Abstract

This paper presents a unified framework for constructing two-branched fuzzy implications and families of copulas based on the same composition principles involving monotone and convex functions. The proposed methodology yields operators with a genuine dual structure, where each branch satisfies distinct boundary and monotonicity conditions while remaining consistent with the general axioms of copulas. By systematically combining monotone generators with convex transformations, new families of fuzzy implications and copulas are obtained, both exhibiting enhanced analytical properties such as strengthened two-increasing behavior, adjustable dependence strength, and flexible convexity with continuous transitions. Convexity ensures the two-increasing property, while continuity guarantees the completeness and mathematical soundness of the constructions. Remarkably, certain copulas produced under this framework display Archimedean-like features—symmetry and associativity—thus providing new theoretical instruments for the advancement of fuzzy logic and dependence modeling.

MSC:

26B25

1. Introduction

Fuzzy negations [1,2,3,4], fuzzy implications [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], and copulas play a pivotal role in many areas of modern research. It is well known that in the contemporary literature there is a great need for the construction of copula and fuzzy implication generators [15,16,17,18,19], as research is rapidly advancing and development is taking place in all fields. This type of convergence favors a variety of newer constructions. While numerous construction methods for copulas have been developed, the occurrence of two-branched fuzzy implications and copulas [20,21,22,23] remains extremely rare. This paper introduces a unified framework for generating innovative classes of copulas through the composition of monotone and convex functions. The proposed methodology not only extends classical approaches but also yields copulas exhibiting distinctive properties, such as Archimedean-type symmetry [20,21,22,23,24,25] and strong connectedness, underlining their importance in modeling uncertainty, dependence, and information aggregation [26,27,28].

Although numerous studies have examined the interplay between fuzzy implications and copulas [29,30], none have explicitly addressed the structural and analytical advantages of two-branched formulations. Classical works such as those of Mesiar and Kolesárová [21,31] or Massanet [8] and Pradera [4] remain confined to single-branched or quasi-copula frameworks, where the construction depends on a unique monotone path. These approaches, although mathematically consistent, offer limited flexibility and cannot capture asymmetric or composite monotonic behaviors across the unit square.

The proposed two-branched architecture transcends these limitations by dividing the copula domain into two coordinated monotone branches. Each branch governs a distinct dependence region, thus enabling asymmetric yet continuous transitions between regimes of convexity and concavity. This separation produces richer geometric adaptability and enhanced analytical control, allowing the resulting copulas and implications to reproduce subtle dependence patterns that single-branched models fail to express.

Furthermore, the two-branched framework introduces structural stability: local monotonicity deviations in one branch can be compensated by the complementary branch, preserving the global two-increasing property. This internal redundancy, absent in all prior models (Mesiar & Kolesárová [21], Massanet [8] and Pradera [4]), ensures that the resulting copulas remain valid under a broader class of generating functions, including non-linear or partially convex mappings. Additionally, the symmetrical design of the branches allows analytic enforcement of copula symmetry when required, while retaining the capacity for asymmetric modeling when the branches differ.

A crucial innovation of the present framework is that it constructs both fuzzy implications and copulas through composition of monotone functions, which in many cases behave as fuzzy negations or strictly increasing transformations. This functional composition mechanism allows the inherited properties of the component functions—such as monotonicity, convexity, or continuity—to be directly transferred to the final construction. Such an approach yields analytical clarity and a systematic way to generate valid copulas and implications from elementary building blocks, a method that has not yet appeared in any of the existing literature.

Finally, the dual-path structure permits parametric modulation between branches, enabling the formation of entire families of copulas that share a unified analytical framework but exhibit distinct dependence intensities. This internal diversity within a single functional rule constitutes a major conceptual advancement beyond all known single-branch constructions.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 recalls fundamental definitions and preliminary properties helping establish the results. Section 3 develops the construction framework in six different theorems—two theorems on two-branched fuzzy implications with the use of fuzzy negations [1,2,3,4] and four theorems on Copulas, all based on monotone and convex function composition. Section 4 organizes the ideas surrounding the results of the present article, presenting their uses, applications, and significance, and provides insights that could serve as a basis for future research within the literature of fuzzy logic and stochastic connectives. Section 5 concludes the work and outlines directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

The fundamental concept underpinning the present study originates from a previously established construction [] [29] that introduced a multidimensional formula with remarkable theoretical and practical potential. This formula, as initially presented, facilitates the generation of fuzzy negations and fuzzy implications, and—with a minor structural modification—can also be employed for the generation of copulas.

Building upon this foundational idea, the current paper extends and generalizes the aforementioned construction. By utilizing the same functional framework, we develop a series of mathematical formulations which, under suitable conditions, give rise either to fuzzy implications or to copulas, depending on the structural configuration of the generating functions. This approach highlights the intrinsic connection between these two mathematical frameworks and provides a unified basis for further theoretical developments.

To further enhance this framework, we introduce the necessity of developing two-branched fuzzy connections, which constitute a natural extension of the proposed methodology. The present work investigates the theoretical implications and advantages arising from the two-branched construction of such functions. This approach ensures superior compliance with boundary conditions, preservation of the two-increasing property, as well as enhanced symmetry and structural coherence within the resulting formulations.

