Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method to Functionally-Graded, Thin, Circular Piezoelectric Plates

Abstract

1. Introduction

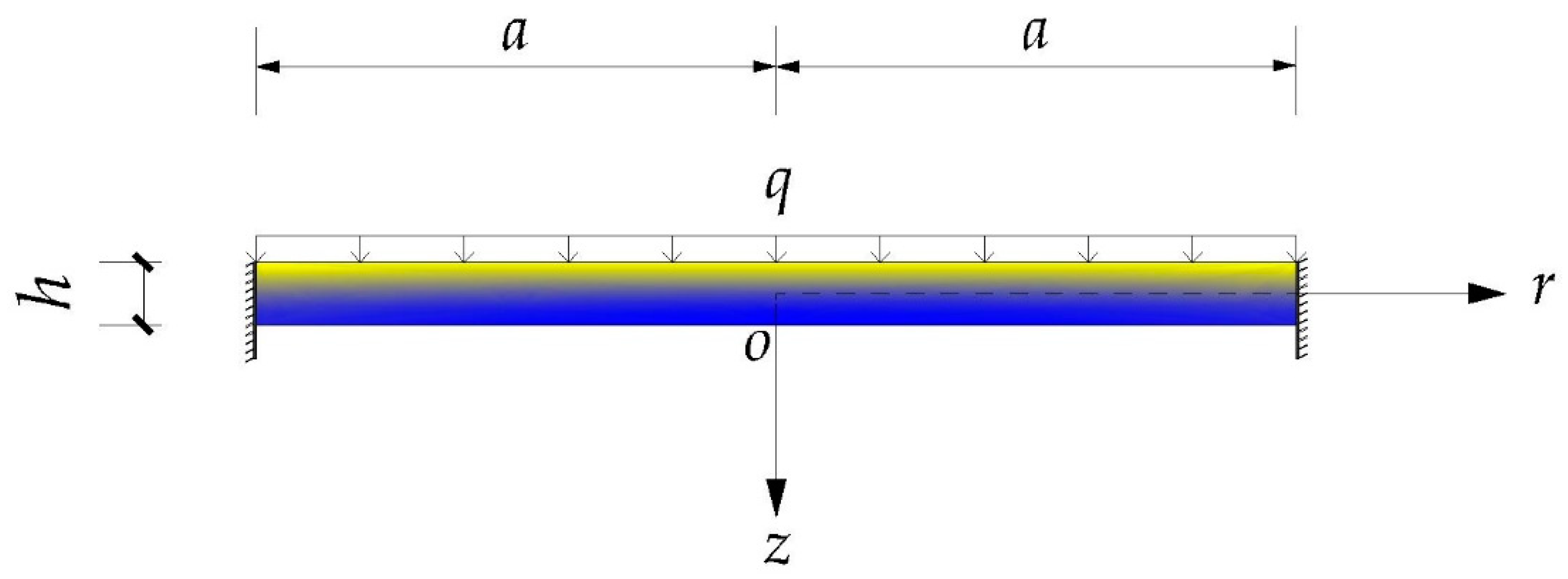

2. Mechanical Model and Basic Equations

3. Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method

3.1. Nondimensionalization and Perturbation Expansions

3.2. Zero-Order Perturbation Solution

3.3. First-Order Perturbation Solution

4. Numerical Simulation and Comparison with Perturbation Solution

4.1. Numerical Simulation

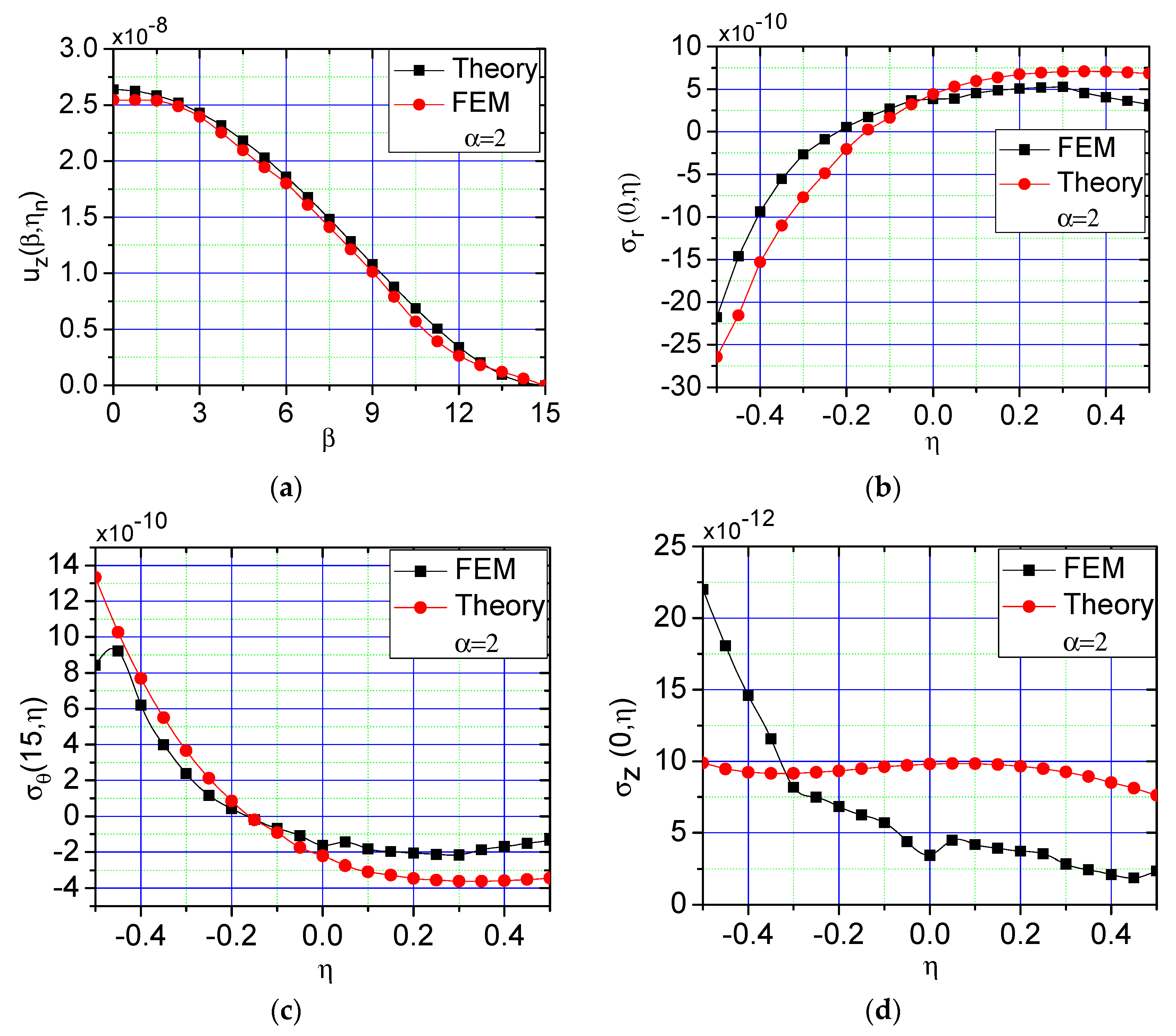

4.2. Comparison with Perturbation Solution

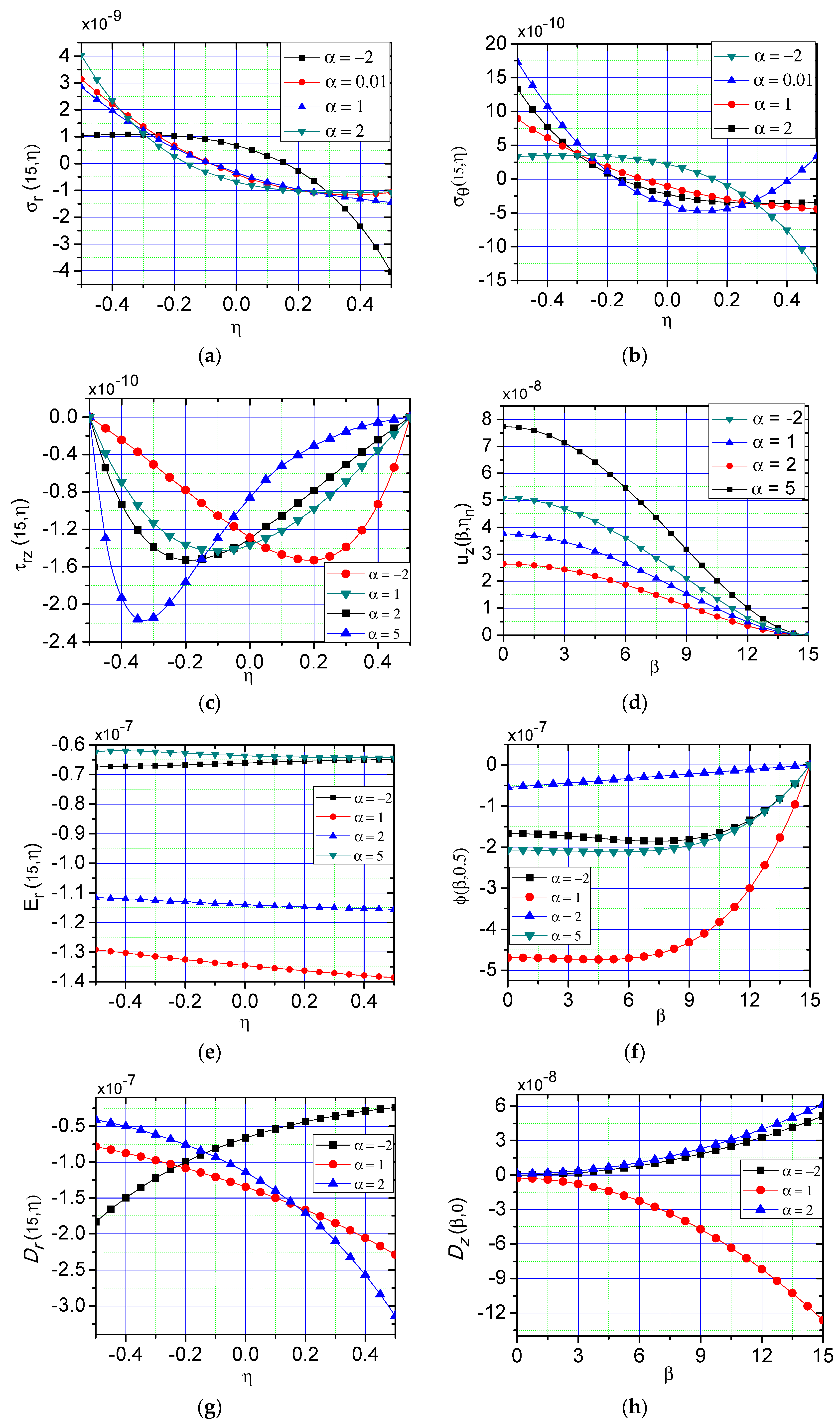

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Effect of Gradient Index on Solution

