Pathogen Profiles and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Neonatal Sepsis in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

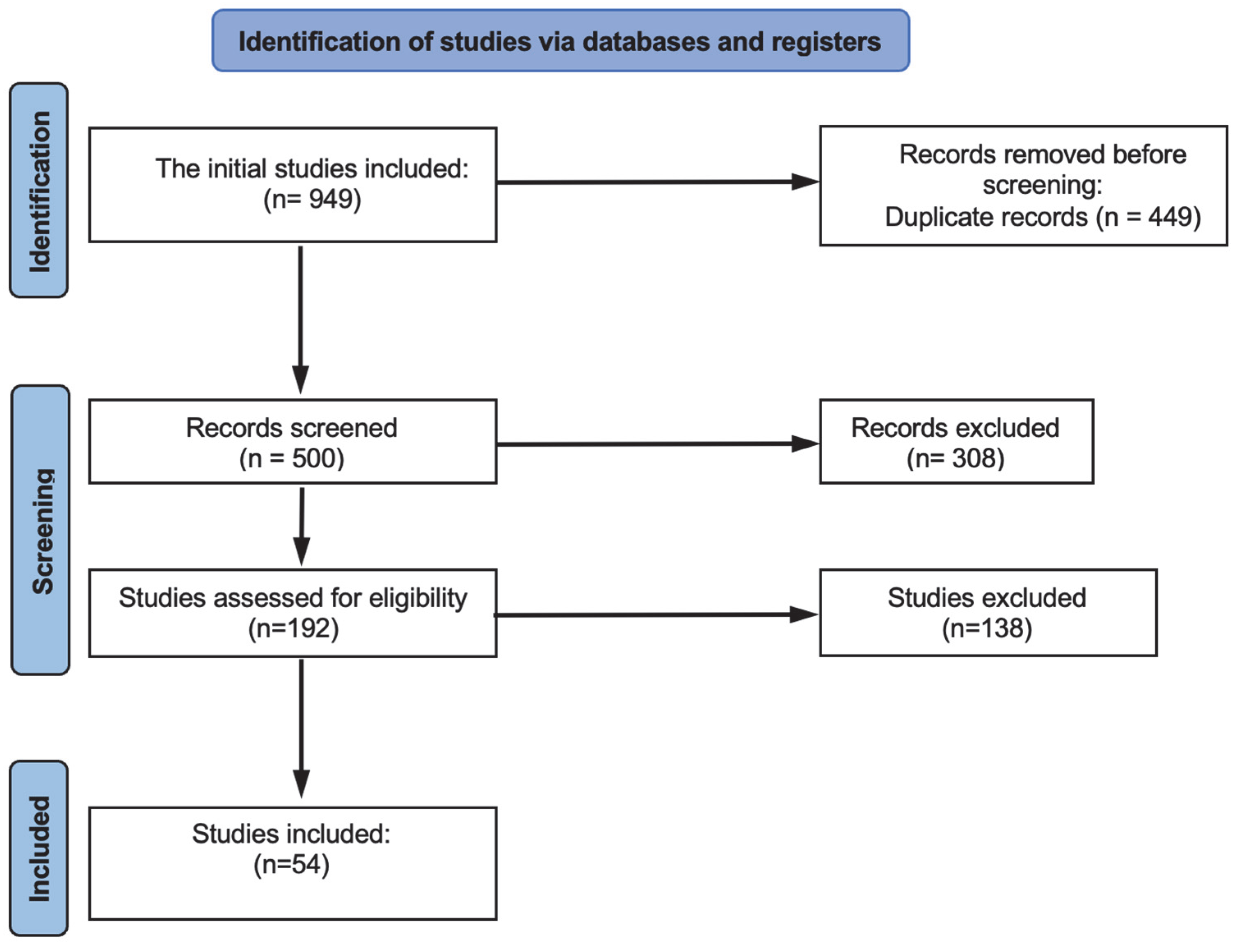

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Development and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment Tool Used (MINORS)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

