Choledochal Cyst Excision in Infants—A Retrospective Study

Abstract

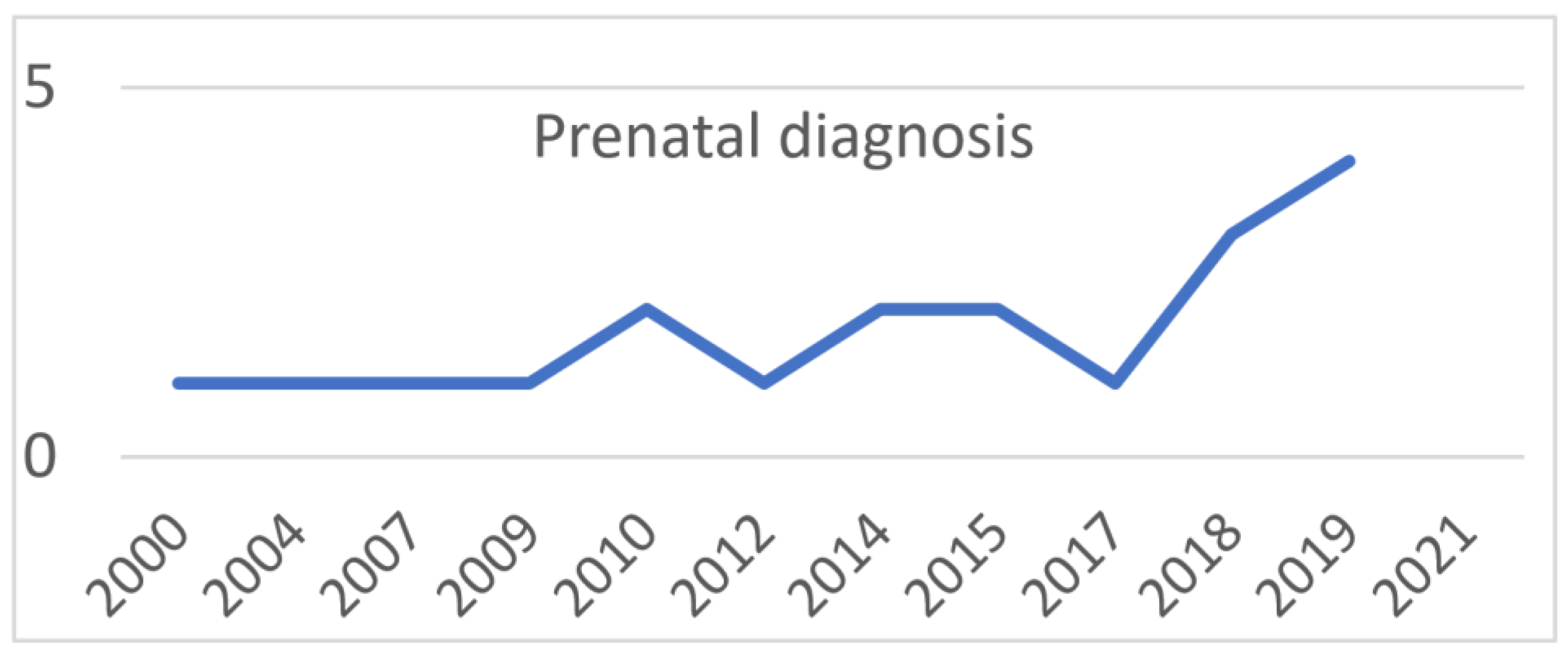

1. Introduction

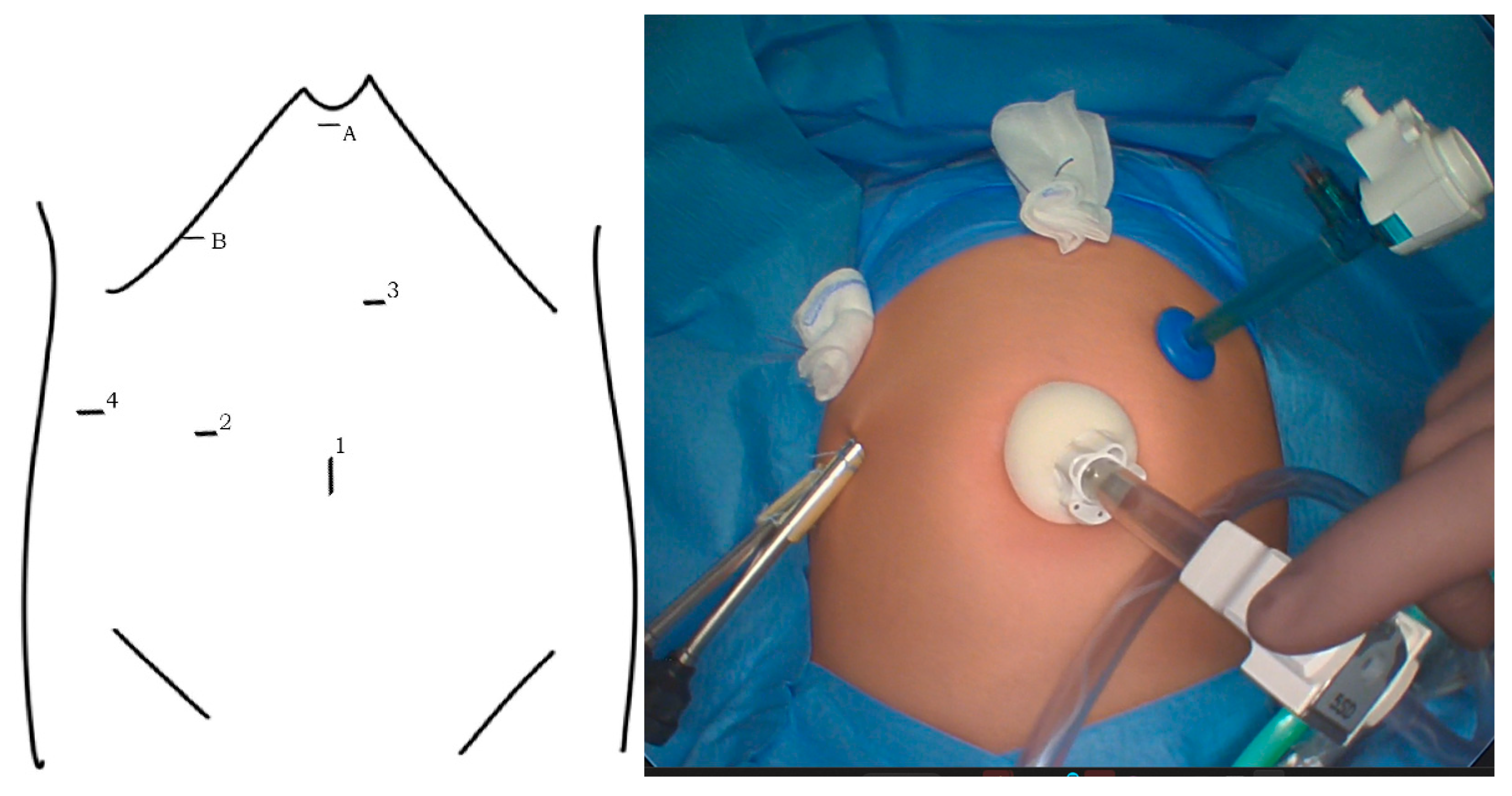

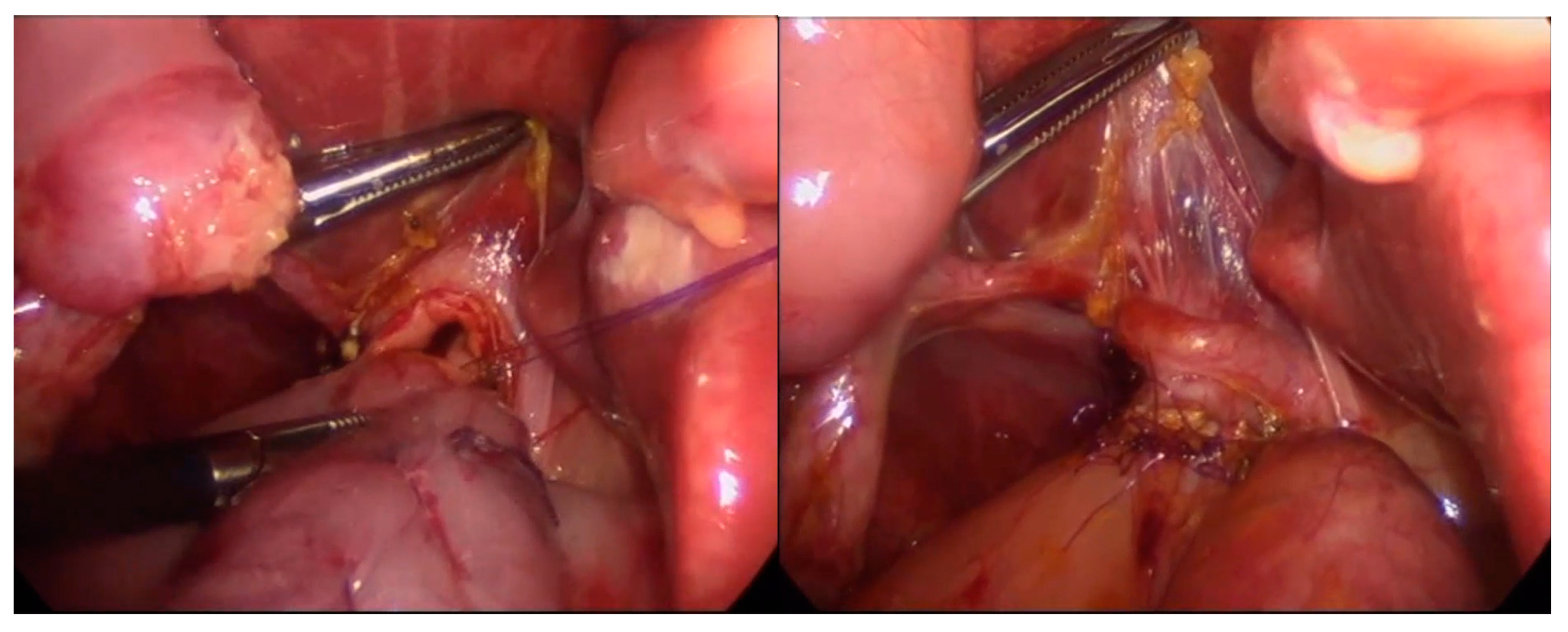

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bancroft, J.D.; Bucuvalas, J.C.; Ryckman, F.C.; Dudgeon, D.L.; Saunders, R.C.; Schwarz, K.B. Antenatal diagnosis of choledochal cyst. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1994, 18, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, M.; Li, L.; Cheng, W. Timing of surgery for prenatally diagnosed asymptomatic choledochal cysts: A prospective randomized study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2012, 47, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Sasaki, F.; Ueki, S.; Hirokata, G.; Okuyama, K.; Cho, K.; Todo, S. Postnatal management for prenatally diagnosed choledochal cysts. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004, 39, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Hove, A.; de Meijer, V.E.; Hulscher, J.B.F.; de Kleine, R.H.J. Meta-analysis of risk of developing malignancy in congenital choledochal malformation. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, H.; Shimada, M.; Kamisawa, T.; Fujii, H.; Hamada, Y.; Kubota, M.; Urushihara, N.; Endo, I.; Nio, M.; Taguchi, T.; et al. Japanese clinical practice guidelines for congenital biliary dilatation. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Honda, S.; Miyagi, H.; Kubota, K.C.; Cho, K.; Taketomi, A. Liver fibrosis in prenatally diagnosed choledochal cysts. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 57, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suita, S.; Shono, K.; Kinugasa, Y.; Kubota, M.; Matsuo, S. Influence of age on the presentation and outcome of choledochal cyst. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1999, 34, 1765–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.Y.; Chang, E.Y.; Hong, Y.J.; Park, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Bai, S.J.; Han, S.J. Retrospective assessment of the validity of robotic surgery in comparison to open surgery for pediatric choledochal cyst. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhao, D.; Xie, X.; Wang, W.; Xiang, B. Laparoscopic surgery versus robot-assisted surgery for choledochal cyst excision: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 987789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, M.; Li, L. Pediatric minimal invasive surgery—Bile duct diseases. Ann. Laparosc. Endosc. Surg. 2018, 3, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, J.; Zhong, W.; Yu, J. Timing of operation in children with a prenatal diagnosis of choledochal cyst: A single-center retrospective study. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Sci. 2022, 29, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.Y.; Wang, H.K.; Yeh, M.L.; Wei, S.H.; Lu, K. Subdural hemorrhage as a first symptom in an infant with a choledochal cyst: Case report. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2012, 9, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumino, S.; Iwai, N.; Deguchi, E.; Shimadera, S.; Iwabuchi, T.; Nishimura, T.; Ono, S. Bleeding tendency as a first symptom in children with congenital biliary dilatation. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2007, 17, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalise, P.N.; Yang, A.; Neumeyer, C.; Perez-Atayde, A.R.; Robinson, J.R.; Kim, H.B.; Cuenca, A.G. Prenatal diagnosis of rapidly enlarging choledochal cyst with gastric outlet obstruction. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 2021, rjab547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.E.; Lancry, K.; Velcek, F.T. Choledochal cyst with perforation--an unusual presentation. Case report and review of the literature. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2001, 39, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lal, R.; Agarwal, S.; Shivhare, R.; Kumar, A.; Sikora, S.S.; Kapoor, V.K.; Saxena, R. Management of complicated choledochal cysts. Dig. Surg. 2007, 24, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainaka, T.; Shirota, C.; Sumida, W.; Yokota, K.; Makita, S.; Amano, H.; Okamoto, M.; Takimoto, A.; Kano, Y.; Yasui, A.; et al. Laparoscopic definitive surgery for choledochal cyst is performed safely and