Changes in Hedonic Hunger and Problematic Eating Behaviors Following Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Study of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

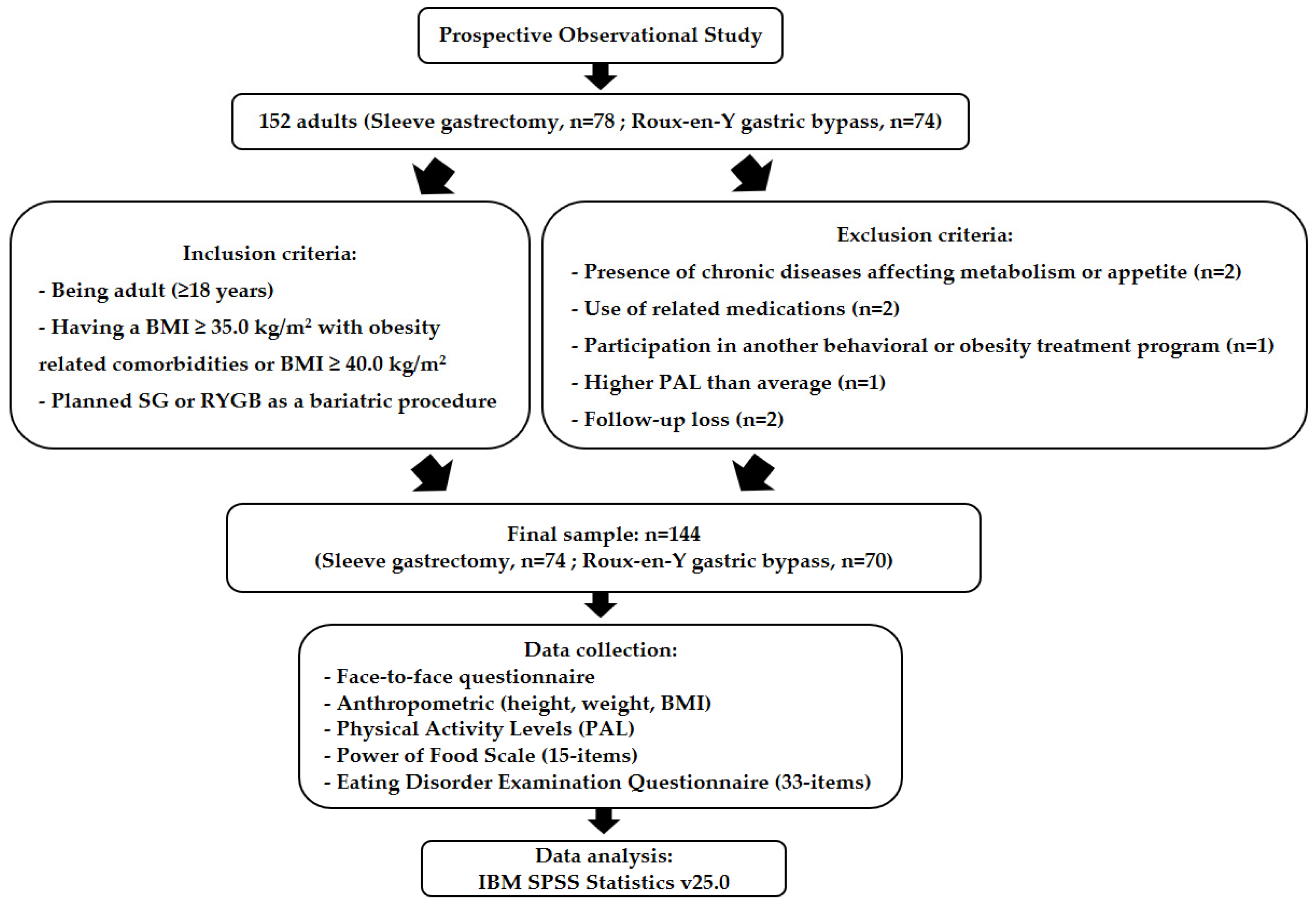

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants and Procedures

2.2. Data Collection Process

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic, Anthropometric, and Physical Activity Assessments

