Abstract

Join size estimation plays a crucial role in query optimization, correlation computing, and dataset discovery. A recent study, LDPJoinSketch, has explored the application of local differential privacy (LDP) to protect the privacy of two data sources when estimating their join size. However, the utility of LDPJoinSketch remains unsatisfactory due to the significant noise introduced by perturbation under LDP. In contrast, the shuffle model of differential privacy (SDP) can offer higher utility than LDP, as it introduces randomness based on both shuffling and perturbation. Nevertheless, existing research on SDP primarily focuses on basic statistical tasks, such as frequency estimation and binary summation. There is a paucity of studies addressing queries that involve join aggregation of two private data sources. In this paper, we investigate the problem of private join size estimation in the context of the shuffle model. First, drawing inspiration from the success of sketches in summarizing data under LDP, we propose a sketch-based join size estimation algorithm, SDPJoinSketch, under SDP, which demonstrates greater utility than LDPJoinSketch. We present theoretical proofs of the privacy amplification and utility of our method. Second, we consider separating high- and low-frequency items to reduce the hash-collision error of the sketch and propose an enhanced method called SDPJoinSketch+. Unlike LDPJoinSketch, we utilize secure encryption techniques to preserve frequency properties rather than perturbing them, further enhancing utility. Extensive experiments on both real-world and synthetic datasets validate the superior utility of our methods.

MSC:

68P27

1. Introduction

With the development of big data technology and the popularization of big data analysis, it has become ubiquitous to improve the quality of service by collecting and analyzing large amounts of user data. Join size estimation, also known as inner product estimation, represents a fundamental statistical problem with applications spanning various domains, including query optimization [1,2], similarity computation [3], and dataset discovery [4]. However, collecting transaction records directly from users may reveal sensitive information, thus raising privacy concerns.

In the context of private data collection and publishing, differential privacy (DP) [5] has been proposed to provide strong, mathematically based privacy-preserving guarantees and has so far been applied to numerous areas. Specifically, without the requirement of a trusted curator, the local differential privacy (LDP) [6] mitigates privacy concerns of users by locally sanitizing private data independently on their own devices before sending them to the server. Due to its practical setup and strong privacy protection, LDP has been deployed in some popular systems, such as Apple [7], Google [8,9], and Microsoft [10]. Most existing LDP methods focus on simple statistical data analysis tasks such as frequency estimation [11,12] and heavy hitters identification [13,14], but few address complex query tasks, such as aggregation with joins. A recent work [15] has investigated the problem of join size estimation under LDP. Nevertheless, LDP imposes a large amount of noise as each user executes the randomization independently.

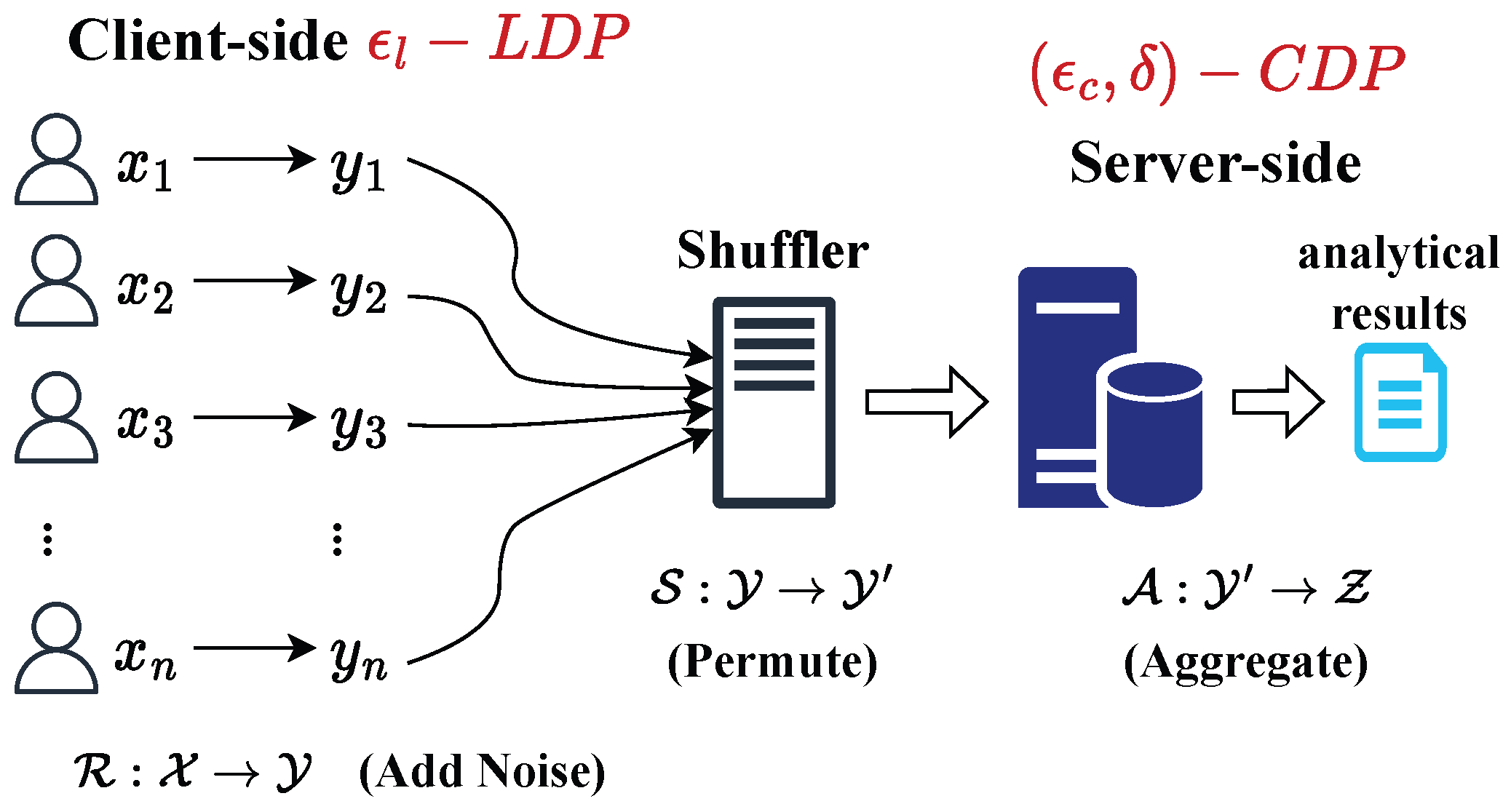

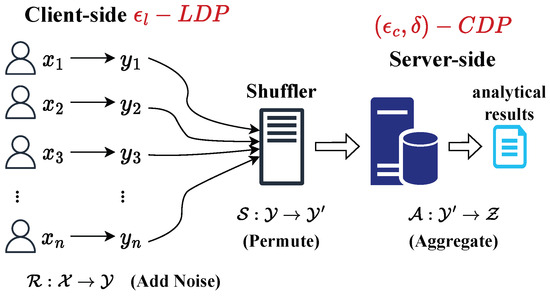

To overcome challenges regarding the accuracy of LDP and the privacy risks of centralized DP, the shuffle model of differential privacy (SDP) [16,17] has emerged. The primary change in SDP is the introduction of a semi-trusted intermediary shuffler to permute user reports. Specifically, a typical SDP setting [17] involves three main participants: a large number of users on the client side, an intermediate semi-trusted shuffler, and an untrusted third-party aggregator on the server side. The workflow can be broken down into three steps: First, each user locally encodes and perturbs their sensitive data using LDP mechanisms, then sends the randomized report to the shuffler. Next, the shuffler permutes the sanitized reports in a uniformly random order and the shuffled set of reports is then submitted to the aggregator. Finally, the server-side aggregates the perturbed reports for further specific analysis. One significant advantage of SDP over LDP is its utility. High utility means that the data under privacy protection can still effectively support original analysis tasks, such as frequency or join size estimation, with minimal accuracy loss. The permutation operation performed by the shuffler breaks the linkage between users and their reports, which brings additional privacy benefits. Consequently, less noise is required on the client side to achieve the same level of privacy (also known as privacy amplification). Although SDP has been used for data privacy protection in decentralized settings, most existing works focus mainly on basic statistics, such as binary summation [18] and frequency estimation [19]. There are few works that provide solutions for more intricate analysis tasks, such as join aggregations, under SDP.

Recent work on join size estimation under LDP introduces LDPJoinSketch [15], which utilizes sketch techniques to address the challenge of a large data domain. It constructs sketches on the server side based on perturbed values collected from individual users and then estimates the results using these sketches. Additionally, a frequency-aware protocol is proposed to reduce hash-collision errors for utility improvement. While join size estimation under LDP has been well studied, handling join aggregations with sketches under SDP remains non-trivial and presents several challenges:

1. Analyze the privacy amplification of sketch-based join size estimation under SDP: Addressing the noise error under LDP, which stems from the large domain of the join attribute, often involves utilizing probabilistic data structures such as sketches or bloom filters to reduce the domain size. However, no existing research has explored sketch-based methods under SDP, where a privacy amplification effect is introduced by the shuffler. Traditionally, this effect is mainly influenced by the number of users and the data domain. But additional parameters related to sketch size and the sampling operation increase the complexity of the analysis. We investigate this problem and redesign the protocols for private join aggregations under SDP.

2. Reduce hash-collision errors under SDP: Hash-collision errors between high- and low-frequency items in sketch construction significantly affect utility. Specifically, to reduce hash-collision errors in sketches, an intuitive idea is to separate the storage of high- and low-frequency items. However, directly sending the true frequency properties to the server would result in privacy leakage to the semi-trusted shuffler. On the other hand, perturbing this information under LDP requires partitioning the privacy budget into two parts for users’ values and their frequency properties, respectively, potentially worsening estimation utility. LDPJoinSketch avoids splitting privacy budget but instead adopts different encoding schemes for user values with different frequency properties to achieve LDP; it requires additional user partitioning to separate items with different frequency properties and still introduces some irremovable noise on the server side, resulting in utility reduction. Therefore, we need a method that allows the server to obtain the true frequency property of each received item while ensuring that the information is not leaked to the shuffler during transmission and guarantees privacy.

To enhance the utility of sketch-based join size estimation on private values, we first propose SDPJoinSketch, which allows adding less noise on the client side while maintaining the same level of privacy protection as in LDP due to the additional randomness introduced by shuffling. We provide a formal proof of privacy amplification using the privacy blanket theory [20]. Furthermore, to address the issue of hash-collision errors, we propose an improved mechanism, SDPJoinSketch+, which enables each client to be aware of its own frequency properties and adopt secure encryption techniques to encode and transmit their true frequency properties rather than adding noise through LDP. This allows the server to obtain accurate information without leaking privacy to the shuffler.

