Abstract

The relationship between university performance and performance-based funding models has been a topic of debate for decades. Promoting performance-based funding models can create incentives for improving the educational and research effectiveness of universities, and consequently providing them with a competitive advantage over its competitors. Therefore, this paper studies how to measure the performance of a university through a mathematical multicriteria analysis and tries to link these results with certain university funding policies existing in the Spanish case. To this end, a reference point-based technique is used, which allows the consideration and aggregation of all the aspects regarded as relevant to assess university performance. The simple and easy way in which the information is provided by this technique makes it valuable for decision makers because of considering two aggregation scenarios: the fully compensatory scenario provides an idea of the overall performance, while the non-compensatory one detects possible improvement areas. This study is carried out in two stages. First, the main results of applying the proposed methodology to the performance analysis evolution of the largest three Spanish public university, over a period of five academic years, are described. Second, a discussion is carried out about some interesting features of the analysis proposed at regional level, and some policy messages are provided. The “intra” regions university performance analysis reveals some institutions with noteworthy behaviors, some with sustained trends throughout the analyzed period and other institutions with more erratic behaviors, within the same regional public university system despite having the identical funding model. However, the findings “inter” regions also reveal that only Catalonia has developed a true performance-based model, in theory and in practice, which has contributed to achieving excellent results at regional level in both teaching and research.

1. Introduction

Public universities around the world carry out their activities nowadays in a highly competitive context. The proliferation of rankings at national and international levels is a clear sign of the global nature of the Higher Education market. Consequently, political and academic authorities are increasingly concerned with improving the performance of universities in public systems. The general structure of income and expenses of European public universities makes them highly dependent on the financing policies applied by governments [1,2].

The Spanish public university system is characterized by being very homogeneous, having many universities with a medium-high quality (upper intermediate) in terms of teaching and research, and for not occupying prominent positions in the global rankings. Only the University of Barcelona has managed to position itself above the Top-200 of the Shanghai ranking. As for the functional dependence of Spanish universities, there is a double circumstance. On the one hand, the master lines of higher education and actions related to R&D are a state policy and therefore, fall under the responsibility of the central government. On the other hand, Spain is one of the European countries where there is a higher level of decentralization in university policy. After centuries of centralization and uniformity, in 1996 the process of decentralization of higher education was completed. Therefore, from that moment on, regional governments make the decisions that most directly affect the financial resources of the universities [3]. In this sense, the Spanish public university system is similar to that of Germany, which is the other large country in the European Union that has a similar level of decentralization in higher education. For this reason, Spanish public universities constitute an excellent test bed to check the impact of different financing policies on their performance.

Therefore, the fundamental question arises of how to measure the performance of a university [4]. In general, public universities carry out tasks of a diverse nature, which can be encompassed in the teaching and research missions, leaving apart the so-called third mission [5]. Nevertheless, even this classification is an over-simplification, since university performance is a multidimensional reality, which requires suitable tools for its measurement. Lately, the rise of the information society has brought with it the use of an increasing amount of data in all areas. University systems are no exception and those responsible for Spanish public universities (the CRUE, rectors’ conference) manage a database that contains multiple teaching and research indicators. However, this large amount of information can be hard to manage, and it is difficult to draw conclusions about the overall performance of each university from it. For this reason, it is frequently necessary to build composite indicators that synthesize all this information, so that they are useful tools in decision making processes both at institutional level and at system level.

Given this multidimensional nature of university activity, mathematical multi-criteria decision-making tools are especially suitable for the construction of composite indicators in this area. There are various multi-criteria techniques developed for this purpose. In any case, two critical details must be considered. On the one hand, it is important to allow decision-making centers to establish the levels they consider admissible and/or desirable for the given indicators, in order to measure the performance of the universities based on the achievement of these levels. On the other hand, the construction of composite indicators always entails a certain loss of information. It is vital that this process does not prevent decision-making centers from detecting the weak points of the different universities and, therefore, their priority areas for improvement.

For all the above reasons, this work studies the evolution of the performance of the universities of three Spanish regions that have been chosen following two criteria. First, they comprise more than 50% of the Spanish university activity and second, they have had essentially different financing models. This allows us to analyze the impact of these different financing policies on this performance evolution. To carry out this measurement, the MRP-WSCI (Multiple Reference Point Weak and Strong Composite Indicators) multi-criteria technique to construct composite indicators is used. This technique allows the use of the previously mentioned reference levels and also provides two composite indicators. The weak indicator constitutes an aggregate measure of the performance of each university, while the strong indicator works as a red flag showing its weak points.

The study is carried out dynamically, in a time horizon that allows us to contemplate the evolution of the universities studied for a period of five academic years (from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017). The analysis covers this period especially for three reasons: first, as a result of the global economic and financial crisis, the Spanish Government implemented the Public Expenditure Rationalization Law in 2012 [6], where structural changes were made within the Spanish educational scope; second, the study is carried out a decade after the implementation of the performance-based funding models (these funding models entered into force as from 2006–2007); and third, all the performance-based funding models that were still in force were stopped in 2017. More precisely, the study comprises two phases. First, the evolution of the performance of each of the universities of each region is examined. Second, the general performance evolution of each regional system selected will be analysed.

The reminder of this paper is organized as follows: A literature review is performed in Section 2. Section 3 gives an overview of the institutional context and the data used. The MRP-WSCI approach is developed in Section 4. The empirical results are presented in Section 5. In Section 6, a discussion about some interesting features of the analysis proposed, and some policy messages are provided. Finally, Section 7 presents some conclusions. Moreover, for completeness, some elements of the MRP-WSCI method are described in Appendix A, and the main results are given in Appendix B and Appendix C.

2. Literature Review

The role that higher education institutions have to play in the transformation toward a more competitive society in terms of social, economic and cultural developments is attested to in both the scholar and practitioner literature [7,8,9,10,11,12]. According to [13], performance management in universities has been an important research topic and has received great attention from researchers. In this sense, universities are increasingly being asked to demonstrate to their community the benefit they provide in the knowledge economy. This means that higher education institutions need to develop missions to ensure that accumulated knowledge is circulated directly back to society and that they do not become “ivory towers” [14].

The performance measurement and evaluation of higher education systems has been implemented from differing perspectives and with differing methodologies. According to [15], the assessment of a university performance is inherently multi-faceted, and therefore, several indicators have to be taken into consideration, covering quality and results issues for all the missions carried on within a university system.

According to [16], the usefulness of teaching and research indicators will also be affected if evolving funding mechanisms give an increasing role to market forces, for instance in the British Higher Education System. In fact, literature about performance-based funding and performance agreements has focused on teaching, research and other indicators to improve the accountability, diversity and the attention for efficiency in higher education [17,18].

With the paradigm shift from New Public Management to New Public Governance at the beginning of this century, most countries’ higher education systems have established university funding models that are based on quantitative indicators to allocate public resources [19,20]. However, these are unsophisticated models that imply the selection of indicators that are less useful for the decision-making process, which is very complex in the case of research-intensive universities.

Global rankings methodologies have tried to catch the performance of higher education institutions of all over the world in a simple manner, offering ordinal or numerical results, which are difficult to interpret. Specifically, some initiatives with commercial interests, such as ARWU, QS, Times, CWTS, etc., …, compare higher education institutions through league tables using simple aggregation techniques. This implies a compensatory nature among indicators, and the impossibility of detecting inter-universities differences according to their performance in all the criteria, which is what policymakers need. Consequently, university rankings provide limited information and loose the multi-dimensional aspects of higher education activities. In general, one-dimensional classifications reduce the institutional heterogeneity to a single source of diversity, and therefore, they do not identify comparable institutions [21].

