Redefining Neurodevelopmental Impairment: Perspectives of Very Preterm Birth Stakeholders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of the Clinical Scenarios

2.2. Survey Administration

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Population Characteristics

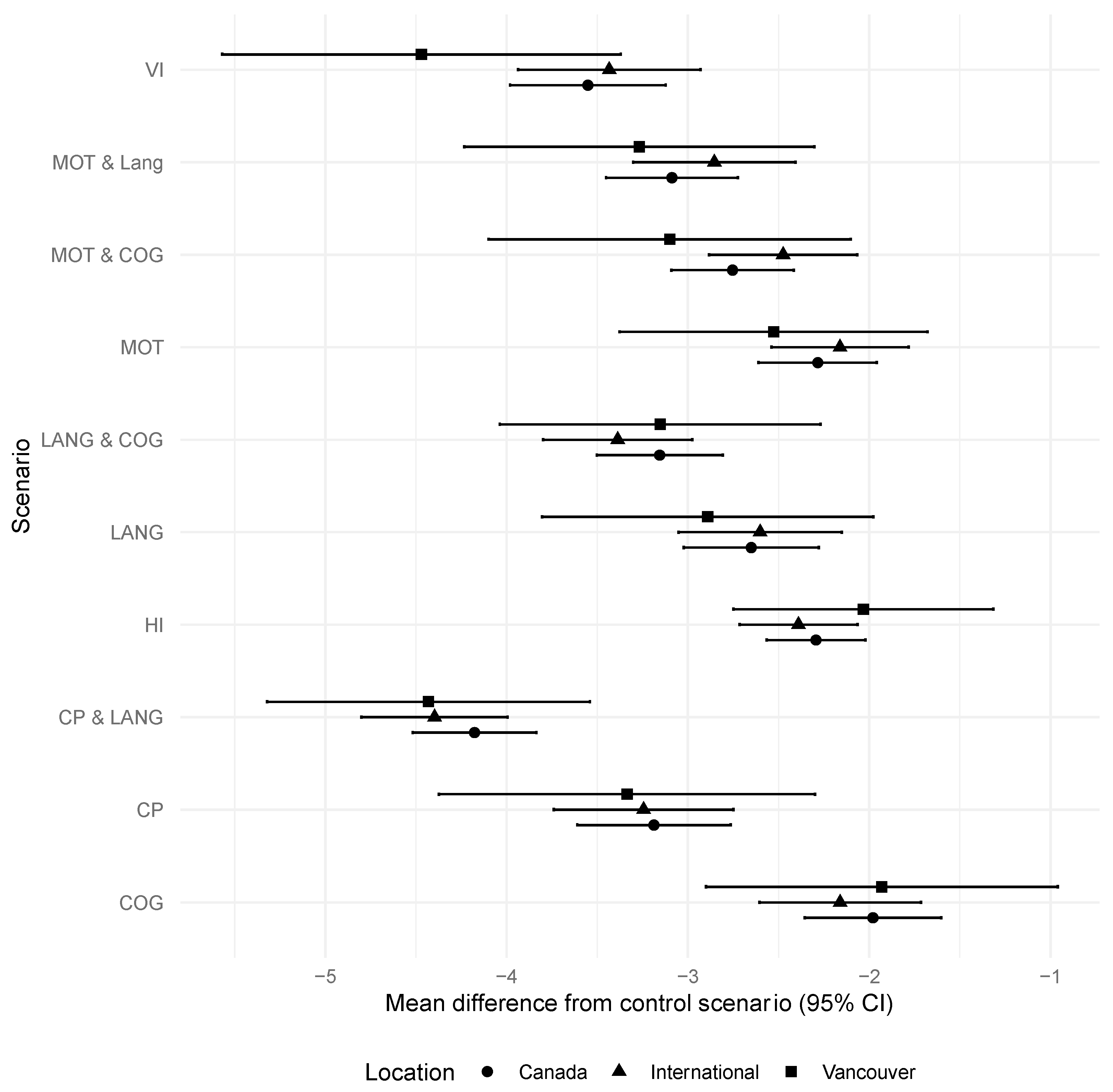

3.2. Severity Rating

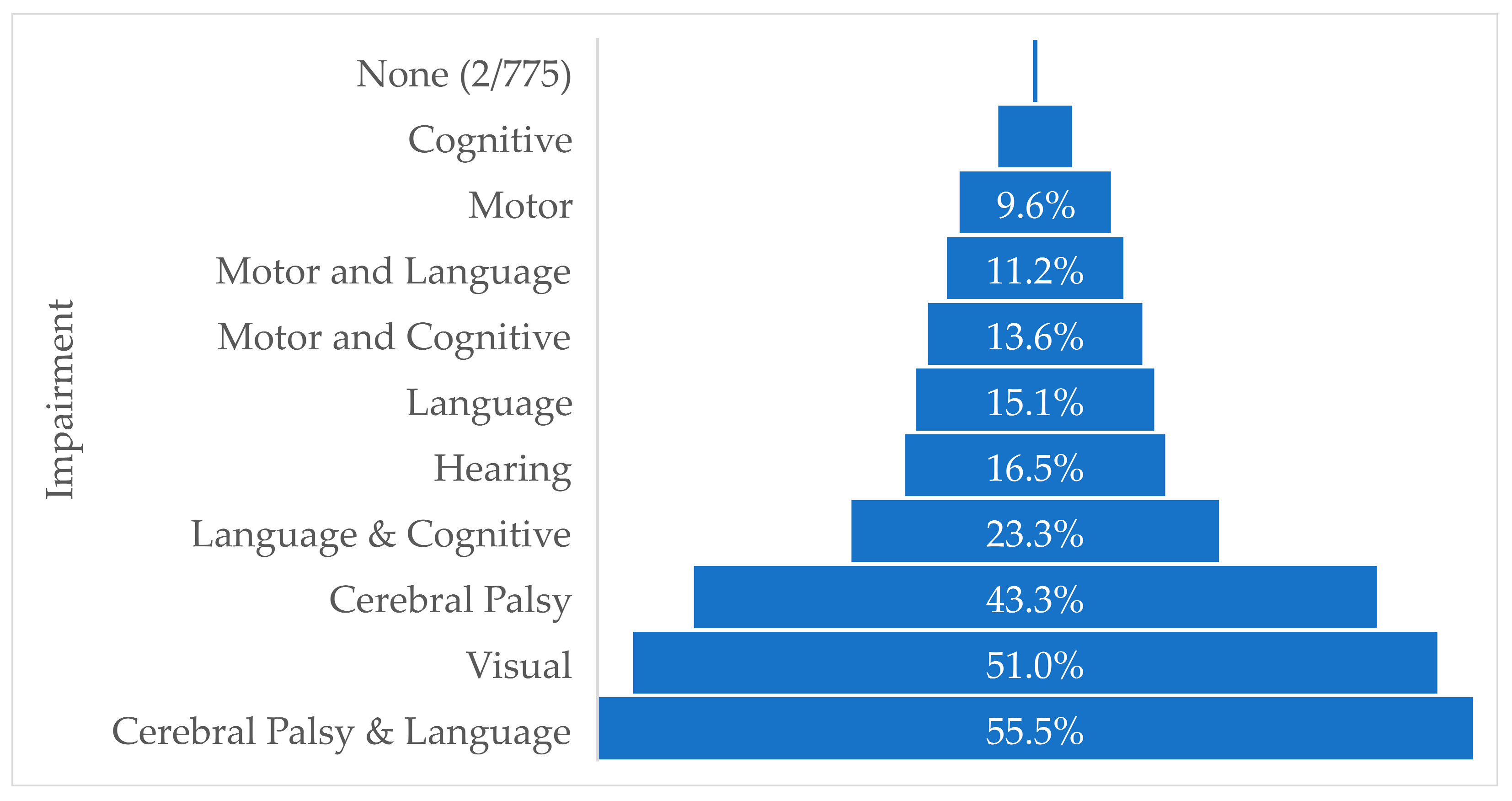

3.3. Classification of Scenario as a Severe Health Condition

3.4. Comparison of Respondent Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A. Clinical Scenarios

| SCENARIO 1 (Cerebral palsy) Jamie is an 18-month-old child. He can sit with support and roll and creep on his stomach. He has stiff legs and will very likely use a wheelchair for longer distances at school. He can see and hear normally. He learns like other children his age and likes to play with other children. He can follow simple directions and use words like other children his age. |

| SCENARIO 2 (Motor impairment) Riley is an 18-month-old child. She was slower at learning how to roll and sit. She now walks like an 11- to 12-month-old instead of an 18-month-old child. She will take three steps by herself but is unsteady and falls often. She can hold a crayon but is not able to scribble. She can see and hear normally. She is learning to play with toys like other children her age and likes to play with other children. She can follow simple directions and use words like other children her age. |

