Intervention Programme Based on Self-Determination Theory to Promote Extracurricular Physical Activity through Physical Education in Primary School: A Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Activity and Self-Determination Theory

1.2. Previous Intervention Studies Based on SDT in the School Context

1.3. The Present Study

2. Methods

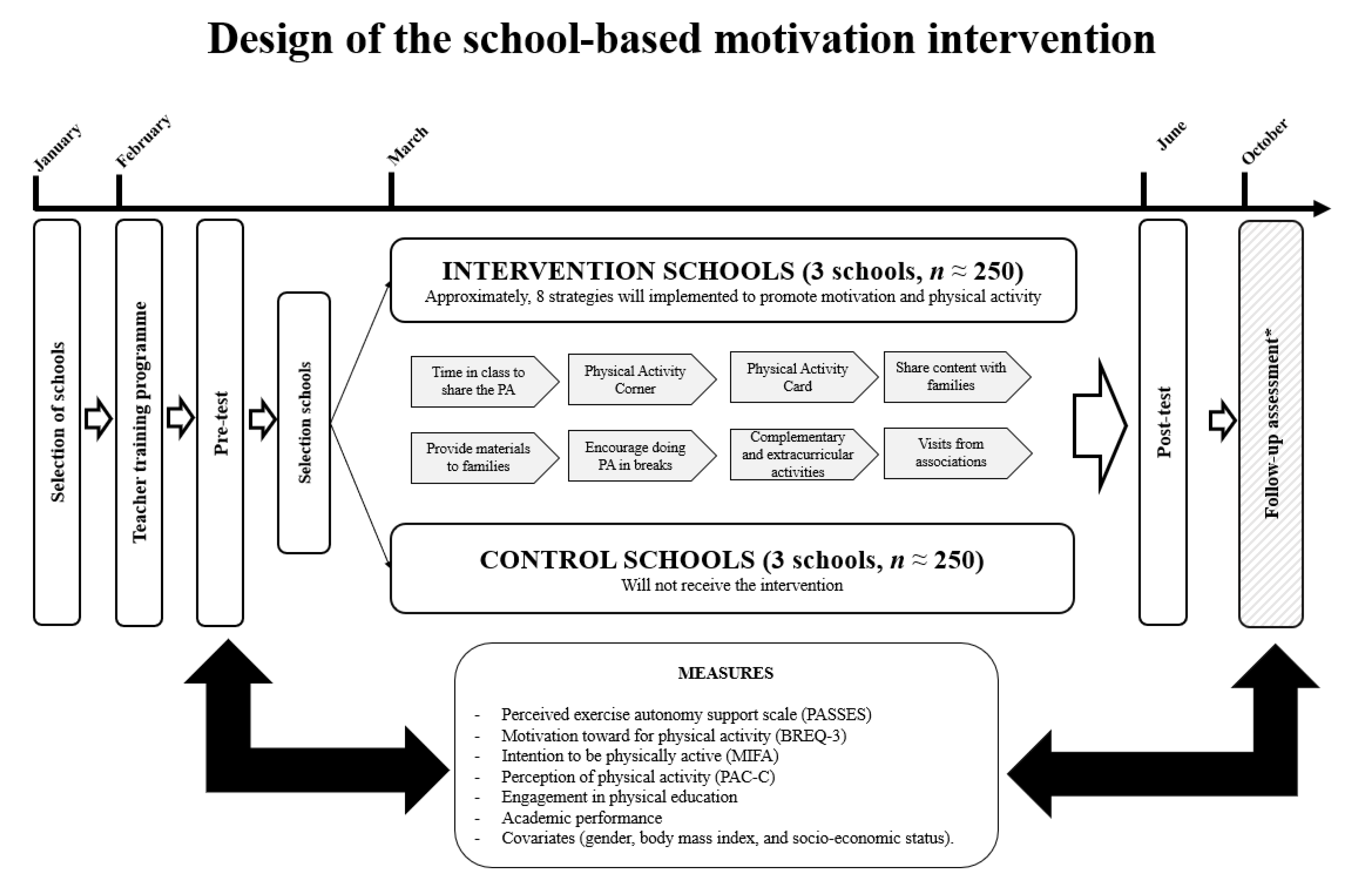

2.1. Design and Participants

2.1.1. Selection Process and School Characteristics

2.1.2. Teachers’ Training Program

2.1.3. Students’ Characteristics

