Perceived Impact of Wearable Fitness Trackers on Health Behaviours in Saudi Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Identifying Evidence of Impacts of WFTs

2.1.1. Search Strategy

2.1.2. Eligibility Criteria

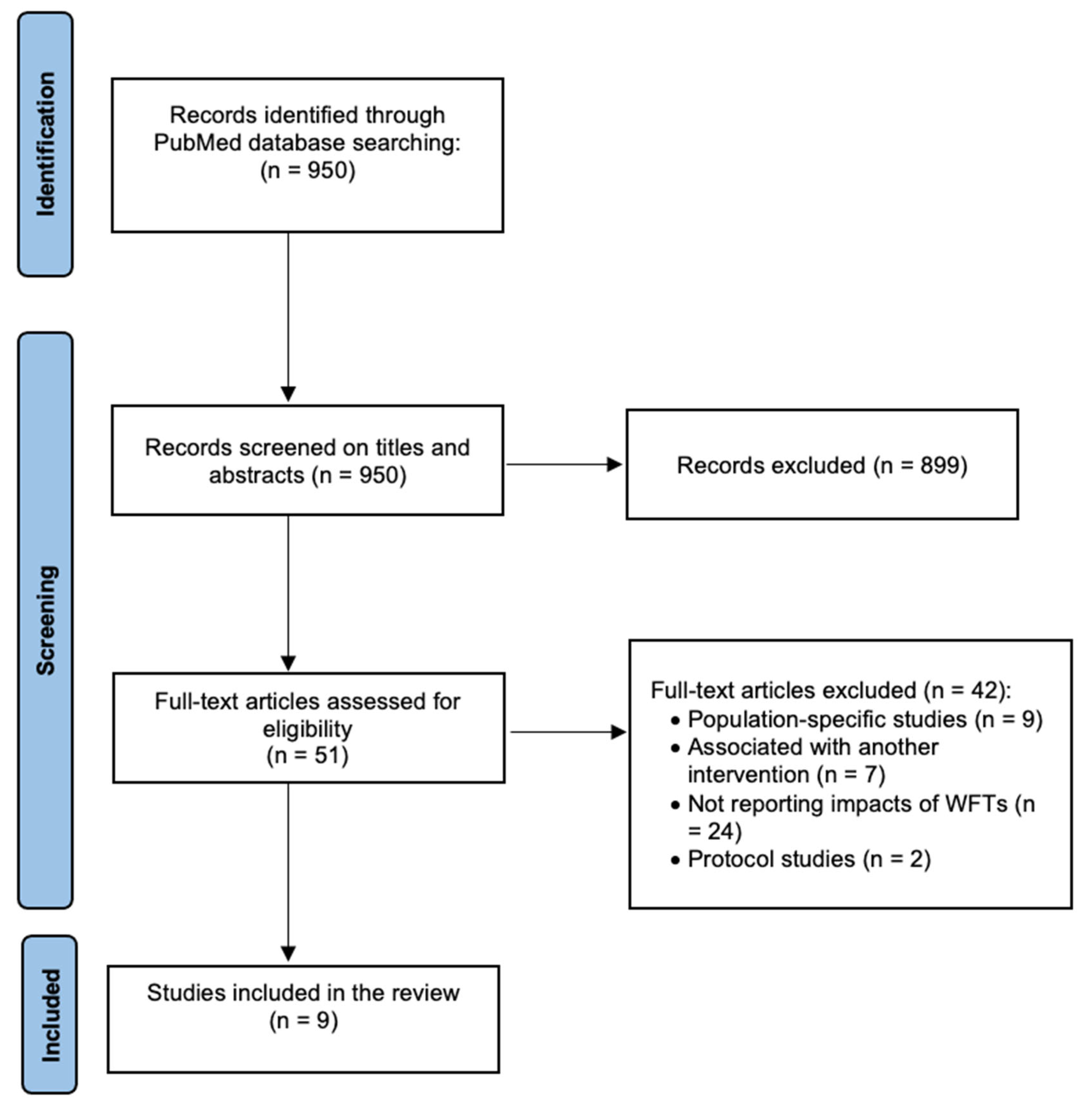

2.1.3. Article Selection

2.1.4. Data Extraction

2.2. Phase 2: Developing an Evidence-Based Questionnaire and Collecting the Data

2.2.1. Questionnaire Structure

- Demographic Information: This section included items on age, gender, and duration and status of wearable fitness tracker use.