All the functions used in the following sections for proving the theorems and for constructing the fuzzy implications and copulas possess certain specific properties. They are strictly monotone on the closed interval , well defined, and invertible. The strictly increasing functions satisfy and , while the strictly decreasing ones satisfy and . In both cases, their inverse functions are properly defined. Throughout this paper, the strictly increasing functions are denoted by the letter and the strictly decreasing functions by the letter ; the same notation is used for their corresponding inverse functions.

In this section Definitions 1–5 focus exclusively on the formation of fuzzy negations, while Definitions 6 and 7 address the development of fuzzy implications, and Definitions 8–14 [20,21,22,23,24,29] relate to the constructions proposed in the field of copulas. Between Definitions 5 and 6, a table that highlights the most important and well-known classes of fuzzy negations is inserted. It is also important to recall the definition of the fuzzy implication I(x,y) = [29]. At this point, a dedicated bibliographical note may be provided, referencing key works on copula construction, their properties, the Archimedean family, and fuzzy copulas.

Definition 1

(see [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,11,12,13]). The function is a fuzzy negation if the following properties are applied:

Definition 2

(see [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,11,12,13]). A fuzzy negation N is called strict if the following properties are applied:

Definition 3

(see [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,11,12,13]). A fuzzy negation N is called strong if

Definition 4

(see [1,2,3,4,8,9,10,11,12,13]). The solution of the equation is called equilibrium point of N. If the function N is continuous the equilibrium point is unique.

Definition 5

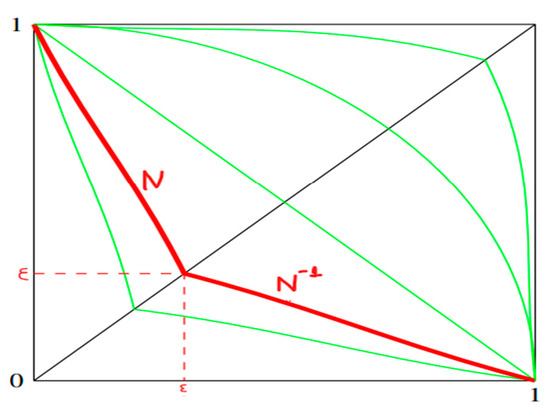

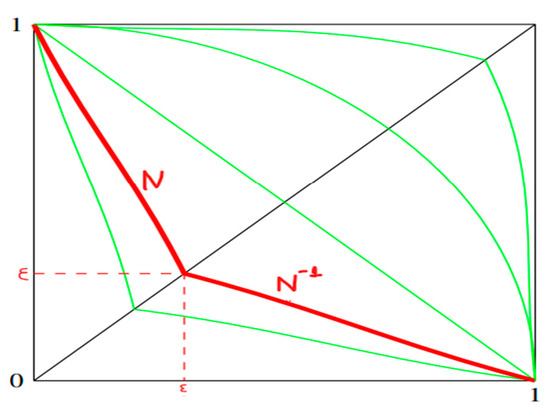

([1]). Strong branching fuzzy negations can be produced, while in every branch there is a decreasing function. If is a fuzzy negation which is not necessary, a strong negation and where ε is the equilibrium point of . So, if is any continuous fuzzy negation in the interval [0,1] then the following form [12] produces strong fuzzy negations and in our case rational fuzzy negations (

Figure 1

).

Figure 1.

The above figure illustrates a two-branched strong fuzzy negation, incorporating both the function and its inverse .

The above formula will be generalized by using two functions one decreasing and one increasing.

Definition 6

(see [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]). A function is called a fuzzy implication, if it satisfies, for all the following conditions:

Definition 7

(see [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]). If I is fuzzy implication, then the function with the form

is called natural negation of I.

Definition 8

([26]). Let I be a nonempty interval of R. A function f from I to R is convex if and only if,

Definition 9

([20,21,22,23,24,29]). A function is called copula if it satisfies the following properties:

The C-volume of a rectangle must be not negative e.g.,

for each and where ,

Definition 10

([20,21,22,23,24,29]). If the function C is a copula, then the function in form

Definition 11

([20,21,22,23,24,29]). Let be continuous, strictly decreasing, and convex function such that, and let be the pseudo-inverse. Let be defined by

Then, C is an Archimedean Copula.

Definition 12

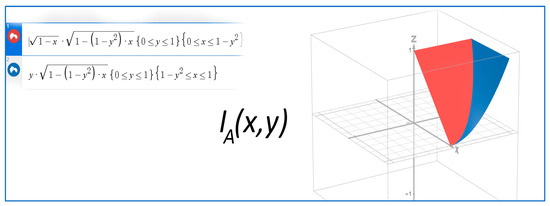

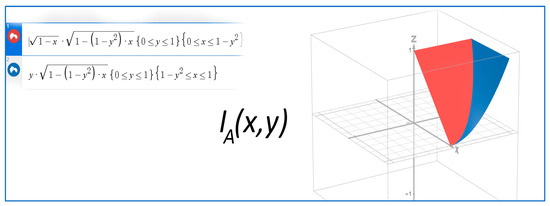

([29]). Let the functions continous, well defined, then as I(x,y) = , and f(x) decreasing and f(0) = 1.

