Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling for Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Robust Framework for Stiff PDEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

Problem Overview and Proposed Method

- We propose a novel curriculum-enhanced adaptive sampling framework for PINNs, which dynamically integrates curriculum learning with residual-based adaptive refinement. By progressively introducing stiffness through the curriculum regularization while adaptively refining collocation points based on PDE residuals, our approach robustly resolves sharp gradients and stiff regions.

- We introduce four adaptive sampling algorithms: Curriculum-Enhanced RAR-Greedy (CE-RARG), Curriculum-Enhanced RAR-Distribution (CE-RARD), and their novel difficulty-aware counterparts, CED-RARG and CED-RARD. The difficulty-aware variants employ a stiffness-adaptive scheme that dynamically adjusts the number of refinement loops for each curriculum stage based on its relative difficulty.

- Through systematic experiments on five challenging stiff PDE systems (the Allen–Cahn, Burgers’ I, Burgers’ II, Korteweg–de Vries, and Reaction equations) across varying nonlinearity regimes, we demonstrate that our methods dramatically outperform standard PINNs and curriculum-only approaches. Notably, CED-RARD achieves error reductions of up to two orders of magnitude on the Burgers’ and KdV equations, while CED-RARG proves most effective on the Allen–Cahn and Reaction problems.

- We provide a publicly available implementation, including code, datasets, and reference solutions to ensure full reproducibility and facilitate future research in PINNs for stiff PDEs.