- Positive Effects: This section contained nine statements evaluating the perceived benefits of wearable fitness trackers, including increased physical activity, improved health awareness, and enhanced motivation. Participants rated each item using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

- Negative Effects: This section comprises ten items designed to assess potential drawbacks, including stress from constant monitoring and an obsession with health data. These items were also rated on the same five-point Likert scale.

- Open-Ended Question: An open-ended item was included to allow participants to elaborate on their personal beliefs, negative perceived consequences, or experiences with WFTs that the closed-ended items may not have captured.

2.2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1 Results: Systematic Review

3.1.1. Study Selection

3.1.2. Study Characteristics

3.2. Phase 2 Results: Distributed Questionnaire

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.2. Main Questionnaire Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, M.S.; Asch, D.A.; Volpp, K.G. Wearable Devices as Facilitators, Not Drivers, of Health Behavior Change. JAMA 2015, 313, 459–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwek, L.; Ellis, D.A.; Andrews, S.; Joinson, A. The Rise of Consumer Health Wearables: Promises and Barriers. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izu, L.; Scholtz, B.; Fashoro, I. Wearables and Their Potential to Transform Health Management: A Step towards Sustainable Development Goal 3. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datareportal. Digital 2023 Deep-Dive: Global Overview Report. 2023. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-global-overview-report (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Statista. Wearables Unit Shipments Worldwide from 2014 to 2028 (in Millions). 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/437871/wearables-worldwide-shipments/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Pew Research Center. About One-In-Five Americans Use a Smart Watch or Fitness Tracker. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/01/09/about-one-in-five-americans-use-a-smart-watch-or-fitness-tracker/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Yeboah, A.N. The Wearables Market in MEA Region Reached 15 Million Units in 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.techloy.com/mea-wearables-market-2022/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Poirier, J.; Bennett, W.L.; Jerome, G.J.; Shah, N.G.; Lazo, M.; Yeh, H.-C.; Clark, J.M.; Cobb, N.K. Effectiveness of an Activity Tracker- and Internet-Based Adaptive Walking Program for Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, Z.C.; Barr-Anderson, D.J.; Lewis, B.A.; Pereira, M.A.; Gao, Z. Use of Wearable Technology and Social Media to Improve Physical Activity and Dietary Behaviors among College Students: A 12-Week Randomized Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.; Jarrahi, M.H.; Fei, Y.; Karami, A.; Gafinowitz, N.; Byun, A.; Lu, X. Wearable activity trackers, accuracy, adoption, acceptance and health impact: A systematic literature review. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 93, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A.; Muqadas, A.; Akbar, S.; Anwar, S.; Fatima, Q.; Kashif, M. The Impact of Wearable Technology on Athlete Motivation: Enhancing Performance Through Real-Time Feedback. Phys. Educ. Health Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attig, C.; Karp, A.; Franke, T. User Diversity in the Motivation for Wearable Activity Tracking: A Predictor for Usage Intensity? Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Honary, M.; Bell, B.T.; Clinch, S.; EWild, S.; McNaney, R. Understanding the Role of Healthy Eating and Fitness Mobile Apps in the Formation of Maladaptive Eating and Exercise Behaviors in Young People. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Quiroz, J.C.; Tong, H.L.; Bazalar, M.A.; Coiera, E. A Mobile Social Networking App for Weight Management and Physical Activity Promotion: Results From an Experimental Mixed Methods Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazroi, A.A.; Mohammed, F.; Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Hoque, R. An empirical study of factors influencing e-health services adoption among public in Saudi Arabia. Health Inform. J. 2022, 28, 14604582221102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binyamin, S.S.; Hoque, M.R. Understanding the Drivers of Wearable Health Monitoring Technology: An Extension of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaskari, E.; Alanzi, T.; Alrayes, S.; Aljabri, D.; Almulla, S.; Alsalman, D.; Algumzi, A.; Alameri, R.; Alakrawi, Z.; Alnaim, N.; et al. Utilization of wearable smartwatch and its application among Saudi population. Front. Comput. Sci. 2022, 4, 874841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuwais, N.; Alharbi, Z.H. The Effectiveness of Wearable Devices on the Users’ Health: The Case of Saudi Arabia. SAR J.-Sci. Res. 2022, 5, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSayegh, L.A.; Al-Mustafa, M.S.; Alali, A.H.; Farhan, M.F.; AlShamlan, N.A.; AlOmar, R.S. Association between fitness tracker use, physical activity, and general health of adolescents in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2023, 30, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E.R. The Practice of Social Research, 12th ed.; Wadsworth Publishing: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gotzsche, P.C.; AIoannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339, b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Edney, S.; Maher, C. Anxious or empowered? A cross-sectional study exploring how wearable activity trackers make their owners feel. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeppe, S.; Alley, S.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bray, N.A.; Williams, S.L.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjo, L.; Ding, D.; Heleno, B.; Kocaballi, B.; Quiroz, J.C.; Tong, H.L.; Chahwan, B.; Neves, A.L.; Gabarron, E.; Dao, K.P.; et al. Do smartphone applications and activity trackers increase physical activity in adults? Systematic review, meta-analysis and metaregression. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeppe, S.; Salmon, J.; Williams, S.L.; Power, D.; Alley, S.; Rebar, A.L.; Hayman, M.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. Effects of an Activity Tracker and App Intervention to Increase Physical Activity in Whole Families-The Step It Up Family Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Schoefer, K.; Manika, D.; Tzemou, E. The “Dark Side” of General Health and Fitness-Related Self-Service Technologies: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Directions for Future Research. J. Public Policy Mark. 2024, 43, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.; Pandey, S.; Chawla, D. Impact of technology, health and consumer-related factors on continued usage intention of wearable fitness tracking (WFT) devices. Benchmark. Int. J. 2022, 30, 3444–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friel, C.P.; Cornelius, T.; Diaz, K.M. Factors associated with long-term wearable physical activity monitor user engagement. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Method | Impact | Type of Impact | Country | Number of Participants | Gender (% Female) | Average Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Randomised Controlled Trial | Increase in steps. | positive | United States | n = 265 | 66.0% | 39.9 |