In contrast, multidimensional rankings emerged allowing for a better characterisation of the institutional differentiation. A well-known multidimensional classification is the initiative drove by the European Commission with U-Multirank, a tool that also allows producing customized rankings [22]. According to [23], these multidimensional rankings correspond to ex-ante classifications, meaning that they do not provide a theoretical framework for the interpretation of the information and for the selection of a group of universities to be either benchmarked or ranked. Similar experiences to that of U-Multirank are the Ranking CyD and the U-Ranking (BBVA-IVIE) of Spanish universities.

Anyway, notwithstanding their limitations and the numerous criticisms received, the success of the well-known global universities rankings shows that universities are presently immersed “in an age of measurements and comparisons” [10], which according to [24], has resulted in rankings balanced from “a consumer product” to “a global strategic instrument”. Therefore, the use of rankings must be given a fair value, whether they are one-dimensional or multidimensional, as public policy decision-making tools at the government and institution-level. In the view of the authors, it can be very troubled to use the results of global rankings, especially commercial ones, to make higher education policy decisions and to develop new funding models adapted to the size of the university systems (in terms of financial resources) and their level of specialization in research and teaching.

Regarding the scientific literature, most of the papers published have used a system of individual indicators, measuring all the different aspects of a university system, and aggregated them in an overall composite measure [12,25,26,27,28,29]. Obviously, the consideration and measurement of all the indicators separately provide a complete overall picture without any loss of information. However, the consideration and use of a so-called composite indicator has become a necessary stage in the assessment of such multidimensional and complex concepts.

In addition, the recognition of the specific multidimensional nature and complexity of a university system highlights the crucial need for using methodologies that are capable of managing this nature, while causing the least possible loss of information, i.e., assessing university performance systems (and making comparisons between them) makes it necessary to use composite indicators, but, the information provided by these composite indicators should be as maximal as possible [30].

The issue of constructing an overall composite measure has been regarded by several authors as a multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) problem [31,32,33,34]. Specifically, according to [35], in higher education, MCDM methods are adjusted perfectly to planning and evaluating complex projects and are used to design public policies when it is necessary to obtain a comprehensive assessment from multiple criteria and a high number of stakeholders.

According to [34], depending on the MCDM aggregation method used, the compensatory character among the individual indicators can be full (e.g., the Simple Additive Weighting, the Utility Theory Additive, the Simple Multi-Attribute Rating Technique, the Data Envelopment Analysis and the Technique for Order Preferences by Similarity to Ideal Solutions), partial (e.g., the Multi-Utility Theory, the Multi-Attribute Theory and the Weighted Product) or zero (e.g., the Elimination and Choice Expressing Reality and the Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations).

Moreover, within the family of MCDM aggregating methods, some techniques allow for different compensation degrees, depending on the aggregation scenario chosen. On the one hand, Ref. [36] based on [37,38], obtain a fully compensatory (the Net Goal Programming) composite indicator and a non-compensatory (the Restrictive Goal Programming) composite indicator. To this end, a reference (aspiration) level is established. On the other hand, Ref. [39], making use of a set of reference levels, construct different composite indicators allowing for different compensatory scenarios (the Multiple Reference Point-based Weak and Strong Composite Indicators). First, the weak indicator (WCI) has properties of classical weighted means and it allows for a full compensation. Second, the strong indicator (SCI) measures the worst performance of the unit without allowing for any compensation. Both compensatory and non-compensatory scenarios are designed in order to be jointly considered. This way, a valuable and complementary information about the performance of the units is put in the hands of policymakers. Finally, Ref. [40] develop the Multiple Reference Point Partially Compensatory Indicator (MRP-PCI), where a different compensation index can be established for each indicator. It should be noted that the fully and non-compensatory composite indicators provided by the MRP-WSCI are particular cases of the MRP-PCI approach. These MRP-WSCI and MRP-PCI find their origins in [41,42,43].

Therefore, the novelty of this paper consists of linking composite indicators of university performance with performance-based university funding models. The consideration of the MRP-WSCI approach for the assessment of each university individually and for the region globally generates useful insights to understand the mechanisms driving the performance of teaching and research (and their impacts or consequences) at institutional level and at regional level.

3. Background

This section provides the context of the information that will be discussed in the paper. On the one hand, the Spanish institutional context is described. On the other hand, the system of indicators considered is presented.

3.1. Institutional Context

The Spanish university system comprises 82 universities, out of which 50 are public, and the rest are private. All of them are distributed throughout the 17 Spanish regions. The introduction of the Organic Law “LOMLOU” (https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2007/04/12/4 (accessed on 16 June 2021)) by the National Government and “the Modernization Agenda for Universities” introduced by the European Union [44] have been important added values for the Spanish universities. As a result, Spanish universities have been forced to redefine themselves to adapt to the new requirements of the European Higher Education Area.

According to [45], teaching and research are core tasks (main missions) of any higher education system. On the one hand, the Spanish scientific publications have significantly raised from 2000. Regarding the world share of top 10% highly cited scientific publications, according to [46], Spain’s share has increased in almost 0.9% from 2000 to 2016. Furthermore, Spain has increased its international scientific co-publications by 16% over the period 2000–2011 [47]. On the other hand, Spanish official university programs are listed by the Ministry of Education and structured into three different degree levels: Grade degrees, University Master degrees and Doctoral degrees. Moreover, the Spanish university system has experienced a huge increase in the number of bilingual programs and in the international student mobility. According to [48], within the university training programs, the subjects taught in a language other than Spanish have grown by more than 50% in recent years, while the net balance of Erasmus students has increased by 248.03% from 2012–2013 to 2017–2018.

To develop their functions, the Spanish public universities are formed by university schools, faculties, departments, university institutes for research, doctoral colleges and by other necessary schools or structures. Overall, the Spanish public university system is relatively homogeneous at institutional level and quite complex at regional level, which includes different regulations and levels that are interconnected to each other.

Concerning higher education policies, Spain is considered among the highest decentralized systems in Europe. The Regional Governments are important decision-making authorities in university matters. On the one hand, they have competencies for the creation, modification and elimination of university programs and they set the tuition fees of the universities in their territories. In the last decade, Catalonia and Madrid have chosen to increase tuition fees by more than 66% since 2012, welcoming a change in state regulations for the establishment of tuition fees. Meanwhile, Andalusia has maintained its tuition fees stable throughout the whole period analyzed, being one of the lowest in Spain. On the other hand, regional funds are core funding of public universities, which represent over 70% on average of university budget, as responsibility for university finance depends on the regions.

At regional level, three Spanish regions are particularly noteworthy in terms of Higher Education Systems and different financing Higher Education policies:

- The Andalusian university system has 1 private and 10 public universities (one of them being distance-learning). The Andalusian Public University System has historical and traditional universities, which are larger, in general (such as the Universities of Granada and Seville) and very modern universities that are smaller (such as the Universities of Almería, Huelva and Jaén). It is the largest Spanish university system by number of faculty members and researchers, and it has more than 230,000 students.The Andalusian region has been one of the pioneers in Spain in introducing some performance mechanisms to articulate a university funding model that rewards for better performance and quality of teaching and research. In this way, the first model for the Andalusian public universities (2002–2006), signed in November 2001, constitutes a first attempt to establish a mix cost-oriented and performance-oriented funding formula, to allocate around 7.5% of the university budget linking to outputs. The subsequent university funding models correlate regional funds with (quantitative) measures of institutions’ past activity (10%), in addition to basic financing that is based primarily on costs (approximately 90% of the regional support). The small amount of public resources that are distributed with a performance criteria causes that, conform to reality, the funding system has remained as a formula funding model based on provider (supplier) in Andalusia in the analyzed period (2012–2017). Please note that this funding model is not maintained from 2017.Furthermore, the Andalusian universities are increasingly depending on public funding from the Regional Government, which leads to a greater equalization among them in terms of financial effort per student. This is reflected in a more similar pattern in terms of teaching and research results funding (“intra” universities), although there are different research performance behaviours as shown, for instance, in ARWU (Academic Ranking of World University) and [12].As a result of the landscape of research in Andalusia, the regional government launched in 2015 an international talent recruitment program, called TALENTIA, so that Andalusian universities could attract and bring back highly regarded research professors, although it has resulted in few professors and highly cited researchers received by universities, because of the scarce resources available for the program.