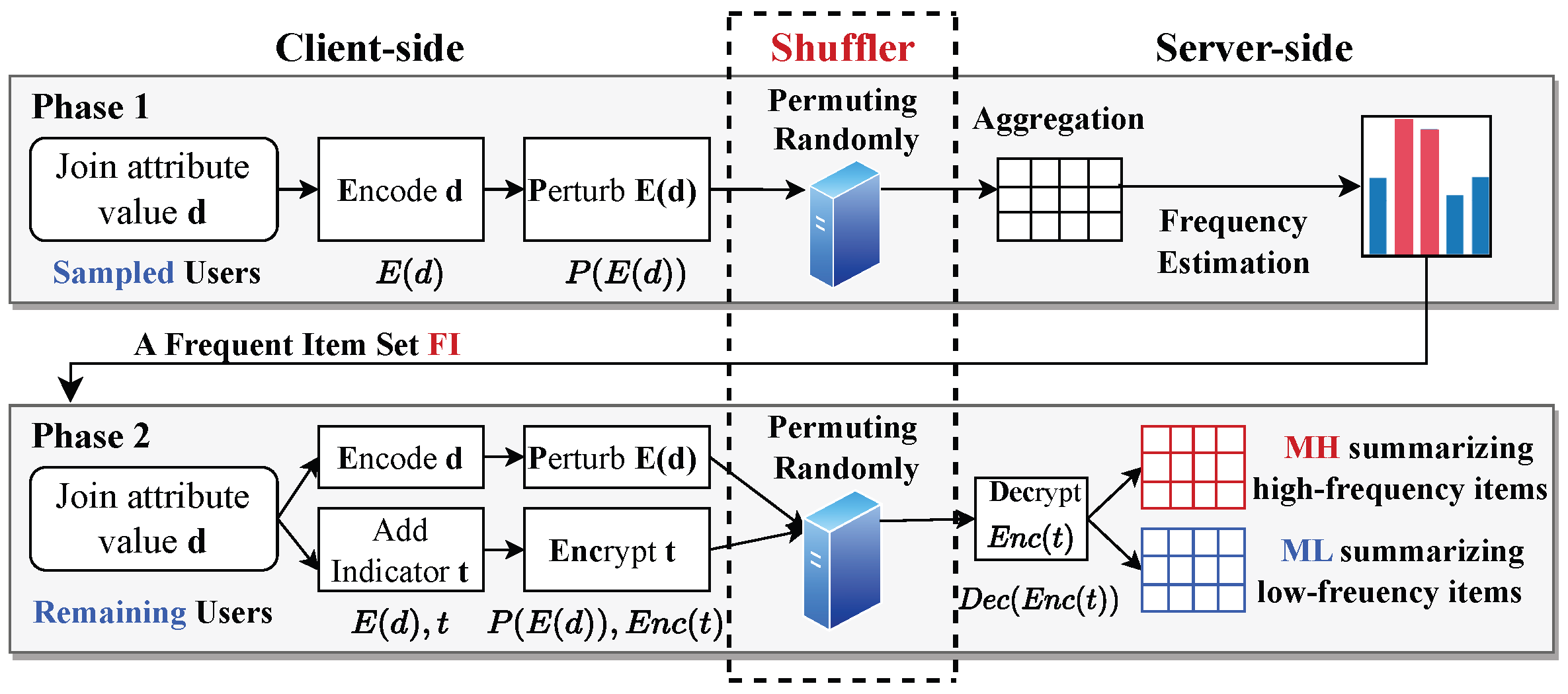

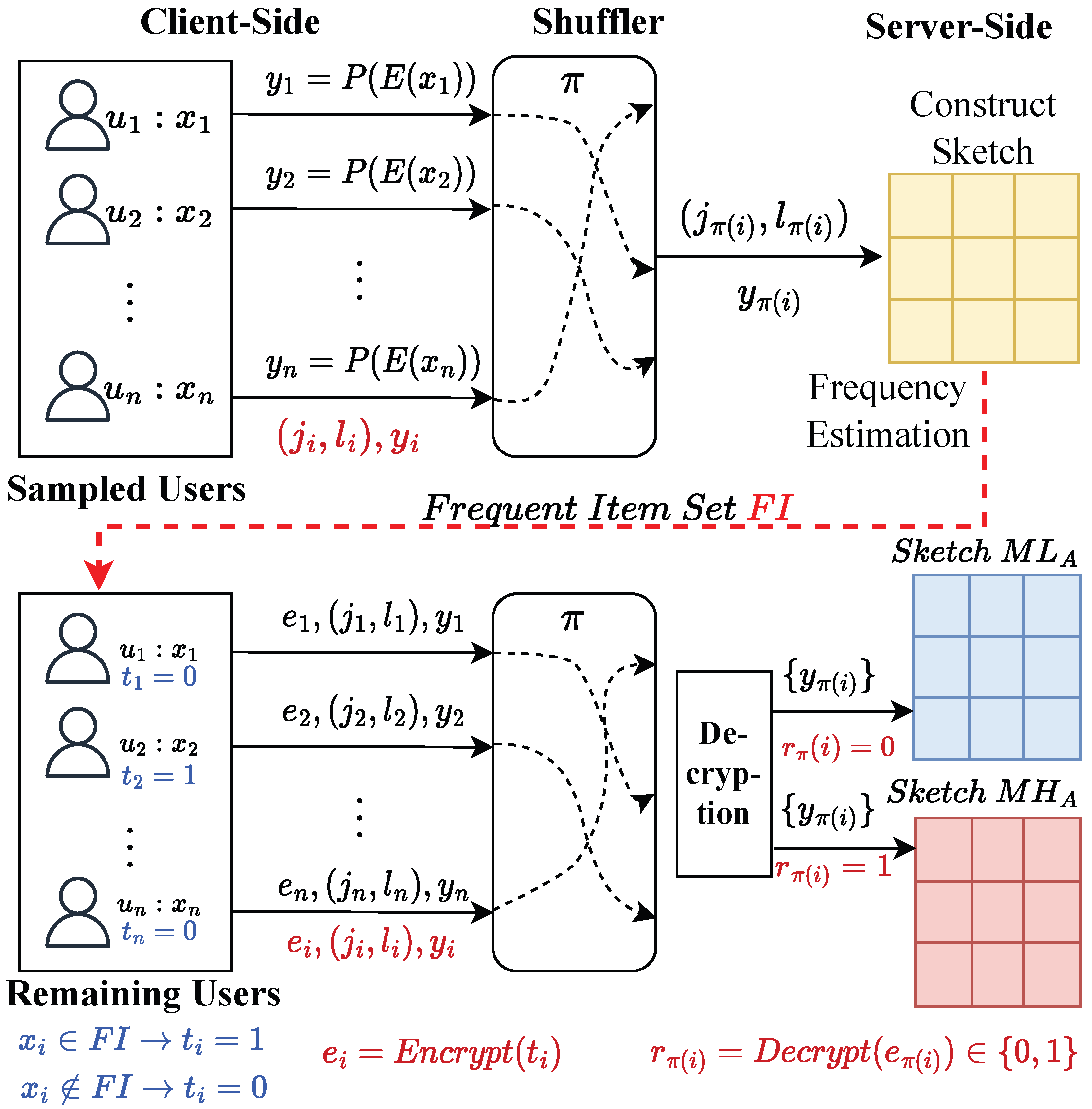

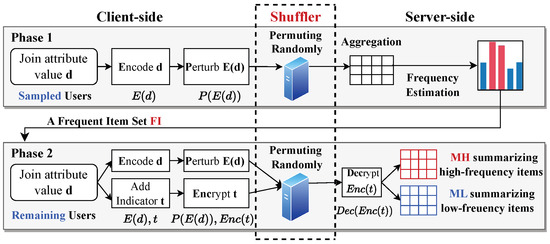

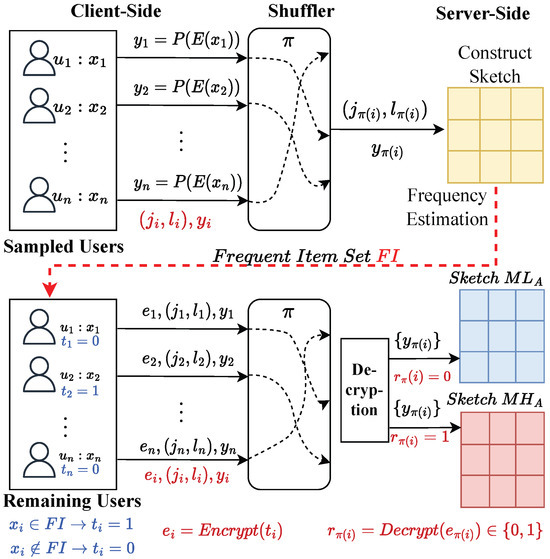

Figure 1 depicts the workflow of our proposed method, which is structured into two phases. Note that we divide the users into two groups by sampling for the tasks of the two phases, rather than directly dividing the privacy budget as in most previous works [11,15,21], since a smaller privacy budget introduces a significant amount of noise being added, thus leading to unacceptable utility. Initially, the first phase focuses on identifying frequent items among the sampled users. Each user on the client side encodes (abbreviated as ) and perturbs (abbreviated as ) their private attribute value d and submits the sanitized result to the shuffler. The shuffler then randomly permutes the reports from n users to achieve anonymization and then sends the shuffled results to the server for aggregation. The server first constructs a sketch with the permuted results and then estimates the frequencies to obtain the frequent item set () based on the sketch. The server broadcasts to the remaining users. In the second phase, the outcome from the first phase is used to differentiate between high- and low-frequency items, improving the precision of the join size estimation. Based on , an indicator t is assigned to each user, denoting whether an item is high-frequency or low-frequency. Specifically, if the private value of user i is in , then ; otherwise, . Similar to the first phase, each user encodes and perturbs d. Additionally, each user encrypts (abbreviated as ) the indicator t. Sanitized results and for each user are transmitted to the shuffler for permutation. On the server side, it separates high-frequency and low-frequency items by the decryption (abbreviated as ) results , and constructs sketches and to summarize the corresponding items.

Figure 1.

Overview of SDPJoinSketch+ (semi-trusted shuffler between clients and server).

We contend that the shuffler enhances both phases of private join size estimation. In the first phase, the presence of the shuffler improves the utility of frequency estimation while maintaining the same level of privacy guarantees. In the second phase, the shuffler disrupts the linkage between each user and their corresponding report (including both the value and its frequency property) through permutation. As a result, there is no need to perturb both the value and its frequency property separately; we can simply send the encrypted value of the true frequency property. This approach avoids the misclassification of high- and low-frequency items caused by perturbing the frequency property.

Main contributions are summarized as follows:

- We design a sketch-based protocol, SDPJoinSketch, for join size estimation under SDP. We provide detailed proof of both the privacy amplification and utility of SDPJoinSketch.

- We present an improved algorithm called SDPJoinSketch+, which reduces hash-collision errors by leveraging the anonymity of SDP with secure encryption techniques.

- We conduct experiments demonstrating the utility improvements of our methods compared to state-of-the-art approaches.

Organization. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces some related researches to this paper. Section 3 provides preliminary knowledge on join sketches and different models of DP. Section 4 shows our proposed sketch-based method for private join size estimation under SDP and its formal analysis of privacy amplification. We introduce an improved mechanism SDPJoinSketch+ which utilize the secure encryption technique to eliminate hash-collision errors in Section 5. Section 6 presents experimental results, and finally, in Section 7, we conclude the whole paper.

2. Related Work

The join size of two data streams, which represents the inner product of their frequency vectors, is a crucial metric in data stream analysis. However, due to the high time and space requirements, it is impractical and unnecessary to track the exact join size. Moreover, in scenarios involving privacy and large data domains, frequency estimation under local differential privacy tends to introduce substantial noise and is highly time-consuming. This section reviews solutions addressing the aforementioned issues.

2.1. Sketches for Join Size Estimation

As a class of streaming summaries, sketch techniques have undergone extensive development within the past few years. Sketch-based methods are among the most commonly used techniques for approximating join size [22]. The basic AGMS sketch was first proposed in [23,24], which can be viewed as a random projection of data in the frequency domain on ±1 pseudo-random vectors. The Fast-AGMS sketch [25] preserves a matrix of basic AGMS counters to improve accuracy and efficiency simultaneously and achieves the best performance. To reduce hash-collision errors, the Red sketch [26] and the Skimmed sketch [27] propose to estimate the join size by separately estimating the inner product of high-frequency items and low-frequency items. JoinSketch [28] further improves the estimation accuracy, particularly in cases where the data is highly skewed. However, these studies do not address scenarios where the join attribute values involve user privacy. In the field of multi-party secure computation (MPC), Google’s Private-Join-and-Compute (PJC) [29] protocol combines private set intersection with homomorphic encryption to enable cross-organizational precise computation of join size without compromising privacy. However, it incurs high communication and computational overhead.

In recent years, several differentially private sketch techniques [7,30,31] have been introduced for conventional statistical tasks. More recently, the LDPJoinSketch [15] has been proposed to achieve high estimation accuracy while preserving individual privacy in an LDP setting for private join size estimation. But due to the nature of LDP, the level of noise required per user is extremely high, which limits its efficacy. Building on this study, we extend the task to the shuffler setting to tackle the utility issue.

2.2. Techniques and Applications Under SDP

To mitigate the high noise required in LDP, recent work has proposed SDP, where a semi-trusted shuffler is introduced to obscure individual private views within the crowd. The shuffling idea was originally presented in Prochlo [32]. The Encode, Shuffle, Analyze (ESA) model in Prochlo provides a general framework for incorporating a shuffling step in private protocols. Later work [17] demonstrated that the introduction of a secure shuffler amplifies the privacy guarantees. SDP was formally defined in [16] and it derives a similar conclusion for binary randomized response messages. Balle et al. [20] further improved the amplification results and introduced the idea of a privacy blanket whose main idea is to decompose the probability distribution of an LDP report into two distributions and mask the truthfully reported outputs. This technique provides the strongest amplification result and its proof method can be applied to other LDP protocols. We incorporate this idea into our protocol design and privacy amplification analysis.

Some recent works utilize SDP to achieve a better privacy–utility trade-off for specific analytical tasks. For frequency estimation tasks, Hist_KR [20] applies a basic random response mechanism within the ESA framework. It is the simplest and most direct method in frequency estimation. To further enhance utility, SLH [33] achieves an error that is independent of domain size, making it suitable for cases with large domains. Ghazi et al. [34] introduced a protocol in the SDP model for estimating the sum or mean of real- or integer-valued data, achieving error rates comparable to CDP. Wang et al. [35] proposed the SDPKV method, which integrates key-value perturbation with privacy budget amplification analysis under the SDP model, significantly improving the accuracy of key-value data collection. In addition, mechanisms [36,37] based on multi-message shuffle model achieve a smaller error compared to the previous methods. Nevertheless, existing research has not yet explored more complex statistical queries, such as join aggregations.

3. Preliminaries

We give the formal problem definition of sketch-based join size estimation. And we retrospectively examine the definition of differential privacy in the centralized, local, and shuffle models. We list commonly used notations of this paper in Table 1.

Table 1.

The notations of symbols.

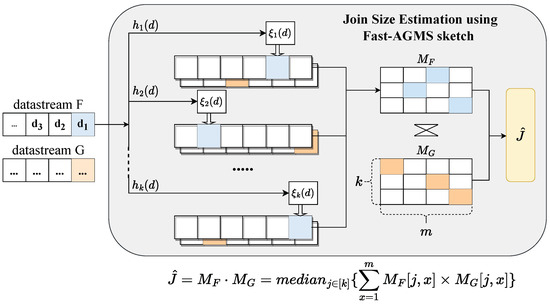

3.1. Fast-AGMS

We let F be a data stream with private join attribute values from n users. We use to represent a data item in a data stream. We assume D is the domain of all items and . For the data stream F, we define the frequency vector where represents the frequency of the tth item in domain D. Similarly, we can derive the frequency vector of another data stream G and . The inner product of two data streams F and G is defined as , which is equivalent to the join size.