Definition 13

([29]). Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous. The function

Definition 14

([29]). Knowing that for a function to be 2-increasing must satisfy the inequality

3. Results

In this chapter, the results of the research will be presented, each accompanied by complete proofs. It concerns the following six theorems: two of them provide constructions of two-branched fuzzy implications, while the remaining four introduce constructions of two-branched copulas. It will be observed that these constructions are based on monotone, strictly decreasing, and convex functions—essentially negations that also possess the property of convexity. Two-branched fuzzy implications are particularly rare, and it will be seen how they arise with the aid of theorems that have been previously established. On the other hand, the copulas exhibit properties reminiscent of Archimedean copulas, and the proof of the two-increasing condition is achieved through the convexity of the functions employed.

What is particularly important and should be emphasized is that all the following constructions are based on a specific underlying logic. They are built around the formula introduced in Definition 12 [29]. This formula, with some minor variations—either by changing the functions from decreasing to increasing, or by interchanging the variables and —generates all the subsequent theorems. This could also serve as an excellent starting point to address the question of whether fuzzy implications and copulas can share common generators.

3.1. Two-Branched Fuzzy Implications

Using Definition 12 which means that if there is and continuous, decreasing with f(0) = 1 and f(1) = 0 it is proven that I(x,y) = is a fuzzy implication. That will lead in the next theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let the functions continous, well defined, decreasing with f(0) = 1 and f(1) = 0. Let ε be the equilibrium point which verifies the equality f(x) = y (f(y) = ε). Then, is a fuzzy implication.

Proof of Theorem 1.

Monotonicity in brunch:

With respect to x: For every ⇔

So, I multiply (23) × (24) and obtain:

With respect to y: For every ⇔ .

For x ≥ 0 ⇔

Monotonicity in brunch

With respect to x: For every y ≥ 0 multiplied it with (21) there is:

With respect to y: For every ⇔

Again, for every ⇔ there for

All six fuzzy implication properties are fulfilled, thus is a fuzzy implication. □

Remark 1.

If it is takken into account Definition 12, that I(x,y) = is a fuzzy implication, then we can redifine Theorem 1 as:

Example 1.

Let, and = then for every (x,y) the function

is a fuzzy implication.

Boundary Conditions

Monotony Conditions

It is easy to prove the monotonicity conditions using the definition of monotonicity. It will be proven, as an example, the monotonicity of with respect to y.

And multiply (37) × (36) so we have

The same way it is proven than all monotonicity properties are fulfilled and therefore

is a fuzzy implication (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The graphical illustration corresponding to the aforementioned example of the fuzzy implication.

Theorem 2.

Let the functions continous, well defined, decreasing with f(0) = 1 and f(1) = 0. Let also g continous, well defined, increasing with g(0) = 0 and g(1) = 1, with ε be the equilibrium point which verifies the equality f(x) = y (f(y) = ε). Then, is a fuzzy implication.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Monotonicity in brunch:

With respect to x: For every

So, I multiply (39) × (40) and obtain:

With respect to y: For every

Monotonicity in brunch:

With respect to x: For every y ≥ 0 multiplied it with (39) there is:

With respect to y: For every

Again, for every ⇔ there for

All six fuzzy implication properties are fulfilled, thus is a fuzzy implication. □

Remark 2.

If Definition 12 [29] is taken into account, that I(x,y) = is a fuzzy implication, then we can redifine Theorem 2 as:

To be a fuzzy implication.

Remark 3.

If we assume that the variable exhibits the same properties as the function , then we can state that Theorems 1 and 2 are equivalent. Consequently, it can be inferred that Theorem 2 is a generalization of Theorem 1.

Example 2.

Let, g(x) = and = then for every (x,y) the function

is a fuzzy implication.

Boundary Conditions

Monotony Conditions

It is easy to prove the monotonicity conditions using the definition of monotonicity. It will be proven, as an example, the monotonicity of with respect to y.

And multiply (53) × (54) so we have

The same way it is proven than all monotonicity properties are fulfilled and therefore is a fuzzy implication.

3.2. Two-Branched Copulas

Below, there will be presented a series of new forms of copulas, which will be exclusively two-branched and will be based on a general framework derived from the same formula on which the previous fuzzy implications were founded. The only difference is that this time, the composed functions will be strictly increasing.

Theorem 3.

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous, and k > 0. The function , when the function

.

Proof of Theorem 3.

Firstly, there will be presented the boundary conditions, and finally the 2-increasing property.

We define a bivariate function C: → [0, 1] with two branches, where the first branch is for x ≤ y and the second branch is for x ≥ y.

Recall that:

By swapping x and y, we obtain:

That proves that Copula holds the Symmetric property. If the 2-increasing property is proven for , it also holds for as well.

Continuity on the diagonal: at x = y, both branches coincide, hence is continuous.

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument: the Copula (x, y) is 2-increasing if ≥ 0 [Definition 14, Equation (21)] Positive partial derivatives in each domain (x ≤ y or x ≥ y) given the sign conditions already established for and .

Considering is convex, we have that )″(x) ≥ 0. So:

indeed because ≥ 0, ≥ 0 (convexity), ≥ 0 and y ≥ 0, k > 0.