- The Catalan university system is also one of the largest in Spain, with approximately 200,000 students. It comprises 12 universities, seven of which are public research universities. The Catalan public university system offers a certain differentiation or institutional profiling: first, several universities with prominent positions in the international rankings regarding research, such as the University of Barcelona, the Pompeu Fabra University or the Autonomous University of Barcelona; second, universities that are able to attract industry income, such as the Universitat Politecnica de Catalonia and Rovira i Virgili; and third, several peripherical and smaller universities with excellence levels in teaching activities, such as Universities of Girona and Lleida.The Catalan university funding model based on a formula base began in 2002. It is a funding model based on inputs (cost-oriented), but with a clear performance-oriented intention (the output weight is around 40%). The financing mechanism consists of four different grants: fixed, basic, derivative, and strategic subsidies. In the funding model implemented in 2006, the strategic subsidy integrated the contract agreements that the Catalan government had been establishing with universities in the old periods (a supplementary funding program was created with the UPC in 1997). In addition, in 2008, a target funding program was created, complementary to the model, which represents just over 5% of the total funding that universities received.Moreover, Catalonia Region has promoted the excellence in research activities through CERCAS (Catalan Centers for Research) but also through initiatives such as ICREA (Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies) that attract and retain talent all over the world. ICREA research professors choose their host institutions within the Catalan research system, some of which are universities, and act as research leaders and attractors of additional talent. This initiative has influenced the high levels of research in many Catalan universities because it has generated synergies.

- The Madrid university system is the largest one in Spain by number of students and the second in number of faculty members and researchers. It comprises six on-site public universities, which offer formation to approximately 220,000 students, and eight private universities that train approximately another 100,000 students. Due to the variety of academic programs and the R&D possibilities that the region offers, the Madrid university system attracts students and researchers from all over Spain and other countries.Moreover, it is worth examining the Madrid university system, since it has not followed a performance-based funding. However, an attempt was made in 2006 with the introduction of new policy instruments in the performance agreement 2006–2010, to achieve specific types of results, but its implementation was quickly truncated by the immediate economic crisis of 2008. It can be stated that there is no funding model anytime in Madrid region and, therefore, an annual negotiation together with an incremental distribution model, maintains financial dependency from regional funds, although universities set their own strategies in terms of teaching and research. Specifically, in the absence of a funding model, the resource-sharing system has been discretionary and based on political decisions with bilateral negotiations between the regional government and the six public universities in Madrid. This fact leads to many differences among the six universities within Madrid region.Furthermore, the Madrid university system is characterized by: (i) being one of the systems with a greater basic and applied research, given the prominent position of some Madrid universities, such as the Autonomous University of Madrid and the Complutense University; (ii) its ability to raise private funds, especially by the Polytechnic University of Madrid; (iii) and its joint research with the IMDEA Institutes (Research centres of excellence based in the Region of Madrid: https://www.imdea.org/en/ (accessed on 16 June 2021)) and the Mixed Centers of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) (https://www.csic.es/en (accessed on 16 June 2021)) that work jointly with researchers from the six Madrid public universities.

Considering the previously mentioned comments, the Andalusian, Catalan and Madrid university systems have been considered in this analysis, given the differences in their funding models over time. First, while the finances of the three systems rely primarily on public resources, they diverge in the amount of private income from families (Catalonia and Madrid have increased their tuition fees against Andalusia, that maintains very low levels and without distinction by subject-mix). Second, Andalusia has refunds of tuition fees conditional on academic performance of students. Third, they have different university policies to boost research (more accentuated in the cases of Catalonia and Madrid, with the creation of their own Research Centers such as ICREA & IMDEA), and they comprise most of the flagships of the Spanish university system according to international rankings.

3.2. System of Indicators for the Spanish Public University System

The data used in this paper were mainly collected from two sources: the report by the Spanish University Rectors’ Conference (CRUE) (https://www.crue.org/listado-publicaciones/ (accessed on 16 June 2021)), and the results of the Spanish University System by the Research Institute for Spanish Higher Education (IUNE Observatory) (http://www.iune.es (accessed on 16 June 2021)).

Given the growing relevance of teaching and research performance for any university system, both missions (or core tasks) have been separately considered in the analysis. Therefore, the system of indicators is structured as follows:

- Teaching: in order to measure the teaching mission of the universities, the quantity and quality of the results obtained and the international projection of the teaching activities are taken into account. Therefore, two sub-blocks have been considered:

- The teaching Results are measured using the indicators available about the students’ performance. They measure how many students submit to evaluation, how many pass their courses, how many graduate and how many drop out. Additionally, the number of post-graduate students has been considered.

- The External projection is linked to the bilingual official masters degrees, the percentage of foreign students and the percentage of students in exchange programs.

- Research: this mission includes the resources available for research, and the corresponding outputs, in terms of their quantity and quality. Namely, the following sub-blocks have been considered:

- Given their importance in all the rankings, the Publications have been considered separately from the rest of the research activity. The amount of publications per doctor, and the quality of the publications (in terms of the relative position of the journals and the citations) have been included.

- The Other research activities consider the international collaborations, the number of doctoral theses defended, the participation in projects and the overall official recognition of research, provided by the National Agency of Evaluation.

- Finally, the Projects approved for research, taking into account the research grants and contracts and the success rate in National and European research projects have been considered.

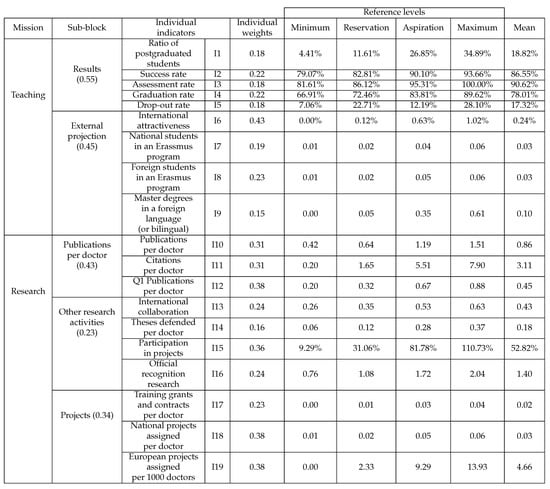

Summing up, a set of 19 performance indicators has been considered, taking into account both their relevance to measure the teaching and research performance of the Spanish public universities and their availability (Figure A1 in Appendix A.1 shows the individual indicators and their corresponding sub-blocks). The set of indicators considered is frequently used by several Spanish institutions (e.g., the U-Ranking project of the BBVA Foundation and the IVIE (https://www.u-ranking.es/index2.php (accessed on 16 June 2021)) and the CyD Ranking (http://www.rankingcyd.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2021)). Anyway, it must be pointed out that the indicators considered in the analysis are the ones provided and used by the Spanish organizations responsible for collecting information about the Spanish universities and analyzing their performance. Therefore, the use of this system of indicators does not imply any consideration on the part of the authors about its suitability to measure the teaching and research performance of universities. However, the methodological proposal of this research can be easily adapted to use other indicators, should they become available

4. Methodology

To analyze the evolution of the Andalusian, Catalan and Madrid public universities performance, the Multiple reference point-based weak and strong composite indicators (MRP-WSCI; [39]) is used. This methodology allows us to build compensatory and non-compensatory composite indicators, where any number of reference levels can be used. The MRP-WSCI method is a generalization of the double reference method [43]. The reference point method was originally proposed by [41], and was initially designed to solve multi-objective programming problems, by generating efficient solutions that were closer to certain (desired) reference levels for the objectives set. Later on, Ref. [42] extended this methodology to a double reference point scheme, suggesting its use for the construction of objective rankings, where a reservation level (minimum level regarded as admissible) and an aspiration level (level regarded as desirable) can be specified for each objective. Refs. [43,49] adapted and further developed this idea for the construction of composite indicators, according to the degree of compensation between the indicators and based on the weights given by the user.