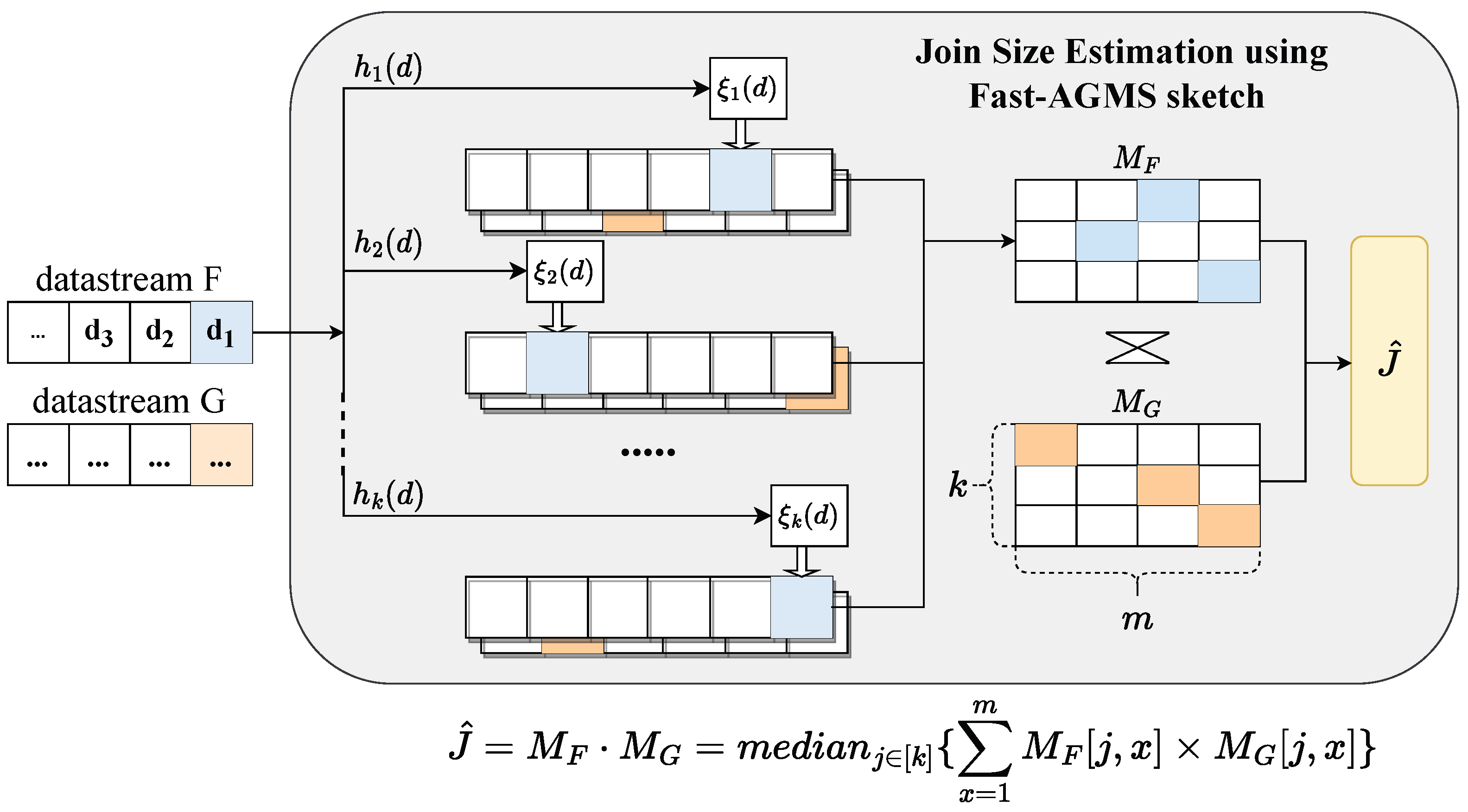

The Fast-AGMS sketch is one of the typical sketches for join size estimation. A Fast-AGMS sketch [25] consists of an array of m counters. Besides the random function used in the basic AGMS sketch, another hash function h is introduced to map an item to a random counter. Based on the Fast-AGMS sketch, the join size estimation of F and G is the summation of the product of corresponding counters of the two Fast-AGMS sketches and :

where m is the number of counters in a Fast-AGMS sketch.

The Fast-AGMS scheme is shown in Figure 2. Researches usually use the median estimation of multiple Fast-AGMS sketches to improve accuracy. The estimation can be written as

where are the number of lines and columns of a sketch. Intuitively, the estimation accuracy improves as the value of m increases due to lesser hash-collision probability.

Figure 2.

Fast-AGMS sketch for join size estimation.

3.2. Centralized Differential Privacy (CDP)

Differential privacy (DP) [5] is a rigorous notion about an individual’s privacy. In the centralized model of DP (abbreviated as CDP), there is a trusted data curator obtaining raw data from all users and introducing proper mechanisms adding noises to the statistical results for preserving privacy.

Definition 1.

(-differential privacy (-DP) [5]). A randomized algorithm satisfies -DP, where , if and only if for any neighboring datasets and , :

where the privacy budget ϵ indicates the degree of privacy protection. A smaller ϵ indicates a stronger privacy guarantee but lower data utility.

3.3. Local Differential Privacy (LDP)

In the local model of DP (abbreviated as LDP), each user independently perturbs their input by using a local randomizer.

Definition 2.

(-local differential privacy (-LDP) [6]). A randomized algorithm R is ϵ-locally differentially private if for any pair of different inputs t and , :

The local model removes the requirement for a trusted curator, resulting in a higher level of noise per user to be tolerated to achieve the same privacy guarantee.

3.4. Shuffle Model of DP (SDP)

In the shuffle model of DP (abbreviated as SDP), a semi-trusted shuffler is deployed as an intermediary component between the clients and the server. The shuffler collects perturbed reports from multiple clients, applies a random permutation, and forwards the shuffled results to the server. We use to denote the protocol of SDP. Here, denotes the local randomizer with privacy budget , and denotes the shuffling procedure. The privacy goal of the shuffle model is to ensure the shuffled messages satisfy -DP for all neighboring datasets, where denotes the amplified privacy level.

Definition 3.

(-DP in the shuffle model [16,17]). A protocol is -DP if, for any neighboring datasets ,, the mechanism satisfies -DP.

In SDP, the privacy of protocol is a property of the entire set of n users’ reports, and the data collector only observes the shuffled results while obtaining no information about the linkage between the users and their reports.

Summary of CDP, LDP and SDP. These three DP models present a trade-off between privacy and utility. In terms of reliance on a trusted third party, LDP has the smallest trust assumption. And in terms of utility, CDP offers the highest result accuracy. Overall, the SDP falls between LDP and CDP in both aspects, striking a better balance between the privacy and utility.

Lemma 1.

From , the probability of computing tag ’s or the current session key maintained in is negligible.

Proof.

The messages in that do not involve or do not give any advantage in obtaining these keys. Here, is used in the form of and is used in the form of , , and . By Lemma 1, even if adversaries obtain many values of these forms, it is computationally infeasible to obtain . As a result, when the length of and is both , the probability of computing one of these keys is . If is sufficiently long, this is negligible. Therefore, this lemma holds. □

4. Sketch-Based Join Size Estimation Under SDP

In this section, we introduce a sketch-based join size estimation protocol under SDP (SDPJoinSketch) and give theoretical proof of the privacy amplification after shuffling.

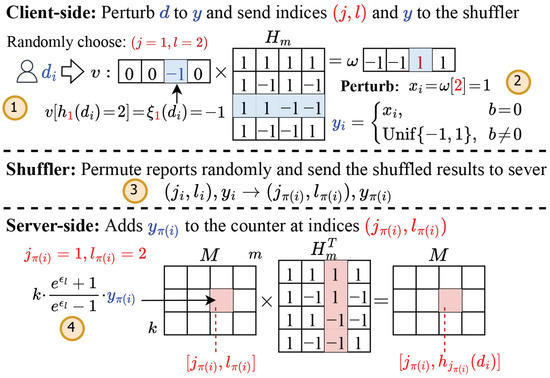

4.1. SDPJoinSketch

We aim to design a protocol under SDP for join size estimation, which can achieve better utility than methods under LDP. The main idea of our proposed protocol is to utilize a semi-trusted shuffler to permute the sanitized reports, which consist of the indices and perturbed values of each individual from all users. This approach breaks the linkage between users and their reports, thus providing privacy benefits compared to solely using the LDP model. In other words, our protocol can provide the same level of privacy guarantee while requiring less noise addition than LDP. Consequently, the estimation utility on the server side is improved.

4.1.1. Client Side of SDPJoinSketch

The client side of SDPJoinSketch has two main tasks, which include encoding the private attribute values of users and then perturbing the encoded results with LDP mechanisms. Finally, for each user, it sends a triplet including a perturbed value and the corresponding indices of the counter in the sketch.

The pseudo-code of the local randomizer is illustrated in Algorithm 1. Given a private join attribute value from the ith user and the hash function pairs for sketch construction, and . The client side first encodes the value (Lines 3–5). The algorithm samples a line index j and a column index l uniformly at random from and , respectively. A m-length zero vector v is initialized to record the hash result of value , i.e., the position of v is then encoded into . Inspired by the idea in [7], the algorithm leverages the Hadamard basis transform to decrease the communication cost that it generates for vector v, , and only chooses the single bit to be further privatized. After encoding, the algorithm perturbs it with randomized response technique (Lines 6–11). Specifically, it first samples a value b from a Bernoulli distribution , where with probability and with probability . And if , the encoding value remains unchanged, i.e., . Otherwise, if , the algorithm uniformly at random chooses a value from .

| Algorithm 1 Local Randomizer |

| Public Parameters: |

| Input: Local data from i-th user, Hash function pairs |

| Output: indices and perturbed data |

| 1: Sample uniformly at random from [k] and [m], respectively. |

| 2: Initialize a vector |

| 3: ▹Encode (Lines 3–5) |

| 4: ▹ is a hadamard matrix of order m |

| 5: |

| 6: Sample ▹ Perturb (Lines 6–11) |

| 7: if then |

| 8: |

| 9: else |

| 10: Unif({−1,+1}) |

| 11: end if |

| 12: return |

Theorem 1.

The local randomizer of SDPJoinSketch satisfies -LDP.

Proof.

Since the indices are sampled uniformly at random, we show for an arbitrary output that the probability of observing the output is similar whether the user reported data d or . We suppose the encodings of d and are v and , respectively, and the differences between v and are on two bits, i.e., and . We let J and L be the random variables selected uniformly from and , respectively. And B is the random variable for the random bit b. Here, , . We simplify as R, and therefore

where we slightly abuse the notion and use Uni(2) for Unif({−1,+1}) and , , the samples from hadamard transform , . We assume the encodings of two different inputs d and are different, i.e., and . Without loss of generality, when , the maximum probability for input d to obtain is and for input to obtain is . We have

Similarly, we can derive that . Thus, the local randomizer of SDPJoinSketch satisfies -LDP. □

In summary, the client still satisfies LDP, reducing reliance on trusted curator and fostering greater trust in the model of SDPJoinSketch.

4.1.2. Intermediate Shuffler of SDPJoinSketch

In the shuffling process, we aim to shuffle the sanitized reports from all users in a random permutation and then output a shuffled set , where represents the shuffling result of index i, to achieve anonymity, which can result in a higher level of privacy protection on the server side. Particularly, we adopt the Fisher–Yates random permutation algorithm [38] for shuffling. The algorithm effectively permutes the inputs by iterating through the elements from the last to the first, swapping each element with another randomly selected element that comes before it. The shuffling process ensures that every permutation of the inputs is equally likely with probability,

This result makes the shuffle unbiased, which is a essential property for the subsequent analysis of privacy amplification.

4.1.3. Server Side of SDPJoinSketch

In the context of private join size estimation, the server has two tasks. One is to collect shuffled reports from the shuffler and construct sketches. Another is to estimate join size using these sketches.

The pseudo-code of the analyzer is illustrated in Algorithm 2. The server side observes a multi-set generated from the shuffler and has no information about the linkage between each massage and the user. For the task of sketch aggregation (SKA), the server aims to construct an SDPJoinSketch with all randomized reports. First, an empty sketch M of size is initialized (SKA, line 1). For each report in , it multiplies with k and for debiasing and then adds it to the sketch M at position (SKA, Lines 2–4). After inserting all items into sketch, sketch M is calibrated by multiplying the hadamard matrix to recover information (SKA, Line 5). For the task of join size estimation (JSE), it takes two SDPJoinSketch and as input. It computes the inner product of each row from and (JSE, Lines 1–6) and takes the median of all k results as the final output (JSE, Lines 7–8). We analyze the utility of the estimator under SDP in Section 4.3. To clarify the protocols illustrated above, we provide a concrete example for further explanation.