Conclusion: The mixed partial derivative of is positive for . Due to the fact that(x, y) is a symmetric Copula, exactly the same applies for function , hence ≥ 0. □

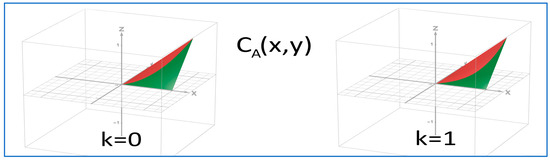

Example 3.

Let and for x ≥ 0. For every k ≥ 0 the function with the formula

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument:

Which proves is a 2-increasing Copula with the symmetric property (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Two-branched Copula’s behavior for k ≥ 0 value. Left for k = 0 and right for k = 1.

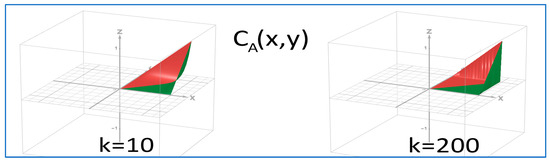

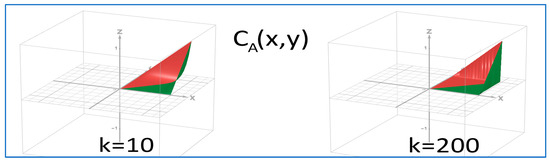

Remark 4.

It should be noted here that when the parameter reaches very large values, the above copula tends to become degenerate, since its values across the entire domain approach zero (

Figure 4

, right image).

Figure 4.

Two-branched Copula’s behavior for k ≥ 0 extended values k = 10 at left and k = 200 at right.

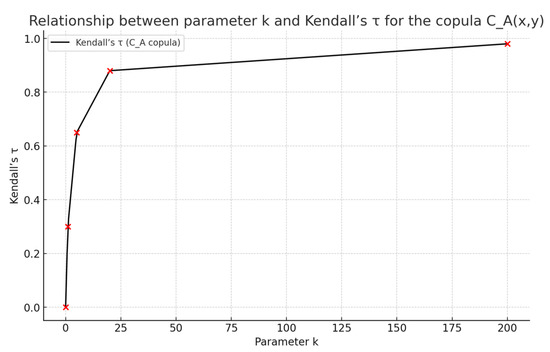

Remark 5.

To emphasize the choice of this example and to highlight the relationship between monotonicity, convexity, and the variation in parameter , we employ Kendall’s coefficient. The analytical link between convexity, monotonicity, and Kendall’s coefficient τ, as can be seen in Table 1 arises from the fact that τ is defined through the mixed partial derivative of the copula,

Table 1.

Relationship between copula properties and Kendall’s coefficient.

The term quantifies the two-increasing property of the copula, which is directly governed by the monotonicity and convexity of the generating functions.

When the generators are strictly increasing and convex, the copula surface becomes steeper and more concentrated around the diagonal , which increases the mixed partial derivative and thus the value of τ.

This relationship is not limited to numerical examples but generally holds for all constructions where the copula is obtained through composition of monotone and convex functions satisfying the standard boundary conditions.

Remark 6.

The choice of exhibits all the analytical characteristics required for the proposed two-branched construction. Specifically, is strictly increasing and convex on the interval .

The strict monotonicity ensures that the resulting copula satisfies the two-increasing property and the standard boundary conditions, while convexity determines the curvature of the copula surface, yielding a smooth and symmetric shape along the main diagonal .

As the parameter increases, the combined effect of monotonicity and convexity of intensifies the concentration of along the diagonal, leading to higher values of Kendall’s and thus stronger dependence.

Importantly, this analytical behavior is not restricted to this example but holds generally for all two-branched copulas constructed via compositions of monotone and convex functions satisfying the standard copula axioms. The graphical representation (Figure 5) further supports this observation, showing that the surface steepness and diagonal concentration increase consistently with , in full accordance with the convex nature of .

Figure 5.

Illustrative relationship between the parameter and Kendall’s coefficient for the two-branched copula . As increases, both branches become more concentrated along the main diagonal, resulting in higher values of Kendall’s and thus stronger positive dependence.

Remark 7.

For the value , we observe that both branches of the copula become identical to the copula , which is Archimedean. Through a simple substitution, it can be verified that the associativity property is also satisfied. Therefore, for k = 0 the copula becomes an Archimedean copula.

Remark 8.

Theorem 3 is equivalent to the below:

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

is a Copula.

Remark 9.

By taking into consideration Definition 13 [29] and the analytical form of the Archimedean copula presented in Equation (20) (x,y) = , the aforementioned theorem can be reformulated and expressed in the following equivalent form:

The preceding formula has been shown to preserve symmetry, though it fails to satisfy the associativity property. Consequently, although it can generate or include an Archimedean-type copula, it does not fully comply with the defining criteria of a true Archimedean copula.

Theorem 4.

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

.

Proof of Theorem 4.

holds the Symmetric property. If the 2-increasing property is proven for , it holds for as well.

Continuity on the diagonal: At x = y, both branches coincide, hence is continuous.

Copula margins: For the proof of the first condition after replacing

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument: the Copula (x, y) is 2-increasing if ≥ 0 [Definition 15, Equation (21)] Positive partial derivatives in each domain (x ≤ y or x ≥ y) given the sign conditions already established for and .

