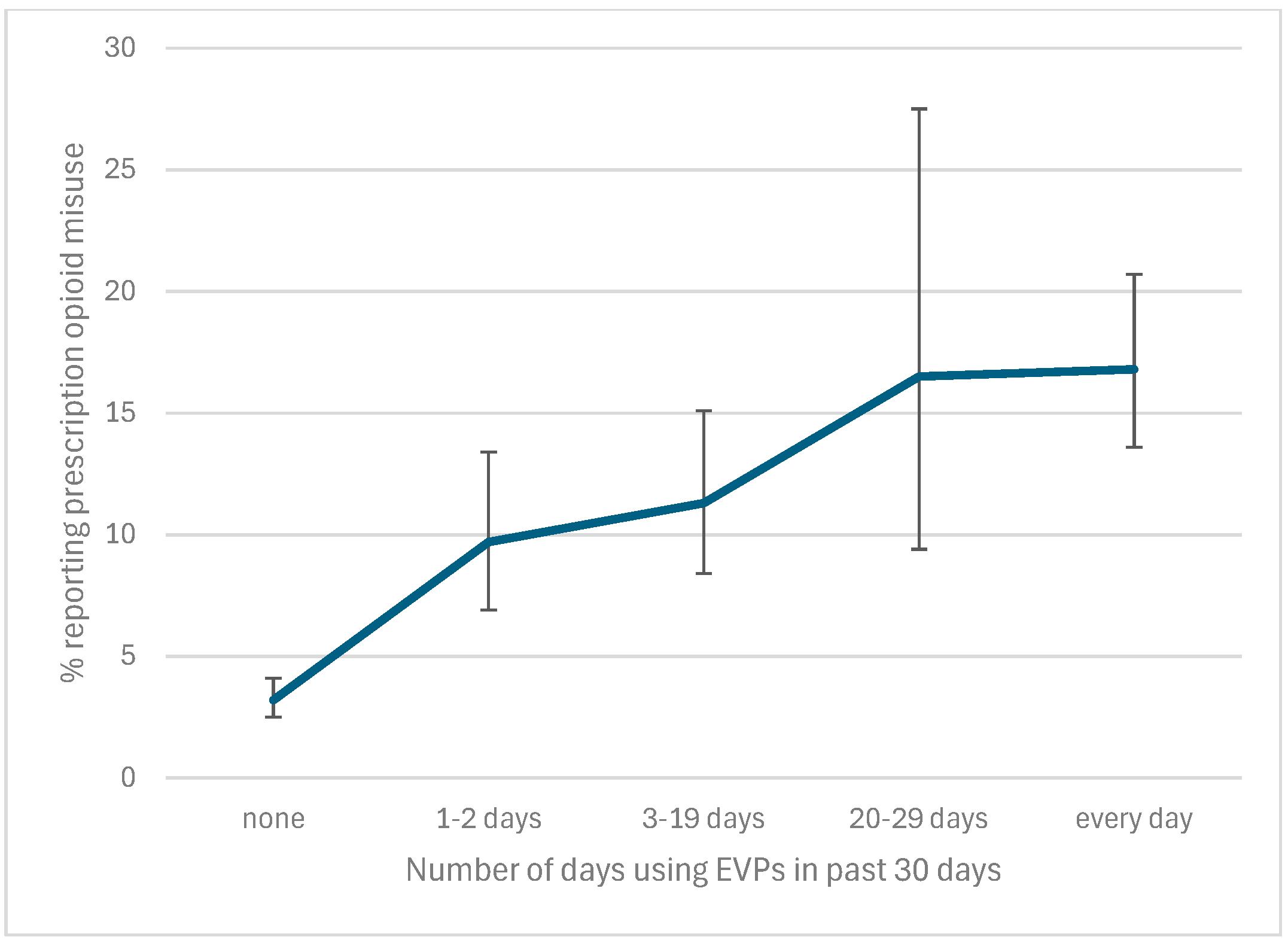

- This relationship had a dose-dependent effect, with an increased frequency of EVP use correlating with an increased prevalence of current opioid misuse

- •

- Adolescents with EVP use may be at increased risk for opioid misuse and should be identified for targeted screening and education