| Algorithm 2 Analyzer |

| Public Parameters: |

| ⊳ Sketch Aggregation: (SKA) |

| Input: Multi-set |

| Output: Private Sketch M |

| 1: Initialize a sketch |

| 2: for do |

| 3: |

| 4: end for |

| 5: |

| 6: return M |

| ⊳ Join Size Estimation (JSE): |

| Input: Private Sketches and for user groups A and B |

| Output: Join Size Estimation |

| 1: Initialize a vector |

| 2: for do |

| 3: for do |

| 4: |

| 5: end for |

| 6: end for |

| 7: |

| 8: return |

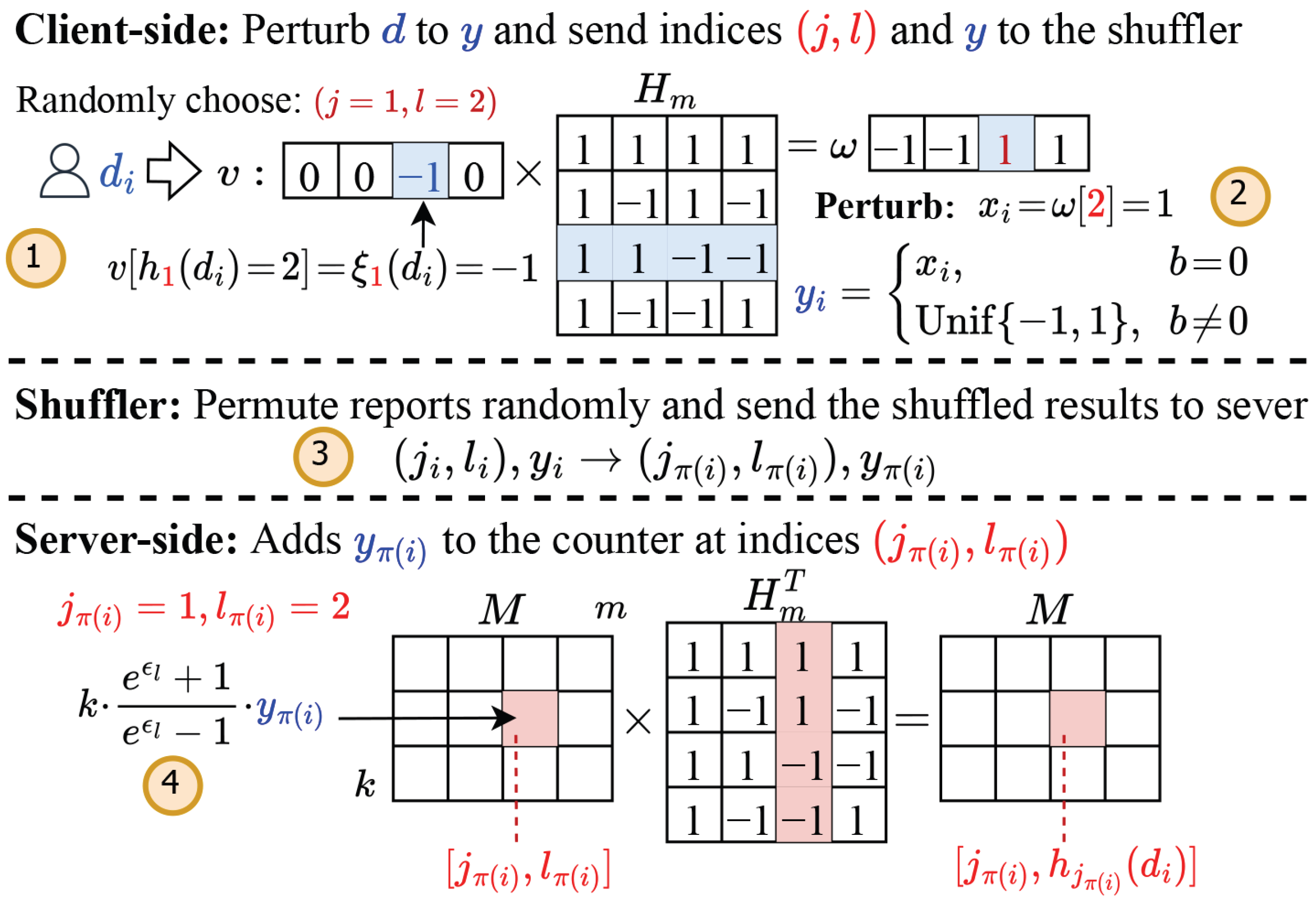

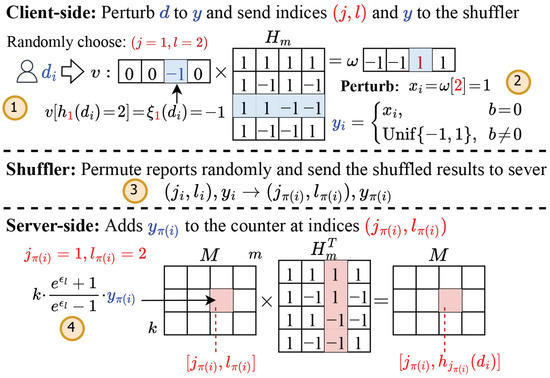

Example 1.

We use an example in Figure 3 to show the workflow of SDPJoinSketch. Here, public sketch parameters are , . denotes the private value of the ith user. Suppose the indices are sampled randomly as and , with the corresponding mapping results of the hash function pairs given by and . ①

Each client

encodes to a m-length one-hot vector where , and then transforms v to a single bit by multiplying it with a hadamard matrix and taking the value of l- bit. ② is then perturbed to based on the value of b, which is sampled from a Bernoulli distribution. Finally, the client sends to the shuffler. ③ After the shuffler

receives the reports from all n users, the shuffler—functioning as an independent component between clients and the server—randomly permutes the data and sends the shuffled results to the server. Notice that at this point, the intrinsic association between each report and its respective users has been severed. ④

The server

constructs a sketch M by adding each multiplied with and a scale factor to the sketch at indices for debias.

Figure 3.

Example of SDPJoinSketch (semi-trusted shuffler between clients and server).

We can learn from the example that after being permuted by the shuffler, the server loses the association between the user and the report, i.e., i to , since is a random shuffling operation. Therefore, the aggregated sketch on the server side achieves privacy amplification due to the addition of this extra randomness.

4.2. Privacy Amplification via Shuffling

As previously mentioned, the shuffler can break the linkage between the report and the user identification to further obtain some privacy benefits, since more randomness is introduced. Specifically, the server side observes a higher level of privacy protection (i.e., -CDP) after shuffling compared with the situation where only the LDP model (i.e., -LDP) is implemented, as shown in Figure 4. So the privacy amplification can be presented as the change in to , where . Equivalently speaking, to measure the utility improvement rather than privacy amplification, we could fix the overall privacy guarantee on the server side to derive the needed on the client side. Therefore, with the same level of centralized privacy guarantee, less noise is required on the client side when shuffling is used, leading to higher utility. In this subsection, we provide the quantitative results of privacy amplification for SDPJoinSketch.

Figure 4.

Framework of SDP (semi-trusted shuffler between clients and server).

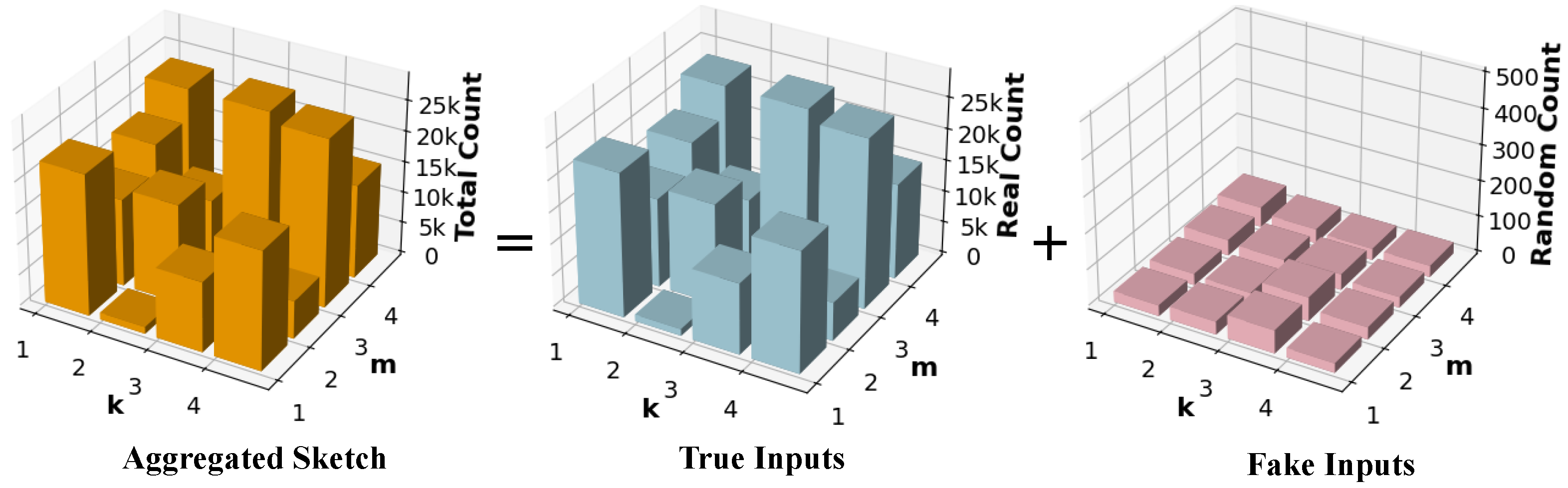

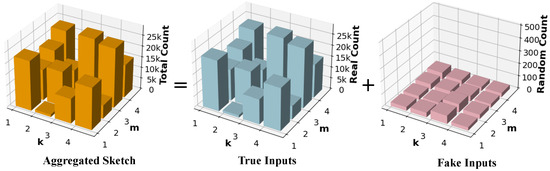

In our SDPJoinSketch mechanism, we encode the value into binary form with private view domain . As shown in Figure 5, the final sketch aggregated on the server side consists of two parts based on the privacy blanket theory [20]. One is constructed by true reports (the blue sketch) while another is constructed by fake reports (the pink sketch) from uniformly random values. In the context of CDP, the private information of the target user can obscured by the sketch with independent random inputs (the pink sketch). To achieve differential privacy, the aggregated sketch changes by an appropriately bounded amount when computed on neighboring datasets where only a certain user’s input changes, and this user can response truthfully or randomly. Since the privacy argument does not rely on the anonymity of random fake inputs, we focus on the scenario where the target user uploads the true value. Suppose the number of users is n and the nth user responses truthfully, through Algorithm 1; about users respond uniform randomly. They contribute binomial random noise to each frequency of , where the binomial random noise refers to the noise arising from the sum of independent randomized responses from multiple users, which follows a binomial distribution in aggregation. Based on the Binomial Mechanism proposed in [33], we present the formal privacy guarantee of SDPJoinSketch in Theorem 2.

Figure 5.

Sketch decomposition under SDP.

Theorem 2.

Given the local randomizer R for SDPJoinSketch, after shuffling, the mechanism satisfies , where

Proof.

We assume D and are neighboring datasets and differ in the item of the nth user, i.e., . From randomizer and shuffler, the outputs of all users are where . We use E to present the encoding step of item and it is related to the hash function pair and randomness of hadamard transform (i.e., the selection of , which equals to ). To prove satisfies , it is suffice to prove that

where Z denotes the output of mechanism on dataset D.

We divide the proof of Equation (8) into four steps. We assume that the attacker has maximum background knowledge, which means they know the true inputs of all users except the target user (the nth user for simplicity). We first start with the input of the nth user. To analyze whether the changes in the aggregated sketch can be bounded on two neighboring datasets differing on the inputs of the nth user for the requirement of differential privacy, we consider two cases based on previous discussion. Then, we decompose the aggregated sketch on the server side into three parts to facilitate the analysis of probabilities. Next, we compute the ratio of probabilities according to binomial mechanism and finally impose constraints on the result to derive upper bound of the amplified privacy budget.

Step 1. Analyze the above inequality in two cases based on the response of the nth user.

We assume that the encodings and . Case 1: The nth user in both D and submits a random value. Considering the case that the nth user in both D and submits a random value from with probability , the privacy holds trivially since . Case 2: The nth user in D and submits the true value, respectively. We focus on the case where user n responses truthfully with probability . According to the shuffle algorithm, there are different permutations in the Fisher–Yates shuffle of messages from n users. We can examine the probability after perturbing and shuffling on D:

Here, denotes the output probability under a specific permutation .

Step 2. Expand the expression of output probability based on the reports from different kinds of users.

Inspired by the idea of privacy blanket [20], we can expand the probability into three parts, including the probability of reports from the users who respond truthfully among the first users, of reports from users who respond randomly among the first users, and of the report from user n. The probability is expanded to

We let represent the probability that user i chooses encoding indices , where and .Therefore,

where the indicator function means that the report from the user in T matches the permuted report. If equals to , then ; otherwise, it is 0. Intuitively, the probabilities and are independent of . And the probability for user n can be analyzed as follows:

After we derive the output probabilities of different parts of users, we can combine them to determine the total output probability under permutation .

Step 3. Compute the ration of output probabilities on neighboring datasets with binomial random variables.

First, since is a constant independent of and , we can simplify the fraction. Thus,

where is the number of reports received by the server with value except the truthful answers from the first users, i.e., , which follows a binomial distribution . Similarly, follows a binomial distribution . Following this result, we simplify the left part of Equation (8):

According to expectation of binomial distribution, we let . Based on Chebyshev’s inequality, implies that either or .

Step 4. Bound the ration of binomials with union bound and Chernoff bounds, thus deriving the upper bound of .

We first bound the probability of the ratio of binomials and with a union bound that . Then, leveraging the Chernoff bound, we have

Combining these results, the probability in Equation (16) can be bounded:

Assuming , to ensure the overall result is less than , each term on the right side of the inequality should be less than or equal to , i.e., and . Since , we can derive that

The probability ration is bounded, and the mechanism satisfies -CDP. □

In this subsection, we give the formal analysis of the privacy amplification of SDPJoinSketch that a lower privacy level of LDP on the client side can result a higher privacy level of CDP on the server side. Therefore, we can derive from a fixed , i.e., and .

4.3. Utility Analysis

Here, we analyze the utility of our proposed method. In particular, to analyze the accuracy of join size estimation, we measure the variance of the estimator, i.e.,

where k and m are the number of lines and columns of a sketch.

Fixing the local , the variance has already been derived under LDP. We restate the result and extend it to SDP.

Lemma 2

([15]). Given the sketch size and the LDP parameter , the variance for an estimator under LDP is bounded up to , where , and represent the total number of users for attribute A and attribute B, respectively.

Based on the lemma, we derive the variance of SDPJoinSketch. To ensure the privacy level of the two join attribute values is the same on the server side, we fix the and compute and on the client side, respectively.

Theorem 3.

Given centralized privacy budget in the shuffler model, we denote and as the amplified result on the client side for SDPJoinSketches and . Thus, the variance of shuffle model is bounded by , where , .

Proof.

From Theorem 2, we have and . Since the privacy benefits are related to the number of users in data stream, the amplification results for and are different. Plugging them in Lemma 2, the variance is , where , . □

Intuitively, SDPJoinSketch has a lower variance bound compared to the conventional LDP setting due to the larger privacy budget on the client side.

5. Improving Utility of SDPJoinSketch

In this section, we design protocols to improve utility of SDPJoinSketch by reducing hash-collision errors of the sketch under SDP.

5.1. Framework of SDPJoinSketch+

In the scenarios of real data, the estimation accuracy of SDPJoinSketch is usually poor because the real data often obey unbalanced distribution and are highly skewed. When constructing the sketch, the hash-collision errors are mainly introduced by the collision between high-frequency items and low-frequency items, since the probability of collisions between high-frequency items is so small that it can be ignored. Inspired by this conclusion, we can enable users to upload precise information about whether they possess high-frequency items. Nevertheless, two issues still need to be addressed. As we discussed earlier, the link between sanitized reports and individual users is broken, allowing us to preserve the true frequency property and the corresponding sanitized report to the server side. However, each client-side user has no idea whether their item is high-frequency or low-frequency. Furthermore, neither the true frequency property nor the true value can be disclosed to the semi-trusted shuffler.

