Longitudinal Association of Maternity Care Practices with Exclusive Breastfeeding in U.S. Hospitals, 2018–2022

Highlights

- •

- Certain maternity care practices and policies can support families to breastfeed.

- •

- Across the United States, hospitals that improved and sustained maternity care practices were more likely to have higher in-hospital exclusive breastfeeding rates.

- •

- Improving and sustaining maternity care practices and policies supportive of breastfeeding might increase in-hospital exclusive breastfeeding over time.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| EBF | Exclusive breastfeeding |

| mPINC | Maternity Practices in Infant Nutrition and Care |

Appendix A

| Outcome | Mediator | Exposure | Unstandardized Estimate (95% CI) b | Standardized Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

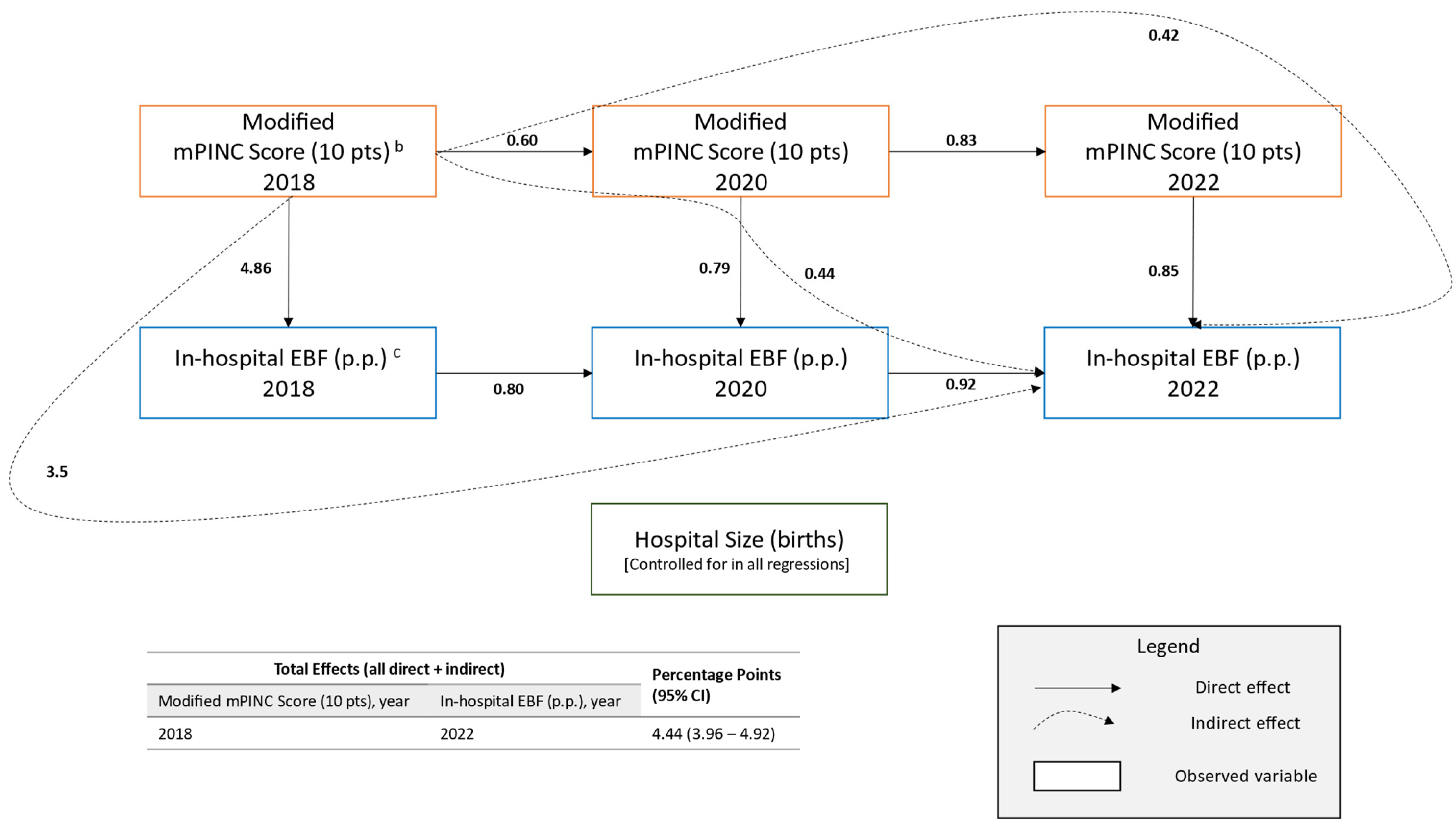

| Direct Effects | ||||

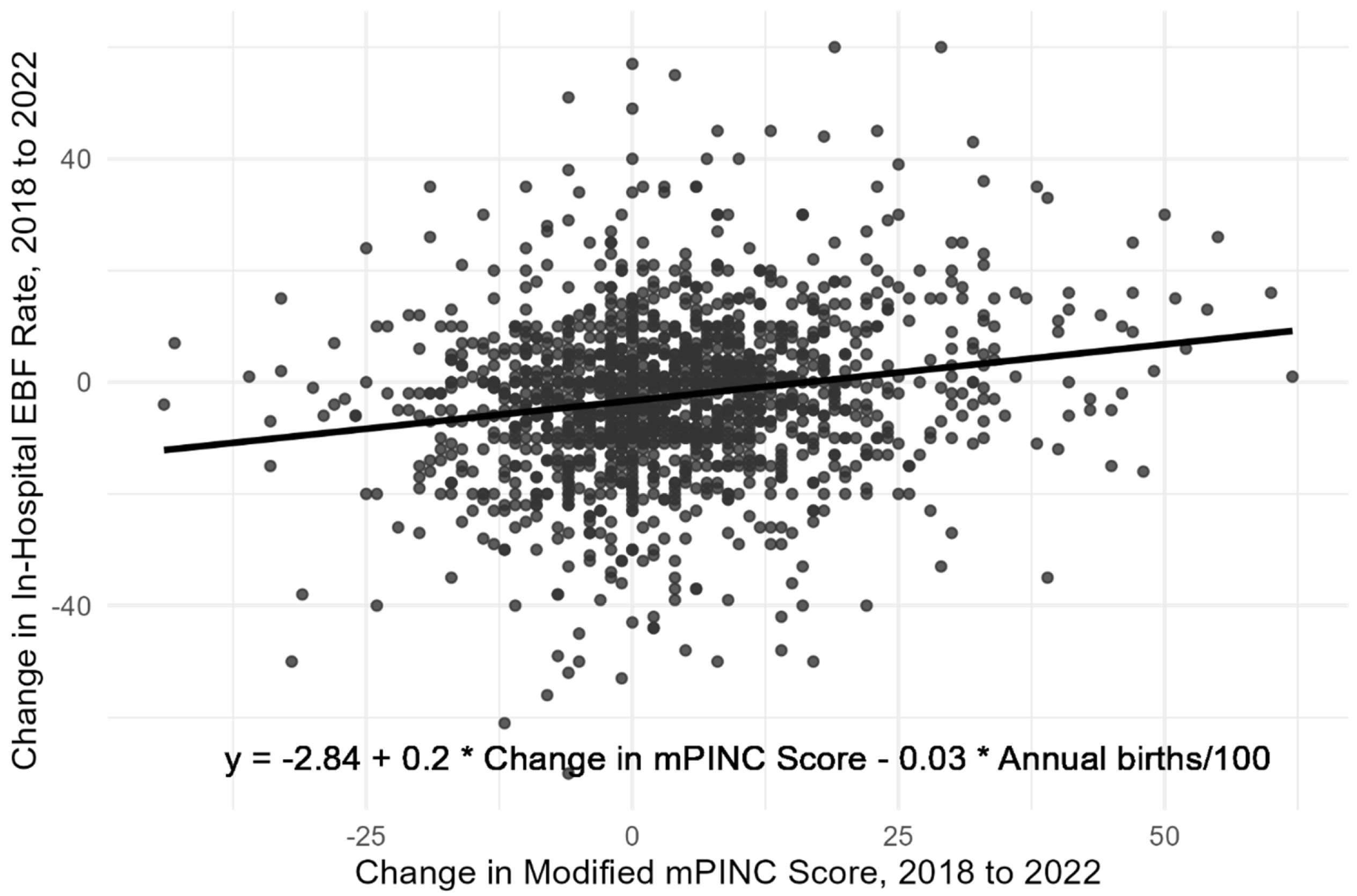

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) c | - | 2022 mPINC score (10 pts) d | 0.85 (0.40–1.30) | 0.06 (0.03–0.08) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.03 (−0.07–0.01) | −0.02 (−0.05–0.01) | |

| - | 2020 EBF rate (p.p.) | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) | |

| 2020 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2020 mPINC score (10 pts) | 0.79 (0.39–1.19) | 0.06 (0.03–0.08) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.07 (−0.11–−0.03) | −0.05 (−0.08–−0.02) | |

| - | 2018 EBF rate (p.p.) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83) | 0.80 (0.78–0.82) | |