2. Materials and Methods

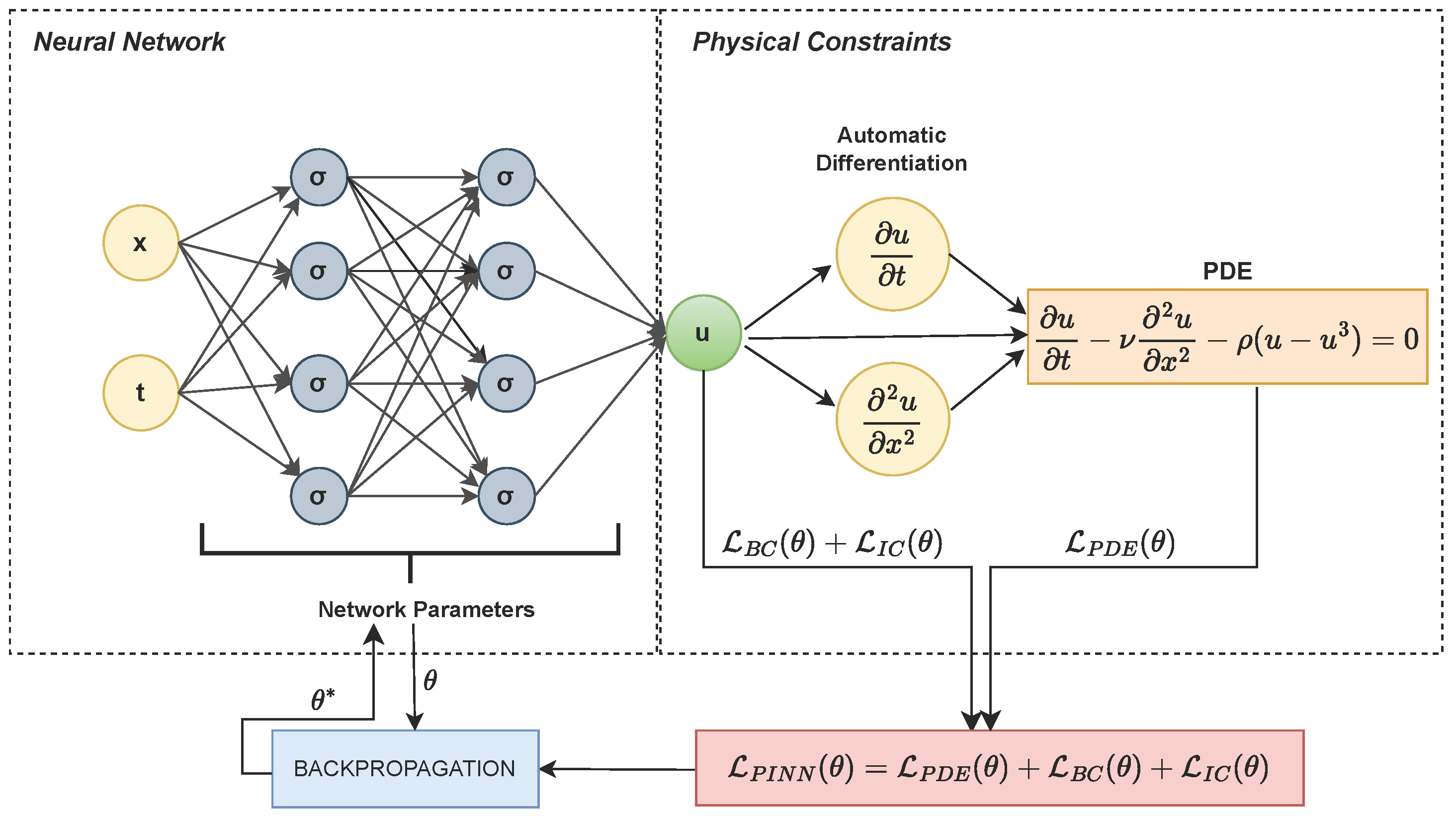

2.1. Physics-Informed Neural Networks

2.2. Curriculum Learning in PINNs

2.3. Residual-Based Adaptive Sampling Methods

2.4. Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling

- CE-RARG (outlined in Algorithm 1) adds a fixed number of residual-based collocation points at each curriculum stage using a greedy strategy. It focuses on areas with the highest residuals.

- CED-RARG extends CE-RARG by adjusting the number of added high residual points dynamically based on task difficulty estimates.

- CE-RARD (outlined in Algorithm 2) uses a probabilistic sampling strategy based on residuals to select collocation points for each stage, maintaining consistency with the curriculum.

- CED-RARD builds on CE-RARD by dynamically adjusting the number of refinement loops per stage based on the ratio of mean residuals between successive tasks.

