1. Introduction

Agarwood (

Aquilaria spp.), a valuable tree species indigenous to Southeast Asia, produces a resin highly esteemed as the “gold of plants,” occupying a unique and indispensable role in medicine, culture, and the economy. The formation of agarwood resin occurs when the tree undergoes natural injury or microbial infection, which induces the secretion of aromatic resin as part of its self-repair mechanism [

1,

2]. This distinctive biological phenomenon renders agarwood an exceptionally rare natural resource. In traditional medicinal practices, agarwood is recognized for its therapeutic properties, including the promotion of qi circulation, analgesic effects, warming of the middle burner to alleviate vomiting, and the regulation of respiration to relieve asthma. It continues to be extensively incorporated into contemporary Chinese medicinal formulations [

3]. From a cultural perspective, agarwood holds significant value in religious rituals and among scholars and literati, embodying a rich heritage of historical and cultural significance spanning millennia [

4]. Economically, high-quality agarwood commands prices reaching several hundred dollars per gram, exceeding the value of gold, and has fostered the development of a comprehensive industrial supply chain [

5]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the value of agarwood spans multiple dimensions: from medicinal tea and cultural incense to high-value accessories like bracelets carved from the precious wood itself.

Nevertheless, the sustainable utilization of this precious resource is confronted with substantial challenges. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has classified wild agarwood populations as vulnerable, citing overexploitation as a primary cause of their near depletion [

4]. In response, artificial cultivation has emerged as the sole viable strategy to sustain industry growth. However, intensive cultivation practices are impeded by significant threats from pests and diseases [

6]. Notably, foliar herbivorous pests, which directly impair photosynthesis and hinder tree growth, represent a critical constraint on the healthy advancement of the agarwood industry.

The advancement of pest monitoring technology is fundamentally linked to the progression of smart agriculture and can be broadly categorized into three developmental phases. Initially, pest monitoring was conducted exclusively through manual field inspections. This method was characterized by inefficiency and high labor demands, relying heavily on the subjective expertise of individual inspectors, which often resulted in considerable delays and variability. In extensive agricultural plantations, a comprehensive inspection cycle could span several weeks. This delay increases the risk of missing critical intervention periods for pest and disease management. Consequently, irreversible economic damage may occur. To address the shortcomings of manual inspection, researchers adopted traditional machine learning techniques. These approaches typically utilized handcrafted features—such as color, texture, and shape—paired with classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and random forests for pest identification [

7,

8,

9,

10]. While this strategy introduced a degree of automation, its effectiveness was constrained by the quality of feature engineering. The inherent morphological variability of pests, the complexity of background interference, and fluctuating lighting conditions in practical environments significantly limited the generalizability and robustness of these methods.

In recent years, deep learning-based detection models, particularly those utilizing convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures, have achieved significant advancements in agricultural pest detection due to their robust end-to-end feature learning capabilities. Notable examples of such architectures include Faster R-CNN [

11], SSD [

12], and the YOLO series [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Yang et al. proposed the Maize-YOLO model [

18], an enhanced version of YOLOv7 that substantially reduces computational complexity while improving the accuracy of rice pest detection by integrating the CSPResNeXt-50 module with the VOV-GSCSP module. Similarly, Wang and colleagues developed the RGC-YOLO model [

19], which replaces conventional convolutional layers with the GhostConv structure and incorporates a hybrid attention mechanism, facilitating efficient multi-scale recognition of rice diseases and pests. Furthermore, Liu et al. introduced YOLO-Wheat for wheat pest detection [

20]; Guan et al. devised a multi-scale pest detection approach termed GC-Faster R-CNN by integrating hybrid attention mechanisms [

21]; Yu et al. presented LP-YOLO [

22], a lightweight pest detection method; and Tang et al. proposed SP-YOLO for multi-scale pest detection in beet fields [

23]. Collectively, these studies underscore the substantial application potential and continuous innovative progress of CNN-based models in the domain of agricultural pest detection. CNN models exhibit inherent limitations. Their primary advancements have predominantly targeted the efficiency of convolutional operations and the enhancement of local feature extraction, yet they do not fundamentally address the constraints imposed by the limited local receptive fields characteristic of CNNs. This intrinsic property imposes a natural bottleneck on the model’s ability to comprehend the global context within images.