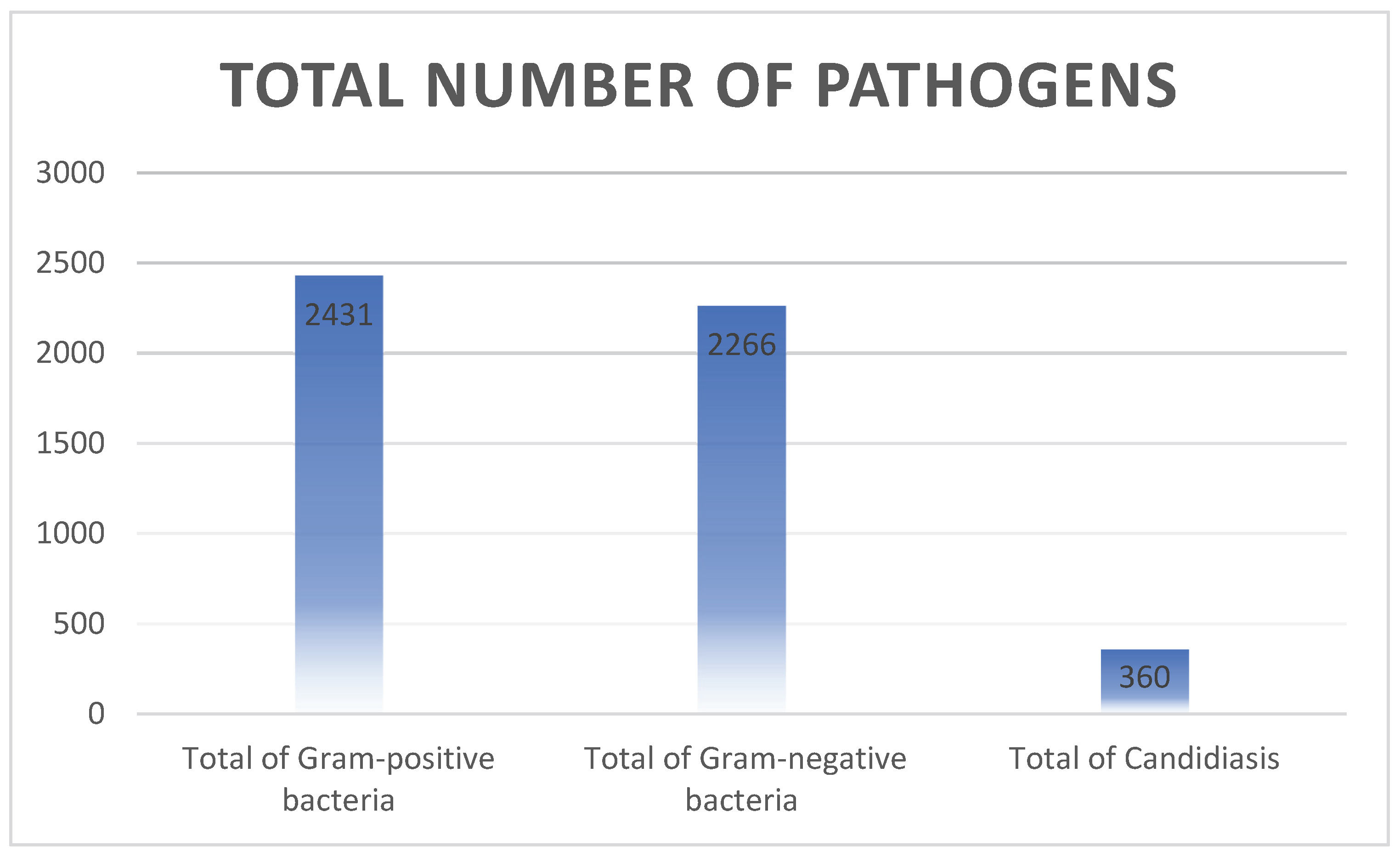

3.2. Distribution of the Pathogen Causing Neonatal Sepsis

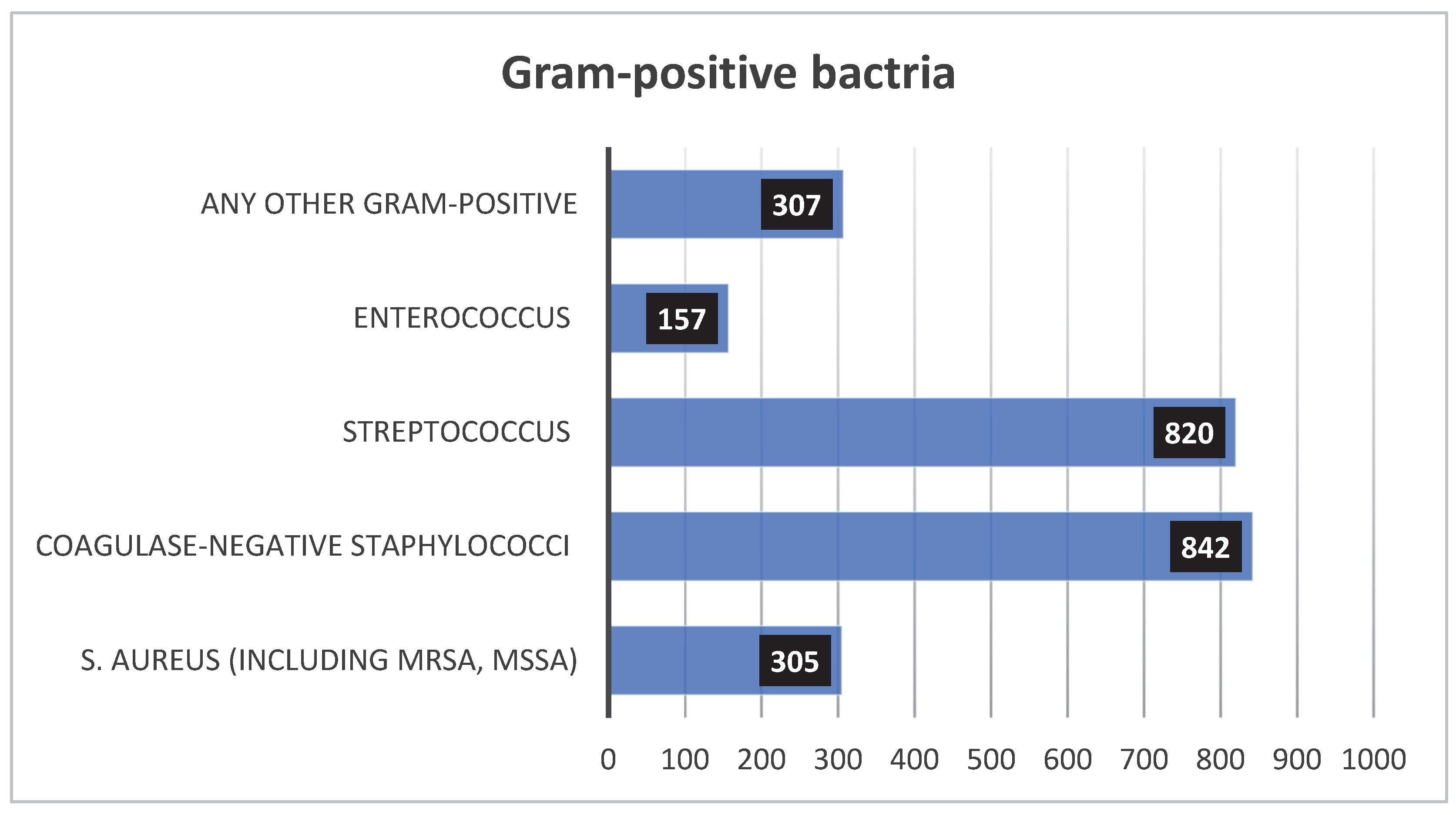

3.2.1. Gram-Positive