| SCENARIO 3 (Cognitive impairment) Max is an 18-month-old child. He likes to play with toys for younger children (10–12 months). He takes more time to learn new skills and needs more help doing so, compared to other children his age. He can see and hear normally. He walks, runs, and moves like other children his age. He can follow simple directions and use words like other children his age. |

| SCENARIO 4 (Language impairment) Lina is an 18-month-old child. She says ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ and one other word, which is less than expected for her age. She does not point to her ears and eyes when asked. She does not use words to make her wants known but cries or grabs you instead. She can see and hear normally. She walks, runs, and moves like other children her age. She learns, plays, and explores the environment like other children her age. |

| SCENARIO 5 (Visual impairment) Alex is an 18-month-old child. He is blind in both eyes but can see light and shadows with poor clarity. He can hear normally. He can walk at home but needs help to find his way and be safe outside, since he cannot see well. He is curious and plays and learns like other children his age except where good vision is needed. He can follow simple verbal directions and use words like other children his age. |

| SCENARIO 6 (Hearing impairment) Emilia is an 18-month-old child. With a hearing aid, she hears well but has difficulty in noisy environments. Without the hearing aid, she cannot understand regular speech. She can see normally. She learns, plays, and explores the environment like other children her age, but with the use of a hearing aid. With a hearing aid and regular speech therapy, she can follow simple directions and use words like other children her age. She walks, runs, and moves like other children her age. |

| SCENARIO 7 (Motor and language impairment) Ali is an 18-month-old child. He was slower at learning how to roll and sit. He now walks like an 11- to 12-month-old instead of an 18-month-old child. He will take three steps by himself but is unsteady and falls often. He can hold a crayon but is not able to scribble. He says ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ and one other word, which is less than expected for his age. He does not point to his ears and eyes when asked. He does not use words to make his wants known but cries or grabs you instead. He can see and hear normally. He is learning to play with toys like other children his age and likes to play with other children. |

| SCENARIO 8 (Cognitive and language impairment) Gracie is an 18-month-old child. She likes to play with toys for younger children (10–12 months). She takes more time to learn new skills and needs more help doing so, compared to other children her age. She says ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ and one other word, which is less than expected for her age. She does not point to her ears and eyes when asked. She does not use words to make her wants known but cries or grabs you instead. She can see and hear normally. She walks, runs, and moves like other children her age. |

| SCENARIO 9 (Motor and cognitive impairment) Lee is an 18-month-old child. He was slower at learning how to roll and sit. He now walks like an 11- to 12-month-old instead of an 18-month-old child. He will take three steps by himself but is unsteady and falls often. He can hold a crayon but is not able to scribble. He likes to play with toys for younger children (10–12 months). He takes more time to learn new skills and needs more help doing so, compared to other children his age. He can see and hear normally. He can follow simple directions and use words like other children his age. |

| SCENARIO 10 (Cerebral palsy and language impairment) Bailey is an 18-month-old child. She can sit with support and roll and creep on her stomach. She has stiff legs and will very likely use a wheelchair for longer distances at school. She says ‘mama’ and ‘dada’ and one other word, which is less than expected for her age. She does not point to her ears and eyes when asked. She does not use words to make her wants known but cries or grabs you instead. She can see and hear normally. She learns like other children her age and likes to play with other children. |

| SCENARIO 11 (Typically developing child) Tasha is an 18-month-old child. She can see and hear normally. She walks, runs, and moves like other children her age. She learns, plays, and explores the environment like other children her age. She can follow simple directions and use words like other children her age. |

| Questions: If 0 is the worst possible health and 10 is the best possible health, where do you think __ fits on the scale? _0 _1 _2 _3 _4 _5 _6 _7 _8 _9 _10 Does __’s case describe a severe health condition? _Y _N (repeat for all scenarios) |