To address the first issue, we propose a two-phase framework SDPJoinSketch+, which identifies high-frequency items in the first phase as a prior knowledge to help the frequency property identification in the second phase. In both of the phases, users’ true item values are protected through DP noise addition, which still satisfies the constraints of SDP. For the second issue, we leverage a secure encryption technique to achieve this goal. Specifically, in addition to transmitting the sanitized reports by SDP, users also encrypt and transmit the true frequency properties obtained from the first phase. There are two motivations. One is that partitioning the privacy budget for the protection of frequency properties introduces more noise into the item value perturbation, resulting in low utility. Another is that the advantage of the shuffle model has not been fully utilized, as we can allow the server side to obtain the true frequency property of each report while ensuring the privacy guarantee of user data, since the linkage between reports and users is disrupted by the intermediate shuffler.

The framework of SDPJoinSketch+ is shown in Figure 6. The main idea of this improved framework is that we identify the high-frequency item set through a group of sampled users in the first phase by frequency estimation. And then the server broadcasts this set to remaining users so that each user can identify whether its data are high-frequency or low-frequency.

Figure 6.

Framework of SDPJoinSketch+.

In terms of results, an indicator is introduced on the client side which we denote as where if the sensitive data of user i are in and if not. Since the value of is also sensitive information, we need to handle it with privacy-preserving techniques. Instead of using differential privacy which causes utility reduction, we leverage secure encryption techniques, such as symmetric encryption, to protect . Each user encrypts its to obtain and submits it to the shuffler with LDP reports, i.e., . After receiving reports from n users, the shuffler uniform-randomly permutes them and handles the set to the server. On the server side, it first decrypts the of every report, i.e., , thus acquiring the knowledge of whether this item is high-frequent but having no idea of which user it belongs to. Through this method, we can effectively separate high- and low-frequency items in the report while preserving privacy.

The pseudo-code is illustrated in Algorithm 3. In Stage 1, we aim to find the frequent item set based on the sampled user subsets and for attributes A and B. The server constructs sketches , using the perturbed and shuffled reports from two subsets (Line 1–2).

Then, we can obtain the frequency item set (Line 3) through , whose pseudo-code is shown in Algorithm 4. The server side first estimates the frequency vector based on SDPJoinSketch (, Line 1–7) and then finds the high-frequency items whose frequency estimates are larger than the threshold (, Line 8–15). The server broadcasts this set to each user client. In Stage 2, the client side adds indicators t for each user to identify whether its item is high-frequency or not and encrypts the indicator (Line 1–5). It then perturbs data from remaining users and sends them to the shuffler (Line 6–7). After receiving the shuffled messages, the server first decrypts each to . So the shuffled messages can be divided into two parts, which are used for high-frequency and low-frequency sketch construction, respectively (Line 10–11). We use the in Algorithm 2 to estimate the join size for low-frequency items and high-frequency items (Line 12–13). Finally, we compute the overall join size by scale the sum of and with factor (Line 14), where the notion denotes the total number of users in a subset.

| Algorithm 3 SDPJoinSketch+ |

| Public Parameters: |

| ⊳ Stage 1: Find frequent join values |

| Input: Sampled subsets |

| Output: Frequent Item set |

| 1: Clients: Perturb data from with Algorithm 1 |

| 2: Server: Construct SDPJoinSketch and |

| 3: Frequent item set |

| 4: return |

| ⊳ Stage 2: Improved join size estimation |

| Input: Remaining subsets , and |

| Output: Join Size Estimation |

| 1: Clients: add indicator t for each user. |

| 2: for and do |

| 3: if , else |

| 4: |

| 5: end for |

| 6: Perturb data from and with Algorithm 1 |

| 7: Return |

| 8: Shuffler: |

| 9: Server: |

| 10: Construct sketches , with |

| 11: Construct sketches , with |

| 12: in Algorithm 2 |

| 13: in Algorithm 2 |

| 14: |

| 15: return |

| Algorithm 4 FFI: Find Frequent Items |

| Public Parameters: , frequent threshold |

| Input: SDPJoinSketch |

| Output: Frequency item set |

| 1: Initialize |

| 2: for do ▹ Estimating frequency |

| 3: for do |

| 4: |

| 5: end for |

| 6: |

| 7: end for |

| 8: ▹ Threshold for high-frequency item |

| 9: Initialize |

| 10: for do |

| 11: if then |

| 12: Add d into |

| 13: end if |

| 14: end for |

| 15: return |

5.2. Privacy and Utility Analysis

User size n is a critical parameter in the shuffle model. Since in SDPJoinSketch+ we divide the users into two groups of different sizes for separate goals, the privacy amplification results of the two phases are different.

Theorem 4.

Given the sample rate r and local privacy budget , , Phase 1 of SDPJoinSketch+ satisfies and Phase 2 of SDPJoinSketch+ satisfies , where r is the sampling rate.

Proof.

Similar to the proof of Theorem 2. Note that the number of users is different in the two phases, thus leading to different privacy amplification results. □

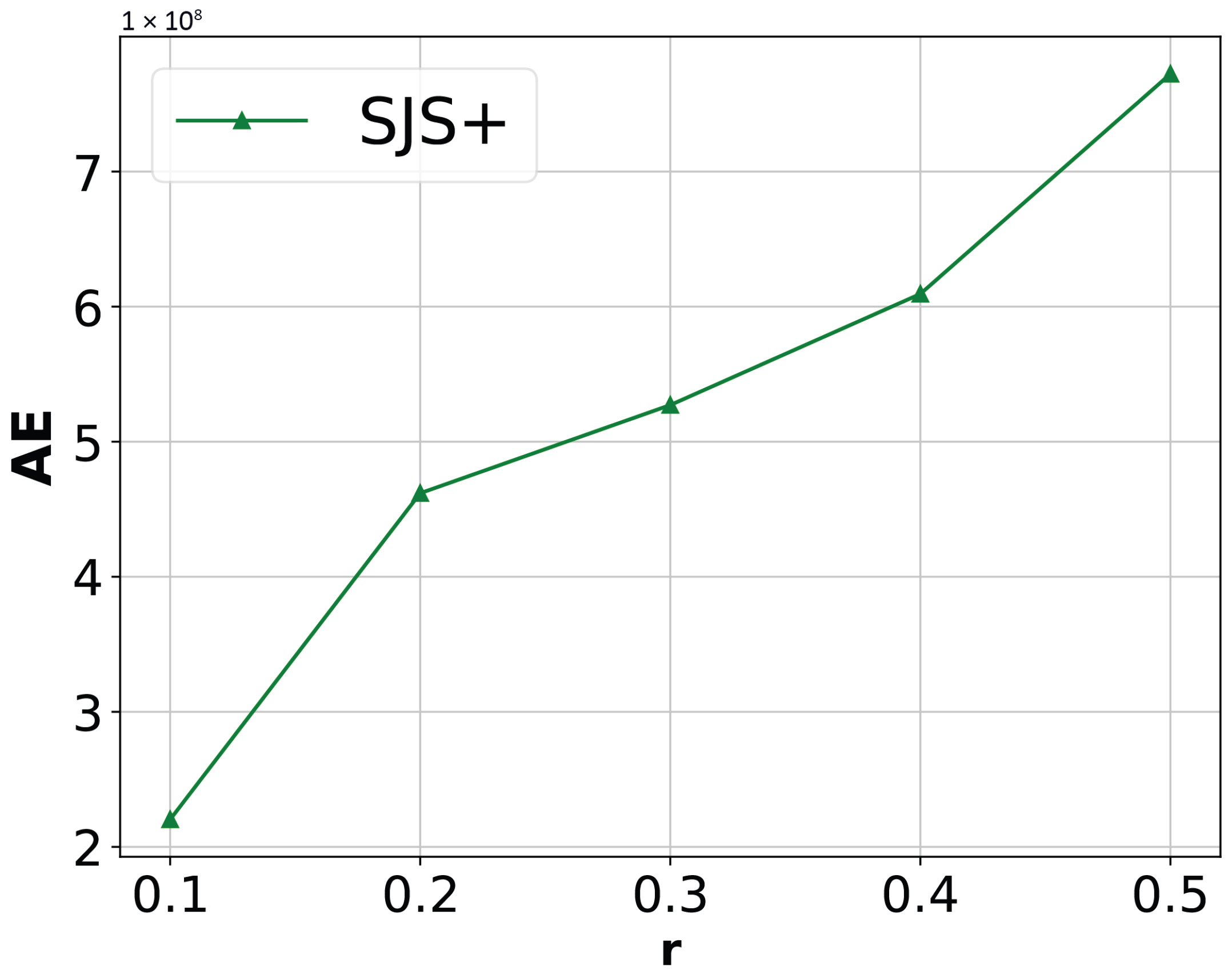

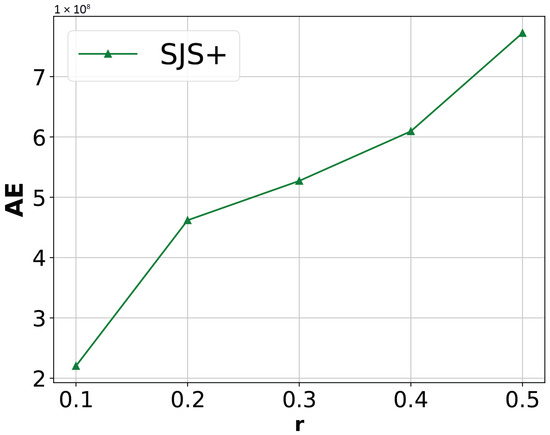

The privacy result shows that when sampling rate r decreases, the first phase brings greater privacy benefits thus obtaining more accurate result of frequency estimation. On the other hand, the join size estimation based on remaining users in the second phase acquires worse utility. However, in SDPJoinSketch+, we only need the frequent items set rather than accurate frequencies. Even when the amplified is small, we can use approximate frequency estimation to identify heavy hitters, especially in highly skewed data. Overall, the utility of SDPJoinSketch+ may become worse when the sampling rate increases, and our experimental results in Section 6.2 also confirm this conclusion.

For simplicity, we assume that frequent item set obtained from Algorithm 4 is sufficiently accurate. In practice, this assumption has been validated through preliminary experiments: SDPJoinSketch+ achieves over accuracy in identifying the during Phase 1, which is consistent with the experimental results presented in Section 6.2. Therefore, the final estimation result of SDPJoinSketch+ depends only on the sampling rate and estimation from high-frequency and low-frequency items in the second phase. We give the error bound as follows.

Theorem 5.

Given the sketch size parameters , sampling rate r, and centralized privacy budget in the shuffler model, we denote and as the local privacy budgets on the client side for the remaining users of data streams A and B, respectively, due to the privacy amplification effect. Assuming the proportion of users holding high-frequency items is μ, the variance for a join size estimation of SDPJoinSketch+ in Algorithm 3 is limited, i.e., , where and .

Proof.

Similar to the proof of Theorem 3. But there are two main differences. First, the local privacy budgets vary with the change in user numbers by sampling due to the privacy amplification effect. Second, since the construction of sketches for high-frequency items and low-frequency items are independent, the variance of join size estimation results can be derived as the summation of and , which can be easily calculated based on Theorem 3. □

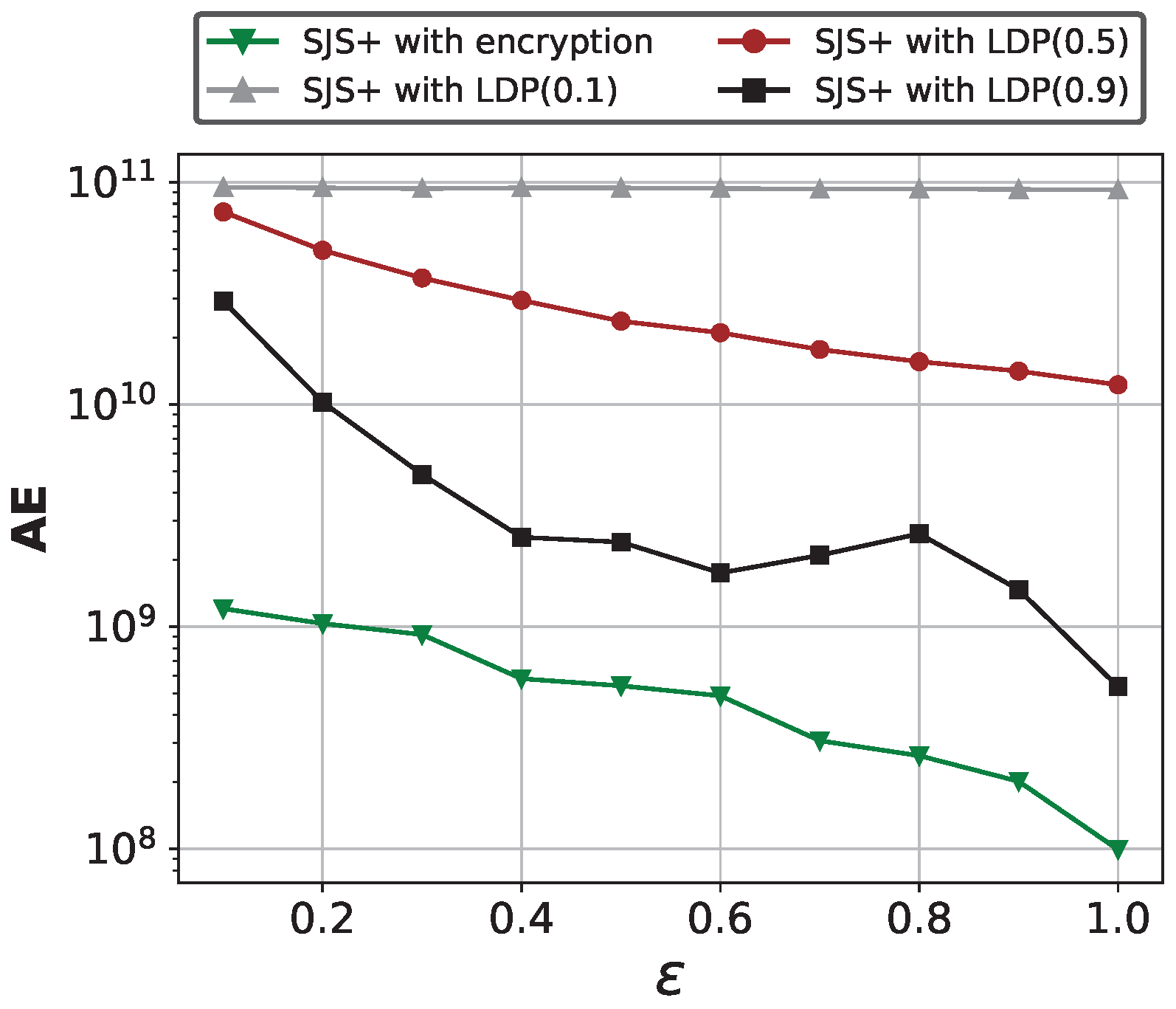

The secure encryption techniques used in the second phase can prevent the privacy leakage from the shuffler, and the server can obtain accurate frequency information of the sanitized and anonymized reports. However, the frequency properties are not under the protection of differential privacy since the malicious users still can infer whether the item of an individual in the remaining users is frequent or infrequent by differential attacks. A simple way to address this issue is dividing the privacy budget and adding random noise into the frequency property indicators, but it significantly reduces utility. The experimental results of comparison between encryption and LDP perturbation in Section 6.2 validate this inference.