| 2018 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 4.86 (4.30–5.41) | 0.38 (0.34–0.42) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.24 (−0.30–−0.18) | −0.17 (−0.21–−0.13) | |

| 2022 mPINC score (pts) | - | 2020 mPINC score (10 pts) | 0.83 (0.77–0.88) | 0.89 (0.84–0.93) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | 0.00 (0.00–0.01) | 0.02 (−0.02–0.06) | |

| 2020 mPINC score (pts) | - | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 0.60 (0.57–0.63) | 0.66 (0.64–0.69) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | 0.01 (0.00–0.01) | 0.08 (0.04–0.11) | |

| Indirect Effects | ||||

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2020 and 2022 mPINC score | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 0.42 (0.20–0.65) | 0.03 (0.01–0.05) |

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2018 and 2020 EBF rate | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 3.58 (3.14–4.01) | 0.27 (0.24–0.30) |

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2022 mPINC score and 2020 EBF rate | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 0.44 (0.21–0.66) | 0.03 (0.02–0.05) |

| Total Effects | ||||

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2018 mPINC score (10 pts) | 4.44 (3.96–4.92) | 0.34 (0.30–0.37) |

| Dependent Variable | Mediator | Independent Variable | Standardized to Latent Variables Estimate (95% CI) b | Standardized Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Factor Loadings c | ||||

| Immediate skin-to-skin contact (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | Maternity care practices (SD) | 0.24 (0.22–0.26) | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) |

