QEEG-Guided rTMS in Pediatric ASD with Contextual Evidence on Home-Based tDCS: Within-Cohort Reanalysis and Narrative Contextualization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Design

2.1. Participants (rTMS Cohort)

2.2. QEEG Acquisition and Target Identification

2.3. Intervention (rTMS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis (rTMS)

2.5. Contextualisation of tDCS Evidence

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics (rTMS)

3.2. Behavioural Outcomes (rTMS)

3.3. Neurophysiological Outcomes (rTMS)

3.4. QEEG Analyses Revealed Significant Normalisation of Prefrontal Oscillatory Activity

- β/γ power: Decreased 18.5% (Cohen’s d = −1.04).

- α power: Increased 19.7% (d = 0.81).

- θ/α ratio: Decreased 15.5% (d = −1.63).

- δ and θ slow waves: Reduced 17–30% across frontolateral sites (all d > −1.4).

3.5. Safety and Feasibility (rTMS)

- Adverse events: No serious adverse events were reported. Minor, transient side effects included headache (3.6% of participants) and mild fatigue (<2% of sessions). Such mild and transient side effects are consistent with findings from other rTMS studies, further supporting its favorable safety profile in adolescent populations [54].

- Adherence: Median completion was 39 of 40 sessions (98%). This high adherence rate indicates the acceptability and tolerability of the intervention within the paediatric population. Such high adherence, even with multiple sessions, highlights the importance of patient and caregiver engagement in non-invasive neuromodulation therapies, especially for chronic conditions like ASD.

- Caregiver acceptability: On a 5-point Likert scale, mean rating was 4.5 (n = 46 respondents). This high level of caregiver satisfaction underscores the practical utility and perceived benefit of rTMS in managing ASD symptoms, facilitating treatment uptake and sustained engagement [33,55]. In addition, caregiver reports from semi-structured interviews frequently highlight improvements in comorbid conditions such as sleep disturbances, further enhancing treatment satisfaction [32]. These improvements in ancillary symptoms contribute significantly to the overall quality of life for both the child and family, extending beyond the primary targeted ASD symptoms. The demonstrated safety and efficacy of rTMS in pediatric ASD, along with high adherence and caregiver satisfaction, underscore its potential as a critical component in comprehensive treatment plans [31,48]. Further research, however, is warranted to investigate long-term outcomes, optimal stimulation parameters, and the potential for combination therapies to maximize therapeutic benefits and achieve sustained symptom reduction in this vulnerable population [25].

3.6. Contextual Evidence (tDCS; Narrative Summary)

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Several Critical Limitations Restrict Interpretation