| Algorithm 1 CE-RARG: RAR with Curriculum Learning |

|

| Algorithm 2 CE-RARD: RARD with Curriculum Learning |

|

| Algorithm 3 CED-RARG: Dynamic RARG with Curriculum Learning |

|

| Algorithm 4 CED-RARD: Dynamic RARD with Curriculum Learning |

|

3. Experiments

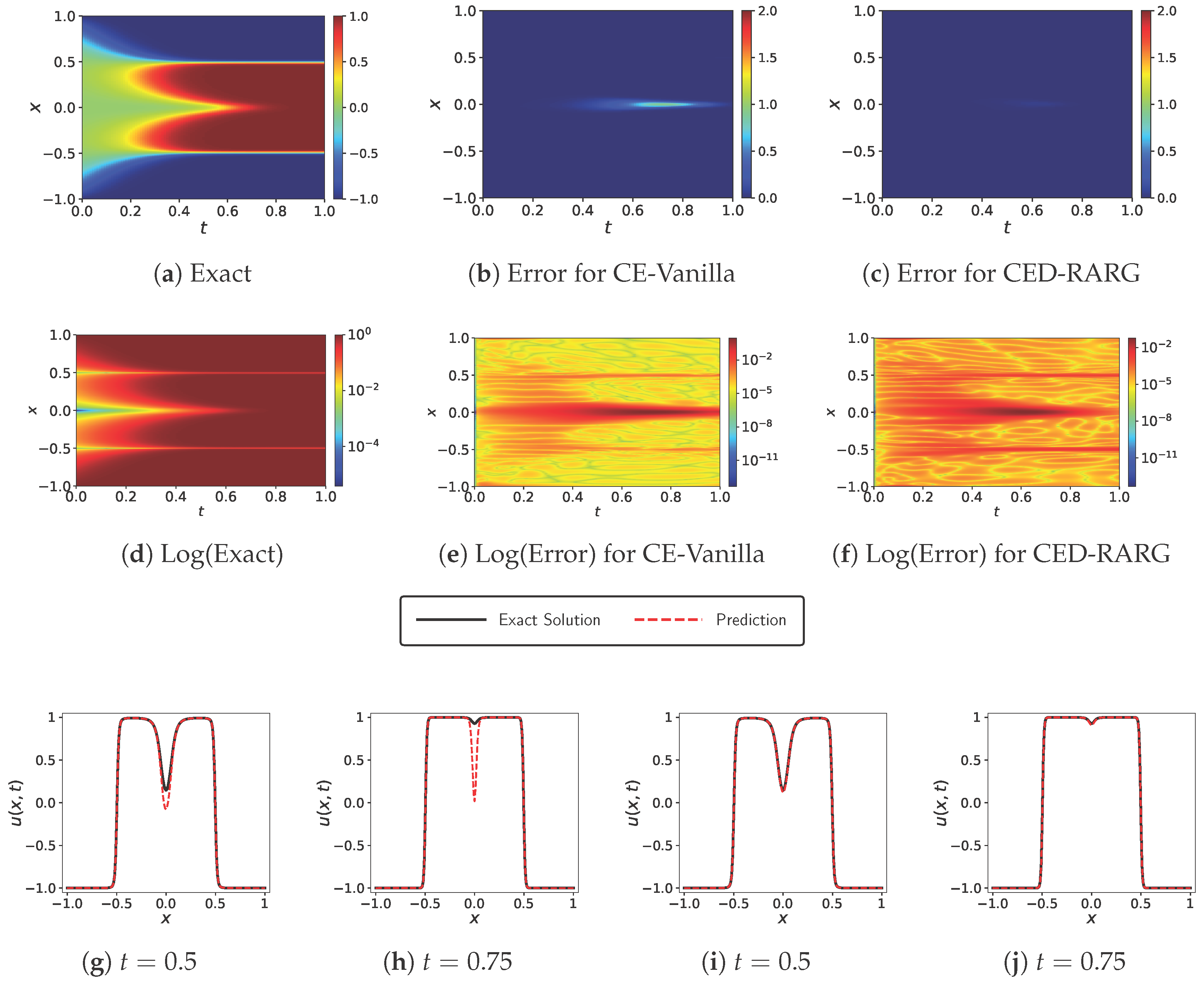

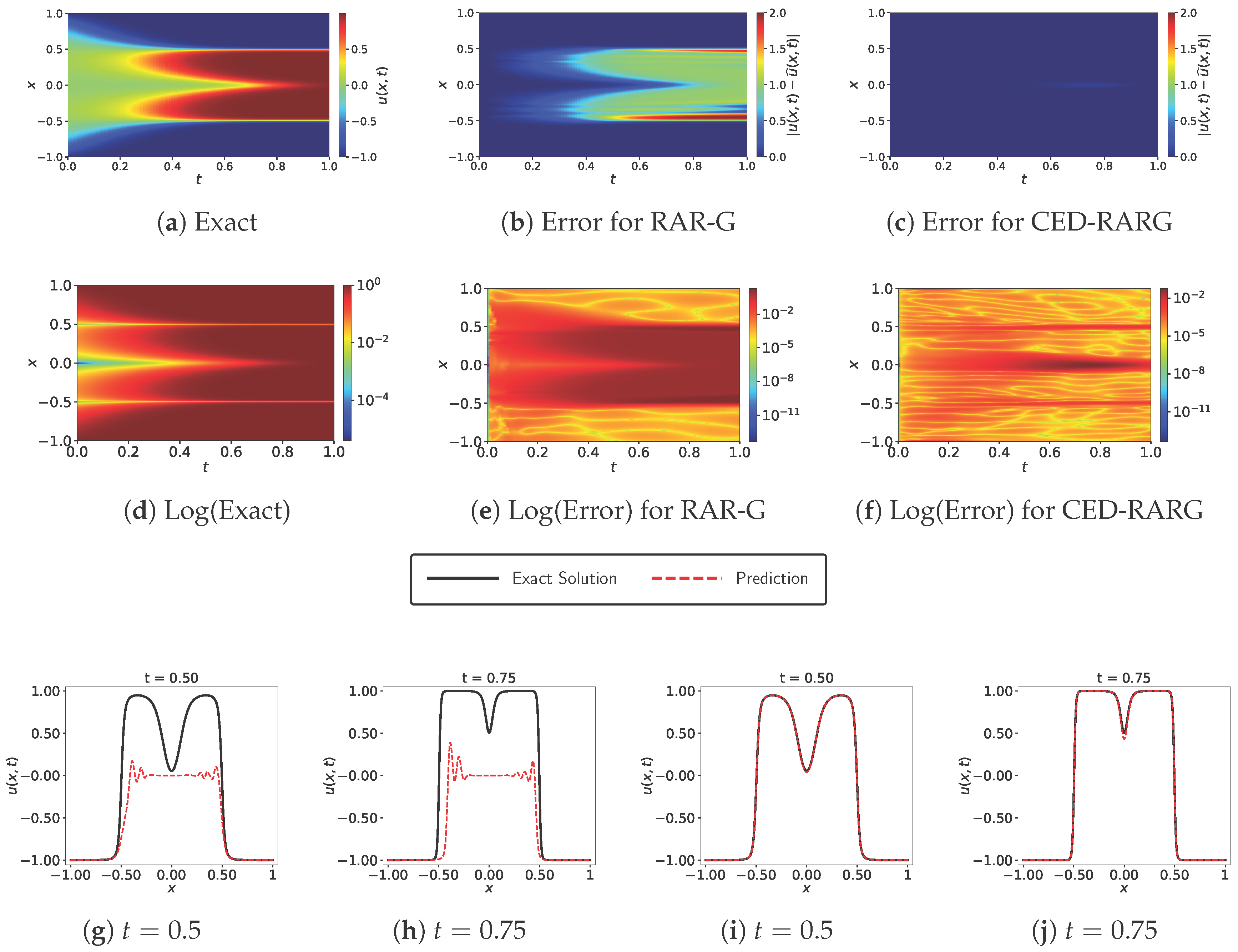

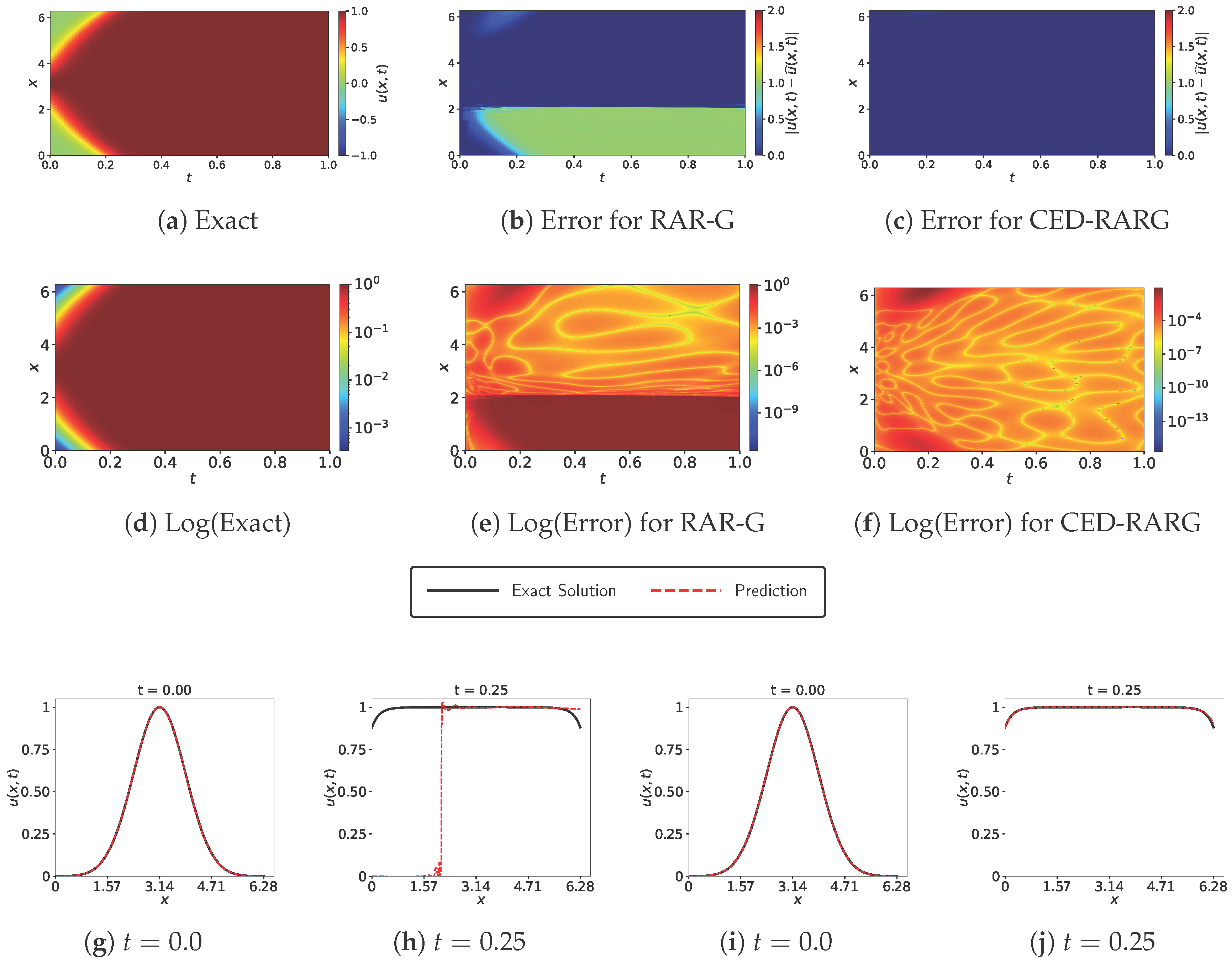

3.1. Allen–Cahn Equation

3.2. Ablation Study: Computational Cost vs. Accuracy for Static (CE-) and Dynamic (CED-) Strategies

3.3. Ablation Study on Stability and Robustness

3.4. Burgers’ Equation-I

3.5. Burgers’ Equation-II

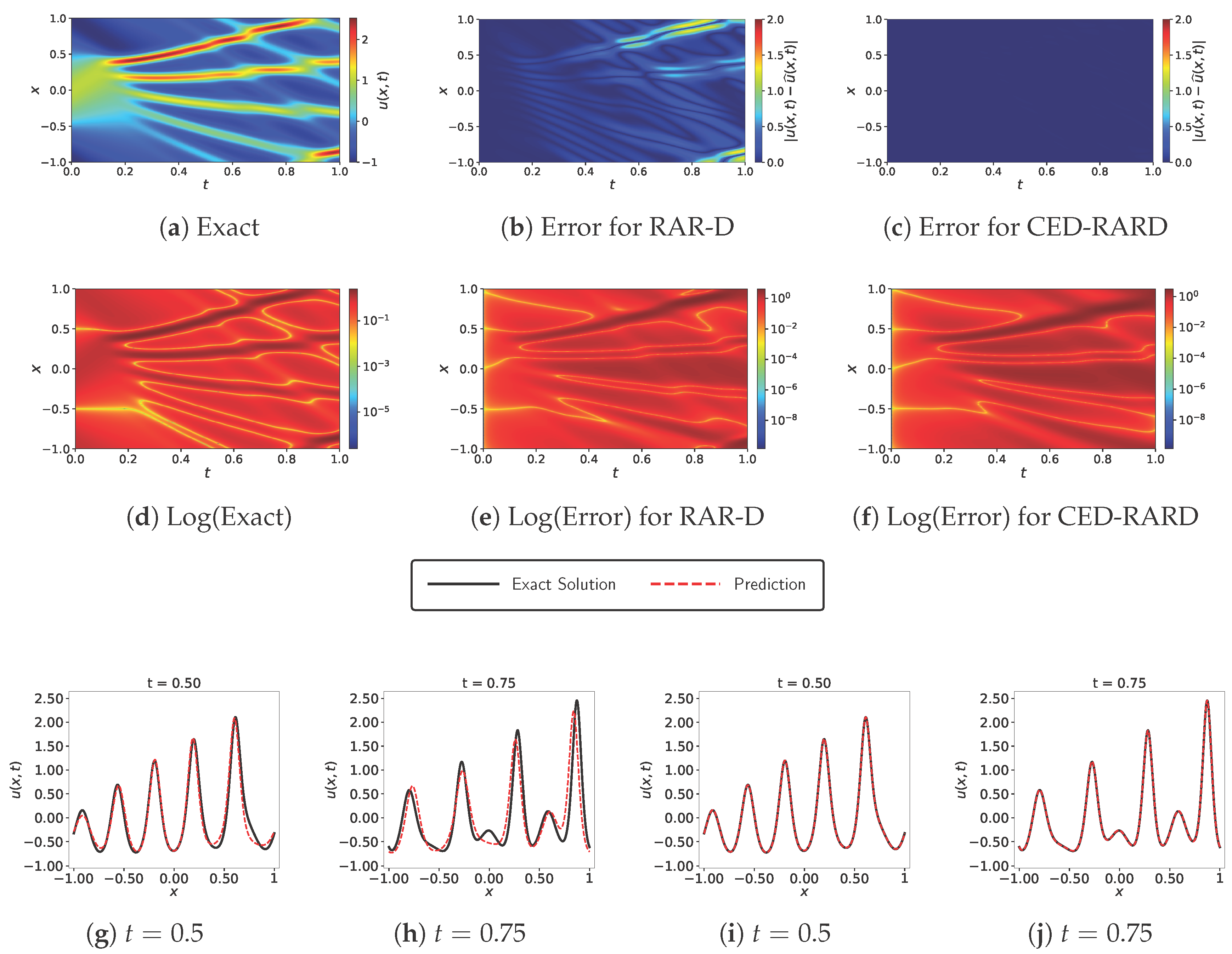

3.6. Korteweg–De Vries Equation

3.7. Reaction Equation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angermueller, C.; Pärnamaa, T.; Parts, L.; Stegle, O. Deep learning for computational biology. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016, 12, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, S.; Di Cola, V.S.; Giampaolo, F.; Rozza, G.; Raissi, M.; Piccialli, F. Scientific Machine Learning Through Physics–Informed Neural Networks: Where We Are and What’s Next. J. Sci. Comput. 2022, 92, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karniadakis, G.E.; Kevrekidis, I.G.; Lu, L.; Perdikaris, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 422–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Yazdani, A.; Karniadakis, G.E. Hidden fluid