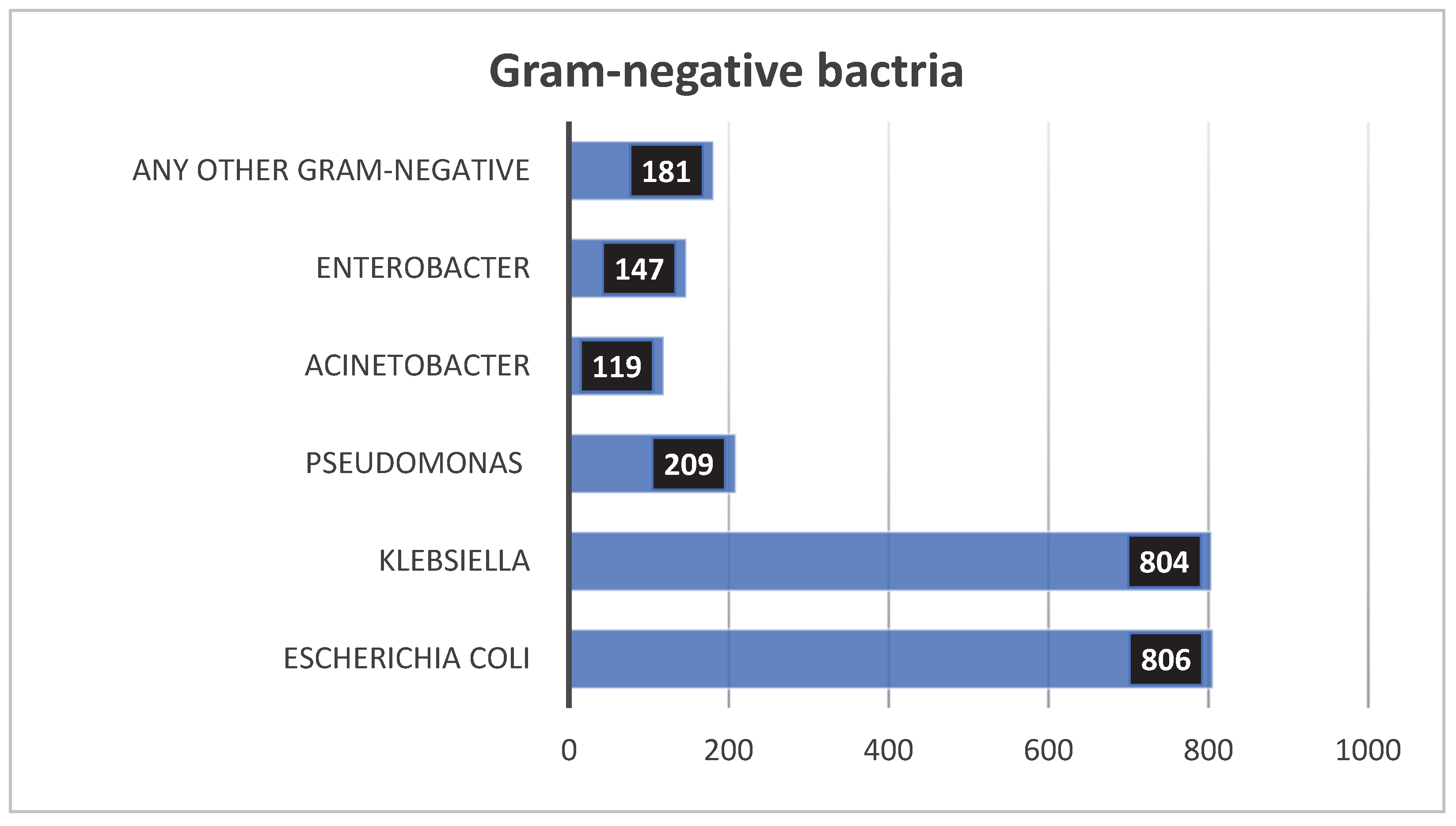

3.2.2. Gram-Negative

3.2.3. Leading Pathogens of Neonatal Sepsis

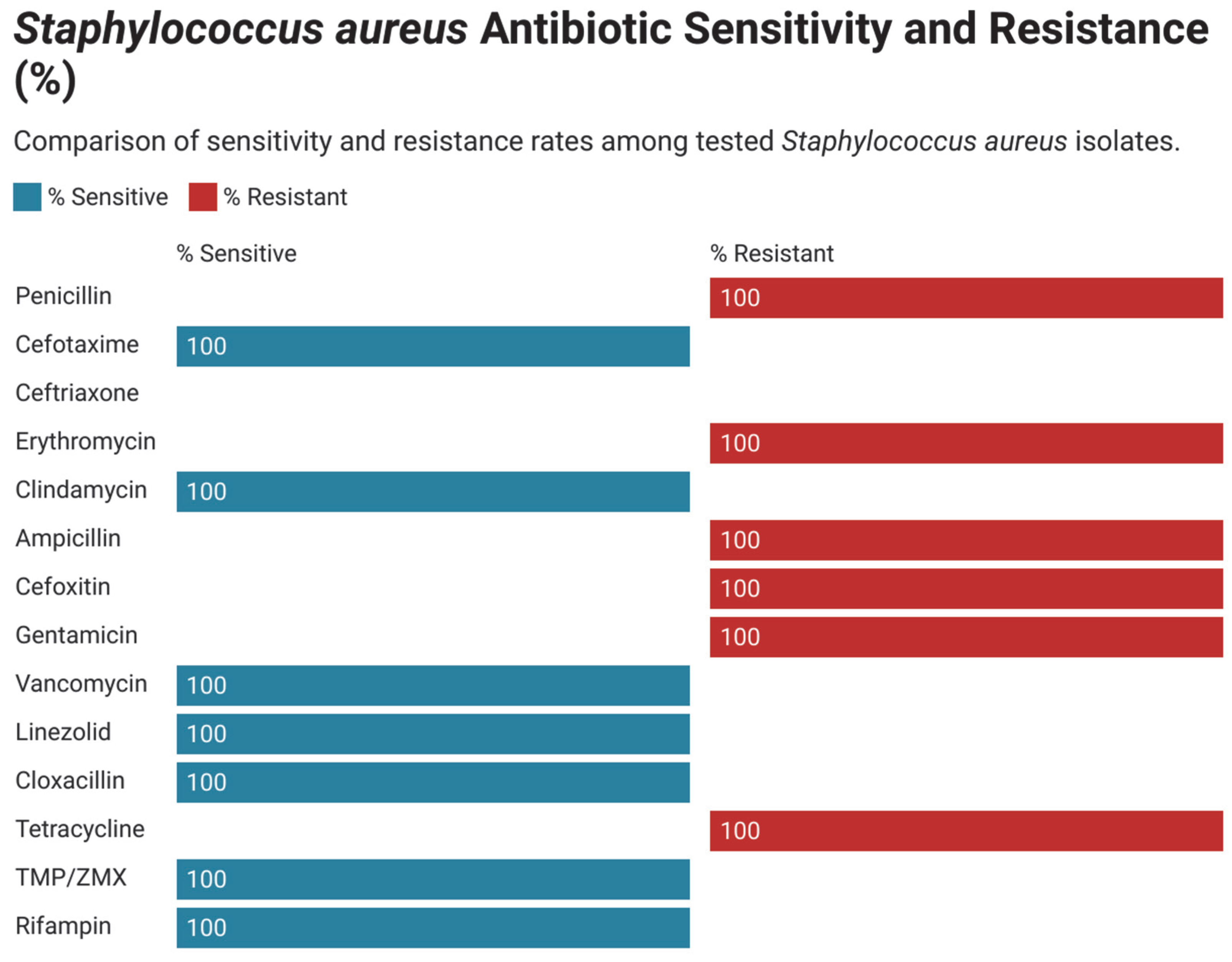