| Transition to rooming-in (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | 0.09 (0.07–0.10) | 0.25 (0.22–0.29) | |

| Monitoring following birth (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | 0.09 (0.08–0.11) | 0.20 (0.17–0.24) | |

| Rooming-in (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | 0.14 (0.13–0.16) | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) | |

| Mother-infant separation (mother’s room for all vs. less) | - | 0.23 (0.21–0.25) | 0.53 (0.49–0.56) | |

| Rooming-in safety (protocol vs. no protocol) | - | 0.13 (0.11–0.14) | 0.28 (0.24–0.31) | |

| Glucose monitoring (no vs. yes) | - | 0.03 (0.02–0.05) | 0.12 (0.08–0.16) | |

| Formula counseling for breastfeeding mothers (almost always vs. less often) | - | 0.25 (0.23–0.27) | 0.51 (0.48–0.55) | |

| Feeding cues & pacifiers (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | 0.20 (0.18–0.21) | 0.45 (0.41–0.48) | |

| Identify/solve breastfeeding problems (≥80% vs. <80%) | - | 0.23 (0.21–0.24) | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) | |

| Nurse skill competency (6 skills vs. fewer) | - | 0.28 (0.26–0.30) | 0.58 (0.55–0.61) | |

| Nurse competency assessment (every 2 years vs. less often) | - | 0.21 (0.19–0.23) | 0.43 (0.40–0.47) | |

| Documentation of exclusive breastfeeding (yes vs. no) | - | 0.07 (0.06–0.08) | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | |

| Acquisition of infant formula (pays vs. free) | - | 0.31 (0.29–0.33) | 0.64 (0.61–0.67) | |