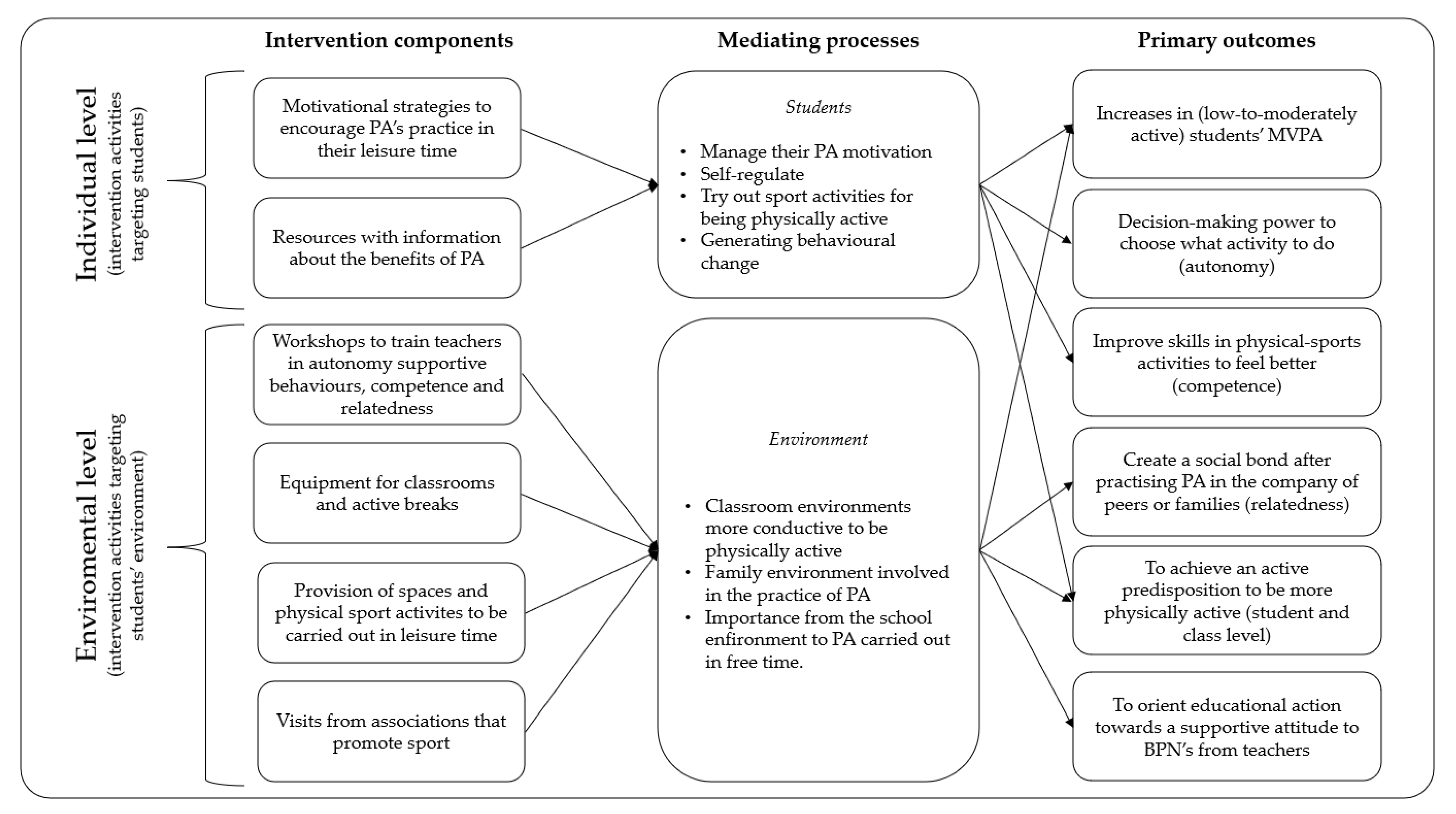

2.2. Intervention Based on SDT in Primary School

2.3. Measures

| Variable | Instrument |

|---|---|

| Socio-economic status | FAS Scale [46] |

| Height | Stadiometer |

| Weight | Weighing machine |

| Perceived Need Support in PA | PASSES [47] |

| Motivation toward physical activity | BREQ-3 [49] |

| Intention to be physically active | MIFA [51] |

| Perception of physical activity levels | PAQ-C [53] |

| Engagement in physical education | Physical Education Engagement Questionnaire [55] |

