Robust Explosion Point Location Detection via Multi–UAV Data Fusion: An Improved D–S Evidence Theory Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Innovatively constructing a lightweight evidence generation module. This module significantly reduces the computational complexity of fusion through an adaptive confidence allocation mechanism, while ensuring the stability of inference. It achieves efficient calibration and integration of multi–source conflicting evidence. Additionally, a multi–scale evidence perception unit is introduced to enhance the system’s ability to consistently describe the characteristics of heterogeneous sensor data and improve its anti–jamming performance.

- (2)

- Developing a confidence optimization module based on spatiotemporal correlation. By employing a serialized evidence accumulation strategy, a dynamic confidence update path is constructed. Compared to traditional static fusion methods, this approach performs better in explosion point testing, effectively capturing the continuity and correlation features of the explosion point location in the spatiotemporal domain.

- (3)

- Designing a hierarchical decision fusion architecture. The system utilizes weighted evidence synthesis and a learnable conflict allocation mechanism, balancing detection sensitivity and false alarm suppression needs through parameterized confidence propagation. This architecture deeply integrates observation data from different perspectives with spatial information, promoting multi–evidence complementarity and enhancing the continuity and robustness of explosion point localization in complex environments. Finally, a multi–objective optimization matching function is constructed, effectively addressing the imbalance and uncertainty challenges in explosion point matching within multi–UAV systems.

1.1. Mathematical Foundations and Theoretical Contributions

1.1.1. Fundamental Limitations of Classical D–S Theory

1.1.2. An Optimization–Theoretic Perspective

- Optimized Dynamic Weighting: We prove that our weight allocation rule emerges as the closed–form solution to a conflict minimization problem, providing decision–theoretic justification absent in prior work.

- Stable Conflict–Adaptive Fusion: We derive a fusion rule that automatically switches operational modes based on theoretically analyzed conflict thresholds, effectively acting as a mathematical regularizer against pathological fusion.

- Theoretical Guarantees: We provide a priori theoretical guarantees on system performance, formally proving conflict attenuation and robustness properties.

- Unified Mathematical Framework: Our approach unifies evidence fusion under a minimax optimization principle, minimizing the maximum potential risk from evidence conflict.