mechanics: Learning velocity and pressure fields from flow visualizations. Science 2020, 367, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, E.; Dao, M.; Karniadakis, G.E.; Suresh, S. Analyses of internal structures and defects in materials using physics-informed neural networks. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk0644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahli Costabal, F.; Yang, Y.; Perdikaris, P.; Hurtado, D.E.; Kuhl, E. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Cardiac Activation Mapping. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, T.; Subramanian, S.; Harrington, P.; Pathak, J.; Mardani, M.; Hall, D.; Miele, A.; Kashinath, K.; Anandkumar, A. FourCastNet: Accelerating Global High-Resolution Weather Forecasting Using Adaptive Fourier Neural Operators. In Proceedings of the Platform for Advanced Scientific Computing Conference, Davos, Switzerland, 26–28 June 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baydin, A.G.; Pearlmutter, B.A.; Radul, A.A.; Siskind, J.M. Automatic Differentiation in Machine Learning: A Survey. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2018, 18, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Chintala, S.; Chanan, G.; Yang, E.; DeVito, Z.; Lin, Z.; Desmaison, A.; Antiga, L.; Lerer, A. Automatic differentiation in PyTorch. In NIPS 2017 Workshop on Autodiff; NIPS: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Teng, Y.; Perdikaris, P. Understanding and Mitigating Gradient Flow Pathologies in Physics-Informed Neural Networks. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2021, 43, A3055–A3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sankaran, S.; Perdikaris, P. Respecting causality for training physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2024, 421, 116813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tancik, M.; Srinivasan, P.; Mildenhall, B.; Fridovich-Keil, S.; Raghavan, N.; Singhal, U.; Ramamoorthi, R.; Barron, J.; Ng, R. Fourier Features Let Networks Learn High Frequency Functions in Low Dimensional Domains. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 7537–7547. [Google Scholar]

- Sitzmann, V.; Martel, J.N.P.; Bergman, A.W.; Lindell, D.B.; Wetzstein, G. Implicit Neural Representations with Periodic Activation Functions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 7462–7473. [Google Scholar]

- McClenny, L.D.; Braga-Neto, U.M. Self-adaptive physics-informed neural networks. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 474, 111722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnapriyan, A.; Gholami, A.; Zhe, S.; Kirby, R.; Mahoney, M.W. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 26548–26560. [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, M.; Krukowski, P.; Paszyńska, A.; Paszyński, M. Comparison of Physics Informed Neural Networks and Finite Element Method Solvers for advection-dominated diffusion problems. J. Comput. Sci. 2024, 81, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A.D.; Karniadakis, G.E. Extended Physics-Informed Neural Networks (XPINNs): A Generalized Space-Time Domain Decomposition Based Deep Learning Framework for Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2020, 28, 2002–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Karniadakis, G.E. Gradient-enhanced physics-informed neural networks for forward and inverse PDE problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2022, 393, 114823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, S.; Xie, H.; Xiong, F.; Yu, T.; Xiao, M.; Liu, L.; Yong, H. Discontinuity Computing Using Physics-Informed Neural Networks. J. Sci. Comput. 2023, 98, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toloubidokhti, M.; Ye, Y.; Missel, R.; Jiang, X.; Kumar, N.; Shrestha, R.; Wang, L. DATS: Difficulty-Aware Task Sampler for Meta-Learning Physics-Informed Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, R.H.; Lu, P.; Nocedal, J.; Zhu, C. A Limited Memory Algorithm for Bound Constrained Optimization. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 1995, 16, 1190–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sankaran, S.; Wang, H.; Perdikaris, P. An Expert’s Guide to Training Physics-informed Neural Networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.08468. [Google Scholar]