| [15] | Mixed-method | Decrease in BMI and increase in daily step counts. | positive | Australia | n = 55 | 51.0% | 23.6 |

| Negative feeling and demotivation from the social comparison with fitter people in the app. | negative | ||||||

| [14] | Mixed-method | (1) guilt formation because of the nature of persuasive models, (2) social isolation as a result of personal regimens around diet and fitness goals, (3) fear of receiving negative responses when targets are not achieved, and (4) feelings of being controlled by the app. | negative | England | n = 117 | 27.4% | 18–25 |

| [23] | Survey | Anxiety or frustration when prevented from wearing their device. | negative | Australia | n = 237 | 72.0% | 33.1 |

| Positive experience for users with little risk of negative psychological consequences. | positive | ||||||

| [10] | Systematic review | Behaviour change towards self-improvement identified from 83 articles including: self-monitoring, goal setting, reinforcement, self-awareness, and self-knowledge, increase physical activity and manage weight. | positive | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [9] | Randomised pilot study | Increase in physical activity and decreased daily caloric intake. Improvement in self-efficacy, social support and intrinsic motivation. | positive | United States | n = 38 | 73.6% | 21.5 |

| [24] | Systematic review | Improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviours. | positive | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [25] | Systematic review and meta-analyses | A small-to-moderate positive effect on physical activity measures. | positive | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [26] | Feasibility study with pre-post intervention measures | Increase in physical activity. | positive | Australia | 130 | 52.3% | 23.7 |