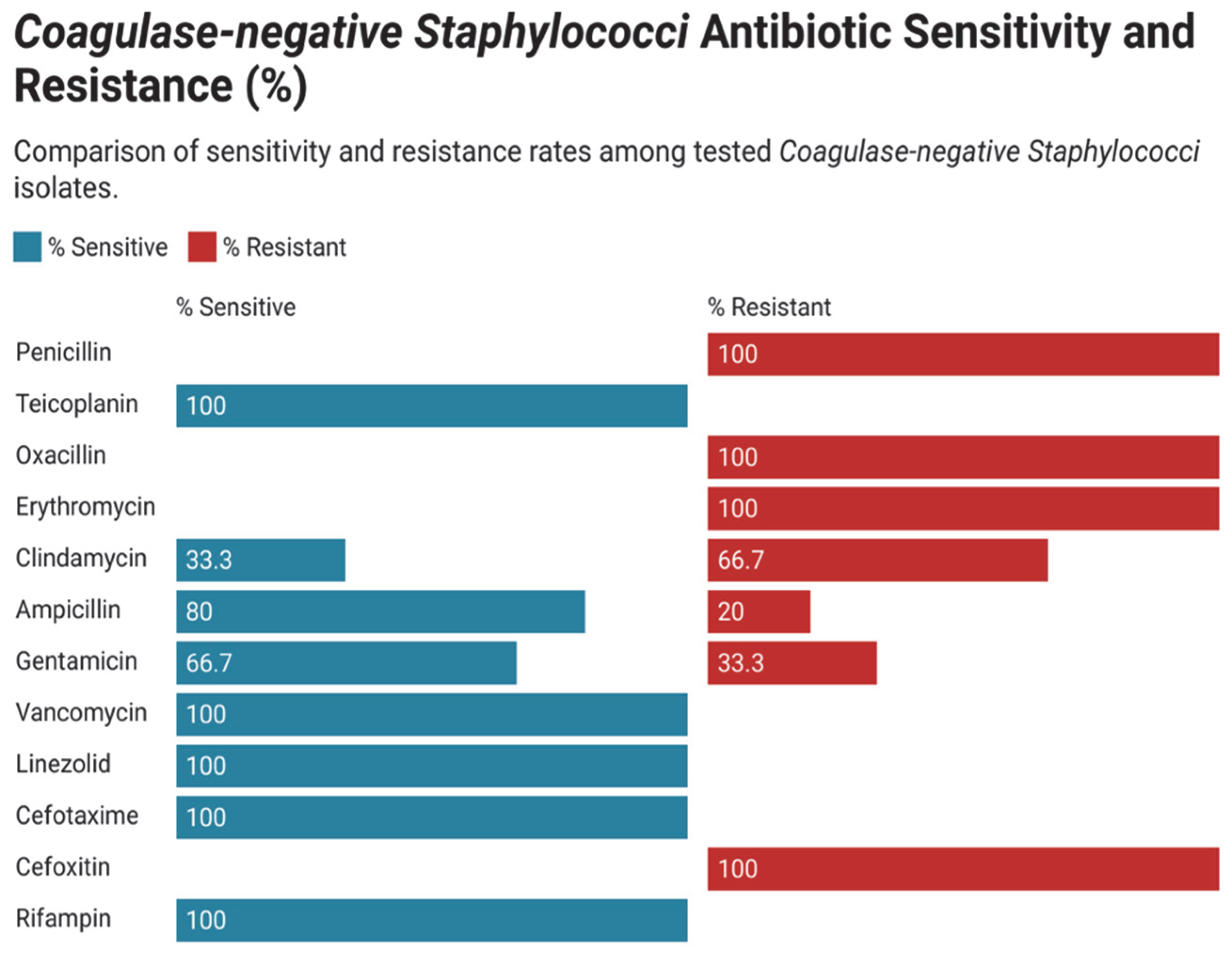

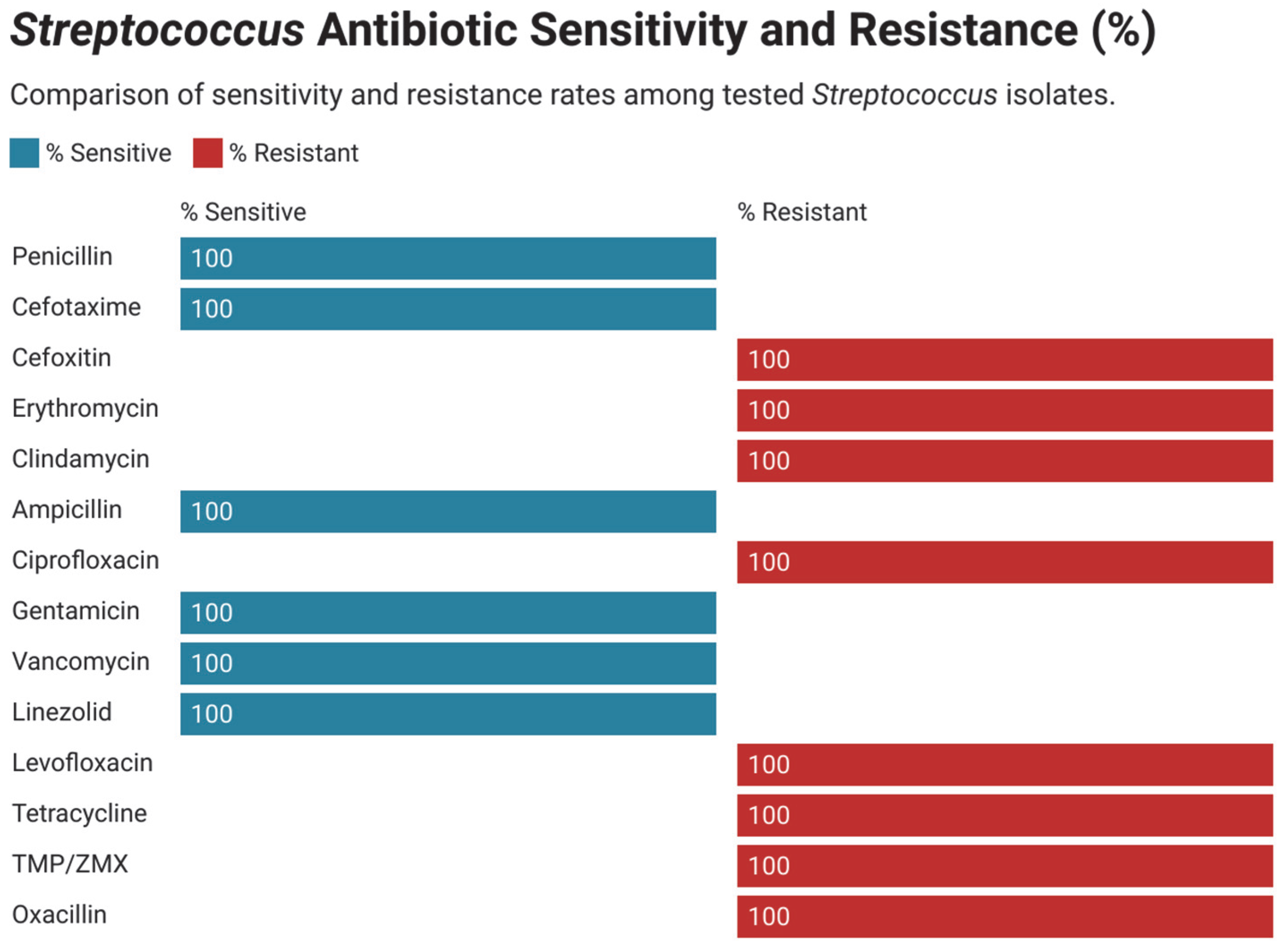

3.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Resistance Pattern in Gram-Positive Bacteria