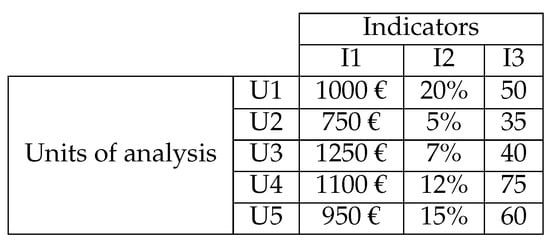

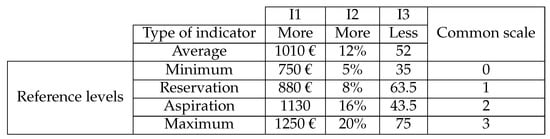

In this paper, in order to construct the MRP-WSCI composite indicators, the following aspects have been considered:

- Reference levels: For each indicator i, four reference levels (minimum, ; reservation, ; aspiration, ; and maximum, ) are established. Please note that is a level regarded as acceptable, i.e., values worse than the reservation level are regarded as poor performance values, and is a level regarded as desirable, i.e., values better than the aspiration level are regarded as good or desirable.According to [39], these reference levels can be relative (statically set) or absolute (given by a decision maker). In this paper, the four reference levels have been statistically established, considering data of all the Spanish public universities for the entire period analyzed (from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017). Namely, when the indicator is of type “the more, the better”, the has been set as the average value between the mean () and the of each indicator for all Spanish public universities for the entire period. On the other hand, the is the average value of () and the (for further details about the reference levels of each indicator, see Figure A1 in Appendix A.1). These reference levels have two consequences in the process. First, the relative position of each university is analyzed with respect to the whole Spanish public university system. Second, since the reference levels are fixed for the entire period analyzed, any university improvement or worsening relates only to its own performance.Please note that an outlier detection, through the interquartile range () method, is carried out [50]. According to this test, two different outliers can be detected: mild outliers (; ) and extreme outliers (; ). In this case, no extreme outliers were detected, while the mild outliers are assigned, for the corresponding achievement function, the minimum or maximum value (depending on its relative position) of the scale.

- Achievement functions: The purpose of calculating the achievement functions () is twofold. First, they allow the normalization of the indicators, i.e., all the indicators are brought to a common measurement scale. Second, they inform about the relative position of each university with respect to the reference levels given (see more details about the construction of the achievement function, , in Appendix A.2).Specifically, in this paper, all the indicators are translated to a common scale from 0 to 3. This way, for each indicator i, different performance levels are defined (See Figure 1):

Figure 1. Definition of the three performance levels.

Figure 1. Definition of the three performance levels.- Poor ⇒ The university performs worse than the corresponding (values between 0 and 1).

- Fair ⇒ The university performs better than the level, but worse than the level (values between 1 and 2).

- Good ⇒ The university performs better than the corresponding (values between 2 and 3).

- Aggregation: A particular feature of the MRP-WSCI method is the possibility of constructing two different composite indicators, by considering the compensation degree among the indicators. In this paper, in order to analyze the universities overall performance, the Weak Composite Indicator (WCI) is used, which allows for full compensation. Moreover, the possible improvement areas of each university will be detected through the Strong Composite Indicator (SCI), which does not allow for any compensation. In particular, as can be observed in Figure 2, the WCI and SCI are provided for each sub-block and each university mission through two aggregation steps, i.e., in the first step the individual indicators are aggregated in order to construct the WCI and SCI by sub-block; and, in the second step, the corresponding sub-blocks are aggregated in order to obtain the WCI and SCI by mission. Therefore, the WCI by sub-block (and mission) gives an idea about the overall performance of each university within the corresponding sub-block (and mission), while the SCI measures the worst performance of each university within the corresponding sub-block (and mission). Specifically, the SCI provides a measure of the worst individual indicator (and sub-block) of each university, and therefore, it gives an idea about the improvement areas. The details about the construction of the MRP-WSCI are displayed in Appendix A.3.

Figure 2. Steps for constructing the WCI and SCI by universities for each academic year.

Figure 2. Steps for constructing the WCI and SCI by universities for each academic year.

Of course, the indicators and sub-blocks used to measure university performance have different relative importance. This aspect has been considered when constructing the MRP-WSCI composite indicators. To this end, a group of experts in the field of the Spanish universities, integrated by researchers and professionals from different fields of research and different Spanish public universities, has assessed the weights of the individual indicators and sub-blocks. For further details about the weights assigned to each indicator and sub-block, see Appendix A.1.

5. Results

This section describes the main results of applying the MRP-WSCI to the performance analysis evolution of the three Spanish public university systems considered. To this end, although the analysis has been made for each of the five academic years considered, due to space limitations, the results of the initial and final year’s performance of each university within the chosen regions are discussed in detail for the teaching and the research missions, while the results for all the academic years are displayed in Appendix B.

Please note that in order to set the reference levels, data of all the Spanish public university system have been considered. Therefore, the analysis carried out measures the position of the selected universities in the Spanish global context.

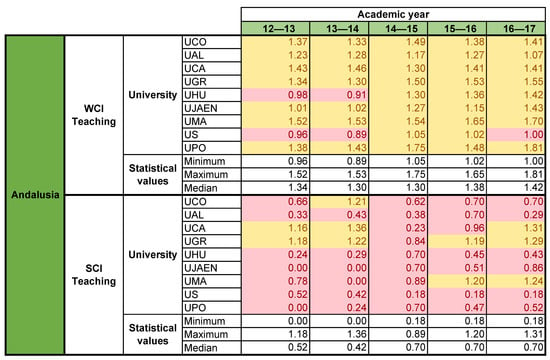

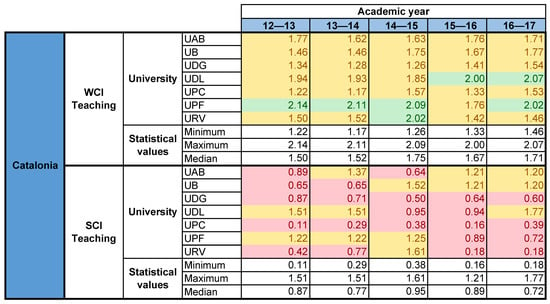

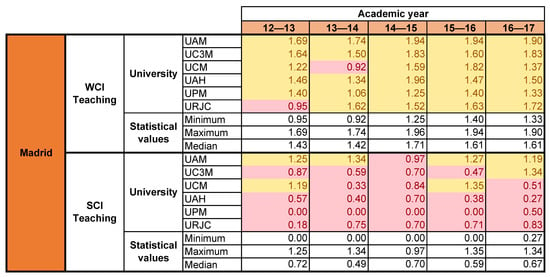

5.1. Teaching Mission

Next, the teaching performance evolution of the Andalusian, Catalan and Madrid public universities by considering their compensatory and non-compensatory composite indicators is described. To this end, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the results of the teaching WCI and SCI for the first, 2012–2013, and the last, 2016–2017, academic years considered.

Figure 3.