Moreover, our method can be easily extended to multi-way join scenarios. This is similar to LDPJoinSketch [15], with the difference being the need to analyze the privacy amplification effect when multiple parties are involved.

6. Experimental Evaluation

In this section, we mainly evaluate the utility of our proposed methods SDPJoinSketch and SDPJoinSketch+ for private join size estimation on both synthetic and real-world datasets.

6.1. Experiment Setup

All the experiments are implemented on a machine of 256 GB RAM running Ubuntu (20.04.1) with Python 3.9.

- Datasets: We use both synthetic and real-world datasets.

- Zipf datasets. We generate several datasets of size 1,000,000 following Zipf distribution, with skewness parameters ranging from to (bigger denotes higher skewness) and the data domain fixed at 500 for simplicity. The Zipf distribution reflects the skewed frequency patterns commonly found in real-world workloads.

- Gaussian dataset. We also generate a dataset of size 1,000,000 following Gaussian distribution, with a mean of 5,000 and a standard deviation of 50.

- Twitter ego-network dataset (https://snap.stanford.edu/data/ego-Twitter.html, accessed on 26 September 2025). Real-world dataset consists of data from 2,420,766 items across 77,072 domains from the Twitter app.

- Facebook ego-network dataset (https://snap.stanford.edu/data/ego-Facebook.html, accessed on 26 September 2025). Real-world dataset consists of data from 352,936 items across 4039 domains from the Facebook app.

- Competitors: To illustrate the effectiveness of our algorithm, we compare our SDPJoinSketch (SJS) and SDPJoinSketch+ (SJS+) with existing representative SDP, LDP, and DP methods.

SDP methods: Hist_KR [20], SFLH [33].

- Hist_KR. Applying basic randomized response mechanism on the ESA framework.

- SFLH. A Fast variant of SLH [33], which combines privacy amplification theory based on optimally local hashing.

LDP methods: KRR [11], FLH [12], LDPJoinSketch [15].

- KRR. K-ary randomized response that perturbs the join values and computes the join size with calibrated frequency vectors.

- FLH. The heuristic fast variant of Optimal Local Hashing (OLH), where multiple counters are used to improve efficiency.

- LDPJoinSketch (LJS). A sketch-based join size estimation method under LDP.

CDP methods: Laplace Mechanism [39].

- Laplace Mechanism (Lap). Ensuring privacy by adding noise drawn from a Laplace distribution to the original data.

Note that except LJS, all compared methods calculate the join size by the inner product of estimated frequency vectors. Intuitively, the SDP methods strike better balance between privacy and utility, which means they have better accuracy than LDP methods and more relaxed privacy assumption than CDP methods.

- Metrics: In the experiments, we use Absolute Error (AE) and Relative Error (RE) to measure data utility performance.

- Absolute Error (AE). , is the actual join size, is the estimated result, and T is the testing rounds.

- Relative Error (RE). . The parameters are the same as those defined in AE.

- Methodology: We set by default. The result for each experiment is averaged over 10 runs with different hash seeds. The threshold is set to 0.1 for Zipf datasets, 0.01 for the Gaussian dataset, and 0.001 for Twitter and Facebook datasets. The privacy budget involved in the experiments represents the central guarantee.

6.2. Utility Comparison

We compare the performance of our algorithm SJS and SJS+ with several state-of-the-art methods. Particularly, we analyze the impact of different parameters on the accuracy of join size estimation on both synthetic and real-world datasets.

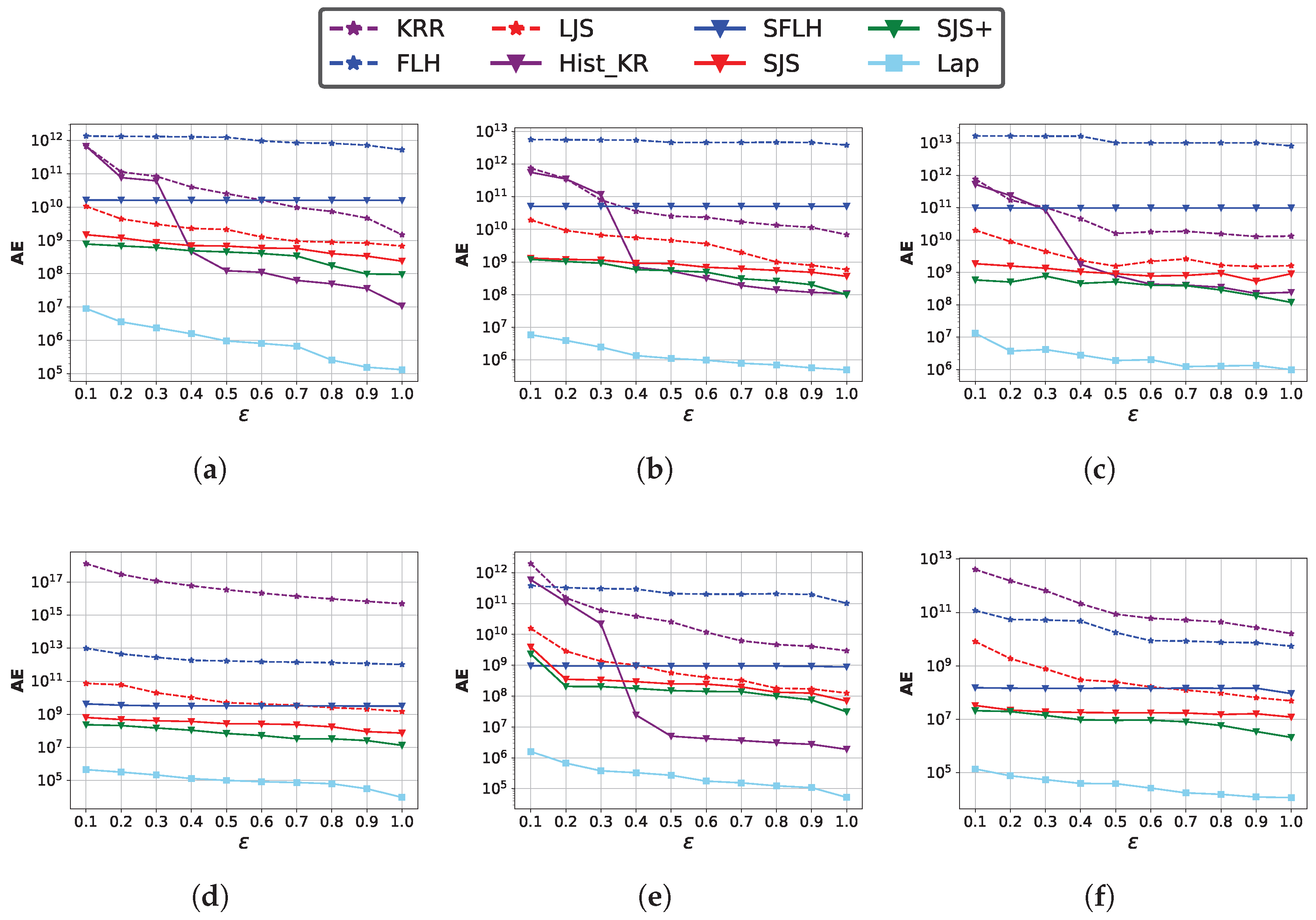

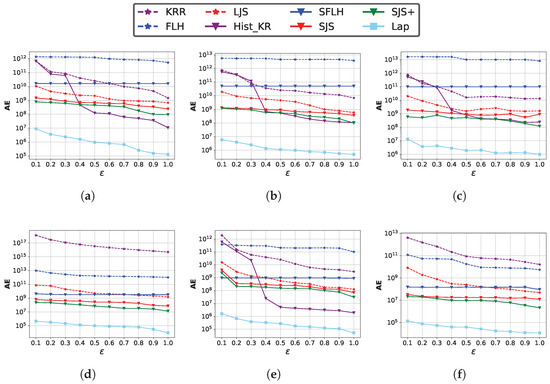

Impact of privacy budget . We vary the overall privacy guarantee against the server from 0.1 to 1 and plot AE. The sketch parameters are set to and the sample rate is fixed at . Figure 7 shows the results on both synthetic and real-world datasets. We observe that the accuracy of all methods improves as the value of increases, and when is small, our proposed methods SJS and SJS+ have better utility than SFLH and other methods under LDP. We ignore the result of Hist_KR on the Twitter dataset and Zipf datasets with due to its unsatisfactory results with the privacy amplification effect when d is too large [20]. Hist_KR performs the best when is large, but it incurs a significant communication overhead (shown in subsequent experimental results), making its implementation impractical. The experimental results for each method are the averages of 10 independent runs, with the errors relative to the mean being minimal (typically within a few percentage points), indicating that the final results exhibit high robustness.

Figure 7.

Impact of the privacy budget on the estimation accuracy of join size. (a) Zipf (); (b) Zipf (); (c) Zipf (); (d) Twitter; (e) Gaussian; (f) Facebook.

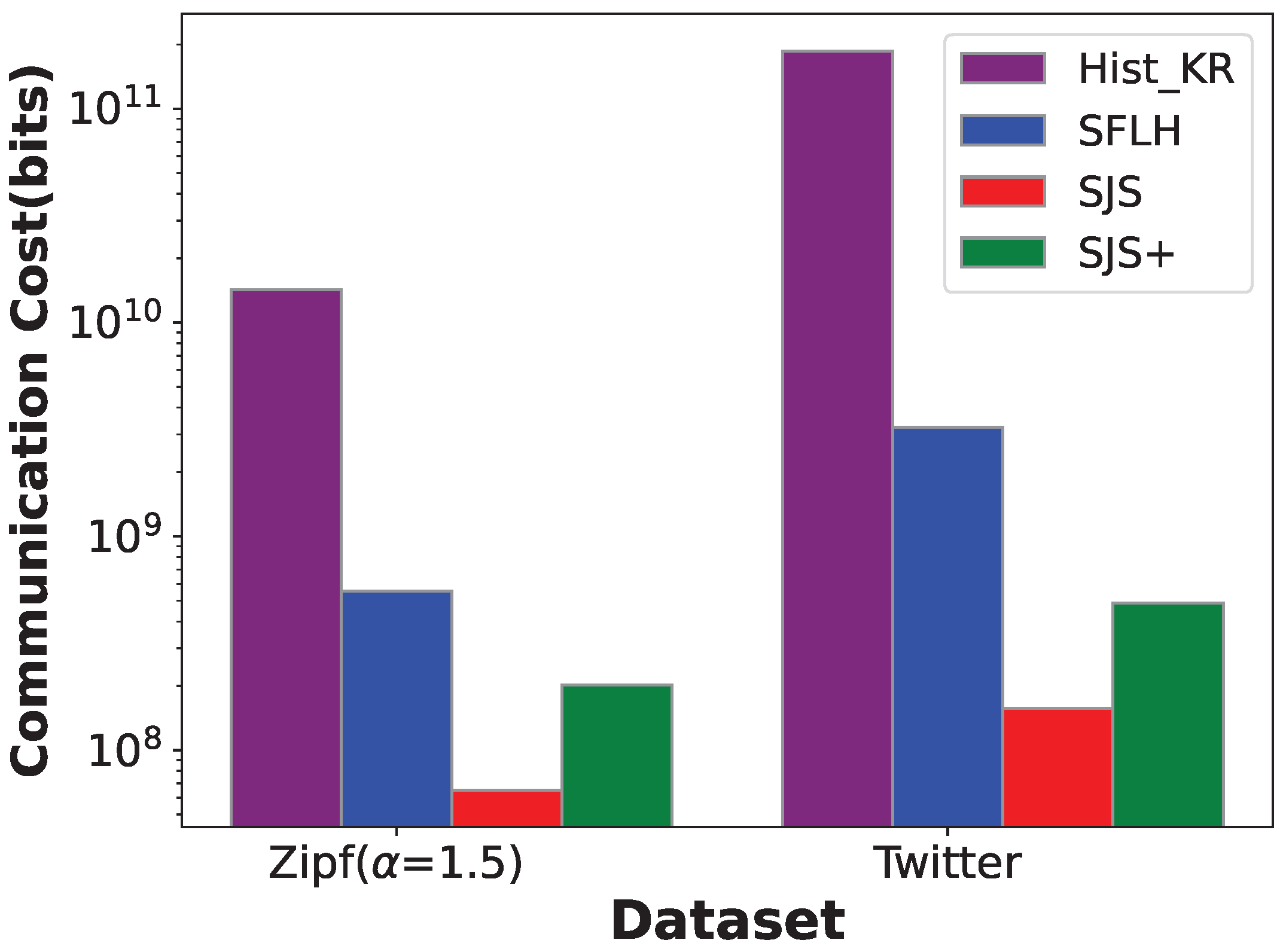

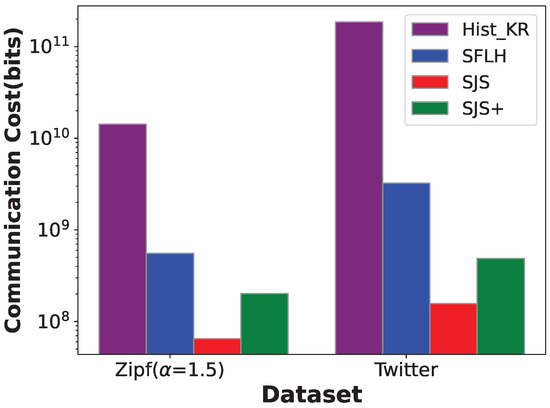

Communication cost. Figure 8 shows the communication costs of different SDP methods on Zipf () and Twitter datasets. The sketch parameters for SJS and SJS+ are set to , and the central privacy budget . We can observe that Hist_KR has the highest communication cost, especially on the Twitter dataset, whose data domain is extremely large. Both Hist_KR and SFLH have communication overhead that exhibits a logarithmic relationship with the size of data domain, i.e., , making it difficult for practical applications. Instead, the communication overhead of our SJS and SJS+ is independent of the domain and can be further reduced by optimizing the encryption technique in SJS+.