To transcend these locality restrictions, researchers have increasingly incorporated the Transformer architecture into computer vision tasks [

24]. The core self-attention mechanism of Transformers facilitates direct computation of interactions across all regions of an image, thereby enabling effective modeling of global contextual information. In the domain of agricultural pest detection, Transformers have shown promise in capturing complex scene relationships and global context, resulting in significant improvements in detection performance [

25,

26,

27]. Nonetheless, this enhanced global modeling capability incurs a quadratic increase in computational complexity. Consequently, the demand for computational resources is substantially elevated. Consequently, this limitation poses significant challenges for deploying such models in agricultural field settings, where processing high-resolution images efficiently is essential. In this context, a novel approach to sequence modeling—the state space models (SSMs) [

28,

29] and, more specifically, the selective state space model exemplified by Mamba—has garnered considerable interest owing to its distinctive advantages in handling long sequences [

30]. By leveraging a selective state mechanism, SSMs are capable of efficiently capturing global contextual information akin to Transformers while maintaining linear computational complexity. This results in a substantial enhancement in computational efficiency without sacrificing performance. Therefore, State Space Models (SSMs) are particularly suitable for agricultural pest detection. In complex field images, understanding the global scene context (such as leaf distribution, presence of shadows, or pest infestation patterns) is crucial for accurately locating small and blurry targets. SSMs provide an efficient mechanism to achieve this global understanding, which standard Transformer models struggle with due to their excessive computational demands, while CNNs are fundamentally limited by their local receptive fields. Conceptually, SSMs can be seen as a bridge between CNNs and Transformers: they retain the core of efficient recurrent sequence processing (similar to the inductive bias of CNN’s local processing) while achieving a global receptive field and data-dependent feature selection capability comparable to Transformer’s self-attention mechanism.

Table 1 provides a comparative summary of these three architectural paradigms.

Consequently, SSMs emerge as a promising solution to the inherent trade-off between the locality constraints of CNNs and the computational demands of Transformers. Notably, SSM-based models have been employed in agricultural pest classification; for instance, Wang et al. introduced InsectMamba [

31], representing the inaugural application of an SSM framework to pest classification, thereby enabling the model to extract comprehensive visual features for accurate pest identification.