Evolution in the teaching mission of the Andalusian public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

Figure 4.

Evolution in the teaching mission of the Catalan public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

Figure 5.

Evolution in the teaching mission of the Madrid public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

In general, it can be noticed that, except for six universities (the UAL and the UCA in Andalusia, the UAB, the UPF and the URV in Catalonia, and the UPM in Madrid), the 2016–2017 WCI (fully compensatory) scores for all the universities are better than those of 2012–2013, i.e., comparing the initial and final year’s performance, it can be assumed that the teaching performance of the Andalusian, Catalan and Madrid universities has improved overall. In particular, the universities that have experimented a greatest improvement are the URJC from Madrid (+0.77), the UHU from Andalusia (+0.44) and the UPC from Catalonia (+0.31). However, all universities have still room for improvement, since most of them are located in the “fair” performance level (WCI scores between 1 and 2, which means that, overall, they perform better than the reservation level, but worse the corresponding aspiration level).

On the one hand, the teaching WCIs of the Andalusian public university system vary in the range [0.96, 1.52] in the initial situation and goes to [1.00, 1.81] in the final situation. It is the one with the lowest range of variability at the beginning, but the highest one at the end. On the other hand, the starting points for the Catalan universities are in the range [1.22, 2.14], which is the best situati on compared to the other university systems, and they remain the leaders in the final period, [1.46, 2.07]. Finally, the Madrid system has the second highest range of variability between universities in the first year. The teaching WCIs of the Madrid universities are in the range [0.95, 1.69] in 2012–2013, but this range is reduced in the last period, [1.33, 1.90], being the one that most reduces the range of variability between universities in the last period.

Regarding the SCI (non-compensatory) values, only 4 universities manage to perform better than the reservation level for both SCI values (UCA and UGR in Andalusia, UDL in Catalonia and UAM in Madrid). Moreover, the universities that have achieved the best improvements in the strong indicator (that is, those that have improved their main poor performance value most) are the UJAEN from Andalusia (+0.86), the URJC from Madrid (+0.65), and the UB from Catalonia (+0.55). In this case, the Andalusian universities vary in the range [0.00, 1.18] in the initial situation, and it increases in the final period, [0.18, 1.31]. The Catalan system, as for the WCI, is the one with the best starting values and the highest initial variability, [0.11, 1.51]. This variability, unlike the other two university systems is greater in the final period, [0.18, 1.77]. Specifically, the Catalan system presents the greatest range of variability among its universities in the SCI values for both academic years. It should be noted that, for both courses, the best values for the Catalan university system are better than the best values for the other two systems (SCI of the UDL = 1.51 and 1.77, respectively), i.e., the worst performance of Catalonia for the teaching mission is better, in the final situation, than those of the Andalusian and Catalan systems. Finally, the range of variation between the Madrid universities is [0.00, 1.25] in the initial period, while in the final period is reduced, [0.27, 1.34].

Let us now examine the universities of each region in further detail. Within the Andalusian universities, it is noteworthy the UPO, which has the best WCI in 2016–2017 and which has experienced a significant improvement of 0.43 points. Specifically, within the Andalusian university system, it has the second best improvement in the two teaching sub-blocks (Results, +0.48 and External projection, +0.37). At the indicator level, the UPO has improved in six of the eight teaching indicators, with a very significant improvement in the Success (+1.97) rate, which was located in the poor performance level at the initial period. It should be noted that, although the UPO has not managed to significantly improve a poor performance value, International attractiveness, its SCI has also experienced a notable improvement (+0.52). This occurs because the UPO had the worst possible value (0.00), in year 2012–2013, in the highest weighted indicator within the most important teaching sub-block (Success rate, Results). On the other hand, the UGR has the highest SCI value for the initial period and the second best SCI values for the final period. Specifically, jointly with UAL, they are the only Andalusian universities whose SCIs are higher than 1 for both courses. This means that the UGR and the UAL have absolutely all their teaching indicators above the reservation level at the two academic years. The UMA is the only Andalusian university whose SCI value has changed from the “poor” to the “fair” performance level (0.78 in 2012–2013 and 1.24 in 2016–2017). This is because its only poor performance value in the initial period was in the Ratio of post-graduated students indicator, which has experienced an improvement of +0.44, being in the fair performance level at the final period. Additionally, it is noteworthy the case of UJAEN, which presents one of the best improvements in the Andalusia system for the WCI (+0.42) and the best improvement for the SCI (+0.86), being close to 1 in the last period. Specifically, the UJAEN has improved seven of the eight teaching indicators from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017. Regarding its poor performance values, out of the three it had initially, it maintains only one at the final situation, which is International attractiveness (significantly improved, but still below the reservation level). In general, most of the poor performance values for the Andalusian universities in the final year are in this indicator: International attractiveness (poor performance for five of the nine universities). Furthermore, it should be noted that two Andalusian universities have worsened their SCI from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017, which means that paying special attention to its poor performance values remains an overarching goal for the Andalusian university system.

Regarding the Catalan system, all the public universities perform better than the reservation level for both WCI. The cases of UDL and UPF are noteworthy. The WCI value of the former is above the aspiration level in the last period (2.07). Nevertheless, even being in the “good” performance level for both years, it can be observed that the WCI value of the UPF has slightly worsened (2.14 and 2.02, respectively). This is because the UPF has slightly improved in only two indicators, while it has worsened in three indicators, even reaching a poor performance in International attractiveness (this indicator worsens in 0.39). In the rest of the teaching indicators, the UPF has the best possible performance (3.00) in the two years analyzed. On the other hand, the UDL has improved its WCI by 0.14 points and its SCI by 0.27 points in the period studied. Specifically, the UDL is the only Catalan university with both SCI values greater than 1. This is because the UDL, which was already performing better than the reservation level for all the teaching indicators, has improved in seven of the eight indicators considered (only the Foreign students in an Erasmus program indicator has experienced a decrease, −0.23). On the other hand, the SCI of the UPF has worsened (−0.50). In this case, the International attractiveness indicator, which was very close to the reservation level (1.04) in the initial course, has significantly worsened (−0.39), achieving a poor performance value in the last period. This explains the worsening in its SCI value. Finally, the Catalan university that has improved the most for both indicators is the UB (+0.31 in the WCI and +0.55 in the SCI). In fact, jointly with UAB, they are the only universities that change their SCIs from the “poor” to the “fair” performance levels in the period analyzed. The only initial poor performance value for the UB (in the previously mentioned indicator) has improved. In fact, the highest improvement for this university takes place in the Drop-out rate, +1.30, being now in the “good” performance level. As in the Andalusian system, the poor performance values of the Catalan universities are concentrated in the International attractiveness indicator, and three of them have worsened their SCI in the period studied.

In the case of Madrid, the universities with the best WCIs in the final course are the UAM (1.90) and the UC3M (1.83). The former slightly worsened its SCI (−0.06), because of the International attractiveness indicator, which takes a lower value. Anyway, it is the only Madrid university with both SCI values over the reservation level. On the other hand, the UC3M has improved its SCI (+0.47), by improving its only poor performance value in the previously mentioned indicator. It is important to mention the case of URJC, which experiments the greatest improvement of both indicators. In fact, most of the teaching indicators of the URJC have improved, being the case of International attractiveness especially noteworthy (from 0 to 3). The greatest poor performance value of the URJC is now Foreign students in an Erasmus program (0.62). With respect to the strong indicator, it is convenient to point out the UCM, with a decrease of 0.68. Please note that in the initial course, jointly with the UAM, they were the only universities with a SCI over the reservation level. However, a bad performance in the Drop-out rate indicator in the final course (0.41) has caused this relevant worsening.