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbeduto, L.; Şahin, M. Developing and evaluating treatments for the challenges of autism and related neurodevelopmental disabilities. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mews, P.; Kenny, P.J.; Paulus, M.P.; Steinglass, J.; Berner, L.A.; Stern, S.A.; Rodriguez, C.; Chavez, M.; Gilmore, J.V.; Pergola, G.; et al. ACNP 62nd Annual Meeting: Panels, Mini-Panels and Study Groups. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moxon-Emre, I.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Blumberger, D.M.; Croarkin, P.E.; Forde, N.J.; Tani, H.; Truong, P.; Lai, M.; Desarkar, P.; Sailasuta, N.; et al. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Modulates Glutamate/Glutamine Levels in Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, S331–S332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.C.; Sousa, D.; Simões, M.; Martins, R.; Amaral, C.; Lopes, V.; Crisóstomo, J.; Castelo-Branco, M. Effects of anodal multichannel transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on social-cognitive performance in healthy subjects: A randomized sham-controlled crossover pilot study. Prog. Brain Res. 2021, 264, 259–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandran, N.G.; Hillier, S.; Hordacre, B. Strategies to implement and monitor in-home transcranial electrical stimulation in neurological and psychiatric patient populations: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannar, E.M.; Winter, J.R.; Franke, R.K.; Werner, E.; Rochowiak, R.; Romani, P.W.; Miller, O.S.; Bainbridge, J.; Enabulele, O.; Thompson, T.; et al. Cannabidiol for treatment of Irritability and Aggressive Behavior in Children and Adolescents with ASD: Background and Methods of the CAnnabidiol Study in Children with Autism Spectrum DisordEr (CASCADE) Study. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheerer, N.E.; Curcin, K.; Stojanoski, B.; Anagnostou, E.; Nicolson, R.; Kelley, E.; Georgiades, S.; Liu, X.; Stevenson, R.A. Exploring sensory phenotypes in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.; Smith, E.G.; Pedapati, E.V.; Horn, P.S.; Will, M.; Lamy, M.; Barber, L.; Trebley, J.; Meyer, K.; Heiman, M.; et al. Results of a phase Ib study of SB-121, an investigational probiotic formulation, in participants with autism spectrum disorder. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, R.A.; Rippon, G.; Gooding-Williams, G.; Sowman, P.F.; Kessler, K. Reduced auditory steady state responses in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 2020, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splittgerber, M.; Borzikowsky, C.; Salvador, R.; Puonti, O.; Papadimitriou, K.; Merschformann, C.; Biagi, M.C.; Stenner, T.; Brauer, H.; Breitling-Ziegler, C.; et al. Multichannel anodal tDCS over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in a paediatric population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Steenburgh, J.J.; Varvaris, M.; Schretlen, D.J.; Vannorsdall, T.D.; Gordon, B. Balanced bifrontal transcranial direct current stimulation enhances working memory in adults with high-functioning autism: A sham-controlled crossover study. Mol. Autism 2017, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Wang, B.; Wei, Z.; Feng, Z.; Wu, Z.-L.; Yassin, W.; Stone, W.S.; Lin, Y.; Kong, X. Identification of diagnostic markers for ASD: A restrictive interest analysis based on EEG combined with eye tracking. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1236637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoen, A.; Steyaert, J.; Alaerts, K.; Damme, T.V. Evaluating the potential of respiratory-sinus-arrhythmia biofeedback for reducing physiological stress in adolescents with autism: A protocol for a randomized controlled study. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, S.J.; Criaud, M.; Lam, S.-L.; Lukito, S.; Wallace-Hanlon, S.; Kowalczyk, O.S.; Kostara, A.; Mathew, J.P.; Agbedjro, D.; Wexler, B.E.; et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with cognitive training in adolescent boys with ADHD: A double-blind, randomised, sham-controlled trial. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-J.; Huang, C.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chang, A.Y.; Wang, W.-C.; Lin, C.K. The distinct and potentially conflicting effects of tDCS and tRNS on brain connectivity, cortical inhibition, and visuospatial memory. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1415904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.; Kang, J.; Ouyang, G.; Li, J.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Sokhadze, E.M.; Casanova, M.F.; Li, X. Disrupted Brain Network in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, E.Z.; Wong, N.M.L.; Yang, A.S.Y.; Lee, T.M.C. Evaluating the effects of tDCS on depressive and anxiety symptoms from a transdiagnostic perspective: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, L.A.; Pergola, G.; Dwyer, D.; Torretta, S.; Romano, R.; Gelao, B.; Penzel, N.; Rampino, A.; Masellis, R.; Caforio, G.; et al. O5. Classification of Schizophrenia Using Machine Learning With Multimodal Markers. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 85, S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachor, D.A.; Ben-Itzchak, E. From toddlerhood to adolescence, trajectories and predictors of outcome: Long-term follow-up study in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2020, 13, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billstedt, E.; Gillberg, I.C.; Gillberg, C. Autism in adults: Symptom patterns and early childhood predictors. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubonnet, R.; Banea, O.C.; Sirica, R.; Wassermann, E.M.; Yassine, S.; Jacob, D.; Magnúsdóttir, B.B.; Haraldsson, M.; Stefánsson, S.B.; Jónasson, V.D.; et al. P300 Analysis Using High-Density EEG to Decipher Neural Response to rTMS in Patients With Schizophrenia and Auditory Verbal Hallucinations. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 575538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailar-Heath, M.; Burke, R.; Thomas, D.; Morrow, C.D. A retrospective chart review to assess the impact of alpha-guided transcranial magnetic stimulation on symptoms of PTSD and depression in active-duty special operations service members. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1354763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Veytsman, E.; Choy, T.; Blacher, J.; Stavropoulos, K.K.M. Investigating Changes in Reward-Related Neural Correlates After PEERS Intervention in Adolescents With ASD: Preliminary Evidence of a “Precision Medicine” Approach. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 742280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billeci, L.; Sicca, F.; Maharatna, K.; Apicella, F.; Narzisi, A.; Campatelli, G.; Calderoni, S.; Pioggia, G.; Muratori, F. On the Application of Quantitative EEG for Characterizing Autistic Brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, M.F.; Sokhadze, E.M.; Casanova, M.; Li, X. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Neuropathological Underpinnings and Clinical Correlations. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 35, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, B.; Hunter, S.; Cottrell, H.; Dar, R.; Takahashi, N.; Ferguson, B.J.; Valter, Y.; Porges, E.C.; Datta, A.; Beversdorf, D.Q. Remotely supervised at-home delivery of taVNS for autism spectrum disorder: Feasibility and initial efficacy. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1238328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camsari, D.D.; Kirkovski, M.; Croarkin, P.E. Therapeutic Applications of Noninvasive Neuromodulation in Children and Adolescents. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 41, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.M.Y.; Choi, C.X.T.; Tsoi, T.C.W.; Shea, C.K.; Yiu, K.W.K.; Han, Y.M.Y. Effects of multisession cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation with cognitive training on sociocognitive functioning and brain dynamics in autism: A double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized EEG study. Brain Stimul. 2023, 16, 1604–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.; Enticott, P.G.; Oberman, L.M.; Gwynette, M.F.; Casanova, M.F.; Jackson, S.L.J.; Jannati, A.; McPartland, J.C.; Naples, A.; Puts, N.A.J.; et al. The Potential of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Consensus Statement. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 85, e21–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B.A.; Key, A.P.; Klemencic, M.E.; Muscatello, R.A.; Jones, D.; Pilkington, J.; Burroughs, C.; Vandekar, S. Investigating Social Competence in a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial of a Theatre-Based Intervention Enhanced for Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disorders 2023, 55, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croarkin, P.E.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Deng, Z.; Romanowicz, M.; Voort, J.L.V.; Camsari, D.D.; Schak, K.M.; Port, J.D.; Lewis, C.P. High-frequency repetitive TMS for suicidal ideation in adolescents with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, X.; Ji, Y.; Wang, K.; Du, X.; Liu, X.; Tang, Y.; Deng, S.; et al. Improved symptoms following bumetanide treatment in children aged 3 to 6 years with autism spectrum disorder via GABAergic mechanisms: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; He, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, L.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ren, T.; Zhang, L.; Gong, J.; et al. Caregiver-child interaction as an effective tool for identifying autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from EEG analysis. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallop, L.; Westwood, S.J.; Hemmings, A.; Lewis, Y.D.; Campbell, I.C.; Schmidt, U. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children and young people with psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 34, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Tan, S.; Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. Impaired effective functional connectivity in the social preference of children with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1391191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desarkar, P.; Vicario, C.M.; Soltanlou, M. Non-invasive brain stimulation in research and therapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, P.; Moreno, S.; Croarkin, P.E.; Blumberger, D.M.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Farzan, F. Baseline markers of cortical excitation and inhibition predict response to theta burst stimulation treatment for youth depression. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C.; Dickinson, A.; Baker, E.; Jeste, S. EEG data collection in children with ASD: The role of state in data quality and spectral power. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2018, 57, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Toscano, E.; Sanges, V.; Sauvaget, A.; Sheffer, C.E.; Riccio, M.P.; Ferrucci, R.; Iasevoli, F.; Priori, A.; Bravaccio, C.; et al. Cerebellar Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study on Efficacy, Feasibility, Safety, and Unexpected Outcomes in Tic Disorder and Epilepsy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezedinma, U.; Swierkowski, P.; Fjaagesund, S. Outcomes from Individual Alpha Frequency Guided Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder—A Retrospective Chart Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 55, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, S.; Lugo-Marín, J.; Setién-Ramos, I.; Gisbert-Gustemps, L.; Arteaga-Henríquez, G.; Villoria, E.D.