- •

- Public health measures aiming to reduce EVP use in adolescents may want to highlight an increased risk of opioid misuse as a potential sequela of EVP use initiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Electronic Vapor Product Use

2.2.2. Prescription Opioid Misuse

2.2.3. Covariates

2.2.4. Study Sample and Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVP | Electronic Vapor Product |

| YRBS | Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

References

- American Lung Association. Health Effects of Smoking. Available online: https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/health-effects/smoking (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Mejia, M.C.; Adele, A.; Levine, R.S.; Hennekens, C.H.; Kitsantas, P. Trends in Cigarette Smoking Among United States Adolescents. Ochsner J. 2023, 23, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Rahman, S.; Lutfy, K. E-cigarettes may serve as a gateway to conventional cigarettes and other addictive drugs. Adv. Drug Alcohol Res. 2023, 3, 11345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, M.A.; Cruz-Cano, R.; Streck, J.M.; Ballis, E.; Weinberger, A.H. Incidence of opioid misuse by cigarette smoking status in the United States. Addict. Behav. 2023, 147, 107837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, A.H.; Gbedemah, M.; Wall, M.M.; Hasin, D.S.; Zvolensky, M.J.; Goodwin, R.D. Cigarette use is increasing among people with illicit substance use disorders in the United States, 2002–2014: Emerging disparities in vulnerable populations. Addiction 2018, 113, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.; Lane, S.D.; Weaver, M.F. Opioid Analgesics and Nicotine: More Than Blowing Smoke. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2015, 29, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, A.; Brener, N.D.; Thornton, J.; Mpofu, J.J.; Harris, W.A.; Roberts, A.M.; Kilmer, G.; Chyen, D.; Whittle, L.; Leon-Nguyen, M.; et al. Overview and Methodology of the Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey—United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Suppl. 2022, 71, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, L.; Conti, A.A.; Hemmati, Z.; Baldacchino, A. The prospective association between the use of E-cigarettes and other psychoactive substances in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edlund, M.J.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L.; Winder, C.R.; Heller, D.C.; Kroutil, L.A.; Lipari, R.N.; Colpe, L.J. Opioid abuse and depression in adolescents: Results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 152, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miech, R.A.; Johnston, L.D.; Patrick, M.E.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G. National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2023: Secondary School Students; Monitoring the Future; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hudgins, J.D.; Porter, J.J.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Bourgeois, F.T. Prescription opioid use and misuse among adolescents and young adults in the United States: A national survey study. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. E-Cigarettes (Vapes). Smoking and Tobacco Use. 31 January 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/e-cigarettes/index.html (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Rajabi, A.; Dehghani, M.; Shojaei, A.; Farjam, M.; Motevalian, S.A. Association between tobacco smoking and opioid use: A meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 2019, 92, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zirakzadeh, A.; Shuman, C.; Stauter, E.; Hays, J.T.; Ebbert, J.O. Cigarette Smoking in Methadone Maintained Patients: An Up-to-Date Review. Available online: https://www.eurekaselect.com/article/53186 (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Skurtveit, S.; Furu, K.; Selmer, R.; Handal, M.; Tverdal, A. Nicotine dependence predicts repeated use of prescribed opioids. prospective population-based cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobscha, S.K.; Morasco, B.J.; Duckart, J.P.; Macey, T.; Deyo, R.A. Correlates of prescription opioid initiation and long-term opioid use in veterans with persistent pain. Clin. J. Pain 2013, 29, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, V.M.; Saarni, L.; Parkkari, J.; Koivusilta, L.; Rimpelä, A. Predictors of low back pain hospitalization--a prospective follow-up of 57,408 adolescents. Pain 2008, 139, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrendero, F.; Robledo, P.; Trigo, J.M.; Martín-García, E.; Maldonado, R. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in nicotine dependence and reward: Participation of the endogenous opioid system. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 35, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, M.E.; Schmitz, J.M.; Allen, S.; Grabowski, J.; Pentel, P.; Oliver, A.; Hatsukami, D.K. Bupropion and Naltrexone for Smoking Cessation: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 100, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, W.; Idoko, E.; Montgomery, L.; Smith, M.L.; Merianos, A.L. Concurrent E-cigarette and marijuana use and health-risk behaviors among U.S. high school students. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, S.; Minegishi, M.; Brogna, M.; Ross, J.; Subramaniam, G.; Weitzman, E.R. Screening for Nonmedical Use and Misuse of Prescription Medication by Adolescents. Subst. Use Addict. J. 2025, 46, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yale, S.; McFadden, V.; Mikhailov, T. Adolescents and Electronic Vapor Product Use: A Dangerous Unknown. Adolescents 2023, 3, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 7471) | EVP Use (n = 1367) | No EVP Use (n = 6104) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | Weighted % | 95% CI | |