| Academic performance | Grades obtained in 1st and 2nd trimester |

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Cadenas-Sánchez, C.; Estévez-López, F.; Muñoz, N.E.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Molina-García, P.; Henriksson, H.; Mena-Molina, A.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 2019, 49, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.S.; Saliasi, E.; van den Berg, V.; Uijtdewilligen, L.; de Groot, R.H.M.; Jolles, J.; Andersen, L.B.; Bailey, R.; Chang, Y.-K.; Diamond, A.; et al. Effects of Physical Activity Interventions on Cognitive and Academic Performance in Children and Adolescents: A Novel Combination of a Systematic Review and Recommendations from an Expert Panel. Br. J. Sport. Med. 2019, 53, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1·6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Demchenko, I.; Hawthorne, M.; Abdeta, C.; Abi Nader, P.; Sala, J.C.A.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Aznar, S.; Bakalár, P.; et al. Global Matrix 4.0 Physical Activity Report Card Grades for Children and Adolescents: Results and Analysis from 57 Countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 700–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grao-Cruces, A.; Velásquez-Romero, M.J.; Rodriguez-Rodríguez, F. Levels of Physical Activity during School Hours in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelso, A.; Linder, S.; Reimers, A.K.; Klug, S.J.; Alesi, M.; Scifo, L.; Borrego, C.C.; Monteiro, D.; Demetriou, Y. Effects of School-Based Interventions on Motivation towards Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 51, 101770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical Explanations for Maintenance of Behaviour Change: A Systematic Review of Behaviour Theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazowski, R.A.; Hulleman, C.S. Motivation Interventions in Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 602–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaquero-Solís, M.; Gallego, D.I.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; Pulido, J.J.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A. School-Based Physical Activity Interventions in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: Definitions, Theory, Practices, and Future Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A Model of Contextual Motivation in Physical Education: Using Constructs from Self-Determination and Achievement Goal Theories to Predict Physical Activity Intentions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadnia, B.; Adachi, P.J.C.; Deci, E.L.; Mohammadzadeh, H. Associations between Students’ Perceptions of Physical Education Teachers’ Interpersonal Styles and Students’ Wellness, Knowledge, Performance, and Intentions to Persist at Physical Activity: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 39, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, F.M.; Mouratidis, A.; Pulido, J.J.; López-Gajardo, M.A.; Sánchez-Oliva, D. Perceived Teachers’ Behavior and Students’ Engagement in Physical Education: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs and Self-Determined Motivation. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2022, 27, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. The Perceived Autonomy Support Scale for Exercise Settings (PASSES): Development, Validity, and Cross-Cultural Invariance in Young People. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 632–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, C.K.J.; Baranowski, J. Perceived Autonomy Support in Physical Education and Leisure-Time Physical Activity: A Cross-Cultural Evaluation of the Trans-Contextual Model. J. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 97, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirakca, T.; Brusniak, W.; Tunc-Skarka, N.; Wolf, I.; Meier, S.; Matthäus, F.; Ende, G.; Schulze, T.G.; Diener, C. Does Body Shaping Influence Brain Shape? Habitual Physical Activity Is Linked to Brain Morphology Independent of Age. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 15, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.G.; Dennis, A.; Bandettini, P.A.; Johansen-Berg, H. The Effects of Aerobic Activity on Brain Structure. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Review of Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.A.; Hillman, C.H. The Relation of Childhood Physical Activity and Aerobic Fitness to Brain Function and Cognition: A Review. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2014, 26, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Koka, A.; Hein, V.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L. Motivational Processes in Physical Education and Objectively Measured Physical Activity among Adolescents. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalajas-Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Tilga, H.; Raudsepp, L.; Hagger, M.S. Application of the Trans-Contextual Model to Predict Change in Leisure Time Physical Activity. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 62–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, J.; Hagger, M.S.; Haukkala, A.; Araújo-Soares, V.; Hankonen, N. Relations Between Autonomous Motivation and Leisure-Time Physical Activity Participation: The Mediating Role of Self-Regulation Techniques. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevil-Serrano, J.; García-González, L.; Abós, Á.; Aibar Solana, A.; Simón-Montañés, L. Orientaciones Para La Comunidad Científica Sobre El Diseño, Implementación y Evaluación de Intervenciones Escolares Sobre Promoción de Comportamientos Saludables (Guidelines for the Scientific Community on the Design, Implementation, and Evaluation of Sch). Cult. Cienc. Y Deporte 2020, 15, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D.; Parker, P.D.; Hilland, T.; Cinelli, R.; Owen, K.B.; Kapsal, N.; Lee, J.; Antczak, D.; Ntoumanis, N.; Ryan, R.M.; et al. Self-Determination Theory Applied to Physical Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillison, F.B.; Rouse, P.; Standage, M.; Sebire, S.J.; Ryan, R.M. A Meta-Analysis of Techniques to Promote Motivation for Health Behaviour Change from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 13, 110–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; García-López, L.M.; Serra-Olivares, J. Sport Education Model and Self-Determination Theory. Kinesiology 2016, 48, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkonen, J.; Yli-Piipari, S.; Kokkonen, M.; Quay, J. Effectiveness of a Creative Physical Education Intervention on Elementary School Students’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity Motivation and Overall Physical Activity in Finland. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 796–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Piipari, S.; Layne, T.; Hinson, J.; Irwin, C. Motivational Pathways to Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Urban Physical Education: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2018, 37, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, Y.; Höner, O. Physical Activity Interventions in the School Setting: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, R.; Spray, C.M.; Warburton, V.E. Motivational Climate Interventions in Physical Education: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Sánchez-Latorre, F. The Effects of Autonomy Support in Physical Education Classes [Efectos Del Soporte de Autonomía En Clases de Educación Física]. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2016, 12, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute, E.S. Junta de Extremadura. Available online: https://ciudadano.gobex.es/web/ieex (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Beauchamp, M.R.; Puterman, E.; Lubans, D.R. Physical Inactivity and Mental Health in Late Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceschini, F.L.; Andrade, D.R.; Oliveira, L.C.; Araújo Júnior, J.F.; Matsudo, V.K.R. Prevalência de Inatividade Física e Fatores Associados Em Estudantes Do Ensino Médio de Escolas Públicas Estaduais. J. Pediatr. 2009, 85, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Harvey, S.; Savory, L.; Fairclough, S.; Kozub, S.; Kerr, C. Physical Activity Levels and Motivational Responses of Boys and Girls. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2015, 21, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Baranowski, T.; Lau, P.W.C.; Buday, R.; Gao, Y. Story Immersion May Be Effective in Promoting Diet and Physical Activity in Chinese Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 321–329.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, S.; Brennan, D.; Hanna, D.; Younger, Z.; Hassan, J.; Breslin, G. The Effect of a School-Based Intervention on Physical Activity and Well-Being: A Non-Randomised Controlled Trial with Children of Low Socio-Economic Status. Sport. Med.-Open 2018, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odle-Dusseau, H.N.; Hammer, L.B.; Crain, T.L.; Bodner, T.E. The Influence of Family-Supportive Supervisor Training on Employee Job Performance and Attitudes: An Organizational Work–Family Intervention. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, S.; Tavafian, S.; Hiller, C.E.; Hidarnia, A.; Montazeri, A. The Effectiveness of Social Media and In-person Interventions for Low Back Pain Conditions in Nursing Personnel (SMILE). Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.E.; Bierman, K.L.; Crowley, D.M.; Welsh, J.A.; Gest, J. Important Issues in Estimating Costs of Early Childhood Educational Interventions: An Example from the REDI Program. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Thrasher, J.; Monzón, J.C.; Arillo-Santillán, E.; Barnoya, J.; Mejía, R. La Escala de Afluencia Familiar En La Investigación Sobre Inequidades Sociales En Salud En Adolescentes Latinoamericanos. Salud Publica Mex. 2021, 63, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Parra-Rojas, N.; González-Cutre, D. Influencia Del Apoyo a La Autonomía, Las Metas Sociales y La Relación Con Los Demás Sobre La Desmotivación En Educación Física. Psicothema 2008, 20, 636–641. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rodgers, W.M.; Loitz, C.C.; Scime, G. It’s Who I Am… Really! The Importance of Integrated Regulation in Exercise Contexts. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2006, 11, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, Á.; Fernández, A. Hacia Una Mayor Comprensión de La Motivación En El Ejercicio Física: Medición de La Regulación Integrada En El Contexto Español. Psicothema 2010, 22, 841–847. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, V.; Müür, M.; Koka, A. Intention to Be Physically Active after School Graduation and Its Relationship to Three Types of Intrinsic Motivation. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2004, 10, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; Moreno, R.; Cervelló, E. El Autoconcepto Físico Como Predictor de La Intención de Ser Físicamente Activo. Psicol. Y Salud 2007, 17, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, J.L.; Castejón, F.J.; Yuste, J.L. Propiedades Psicométricas de La Escala de Intencionalidad de Ser Físicamente Activo En Educación Primaria. Rev. Educ. 2013, 362, 485–505. [Google Scholar]