References

- Walani, S.R. Global burden of preterm birth. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 150, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control. Preterm Birth. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pretermbirth.htm#print (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Shah, P.S.; Ye, X.Y.; Yang, J.; Campitelli, M.A. Preterm birth and stillbirth rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: A population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2021, 193, E1164–E1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, E.F.; Hintz, S.R.; Hansen, N.I.; Bann, C.M.; Wyckoff, M.H.; DeMauro, S.B.; Walsh, M.C.; Vohr, B.R.; Stoll, B.J.; Carlo, W.A.; et al. Mortality, In-Hospital Morbidity, Care Practices, and 2-Year Outcomes for Extremely Preterm Infants in the US, 2013–2018. JAMA 2022, 327, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, A.; Lain, S.; Roberts, C.; Bowen, J.R.; Nassar, N. Survival, Hospitalization, and Acute-Care Costs of Very and Moderate Preterm Infants in the First 6 Years of Life: A Population-Based Study. J. Pediatr. 2016, 169, 61–68.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrou, S.; Eddama, O.; Mangham, L. A structured review of the recent literature on the economic consequences of preterm birth. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010, 96, F225–F232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drillien, C.M. Growth and Development in a Group of Children of Very Low Birth Weight. Arch. Dis. Child. 1958, 33, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, B.; Anderson, P.J.; Doyle, L.W.; Dewey, D.; Grunau, R.E.; Asztalos, E.V.; Davis, P.G.; Tin, W.; Moddemann, D.; Solimano, A.; et al. Survival without disability to age 5 years after neonatal caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity. JAMA 2012, 307, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayley, N. Manual for the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd ed.; The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Albaghli, F.; Church, P.; Ballantyne, M.; Girardi, A.; Synnes, A. Neonatal follow-up programs in Canada: A national survey. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2021, 26, e46–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follow-up Care of High-Risk Infants. Pediatrics 2004, 114 (Suppl. S5), 1377–1397. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Foglia, E.E.; DeMauro, S.B.; Chawla, S.; Brion, L.P.; Wyckoff, M.H. Perinatal management: Lessons learned from the neonatal research network. Semin. Perinatol. 2022, 46, 151636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mactier, H.; Bates, S.E.; Johnston, T.; Lee-Davey, C.; Marlow, N.; Mulley, K.; Smith, L.K.; To, M.; Wilkinson, D. Perinatal management of extreme preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation: A framework for practice. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020, 105, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haward, M.F.; Payot, A.; Feudtner, C.; Janvier, A. Personalized communication with parents of children born at less than 25 weeks: Moving from doctor-driven to parent-personalized discussions. Semin. Perinatol. 2020, 46, 151551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Synnes, A.; Luu, T.M.; Moddemann, D.; Church, P.; Lee, D.; Vincer, M.; Ballantyne, M.; Majnemer, A.; Creighton, D.; Yang, J.; et al. Determinants of developmental outcomes in a very preterm Canadian cohort. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017, 102, F235–F234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, M.D.; Lisonkova, S.; Creighton, D.; Church, P.; Yang, J.; Shah, P.S.; Joseph, K.; Synnes, A.; Harrison, A.; Ting, J.; et al. Severe Neurodevelopmental Impairment in Neonates Born Preterm: Impact of Varying Definitions in a Canadian Cohort. J. Pediatr. 2018, 197, 75–81.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysavy, M.A.; Horbar, J.D.; Bell, E.F.; Li, L.; Greenberg, L.T.; Tyson, J.E.; Patel, R.M.; Carlo, W.A.; Younge, N.E.; Green, C.E.; et al. Assessment of the Neonatal Research Network Extremely Preterm Birth Outcome Model in the Vermont Oxford Network. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, e196294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montori, V.M.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Ferreira-González, I.; Busse, J.; Pacheco-Huergo, V.; Bryant, D.; Alonso, J.; A Akl, E.; Domingo-Salvany, A.; Mills, E.; et al. Validity of composite end points in clinical trials. BMJ 2005, 330, 594–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-González, I.; Permanyer-Miralda, G.; Busse, J.; Bryant, D.; Montori, V.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Walter, S.D.; Guyatt, G.H. Methodologic discussions for using and interpreting composite endpoints are limited, but still identify major concerns. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2007, 60, 651–657, discussion 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordoba, G.; Schwartz, L.; Woloshin, S.; Bae, H.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Definition, reporting, and interpretation of composite outcomes in clinical trials: Systematic review. BMJ 2010, 341, c3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHILD-BRIGHT Network. What Is CHILD-BRIGHT. Available online: https://www.child-bright.ca (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network. Outcomes Definitions in Canadian Neonatal Follow-Up Network Annual Report 2021. 17. Available online: https://canadianneonatalfollowup.ca/annual-report/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Palisano, R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glen, S. Snowball Sampling: Definition, Advantages and Disadvantages. Available online: https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/statistics-definitions/snowball-sampling/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Werner, S.; Shulman, C. Subjective well-being among family caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities: The role of affiliate stigma and psychosocial moderating variables. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 4103–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saigal, S. Quality of life of former premature infants during adolescence and beyond. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webbe, J.W.H.; Duffy, J.M.N.; Afonso, E.; Al-Muzaffar, I.; Brunton, G.; Greenough, A.; Hall, N.J.; Knight, M.; Latour, J.M.; Lee-Davey, C.; et al. Core outcomes in neonatology: Development of a core outcome set for neonatal research. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020, 105, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janvier, A.; Lantos, J.; Deschênes, M.; Couture, E.; Nadeau, S.; Barrington, K.J. Caregivers attitudes for very premature infants: What if they knew? Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.J.; Burnett, A. Assessing developmental delay in early childhood — Concerns with the Bayley-III scales. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2017, 31, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, M.; Janvier, A.; Lefebvre, F.; Luu, T.M. Parental Perspectives Regarding Outcomes of Very Preterm Infants: Toward a Balanced Approach. J. Pediatr. 2018, 200, 58–63.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, M.; Janvier, A.; Bourque, C.J.; Mai-Vo, T.-A.; Pearce, R.; Synnes, A.R.; Luu, T.M. Parental perspective on important health outcomes of extremely preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 2021, 107, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milette, A.A.; Richter, L.L.; Bourque, C.J.; Janvier, A.; Pearce, R.; Church, P.T.; Synnes, A.; Luu, T.M. Parental perspectives of outcomes following very preterm birth: Seeing the good, not just the bad. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, L.L.; Luu, T.M.; Janvier, A.; Pearce, R.; Bourque, C.J.; Church, P.; Synnes, A. Investigating the agreement between parents’ classification of their very preterm child’s neurodevelopmental impairment status and the Canadian Neonatal Follow up Network classification. In Proceedings of the Canadian National Perinatal Research Meeting, Montebello, CA, Canada, 11 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.C. Preterm outcomes research: A critical component of neonatal intensive care. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2002, 8, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N (%) (N = 827) | |