Considering is convex, we have that)″(x) ≥ 0. So:

indeed because ≥ 0, ≥ 0 (convexity), ≥ 0 and y ≥ 0, k > 0.

Conclusion: The mixed partial derivative of is positive for . Due to the fact that(x, y) is a symmetric Copula, the same applies for function , hence ≥ 0. □

Remark 10.

It would be useful to include a few remarks on this point. First, when the parameter takes very large values and tends to infinity, the copula function becomes degenerate, exhibiting values that approach zero throughout the entire domain. When , we can observe that the resulting function represents a special case of the copula presented in the previous theorem. This occurs when the variables and in each respective branch are replaced by the functions and , respectively. We can state that Theorems 3 and 4 are equivalent. Consequently, it can be inferred that Theorem 3 is a generalization of Theorem 4 when k = 1.

Example 4.

Let and for x ≥ 0. For every k > 0 the function with the formula

The monotonicity property for the upper brunch:

According to Definition 13, any copula obtained through the composition of a convex and strictly increasing outer function with monotone inner mappings preserves the two–increasing property.

In the present construction, the external function involved in both branches of is positive, convex, and strictly increasing, and it is multiplied by another positive and convex function , which is itself strictly increasing on .

The product of two positive convex functions remains convex and positive on the same interval, and therefore the overall composition retains convexity and monotonicity.

Consequently, by the general principle stated in Definition 13, the constructed two-branched copula is two-increasing.

Due to the inherent symmetry of its definition, this property holds for both branches simultaneously. This proves is a 2- increasing Copula with the symmetric property.

It is straightforward, by simple substitution, to verify that the boundary conditions of the copula are satisfied.

Remark 11.

Kendall’s concordance coefficient of the proposed two-branched copula is given by

where .

Although no closed analytical form exists for arbitrary , the integral can be easily evaluated numerically.

For , the copula reduces to the Fréchet–Hoeffding upper bound , yielding . Hence, the family forms a smooth one-parameter transition from perfect to weaker positive dependence. Compared with classical Archimedean copulas (Clayton, Frank, Gumbel), the proposed construction offers several advantages: it is explicitly two-increasing, symmetric, and directly compatible with function–composition frameworks used in fuzzy implications.

Its parameter simultaneously controls both the dependence strength and the curvature of the root term, leading to stronger concentration around the main diagonal and enhanced modeling flexibility.

Moreover, unlike Archimedean families that approach perfect concordance only asymptotically, the present copula attains it exactly for , providing a simple yet powerful representation of strong positive dependence.

Remark 12.

Theorem 4 is equivalent to the below:

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

.

Theorem 5.

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

.

Proof of Theorem 5.

holds the Symmetric property. If the 2-increasing property is proven for , it holds for as well.

Continuity on the diagonal: At x = y, both branches coincide, hence is continuous.

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument: the Copula (x, y) is 2-increasing if ≥ 0 [Definition 15, Equation (21)] Positive partial derivatives in each domain (x ≤ y or x ≥ y) given the sign conditions already established for and .

Considering is convex, we have that)″(x) ≥ 0. So:

Monotonicity in each argument: the Copula (x, y) is 2-increasing if ≥ 0 [Definition 15, Equation (21)] Positive partial derivatives in each domain (x ≤ y or x ≥ y) given the sign conditions already established for and .

Considering is convex, we have that )″(x) ≥ 0. So:

stands because ≥ 0, ≥ 0 (convexity), ≥ 0 and y ≥ 0, k > 0.

Conclusion: The mixed partial derivative of is positive for . Due to the fact that(x, y) is a symmetric Copula, exactly the same applies for function , hence ≥ 0. □

Example 5.

Let and for x ≥ 0. For every k > 0 the function with the formula

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument:

Which proves is a 2-increasing Copula with the symmetric property.

Remark 13.

Theorem 5 is equivalent to the below:

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

Remark 14.

By taking into consideration Definition 13 [29] and the analytical form of the Archimedean copula presented in Equation (20) (x,y) = , the aforementioned theorem can be reformulated and expressed in the following equivalent form:

It has been demonstrated that the above formula satisfies the property of symmetry, but not the property of associativity. Therefore, while it may encompass an Archimedean copula, it does not itself fulfill all the necessary conditions required for a function to be classified as a genuine Archimedean copula.

Theorem 6.

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

.

Proof of Theorem 6.

holds the Symmetric property. If the 2-increasing property is proven for , it holds for as well.

Continuity on the diagonal: at x = y, both branches coincide, hence is continuous.

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument: the Copula (x, y) is 2-increasing if ≥ 0 [Definition 15, Equation (21)] Positive partial derivatives in each domain (x ≤ y or x ≥ y) given the sign conditions already established for and .

Considering is convex, we have that)”(x) ≥ 0. So:

is valid because ≥ 0, ≥ 0 (convexity), ≥ 0 and y ≥ 0, k > 0.

Conclusion: The mixed partial derivative of is positive for . Due to the fact that(x, y) is a symmetric Copula, exactly the same applies for function , hence ≥ 0. □

Example 6.