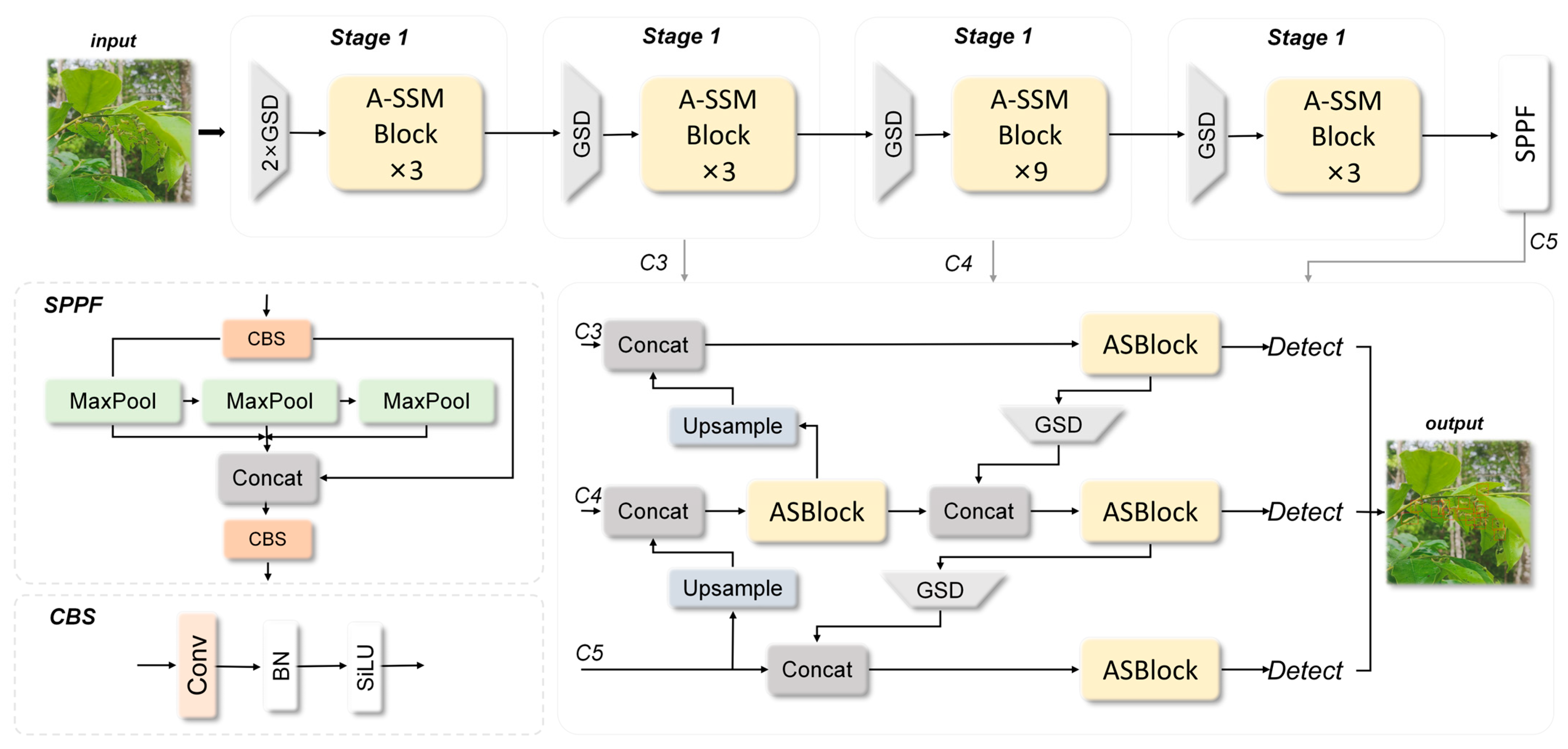

Despite significant progress in the domain of agarwood pest detection, critical research gaps persist. While state space models have exhibited exceptional proficiency in sequence modeling, their utilization has predominantly been confined to classification tasks. The exploration of their potential in dense object detection remains limited, particularly within agricultural contexts that demand precise localization and multi-scale recognition, such as the complex environments associated with agarwood pest detection. To address these challenges, an innovative detection framework called the Adaptive State Space Convolution Fusion Network (ASCNet) is introduced in this study, as an innovative detection framework that synergistically combines the complementary advantages of convolutional operations and state space modeling. This integration is realized through three principal contributions:

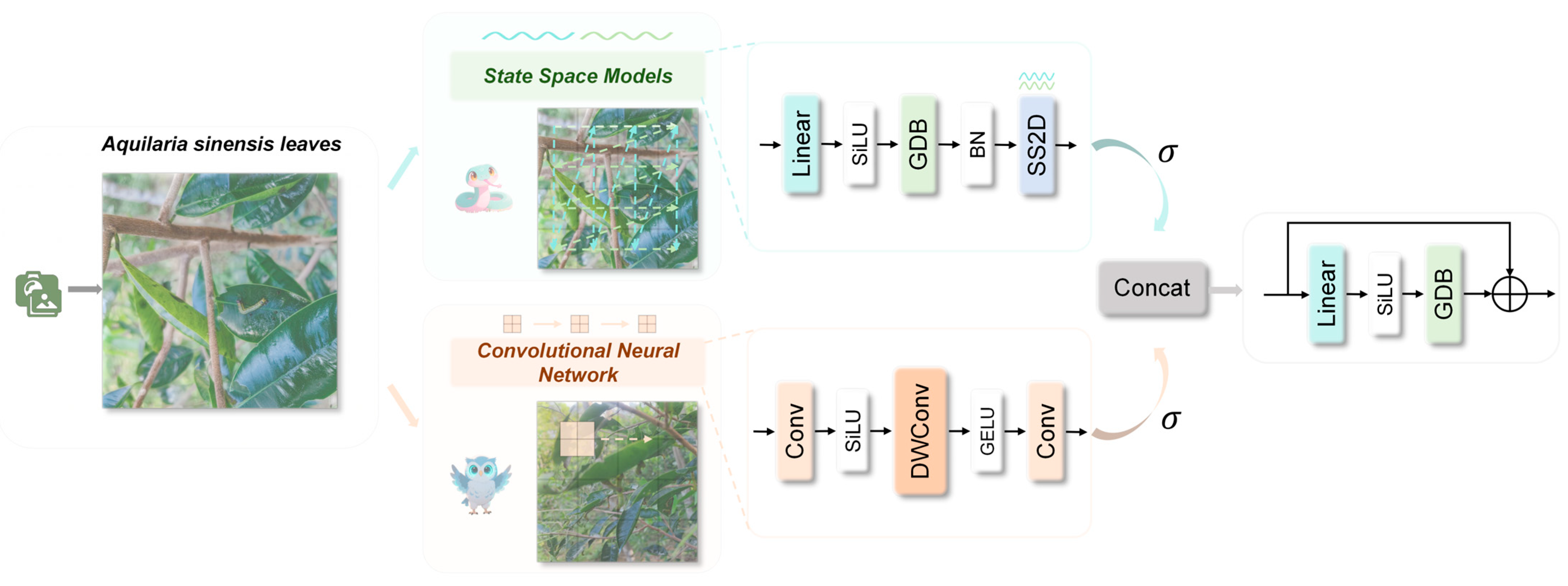

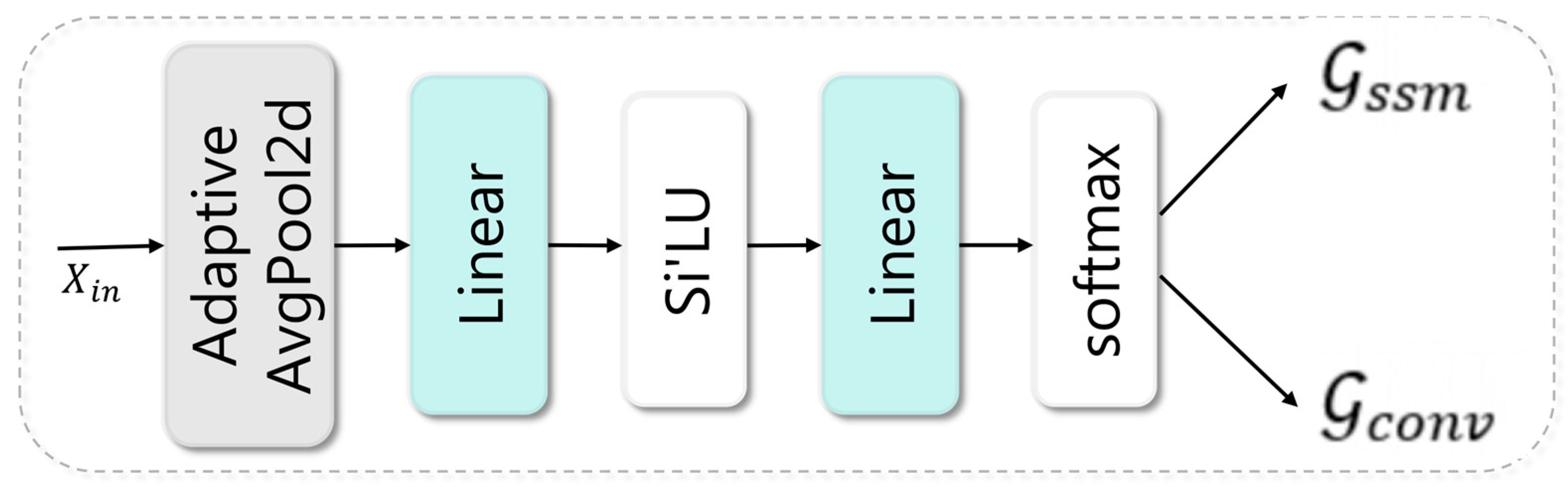

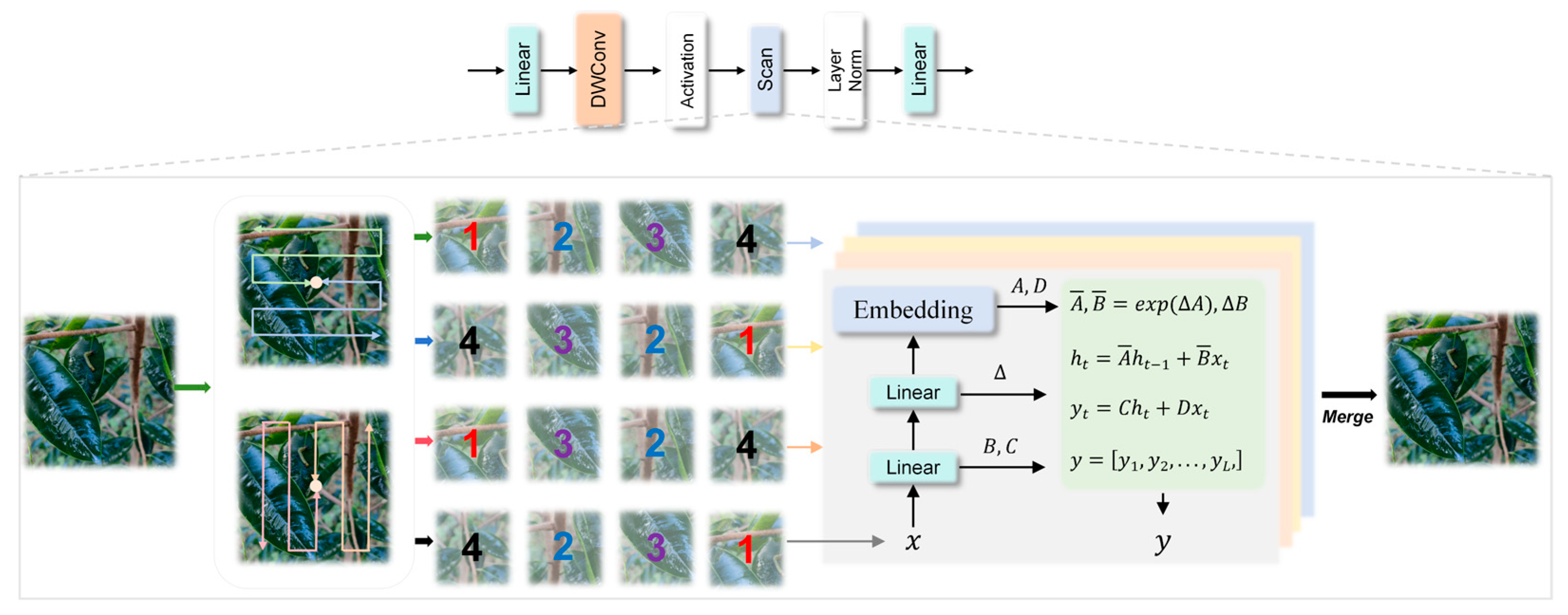

A dual-path adaptive fusion mechanism, implemented in the Adaptive State Space Convolution Fusion Module (ASBlock). This module processes features from the state-space model and convolutional pathways in parallel, employing a gating mechanism to dynamically adjust their contributions.