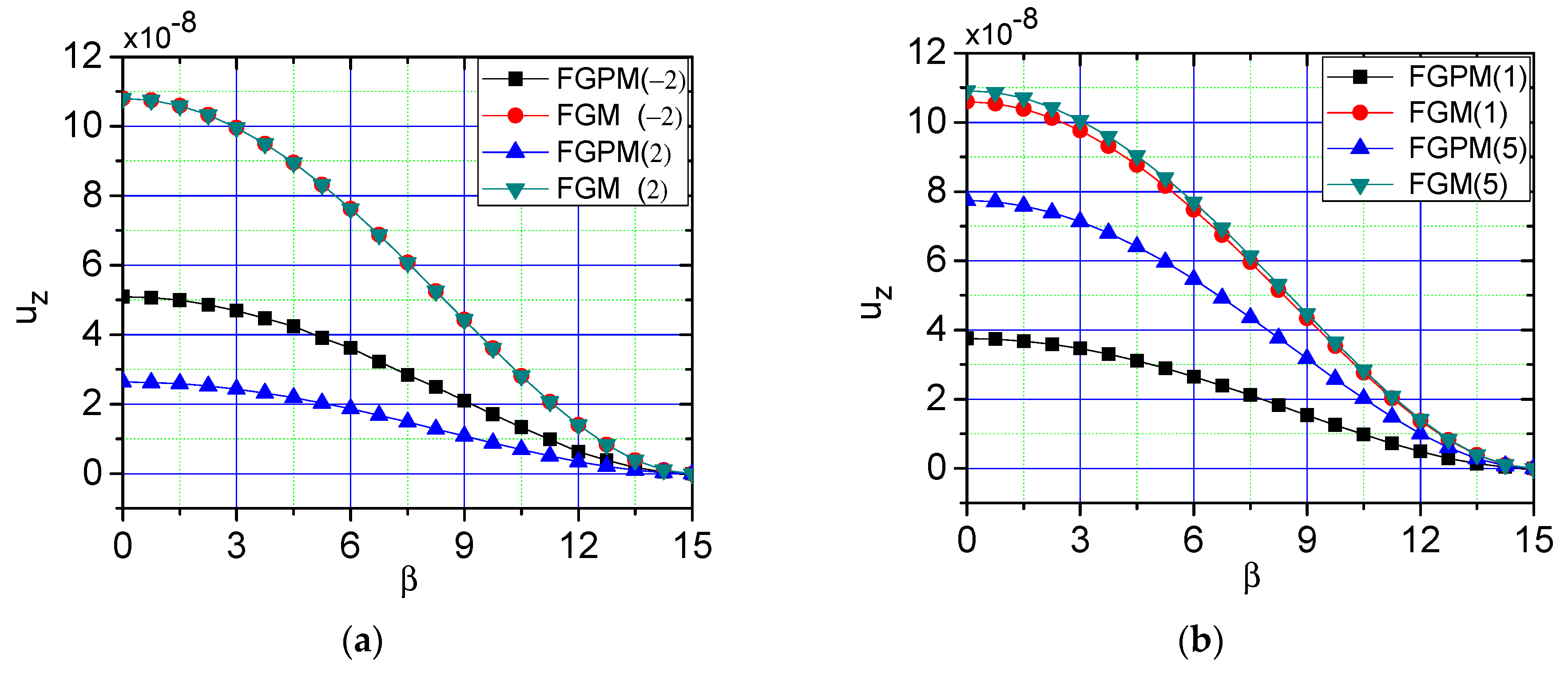

5.2. Deflection Comparison Between FGPM and FGM Plates

6. Conclusions

- (i)

- Adopting the three piezoelectric coefficients as perturbation parameters follows the basic idea of perturbation theory—i.e., if pure FGM plates without piezoelectric effects are taken as the undisturbed system, and the piezoelectric effect may be introduced as a kind of disturbance, then FGPM plates may be regarded as a disturbed system; thus, the solution for pure FGM plates may be easily obtained as a zero-order solution of the disturbed system.

- (ii)

- In our perturbation, two stress functions and one electrical potential function were selected as basic functions. It was found that in the zero-order perturbation solution, only stress functions were not zero; thus, the zero-order solution actually corresponded to the elastic solution concerning elastic stress, elastic strain, and elastic displacement, this conclusion is consistent with the former conclusion: while in the first-order perturbation solution, only the electrical potential function was not zero; thus, the first-order solution actually corresponded to the electrical solution, concerning electrical potential, electrical field intensity, and electrical displacement.

- (iii)

- The deformation magnitude of FGPM plates is generally smaller than that of corresponding FGM plates, showing the well-known piezoelectric stiffening effect. From the point of view of energy conservation and transformation, a portion of the work done by applied external loads is transformed into electrical energy, due to the piezoelectric effect, thus decreasing elastic strain energy stored in FGPM plates and resulting in the corresponding decrease in deformation magnitude.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Zero-Order Perturbation Solution

| Gradient Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.157 | 0 | −0.157 | −0.307 |

| Gradient Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (×1010) | −2.517 | −2.070 | 2.517 | −1.252 |