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A. Transcranial direct current stimulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 48, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzadzinski, R.; Janvier, D.; Kim, S.H. Recent Developments in Treatment Outcome Measures for Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2020, 34, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, A.; Ryan, M.A.; Block, G.; Kayarian, F.; Oberman, L.M.; Rotenberg, A.; Pascual-Leone, Á. Modulation of motor cortical excitability by continuous theta-burst stimulation in adults with autism spectrum disorder: The roles of BDNF and APOE polymorphisms. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Chen, T.; Huang, Y.; Huang, X. Effect analysis of repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with fluoxetine in the treatment of first-episode adolescent depression. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1397706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billeci, L.; Tonacci, A.; Tartarisco, G.; Narzisi, A.; Di Palma, S.; Corda, D.; Baldus, G.; Cruciani, F.; Anzalone, S.; Calderoni, S.; et al. An Integrated Approach for the Monitoring of Brain and Autonomic Response of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders during Treatment by Wearable Technologies. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jugunta, S.B.; El-Ebiary, Y.A.B.; Saravanan, K.; Prasad, K.S.R.; Koteswari, S.; Rachapudi, V.; Rengarajan, M. Unleashing the Potential of Artificial Bee Colony Optimized RNN-Bi-LSTM for Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariminezhad, S.; Zomorrodi, R.; Zrenner, C.; Blumberger, D.M.; Ameis, S.H.; Lin, H.; Lai, M.; Rajji, T.K.; Lunsky, Y.; Sanches, M.; et al. Assessing Plasticity in the Primary Sensory Cortex and Its Relation with Atypical Tactile Reactivity in Autism: A TMS-EEG Protocol. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, V.; Vashi, N.; Roudbarani, F.; Modica, P.T.; Pouyandeh, A.; Sellitto, T.; Ibrahim, A.; Ameis, S.H.; Elkader, A.; Gray, K.M.; et al. Utility of a virtual small group cognitive behaviour program for autistic children during the pandemic: Evidence from a community-based implementation study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimović, S.; Jeličić, L.; Marisavljević, M.; Fatić, S.; Gavrilović, A.; Subotić, M. Can EEG Correlates Predict Treatment Efficacy in Children with Overlapping ASD and SLI Symptoms: A Case Report. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljevic, A.; Hoath, K.; Leggett, K.; Hennessy, L.A.; Boax, C.A.; Hryniewicki, J.; Rodger, J. A naturalistic study of the efficacy and acceptability of rTMS in treating major depressive disorder in Australian youth. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulraney, M.; de Silva, U.; Joseph, A.; Fialho, M.d.L.S.; Dutia, I.; Munro, N.; Payne, J.M.; Banaschewski, T.; de Lima, C.B.; Bellgrove, M.A.; et al. International Consensus on Standard Outcome Measures for Neurodevelopmental Disorders. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2416760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narzisi, A.; Alonso-Esteban, Y.; Masi, G.; Marín, F.A. Research-Based Intervention (RBI) for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Looking beyond Traditional Models and Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials. Children 2022, 9, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhaus, E.; Lowry, S.; Santhosh, M.; Kresse, A.; Edwards, L.A.; Keller, J.; Libsack, E.J.; Kang, V.Y.; Naples, A.; Jack, A.; et al. Resting state EEG in youth with ASD: Age, sex, and relation to phenotype. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, C.; Vestring, S.; Domschke, K.; Bischofberger, J.; Serchov, T. ACNP 61st Annual Meeting: Poster Abstracts P271-P540. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022, 47, 220–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passarello, N.; Tarantino, V.; Chirico, A.; Menghini, D.; Costanzo, F.; Sorrentino, P.; Fucà, E.; Gigliotta, O.; Alivernini, F.; Oliveri, M.; et al. Sensory Processing Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Taking Stock of Assessment and Novel Therapeutic Tools. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, K.; Wu, G.; Banks-Word, K.; Rosenberger, R. An Open-Label Case Series of Glutathione Use for Symptomatic Management in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wang, H.; Ning, W.; Cui, M.; Wang, Q. New advances in the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, S.; Kadlaskar, G.; Edmondson, D.A.; Keehn, R.M.; Dydak, U.; Keehn, B. Associations between sensory processing and electrophysiological and neurochemical measures in children with ASD: An EEG-MRS study. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitsika, V.; Sharpley, C.F. Current Status of Psychopharmacological, Neuromodulation, and Oxytocin Treatments for Autism: Implications for Clinical Practice. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2023, 8, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Sweeney, J.A.; Jones, S.R. Editorial: Biomarkers to Enable Therapeutics Development in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 616641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajda, P.; Sun, X.; Doose, J.; Faller, J.; McIntosh, J.R.; Saber, G.; Huffman, S.; Pantazatos, S.P.; Yuan, H.; Goldman, R.I.; et al. Biomarkers predict the efficacy of closed-loop rTMS treatment for refractory depression. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | QEEG-Guided rTMS Cohort (n = 56) | Home-Based tDCS Cohort (n = 265, Published) | Notes/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.4 ± 2.8 (range 6–17) | ~10.2 ± 3.6 (range 6–18) * | tDCS age estimated from aggregated bands |