1.2. Recent Advances and Comparative Analysis of Dynamic Evidence Fusion Methods

1.2.1. Evolution of High–Conflict Evidence Processing Mechanisms

1.2.2. Innovations in Computational Efficiency and Scalability

1.2.3. The Unique Contribution of This Paper

2. Multi–UAV Explosion Point Location Testing Method and Improved D–S Evidence Algorithm

2.1. Overall Framework

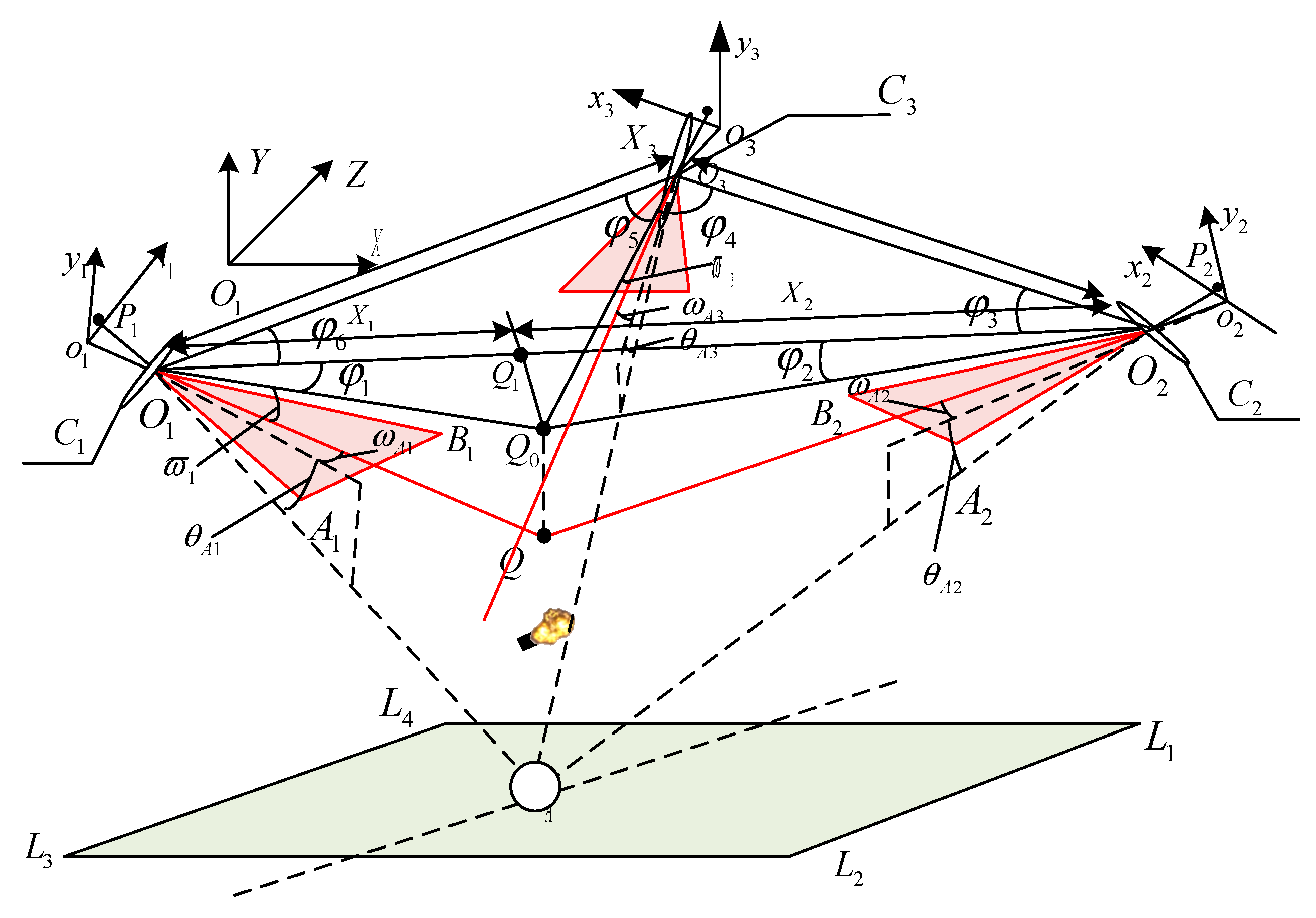