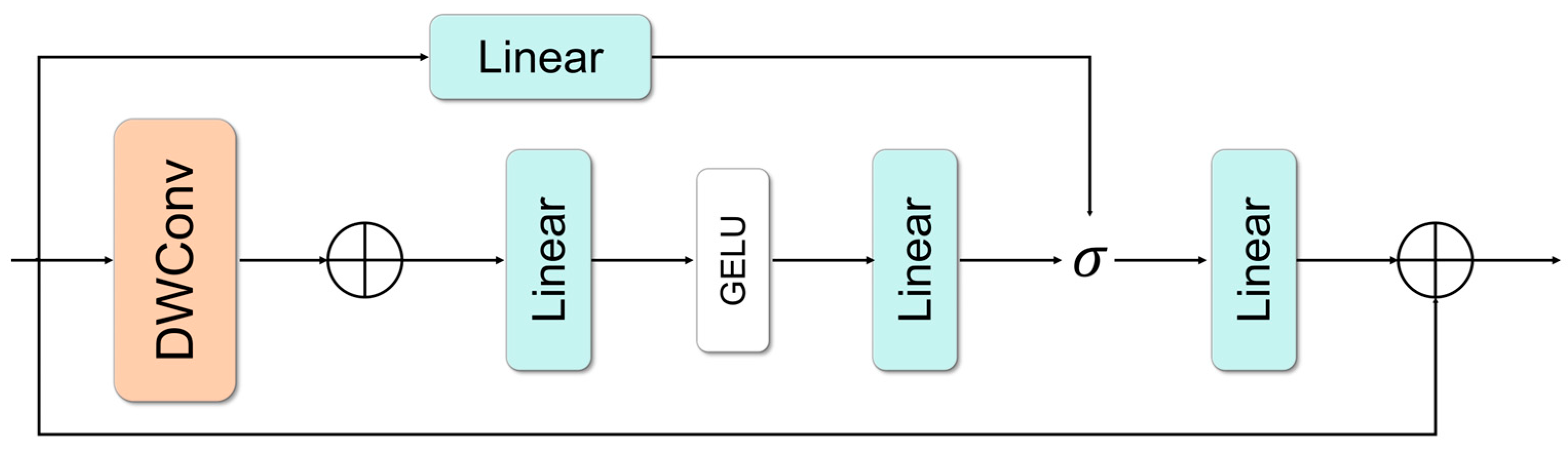

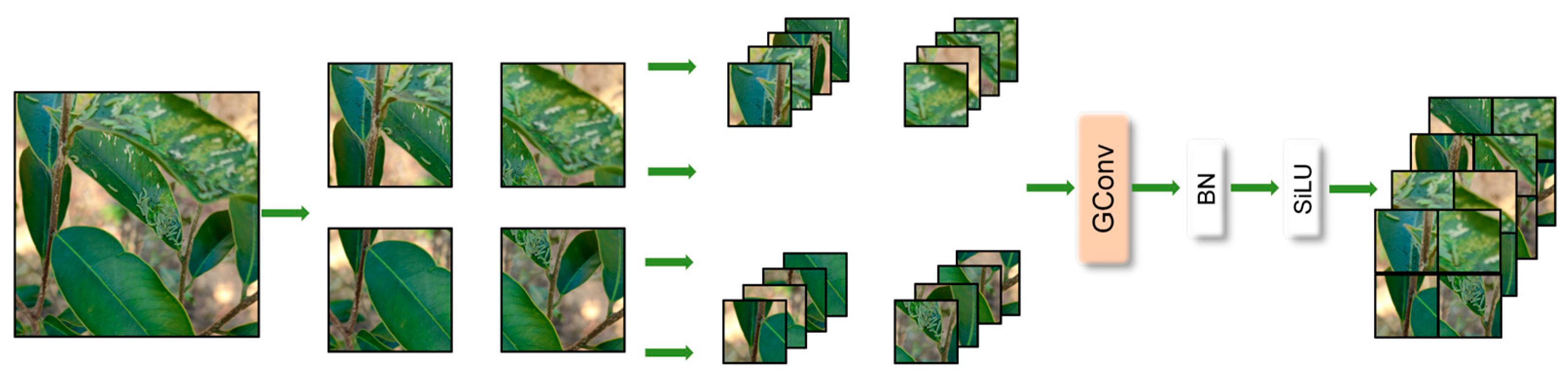

Spatial shuffle downsampling is implemented via the Grouped Spatial Shuffle Downsampling module (GSD). By utilizing pixel rearrangement and grouped convolution operations to replace the convolutional downsampling method, this approach effectively reduces feature resolution while preserving fine-grained spatial details.