| Sex (M:F) | 40:16 (71% male) | Not systematically reported † | Male predominance (~3–4:1) expected epidemiologically |

| Baseline SRS-2 (T-score) | 76.3 ± 9.2 (severe range) | Collected, but baseline mean not reported | Prevents harmonised severity matching |

| Baseline ABC (Total) | 45.7 ± 8.0 | Collected, not reported | — |

| Baseline RBS-R (Total) | 34.5 ± 6.5 | Collected, not reported | — |

| Inclusion Criteria | DSM-5/ADOS-2 confirmed ASD; stable medication ≥4 weeks; QEEG screening to exclude epileptiform activity | DSM-5 confirmed ASD; IQ ≥ 50; stable medication ≥3 months | rTMS more narrowly defined |

| Exclusion Criteria | Active epilepsy; metal implants; severe ID; major comorbidities | Severe ID; epilepsy; unstable medical conditions | — |

| Recruitment Settings | Hospital neurology clinics; neurodevelopment centres; special education schools | Multi-site paediatric clinics; neurodevelopment centres; schools | — |

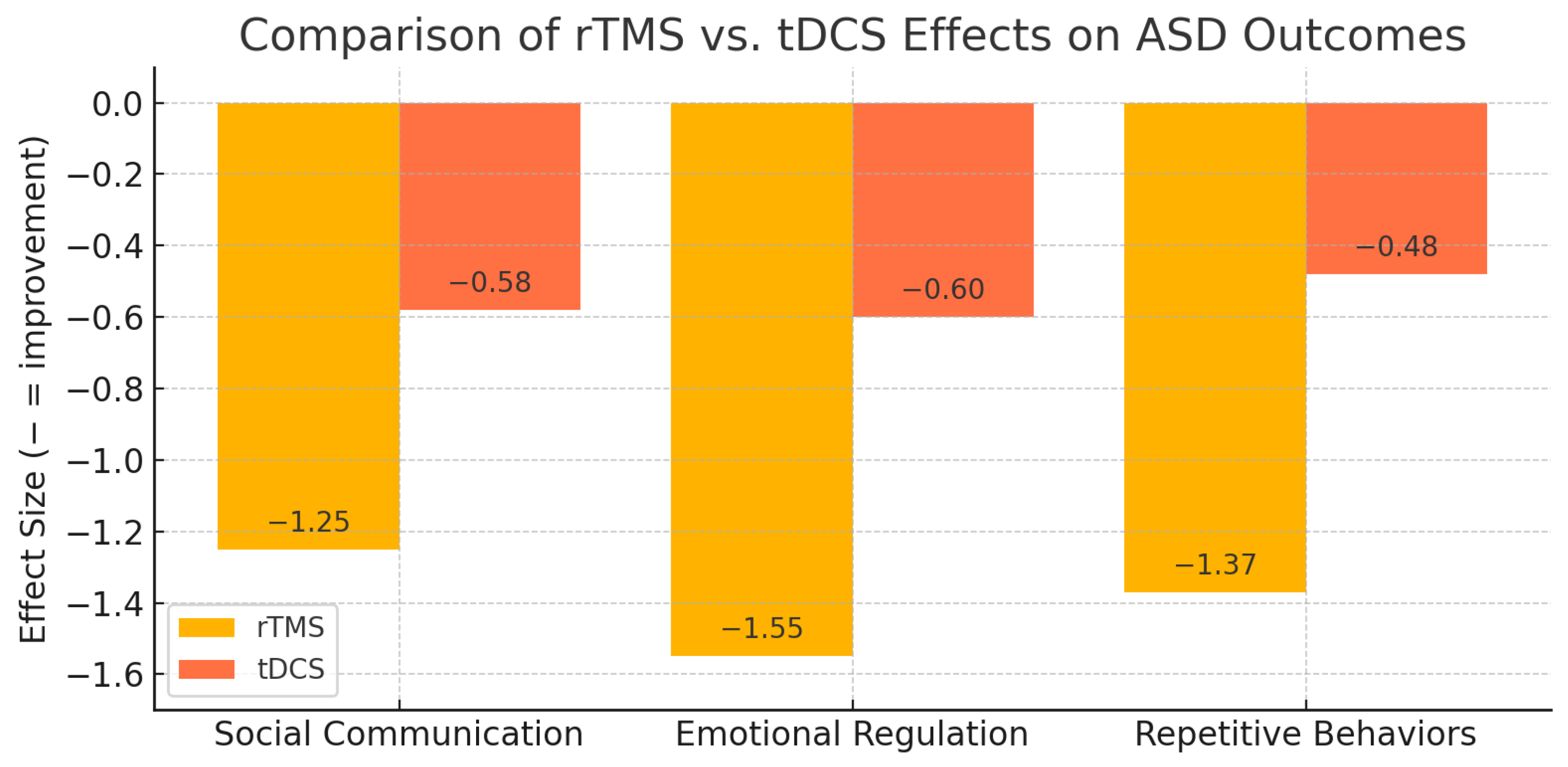

| Instrument | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Post-Treatment (Mean ± SD) | Change (Δ) | Effect Size (Hedges’ g, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRS-2 (T-score) | 76.3 ± 9.2 | 65.1 ± 8.6 | −11.2 | −1.25 (−1.56 to −0.94) |

| ADOS-2 (Total score) | 18.5 ± 4.3 | 14.2 ± 3.9 | −4.3 | −0.99 (−1.28 to −0.70) |

| ABC (Total score) | 45.7 ± 8.0 | 33.4 ± 7.5 | −12.3 | −1.55 (−1.89 to −1.21) |

| RBS-R (Total score) | 34.5 ± 6.5 | 25.8 ± 6.2 | −8.7 | −1.37 (−1.68 to −1.06) |

| Neurophysiological Parameter | Baseline Status | Post-Treatment Status | % Change | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β/γ Power (Left DLPFC) | Elevated | Reduced | −18.5% | −1.04 | Suppression of pathological fast oscillations |

| α Power (Left DLPFC) | Reduced | Increased | +19.7% | +0.81 | Restoration of cortical idling rhythms |

| θ/α Ratio (Left DLPFC) | High | Lowered | −15.5% | −1.63 | Improved excitation–inhibition balance |