| Written policies (yes vs. no) | - | 0.31 (0.29–0.33) | 0.67 (0.64–0.70) | |

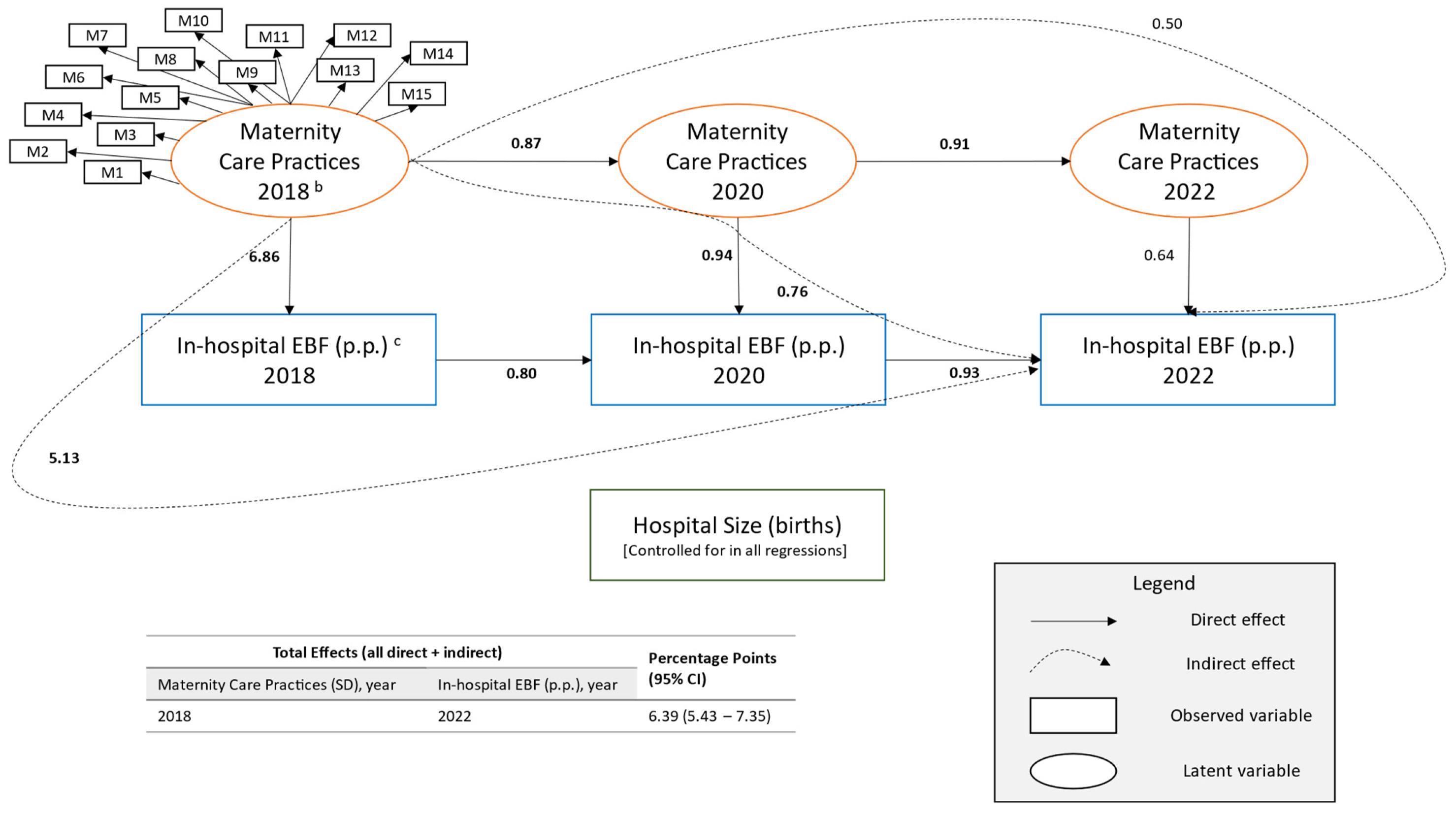

| Direct Effects | ||||

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) d | - | 2022 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.64 (−0.09–1.36) | 0.03 (0.00–0.06) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.02 (−0.06–0.02) | −0.01 (−0.04–0.02) | |