For small object optimization, a loss function incorporating the Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) metric is introduced. This method models bounding boxes as Gaussian distributions to enhance robustness in detecting minute pests.

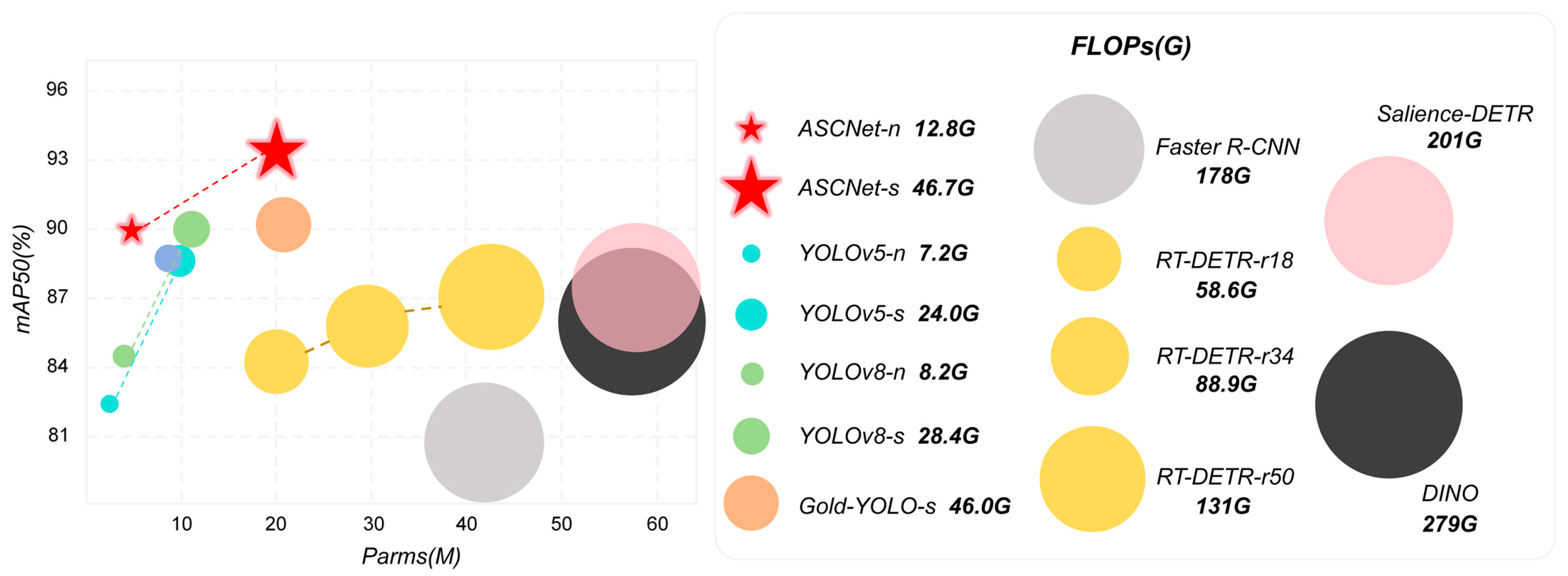

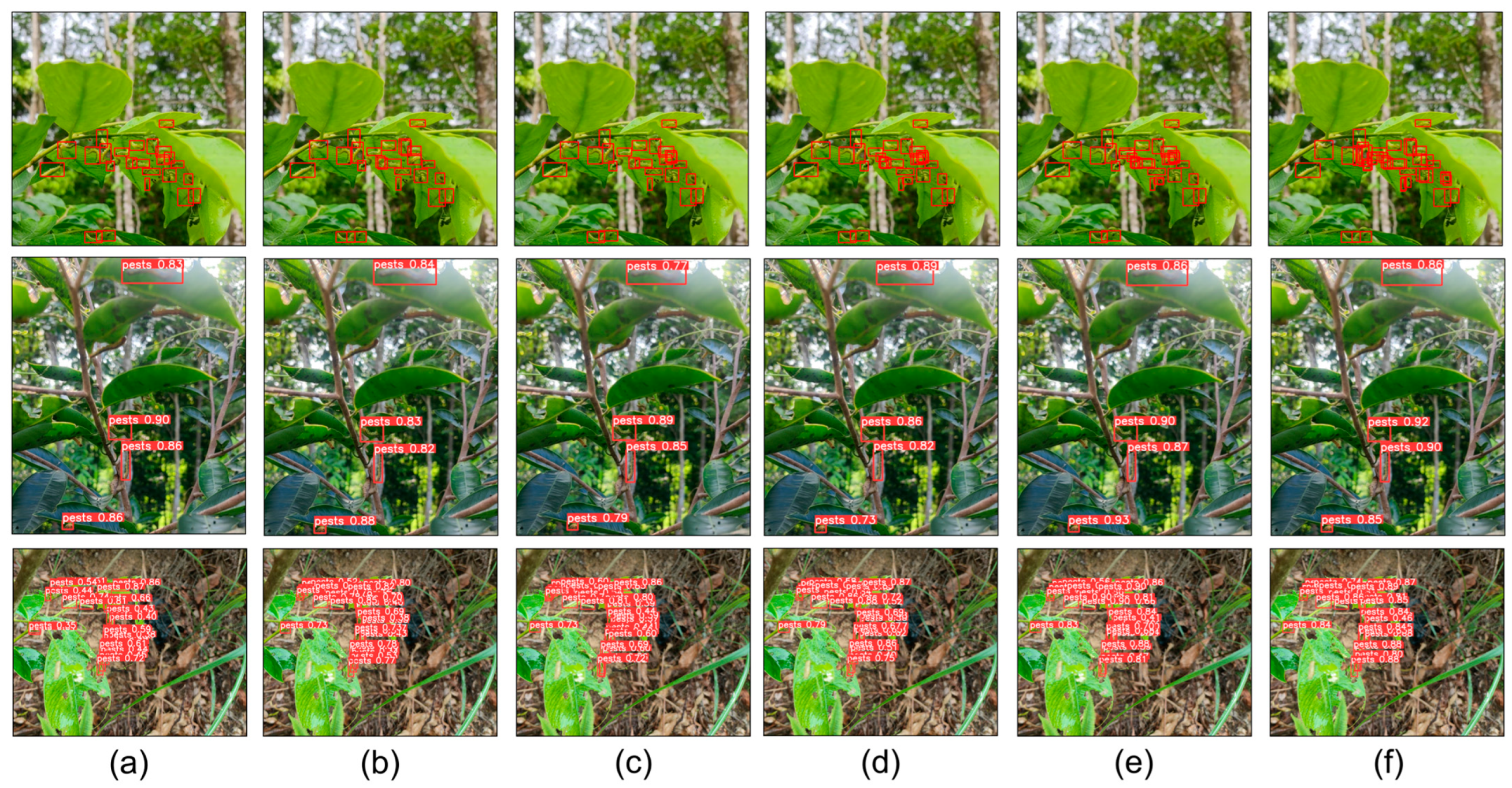

Extensive experiments conducted on the newly constructed agarwood pest dataset demonstrate that ASCNet achieves outstanding performance while maintaining practical efficiency, thereby providing a reliable solution for intelligent pest monitoring in the cultivation of high-value timber tree species.