- Benítez-Porres, J.; López-Fernández, I.; Raya, J.F.; Álvarez Carnero, S.; Alvero-Cruz, J.R.; Álvarez Carnero, E. Reliability and Validity of the PAQ-C Questionnaire to Assess Physical Activity in Children. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J.J.; Fahlman, M.; Garn, A.C. Urban High-School Girls’ Sense of Relatedness and Their Engagement in Physical Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2012, 31, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado-Renau, M.; Beltran-Valls, M.R.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Santaliestra-Pasías, A.M.; Moliner-Urdiales, D. The Influence of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet on Academic Performance Is Mediated by Sleep Quality in Adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Izquierdo-Gomez, R.; Gómez-Martínez, S.; Padilla-Moledo, C.; Castro-Piñero, J.; Marcos, A.; Veiga, O.L. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Academic Performance in Youth: The UP&DOWN Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016, 55, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polet, J.; Hassandra, M.; Lintunen, T.; Laukkanen, A.; Hankonen, N.; Hirvensalo, M.; Tammelin, T.; Hagger, M.S. Using Physical Education to Promote Out-of School Physical Activity in Lower Secondary School Students—A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilga, H.; Hein, V.; Koka, A.; Hamilton, K.; Hagger, M.S. The Role of Teachers’ Controlling Behaviour in Physical Education on Adolescents’ Health-Related Quality of Life: Test of a Conditional Process Model*. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 39, 862–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llanos-Muñoz, R.; Vaquero-Solís, M.; López-Gajardo, M.Á.; Sánchez-Miguel, P.A.; Tapia-Serrano, M.Á.; Leo, F.M. Intervention Programme Based on Self-Determination Theory to Promote Extracurricular Physical Activity through Physical Education in Primary School: A Study Protocol. Children 2023, 10, 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030504

Llanos-Muñoz R, Vaquero-Solís M, López-Gajardo MÁ, Sánchez-Miguel PA, Tapia-Serrano MÁ, Leo FM. Intervention Programme Based on Self-Determination Theory to Promote Extracurricular Physical Activity through Physical Education in Primary School: A Study Protocol. Children. 2023; 10(3):504. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030504

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlanos-Muñoz, Rubén, Mikel Vaquero-Solís, Miguel Ángel López-Gajardo, Pedro Antonio Sánchez-Miguel, Miguel Ángel Tapia-Serrano, and Francisco Miguel Leo. 2023. "Intervention Programme Based on Self-Determination Theory to Promote Extracurricular Physical Activity through Physical Education in Primary School: A Study Protocol" Children 10, no. 3: 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030504

APA StyleLlanos-Muñoz, R., Vaquero-Solís, M., López-Gajardo, M. Á., Sánchez-Miguel, P. A., Tapia-Serrano, M. Á., & Leo, F. M. (2023). Intervention Programme Based on Self-Determination Theory to Promote Extracurricular Physical Activity through Physical Education in Primary School: A Study Protocol. Children, 10(3), 504. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030504