| (×1010) | 1.830 | 1.647 | 1.830 | 1.879 |

Appendix B. First-Order Perturbation Solution

References

- Rao, S.S.; Sunar, M. Piezoelectricity and its use in disturbance sensing and control of flexible structures: A survey. Appl. Mech. Rev. 1994, 47, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohanka, M. Overview of piezoelectric biosensors, immunosensors and DNA sensors and their applications. Materials 2018, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltanrezaee, M.; Bodaghi, M.; Farrokhabadi, A.; Hedayati, R. Nonlinear stability analysis of piecewise actuated piezoelectric microstructures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2019, 160, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, K.; Bui, T.Q. New analytical solutions for modified polarization saturation models in piezoelectric materials. Meccanica 2019, 54, 2443–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.M.; Kahn, M.; Moy, W. Piezoelectric ceramics with functional gradients: A new application in material design. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1996, 79, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, W.F., II; Wan, S.; Bowman, K.J. Functionally-graded piezoelectric ceramics. Mater. Sci. Forum 1999, 308–311, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taya, M.; Almajid, A.A.; Dunn, M.; Takahashi, H. Design of bimorph piezo-composite actuators with functionally-graded microstructure. Sens. Actuators A 2003, 107, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.J.; Ding, H.J.; Chen, W.Q. Piezoelasticity solutions for functionally-graded piezoelectric beams. Smart Mater. Struct. 2007, 16, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Yu, T. Electroelastic analysis of functionally-graded piezoelectric material beam. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2008, 19, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodaghi, M.; Damanpack, A.R.; Aghdam, M.M.; Shakeri, M. Geometrically non-linear transient thermo-elastic response of FG beams integrated with a pair of FG piezoelectric sensors. Compos. Struct. 2014, 107, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.X.; Shi, Z.F. Steady-State forced vibration of functionally-graded piezoelectric beams. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2011, 22, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Wang, Y.Z.; Shi, S.J.; Sun, J.Y. An electroelastic solution for functionally-graded piezoelectric material beams with different moduli in tension and compression. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 1649–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeri, M.; Mirzaeifar, R. Static and dynamic analysis of thick functionally-graded plates with piezoelectric layers using layerwise finite element model. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2009, 16, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F. Analytical investigation on vibrations and dynamic response of functionally-graded plate integrated with piezoelectric layers in thermal environment. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2013, 20, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, G.M.; Plotnikova, S.V. An analytical approach to three-dimensional coupled thermoelectroelastic analysis of functionally-graded piezoelectric plates. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2017, 28, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeigloo, A. Thermo elasticity solution of functionally-graded, solid, circular, and annular plates integrated with piezoelectric layers using the differential quadrature method. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2018, 25, 766–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Asanjarani, A. Semi-analytical mechanical and thermal buckling analyses of 2D-FGM circular plates based on the FSDT. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2019, 26, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeigloo, A. Static analysis of a functionally-graded cylindrical shell with piezoelectric layers as sensor and actuator. Smart Mater. Struct. 2009, 18, 065004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehralian, F.; Beni, Y.T.; Ansari, R. Size dependent buckling analysis of functionally-graded piezoelectric cylindrical nanoshell. Compos. Struct. 2016, 152, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglar, M.; Mirdamadi, H.R. Configuration optimization of piezoelectric patches attached to functionally-graded shear-deformable cylindrical shells considering spillover effects. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2016, 27, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Q.; Zhu, C.S.; Liu, J.X.; Zhao, J. Surface energy effect on nonlinear buckling and postbuckling behavior of functionally-graded piezoelectric cylindrical nanoshells under lateral pressure. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 045017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari Dezfoli, A.R.; Mehrabian, M.A.; Saffaripour, M.H. Two dimensional temperature distributions in plate heat exchangers: An analytical approach. Mathematics 2015, 3, 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, V.; Muradoğlu, Z. A mathematical model and numerical solution of a boundary value problem for a multi-structure plate. Mathematics 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gorder, R.A. Analytical method for the construction of solutions to the Föppl-von Kármán equations governing deflections of a thin flat plate. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2012, 47, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.J. The bending of a thin circular plate. Philos. Mag. 1931, 12, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.Z. Large deflection of a circular clamped plate under uniform pressure. Chin. J. Phys. 1947, 7, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.C. On the large deflection of a circular plate under combined action of uniformly distributed load and concentrated load at the center. Chin. J. Phys. 1954, 10, 383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.; DaDeppo, D.A. A new approach to the analysis of shells, plates and membranes with finite deflections. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 1974, 9, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C. Large deflection of circular plate under compound load. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 1983, 4, 791–804. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Kuang, J.C. The perturbation parameter in the problem of large deflection of clamped circular plates. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 1981, 2, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L. Free-parameter perturbation method. In Proceeding for Celebrating 90th Birthday of Professor Chien Wei-Zang; Zhou, Z.W., Ed.; Shanghai University Press: Shanghai, China, 2003; pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.L.; Li, Q.Z. Free-parameter perturbation-method solutions of the nonlinear stability of shallow spherical shells. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 2004, 25, 963–970. [Google Scholar]