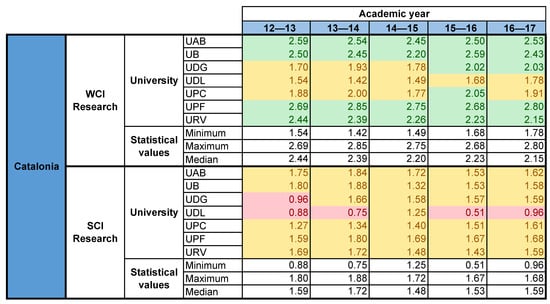

5.2. Research Mission

Comparing the results of the research mission with those of the teaching one, it can be observed that the differences between the three regions considered are even more notable. In general, the Catalan and Madrid systems show better values, both for the WCI and the SCI, in the initial and final academic years. For the Andalusian system, these values are, in general, worse.

Most of the universities considered have improved their research WCI along the period considered. The greatest improvements correspond to the UMA (+0.34), the UPM (+0.33) and the UDG (+0.32). The evolution experimented by these universities in the research field has been significant, and while in the initial course, among all of them, there were 9 cases of indicators under the reservation level, no one remains at the final course. Specifically, the UMA has experimented the greatest improvement in both the WCI (+0.34) and, significantly, the SCI (+0.99). This is because, in the initial course, the UMA had poor performance values for five out of the ten research indicators considered. In fact, the UMA has improved in seven research indicators, being the greatest improvements in Theses defended per doctor (+1.61) and Q1 Publications per doctor (+0.99). By sub-blocks, all the universities, except the URJC have improved in Publications per doctor, fourteen have improved in Other research activities, and the sub-block with a worst evolution is Projects, where only ten universities have improved.

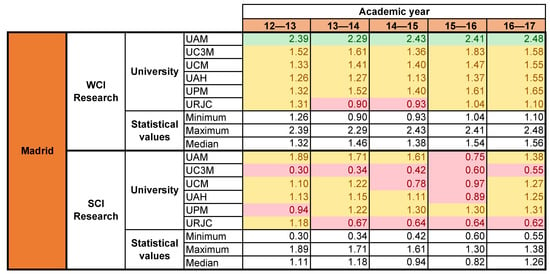

In the Andalusian system, the WCI values are in the range [0.78, 1.58] and [1.01, 1.76] for the academic years 2012–2013 and 2016–2017, respectively. This shows the general improvement, when a full compensation is allowed among the individual indicators. Conversely, if the poor performance values are analysed, it can be observed that the range of variability is greater now: the SCI values are in the range [0.14, 1.38] in the initial course and [0.64, 1.54] in the final course. This means that, during this period, the poor performance values have been improved. The Catalan system has the best results in the research mission for both periods. Its range of the WCI values has gone from [1.54, 2.69] to [1.78, 2.80], with five out of the seven universities having values better than the aspiration level at the final course (the UAB, the UB, the UDG, the UPF, the URV). The SCI values are initially in the range [0.88, 1.80] and, in the final course, the range is [0.96, 1.68]. Only the UDL university has some poor performance value in the 2016–2017 course, with a SCI value very close to the reservation level (0.96). Finally, the Madrid WCI is in the range of [1.26, 2.39] and [1.10, 2.48] in the initial and final course, respectively. Consequently, when a full compensation is allowed, the Madrid system performs better than the Andalusian system but worse than the Catalan system. On the other hand, the SCI are in the range [0.3, 1.89] and [0.55, 1.38] at the initial and final period, respectively. Let us now examine the universities of each region in further detail.

Concerning the Andalusian system, no university has a WCI over the aspiration level, but they all perform better than the reservation level at the final academic year (Figure 6). The UCO and the UGR have the best WCI values for both courses (2012–2013: 1.44 and 1.58; 2016–2017: 1.76 and 1.75, respectively). Neither of the two universities has any poor performance value, and in the last year they both have three indicators over the aspiration level (Citations per doctor, Theses defended per doctor and Official recognition of research for the UCO; International collaboration, Official recognition of research and Training grants and contracts per doctor for the UGR). Regarding the SCI, both universities are the only Andalusian universities with the SCI value over the reservation level for both courses. While the UGR is the only university of Andalusia with a (small) decrease (−0.08), the UCO has improved (+0.34). As mentioned before, within the Andalusian system, the UMA has experimented the greatest improvement (specially noticeable the Theses defended per doctor indicator, which had a poor performance value in the initial course, while in the final academic year, this indicator is over the aspiration level, 2.58). In general, the evolution of the Andalusian universities is good in the Publications sub-block (only the UHU and the UJAEN have worsened one of the indicators, Publications per doctor). In Other research activities, while all the universities improve the International collaboration and the Theses defended per doctor indicators, the UCO and US have had small worsening in Official recognition of research. The Participation in projects indicator presents, by far, the worst evolution (only the UCO increases). Finally, in the Projects sub-block, the general evolution is worse, with four universities worsening the Training grants and contracts per doctor indicator, and five universities worsening each of the other two indicators.

Figure 6.

Evolution in the research mission of the Andalusian public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

Most Catalan universities improve both their WCIs and SCIs (Figure 7). However, three universities slightly decrease both values (the UAB, the UB, the URV), although, they are over the aspiration level for the WCI and over the reservation level for the SCI, in the two years analyzed. The best university here is the UPF, which has the best results in both indicators in the final course. The WCI is close to the maximum value (2.80) and the final SCI is 1.68. It is important to mention that 8 out of the 10 indicators of the research mission obtain the maximum value of 3 in the final course, while the other two (Participation in projects, 1.40 and Official recognition of research, 1.70) obtain values under the aspiration levels. The UAB and the UB also obtain very good WCI values in the final course (2.53 and 2.43, respectively). However, both have worsened their WCI and SCI a bit (WCI: −0.06 and −0.07; SCI: −0.13 and −0.22, respectively). The UDG has had the greatest improvement of the Catalan universities in both WCI and SCI indicators (+0.32 and +0.63, respectively). On the one hand, the WCI value has improved mainly due to its improvement in 6 out of the 10 research indicators considered, being the greatest improvement located in the highest weighted research sub-block (all the indicators in the Publications sub-block are over the aspiration level in the final course). On the other hand, its SCI has improved mainly due to the improvement of the Official recognition of research indicator, which was under the reservation level in the initial course. Generally speaking, apart from the previously mentioned indicator, in the initial course there were only two more poor performance values in the research field (the UDL in International collaboration and the Theses defended per doctor), while only one poor performance value remains in the final course (the UDL in Participation in projects, very close to 1). As for the evolution, the behavior is similar to the Andalusian case. All the universities improve all the indicators of the Publications sub-block, while in the Other research activities, all the universities improve the International collaboration and the Theses defended per doctor indicators, the UAB, the UB and the URV have had worsening in Official recognition of research and, once again, the Participation in projects indicator presents the worst evolution (only the UPF increases). Finally, in the Projects sub-block, the general evolution is worse, with five universities worsening the National projects assigned per doctor indicator, and three universities worsening each of the other two indicators.

Figure 7.