- Bengio, Y.; Louradour, J.; Collobert, R.; Weston, J. Curriculum learning. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–18 June 2009; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Meng, X.; Mao, Z.; Karniadakis, G.E. DeepXDE: A Deep Learning Library for Solving Differential Equations. SIAM Rev. 2021, 63, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, M.; Tan, Q.; Kartha, Y.; Lu, L. A comprehensive study of non-adaptive and residual-based adaptive sampling for physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 403, 115671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Wan, X.; Yang, C. DAS-PINNs: A deep adaptive sampling method for solving high-dimensional partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 476, 111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabian, M.A.; Gladstone, R.J.; Meidani, H. Efficient training of physics-informed neural networks via importance sampling. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 36, 962–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Wang, C. Active learning based sampling for high-dimensional nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 475, 111848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, A.; Bu, J.; Wang, S.; Perdikaris, P.; Karpatne, A. Rethinking the Importance of Sampling in Physics-Informed Neural Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02338. [Google Scholar]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR, Sardinia, Italy, 13–15 May 2010; Volume 9, pp. 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, T.A.; Hale, N.; Trefethen, L.N. (Eds.) Chebfun Guide; Pafnuty Publications: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Lu, L.; Song, S.; Huang, G. Learning Specialized Activation Functions for Physics-Informed Neural Networks. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2023, 34, 869–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Annavarapu, C.; Roy, P.; Sarma, K.A.K. Adaptive Interface-PINNs (AdaI-PINNs): An Efficient Physics-Informed Neural Networks Framework for Interface Problems. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2025, 37, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0.0075 | 0.0237 | 0.6451 | 0.6798 | 0.7229 | 0.7187 |

| CE-Vanilla | 0.0012 | 0.0076 | 0.0129 | 0.0151 | 0.0224 | 0.0244 |

| RAR-G | 0.0064 | 0.0087 | 0.0062 | 0.6678 | 0.6673 | 0.7518 |

| CE-RARG | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0036 | 0.0054 | 0.0077 | 0.0080 |

| CED-RARG | 0.0006 | 0.0014 | 0.0081 | 0.0057 | 0.0050 | 0.0046 |

| RAR-D | 0.0053 | 0.0121 | 0.0367 | 0.6451 | 0.6916 | 0.7126 |

| CE-RARD | 0.0010 | 0.0038 | 0.0165 | 0.0366 | 0.0374 | 0.0379 |

| CED-RARD | 0.0010 | 0.0031 | 0.0065 | 0.0098 | 0.0072 | 0.0082 |

| Method | Final Rel. L2 Error | Total Loops | Total Points Added | Training Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE-RARG | 0.0080 | 300 (fixed) | ∼7500 | 1.0× (baseline) |

| CED-RARG | 0.0046 | ∼500 (dynamic) | ∼12,500 | ∼1.3× |

| Method | |

|---|---|

| Vanilla | |

| CE-Vanilla | |

| RAR-G | |

| CE-RARG | |

| CED-RARG | |

| RAR-D | |

| CE-RARD | |

| CED-RARD |

| Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0.0004 | 0.0951 | 0.0394 | 0.3683 | 0.4198 | 0.5101 |

| CE-Vanilla | 0.0086 | 0.01666 | 0.0248 | 0.0369 | 0.0125 | 0.1578 |

| RAR-G | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0007 | 0.0012 | 0.0004 | 0.1048 |

| CE-RARG | 0.0002 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 0.0009 | 0.0018 | 0.0086 |