Figure 8.

Communication cost on Zipf () and Twitter datasets.

Impact of sampling rate r. We fix , , and evaluate the performance of SJS+ by varying r from 0.1 to 0.5 on Zipf datasets. Figure 9 shows the results. Consistent with our analysis in Section 5.2, the estimation error of SJS+ increases with the increase in sampling rate.

Figure 9.

Impact of sampling rate r on the estimation error of SJS+.

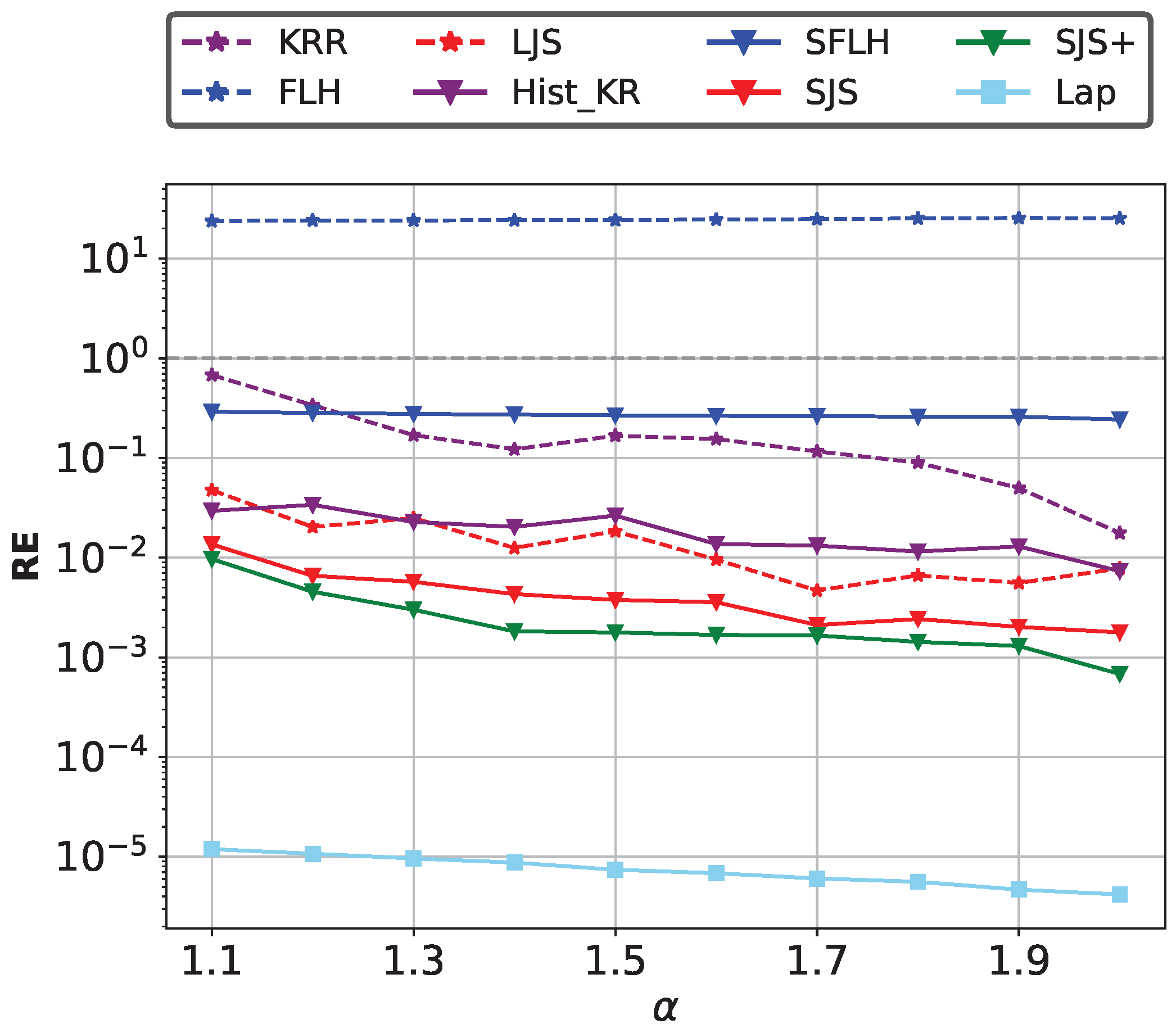

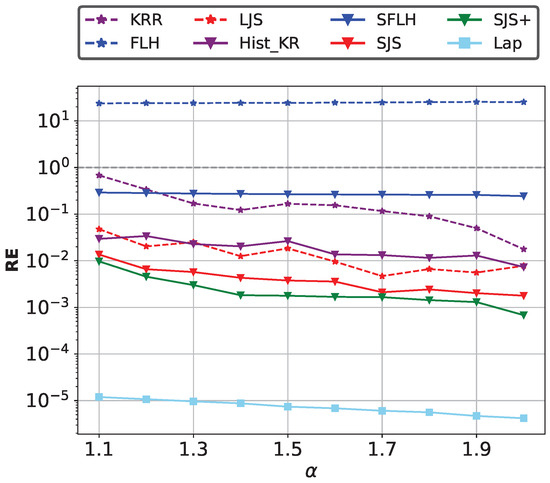

Impact of the data skewness. We fix , , . We evaluate the performance of different methods on Zipf datasets with the skewness parameter varying from to , where larger indicates higher skewness. When the RE is below the grey dotted line, it indicates that the method is effective. As shown in Figure 10, SJS and SJS+ achieve better utility with different skewness levels because of the separation of high-frequency and low-frequency items for reducing hash collisions.

Figure 10.

Impact of data skewness on join size estimation accuracy.

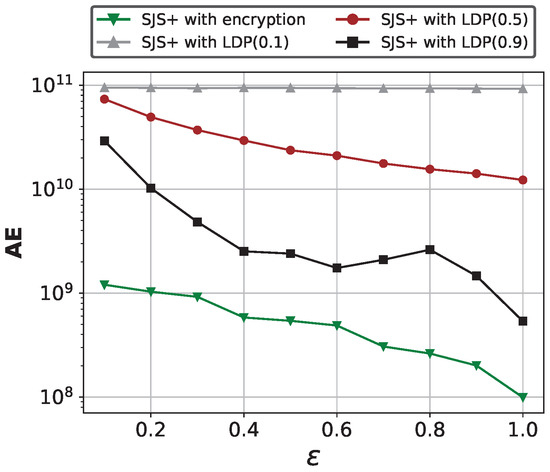

Comparison between encryption and LDP perturbation for frequency property in SDPJoinSketch+. To verify the effectiveness and necessity of using secure encryption methods on frequency properties in SJS+, we compare it with traditional differential privacy methods that add noise to the properties. Note that the information uploaded by users in the second phase can be regarded as a two-dimensional value, i.e., the value to be inserted to the sketch and the frequency property t. Therefore, the privacy budget needs to be divided to satisfy local differential privacy. Figure 11 shows the results of AE comparison between using encryption and directly adding LDP noise to the frequency properties on Zipf (), where we fix , . The decimal values in parentheses indicate the portion of the privacy budget allocated to the frequency properties. We can find that the encryption technique outperforms the LDP methods. And the more randomness added to the frequencies, the lower the estimation accuracy, which further demonstrates the necessity of preserving the true information of frequency properties.

Figure 11.

Encryption vs. LDP perturbation for frequency property in SDPJoinSketch+.