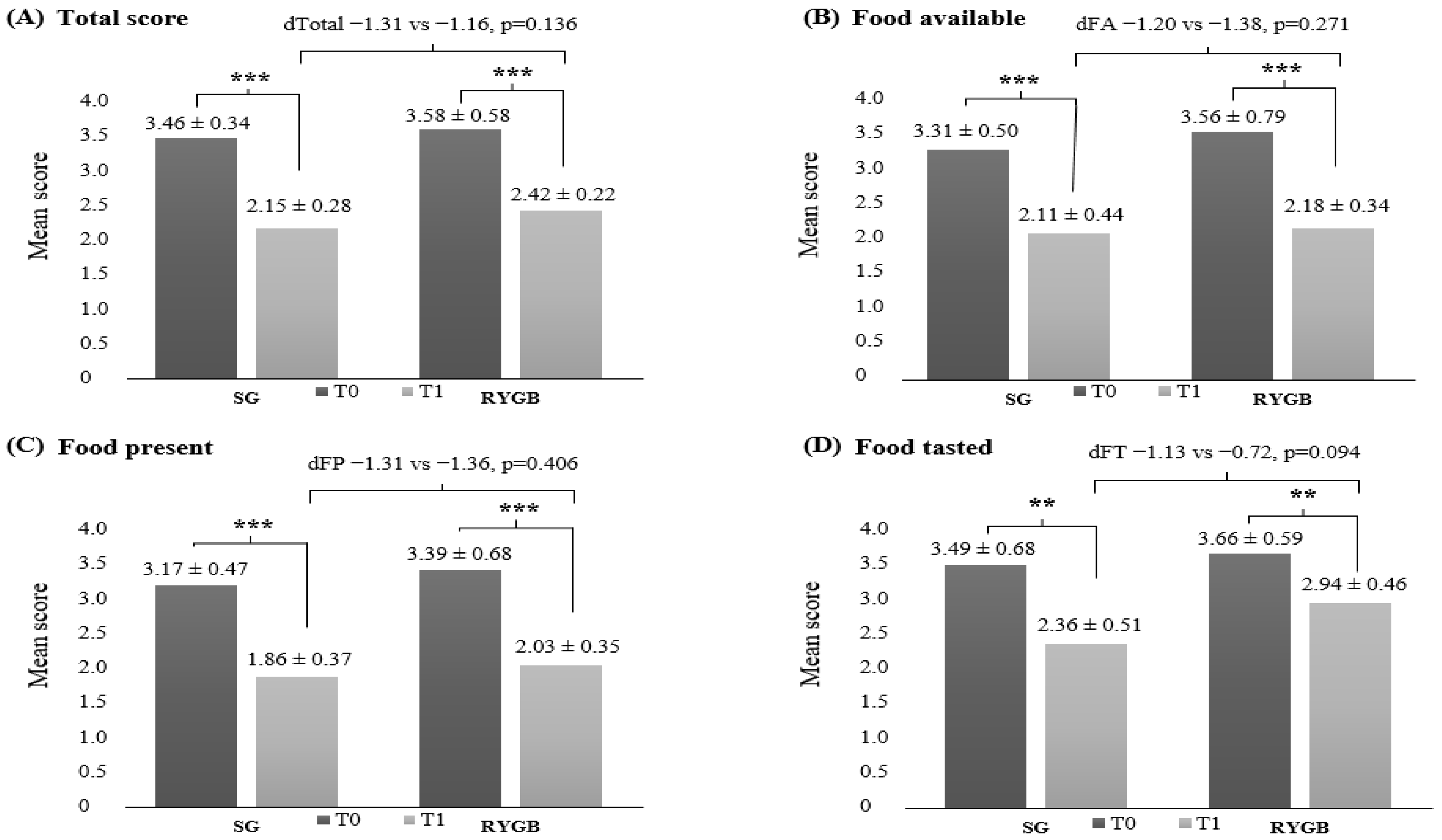

2.3.2. Hedonic Hunger

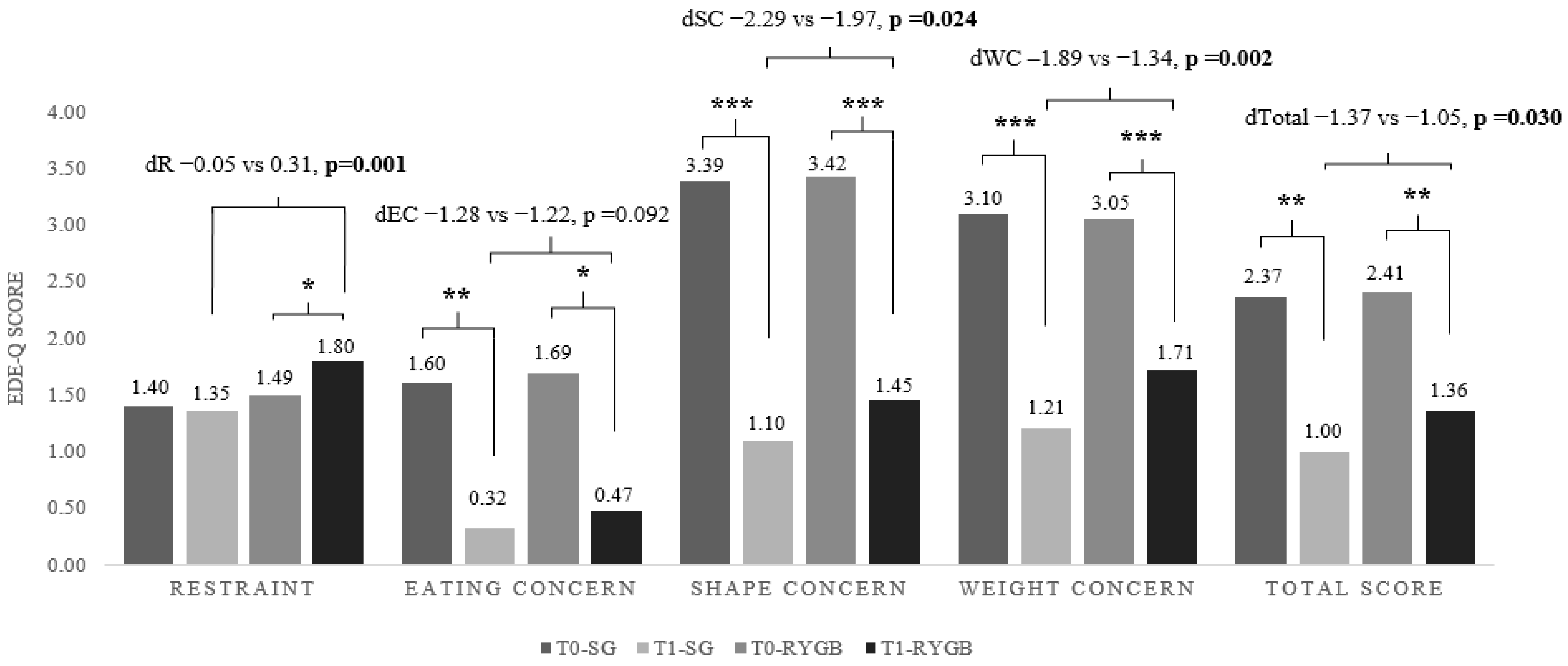

2.3.3. Problematic Eating Behaviors

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SG | Sleeve gastrectomy |

| RYGB | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| PYY | peptide-YY |