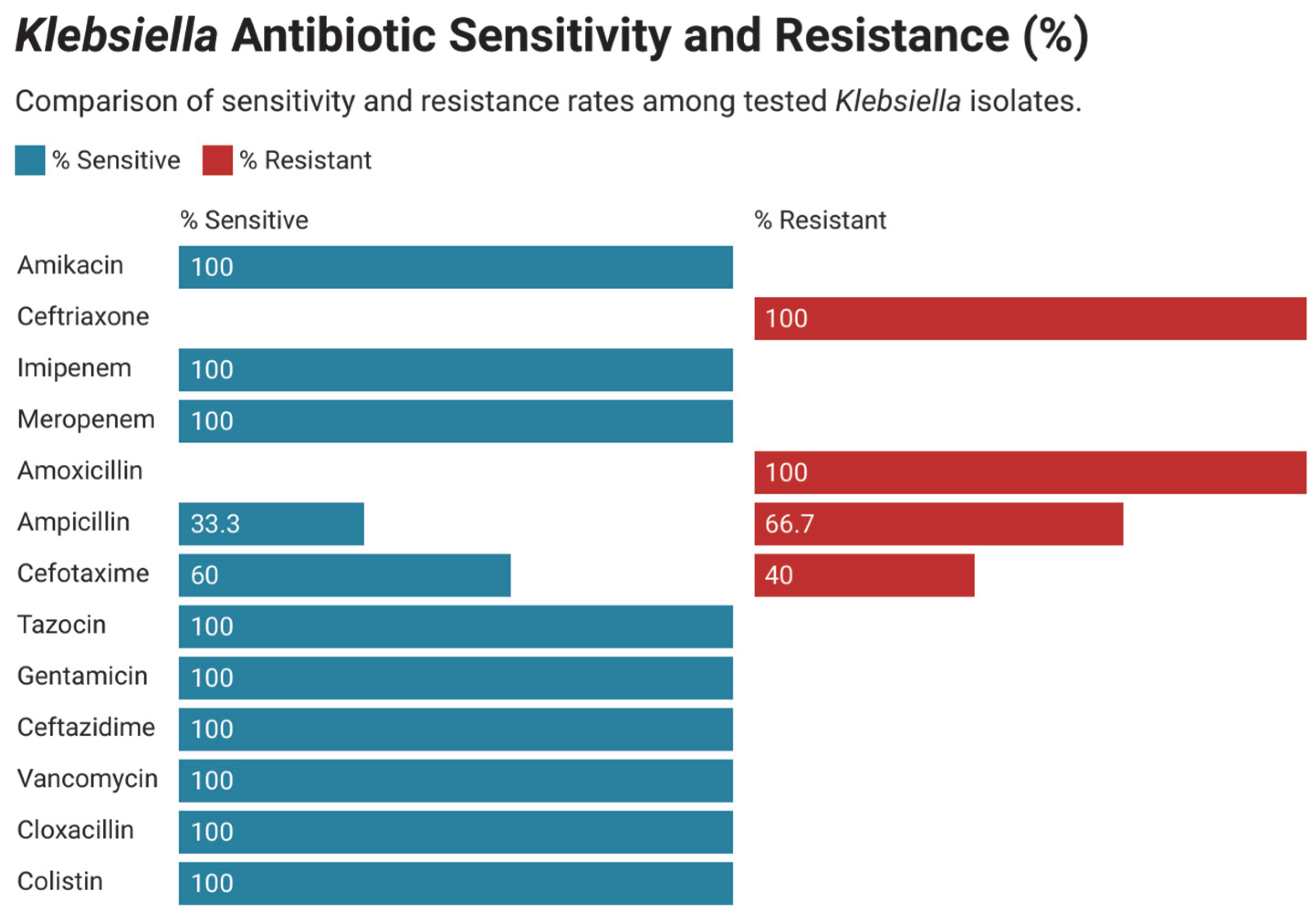

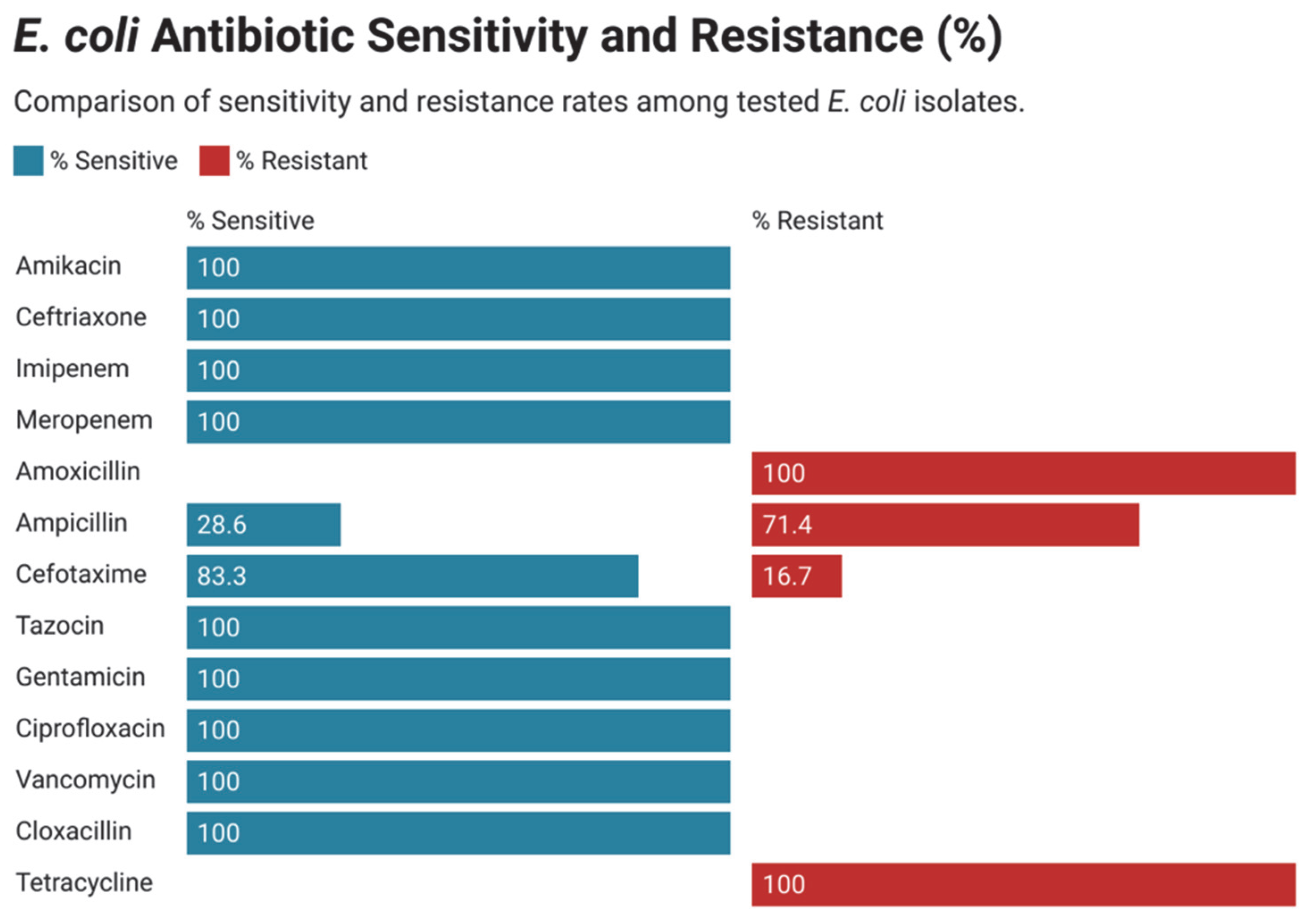

3.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Resistance Pattern in Gram-Negative Bacteria