| CED-RARG | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 0.0011 | 0.0019 | 0.0045 |

| RAR-D | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0011 | 0.0004 | 0.1339 |

| CE-RARD | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0007 | 0.0011 | 0.0024 | 0.0078 |

| CED-RARD | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0008 | 0.0023 |

| Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0.0394 | 0.1516 | 0.1660 | 0.1652 | 0.3451 | 0.3173 |

| CE-Vanilla | 0.0097 | 0.0584 | 0.0768 | 0.2889 | 0.3356 | 0.3798 |

| RAR-G | 0.0004 | 0.0006 | 0.0089 | 0.0478 | 0.0809 | 0.1703 |

| CE-RARG | 0.0002 | 0.0044 | 0.0056 | 0.0096 | 0.0132 | 0.0603 |

| CED-RARG | 0.0003 | 0.0037 | 0.0119 | 0.0097 | 0.0257 | 0.0558 |

| RAR-D | 0.0003 | 0.0123 | 0.0090 | 0.0754 | 0.1443 | 0.1302 |

| CE-RARD | 0.0003 | 0.0026 | 0.0044 | 0.0068 | 0.0104 | 0.0447 |

| CED-RARD | 0.0002 | 0.0010 | 0.0021 | 0.0031 | 0.0050 | 0.0169 |

| Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0.0014 | 0.0028 | 0.0268 | 0.3192 | 0.7483 | 1.0589 |

| CE-Vanilla | 0.0008 | 0.0013 | 0.0020 | 0.0034 | 0.0061 | 0.3777 |

| RAR-G | 0.0008 | 0.0019 | 0.0029 | 0.0058 | 0.0447 | 0.4207 |

| CE-RARG | 0.0008 | 0.0011 | 0.0021 | 0.0025 | 0.0028 | 0.0081 |

| CED-RARG | 0.0008 | 0.0012 | 0.0018 | 0.0020 | 0.0022 | 0.0069 |

| RAR-D | 0.0017 | 0.0015 | 0.0027 | 0.0057 | 0.0146 | 0.3221 |

| CE-RARD | 0.0007 | 0.0012 | 0.0021 | 0.0024 | 0.0023 | 0.0064 |

| CED-RARD | 0.0006 | 0.0011 | 0.0016 | 0.0024 | 0.0023 | 0.0037 |

| Method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | 0.0069 | 0.0094 | 0.0122 | 0.0546 | 0.5692 | 0.8305 |

| CE-Vanilla | 0.0081 | 0.0071 | 0.0069 | 0.0071 | 0.0061 | 0.0054 |

| RAR-G | 0.0057 | 0.0271 | 0.0030 | 0.0040 | 0.5619 | 0.6232 |

| CE-RARG | 0.0044 | 0.0055 | 0.0040 | 0.0027 | 0.0029 | 0.0027 |

| CED-RARG | 0.0015 | 0.0047 | 0.0027 | 0.0031 | 0.0030 | 0.0025 |

| RAR-D | 0.0069 | 0.0086 | 0.0076 | 0.0044 | 0.6282 | 0.6474 |

| CE-RARD | 0.0062 | 0.0070 | 0.0073 | 0.0061 | 0.0040 | 0.0032 |

| CED-RARD | 0.0015 | 0.0068 | 0.0064 | 0.0040 | 0.0036 | 0.0030 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cetinkaya, H.; Ay, F.; Tunçel, M.; Nounou, H.; Nounou, M.N.; Kurban, H.; Serpedin, E. Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling for Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Robust Framework for Stiff PDEs. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243996

Cetinkaya H, Ay F, Tunçel M, Nounou H, Nounou MN, Kurban H, Serpedin E. Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling for Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Robust Framework for Stiff PDEs. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243996

Chicago/Turabian StyleCetinkaya, Hasan, Fahrettin Ay, Mehmet Tunçel, Hazem Nounou, Mohamed Numan Nounou, Hasan Kurban, and Erchin Serpedin. 2025. "Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling for Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Robust Framework for Stiff PDEs" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243996

APA StyleCetinkaya, H., Ay, F., Tunçel, M., Nounou, H., Nounou, M. N., Kurban, H., & Serpedin, E. (2025). Curriculum-Enhanced Adaptive Sampling for Physics-Informed Neural Networks: A Robust Framework for Stiff PDEs. Mathematics, 13(24), 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243996