| - | 2020 EBF rate (p.p.) | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | |

| 2020 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2020 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.94 (0.28–1.60) | 0.04 (0.01–0.08) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.06 (−0.10–−0.02) | −0.05 (−0.07–−0.02) | |

| - | 2018 EBF rate (p.p.) | 0.80 (0.78–0.83) | 0.80 (0.78–0.82) | |

| 2018 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 6.86 (5.84–7.88) | 0.33 (0.28–0.37) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | −0.21 (−0.27–−0.15) | −0.15 (−0.19–−0.11) | |

| 2022 maternity care practices (pts) | - | 2020 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.02 (−0.02–0.06) | |

| 2020 maternity care practices (pts) | - | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.87 (0.84–0.89) | 0.87 (0.84–0.89) |

| - | Hospital size (100 births) | 0.01 (0.00–0.01) | 0.08 (0.04–0.11) | |

| Indirect Effects | ||||

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2020 and 2022 maternity care practices | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.50 (−0.07–1.08) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) |

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2018 and 2020 EBF rate | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 5.13 (4.33–5.92) | 0.24 (0.21–0.27) |

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | 2020 maternity care practices and 2020 EBF rate | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 0.76 (0.22–1.29) | 0.04 (0.01–0.06) |

| Total Effects | ||||

| 2022 EBF rate (p.p.) | - | 2018 maternity care practices (SD) | 6.39 (5.43–7.35) | 0.30 (0.26–0.34) |

References

- Chowdhury, R.; Sinha, B.; Sankar, M.J.; Taneja, S.; Bhandari, N.; Rollins, N.; Bahl, R.; Martines, J. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoody, E.E.; Spahn, J.M.; Casavale, K.O. The Pregnancy and Birth to 24 Months Project: A series of systematic reviews on diet and health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109 (Suppl. S7), 685S–697S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, S.; Chung, M.; Raman, G.; Chew, P.; Magula, N.; DeVine, D.; Trikalinos, T.; Lau, J. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. Full Rep. 2007, 153, 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Feltner, C.; Weber, R.P.; Stuebe, A.; Grodensky, C.A.; Orr, C.; Viswanathan, M. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. In Breastfeeding Programs and Policies, Breastfeeding Uptake, and Maternal Health Outcomes in Developed Countries; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NIS-Child Breastfeeding Rates. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/survey/results.html (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Meek, J.Y.; Noble, L. Technical Report: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Breastfeeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_2 (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Gavine, A.; Shinwell, S.C.; Buchanan, P.; Farre, A.; Wade, A.; Lynn, F.; Marshall, J.; Cumming, S.E.; Dare, S.; McFadden, A. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, CD001141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, E.C.; Osterman, M.J.; Valenzuela, C.P. Changes in Home Births by Race and Hispanic Origin and State of Residence of Mother:United States, 2019–2020 and 2020–2021. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; The United Nations Children’s Fund. Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services: Implementing the revised Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative 2018; World Health Organization, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bookhart, L.H.; Anstey, E.H.; Kramer, M.R.; Perrine, C.G.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Young, M.F. A dose–response relationship found between the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding indicators and in-hospital exclusive breastfeeding in US hospitals. Birth 2023, 50, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Martinez, J.L.; Segura-Pérez, S. Impact of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, J.A.; Keuler, N.S.; Olson, B.H. The effect of maternity practices on exclusive breastfeeding rates in U.S. hospitals. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahin, S.A.; McGurk, M.; Hansen-Smith, H.; West, M.; Li, R.; Melcher, C.L. Key Program Findings and Insights From the Baby-Friendly Hawaii Project. J. Hum. Lact. 2017, 33, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merewood, A.; Burnham, L.; Berger, J.; Gambari, A.; Safon, C.; Beliveau, P.; Logan-Hurt, T.; Nickel, N. Assessing the impact of a statewide effort to improve breastfeeding rates: A RE-AIM evaluation of CHAMPS in Mississippi. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.M.; Grossniklaus, D.A.; Galuska, D.A.; Perrine, C.G. The mPINC survey: Impacting US maternity care practices. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Supporting Evidence: Maternity Care Practices. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/mpinc/supporting-evidence.html (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scoring: Maternity Care Practices. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/mpinc/scoring.html (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. In Methodology in the Social Sciences, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 12–534. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, C.M.; Beauregard, J.L.; Nelson, J.M.; Perrine, C.G. Association of Maternity Care Practices and Policies with In-Hospital Exclusive Breastfeeding in the United States. Breastfeed. Med. 2019, 14, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whalen, B.L.; Kelly, J.; Holmes, A.V. The New Hampshire Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding Collaborative: A Statewide QI Initiative. Hosp. Pediatr. 2015, 5, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. mPINC 2024 National Results Report. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/mpinc/national-report.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