2.2. Multi–View Vision–Based Projectile Burst Point Inversion Calculation Model

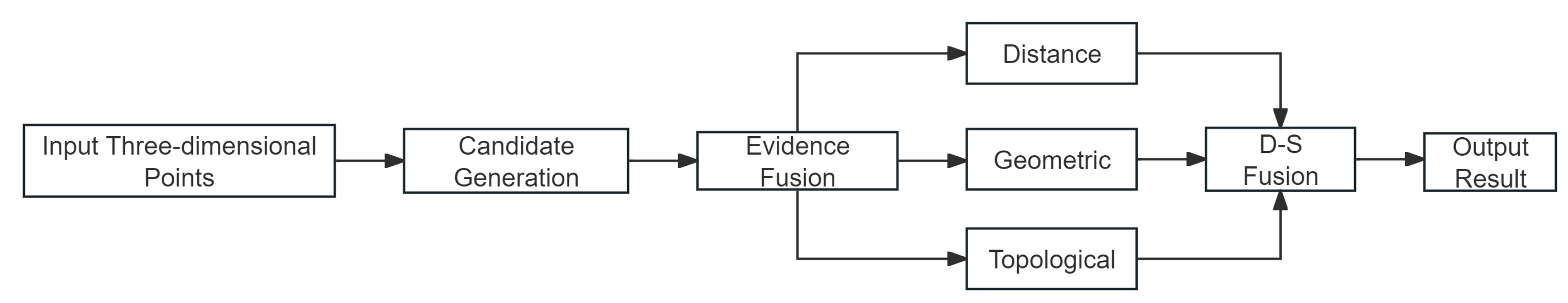

2.3. The Three–Dimensional Data Point Matching Algorithm Based on Multi–Evidence Fusion

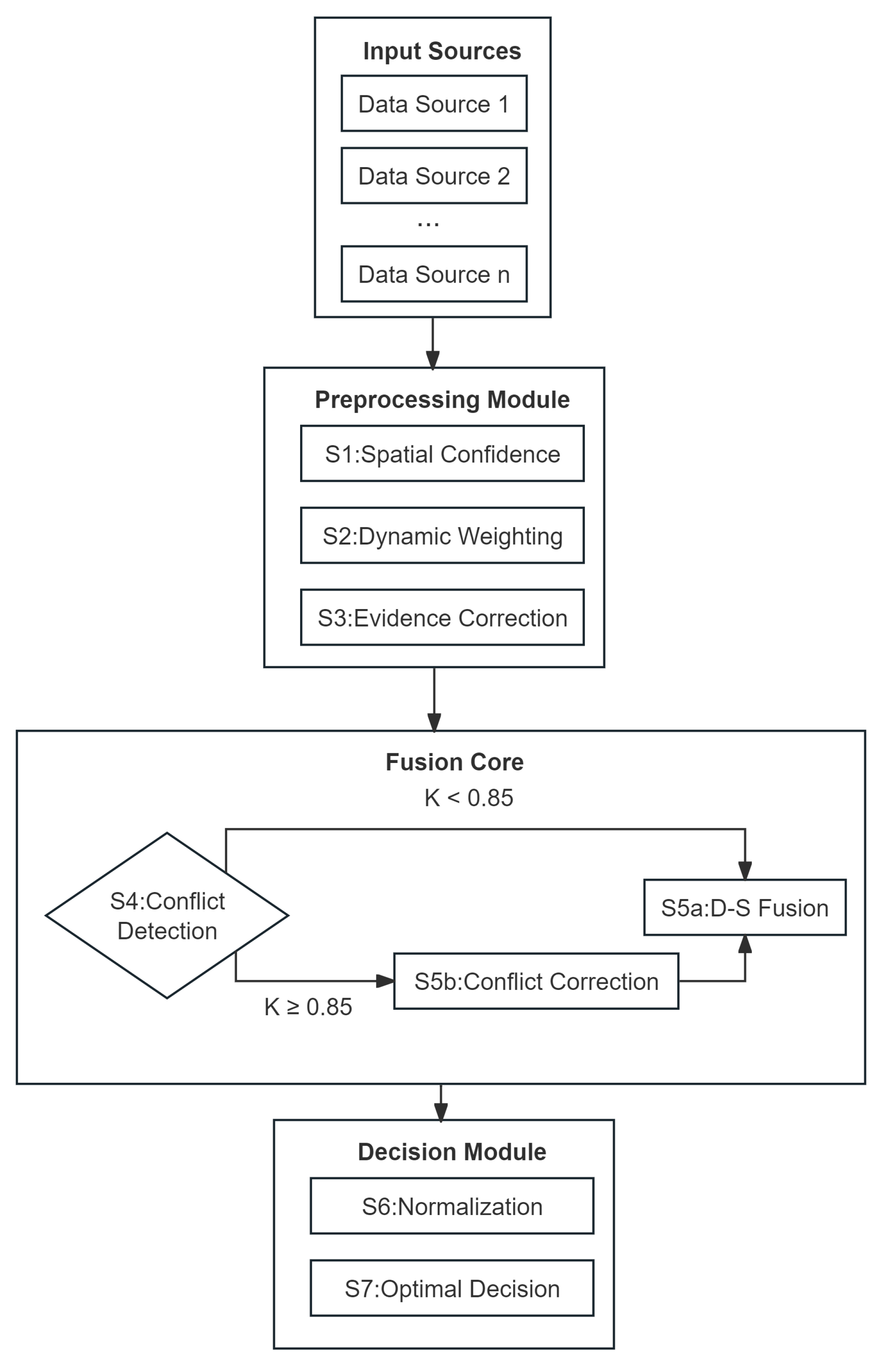

2.4. Improved D–S Evidence Theory Algorithm

3. Experimental Analysis

3.1. Experimental Setup

Scenario Generation Methodology

3.2. Three–Dimensional Data Matching with Multiple Evidence Fusion