Evolution in the research mission of the Catalan public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

Finally, all the Madrid universities have WCI values over the reservation level in both years, being the UAM the only university with values over the aspiration level (Figure 8). Regarding the SCI, only the UC3M and the URJC have values under the reservation level in the last academic year. In general, all universities improved their WCI and SCI values, except the UAM, which has worsened its SCI (−0.51) and the URJC, which has worsened both indicators (WCI: −0.21 and SCI: −0.56). The university with the best results in both indicators is the UAM, with a final WCI value of 2.48 and a slight improvement of 0.09 in the period analyzed. In the final course, the UAM does not have any poor performance value and it has eight out of the ten research indicators over the aspiration level. However, its SCI has experimented a marked decrease (−0.51), mainly due to the negative evolution in the European projects assigned per doctor indicator. The university with the second best WCI in the last year is the UPM (1.65). Within the Madrid system, this university has experienced the best improvement in both indicators (+0.33 in the WCI and +0.38 in the SCI). The UPM has evolved from having three poor performance values in the initial course (Citations per doctor, Theses defended per doctor and Training grants and contracts per doctor) to having none in the final period. As mentioned before, the URJC has worsened both WCI and SCI values. This is because it has worsened in six of the ten research indicators, and has evolved from having no poor performance value in the initial course, to having two, with very low values (Official recognition of research and Training grants and contracts per doctor). In the initial course, the Madrid universities had a total of five indicators below the reservation level and twelve over the aspiration level. In the final course, there are only three poor performance values, and fifteen indicators over the aspiration level. Finally, with respect to the evolution of the indicators, the trend is very similar to the other two regions. All the indicators belonging to the Publications sub-block have been improved, except the URJC, with decreases in Publications per doctor and Q1 Publications per doctor. With respect to the Other research activities sub-block, again the evolution of the Participation in projects indicator has been negative, with all the universities decreasing except the UAH and the UPM. All the universities have managed to improve the values of the other three indicators of this sub-block. Finally, in the Projects sub-block, all the universities have worsened their National projects assigned per doctor indicator, four of them have worsened the European projects assigned per doctor indicator, and only two of them obtain worse values for the Training grants and contracts per doctor indicator.

Figure 8.

Evolution in the research mission of the Madrid public university system from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017.

The analysis “intra” regions carried out previously, for both the teaching and research missions, shows the usefulness of jointly managing the WCI and SCI indicators. These indicators provide complementary information to detect improvement areas in each university that could remain unnoticed with other compensatory approaches. It must be borne in mind that the reference levels have been set taking into account all the universities of the Spanish public university system. Therefore, a nationwide comparison of the selected universities is taking place. This information could be used as one of the inputs for the discussion on the future of the university funding model in Spain, and thus in other European countries with similar characteristics.

In general, it is observed that Andalusian universities are quite homogeneous in both missions, although the UCO and UGR stand out slightly with better results in research than in teaching, while the opposite occurs for the UMA and UPO (see Figure A6 and Figure A9 in the Appendix B). In this sense, the different funding models applied in this region since 2002 have not significantly contributed to establish a diversified higher education system. These models have helped legitimizing the enormous public investment in Higher Education (5% of the Andalusian budgets) and have improved transparency and accountability. On the contrary, the Catalan university funding system (performance-based model) has been able to encourage institutions to strategically position themselves. According to [18], this is known as institutional profiling. Four Catalan universities have stood out over the others in research (UB, UAB, UPF and URV), while UDL excels in teaching (see Figure A7 and Figure A10 in the Appendix B). Finally, the fact that Madrid region has not applied a designed funding model since 2010 has led its universities to decide their own strategies without interference from the funder, the regional government. For instance, the research strategy of the university leaders of the UAM has led to the primacy in the research mission of this university over the rest of the universities in Madrid, while the university leaders of the URJC have promoted a strategy based on the teaching mission (see Figure A8 and Figure A11 in the Appendix B).

6. Discussion

In the previous subsection, the differences between the final and the initial situation of the universities in each mission, in a “intra” region fashion, have been studied. However, the Regional university funding policies are mainly designed to promote both teaching and research missions jointly, although there are certain differences in the emphasis given to research and teaching in the three funding models reviewed. In this sense, in order to analyze the impact of each regional university policy in its respective Public University Systems in terms of mission-mix (teaching and research) and the differences between the three regions considered, the evolution by regions along the whole period considered is depicted. Moreover, in view of the results, some policy messages are provided.

6.1. Dynamic Evolution by Regions

To conduct the regional analysis, one last aggregation step has been carried out (see Figure 9). The idea of this last step is to measure the impact of funding policies in the overall region performance. In order to obtain an overall composite indicator by region, which will be denoted by WWCI, the WCI of the universities belonging to each of the three Spanish regions has been considered. Please note that this aggregation is made for the teaching and research missions, separately (see Figure 2).

Figure 9.

Steps for constructing the WWCI by regions for each academic year.

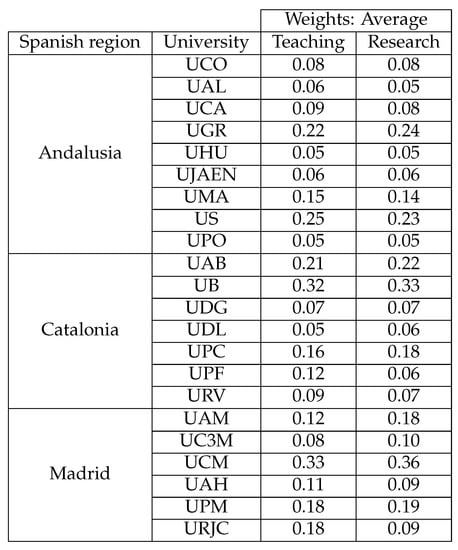

It should be noted that in order to construct the WWCI by region for each academic year, the universities belonging to each region have been aggregated assessing their relative importance (weight), using the total number of students, for the teaching mission, and the total number of faculty members holding a PhD, for the research mission. Figure A2 shows the average of the weights of the five academic years for the teaching and research missions.

The evolution graph is represented in Figure 10, where the overall performance (WWCI) of the teaching and research missions are represented, respectively in the horizontal and vertical axis.

Figure 10.

Dynamic evolution of the overall performance of the three regions in their teaching and research missions.

Moreover,

- The behavior of each region is represented by a line in the graph.

- Each point of the line represents the teaching (x component) and research (y component) performance for each academic year. In particular, the point with the arrow represents the teaching WWCI and research WWCI values for the given region in the final academic year 2016–2017, while the other extreme point of the line corresponds to the initial year, 2012–2013.

- A good region performance in both missions means being located further right and on the top.

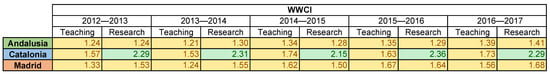

In Figure 10, it can be observed that, regarding the vertical axis, Catalonia is located higher than the other two regions. This indicates that Catalonia performs better than Andalusia and Madrid in the research mission, locating itself above the aspiration level for the five years analyzed. However, in the teaching mission, the three regions are located in the interval [1, 2], which means that all of them are performing better than the reservation level but worse than the aspiration level.

In the teaching mission, Madrid is the region with the greatest range of variation (0.43), while Andalusia has the smallest range (0.17). Likewise, Catalonia has the best initial and final situations (1.57 and 1.73, respectively). The second best initial and final situations correspond to Madrid (1.33 and 1.56, respectively). Concerning the research, the range of variation is quite similar for the three regions, although this range is slightly higher in the Catalan system than the other regions (Catalonia: 0.21, Madrid: 0.18, Andalusia: 0.16). Similarly to the teaching mission, Catalonia starts from the best initial situation in research and maintains this position in the final course (2.29 for both years). Once again, Madrid exceeds Andalusia in the two situations (initial: 1.53, 1.24 and final: 1.68, 1.41, respectively).

Let us analyze in detail the evolution of each region for discussion and potential recommendations. Throughout the period analyzed, Andalusia experienced a slight improvement in both missions. Specifically, in the teaching mission, this improvement has been steady throughout the five years, experiencing a small decrease from the first to the second year (of −0.02 points), and in the following years its WWCI has always been better than the previous one. The greatest improvement occurs between the courses 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 (+0.12 points). Regarding the research mission, the evolution of the overall performance has varied throughout the period analyzed. Although no sudden changes occurred, it can be observed that from the first to the second year, Andalusia has improved by +0.06, from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015 it has worsened by −0.02. From 2014–2015 to 2015–2016 it has experienced a very slight improvement, while from the fourth to the final academic year, Andalusia has experienced the best improvement in its WWCI (+0.11 points).