| Measure | Explanation | Survey Item(s) | Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain: Immediate Postpartum Care | Mean of 4 measures b | ||

| Immediate skin-to-skin contact | After vaginal delivery, percent of newborns who remain in uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact with their mothers immediately after birth if breastfeeding, until the first breastfeeding is completed, or if not breastfeeding, for at least 1 h. | C1_a1 C1_a2 | 100 = Most 70 = Many 30 = Some 0 = Few Items scored then averaged. |

| After Cesarean delivery, percent of newborns who remain in uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact with their mothers as soon as the mother is responsive and alert if breastfeeding, until the first breastfeeding is completed, or if not breastfeeding, for at least 1 h. | C2_a1 C2_a2 | 100 = Most 70 = Many 30 = Some 0 = Few Items scored then averaged. | |

| Transition to rooming-in | Percent of vaginally delivered newborns separated from their mothers before starting rooming-in. | C3 | 100 = Few 70 = Some 30 = Many 0 = Most OR Not an Option |

| Monitoring following birth | Percent of newborns who receive continuous observed monitoring throughout the first 2 h immediately following birth. | C5 | 100 = Most 70 = Many 30 = Some 0 = Few |

| Domain: Rooming-In | Mean of 3 measures | ||

| Rooming-in | Percent of newborns who stay in the room with their mothers for 24 h/day (not including separation for medical reasons). | C4_a1 | 100 = 80%+ 70 = 50–79% 30 = 20–49% 0 = <20% |

| Mother-infant separation | Indicates usual location of newborns during pediatric exams/rounds, hearing screening, pulse oximetry screening, routine labs/blood, draws/injections, and newborn bath. | C6_a1 C6_a2 C6_a4 C6_a5 C6_a6 | 100 = in mother’s room for all 5 situations 70 = removed from mother’s room for 1–2 situations 30 = removed from mother’s room for 3–4 situations 0 = removed from mother’s room for all 5 situations |

| Rooming-in safety | Indicates whether the hospital has a protocol requiring frequent observations, by nurses, of high-risk mother-infant dyads to ensure safety of the infant while they are together. | C7 | 100 = Yes 0 = No |

| Domain: Feeding Practices, Education, and Support c | Mean of 4 measures | ||

| Glucose monitoring | Indicates whether the hospital performs routine blood glucose monitoring of full-term healthy newborns NOT at risk for hypoglycemia. | D5 | 100 = No 0 = Yes |

| Formula counseling for breastfeeding mothers | Frequency with which staff counsel breastfeeding mothers who request infant formula—about possible health consequences for their infant and the success of breastfeeding. | E3 | 100 = Almost always 70 = Often 30 = Sometimes 0 = Rarely |

| Feeding cues & pacifiers | Percent of breastfeeding mothers who are taught or shown how to recognize and respond to their newborn’s feeding cues, breastfeed as often and as long as their newborn wants, and understand the use and risks of artificial nipples and pacifiers. | E2_a1 E2_a5 E2_a7 | 100 = Most 70 = Many 30 = Some 0 = Few Items scored then averaged. |