Let and for x ≥ 0. For every k > 0 the function with the formula

Copula margins:

For the proof of the first condition after replacing:

And the second condition:

Monotonicity in each argument:

Which proves is a 2-increasing Copula with the symmetric property.

Remark 15.

Kendall’s coefficient (τ) is a non-parametric measure of concordance that quantifies the strength and direction of dependence between two variables based on their ranked observations. The possible values of the Kendall’s coefficient range from −1 to +1, each representing a distinct level of dependence between the two variables. The computed Kendall’s coefficient clearly indicates that the proposed two-branched copula exhibits a strong and consistent positive dependence structure between its arguments. Compared to the classical Archimedean families such as Clayton, Frank, and Gumbel, this level of dependence is notably high and exhibits a symmetric pattern, simultaneously encompassing both upper- and lower-tail characteristics.

While the Clayton and Gumbel copulas tend to emphasize dependence in a single tail region, the present two-branched formulation achieves a balanced and smooth dependence throughout the entire unit square. This symmetry arises naturally from the bidirectional construction of the copula, which preserves both the two-increasing property and the strict monotonicity of its generating functions. Consequently, the model introduces a more flexible and robust dependence framework that conceptually bridges the gap between traditional Archimedean copulas and symmetric dependence models.

Remark 16.

Theorem 4 is equivalent to the below:

Let the function continuous, strictly increasing, and convex, g(0) = 0, g(1) = 1, with continuous and k > 0. The function , when the function

is a Copula.

Remark 17.

It can be said that Theorem 5 is a generalization of Theorem 6. This occurs when the variables and in each respective branch of Theorem 5 are replaced by the functions and , respectively. In that way, we can state that Theorems 5 and 6 are equivalent.

Remark 18.

It can be readily observed that all the theorems concerning copulas revolve around a common structural form, as previously mentioned. Minor variations—where the variables and are replaced by a strictly increasing function or its inverse—yield all the aforementioned theorems. Consequently, in specific cases, one theorem may overlap with or be equivalent to another.

Remark 19.

Despite the fact that two of the four theorems above can be expressed in a form that includes an Archimedean copula within their formulation, only based on these constructions can a genuine Archimedean copula ( 0) be constituted. It is the only case where the associativity property is satisfied.

4. Discussion

The main objective and central theme of this article is to present the potential for constructing fuzzy implications [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] and copulas [20,21,22,23] through the composition of monotonic and convex functions. Analytically, the two-branched constructions maintain all standard copula properties (boundary conditions, 2-increasing behavior, and symmetry) while introducing an additional parameter control that allows independent adjustment of each branch. This dual-branch structure provides greater flexibility in modeling asymmetric or heterogeneous dependence patterns, while classical single-branched copulas are limited by a single generator and fixed curvature. Graphically, the two-branched copulas exhibit smoother transitions between upper and lower tails and can emulate both Archimedean and comonotonic behaviors depending on the parameter k. Importantly, this comparative behavior is not specific to the examples provided but holds generally for all two-branched copulas constructed through compositions of monotone and convex functions. The analytical framework extends beyond the illustrative cases shown.

A compelling reason for research in this field to revolve around two-branched copulas lies in their dual nature—a harmonious balance between analytical rigor and expressive flexibility, capable of capturing the subtle asymmetries and hidden structures that single-branch forms often overlook.

Two-branched copulas provide a highly flexible and theoretically rich framework compared to classical single-branch forms as it can be seen in Table 2. By dividing the unit square into two functional regions, they can satisfy all boundary conditions while preserving essential properties such as symmetry and two-increasingness. Their dual structure allows each branch to model distinct dependence patterns (e.g., for x < y and x > y), enabling asymmetric or heterogeneous behaviors often found in real data. Each branch can be built from a separate monotone or convex generator, offering local control and stability even in non-differentiable regions. Moreover, their strong structural analogy to two-branched fuzzy implications highlights a unified theoretical link between probabilistic dependence and fuzzy logic reasoning. Overall, two-branched copulas achieve both greater mathematical robustness and broader modeling versatility, making them powerful tools for advanced dependence analysis.

Table 2.

The table below demonstrates that the proposed two-branched copulas extend the modeling capacity of classical single-branched forms by introducing independent control of convexity and monotonicity on each branch.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no existing study in the literature that directly connects function composition with the construction of copulas and fuzzy implications.

Although numerous works have analyzed different types of fuzzy implications and dependence structures, none of them establish a direct theoretical framework based on monotone or convex function composition leading simultaneously to both a copula and a fuzzy implication.

In contrast to the traditional Archimedean copulas, which exhibit distinct and often asymmetric dependence patterns, the proposed two-branched copula demonstrates a fully symmetric behavior across the main diagonal.

The Clayton and Gumbel copulas present tail dependence concentrated exclusively in the lower and upper regions, respectively, while the Frank copula, although symmetric, lacks any tail dependence altogether.

The present construction achieves a balanced representation of dependence strength in both tails simultaneously, providing a unified form that combines upper and lower tail responsiveness within a single symmetric structure.

Moreover, unlike the Archimedean families that inherently satisfy the associativity property due to their single-generator form, the two-branched copula relaxes this strict Archimedean associativity yet maintains global coherence through its functional composition mechanism.

