Palliative and End-of-Life Care Conversations with Older People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Croatia—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

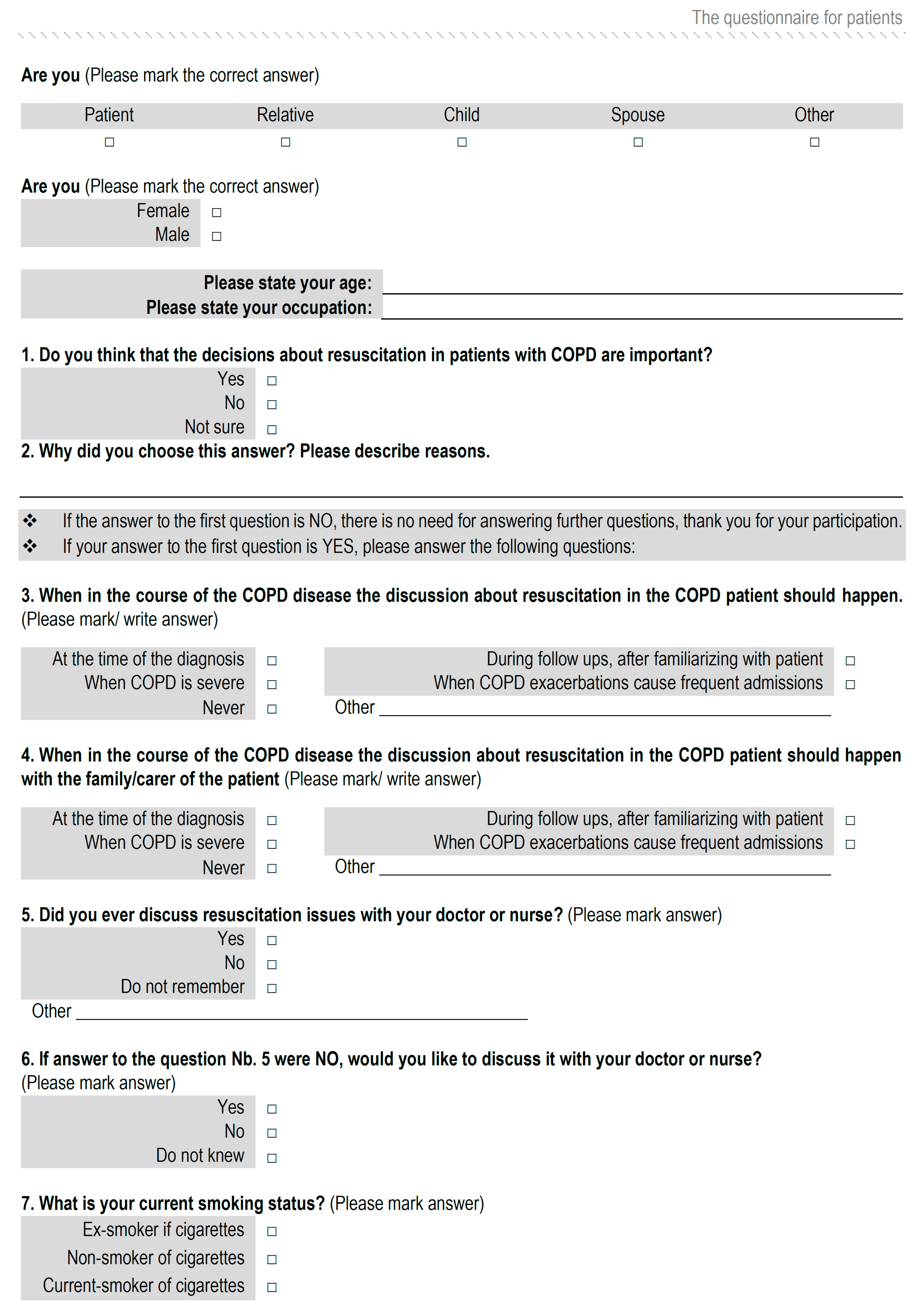

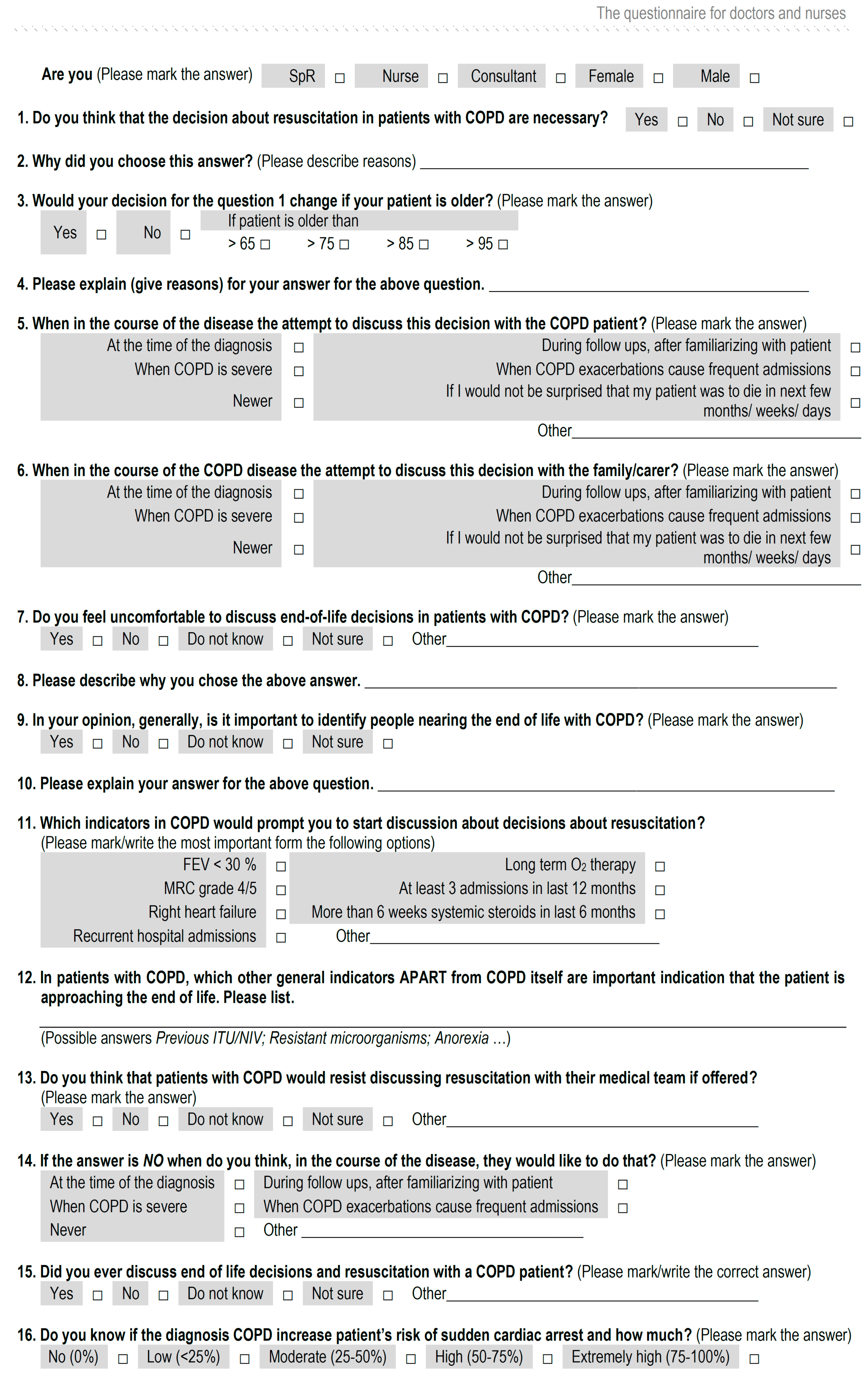

2. Materials and Methods

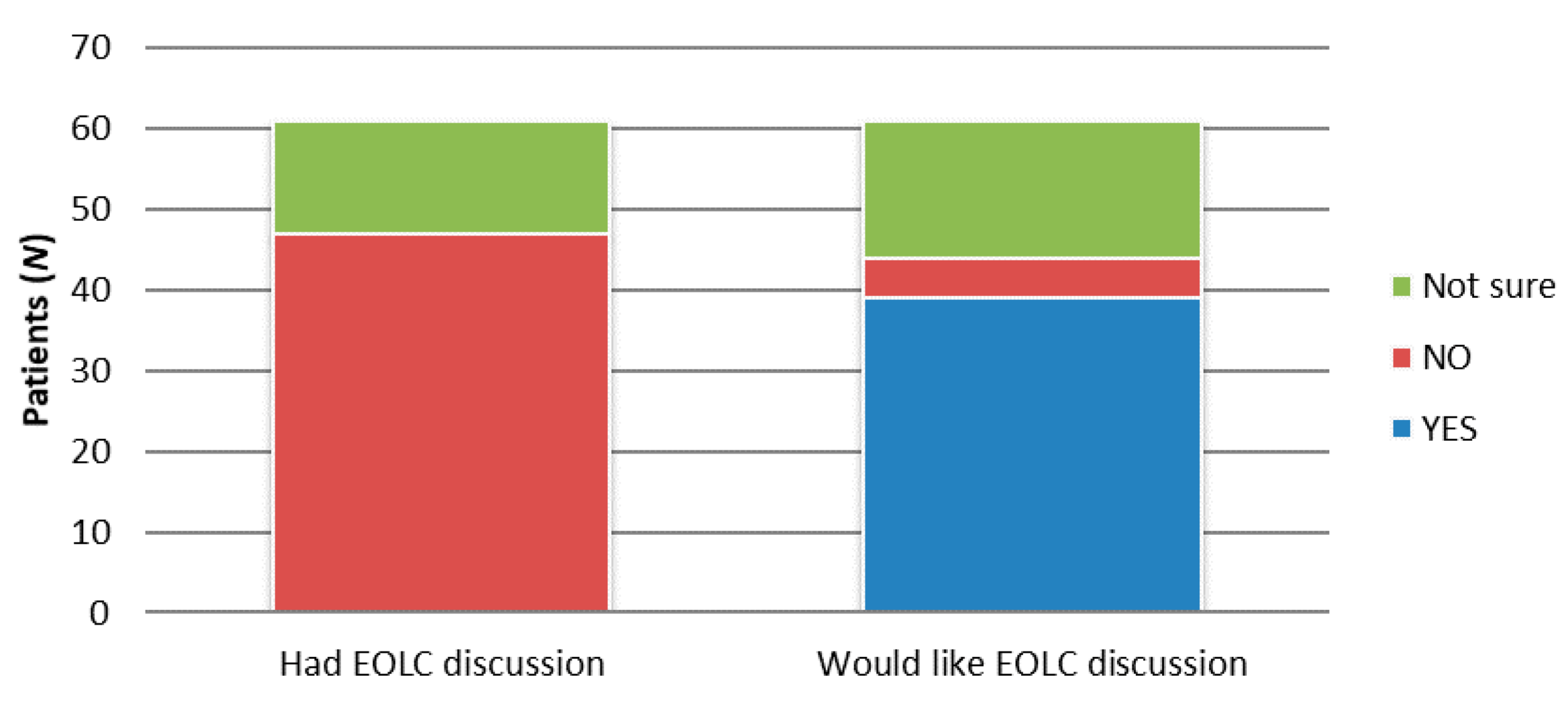

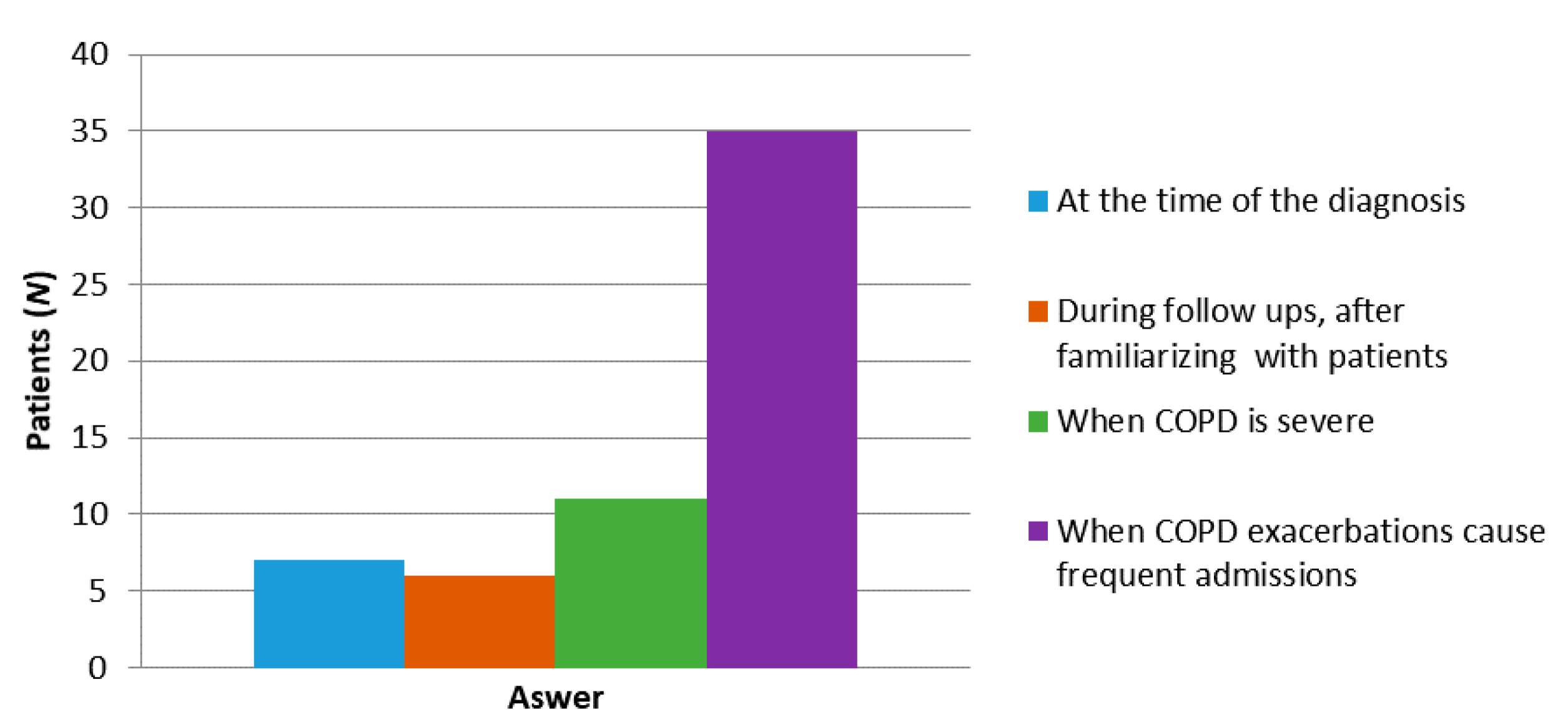

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, B.A.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.-W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016–40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017; IHME: Seattle, WA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, J.; Ely, E.W.; Zhong, Z.; McNiff, K.L.; Dawson, N.V.; Connors, A.F.; Desbiens, N.A.; Claessens, M.; McCarthy, E.P. Living and dying with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, S91–S100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, J.; Engelberg, R.; Nielsen, E.; Au, D.; Patrick, D.; Rybicki, B.; Maliarik, M.; Poisson, L.; Iannuzzi, M. Patient-physician communication about end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2004, 24, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, J.R. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 32, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, P.; Karlsen, S.; Khan, S.; Addington-Hall, J. A comparison ofthe palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat. Med. 2001, 15, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, H.; White, P.T.; Higgs, R.; Pettinari, C.J. GPs’ views of discussions of prognosis in severe COPD. Fam. Pract. 