|---|---|---|

| Language of Questionnaire | English | 354 (43%) |

| French | 473 (57%) | |

| Personal or Professional Description | Parent/caregiver or family of a child born preterm | 471 (57%) |

| Person born preterm | 21 (3%) | |

| Healthcare professional | 228 (28%) | |

| Teacher/educator | 14 (2%) | |

| Student/trainee | 5 (1%) | |

| Researcher | 14 (2%) | |

| Other | 9 (1%) | |

| Country of Residence (international survey only) | United States | 54 (6.5%) |

| United Kingdom | 26 (3.1%) | |

| France | 181 (21.9%) | |

| Other | 62 (7.5%) |

| Scenario | Mean Differences (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| No impairment | −0.06 (−0.3, 0.17) | 0.60 |

| Cerebral palsy | −0.23 (−0.61, 0.16) | 0.25 |

| Motor | −0.04 (−0.32, 0.25) | 0.81 |

| Cognitive | 0.25 (−0.09, 0.59) | 0.16 |

| Language | 0.14 (−0.2, 0.48) | 0.41 |

| Visual impairment | 0.03 (−0.36, 0.41) | 0.89 |

| Hearing impairment | −0.22 (−0.46, 0.2) | 0.07 |

| Motor and language | 0 (−0.34, 0.33) | 0.99 |

| Language and cognitive | 0.24 (−0.08, 0.55) | 0.14 |

| Motor and cognitive | −0.03 (−0.34, 0.28) | 0.83 |

| Cerebral palsy and language | −0.36 (−0.66, −0.05) | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Synnes, A.; Chera, A.; Richter, L.L.; Bone, J.N.; Bourque, C.J.; Zhang-Jiang, S.; Pearce, R.; Janvier, A.; Luu, T.M. Redefining Neurodevelopmental Impairment: Perspectives of Very Preterm Birth Stakeholders. Children 2023, 10, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050880

Synnes A, Chera A, Richter LL, Bone JN, Bourque CJ, Zhang-Jiang S, Pearce R, Janvier A, Luu TM. Redefining Neurodevelopmental Impairment: Perspectives of Very Preterm Birth Stakeholders. Children. 2023; 10(5):880. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050880

Chicago/Turabian StyleSynnes, Anne, Amarpreet Chera, Lindsay L. Richter, Jeffrey N. Bone, Claude Julie Bourque, Sofia Zhang-Jiang, Rebecca Pearce, Annie Janvier, and Thuy Mai Luu. 2023. "Redefining Neurodevelopmental Impairment: Perspectives of Very Preterm Birth Stakeholders" Children 10, no. 5: 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050880

APA StyleSynnes, A., Chera, A., Richter, L. L., Bone, J. N., Bourque, C. J., Zhang-Jiang, S., Pearce, R., Janvier, A., & Luu, T. M. (2023). Redefining Neurodevelopmental Impairment: Perspectives of Very Preterm Birth Stakeholders. Children, 10(5), 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10050880