effectively in infants. J. Minim. Access Surg. 2022, 18, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, C.L.; Peters, A.W.; Stratigis, J.D.; Barone, P.D.; Kadenhe-Chiweshe, A.V.; Oh, P.S. Cystic biliary anomaly in a newborn with features of choledochal cyst and cystic biliary atresia. J. Pediatr. Surg. Case Rep. 2021, 66, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessier, M.E.M.; Shneider, B.L. 60 Days in Biliary Atresia: A Historical Dogma Challenged. Clin. Liver Dis. 2020, 15, S3–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, K.C.; Kim, Y.; Spolverato, G.; Maithel, S.; Bauer, T.W.; Marques, H.; Sobral, M.; Knoblich, M.; Tran, T.; Aldrighetti, L.; et al. Presentation and Clinical Outcomes of Choledochal Cysts in Children and Adults: A Multi-institutional Analysis. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schukfeh, N.; Abo-Namous, R.; Madadi-Sanjani, O.; Uecker, M.; Petersen, C.; Ure, B.M.; Kuebler, J.F. The Role of Laparoscopic Treatment of Choledochal Malformation in Europe: A Single-Center Experience and Review of the Literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 32, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, S.Q.; Cao, G.Q.; Li, S.; Guo, J.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, S.T. Outcomes in robotic versus laparoscopic-assisted choledochal cyst excision and hepaticojejunostomy in children. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 5009–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Huang, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, D.; Fang, Y. Outcomes and comparations of pediatric surgery about choledochal cyst with robot-assisted procedures, laparoscopic procedures, and open procedures: A meta-analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 968960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaraviputh, T.; Trakarnsanga, A.; Suksamanapun, N. Robot-assisted complete excision of choledochal cyst type I, hepaticojejunostomy and extracorporeal Roux-en-y anastomosis: A case report and review literature. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, A. Comparative clinical study of laparoscopic and open surgery in children with choledochal cysts. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Do, D.H.; Nguyen, H.V.; Vu, T.H.; Hong, Q.Q.; Vo, C.T.; Dang, T.H.T.; Nguyen, N.B.; Le, D.T.; Tran, P.H.; et al. Treatment of complex complications after choledochal cyst resection by multiple minimal invasive therapies: A case report. Int J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 73, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Moon, S.H.; Park, D.H.; Lee, S.S.; Seo, D.W.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, S.K. Course of choledochal cysts according to the type of treatment. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Kaneko, K.; Ito, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Seo, T.; Harada, T.; Ito, F.; Nagaya, M.; Sugito, T. Complete excision of the intrapancreatic portion of choledochal cysts. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1996, 183, 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Yoshida, K.; Shirai, Y.; Sato, N.; Kashima, Y.; Coutinho, D.S.; Koyama, S.; Muto, T.; Yamagiwa, I.; Iwafuchi, M.; et al. A case of carcinoma arising in the intrapancreatic terminal choledochus 12 years after primary excision of a giant choledochal cyst. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1986, 81, 378–384. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, M.; Li, L.; Cheng, W. Is it necessary to ligate distal common bile duct stumps after excising choledochal cysts? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2011, 27, 829–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Asymptomatic n = 22 | Symptomatic n = 37 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median; range) | 75 days; 14–331 days | 132 days; 11–346 days | =0.48 |

| Sex (male; no.; %) | 5 (23%) | 10 (27%) | =0.71 |

| Body weight (median; range) | 4.9 kg; 3.1–10 kg | 6 kg; 0.8–10.5 kg | =0.77 |

| Total bilirubin mg/dL (median; range) | 0.6; 0.1–9.6 | 7.4; 0.1–19.8 | =0.002 |

| ALT U/l (median; range) | 21; 7–116 | 82; 18–452 | <0.0001 |

| GGTP U/l (median; range) | 120; 16–470 | 315; 13–2166 | =0.037 |

| Time from diagnosis to operation | 75 days; 9–325 days | 26 days; 2–318 days | =0.14 |