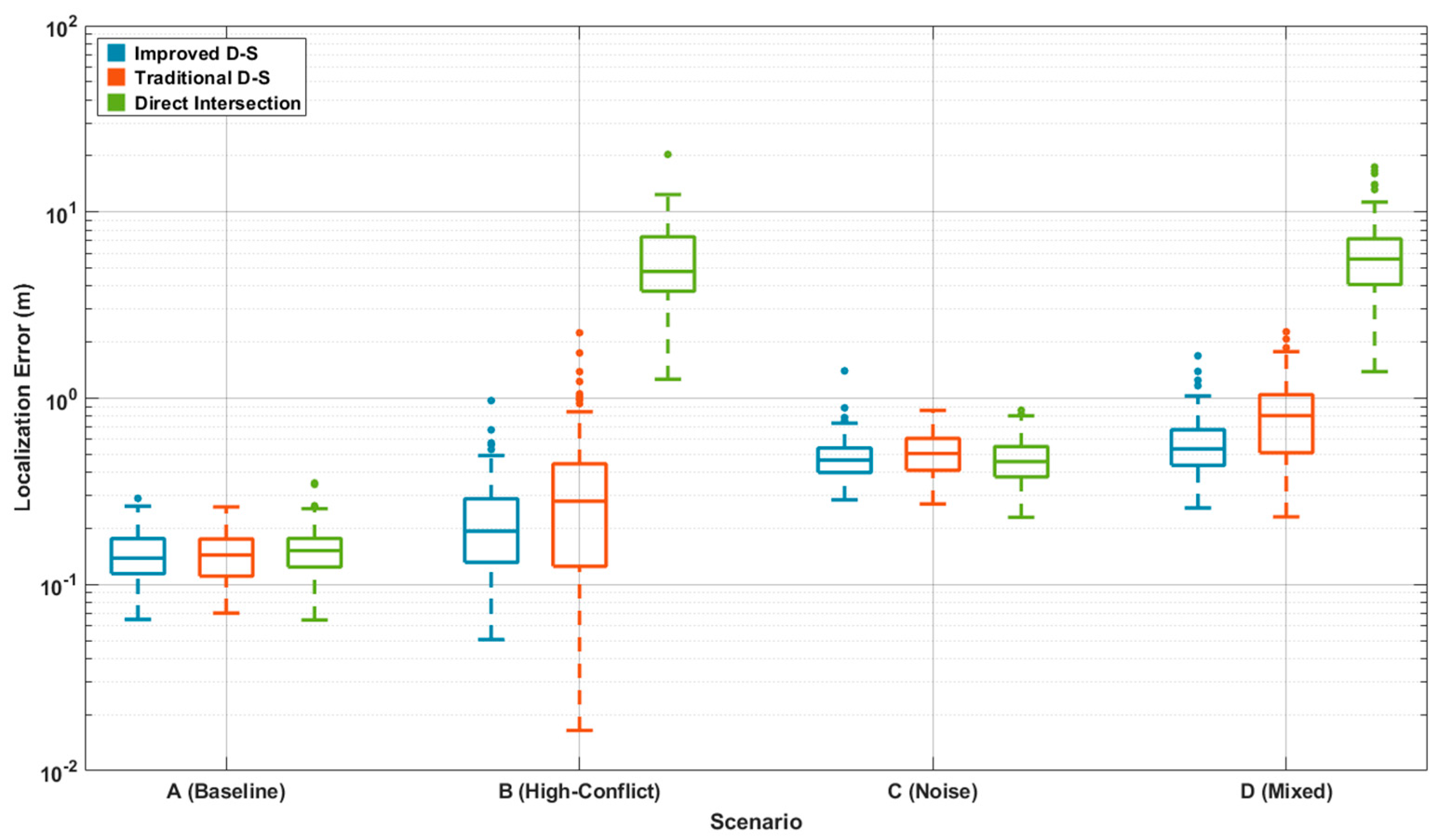

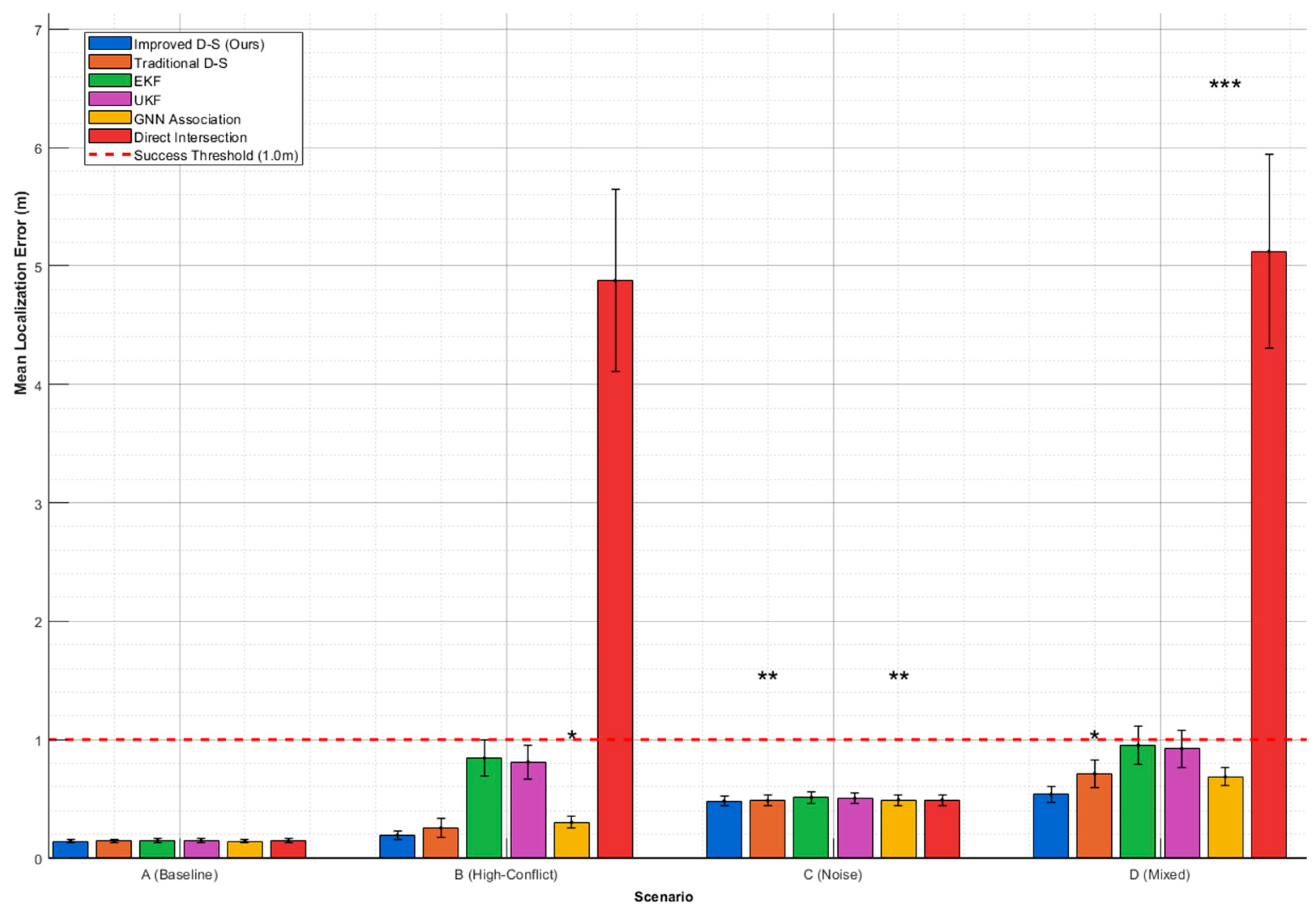

3.3. Comparative Experiments

3.4. Ablation Study with Mathematical Interpretation

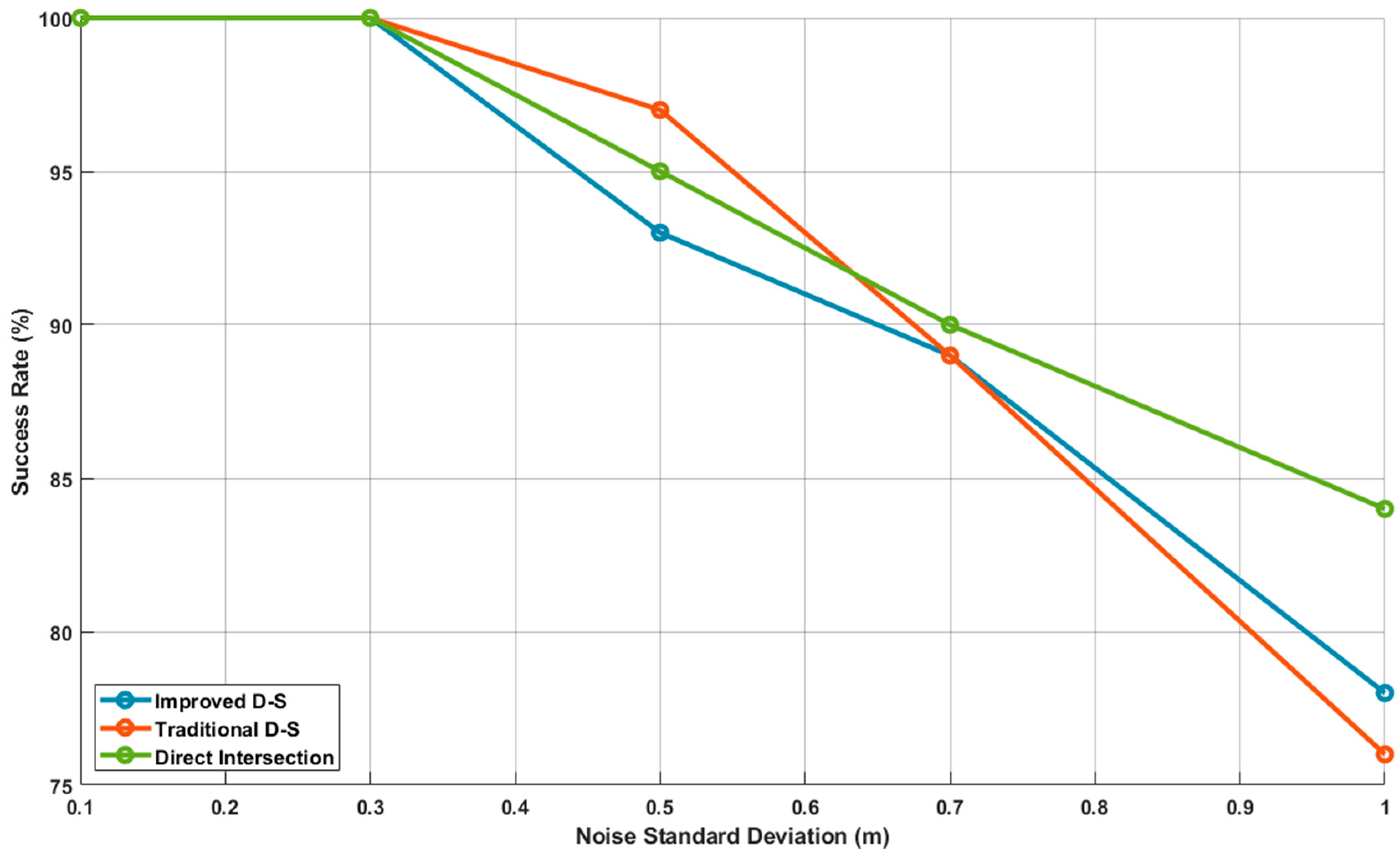

3.5. Parameter Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

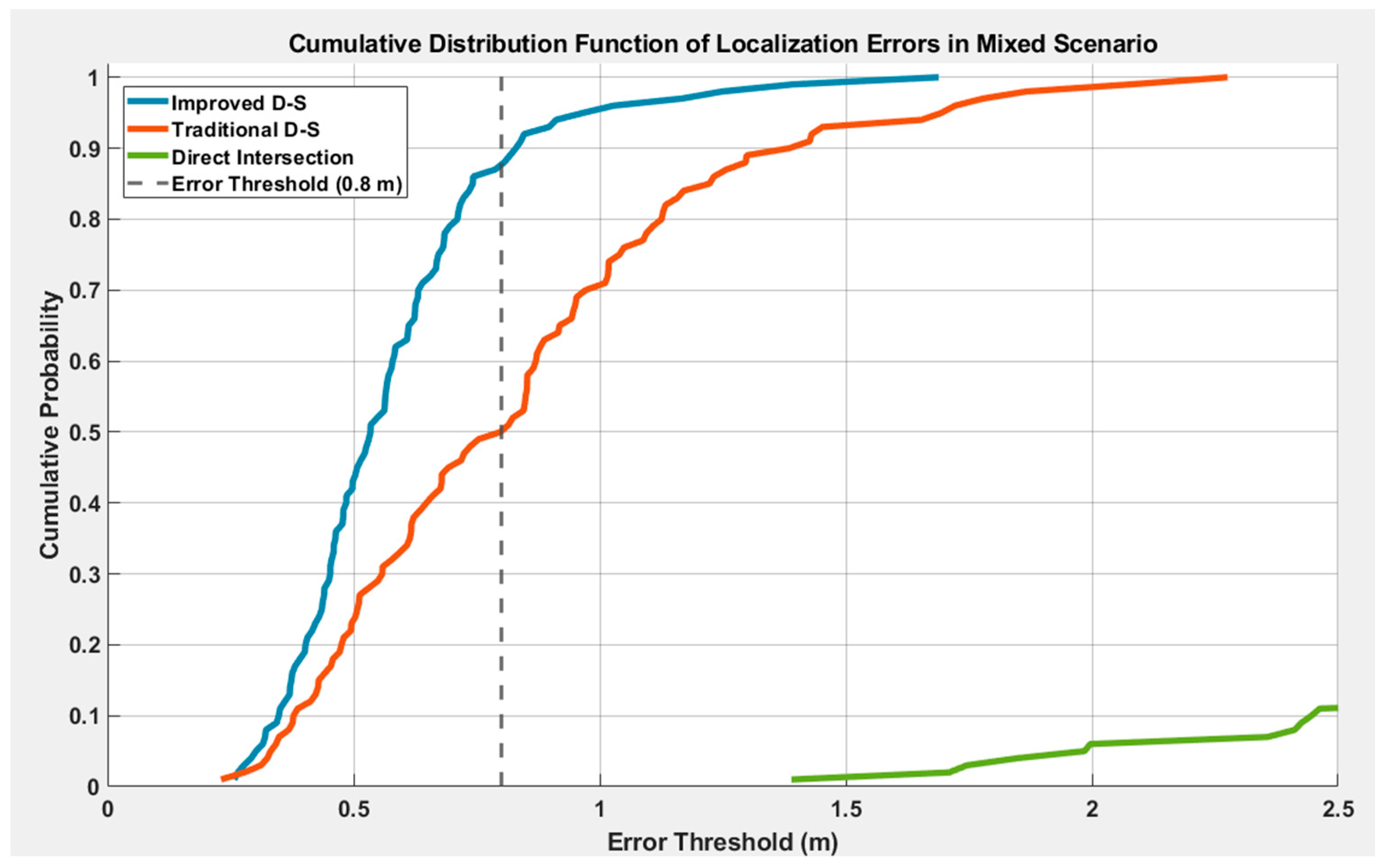

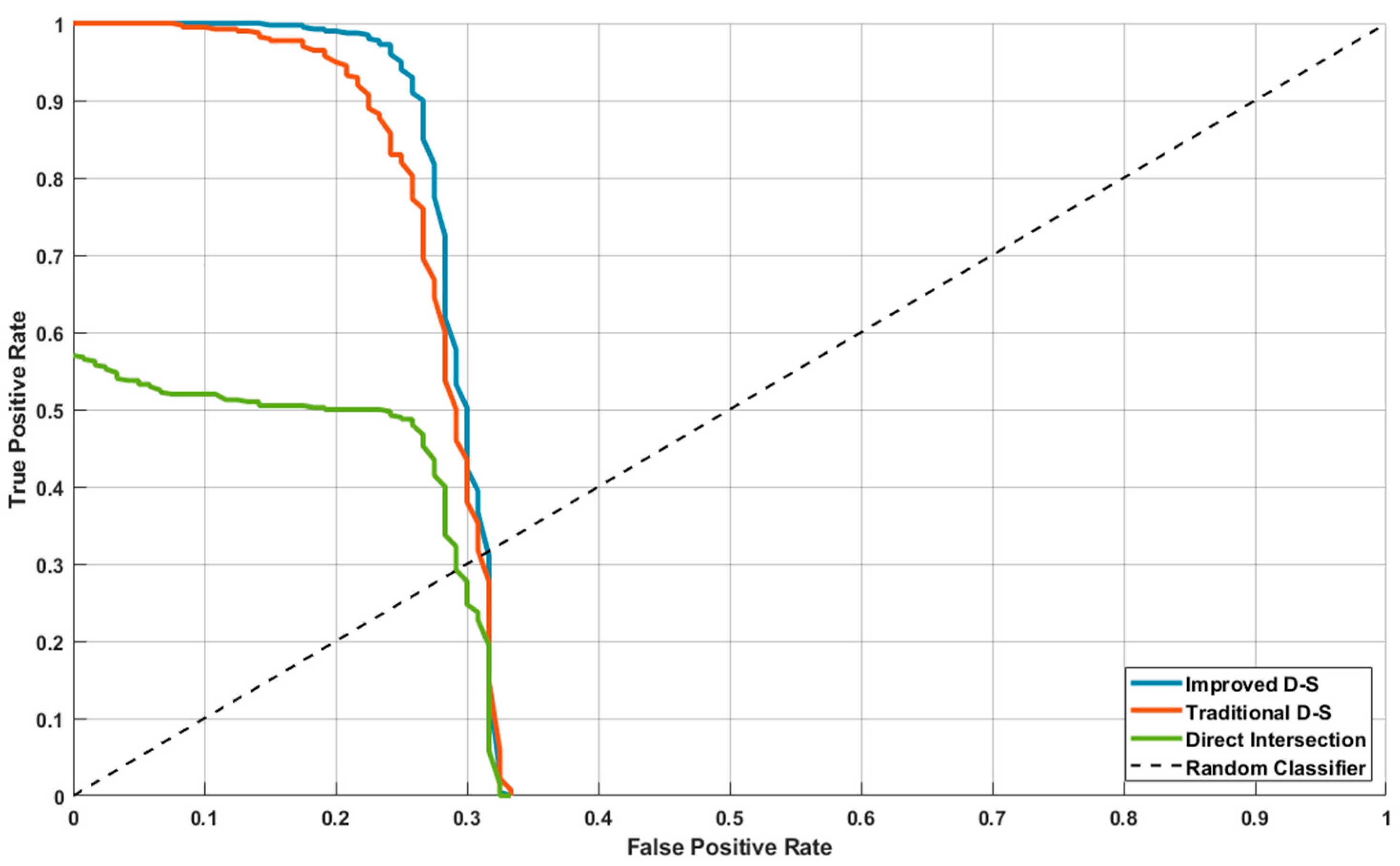

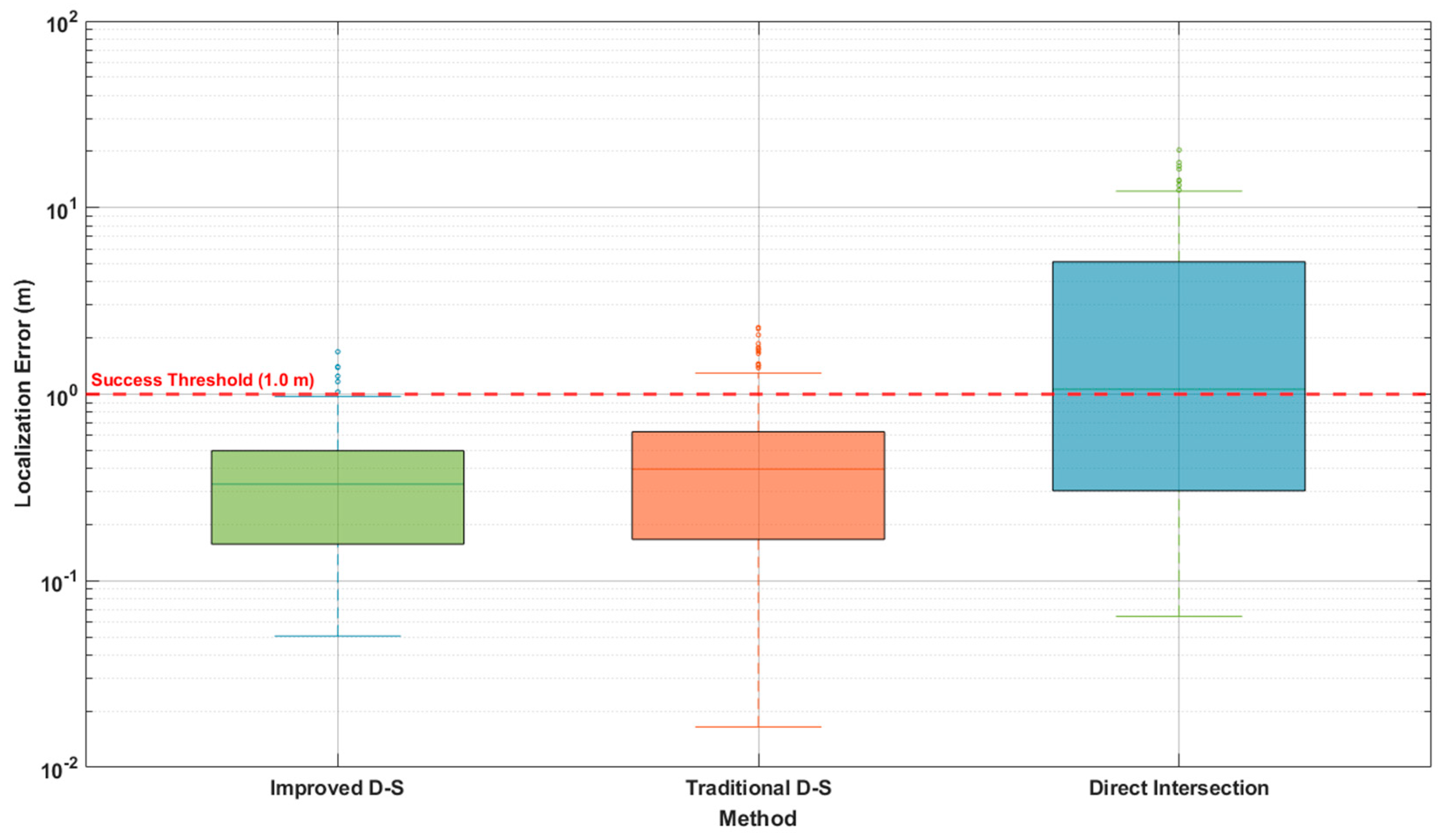

3.6. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation

3.7. Statistical Significance Analysis

4. Theoretical Framework and Mathematical Analysis

4.1. Preliminaries and Mathematical Foundations

4.2. Dynamic Weighting as Asymmetry–Robust Optimization

4.3. Theoretical Guarantees of the Improved Framework

4.4. Axiomatic Analysis of the Proposed Fusion Rule

5. Conclusions

- The introduction of dynamic basic probability assignment and conflict–adaptive reallocation mechanisms enhances the system’s ability to quantify uncertain information. These mechanisms effectively distinguish explosion point features from different sensor sources and suppress high–conflict evidence caused by environmental interference, meeting the dual demands for real–time performance and robustness in complex battlefield environments.