2001, 18, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gott, M.; Gardiner, C.; Small, N.; Payne, S.A.; Seamark, D.; Barnes, S.; Halpin, D.; Ruse, C. Barriers to advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat. Med. 2009, 23, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, M.T.; Lynn, J.; Zhong, Z.; Desbiens, N.A.; Phillips, R.S.; Wu, A.W.; Harrell, F.E.; Connors, A.F. Dying with lung cancer or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2000, 48, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A. Respiratory practitioners’ experience of end-of-life discussions in COPD. Br. J. Nurs. 2010, 19, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.M.; Brophy, C.J.; Greenstone, M. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 2000, 55, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, J.P.; Gomes, B.; Higginson, I.J. A Comparison of Symptom Prevalence in Far Advanced Cancer, AIDS, Heart Disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Renal Disease. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2006, 31, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaHousse, L.; Niemeijer, M.N.; Berg, M.E.V.D.; Rijnbeek, P.R.; Joos, G.F.; Hofman, A.; Franco, O.H.; Deckers, J.W.; Eijgelsheim, M.; Stricker, B.H.; et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sudden cardiac death: The Rotterdam study. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Health Promot. Pract. 2015, 16, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masero, O.I.; Carmona-Rega, I.M.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Ortiz-Amo, R.; Cabrera-Troya, J.; Ortega-Galán, Á.M. Communicating Health Information at the End of Life: The Caregivers’ Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnik, S.; Kanekar, A. Ethical Issues Surrounding End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Health 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Risease-2020 Report; GOLD: Fontana, WI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson, H.M. Evaluation of a mental test score for assessment of mental impairment in the elderly. Age Ageing 1972, 1, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, N.; Jarrett, N.; Hunt, K.; Wilkinson, T. Palliative and end-of-life care conversations in COPD: A systematic literature review. ERJ Open Res. 2017, 3, 68–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, J.E. Advance care planning in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Barriers and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2011, 17, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M. End-of-Life Decision-Making: Special Considerations in the COPD Patient. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/722309 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Momen, N.; Hadfield, P.; Kuhn, I.; Smith, E.; Barclay, S. Discussing an uncertain future: End-of-life care conversations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis. Thorax 2012, 67, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnock, H.; Kendall, M.; Murray, S.A.; Worth, A.; Levack, P.; Porter, M.; MacNee, W.; Sheikh, A. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011, 342, d142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Flaschen, J. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The last year of life. Respir. Care 2004, 49, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gysels, M.; Higginson, I.J. The Experience of Breathlessness: The Social Course of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaber, A.K.; Barnett, M.; Planchant, Y.; McGavin, C.R. Attitudes of 100 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to artificial ventilation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Palliat. Med. 2004, 18, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, J.R.; Wenrich, M.D.; Carline, J.D.; Shannon, S.E.; Ambrozy, D.M.; Ramsey, P.G. Patients’ Perspectives on Physician Skill in End-of-Life Care. Chest 2002, 122, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | N | % | Mean (SD) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||||