4. Discussion

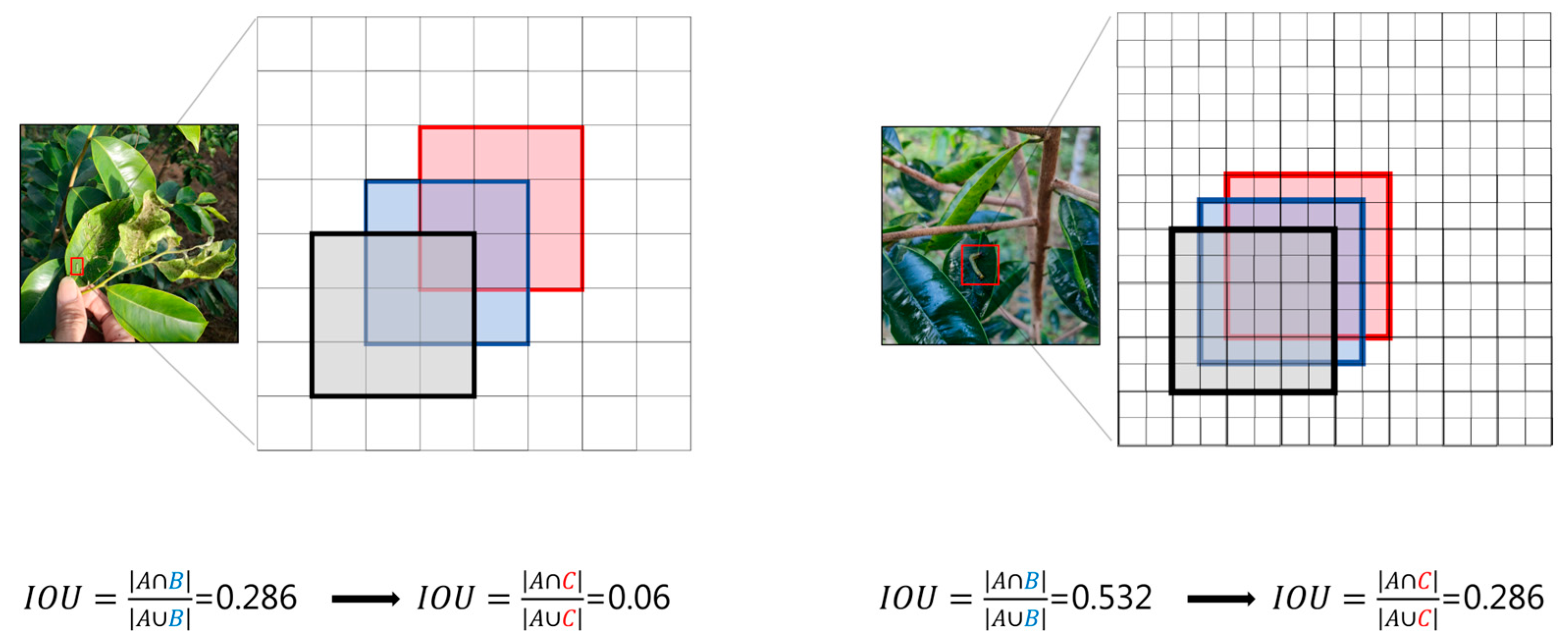

This study demonstrates that the proposed ASCNet model achieves outstanding performance levels in pest detection on Aquilaria sinensis leaves, outperforming various mainstream CNN- and Transformer-based detectors. Its superior performance arises from the innovative integration of state space models with convolutional neural networks, which mitigates the limited receptive fields of CNNs and the quadratic complexity of Transformers. The ASBlock‘s dual-path adaptive fusion mechanism dynamically balances global context and local features. This capability is essential in complex agricultural settings, where pests may be morphologically diverse, occluded, or cluttered within the background. ASCNet-s attains a recall of 87.8%, confirming the state-space pathway’s efficacy in capturing long-range dependencies and minimizing missed detections. The Grouped Spatial Shuffle Downsampling (GSD) module substantially reduces information loss during downsampling, preserving fine details critical for tiny pest detection. ASCNet-s leads all compared methods in multi-scale metrics, underscoring its robust performance. Incorporating Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) into the loss function further enhances small object detection; NWD models bounding boxes as Gaussian distributions, offering a geometrically stable similarity measure compared to IoU, which is sensitive to minor positional shifts. Ablation studies on the NWD weight coefficient confirm that nwd_ratio = 0.3 optimally boosts small object detection without compromising overall accuracy.

Despite these advances, limitations remain: the dataset is from a single geographic region, potentially limiting generalization to other Aquilaria cultivation areas with different pests or imaging conditions. Future work should include cross-regional validation and more diverse pest categories to improve robustness. Moreover, while ASCNet balances accuracy and computational cost well, further optimization is required for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices in agriculture. Techniques like model quantization, pruning, and distillation are promising avenues for future research.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the critical challenge of detecting tiny pests on agarwood leaves, where conventional deep learning models often struggle to balance accuracy and efficiency. The Adaptive State-space Convolutional Fusion Network (ASCNet) is introduced, a novel framework that enhances feature representation by integrating the long-range dependency modeling capability of state-space models with the local feature extraction strengths of convolutional networks. This integration is realized through an Adaptive State-space Convolutional Fusion Block (ASBlock), which adaptively fuses global context with local details. Additional contributions include a Grouped Spatial Shuffle Downsampling (GSD) module, which preserves spatial information during resolution reduction, and a Normalized Wasserstein Distance (NWD) loss that improves localization robustness for small objects. Evaluated on the novel Agarwood Pest Dataset, ASCNet demonstrates distinct advantages over mainstream detectors. Compared to the CNN-based YOLOv8-s, ASCNet-s achieves a superior balance, improving mAP@50:95 by 6 points (71.2 ± 0.3% vs. 65.5%) with a moderate increase in parameters. Against the Transformer-based RT-DETR-r50, it shows a 9.5-point lead in mAP@50:95 while using less than half the computational cost (46.7 vs. 131 GFLOPs). These results confirm that ASCNet successfully navigates the inherent trade-off between the limited receptive fields of CNNs and the high computational complexity of Transformers, establishing a new state-of-the-art for this specific task.

ASCNet provides a robust and efficient solution for intelligent pest monitoring in agarwood cultivation, establishing a versatile paradigm adaptable to other agricultural vision tasks involving small object detection in complex environments. Compared to existing approaches, its primary advantages lie in its balanced design: it mitigates the limited receptive fields of CNNs and the high computational complexity of Transformers through efficient state-space modeling, while the GSD module and NWD loss specifically enhance performance for tiny pests. However, several limitations should be noted. The model’s validation is currently based on a dataset from a specific geographical region, which may affect its generalizability to other cultivation environments with different pest species or imaging conditions. Furthermore, while designed for efficiency, its deployment on resource-constrained edge devices may require further optimization, such as model quantization or pruning, to achieve real-time performance in all field scenarios. Future work will therefore focus on three key directions to address these limitations and advance practical application: (1) enhancing cross-environment generalization through domain adaptation techniques; (2) exploring multimodal data fusion incorporating environmental or spectral information for richer contextual understanding; and (3) optimizing the model architecture and inference pipeline for real-time deployment on edge devices in smart agriculture systems.