| Age | |||||||

| 14 years | 19.2 | [17.7, 20.9] | 12.7 | [9.8, 16.5] | 20.6 | [18.8, 22.5] | 0.000 |

| 15 years | 24.8 | [23.2, 26.4] | 20.6 | [17.9, 23.6] | 25.6 | [24.0, 27.3] | |

| 16 years | 25.8 | [24.4, 27.3] | 25.9 | [22.6, 29.5] | 25.8 | [24.2, 27.5] | |

| 17 years | 24.0 | [22.5, 25.6] | 31.3 | [27.8, 35.1] | 22.5 | [21.1, 23.9] | |

| 18 years or older | 6.2 | [5.3, 7.2] | 9.4 | [7.0, 12.5] | 5.5 | [4.7, 6.4] | |

| Female | |||||||

| Male | 52.6 | [50.9, 54.3] | 44.2 | [41.2, 47.2] | 54.3 | [52.6, 56.1] | 0.000 |

| Female | 47.4 | [45.7, 49.1] | 55.8 | [52.8, 58.8] | 45.7 | [43.9, 47.4] | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 52.9 | [48.1, 57.5] | 60.8 | [56.1, 65.3] | 51.2 | [46.2, 56.2] | 0.000 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9.9 | [7.4, 13.1] | 7.2 | [5.3, 9.6] | 10.4 | [7.7, 14.0] | |

| Hispanic | 9.4 | [7.5, 11.8] | 8.4 | [5.7, 12.2] | 9.6 | [7.8, 11.9] | |

| Asian | 5.6 | [3.3, 9.4] | 1.4 | [0.9, 2.3] | 6.5 | [3.8, 10.8] | |

| Am Indian/Alaska Native | 0.7 | [0.5, 1.0] | 1.2 | [0.8, 1.8] | 0.6 | [0.4, 0.9] | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other PI | 0.3 | [0.2, 0.4] | 0.4 | [0.1, 1.5] | 0.3 | [0.2, 0.4] | |

| Multiple | 21.2 | [19.3, 23.3] | 20.5 | [17.7, 23.6] | 21.4 | [19.3, 23.6] | |

| Current tobacco (other than EVP) use | |||||||

| No | 99.3 | [99.0, 99.4] | 100 | [99.2–100] | 99.1 | [98.9, 99.3] | |

| Yes | 0.8 | [0.6, 1.0] | 0 | [0.0–0.8] | 0.9 | [0.7, 1.2] | |

| Current marijuana use | |||||||

| No | 86.3 | [84.5, 87.9] | 43.0 | [39.0, 47.1] | 95.3 | [94.1, 96.2] | 0.000 |

| Yes | 13.7 | [12.1, 15.5] | 57.0 | [52.9, 61.0] | 4.7 | [3.8, 5.9] | |

| Current alcohol use | |||||||

| No | 78.8 | [77.0, 80.5] | 31.4 | [27.5, 35.7] | 88.7 | [87.7, 89.6] | 0.000 |

| Yes | 21.2 | [19.5, 23.0] | 68.6 | [64.3, 72.5] | 11.3 | [10.4, 12.3] | |

| Felt sad or hopeless | |||||||

| No | 59.0 | [57.1, 60.8] | 34.0 | [30.3, 37.8] | 64.1 | [62.2, 66.0] | 0.000 |

| Yes | 41.0 | [39.2, 42.9] | 66.0 | [62.2, 69.7] | 35.9 | [34.0, 37.8] | |

| Prevalence of Opioid Misuse | Adjusted Prevalence Ratios | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Weighted % | 95% CI | p-Value | aPR * | 95% CI | p-Value |