This structural distinction allows the model to preserve essential copula properties while offering enhanced flexibility in capturing symmetric dependence behaviors that are not attainable through classical Archimedean frameworks. It should also be noted that, as previously discussed, for certain specific values of the parameter (e.g., ), the two-branched copulas take the form of an Archimedean copula.

Certain multi-branched approaches have been briefly discussed in the research of Mesiar and Kolesárová [31], yet these constructions remain only partially developed, without explicit analytical direction or reliance on compositional methods.

Similarly, the classical works of Nelsen [21] and Baczyński, Grzegorzewski, and Mesiar [20] focus primarily on the foundational and structural properties of copulas and fuzzy implications, rather than on their unified generation through functional operators.

All other related studies, including those by Klement [7], Pradera [4], and Massanet [8], explore general frameworks for aggregation or implication, but none propose a bidirectional or two-branched composition scheme linking these mathematical connectors.

Therefore, the present work introduces a novel and coherent theoretical approach, offering for the first time a systematic method that constructs genuine copulas directly from fuzzy implications via monotone function composition, bridging two domains that until now have remained largely independent.

One can easily observe that the way these structures are formulated reveals that fuzzy implications and copulas are constructed in a very similar manner. In the aforementioned article, they exhibit many common features. The main similarity lies in the formula we presented earlier. Such an observation can provide highly significant insights into the study of how these connectors are constructed.

The possibility of convergence between the generative mechanisms of fuzzy implications and copulas could become a crucial topic for future scientific studies [30]. Could there exist a common mathematical framework through which both fuzzy implications and copulas are simultaneously generated? Could we identify potential mathematical relationships where copulas are derived from fuzzy implications, and fuzzy implications, in turn, from copulas? Could a single mathematical formula capable of producing both at once perhaps be developed?

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in this mathematical study we present six constructions—two fuzzy implications and two copulas—all characterized by their two-branched formulation.

What are the key advantages that make the construction of two-branched fuzzy implications and copulas a particularly meaningful direction of research—combining mathematical precision with flexible structure, and revealing deeper links between dependence modeling and fuzzy reasoning? Let us now examine the advantages offered by the two branches.

- Flexibility in Satisfying Boundary Conditions

Single-branch copulas often fail to simultaneously satisfy all boundary conditions C(x,0) = 0, C(0,y) = 0, C(x,1) = x, and C(1,y) = y, especially when their generator functions are subject to monotonicity or convexity restrictions. Two-branched copulas, on the other hand, allow different mathematical behavior in two separate regions of the unit square [0,1]^2. This provides the flexibility needed to fulfill all boundary conditions without losing important structural properties such as symmetry or the two-increasing condition.

- 2.

- Increased Expressiveness and Adaptability to Data

In applications of probability theory, data analysis, and machine learning, two-branched copulas can represent different dependence structures in the regions x < y and x > y. This capability allows the creation of asymmetric copulas, which can model situations where the intensity or direction of dependence varies. Such modeling flexibility cannot be easily achieved through symmetric single-branch copulas, making two-branched constructions particularly valuable in real-world systems that exhibit heterogeneous or directional dependence.

- 3.

- Preservation of Desirable Mathematical Properties in Each Branch

Each branch of a two-branched copula can be generated by a distinct convex or monotone function, enabling local control and optimization of mathematical properties such as convexity, associativity, and two-increasingness. This approach allows the designer to maintain strong theoretical guarantees on each subdomain, improving the overall robustness and consistency of the copula construction.

- 4.

- Theoretical Connection with Fuzzy Implications

Two-branched copulas have a deep structural analogy with two-branched fuzzy implications, which are logical operators defined in a similar way through function composition. Consequently, these constructions reveal a unified theoretical framework linking probabilistic dependence (expressed through copulas) and fuzzy inference mechanisms (expressed through fuzzy implications). Each branch can represent a logical phase of inference—such as the antecedent and consequent—or alternatively, two regimes of dependence within probabilistic models.

- 5.

- Improved Mathematical Behavior in Non-Differentiable Regions

When the generator function is not differentiable or changes convexity, dividing the copula into two-branches allows for better continuity and smoothness over the entire domain. The two-branch approach ensures that the global two-increasing property remains valid even in the absence of differentiability, while each branch individually maintains desirable analytic features.

Summary

Two-branched copulas offer greater modeling flexibility, mathematical stability, and conceptual alignment with fuzzy implications compared to classical single-branch constructions. They not only enable compliance with all boundary and structural conditions but also introduce the possibility of modeling asymmetric dependencies and local convexity adaptations. This theoretical and functional parallelism between copulas and fuzzy implications suggests a promising direction for developing a unified mathematical framework encompassing both probabilistic and fuzzy-logical connectors, as well as for the possible applications in domains where fuzzy logic and probabilistic reasoning are indispensable, such as artificial intelligence, data analytics, machine learning, and others [31,32].