| Identify/solve breastfeeding problems | Percent of breastfeeding mothers who are taught or shown how to position and latch their newborn for breastfeeding, assess effective breastfeeding by observing their newborn’s latch and the presence of audible swallowing, assess effective breastfeeding by observing their newborn’s elimination patterns, and hand express breast milk. | E2_a2 E2_a3 E2_a4 E2_a6 | 100 = Most 70 = Many 30 = Some 0 = Few Items scored then averaged. |

| Domain: Institutional Management | Mean of 5 measures | ||

| Nurse skill competency | Indicates which competency skills are required of nurses: - Placing and monitoring of the newborn skin-to-skin with the mother immediately following birth. - Assisting with effective newborn positioning and latch for breastfeeding. - Assessment of milk transfer during breastfeeding. - Assessment of maternal pain related to breastfeeding. - Teaching hand expression of breast milk. - Teaching safe formula preparation and feeding. | F4_a1 F4_a2 F4_a3 F4_a4 F4_a5 F4_a6 | 100 = 6 skills 80 = 5 skills 65 = 4 skills 50 = 3 skills 35 = 2 skills 20 = 1 skill 0 = 0 skills |

| Nurse competency assessment | Assesses whether formal assessment of clinical competency in breastfeeding support and lactation management is required of nurses. | F3 | 100 = Required at least every 2 years OR Less than every 2 years 0 = Not required |

| Documentation of exclusive breastfeeding | Indicated whether the hospital records/tracks exclusive breastfeeding throughout the entire hospitalization. | G1_a1 | 100 = Yes 0 = No |

| Acquisition of infant formula | Indicates how the hospital acquires infant formula. | G4_a1 | 100 = Pays fair market price 0 = Receives free OR Unknown/Unsure |

| Written policies | Indicates whether the hospital has a policy requiring the following: - Documentation of medical justification or informed consent for giving non-breast milk feedings to breastfed newborns. - Formal assessment of staff’s clinical competency in breastfeeding support. - Documentation of prenatal breastfeeding education. - Staff to teach mothers breastfeeding techniques AND staff to show mothers how to express milk. - Purchase of infant formula and related breast milk substitutes by the hospital at fair market value AND a policy prohibiting distribution of free infant formula, infant feeding products, and infant formula coupons. - Staff to provide mothers with resources for support after discharge. - Placement of all newborns skin-to-skin with their mother at birth or soon thereafter. - The option for mothers to room-in with their newborns. | G2_a1 G2_a2 G2_a4 G2_a5/G2_a6 G2_a8/G2_a12 G2_a9 G2_a7 G2_a11 | 100 = Yes 0 = No Final score is a mean of the 8 scores d |

| Modified mPINC Score | Mean of 4 domains | ||

| Characteristics at First Survey | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 2109 | 100 |

| Hospital Ownership Type | ||

| Government/Military | 119 | 5.6 |

| Non-profit, private | 1626 | 77.1 |

| For profit, private | 364 | 17.3 |

| Hospital Size (annual births) | ||

| <250 | 347 | 16.5 |

| 250–499 | 382 | 18.1 |

| 500–999 | 466 | 22.1 |

| 1000–1999 | 454 | 21.5 |

| 2000–4999 | 407 | 19.3 |

| ≥5000 | 53 | 2.5 |

| Highest Level of Neonatal Care | ||

| Level I: Well newborn nursery | 842 | 40.0 |

| Level II: Special care nursery | 645 | 30.7 |

| Level III: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | 525 | 25.0 |

| Level IV: Regional Neonatal Intensive Care Unit | 91 | 4.3 |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 195 | 9.3 |

| Western | 289 | 13.7 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 216 | 10.2 |

| Midwest | 492 | 23.3 |

| Southwest | 337 | 16.0 |

| Mountain Plains | 241 | 11.4 |

| Southeast | 339 | 16.1 |

| In-Hospital Exclusive Breastfeeding b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (n = 1811) | 2020 (n = 1949) | 2022 (n = 1822) | |||||

| Practices | Score | n | % (SD) | n | % (SD) | n | % (SD) |

| Overall (0–100) c | 100 | 129 | 62.0 (18.2) | 132 | 62.2 (20.0) | 138 | 61.7 (19.2) |