| ED | Eating disorder |

| PEBs | Problematic eating behaviors |

| %TWL | Percent total weight loss |

| PAL | Physical activity Level |

| PFS | Power of Food Scale |

| EDE-Q | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire |

| T0 | Baseline, one week before surgery |

| T1 | 24 weeks after surgery |

| BW | Body weight |

References

- Schauer, P.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Kirwan, J.P.; Wolski, K.; Aminian, A.; Brethauer, S.A.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Singh, R.P.; Pothier, C.E.; Nissen, S.E.; et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.D.; Davidson, L.E.; Litwin, S.E.; Kim, J.; Kolotkin, R.L.; Nanjee, M.N.; Gutierrez, J.M.; Frogley, S.J.; Ibele, A.R.; Brinton, E.A.; et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1143–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrisani, L.; Santonicola, A.; Iovino, P.; Vitiello, A.; Higa, K.; Himpens, J.; Buchwald, H.; Scopinaro, N. IFSO worldwide survey 2016: Primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3783–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterli, R.; Steinert, R.E.; Woelnerhanssen, B.; Peters, T.; Christoffel-Courtin, C.; Gass, M.; Kern, B.; Von-Fluee, M.; Beglinger, C. Metabolic and hormonal changes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Ygastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: A randomized, prospective trial. Obes. Surg. 2012, 22, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, P.; Helmiö, M.; Ovaska, J.; Juuti, A.; Leivonen, M.; Peromaa-Haavisto, P.; Hurme, S.; Soinio, M.; Nuutila, P.; Victorzon, M. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: The SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingrone, G.; Panunzi, S.; De Gaetano, A.; Guidone, C.; Iaconelli, A.; Leccesi, L.; Nanni, G.; Pomp, A.; Castagneto, M.; Ghirlanda, G.; et al. Bariatric surgery versus conventional medical therapy for type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, J.; Frank, L.; Rabena, R.; Craggs-Dino, L.; Isom, K.A.; Greiman, L. American society for metabolic and bariatric surgery integrated health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient 2016 update: Micronutrients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. Evaluating the effectiveness and long-term outcomes of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs gastric sleeve bariatric surgery in obese and diabetic patients: Systematic review. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2025, 241, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaher, O.; Wollenhaupt, F.; Croner, R.S.; Hukauf, M.; Stroh, C. Evaluation of the effect of sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with morbid obesity: Multicenter comparative study. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2024, 409, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zeng, N.; Liu, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhang, S.; Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Han, J.; et al. The choice of gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy for patients stratified by diabetes duration and body mass index (BMI) level: Results from a national registry and meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3975–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, H.; Ivanics, T.; Carlin, A.M. Factors influencing the choice between laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Endosc. 2021, 35, 4691–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y.; Balakrishnan, P.; Kuno, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Bowles, M.; Takagi, H.; Denning, D.A.; Nease, D.B.; Kindel, T.L.; Munie, S. Comparative survival of sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adults with obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2025, 21, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winckelmann, L.A.; Gribsholt, S.B.; Madsen, L.R.; Richelsen, B.; Svensson, E.; Jørgensen, N.B.; Kristiansen, V.B.; Pedersen, S.B. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy: Nationwide data from the Danish quality registry for treatment of severe obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2022, 18, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.S.; Christensen, B.J.; Ritz, C.; Rasmussen, S.; Hansen, T.T.; Bredie, W.L.P.; le Roux, C.W.; Sjödin, A.; Schmidt, J.B. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy does not affect food preferences when assessed by an ad libitum buffet meal. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 2599–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; De Giuseppe, R.; Biino, G.; Persico, F.; Ciliberto, A.; Alessandro, G.; Stanford, F.C. Evaluation of eating habits and lifestyle in patients with obesity before and after bariatric surgery: A single Italian center experience. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, K.; Eagon, J.C.; Klein, S.; Pepino, M.Y. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on eating behavior and sweet taste perception in subjects with obesity. Nutrients 2018, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qanaq, D.; O’Keeffe, M.; Cremona, S.; Bernardo, W.M.; Mclntyre, R.D.; Papada, E.; Benkalkar, S.; Rubino, F. The role of dietary intake in the weight loss outcomes of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 3021–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergenç, M.; Uprak, T.K.; Feratoğlu, H.; Günal, Ö. The impact of preoperative eating habits on weight loss after metabolic bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2025, 35, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaronidis, J.M.; Pucci, A.; Adamo, M.; Jenkinson, A.; Elkalaawy, M.; Batterham, R.L. Impact of sleeve gastrectomy compared to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass upon hedonic hunger and the relationship to post-operative weight loss. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 2031–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultes, B.; Ernst, B.; Wilms, B.; Thurnheer, M.; Hallschmid, M. Hedonic hunger is increased in severely obese patients and is reduced after gastric bypass surgery. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelleri, J.C.; Bushmakin, A.G.; Gerber, R.A.; Leidy, N.K.; Sexton, C.C.; Karlsson, J.; Lowe, M.R. Evaluating the Power of Food Scale in obese subjects and a general sample of individuals: Development and measurement properties. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barstad, L.H.; Johnson, L.K.; Borgeraas, H.; Hofsø, D.; Svanevik, M.; Småstuen, M.C.; Hertel, J.K.; Hjelmesæth, J. Changes in dietary intake, food tolerance, hedonic hunger, binge eating problems, and gastrointestinal symptoms after sleeve gastrectomy compared with after gastric bypass; 1-year results from the Oseberg study—A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, E.; Dougkas, A.; Nazare, J.; Bagot, S.; Disse, E.; Iceta, S. A systematic review and meta-analyses of food preference modifications after bariatric surgery. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opozda, M.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Wittert, G. Changes in problematic and disordered eating after gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding and vertical sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic review of pre-post studies. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 770–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Faulconbridge, L.F.; Jones-Corneille, L.R.; Sarwer, D.B.; Fabricatore, A.N.; Thomas, J.G.; Wilson, G.T.; Alexander, M.G.; Pulcini, M.E.; Webb, V.L.; et al. Binge eating disorder and the outcome of bariatric surgery at one year: A prospective, observational study. Obesity 2011, 19, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweiger, C.; Weiss, R.; Keidar, A. Effect of different bariatric operations on food tolerance and quality of eating. Obes. Surg. 2010, 20, 1393–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, M.; Calmes, J.M.; Paroz, A.; Giusti, V. A new questionnaire for quick assessment of food tolerance after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2007, 17, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.A.; Overs, S.E.; Zarshenas, N.; Walton, K.L.; Jorgensen, J.O. Food tolerance and diet quality following adjustable gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, e183–e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluzzi, I.; Raparelli, L.; Guarnacci, L.; Paone, E.; Del Genio, G.; Le Roux, C.W.; Silecchia, G. Food intake and changes in eating behavior after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 2059–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Najim, W.; Docherty, N.G.; Le Roux, C.W. Food intake and eating behavior after bariatric surgery. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1113–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Labban, S.; Safadi, B.; Olabi, A. The effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy surgery on dietary intake, food preferences, and gastrointestinal symptoms in post-surgical morbidly obese lebanese subjects: A cross-sectional pilot study. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 2393–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, B.D.M.; Earthman, C.P.; Farias, G.; Masquio, D.C.L.; Clemente, A.P.G.; Peixoto, P.; Bettini, S.C.; von Der Heyde, M.E.; Damaso, A.R. Eating patterns and food choice as determinant of weight loss and improvement of metabolic profile after RYGB. Nutrition 2017, 33, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullrich, J.; Ernst, B.; Wilms, B.; Thurnheer, M.; Schultes, B. Roux-en Y gastric bypass surgery reduces hedonic hunger and improves dietary habits in severely obese subjects. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenius, A.; Larsson, I.; Melanson, K.J.; Lindroos, A.K.; Lönroth, H.; Bosaeus, I.; Olbers, T. Decreased energy density and changes in food selection following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaronidis, J.M.; Neilson, S.; Cheung, W.H.; Tymoszuk, U.; Pucci, A.; Finer, N.; Doyle, J.; Hashemi, M.; Elkalaawy, M.; Adamo, M.; et al. Reported appetite, taste and smell changes following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: Effect of gender, type 2 diabetes and relationship to post-operative weight loss. Appetite 2016, 107, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamplekou, E.; Komesidou, V.; Bissias, C.H.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Melissas, J. Psychological condition and quality of life in patients with morbid obesity before and after surgical weight loss. Obes. Surg. 2005, 15, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, C.; Widermann, C.; Harms, D.; Leiberich, P.L.; Tritt, K.; Kettler, C.; Lahmann, C.; Rother, W.K.; Loew, T.H.; Nickel, M.K. Patients with extreme obesity: Change in mental symptoms three years after gastric banding. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2005, 35, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.M.; Utzinger, L.M.; Pisetsky, E.M. Eating disorders and problematic eating behaviours before and after bariatric surgery: Characterization, assessment and association with treatment outcomes. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizato, N.; Botelho, P.B.; Gonçalves, V.S.; Dutra, E.S.; de Carvalho, K.M. Effect of grazing behavior on weight regain post-bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Allison, K.C.; Wadden, T.A.; Ashare, R.; Spitzer, J.C.; Mc Cuen-Wurst, C.; LaGrotte, C.; Williams, N.N.; Edwards, M.; Tewksbury, C. Psychopathology, disordered eating, and impulsivity as predictors of outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M.J.; King, W.C.; Kalarchian, M.A.; White, G.E.; Marcus, M.D.; Garcia, L.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Mitchell, J.E. Eating pathology and experience and weight loss in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 3-year follow-up. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, K.W.; Martin-Fernandez, J.; Marek, R.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Heinberg, L.J. Associations among psychopathology and eating disorder symptoms and behaviors in post-bariatric surgery patients. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 2545–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.; Mitchell, J.E.; Vaz, A.R.; Bastos, A.P.; Ramalho, S.; Silva, C.; Cao, L.; Brandao, I.; Machado, P.P.P. The presence of maladaptive eating behaviors after bariatric surgery in a cross sectional study: Importance of picking or nibbling on weight regain. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, S.; Belligoli, A.; Fabris, R.; Busetto, L. Diet approach before and after bariatric surgery. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtz, S.; Miras, A.D.; Chhina, N.; Prechtl, C.G.; Sleeth, M.L.; Daud, N.M.; Ismail, N.A.; Durighel, G.; Ahmed, A.R.; Olbers, T.; et al. Obese patients after gastric bypass surgery have lower brain-hedonic responses to food than after gastric banding. Gut 2014, 63, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iljin, A.; Wlaźlak, M.; Sitek, A.; Antoszewski, B.; Zieliński, T.; Gmitrowicz, A.; Kropiwnicki, P.; Strzelczyk, J. Mental health, and eating disorders in patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB). Pol. J. Surg. 2024, 96, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Pucci, A.; Batterham, R.L. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Effects on feeding behavior and underlying mechanisms. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, D.S.; Thomas, J.G.; Jones, D.B.; Schumacher, L.M.; Webster, J.; Evans, E.W.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Vithiananthan, S. Ecological momentary assessment of gastrointestinal symptoms and risky eating behaviors in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy patients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nymo, S.; Skjølsvold, B.O.; Aukan, M.; Finlayson, G.; Græslie, H.; Mårvik, R.; Kulseng, B.; Sandvik, J.; Martins, C. Suboptimal weight loss 13 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Is hedonic hunger, eating behaviour and food reward to blame? Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukan, M.I.; Finlayson, G.; Martins, C. Hedonic hunger, eating behavior, and food reward and preferences 1 year after initial weight loss by diet or bariatric surgery. Obesity 2024, 32, 1059–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.; Carter, N.C.; Pucci, A.; Jones, A.; Elkalaawy, M.; Cheung, W.H.; Mohammadi, B.; Finer, N.; Fiennes, A.G.; Hashemi, M.; et al. Age-and sex-specific effects on weight loss outcomes in a comparison of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Obes. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO; UNU. Human Energy Requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. 2001. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y5686e/y5686e00.htm (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Lowe, M.R.; Butryn, M.L. Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiol. Behav. 2007, 91, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehtap, A.O.; Melisa, H. Validation of the Turkish version Power of the Food Scale (PFS) for determining hedonic hunger status and correlate between PFS and body mass index. Malays. J. Nutr. 2020, 26, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergüney Okumuş, F.E.; Sertel Berk, H.Ö.; Yücel, B.; Rieger, E. The anorexia nervosa stages of change questionnaire and the bulimia nervosa stages of change questionnaire: Their psychometric properties in a Turkish sample. Anatol. J. Psychiatry 2018, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, K.A.; Grilo, C.M.; Masheb, R.M.; Rothschild, B.S.; Burke-Martindale, C.H.; Brody, M.L. Comparison of two self-report instruments for assessing binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates. Behav. Res. Therapy 2006, 44, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseth, M.S.; Hanvold, S.E.; Rø, Ø.; Risstad, H.; Mala, T.; Benth, J.Š.; Engström, M.; Olbers, T.; Henjum, S. Self-reported eating disorder symptoms before and after gastric bypass and duodenal switch for super obesity—A 5-year follow-up study. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mond, J.M.; Hay, P.J.; Rodgers, B.; Owen, C. Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for young adult women. Behav. Res. Therapy 2006, 44, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, C.C.; Benoit, S.C.; Peugh, J.L.; Reiter-Purtill, J.; Inge, T.H.; Zeller, M.H. Longitudinal trends in hedonic hunger after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014, 10, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, G.; le Roux, C. Mechanism underlying the weight loss and complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. review. Obes. Surg. 2016, 26, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- le Roux, C.W.; Aylwin, S.J.; Batterham, R.L.; Borg, C.M.; Coyle, F.; Prasad, V.; Sandra, S.; Mohammad, G.; Ameet, P.; Stephen, B. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann. Surg. 2006, 243, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochner, C.N.; Stice, E.; Hutchins, E.; Afifi, L.; Geliebter, A.; Hirsch, J.; Teixeira, J. Relation between changes in neural responsivity and reductions in desire to eat high-calorie foods following gastric bypass surgery. Neuroscience 2012, 209, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, L.; Murty, G.; Bowrey, D.J. Taste, smell and appetite change after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes. Surg. 2014, 24, 1463–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miras, A.; le Roux, C. Mechanisms underlying weight loss after bariatric surgery. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; Papantoni, A.; Veldhuizen, M.G.; Kamath, V.; Harris, C.; Moran, T.H.; Carnell, S.; Steele, K.E. Taste-related reward is associated with weight loss following bariatric surgery. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4370–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkoori, N.; Ibrahim, B.; Shahsavan, M.; Shahmiri, S.S.; Pazouki, A.; Amr, B.; Kermansaravi, M. Alterations in taste preferences one year following sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and one anastomosis gastric bypass: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nance, K.; Acevedo, M.B.; Pepino, M.Y. Changes in taste function and ingestive behavior following bariatric surgery. Appetite 2020, 146, 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Penney, N.; Darzi, A.; Purkayastha, S. Taste changes after bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3321–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, R.; Chong, L.; Hii, M.W.; Brown, R.M.; Sumithran, P. The effect of bariatric surgery on the expression of gastrointestinal taste receptors: A systematic review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2024, 25, 421–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, G.; Godini, L.; Amedei, S.G.; Faravelli, C.; Lucchese, M.; Ricca, V. Psychological effects and outcome predictors of three bariatric surgery interventions: A 1-year follow-up study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2014, 19, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirzadeh, Y.; Kantarovich, K.; Wnuk, S.; Okrainec, A.; Cassin, S.E.; Hawa, R.; Sockalingam, S. Binge eating, loss of control over eating, emotional eating, and night eating after bariatric surgery: Results from the Toronto Bari-PSYCH cohort study. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gero, D.; Tzafos, S.; Milos, G.; Gerber, P.A.; Vetter, D.; Bueter, M. Predictors of a healthy eating disorder examination-questionnaire (EDE-Q) score 1 year after bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışır, S.; Çalışır, A.; Arslan, M.; İnanlı, İ.; Çalışkan, A.M.; Eren, İ. Assessment of depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and eating psychopathology after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: 1-year follow-up and comparison with healthy controls. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Pinto-Bastos, A.; Arrojado, F.; Brandão, I.; Machado, P.P. Stability of problematic eating behaviors and weight loss trajectories after bariatric surgery: A longitudinal observational study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meany, G.; Conceição, E.; Mitchell, J.E. Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: Effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Wadden, T.A.; Ashare, R.; Spitzer, J.C.; McCuen-Wurst, C.; LaGrotte, C.; Williams, N.; Soans, R.; Tewksbury, C.; Wu, J.; et al. Psychopathology, disordered eating, and impulsivity as predictors of weight loss 24 months after metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Hreins, E.; Foldi, C.J.; Oldfield, B.J.; Stefanidis, A.; Sumithran, P.; Brown, R.M. Gut-brain mechanisms underlying changes in disordered eating behaviour after bariatric surgery: A review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitznagel, M.B.; Garcia, S.; Miller, L.A.; Strain, G.; Devlin, M.; Wing, R.; Cohen, R.; Paul, R.; Crosby, R.; Mitchell, J.E.; et al. Cognitive function predicts weight loss after bariatric surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013, 9, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.; Camacho, M.; Fernandes, A.B.; Cotovio, G.; Torres, S.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J. Reward-related gustatory and psychometric predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: A multicenter cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 751–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, S.; Mirghani, H.; Alhazmi, K.; Alatawi, A.M.; Brnawi, H.; Alrasheed, T.; Badoghaish, W. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy effects on obesity comorbidities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 953804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabosky, J.; Masheb, R.; White, M.; Rothschild, B.; Burke-Martindale, C.; Grilo, C. A prospective study of body dissatisfaction and concerns in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 6- and 12-month postoperative outcomes. Obes. Surg. 2006, 16, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SG | RYGB | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.6 ± 15.4 | 32.4 ± 7.9 | 0.142 |