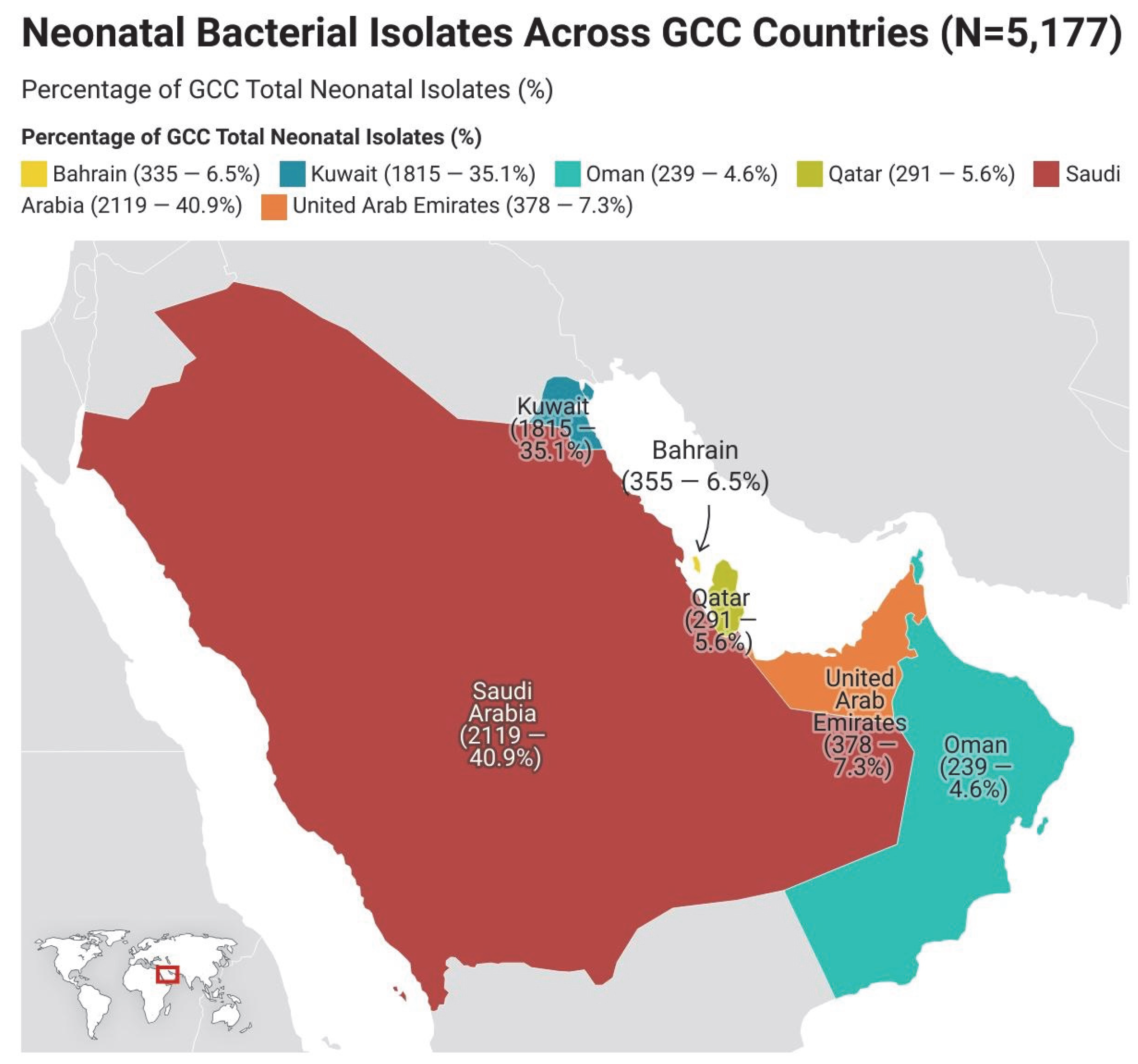

3.5. Geographical Distribution of Neonatal Isolates in the GCC Region

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levit, O.; Bhandari, V.M.; Li, F.-Y.; Shabanova, V.; Gallagher, P.G.; Bizzarro, M.J. Clinical and laboratory factors that predict death in very low birth weight infants presenting with late-onset sepsis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2014, 33, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Sepsis Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sepsis (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Mahmoud, H.A.H.; Parekh, R.; Dhandibhotla, S.; Sai, T.; Pradhan, A.; Alugula, S.; Cevallos-Cueva, M.; Hayes, B.K.; Athanti, S.; Abdin, Z.; et al. Insight into neonatal sepsis: An overview. Cureus 2023, 15, e45530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofouli, G.A.; Tsintoni, A.; Fouzas, S.; Vervenioti, A.; Gkentzi, D.; Dimitriou, G. Early diagnosis of late-onset neonatal sepsis using a sepsis prediction score. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, C.R.; Cavanagh, M.M.M.; Tembo, B.; Chiume, M.; Lufesi, N.; Goldfarb, D.M.; Kissoon, N.; Lavoie, P.M. Neonatal sepsis in low-income countries: Epidemiology, diagnosis and prevention. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, F.; Scicchitano, P.; Gesualdo, M.; Filaninno, A.; De Giorgi, E.; Schettini, F.; Laforgia, N.; Ciccone, M.M. Early and late infections in newborns: Where do we stand? A review. Pediatr. Neonatol. 2016, 57, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Wright, L.L.; Carlo, W.A.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Lemons, J.A.; Donovan, E.F.; Stark, A.R.; Tyson, J.E.; et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: The experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnano, S.; Menson, E.; Kennea, N.; Embleton, N.; Russell, A.B.; Watts, T.; Robinson, M.J.; Collinson, A.; Heath, P.T. Neonatal infections in England: The NeonIN surveillance network. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2011, 96, F9–F14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Sánchez, P.J.; Faix, R.G.; Poindexter, B.B.; Van Meurs, K.P.; Bizzarro, M.J.; Goldberg, R.N.; Frantz, I.D., III; Hale, E.C.; et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: The burden of group B streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghadeer, H.A.; Alabdallah, R.H.; AlKhalaf, G.I.; Aldandan, F.K.; Almohammed, H.A.; Al Busaeed, M.M.; Alkhawajah, F.M.; Al Hassan, K.A.; Alghadeer, F.A.; Alreqa, H.H.; et al. Characteristics and Associated Risk Factors of Neonatal Sepsis: A Retrospective Study From Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e76517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosson, A.M.S.; Speer, C.P. Microbial pathogens causative of neonatal sepsis in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2011, 32, 723–729. [Google Scholar]

- Elkersh, T.; Marie, M.A.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Al Bloushy, A.; Al-Agamy, M.H. Prevalence of fecal carriage of extended-spectrum- and metallo-β-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacteria among neonates born in a hospital setting in central Saudi Arabia. Ann. Saudi Med. 2015, 35, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanezi, G.; Almulhem, A.; Aldriwesh, M.; Bawazeer, M. A triple antimicrobial regimen for multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal intensive care unit outbreak: A case series. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarjani, K.M.; Almutairi, A.M.; AlQahtany, F.S.; Soundharrajan, I. Methicillin and multidrug resistant pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus associated sepsis in hospitalized neonatal infections and antibiotic susceptibility. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharbi, A.S. Common bacterial isolates associated with neonatal sepsis and their antimicrobial profile: A retrospective study at King Abdulaziz University Hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e21107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhai, E.E.; Alrabiaah, A.A. A review of clinically suspected sepsis and meningitis in infants under 90 days old in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. J. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 1, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moubareck, C.A.; Hammoudi Halat, D.; Sartawi, M.; Lawlor, K.; Sarkis, D.K.; Alatoom, A. Assessment of CHROMagar KPC and Xpert Carba-R for carbapenem-resistant bacteria detection in rectal swabs: First comparative study from Abu Dhabi. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 20, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, H.A.; Ismail, K.A.; Shbat, M.; AlGhathami, M.; Saber, T.; Khalifa, O.M.; Al-Malik, A.; Alqarni, R.; Alsufyani, G.; Johari, F.; et al. Identification of microorganisms causing neonatal sepsis and their antibiotic susceptibility. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2023, 12, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mouqdad, M.; Alaklobi, F.; Aljobair, F.; Alnizari, T.; Taha, M.; Asfour, S. A retrospective cohort study patient chart review of neonatal sepsis investigating responsible microorganisms and their antimicrobial susceptibility. J. Clin. Neonatol. 2018, 7, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, M.S.; Al-Taiar, A.; Al-Abdi, S.Y.; Bozaid, H.; Khan, A.; AlMuhairi, L.M.; Rehman, M.U. Late-onset neonatal sepsis in Arab states in the Gulf region: Two-year prospective study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 55, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, M.S.; Al-Taiar, A.; Fouad, M.; Raina, A.; Khan, Z. Persistent candidemia in neonatal care units: Risk factors and clinical significance. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e624–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaid, A.S.; Aldarhami, A.; Bokhary, N.A.; Bazaid, M.B.; Qusty, M.F.; AlGhamdi, T.H.; Almarashi, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors associated with drug resistant bacteria in neonatal and pediatric intensive care units: A retrospective study in Saudi Arabia. Medicine 2023, 102, e35638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Lutfi, S.; Al Hail, M.; Al Saadi, M. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of microbial isolates from blood cultures in the neonatal intensive care unit of Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2013, 6 (Suppl. 2), 191–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El Hafez, M.; Khalaf, N.G.; El Ahmady, M.; Abd El Aziz, A.; Hashim Ael, G. An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis among neonates in a hospital in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2011, 5, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mazroea, A.H. Neonatal sepsis in preterm neonates, Almadina Almunawara, Saudi Arabia, Background, Etiology. Pharmacophore 2017, 8, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogbel, M.; Altheban, A.; Alenezi, M.; Al-Motair, K.; Menezes, G.A.; Elabbasy, M.; Hammam, S.; Hays, J.P.; A Khan, M. CTX-M-15-positive Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak in the neonatal intensive care unit of a maternity hospital in Ha’il, Saudi Arabia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaleh, K.M. Incidence of late-onset neonatal sepsis in very low birth weight infants in a tertiary hospital: An ongoing challenge. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2010, 10, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kersh, T.A.; Marie, M.A.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Al-Agamy, M.H.; Al-Bloushy, A.A. Prevalence and risk factors of early fecal carriage of Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus spp. and their antimicrobial resistant patterns among healthy neonates born in a hospital setting in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2016, 37, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anazi, F.; Abdelrahman, A.; Al-Mutairi, T.; Al-Farhan, A. Colonization by group B Streptococcus and antimicrobial resistance profiles among pregnant women in Kuwait. ARC J. Public Health Community Med. 2018, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Taiar, A.; Hammoud, M.S.; Thalib, L.; Isaacs, D. Pattern and etiology of culture-proven early-onset neonatal sepsis: A five-year prospective study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 15, e631–e634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaid, A.S.; Aldarhami, A.; Gattan, H.; Barnawi, H.; Qanash, H.; Alsaif, G.; Alharbi, B.; Alrashidi, A.; Eldrehmy, E.H. Antibiogram of urinary tract infections and sepsis among infants in neonatal intensive care unit. Children 2022, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonuzi, A.; Zvizdic, Z.; Karavdić, K.; Milisic, E.; Pasic, I.S.; Mesic, A.; Kulovac, B.; Vranic, S. Adrenal abscess in a preterm neonate with sepsis. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 75, 102094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; El Amin, E. Changing patterns of blood-borne sepsis in Special Care Baby Unit, Khoula Hospital. Oman Med. J. 2010, 25, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyvilayil, S.S.; Vellamgot, A.P.; Salameh, K.; Kurunthattilthazhe, S.B.; Elikkottil, A.; Dominguez, L.L.; Banarjee, D. Incidence and outcomes of neonatal Group B Streptococcal sepsis in Qatar: A multicentre study. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawodu, A.; Al Umran, K.; Twum-Danso, K. A case control study of neonatal sepsis: Experience from Saudi Arabia. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1997, 43, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kishawi, A.; El-Emmawie, A.H.; Yehia, A.; Aly, N. Streptococcus pneumoniae as a cause of early-onset neonatal sepsis: First report from Kuwait. Kuwait Med. J. 2008, 40, 324–325. [Google Scholar]