- Nowinski, J.L.; Ismail, I.A. Application of a multi-parameter perturbation method to elastostatics. Dev. Theor. Appl. Mech. 1965, 2, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W.Z. Second order approximation solution of nonlinear large deflection problem of Yongjiang Railway Bridge in Ningbo. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 2002, 23, 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.T.; Chen, S.L. Biparametric perturbation solution of large deflection problem of cantilever beams. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 2006, 27, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Cao, L.; Li, Z.Y.; Hu, X.J.; Sun, J.Y. Nonlinear large deflection problems of beams with gradient: A biparametric perturbation method. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 219, 7493–7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Cao, L.; Sun, J.Y.; Zheng, Z.L. Application of a biparametric perturbation method to large-deflection circular plate problems with a bimodular effect under combined loads. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2014, 420, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.Z.; Sun, J.Y.; Zheng, Z.L. A biparametric perturbation method for the Föppl-von Kármán equations of bimodular thin plates. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2017, 455, 1688–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.X.; Liu, G.H.; Sun, J.Y. Application of biparametric perturbation method to functionally-graded thin plates with different moduli in tension and compression. ZAMM J. Appl. Math. Mech. 2019, 99, e201800213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, F.; Nosier, A.; Sharifi, M.; Ghezelbash, F. On perturbation method in mechanical, thermal and thermo-mechanical loadings of plates: Cylindrical bending of FG plates. ZAMM J. Appl. Math. Mech. 2016, 96, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.S.; He, X.T.; Shi, S.J.; Yang, Z.X.; Sun, J.Y. A multi-parameter perturbation solution for functionally-graded piezoelectric cantilever beams under combined loads. Materials 2018, 11, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.S.; He, X.T.; Liu, G.H.; Sun, J.Y.; Zheng, Z.L. Application of perturbation idea to well-known Hencky problem: A perturbation solution without small-rotation-angle assumption. Mech. Res. Commun. 2017, 83, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.J.; Xu, B.H. General solutions of axisymmetric problems in transversely isotropic body. Appl. Math. Mech. (Engl. Ed.) 1998, 9, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, H.J.; Li, X.Y.; Chen, W.Q. Analytical solutions for a uniformly loaded circular plate with clamped edges. J. Zhejiang Univ. Science A 2005, 6, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.T.; Yang, Z.X.; Jing, H.X.; Sun, J.Y. One-dimensional theoretical solution and two-dimensional numerical simulation for functionally-graded piezoelectric cantilever beams with different properties in tension and compression. Polymers 2019, 11, 1728. [Google Scholar]

| Elastic Constants (10−12 m2·N−1) | Piezoelectric Constants (10−12 C·N−1) | Dielectric Constants (10−8 F·m−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12.4 | −4.05 | −5.52 | 16.1 | 39.1 | −135 | 300 | 525 | 1.301 | 1.151 |

| Elastic Constants | Piezoelectric Constants | Dielectric Constants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.327 | −0.445 | 1.298 | 3.153 | −0.336 | 0.747 | 1.307 | 1 | 0.885 |

| Theoretical solutions | 2.637 | −26.082 | 13.415 |

| Numerical results | 2.599 | −22.143 | 9.582 |

| Relative errors | 1.44% | 15.10% | 28.57% |

| 0.157 | −0.082 | −0.157 | −0.307 | |

| FGPM | 0.509 | 0.375 | 0.264 | 0.774 |

| FGM | 1.081 | 1.060 | 1.081 | 1.092 |

| FGPM Plates | FGM Plates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a(×10−7) | b(×10−10) | c(×10−12) | a(×10−7) | b(×10−10) | c(×10−12) | |

| 0.509 | −4.531 | 1.007 | 1.081 | −9.607 | 2.135 | |

| 0.375 | −3.337 | 0.742 | 1.060 | −9.421 | 2.093 | |

| 0.264 | −2.344 | 0.521 | 1.081 | −9.607 | 2.135 | |

| 0.774 | −6.884 | 1.530 | 1.092 | −9.702 | 2.156 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, X.-T.; Yang, Z.-X.; Li, Y.-H.; Li, X.; Sun, J.-Y. Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method to Functionally-Graded, Thin, Circular Piezoelectric Plates. Mathematics 2020, 8, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8030342

He X-T, Yang Z-X, Li Y-H, Li X, Sun J-Y. Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method to Functionally-Graded, Thin, Circular Piezoelectric Plates. Mathematics. 2020; 8(3):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8030342

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Xiao-Ting, Zhi-Xin Yang, Yang-Hui Li, Xue Li, and Jun-Yi Sun. 2020. "Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method to Functionally-Graded, Thin, Circular Piezoelectric Plates" Mathematics 8, no. 3: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8030342

APA StyleHe, X.-T., Yang, Z.-X., Li, Y.-H., Li, X., & Sun, J.-Y. (2020). Application of Multi-Parameter Perturbation Method to Functionally-Graded, Thin, Circular Piezoelectric Plates. Mathematics, 8(3), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/math8030342