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 96 (62%) |

| Male | 58 (38%) | |

| Age Group (years) | 18–29 | 69 (45%) |

| 30–39 | 30 (20%) | |

| 40–49 | 29 (19%) | |

| 50–59 | 22 (14%) | |

| 60+ | 4 (3%) | |

| WFT Usage Duration/Status | Currently using—<2 months | 21 (14%) |

| Currently using—>2 months | 81 (53%) | |

| No longer using—used <2 months | 24 (16%) | |

| No longer using—used >2 months | 28 (18%) |

| Question No. | Positive Effect Section (M ± SD) | Negative Effect Section (M ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.63 ± 0.98 | 2.53 ± 1.10 |

| 2 | 3.82 ± 1.00 | 1.87 ± 0.93 |

| 3 | 3.75 ± 0.97 | 2.35 ± 1.02 |

| 4 | 3.16 ± 1.10 | 2.44 ± 1.05 |

| 5 | 3.23 ± 1.05 | 2.27 ± 0.98 |

| 6 | 2.67 ± 1.07 | 2.45 ± 0.97 |

| 7 | 2.83 ± 1.02 | 1.63 ± 0.87 |

| 8 | 2.46 ± 0.90 | 1.73 ± 0.86 |

| 9 | 3.78 ± 1.04 | 1.89 ± 0.89 |

| 10 | 2.36 ± 1.11 | |

| Composite Score | 3.26 ± 0.73 | 2.15 ± 0.66 |

| Group (n) | Positive Effects (M ± SD) | Negative Effects (M ± SD) | p-Value (Positive) (95% CI, df) * | p-Value (Negative) (95% CI, df) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 58) | 3.23 ± 0.87 | 2.20 ± 0.66 | 0.34 (−0.20 to 0.32, 94.35) | 0.24 (−0.29 to 0.14, 121.94) |

| Female (n = 96) | 3.28 ± 0.64 | 2.12 ± 0.67 | ||

| 18–29 (n = 69) | 3.23 ± 0.64 | 2.14 ± 0.68 | 0.56 (−0.25 to 0.30, 149) | 0.19 (−0.22 to 0.20, 149) |

| 30–39 (n = 30) | 3.20 ± 0.70 | 2.05 ± 0.65 | ||

| 40–49 (n = 29) | 3.47 ± 0.78 | 2.34 ± 0.54 | ||

| 50–59 (n = 22) | 3.17 ± 0.86 | 2.18 ± 0.73 | ||

| 60+ (n = 4) | 3.19 ± 1.46 | 1.58 ± 0.53 | ||

| Currently using < 2 months (n = 21) | 3.11 ± 0.79 | 2.23 ± 0.73 | 0.01 (−0.10 to 0.16, 150) | 0.51 (−0.27 to 0.32, 150) |

| Currently using > 2 months (n = 81) | 3.43 ± 0.66 | 2.14 ± 0.70 | ||

| No longer using < 2 months (n = 24) | 2.93 ± 0.67 | 2.28 ± 0.56 | ||

| No longer using > 2 months (n = 28) | 3.16 ± 0.85 | 2.03 ± 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abahussin, A.A. Perceived Impact of Wearable Fitness Trackers on Health Behaviours in Saudi Adults. Healthcare 2026, 14, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010126

Abahussin AA. Perceived Impact of Wearable Fitness Trackers on Health Behaviours in Saudi Adults. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbahussin, Asma A. 2026. "Perceived Impact of Wearable Fitness Trackers on Health Behaviours in Saudi Adults" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010126

APA StyleAbahussin, A. A. (2026). Perceived Impact of Wearable Fitness Trackers on Health Behaviours in Saudi Adults. Healthcare, 14(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010126