- The use of temporal evidence accumulation and spatial correlation verification strategies effectively overcomes the issue of missed detections and trajectory breakage, which traditional methods face when targets appear briefly or are partially occluded. Combined with multi–scale confidence weighting and decision–level fusion, the system’s perception consistency of the explosion point’s spatiotemporal location is enhanced, improving both the continuity of localization and stable output under strong interference.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, L.; Shan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, X. Damage Identification of Composite Material Structures Based on Strain Response and DS Evidence Theory. Noise Vib. Control 2025, 45, 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Song, C.; Wu, X. Gearbox fault diagnosis method based on multi–sensor data fusion and GAN. J. Mech. Strength 2025, 47, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Cheng, H. Deep learning ensemble streamflow prediction based on explainable multi–source data feature fusion. Adv. Water Sci. 2025, 36, 581–595. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, H.; Wei, J.; Song, Z. Welding Quality Monitoring Based on Multi–Source Data Fusion Technology. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 2025, 45, 471–481. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Yu, Z. Multi–layer Perceptron Interactive Fusion Method for Infrared and Visible Images. Infrared Technol. 2025, 47, 619–627. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Mei, Y.; Niu, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Huo, M.; Fan, Y.; Luo, D.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Review of technological hotspots of unmanned aerial vehicle in 2024. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2025, 43, 143–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cherif, B.; Ghazzai, H.; Alsharoa, A. Lidar from the sky: UAV integration and fusion techniques for advanced traffic monitoring. IEEE Syst. J. 2024, 18, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Adhikari, D.; Khan, H.; Ahmad, S.; Esposito, C.; Choi, C. Optimizing mobile robot localization: Drones–enhanced sensor fusion with innovative wireless communication. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2024–IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20 May 2024; IEEE: Tokyo, Japan, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.F.; Chen, X.; Li, H.W.; Liu, T.; Chen, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, Y. Airborne small target detection method based on multimodal and adaptive feature fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5637215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.J.; Yuan, B.X.; Du, J.W.; Chen, B.; Xie, H.; Tian, J.; Yuan, Z. MFFSODNet: Multiscale feature fusion small object detection network for UAV aerial images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5015214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.D.; He, Z.W.; Yang, Y.X.; Nie, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, M. MSF–SLAM: Multisensor–fusion–based simultaneous localization and mapping for complex dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 19699–19713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Lu, Y.; Ruan, L. Joint optimization control algorithm for passive multi–sensors on drones for multi–target tracking. Drones 2024, 8, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Mi, J.-S.; Zhang, S.-P.; Zhang, X. Fused decision rules of multi–intuitionistic fuzzy information systems based on the DS evidence theory and three–way decisions. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 27, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Lei, H. Dual data fusion fault diagnosis of transmission system based on entropy weighted multi–representation DS evidence theory and GCN. Measurement 2024, 243, 116308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Ning, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Q.; Wang, Q. An improved DS evidence fusion algorithm for sub–area collaborative guided wave damage monitoring of large–scale structures. Ultrasonics 2025, 152, 107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Intelligent evaluation of coal mine solid filling effect using fuzzy logic and improved DS evidence theory. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Tang, L.; Huang, M.; Wu, Y. Integrating D–S evidence theory and multiple deep learning frameworks for time series prediction of air quality. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Pan, X.; Jiang, F.; Guan, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, P. Novel rolling bearing state classification method based on probabilistic Jensen–Shannon divergence and decision fusion. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pei, J. Aerial Target Detection Algorithm Fused with Multi–scale Features. J. Syst. Simul. 2025, 37, 1486. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Gou, Y.; Lei, T.; Jin, L.; Song, Y. Small object detection based on multi–scale feature fusion using remote sensing images. Opto–Electron. Eng. 2022, 49, 210363. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, N.; Wang, C. Infrared Small Target Detection with Mixed–Frequency Feature Fusion Detection Model. Infrared Technol. 2025, 47, 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Z.; Luo, S. Object Detection Method in Complex Traffic Scenarios. Inf. Control 2025, 54, 632–643. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, X.; Jia, B.; Chen, D. An Improved YOLOv11–Based Target Detection Method for Underwater Hull–Cleaning Robots. Ship Boat 2025, 36, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, A. Rethinking Adaptive Contextual Information and Multi-Scale Feature Fusion for Small-Object Detection in UAV Imagery. Sensors 2025, 25, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Xie, J. A Markov Transferable Reliability Model for Attack Prediction. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2025, 42, 348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Sun, H.; He, Z.; Zhang, J. Fault Diagnosis with SVM and Improved AHP–DS Evidence Fusion. Navig. China 2025, 44, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Kong, L.; Yu, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, R. Development and Application of 3D Reconstruction Technology at Different Scales in Plant Research. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2025, 60, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Tang, H. Multi–objective topology optimization design of truss structures based on evidence theory under limited information. Xibei Gongye Daxue Xuebao/J. Northwest. Polytech. Univ. 2023, 41, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X. Ship Fire Prediction Method Based on Evidence Theory with Fuzzy Reward. J. Syst. Simul. 2025, 37, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y. An Approach to Identifying Emerging Technologies by Fusing Multi–Source Data. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2025, 42, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. Hashing for localization: A review of recent advances and future trends. Exp. Technol. Manag. 2025, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, X. Risk mining and location analysis of coal mine equipment control failures based on the Apriori Algorithm. China Min. Mag. 2025, 34, 216–220. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Gao, B.; Gao, D. Quantification method for uncertainty in deep–sea acoustic channels. ACTA Acust. 2025, 50, 778–787. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhao, J.; Ai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L. A safe and energy–efficient obstacle avoidance method for UAVs. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2025, 47, 1658. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, P.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Adaptive Federated Bucketized Decision Tree Algorithm for Industrial Digital Twins. J. Henan Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2025, 46, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Guan, X. Evidential reasoning–based decision method for track association verification. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2025, 47, 2819. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Han, X. Research on pose measurement between two non–cooperative spacecrafts in close range based on concentric circles. Opto–Electron. Eng. 2018, 45, 180126. [Google Scholar]

| Method Category | Core Mechanism | Main Advantages | Typical Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Analysis Combination Rule (AGC) | One–time analytical computation, non–iterative fusion | Supports weight and reliability parameters, handles local unknown information | Complex network analysis, multi–criteria decision–making | Sensitive to prior parameters, weak adaptability in nonlinear scenarios |

| Hybrid D–S Rule | Induced ordered weighted average operator + adaptive weights | 34.1% accuracy improvement in high–conflict scenarios | Subway traction motor bearing fault diagnosis | Computational complexity increases with evidence quantity |

| Dynamic Evidence Fusion Neural Network | Integration of uncertainty theory and neural networks | Handles uncertainty in dynamic functional connections | Handles uncertainty in dynamic functional connections | Requires large amounts of training data |

| Data–driven Fusion Selection Paradigm | Critical threshold calculation based on sample size and feature dimensions | Reduces method selection cost, optimizes fusion strategies | Multimodal medical data fusion | Relies on generalized linear model assumptions |

| Machine Learning–driven Fusion | Low–level data fusion and principal component analysis | Real–time integration of portable sensor data | Forensic chemical analysis, environmental monitoring | High requirements for sensor calibration |