| Current electronic vapor use | ||||||

| No | 3.2 | [2.5, 4.1] | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 13.3 | [11.5, 15.4] | 1.8 | [1.4, 2.3] | <0.0001 | |

| Age | ||||||

| 14 years | 5.8 | [4.5, 7.5] | 0.609 | |||

| 15 years | 4.8 | [3.6, 6.4] | 0.7 | [0.5, 1.1] | 0.123 | |

| 16 years | 4.6 | [3.2, 6.7] | 0.6 | [0.4, 0.9] | 0.014 | |

| 17 years | 4.6 | [3.4, 6.2] | 0.6 | [0.4, 0.8] | 0.003 | |

| 18 years or older | 5.4 | [3.9, 7.6] | 0.7 | [0.4, 1.1] | 0.124 | |

| Female | ||||||

| Male | 3.1 | [2.4, 3.9] | <0.0001 | |||

| Female | 7.0 | [5.7, 8.6] | 1.5 | [1.1, 2] | 0.004 | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3.9 | [3.2, 4.8] | 0.004 | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 7.2 | [4.6, 11.1] | 2.1 | [1.3, 3.6] | 0.006 | |

| Hispanic | 5.9 | [4.8, 7.4] | 1.7 | [1.2, 2.4] | 0.008 | |

| Asian | 3.6 | [2.2, 5.9] | 1.4 | [0.9, 2.4] | 0.17 | |

| Am Indian/Alaska Native | 7.0 | [2.3, 19.4] | 1.3 | [0.5, 3.8] | 0.571 | |

| Native Hawaiian/Other PI | 12.5 | [5.1, 27.5] | 2.9 | [1.2, 6.6] | 0.015 | |

| Multiple | 6.2 | [4.6, 8.4] | 1.5 | [1.1, 2] | 0.01 | |

| Current tobacco (other than EVP) use | ||||||

| No | 4.9 | [4.1, 5.8] | 0.193 | |||

| Yes | 12.6 | [2.7, 42.5] | 2.3 | [0.5, 10] | 0.273 | |

| Current marijuana use | ||||||

| No | 3.4 | [2.8, 4.1] | 0.000 | |||

| Yes | 14.7 | [12.4, 17.4] | 1.7 | [1.2, 2.3] | 0.002 | |

| Current alcohol use | ||||||

| No | 3.1 | [2.5, 3.9] | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 11.7 | [10.2, 13.4] | 1.8 | [1.4, 2.4] | <0.0001 | |

| Felt sad or hopeless | ||||||

| No | 2.1 | [1.4, 3.0] | <0.0001 | |||

| Yes | 9.1 | [7.8, 10.4] | 2.6 | [1.8, 3.8] | <0.0001 | |

| Number of Days in Past Month of EVP Use | aPR * | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 days | ref | ||

| 1 or 2 days | 1.8 | [1.3, 2.3] | <0.0001 |

| 3–19 days | 1.5 | [1, 2.2] | 0.078 |

| 20–29 days | 2.2 | [1.4, 3.5] | 0.001 |

| every day | 2.3 | [1.5, 3.5] | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pache, K.M.; Kameni, L.; Groenewald, C.B. Associations Between Electronic Vapor Product Use and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among High School Students in the United States; A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children 2025, 12, 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111476

Pache KM, Kameni L, Groenewald CB. Associations Between Electronic Vapor Product Use and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among High School Students in the United States; A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children. 2025; 12(11):1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111476

Chicago/Turabian StylePache, Killian M., Lionel Kameni, and Cornelius B. Groenewald. 2025. "Associations Between Electronic Vapor Product Use and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among High School Students in the United States; A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis" Children 12, no. 11: 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111476

APA StylePache, K. M., Kameni, L., & Groenewald, C. B. (2025). Associations Between Electronic Vapor Product Use and Prescription Opioid Misuse Among High School Students in the United States; A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Children, 12(11), 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111476