| Females, % | 55.6 | 70.0 | 0.041 * |

| Married, % | 60.5 | 55.7 | 0.524 |

| Presence of chronic disease, % | 24.3 | 28.6 | 0.218 |

| Insulin resistance, % | 14.9 | 17.1 | 0.150 |

| Cardiovascular diseases, % | 10.8 | 15.7 | 0.056 |

| Arthritis diseases, % | 6.8 | 8.6 | 0.110 |

| Physical activity level | 1.48 ± 0.4 | 1.43 ± 0.2 | 0.250 |

| Body weight at T0, kg | 110.1 ± 12.5 | 106.3 ± 20.3 | 0.096 |

| Body weight at T1, kg | 85.2 ± 11.2 | 80.7 ± 14.1 | 0.082 |

| Mean weight loss, % | 22.6 ± 6.1 | 24.1 ± 5.4 | 0.125 |

| BMI at T0, kg/m2 | 42.1 ± 4.0 | 41.4 ± 4.5 | 0.351 |

| BMI at T1, kg/m2 | 32.0 ± 4.1 | 29.8 ± 4.2 | 0.145 |

| Presence of PEBs ¥ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0, n (%) | T1, n (%) | |||||

| EDE-Q | SG | RYGB | p | SG | RYGB | p |

| Restraint | 15 (20.3%) | 18 (25.7%) | 0.160 | 11 (14.9%) | 13 (18.6%) | 0.098 |

| Eating concern | 9 (12.2%) | 13 (18.6%) | 0.096 | 3 (4.1%) | 8 (11.4%) | 0.040 * |

| Shape concern | 52 (70.3%) | 54 (80.0%) | 0.240 | 10 (13.5%) | 16 (22.3%) | 0.021 * |

| Weight concern | 59 (79.7%) | 60 (85.7%) | 0.110 | 8 (10.8%) | 15 (21.4%) | 0.010 * |

| Total | 42 (56.8%) | 45 (64.3%) | 0.168 | 4 (5.4%) | 12 (17.1%) | 0.012 * |

| The Percentage of Total Weight Loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | RYGB | |||

| r | p | r | p | |

| PFS total | 0.163 | 0.014 * | 0.146 | 0.120 |

| Food available | 0.255 | 0.040 * | 0.186 | 0.024 * |

| Food present | 0.126 | 0.020 * | 0.205 | 0.046 * |

| Food tasted | 0.086 | 0.095 | 0.195 | 0.110 |

| EDE-Q total | 0.124 | 0.010 * | 0.122 | 0.010 * |

| Restraint | 0.025 | 0.424 | 0.179 | 0.138 |

| Eating concern | 0.140 | 0.254 | 0.088 | 0.470 |

| Shape concern | 0.167 | 0.042 * | 0.057 | 0.637 |

| Weight concern | 0.094 | 0.037 * | 0.022 | 0.854 |

| Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | RYGB | |||

| β | p | β | p | |

| PFS Total | 0.092 | 0.382 | 0.102 | 0.287 |

| PFS—FA | 0.045 | 0.552 | 0.053 | 0.472 |

| PFS—FP | 0.051 | 0.438 | 0.074 | 0.302 |

| PFS—FT | 0.060 | 0.368 | 0.086 | 0.297 |

| EDE-Q Total | 0.067 | 0.417 | 0.079 | 0.270 |

| EDE-Q—R | 0.056 | 0.452 | 0.063 | 0.365 |

| EDE-Q—EC | 0.044 | 0.540 | 0.061 | 0.374 |

| EDE-Q—SC | 0.075 | 0.431 | 0.097 | 0.276 |

| EDE-Q—WC | 0.069 | 0.465 | 0.082 | 0.290 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yilmaz, C.S.; Turker, P.F. Changes in Hedonic Hunger and Problematic Eating Behaviors Following Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Study of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy. Healthcare 2026, 14, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010127

Yilmaz CS, Turker PF. Changes in Hedonic Hunger and Problematic Eating Behaviors Following Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Study of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010127

Chicago/Turabian StyleYilmaz, Can Selim, and Perim Fatma Turker. 2026. "Changes in Hedonic Hunger and Problematic Eating Behaviors Following Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Study of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010127

APA StyleYilmaz, C. S., & Turker, P. F. (2026). Changes in Hedonic Hunger and Problematic Eating Behaviors Following Bariatric Surgery: A Comparative Study of Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Versus Sleeve Gastrectomy. Healthcare, 14(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010127