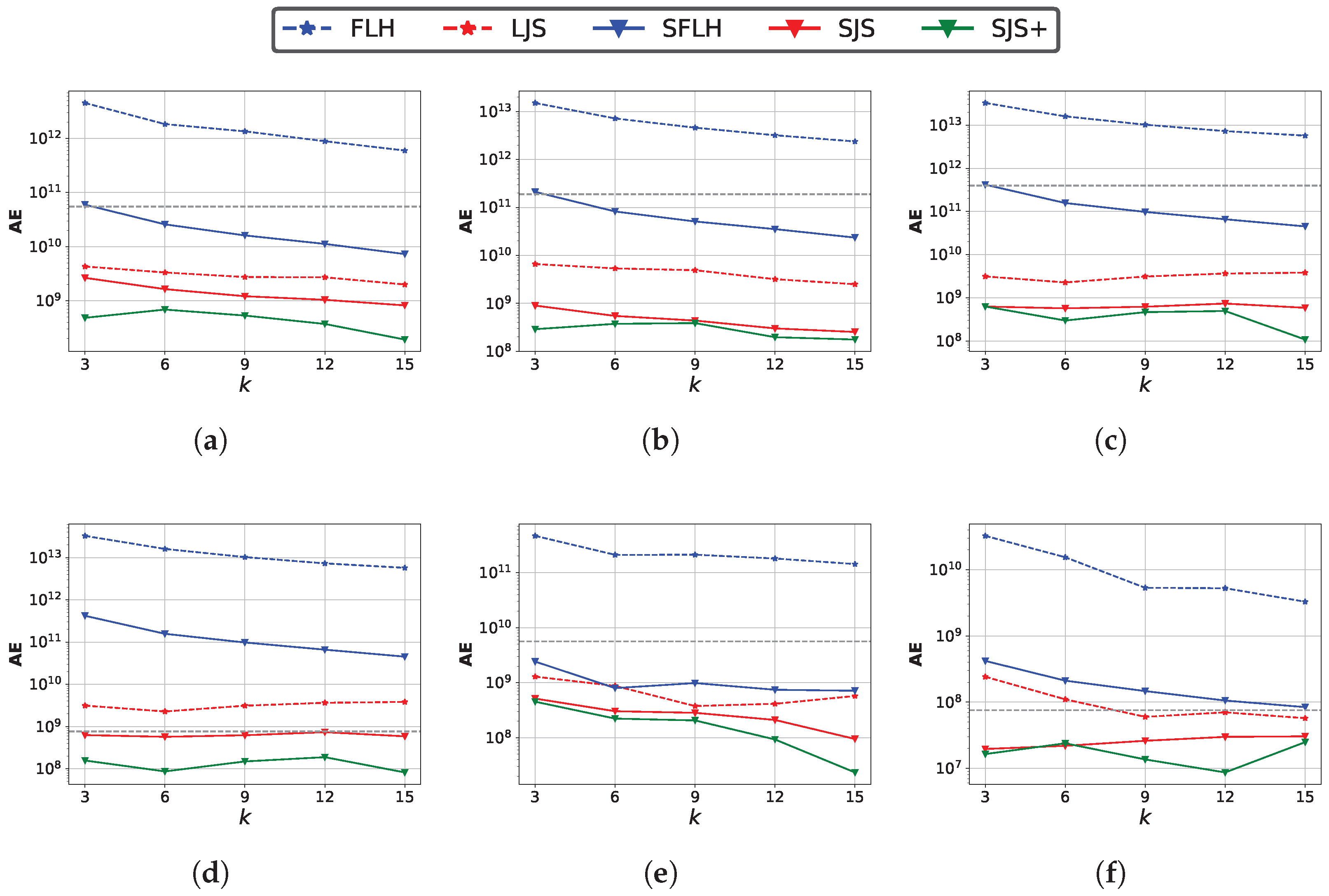

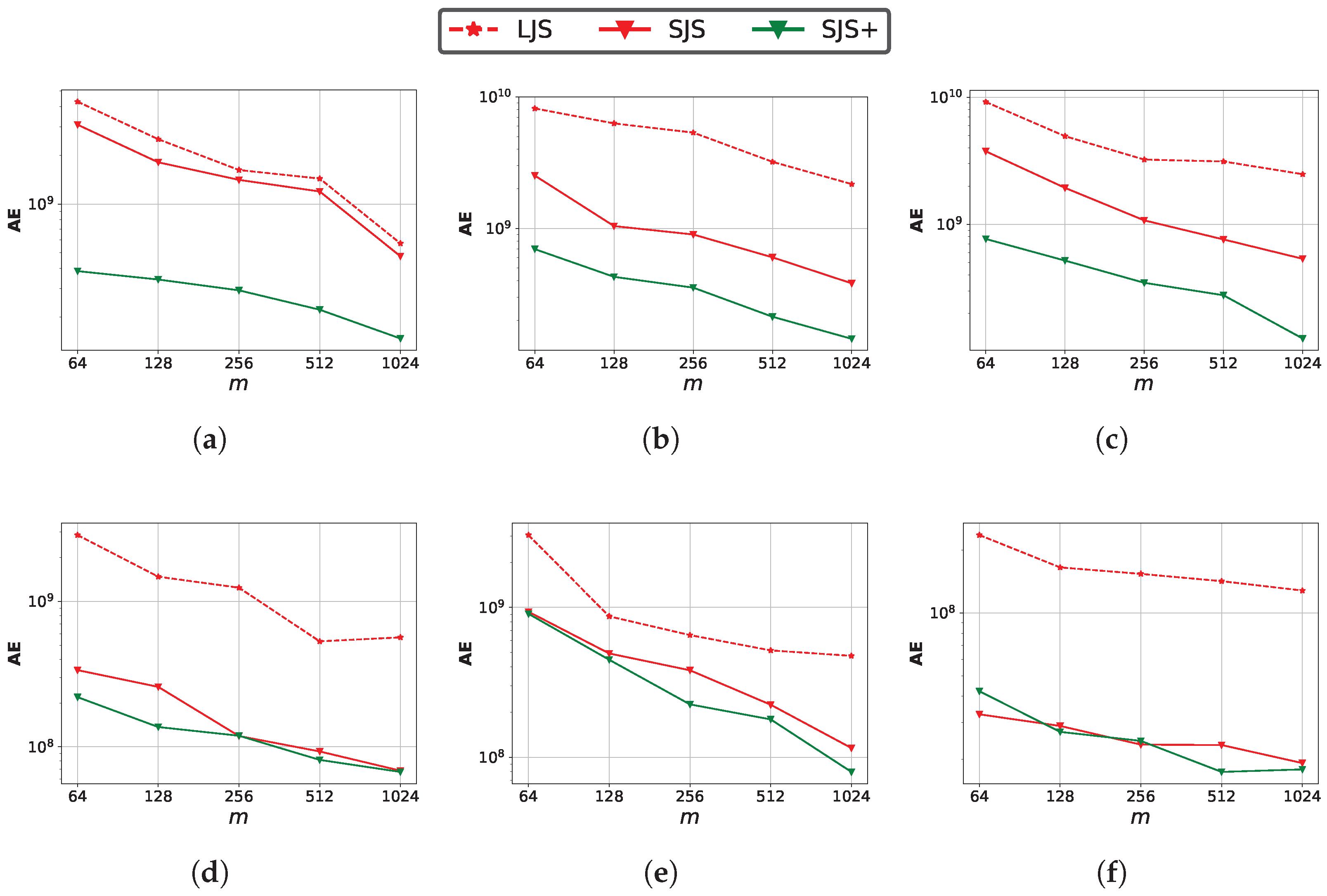

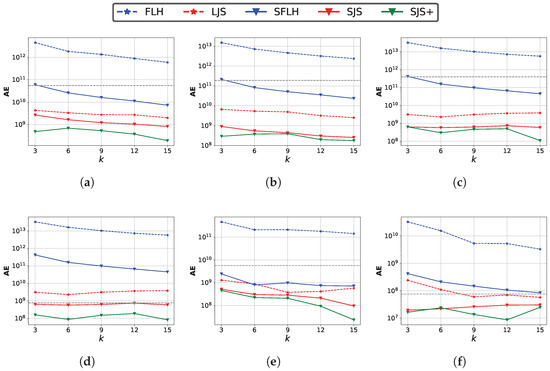

Impact of sketch size . We set and evaluate the impact of different sketch sizes. We first fix and vary k in a range of . When the AE is below the grey dotted line, it indicates that the method is effective. Figure 12 shows the impact of k on estimation accuracy. SJS and SJS+ also perform the best. The absolute error decreases as k increases, because more estimation results are used to calculate the median, which helps reduce the error. However, when k becomes too large, it may lead to the accumulation of systematic bias or an increase in the proportion of extreme values, thereby reducing the estimation accuracy. Second, we fix and vary m in a range of .

Figure 12.

Impact of sketch size parameter k on the join size estimation accuracy. (a) k:Zipf ( = 1.1); (b) k:Zipf ( = 1.5); (c) k:Zipf ( = 2.0); (d) k:Twitter; (e) k:Gaussian; (f) k:Facebook.

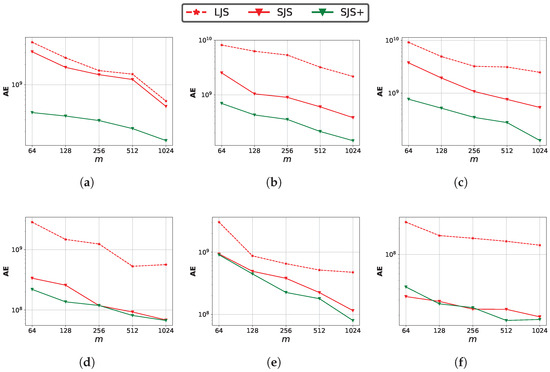

Figure 13 shows the impact of m. The error of all methods decreases as m increases due to the lower hash-collision probability, but it may cause higher space and computation cost.

Figure 13.

Impact of sketch size parameter m on the join size estimation accuracy. (a) m:Zipf ( = 1.1); (b) m:Zipf ( = 1.5); (c) m:Zipf ( = 2.0); (d) m:Twitter; (e) m:Gaussian; (f) m:Facebook.

Summaries of experimental results.

- SDPJoinSketch has better utility than methods under LDP for join size estimation.

- The enhanced mechanism SDPJoinSketch+ further improves utility by reducing hash-collision errors and has smaller communication overhead than conventional LDP protocols.

- Dealing with high-skewed data with small privacy budget, our proposed methods demonstrate better performance.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we study the problem of join size estimation under the shuffle model of differential privacy. We propose a sketch-based method SDPJoinSketch and analyze its privacy amplification via shuffling. Furthermore, to reduce errors caused by hash-collision between high- and low-frequency items, we propose an improved method SDPJoinSketch+, which is a two-stage framework leveraging the advantages of the shuffle model to separate high-frequency and low-frequency items with secure encryption techniques during sketch construction, thus improving the utility of join size estimation. Experimental results show that our methods outperform state-of-the-art ones with respect to utility.

Future work: First, we consider techniques to improve the efficiency and handling more complex join operations such as self-joins and joins with predicates under SDP. Second, we consider further improving utility by optimizing the process of sketch construction, such as choosing an appropriate construction method to reduce unnecessary errors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and X.L.; methodology, M.Z.; software, X.L. and Y.M.; validation, M.Z. and X.L.; formal analysis, M.Z.; investigation, M.Z.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, X.L. and Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and X.L.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., X.L., M.L. and Y.M.; visualization, X.L. and Y.M.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, administration; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSFC grant 62202113; Joint Funding Special Project for Guangdong—Hong Kong Science and Technology Innovation 2024A0505040027; China Southern Power Grid Research Institute Project (No. 1500002024030103XA00091).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leis, V.; Radke, B.; Gubichev, A.; Mirchev, A.; Boncz, P.; Kemper, A.; Neumann, T. Query optimization through the looking glass, and what we found running the join order benchmark. VLDB J. 2018, 27, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Balazinska, M.; Suciu, D. From theory to practice: Efficient join query evaluation in a parallel database system. In Proceedings of the 2015 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 31 May–4 June 2015; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, Q.; Wang, C.; Lui, J.C.; Guan, X. A memory-efficient sketch method for estimating high similarities in streaming sets. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bessa, A.; Daliri, M.; Freire, J.; Musco, C.; Musco, C.; Santos, A.; Zhang, H. Weighted minwise hashing beats linear sketching for inner product estimation. In Proceedings of the 42nd ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGAI Symposium on Principles of Database Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–23 June 2023; pp. 169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C. Differential privacy. In Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming, Venice, Italy, 10–14 July 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Duchi, J.C.; Jordan, M.I.; Wainwright, M.J. Local privacy and statistical minimax rates. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 54th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Berkeley, CA, USA, 26–29 October 2013; pp. 429–438. [Google Scholar]

- Differential Privacy Team, Apple. Learning with Privacy at Scale Differential. 2017. Available online: https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/learning-with-privacy-at-scale (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Erlingsson, Ú.; Pihur, V.; Korolova, A. Rappor: Randomized aggregatable privacy-preserving ordinal response. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3–7 November 2014; pp. 1054–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Fanti, G.C.; Pihur, V.; Erlingsson, Ú. Building a RAPPOR with the Unknown: Privacy-Preserving Learning of Associations and Data Dictionaries. Proc. Priv. Enhancing Technol. 2016, 2016, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Kulkarni, J.; Yekhanin, S. Collecting telemetry data privately. In Proceedings of the NIPS’17: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Blocki, J.; Li, N.; Jha, S. Locally differentially private protocols for frequency estimation. In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 17), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–18 August 2017; pp. 729–745. [Google Scholar]

- Cormode, G.; Maddock, S.; Maple, C. Frequency estimation under local differential privacy [experiments, analysis and benchmarks]. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.16640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, N.; Jha, S. Locally differentially private heavy hitter identification. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2019, 18, 982–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yu, T.; Khalil, I.; Xiao, X.; Ren, K. Heavy hitter estimation over set-valued data with local differential privacy. In Proceedings of the CCS’16: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Yin, L. Sketches-Based Join Size Estimation Under Local Differential Privacy. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Utrecht, The Netherlands, 13–16 May 2024; pp. 1726–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, Ú.; Feldman, V.; Mironov, I.; Raghunathan, A.; Talwar, K.; Thakurta, A. Amplification by shuffling: From local to central differential privacy via anonymity. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, SIAM, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–9 January 2019; pp. 2468–2479. [Google Scholar]

- Cheu, A.; Smith, A.; Ullman, J.; Zeber, D.; Zhilyaev, M. Distributed differential privacy via shuffling. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Darmstadt, Germany, 19–23 May 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 375–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazi, B.; Golowich, N.; Kumar, R.; Manurangsi, P.; Pagh, R.; Velingker, A. Pure differentially private summation from anonymous messages. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.01919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, B.; Golowich, N.; Kumar, R.; Pagh, R.; Velingker, A. On the power of multiple anonymous messages: Frequency estimation and selection in the shuffle model of differential privacy. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Madrid, Spain, 4–8 May 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 463–488. [Google Scholar]

- Balle, B.; Bell, J.; Gascón, A.; Nissim, K. The privacy blanket of the shuffle model. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 18–22 August 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 638–667. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, S.; Yin, L. Local differentially private frequency estimation based on learned sketches. Inf. Sci. 2023, 649, 119667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, F.; Dobra, A. Sketches for size of join estimation. ACM Trans. Database Syst. (TODS) 2008, 33, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, N.; Matias, Y.; Szegedy, M. The space complexity of approximating the frequency moments. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 22–24 May 1996; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Alon, N.; Gibbons, P.B.; Matias, Y.; Szegedy, M. Tracking join and self-join sizes in limited storage. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 31 May–2 June 1999; pp. 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cormode, G.; Garofalakis, M. Sketching streams through the net: Distributed approximate query tracking. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, Trondheim, Norway, 30 August–2 September 2005; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, S.; Kesh, D.; Saha, C. Practical algorithms for tracking database join sizes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Foundations of Software Technology and Theoretical Computer Science, Hyderabad, India, 15–18 December 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly, S.; Garofalakis, M.; Rastogi, R. Processing data-stream join aggregates using skimmed sketches. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Extending Database Technology, Crete, Greece, 14–18 March 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 569–586. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Tu, Y.; Yu, L.; Cui, B. JoinSketch: A Sketch Algorithm for Accurate and Unbiased Inner-Product Estimation. In Proceedings of the ACM on Management of Data, Seattle, WA, USA, 18 June–23 June 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ion, M.; Kreuter, B.; Nergiz, A.E.; Patel, S.; Saxena, S.; Seth, K.; Raykova, M.; Shanahan, D.; Yung, M. On deploying secure computing: Private intersection-sum-with-cardinality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P), Genoa, Italy, 7–11 September 2020; pp. 370–389. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lee, X.; Peng, B.; Palpanas, T.; Xue, J. Privsketch: A private sketch-based frequency estimation protocol for data streams. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications, Penang, Malaysia, 28–30 August 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. DPSW-Sketch: A Differentially Private Sketch Framework for Frequency Estimation over Sliding Windows. In Proceedings of the KDD ’24: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 3255–3266. [Google Scholar]

- Bittau, A.; Erlingsson, Ú.; Maniatis, P.; Mironov, I.; Raghunathan, A.; Lie, D.; Rudominer, M.; Kode, U.; Tinnes, J.; Seefeld, B. Prochlo: Strong privacy for analytics in the crowd. In Proceedings of the 26th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Shanghai, China, 28–31 October 2017; pp. 441–459. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Ding, B.; Xu, M.; Huang, Z.; Hong, C.; Zhou, J.; Li, N.; Jha, S. Improving utility and security of the shuffler-based differential privacy. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.11515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, B.; Kumar, R.; Manurangsi, P.; Pagh, R.; Sinha, A. Differentially private aggregation in the shuffle model: Almost central accuracy in almost a single message. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 3692–3701. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Gu, Y.; Tang, P.; Yu, G. Collecting and analyzing key-value data under shuffled differential privacy. Front. Comput. Sci. 2023, 17, 172606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balle, B.; Bell, J.; Gascón, A.; Nissim, K. Private summation in the multi-message shuffle model. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 657–676. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yi, K. Frequency Estimation in the Shuffle Model with Almost a Single Message. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7–11 November 2022; pp. 2219–2232. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming; Pearson Education: London, UK, 1997; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; McSherry, F.; Nissim, K.; Smith, A. Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis. In Proceedings of the Theory of Cryptography: Third Theory of Cryptography Conference, TCC 2006, New York, NY, USA, 4–7 March 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 265–284. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).