| δ Power (Frontal) | Excessive | Reduced | −17–24% | >−1.4 | Resolution of slow-wave excess |

| θ Power (Frontal) | Excessive | Reduced | −25–30% | >−1.4 | Reduction of pathological low-frequency activity |

| Domain | Finding | Value/Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events | None reported | 0% |

| Common minor events | Transient headache (n = 2); mild fatigue during/after session | 3.6% (headache); <2% (fatigue) |

| Treatment discontinuations | None attributable to adverse effects | 0% |

| Session adherence | Median sessions completed | 39 of 40 (98%) |

| Caregiver acceptability | Mean satisfaction rating (5-point Likert scale, n = 46 respondents) | 4.5/5 |

| Caregiver feedback | Most frequent themes: improved sleep, calmer affect, better attention | Qualitative summary |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aydin, A.; Yildirim, A.; Duman, E.D. QEEG-Guided rTMS in Pediatric ASD with Contextual Evidence on Home-Based tDCS: Within-Cohort Reanalysis and Narrative Contextualization. Children 2025, 12, 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111453

Aydin A, Yildirim A, Duman ED. QEEG-Guided rTMS in Pediatric ASD with Contextual Evidence on Home-Based tDCS: Within-Cohort Reanalysis and Narrative Contextualization. Children. 2025; 12(11):1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111453

Chicago/Turabian StyleAydin, Alptekin, Ali Yildirim, and Ece Damla Duman. 2025. "QEEG-Guided rTMS in Pediatric ASD with Contextual Evidence on Home-Based tDCS: Within-Cohort Reanalysis and Narrative Contextualization" Children 12, no. 11: 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111453

APA StyleAydin, A., Yildirim, A., & Duman, E. D. (2025). QEEG-Guided rTMS in Pediatric ASD with Contextual Evidence on Home-Based tDCS: Within-Cohort Reanalysis and Narrative Contextualization. Children, 12(11), 1453. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111453