| Early complications (no.; %) | 3 (14%) | 5 (13%) | =0.99 |

| Late complications (no.; %) | 1 (4%) | 6 (16%) | =0.18 |

| Prenatal n = 20 | Postnatal n = 39 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median; range) | 60 days; 11–331 days | 152 days; 19–346 days | =0.03 |

| Sex (male; no.; %) | 2 (10%) | 13 (33%) | =0.07 |

| Body weight (median; range) | 4.5 kg; 0.8–10.5 kg | 6.35 kg; 3.1–10 kg | =0.35 |

| Total bilirubin mg/dL (median; range) | 5; 0.2–19.8 | 4; 0.1–18 | =0.87 |

| ALT U/l (median; range) | 29; 7–197 | 68; 17–452 | =0.02 |

| GGTP U/l (median; range) | 336; 16–983 | 223; 13–2166 | =0.95 |

| Early complications (no.; %) | 4 (20%) | 4 (10%) | =0.30 |

| Late complications (no.; %) | 2 (10%) | 5 (13%) | =0.75 |

| Symptomatic preoperative course | 8 (40%) | 29 (74%) | =0.0098 |

| All Patients n = 59 | |

|---|---|

| Early complications | 8 (13%) |

| Bile leak | 6 (10%) |

| Bleeding | 2 (3%) |

| Ileus | 2 (3%) |

| Late complications | 7 (12%) |

| Cholangitis | 7 (12%) |

| Cholelithiasis | 2 (3%) |

| Open n = 41 | Laparoscopic n = 18 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median; range) | 113 days; 11–346 | 130 days; 11–331 | =0.74 |

| Body weight (median; range) | 5.5 kg; 0.8–10.5 kg | 6.45 kg; 3.4–9.6 kg | =0.9 |

| Sex (male; no.; %) | 11 (27%) | 4 (22%) | =0.71 |

| Total bilirubin mg/dL (median; range) | 3; 0,1–18 | 6.9; 0,2–20 | =0.70 |

| ALT U/l (median; range) | 71; 14–452 | 33; 7–144 | =0.1 |

| GGTP U/l (median; range) | 312; 13–2166 | 174; 16–1020 | =0.35 |

| Operating time (median; range) | 207; 170–290 | 222; 135–340 | =0.94 |

| Hospitalization days (median; range) | 10; 8–20 | 8; 6–17 | =0.029 |

| Follow-up in years (median; range) | 6.2; 0.3–18 | 2.6; 1.4–6 | =0.008 |

| Preoperative symptoms (no.; %) | 28 (68%) | 9 (50%) | =0.18 |

| Jaundice | 20 (49%) | 9 (50%) | =0.93 |

| Acholic stools | 14 (34%) | 5 (28%) | =0.63 |

| Vomiting | 4 (10%) | 1 (5%) | =0.59 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) | =0.91 |

| Epigastric resistance | 3 (7%) | 1 (5%) | =0.80 |

| Early complications (no.; %) | 7 (17%) | 1 (6%) | =0.23 |

| Bile leak | 5 (12%) | 1 (6%) | =0.44 |

| Bleeding | 1 (2%) | 0 | =0.5 |

| Ileus | 1 (2%) | 1 (6%) | =0.54 |

| Late complications (no.; %) | 7 (17%) | 0 | =0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kowalski, A.; Kowalewski, G.; Kaliciński, P.; Pankowska-Woźniak, K.; Szymczak, M.; Ismail, H.; Stefanowicz, M. Choledochal Cyst Excision in Infants—A Retrospective Study. Children 2023, 10, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020373

Kowalski A, Kowalewski G, Kaliciński P, Pankowska-Woźniak K, Szymczak M, Ismail H, Stefanowicz M. Choledochal Cyst Excision in Infants—A Retrospective Study. Children. 2023; 10(2):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020373

Chicago/Turabian StyleKowalski, Adam, Grzegorz Kowalewski, Piotr Kaliciński, Katarzyna Pankowska-Woźniak, Marek Szymczak, Hor Ismail, and Marek Stefanowicz. 2023. "Choledochal Cyst Excision in Infants—A Retrospective Study" Children 10, no. 2: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020373

APA StyleKowalski, A., Kowalewski, G., Kaliciński, P., Pankowska-Woźniak, K., Szymczak, M., Ismail, H., & Stefanowicz, M. (2023). Choledochal Cyst Excision in Infants—A Retrospective Study. Children, 10(2), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020373