It is absolutely evident that the present work paves the way for many similar constructions concerning the redirection of fuzzy implications and copulas toward the method of two-branched representations. This is because they provide multiple forms of solutions, as previously mentioned, and because the structural similarity in their construction introduces a new dimension to research. This dimension may lead to further developments that bring these two mathematical connectors even closer in form and function. Future studies are expected to present more extensive constructions with an even deeper mathematical interconnection. The convergence of these concepts appears to be inevitable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G.M.; Methodology, P.G.M.; Validation, B.K.P.; Formal analysis, P.G.M.; Investigation, P.G.M.; Resources, P.G.M.; Writing—review and editing, P.G.M.; Visualization, P.G.M.; Supervision, B.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to my Parents Georgios Mangenakis and Magdalini Mangenaki, as well as to Basil Papadopoulos.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial, or other.

References

- Bustince, H.; Campión, M.; De Miguel, L.; Induráin, E. Strong negations and restricted equivalence functions revisited: An analytical and topological approach. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2022, 441, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedregal, B.C. On interval fuzzy negations. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2010, 161, 2290–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Massanet, S.; Vemuri, N.R. Novel construction methods of interval-valued fuzzy negations and aggregation functions based on admissible orders. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2023, 473, 108722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradera, A.; Beliakov, G.; Bustince, H.; De Baets, B. A review of the relationships between implication, negation and aggregation functions from the point of view of material. Inf. Sci. 2016, 329, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczyński, M.; Jayaram, B. QL-implications: Some properties and intersections. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2010, 161, 158–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczynski, M.; Jayaram, B. (U, N)-implications and their characterization. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2009, 160, 2049–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F.; Klement, E.P.; Meriar, R.; Sempi, C. Conjunctors and their residual implicators: Characterizations and construction methods. Mediterr. J. Math. 2007, 4, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanet, S.; Torrens, J. An overview of construction methods of fuzzy implications. In Advances in Fuzzy Implication Functions; Studies in Fuzziness and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 300, pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczynski, M.; Jayaram, B.; Massanet, S.; Torrens, J. Fuzzy implications: Past, present, and future. In Springer Handbook of Computational Intelligence. Springer Handbooks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczynski, M.; Jayaram, B. On the characterization of (S, N)-implications. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2007, 158, 1713–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massanet, S.; Riera, J.V.; Ruiz-Aguilera, D. On fuzzy polynomials implications. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference of the International Fuzzy Systems Association and the European Society for Fuzzy Logic and Technology (IFSA-EUSFLAT-15), Gijón, Spain, 30 June–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti, M.N.; Papadopoulos, B.K. A Method of Generating Fuzzy Implications from n Increasing Functions and n + 1 Negations. Mathematics 2020, 8, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidou, A.; Konguetsof, A.; Souliotis, G.; Papadopoulos, B. Generator of Fuzzy Implications. Algorithms 2023, 16, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczynski, M.; Jayaram, B. Fuzzy Implications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustince, H.; Pagola, M.; Barrenechea, E. Construction of fuzzy indices from fuzzy DI-subsethood measures: Application to the global comparison of images. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 906–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogiatzis, A.C.; Papadopoulos, B.K. Local thresholding of degraded or unevenly illuminated documents using fuzzy inclusion and entropy measures. Evol. Syst. 2019, 10, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogiatzis, A.; Papadopoulos, B. Global Image Thresholding Adaptive Neuro- Fuzzy Inference System Trained with Fuzzy Inclusion and Entropy Measures. Symmetry 2019, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogiatzis, A.C.; Papadopoulos, B.K. Producing fuzzy inclusion and entropy measures and their application on global image thresholding. Evol. Syst. 2018, 9, 331–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsakos, D. Introduction to Real Analysis; Afoi Kyriakidi: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baczyński, M.; Grzegorzewski, P.; Mesiar, R.; Helbin, P.; Niemyska, W. Fuzzy implications based on semicopulas. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2017, 323, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiar, R.; Kolesárová, A. Copulas and fuzzy implications. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2020, 117, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F.; Sempi, C. Principles of Copula Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, R.B. An Introduction to Copulas, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumakis, S.; Papadopoulos, B. Novel transformation of unimodal (a)symmetric possibility distributions into probability distributions. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2024, 476, 108790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baczynski, M.; Jayaram, B. (S, N)-and R-implications; a state-of-the-art survey. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2008, 159, 1836–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumakis, S.; Papadopoulos, B. An Algorithm for Fuzzy Negations Based-Intuitionistic Fuzzy Copula Aggregation Operators in Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Algorithms 2020, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xie, X. Relaxed H∞ control design of discrete-time Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy systems: A multi-samples approach. Neurocomputing 2016, 171, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Dong, J. Finite-Time Membership Function-Dependent H∞ Control for T-S Fuzzy Systems Via a Dynamic Memory Event-Triggered Mechanism. In Proceedings of the IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, Chongqing, China, 10–13 November 2023; pp. 4075–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangenakis, P.G.; Papadopoulos, B. Innovative Methods of Constructing Strict and Strong Fuzzy Negations, Fuzzy Implications and New Classes of Copulas. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, G.; Rassias, M.T.; Papadopoulos, B. Fuzzy implications based on quasi-copula and fuzzy negations. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2023, 16, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesiar, R.; Kolesárová, A. Quasi-Copulas, Copulas and Fuzzy Implicators. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2020, 13, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Lv, Y.; Li, Y.; Qian, L. Reliability Analysis of Failure-Dependent System Based on Bayesian Network and Fuzzy Inference Model. Electronics 2023, 12, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).