| UAV | Position Coordinates (x, y, z) (m) | Camera System | Lens FOV | Resolution | Focus (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | (0, 0, 100) | OAK–4P–New | 140° × 110° | 1280 × 800 | 2.1 |

| B | (−150, 150, 100) | OAK–4P–New | 140° × 110° | 1280 × 800 | 2.1 |

| C | (150, −150, 100) | OAK–4P–New | 140° × 110° | 1280 × 800 | 2.1 |

| Parameter Category | Scenario A | Scenario B | Scenario C | Scenario D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position Noise | N (0, 0.1) | N (0, 0.1) + bias | Multi–modal | Dynamic multi–modal |

| Conflict Coefficient | <0.3 | 0.7–0.95 | <0.4 | 0.6–0.95 |

| Temporal Asynchrony | None | 50–100 ms | None | Random 50–150 ms |

| Data Integrity | 100% | 100% | 95% | 90% |

| Dual UAVs | Spatial Coordinates of Suspected Bullet Impact Point (m) |

|---|---|

| AB | (38.478, −23.748, −13.304); (31.159, −10.303, −14.258); (64.385, −21.858, −3.504); (66.248, −0.585, −20.594) |

| AC | (24.897, −9.478, 13.219); (38.797, −23.657, −13.442); (33.523, −0.764, −7.557); (64.670, −22.252, −2.980) |

| BC | (63.621, −6.336, −24.934); (39.163, −23.892, −13.018); (64.128, −21.968, −3.025); (32.392, −6.215, 3.361) |

| Source of Blast Points | Coordinate (x, y, z) | Type |

|---|---|---|

| AB intersection | (38.478, −23.748, −13.304) | Real blast points |

| AB intersection | (31.159, −10.303, −14.258) | False blast points |

| AB intersection | (64.385, −21.858, −3.504) | Real blast points |

| AB intersection | (66.248, −0.585, −20.594) | False blast points |

| AC intersection | (24.897, −9.478, 13.219) | False blast points |

| AC intersection | (38.797, −23.657, −13.442) | Real blast points |

| AC intersection | (33.523, −0.764, −7.557) | False blast points |

| AC intersection | (64.670, −22.252, −2.980) | Real blast points |

| BC intersection | (63.621, −6.336, −24.934) | False blast points |

| BC intersection | (39.163, −23.892, −13.018) | Real blast points |

| BC intersection | (64.128, −21.968, −3.025) | Real blast points |

| BC intersection | (32.392, −6.215, 3.361) | False blast points |

| Point Location | Original Confidence_Real | Original Confidence_False | Weight Factor_AB | Weight Factor_AC | Weight Factor_BC | New Confidence_Real | Fused Confidence_Real | Fused Confidence_False |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.32 |

| P2 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.88 |

| P3 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| P4 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| P5 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| P6 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| P7 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| P8 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| P9 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| P10 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| P11 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.34 |

| P12 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.90 |

| Method | A (Baseline) | B (High–Conflict) | C (Noise) | D (Mixed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved D–S (Ours) | 0.141 | 0.192 | 0.482 | 0.538 |

| Traditional D–S | 0.143 | 0.254 | 0.485 | 0.712 |

| EKF | 0.148 | 0.845 | 0.510 | 0.951 |

| UKF | 0.146 | 0.812 | 0.505 | 0.923 |

| GNN Association | 0.142 | 0.301 | 0.490 | 0.685 |

| Direct Intersection | 0.145 | 4.876 | 0.491 | 5.124 |

| Model | Components Active | A (Baseline) | B (High–Conflict) | C (Noise) | D (Mixed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model (Ours, Δ = ±0.2) | DW + CC | 0.141 | 0.192 | 0.482 | 0.538 |

| Full Model (Δ = ±0.1) | DW + CC | 0.142 | 0.201 | 0.485 | 0.545 |

| Full Model (Δ = ±0.3) | DW + CC | 0.141 | 0.208 | 0.490 | 0.552 |

| w/o Type Correction (Δ = 0) | DW + CC | 0.142 | 0.225 | 0.495 | 0.568 |

| w/o Dynamic Weight (DW) | CC only | 0.180 | 0.547 | 0.598 | 0.845 |

| w/o Conflict Correction (CC) | DW only | 0.145 | 4.876 | 0.525 | 4.901 |

| Traditional D–S | Neither | 0.143 | 4.901 | 0.485 | 0.712 |

| Method | Scenario | Precision | Recall | F1–Score | Comp. Time (ms) | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved D–S (Ours) | B (High–Conflict) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 12.5 | 80 |

| Traditional D–S | B (High–Conflict) | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 8.2 | 122 |

| EKF | B (High–Conflict) | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 5.1 | 196 |

| UKF | B (High–Conflict) | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 5.3 | 189 |

| Improved D–S (Ours) | D (Mixed) | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 12.8 | 78 |

| Traditional D–S | D (Mixed) | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 8.2 | 122 |

| Method | Underlying Principle | Commutativity | Associativity | m(∅) After Fusion | Handling High Conflict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our Method | Minimax Optimization | Yes | Conditional Yes | 0 | Adaptive Regularization |

| Classical D–S | Bayesian Extension | yes | yes | 0 | Catastrophic Failure |

| Yager’s Rule | Belief Discounting | yes | No | ≥0 | Discounting to Ignorance |

| Murphy’s Method | Averaging Principle | yes | yes | 0 | Averaging Effect |

| Deng et al. | Distance Measure | yes | No | 0 | Probabilistic Transformation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Li, H. Robust Explosion Point Location Detection via Multi–UAV Data Fusion: An Improved D–S Evidence Theory Framework. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243997

Liu X, Li H. Robust Explosion Point Location Detection via Multi–UAV Data Fusion: An Improved D–S Evidence Theory Framework. Mathematics. 2025; 13(24):3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243997

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xuebin, and Hanshan Li. 2025. "Robust Explosion Point Location Detection via Multi–UAV Data Fusion: An Improved D–S Evidence Theory Framework" Mathematics 13, no. 24: 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243997

APA StyleLiu, X., & Li, H. (2025). Robust Explosion Point Location Detection via Multi–UAV Data Fusion: An Improved D–S Evidence Theory Framework. Mathematics, 13(24), 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13243997