| Age | |||||

| Female | 19 | 31.1 | 75.2 (5.1) | 67 | 86 |

| Male | 42 | 68.9 | 74.8 (4.8) | 66 | 85 |

| Total | 61 | 100.0 | 75.0 (5.1) | 66 | 86 |

| Education | |||||

| Elementary school | 28 | 45.9 | |||

| High school | 30 | 49.2 | |||

| Higher education | 3 | 4.9 | |||

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Current smoker | 16 | 26.2 | |||

| Ex-smoker | 45 | 73.8 | |||

| Total | 61 | 100.0 | |||

| Healthcare Providers | |||||

| Professional Level | |||||

| Nurse | 7 | 31.8 | |||

| Specialist registrar | 8 | 36.4 | |||

| Consultant | 7 | 31.8 | |||

| Disease | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Arterial hypertension | 48 | 78.7 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 | 26.2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 | 24.6 |

| Renal insufficiency | 4 | 6.6 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 | 3.3 |

| Characteristics | Value | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPs reports regarding the importance of EOLC discussion | Not important | 5 | 22.7 |

| Important | 17 | 77.3 | |

| Do you discuss these issues with your patients with COPD? | Yes | 3 | 13.6 |

| No | 19 | 86.4 | |

| HPs reports regarding the ideal timing to start EOLC discussions with patients with COPD | At the time of the diagnosis | 2 | 9.1 |

| During follow-ups, after familiarizing with the patient | 2 | 9.1 | |

| When COPD is severe | 9 | 40.9 | |

| When COPD exacerbations cause frequent admissions | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Never | 1 | 4.5 | |

| In your opinion, is it generally important to identify people nearing the end of life with COPD? | Yes | 22 | 100.0 |

| Which indicators in COPD would prompt you to start a discussion about resuscitation? | FEV1 * < 30% | 2 | 9.1 |

| LTOT ** | 3 | 13.6 | |

| RHF *** | 9 | 40.9 | |

| Recurrent hospital admissions | 8 | 36.4 | |

| Do you know whether the diagnosis of COPD increases a patient’s risk of sudden cardiac arrest and by how much? | No risk (0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Low risk (<25%) | 2 | 9.1 | |

| Moderate risk (25–50%) | 12 | 54.5 | |

| High risk (50–75%) | 7 | 31.8 | |

| Extremely high risk (75–100%) | 1 | 4.5 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čičak, P.; Thompson, S.; Popović-Grle, S.; Fijačko, V.; Lukinac, J.; Lukinac, A.M. Palliative and End-of-Life Care Conversations with Older People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Croatia—A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030282

Čičak P, Thompson S, Popović-Grle S, Fijačko V, Lukinac J, Lukinac AM. Palliative and End-of-Life Care Conversations with Older People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Croatia—A Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2020; 8(3):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030282

Chicago/Turabian StyleČičak, Petra, Sanja Thompson, Sanja Popović-Grle, Vladimir Fijačko, Jasmina Lukinac, and Ana Marija Lukinac. 2020. "Palliative and End-of-Life Care Conversations with Older People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Croatia—A Pilot Study" Healthcare 8, no. 3: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030282

APA StyleČičak, P., Thompson, S., Popović-Grle, S., Fijačko, V., Lukinac, J., & Lukinac, A. M. (2020). Palliative and End-of-Life Care Conversations with Older People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Croatia—A Pilot Study. Healthcare, 8(3), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030282