- Mokaddas, E.M.; Shetty, S.A.; Abdullah, A.A.; Rotimi, V. A 4-year prospective study of septicemia in pediatric surgical patients at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Kuwait. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Reyami, E.; Al Zoabi, K.; Rahmani, A.; Tamim, M.; Chedid, F. Is isolation of outborn infants required at admission to the neonatal intensive care unit? Am. J. Infect. Control 2009, 37, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almudeer, A.H.; Alibrahim, M.A.; Gosadi, I.M. Epidemiology and risk factors associated with early onset neonatal sepsis in the south of KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Matary, A.; Heena, H.; AlSarheed, A.S.; Ouda, W.; AlShahrani, D.A.; Wani, T.A.; Qaraqei, M.; Abu-Shaheen, A. Characteristics of neonatal Sepsis at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAbdullatif, M.; Narchi, H.; Khan, N.; Rahmani, A.; Alkhatib, T.; Abu-Sa’da, O.; Khassawneh, M. Microbiology of neonatal Gram-negative sepsis in a Level III NICU: A single-center experience. GJPNC 2019, 1, GJPNC.MS.ID.000519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, M.A.; Omer, A.F.A.; Asaif, S.; Manlulu, R.; Karar, T.; Ahmed, A.; Aljada, A.; Saleh, A.M.; Qureshi, S.; Nasr, A. Utility of cytokine, adhesion molecule and acute phase proteins in early diagnosis of neonatal sepsis. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2017, 8, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masroori, E.A.; Uraba, W.B.; Al Hashami, H. Incidence and outcome of group B streptococcal invasive disease in Omani infants. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2020, 7, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrafiaah, A.S.; AlShaalan, M.; Alshammari, F.O.; Almohaisani, A.A.; Bawazir, A.S.; Omair, A. Neonatal sepsis in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zahrani, A.K.; Ghonaim, M.M.; Hussein, Y.M.; Eed, E.M.; Khalifa, A.S.; Dorgham, L.S. Evaluation of recent methods versus conventional methods for diagnosis of early-onset neonatal sepsis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Essa, M.; Khan, Z.; Rashwan, N.; Kazi, A. Pattern of candidiasis in the newborn: A study from Kuwait. Med. Princ. Pract. 2000, 9, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Ahmad, S.; Al-Sweih, N.; Khan, S.; Joseph, L. Candida lusitaniae in Kuwait: Prevalence, antifungal susceptibility and role in neonatal fungemia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Srair, H.; Owa, J.A.; El-Bashier, A.M.; Aman, H. Genital flora, prolonged rupture of the membranes and the risk of early onset neonatal septicemia in Qatif Central Hospital, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Early Child Dev. Care 1993, 93, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindayna, K.M.; Jamsheer, A.; Farid, E.; Botta, G.A. Neonatal sepsis 1991–2001: Prevalent bacterial agents and antimicrobial susceptibilities in Bahrain. Med. Princ. Pract. 2006, 15, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asindi, A.A.; Bilal, N.; Fatinni, Y.A.; Habeeb, S.M. Neonatal septicemia. Saudi Med. J. 1999, 20, 942–946. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson, A.; Bailey, T.; Takieddine, F. Changing etiology and outcome of neonatal septicemia in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1986, 75, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashier, A.M.; Abusrair, H.; Owa, J.A. Aetiology of neonatal septicaemia in Qatif, Saudi Arabia. Early Child Dev. Care 1994, 98, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutouby, A.; Habibullah, J. Neonatal sepsis in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1995, 41, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khater, E.S.; Al-Hosiny, T.M.; Taha, M. Presepsin as a new marker for early detection of neonatal sepsis in Al-Quwayiyah General Hospital, Riyadh, KSA. J. Adv. Microbiol. 2020, 20, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abdellatif, M.; Al-Khabori, M.; Ur Rahman, A.; Khan, A.A.; Al-Farsi, A.; Ali, K. Outcome of late-onset neonatal sepsis at a tertiary hospital in Oman. Oman Med. J. 2019, 34, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammoud, M.S.; Al-Taiar, A.; Thalib, L.; Al-Sweih, N.; Pathan, S.; Isaacs, D. Incidence, aetiology and resistance of late-onset neonatal sepsis: A five-year prospective study. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 48, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haqan, A.; Boswihi, S.S.; Pathan, S.; Udo, E.E. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence determinants in coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated mainly from preterm neonates. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZuheiri, S.T.S.; Dube, R.; Menezes, G.; Qasem, S. Clinical profile and outcome of group B Streptococcal colonization in mothers and neonates in Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates: A prospective observational study. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shittu, S.A.; Athar, S.; Shaukat, A.; Alansari, L. Chorioamnionitis and neonatal sepsis due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection: A case report. Clin. Case Rep. 2021, 9, e05078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Mannaei, L.; Al-Saad, I.Y.; Al Saadon, E. Neonatal sepsis: A two-year review of the antibiograms of clinical isolates from the neonatal unit. Bahrain Med. Bull. 2017, 39, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Sweih, N.; Jamal, M.; Kurdia, M.; Abduljabar, R.; Rotimi, V. Antibiotic susceptibility profile of group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae) at the Maternity Hospital, Kuwait. Med. Princ. Pract. 2005, 14, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sweih, N.; Khan, Z.; Khan, S.; Devarajan, L.V. Neonatal candidaemia in Kuwait: A 12-year study of risk factors, species spectrum and antifungal susceptibility. Mycoses 2009, 52, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kersh, T.A.; Neyazi, S.M.; Al-Sheikh, Y.A.; Niazy, A.A. Phenotypic traits and comparative detection methods of vaginal carriage of group B streptococci and associated microbiota in term pregnant Saudi women. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 6, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.M.; Khan, M.A.; Faiz, A.; Ahmad, J.; Khidir, E.B.; Basalamah, M.A.; Aslam, A. Group B streptococcus colonization, antibiotic susceptibility, and serotype distribution among Saudi pregnant women. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 52, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutairi, F.; Al-Mutairi, A.; Al-Enezi, M.; Al-Harbi, T.; Al-Shammari, R. Colonization by group B Streptococcus and antimicrobial resistance patterns in Kuwait: An observational study in 2014 and 2016. ARC J. Public Health Community Med. 2018, 3, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Elessawy, F.M. Development and Fertility Decline in the Arabian Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: The Case of the United Arab Emirates. Arab World Geogr. 2023, 26, 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo, K.M.; Lynfield, R.; Cummings, J.J.; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases; Hand, I.; Adams-Chapman, I.; Poindexter, B.; Stewart, D.L.; Aucott, S.W.; et al. Management of Infants at Risk for Group B Streptococcal Disease. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20191881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, T.; Zell, E.R.; Schrag, S. Effectiveness of Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Prevention of Early-Onset Group B Streptococcal Disease. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 121, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jihwaprani, M.C.; Sula, I.; Coha, D.; Alhebshi, A.; Alsamal, M.; Hassaneen, A.M.; Alreshidi, M.A.; Saquib, N. Bacterial Profile and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of Common Neonatal Sepsis Pathogens in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Qatar Med. J. 2024, 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, N.; Blunt, H.B.; Li, Z.; Hartman, T. Neonatal Early Onset Sepsis in Middle Eastern Countries: A Systematic Review. Arch. Dis. Child. 2020, 105, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.G.; Benjamin, D.K. Neonatal Candidiasis: Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Infect. 2014, 69 (Suppl. S1), S19–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariniotaki, C.; Thomou, C.; Gkentzi, D.; Panteris, E.; Dimitriou, G.; Hatzidaki, E. Neonatal Sepsis: A Comprehensive Review. Antibiotics 2024, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokou, R.; Palioura, A.E.; Kopanou Taliaka, P.; Konstantinidi, A.; Tsantes, A.G.; Piovani, D.; Tsante, K.A.; Gounari, E.A.; Iliodromiti, Z.; Boutsikou, T.; et al. Candida Auris Infection, a Rapidly Emerging Threat in the Neonatal Intensive Care Units: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi-Hoffnung, L.; Rosenberg Danziger, C. Navigating the New Reality: A Review of the Epidemiological, Clinical, and Microbiological Characteristics of Candida Auris, with a Focus on Children. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiantzi, G.; Metallinou, D.; Tigka, M.; Deltsidou, A.; Nanou, C.I. Bloodstream Infections in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e68057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UpToDate. Neonatal Bacterial Sepsis: Clinical Features and Diagnosis in Neonates ≥35 Weeks Gestation—Medline® Abstract for Reference 6. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neonatal-bacterial-sepsis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis-in-neonates-35-weeks-gestation/abstract/6 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Stocker, M.; Rosa-Mangeret, F.; Agyeman, P.K.A.; McDougall, J.; Berger, C.; Giannoni, E. Management of neonates at risk of early onset sepsis: A probability-based approach and recent literature appraisal. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 5517–5529. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00431-024-05811-0 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puopolo, K.M.; Benitz, W.E.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases; Cummings, J.; Juul, S.; Hand, I.; Eichenwald, E.; Poindexter, B.; et al. Management of neonates born at ≤34 6/7 weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puopolo, K.M.; Benitz, W.E.; Zaoutis, T.E.; Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Committee on Infectious Diseases; Cummings, J.; Juul, S.; Hand, I.; Eichenwald, E.; Poindexter, B.; et al. Management of neonates born at ≥35 0/7 weeks’ gestation with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia NICU. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Onset Neonatal Sepsis. 2024. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Documents/NICU_DIAGNOSIS_and_MANAGEMENT_GUIDELINES_of_EOS.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwidtdPo2MWQAxXp1jgGHYO0BGEQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1HlkwxRG-2Pm-YqGcIL8_3 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Hope, W.W.; Castagnola, E.; Groll, A.H.; Roilides, E.; Akova, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Bassetti, M.; Bille, J.; Cornely, O.A.; et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: Prevention and management of invasive infections in neonates and children caused by Candida spp. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18 (Suppl. S7), 38–52. Available online: https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/action/showFullText?pii=S1198743X14607667 (accessed on 15 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Labib, A.; Ashour, R. Qatar National Paediatric Sepsis Program: Where are we? Qatar Med. J. 2019, 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Regulatory Authority, Kingdom of Bahrain. National Perinatal Practice Guideline for Perinatal Care of Extremely Preterm Baby at The Threshold of Viability. Available online: https://www.nhra.bh/Departments/HCP/guidelines/MediaHandler/GenericHandler/documents/departments/HCP/guidelines/National%20Perinatal%20Practice%20Guidlines%20V1.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Gomaa, H.A.; Udo, E.E.; Rajaram, U. Neonatal Septicemia in Al-Jahra Hospital, Kuwait: Etiologic Agents and Antibiotic Sensitivity Patterns. Med. Princ. Pract. 1998, 7, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health Abu Dhabi. DOH Standard for Provision of Neonatal Care Services in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi. Available online: https://www.doh.gov.ae/-/media/55EAB022402C4CB2A02A4867673B34FB.ashx (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Amer, Y.S.; Shaiba, L.A.; Hadid, A.; Anabrees, J.; Almehery, A.; Aassiri, M.; Alnemri, A.; Al Darwish, A.R.; Baqawi, B.; Aboshaiqah, A.; et al. Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for neonatal sepsis using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II Instrument: A systematic re-view of neonatal guidelines. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 891572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, B.; Abdel-Razig, S. Design and Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Certificate Program in the United Arab Emirates. Int. Med. Educ. 2023, 2, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, F.I.; Saad, T.; Zakhour, R.; Yunis, K. Successful establishment and five-year sustainability of a neonatal-specific antimicrobial stewardship program in a low-middle-income country. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1076392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhalik, M.; Al-Turkistani, H.; Al-Harbi, A.; Al-Enazi, S.; Al-Shehri, S. Epidemiology of sepsis in NICU: A 12 years study from Dubai, UAE. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Care 2018, 8, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anwer, R.; Al-shehri, H.; Alsulami, M.; Alsulami, Z.; Alzkari, F.; Alshaalan, N.; Almutairi, N.; Albalawi, A.S.; Alshammari, K.; Alshehri, A.F.; et al. Pathogen Profiles and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Neonatal Sepsis in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Systematic Review. Children 2025, 12, 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111475

Anwer R, Al-shehri H, Alsulami M, Alsulami Z, Alzkari F, Alshaalan N, Almutairi N, Albalawi AS, Alshammari K, Alshehri AF, et al. Pathogen Profiles and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Neonatal Sepsis in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Systematic Review. Children. 2025; 12(11):1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111475

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnwer, Razique, Hassan Al-shehri, Musab Alsulami, Ziyad Alsulami, Faisal Alzkari, Nawaf Alshaalan, Nawaf Almutairi, Abdullah Saleh Albalawi, Khalid Alshammari, Abdulelah F. Alshehri, and et al. 2025. "Pathogen Profiles and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Neonatal Sepsis in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Systematic Review" Children 12, no. 11: 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111475

APA StyleAnwer, R., Al-shehri, H., Alsulami, M., Alsulami, Z., Alzkari, F., Alshaalan, N., Almutairi, N., Albalawi, A. S., Alshammari, K., Alshehri, A. F., Alzahrani, N., Alamer, I. A., Alotaibi, A., & Alzakari, M. (2025). Pathogen Profiles and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Neonatal Sepsis in the Gulf Cooperation Council: A Systematic Review. Children, 12(11), 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111475