The changes observed in Catalonia are more noticeable. Unlike the Andalusian system, the overall performance of Catalonia has not maintained the same pattern of evolution throughout the period analyzed. Specifically, its teaching WWCI has worsened from the first to the second year by −0.03 and from 2014–2015 to 2015–2016 by −0.11 points. However, it has experienced a noticeable improvement from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015 (+0.20 points) and in the last year it has also slightly improved its teaching WWCI by +0.11 points. Similarly, there is no pattern of evolution in the research mission. In this case, Catalonia has experienced a very slight improvement in the first year (+0.02) and a noticeable improvement from 2014–2015 to 2015–2016 (+0.21 points). However, from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015, the Catalan system has experienced a worsening in its WWCI of −0.16 points and in the last year of −0.07 points. It should be noted that, despite these worsenings, Catalonia compared to the Andalusian and Madrid systems presents the best overall performance in both missions throughout the five years analyzed (except for the 2015–2016 course in the teaching mission, where the WWCI of Madrid slightly exceeds this of Catalonia, 1.67 and 1.63, respectively).

Finally, comparing the initial and final situations, it can be observed that Madrid has improved notably its overall performance in the teaching mission. However, this improvement has not been steady along the whole period considered. Specifically, the Madrid system shows a worsening in its WWCI in the first year of −0.08 points and in the last year of −0.11 points. However, from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015, Madrid has experienced the greatest improvement in its WWCI of the three regions in all the years considered. This improvement has been maintained in the following academic year, although with much less intensity (+0.05 points). Unlike the other two regions, Madrid has improved its WWCI in the research mission, for all the years analyzed, except a slight decrease (−0.05) from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015.

In general, the three regions have experienced worsenings in their teaching mission from 2012–2013 to 2013–2014 and all of them have improved from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015. Regarding the research mission, the three regions have worsened their WWCI from 2013–2014 to 2014–2015, while they have improved from 2012–2013 to 2013–2014 and from 2014–2015 to 2015–2016.

6.2. Policy Message and Funding Models

In Figure 10, it can be observed that the points representing the different performances of Catalonia’s public university system are, in general, further away from the bisector line, indicating a greater difference between the research and the teaching performance (in favor of the former). Additionally, the Catalonia public system seems to offer better results than the other two public university systems. It must be reminded that in the period analyzed, the performance-based funding model of the Catalonian system allocated around 40% based on teaching and research outcomes, although perhaps with a predominance of the research mission. Nevertheless, the implemented model since 2002 has rewarded relatively balanced teaching and research outputs, driving to a clear improvement in teaching (although there is still room to improve) and very prominent position in research in the considered period. This result can be interpreted as a sign to policy messages for the Catalan government. Given its high level in the research mission within the national scene, the strategy to be followed by the Catalan authorities would be design a new funding model that continues to value research outputs and its productivity and improves teaching outcomes.

Secondly, in the Andalusian public university system, as can be observed in Figure 10, the points are practically on the bisector line for the two WWCIs, which indicates a fairly similar behavior in both missions along the whole period considered. Relating to the impact of funding model, the fact that the Andalusian system is on the bisector line, may be reflecting that the nine universities are homogeneous in the sense that they are all comprehensive (slight differences in the subject-mix) and the funding system does not differentially reward the research outputs versus the teaching ones. In fact, its funding model allocates less than 7.5% of the strategic funding to goals in the period analyzed, and in the main basic funding block (more than 90%), neither of the two teaching and research functions prevails and what predominates is an allocation based on the academic demand. The behaviour of staff costs (or inputs consumption) is consolidated over the period. The funding model adds quite a balance in the funding that each of the universities receives and this circumstance gives stability to the results in teaching and research of the Andalusian Public System (as shown by the two indicators represented in Figure 10). It cannot be concluded that the different evolutions in the Andalusian Public System of WWCIs are due to the small revisions of the university funding system in Andalusia, which has been very stable over time. With regard to the policy messages, it is possible that the Andalusian government will maintain its balance between the two missions in the short term. However, in the long term, regional higher education authorities may choose to bet on one of them or both, teaching or research, by introducing a new funding model that seeks institutional profiling where some universities are empowered in teaching and others are empowered in research.

Finally, with regard to the Madrid public university system, it can be observed that the points are close to the bisector line for the two WWCIs in the last three years, which suggests smaller differences between both missions. Significantly, at the beginning of the period, Madrid presented a more research oriented projection, but the universities of the region have improved substantially their teaching WWCI along the period analysed. With respect to the funding model, in the case of the Madrid system, there is a great variability (and an erratic behavior) in the dynamic evolution of the two WWCIs of teaching and research. This can result, on the one hand, from the heterogeneity of the universities of Madrid, in terms of their performance in the two missions (UAM, UCM and UC3M are more research intensive universities, while URJC is more teaching intensive university) and, on the other hand, from the fact that there is no funding model that allocates a portion of the public funding based on teaching and research results. As a policy message, Madrid’s public university system may continue to bet on improving teaching, but if the regional government needs to enhance research to reach the level of the Catalan university system and other similar university systems in Europe, one solution is to introduce a road-map with new performance agreements that promote both research productivity and research activities, especially in those institutions that are research intensive universities.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, the evolution of the performance of the public universities of several Spanish regions has been studied, in order to assess the impact of their basically different funding policies. To this end, the use of the MRP-WSCI methodology is proposed to build composite performance indicators for each university, because of three reasons. First, by using reference levels, the performance of the universities is established in comparison to others (in this case, all the Spanish universities, but other, more global, levels can be used). Second, the joint consideration of the compensatory (weak) and non-compensatory (strong) composite indicators allows us to obtain, not only an overall performance measure, but also warning signals about aspects that are behaving worse, which can be used by policy makers in decision making processes. Finally, the methodology makes it possible to consider the dynamic dimension, and to obtain a clear picture of the evolution of the universities along the period considered.

The findings of this research can be particularly useful for setting effective policy actions able to promote the university performance of each territory by levering on funding systems (and incentives). In a broader perspective, the paper significantly contributes to the policy debate by informing governments and academic authorities on the most relevant incentives (via indicators chosen) of regional funding systems influencing university results in teaching and research. This study offers new instruments (through composite indicators obtained using multi-criteria techniques) to help policy makers understand and possibly address interregional disparities in university performance, which are particularly evident in the three public university systems analyzed. Therefore, the work employs a novel analytical approach that ranges from statistical techniques to an exhaustive and rigorous analysis of the contribution of financing models to increasing the performance of universities in three Spanish case studies. Of course, this methodology can be easily adapted to other university systems with their own peculiarities, collected in other indicator systems and, possibly, reference levels.

In this particular case study, the purpose of the description and comparison “intra” regions is to use the WCI and SCI in the three Spanish regions, in both the teaching and research missions, as one of the inputs for the discussion on the future of the funding model in Spain and thus in other European countries with similar size in future research. The results have allowed us to demonstrate that there are different behaviors in teaching and research (“intra” regions) and to verify the usefulness of the composite indicators (WCI and SCI in teaching and research) to determine what has happened within each university system, comparing the first and last years. From a global perspective, it can be concluded that the teaching performance of the Andalusian, Catalan and Madrid universities has improved globally during the period analyzed. However, all of them still have room for improvement, as most are at the “fair” performance level. In this sense, the additional formula funding or the new performance agreements must focus on the teaching mission in the three systems. On the other hand, the detailed analysis has revealed some university institutions with interesting behaviors, some with sustained trends throughout the analyzed period and other institutions with more erratic behaviors, within the same system despite having the same funding model.