| 80–99 | 839 | 59.8 (18.8) | 1046 | 57.1 (19.1) | 1044 | 54.7 (19.8) | |

| 60–79 | 596 | 54.6 (20.6) | 598 | 52.5 (21.8) | 513 | 50.9 (21.3) | |

| <60 | 247 | 40.6 (20.5) | 173 | 41.9 (22.4) | 127 | 37.8 (22.3) | |

| Immediate Postpartum Care (0–100) d | 100 | 612 | 60.9 (18.7) | 719 | 60.2 (19.8) | 703 | 58.3 (19.9) |

| 80–99 | 432 | 59.8 (19.4) | 506 | 55.6 (19.5) | 499 | 52.9 (20.2) | |

| 60–79 | 490 | 53.2 (20.3) | 495 | 52.4 (20.0) | 409 | 50.5 (20.8) | |

| <60 | 276 | 41.8 (20.1) | 228 | 40.6 (21.7) | 211 | 40.2 (20.0) | |

| Rooming-In (0–100) e | 100 | 352 | 61.5 (17.8) | 494 | 60.0 (18.9) | 465 | 56.1 (19.4) |

| 80–99 | 377 | 58.3 (19.7) | 425 | 54.6 (19.5) | 371 | 53.6 (21.1) | |

| 60–79 | 495 | 56.4 (20.5) | 574 | 54.2 (21.6) | 558 | 52.9 (20.5) | |

| <60 | 584 | 49.8 (21.4) | 455 | 49.6 (21.8) | 427 | 49.1 (22.4) | |

| Feeding Practices, Education, and Support (0–100) f | 100 | 807 | 60.3 (19.4) | 900 | 59.8 (19.2) | 859 | 56.7 (20.3) |

| 80–99 | 640 | 55.2 (19.8) | 741 | 52.4 (20.3) | 668 | 51.4 (20.4) | |

| 60–79 | 285 | 47.8 (20.4) | 253 | 46.5 (22.0) | 255 | 47.0 (21.3) | |

| <60 | 79 | 39.5 (22.4) | 55 | 40.0 (24.7) | 40 | 37.5 (21.7) | |

| Institutional Management (0–100) g | 100 | 382 | 60.9 (17.9) | 426 | 58.1 (19.1) | 467 | 55.6 (19.3) |

| 80–99 | 293 | 57.5 (20.4) | 362 | 55.7 (20.1) | 378 | 55.2 (20.0) | |

| 60–79 | 550 | 53.8 (20.5) | 558 | 53.0 (20.2) | 593 | 51.1 (20.4) | |

| <60 | 586 | 52.9 (21.8) | 603 | 53.3 (22.7) | 384 | 50.5 (23.8) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gosdin, L.; Marks, K.J.; Addo, O.Y.; O’Connor, L.; Awan, S.; Grossniklaus, D.A.; Hamner, H.C. Longitudinal Association of Maternity Care Practices with Exclusive Breastfeeding in U.S. Hospitals, 2018–2022. Children 2025, 12, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111454

Gosdin L, Marks KJ, Addo OY, O’Connor L, Awan S, Grossniklaus DA, Hamner HC. Longitudinal Association of Maternity Care Practices with Exclusive Breastfeeding in U.S. Hospitals, 2018–2022. Children. 2025; 12(11):1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111454

Chicago/Turabian StyleGosdin, Lucas, Kristin J. Marks, O. Yaw Addo, Lauren O’Connor, Sofia Awan, Daurice A. Grossniklaus, and Heather C. Hamner. 2025. "Longitudinal Association of Maternity Care Practices with Exclusive Breastfeeding in U.S. Hospitals, 2018–2022" Children 12, no. 11: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111454

APA StyleGosdin, L., Marks, K. J., Addo, O. Y., O’Connor, L., Awan, S., Grossniklaus, D. A., & Hamner, H. C. (2025). Longitudinal Association of Maternity Care Practices with Exclusive Breastfeeding in U.S. Hospitals, 2018–2022. Children, 12(11), 1454. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111454