1. Introduction

According to Chen et al. [

1], Taiwan’s wafer foundry output accounts for approximately 70% of the global total, while its packaging and testing output accounts for about 50%, ranking first worldwide in both categories. In addition, some studies also point out that Taiwan’s machine tool output value ranks among the top in the world and plays an important role [

2]. Notably, central Taiwan has developed a substantial machine tool industry cluster, integrating intelligent precision machinery, machine tools, and the aerospace industry with component processing and maintenance sectors [

3,

4]. Within Taiwan’s machine tool industry, a segment is dedicated to manufacturing machine tools for the semiconductor industry [

5]. Given the stringent quality requirements of semiconductor processes, the quality standards for these tools are exceptionally high. Since semiconductor manufacturing machine tools are assembled from hundreds of components, the quality of each component must meet required standards to ensure that the final machine tools satisfy overall quality requirements. Likewise, each component has multiple quality characteristics, all of which must comply with quality standards to guarantee that the component attains the desired quality level [

6,

7].

In practice, each component must undergo several processing steps before completion. Once completed, certain quality characteristics may meet the required quality standards, while others may fall short and require improvement. It is also necessary to determine the direction of such improvements. Clearly, without a comprehensive evaluation model, it is difficult for field engineers to ensure the final quality of component products. To address this issue—which is the objective of this study—we adopt the most widely used industry metric, the Process Capability Index [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], to construct a quality evaluation and analysis model suitable for products with multiple quality characteristics. This method enables process engineers to simultaneously assess all product quality attributes and determine whether they meet the expected quality standards. For products that do not meet these standards, the model provides improvement directions and supports decision-making based on cost and economic efficiency, thereby ensuring the final product quality.

Several studies have noted that both the critical components of machine tools and the products manufactured using machine tools typically encompass numerous quality characteristics [

13,

14,

15,

16]. In addition, the process capability index is commonly employed in the machine tool sector as a decision-making tool for evaluating and analyzing process quality [

17].

, originally proposed by Kane [

17], continues to be the most widely utilized measure for assessing process capability in industry. The random variable

X denotes the process distribution corresponding to a given quality characteristic. Assuming normality,

X is distributed normally with mean

and variance

, denoted as

. Moreover, the process capability index,

, is expressed as follows:

where

USL means the upper specification limit, while

LSL denotes the lower specification limit. Both the upper and lower specification limits are set according to customer requirements. Furthermore,

d (

USL LSL)/2 corresponds half the length of the specification interval, and the target

T (

USL LSL)/2 represents the midpoint of the specification interval. As noted by Chen et al. [

18], the relationship between

and process yield is given by

As the process capability index

increases, the corresponding process yield (

) also increases. For example, when

equals 1.0 (

1.0), the corresponding process yield is at least 99.73% (

99.73%). Clearly,

effectively reflects both process capability and process yield. Consequently, this index is used to construct a chart for evaluating and analyzing process capability in multi-quality-characteristic products. Moreover,

, which denotes a function of the precision index

and the accuracy index

, is redefined as follows:

where

and

. In fact,

and

are unknown parameters. According to Montgomery [

19], process capability evaluation must be conducted under statistical process control to determine stable process capability. Furthermore, according to Chen et al. [

1], provided that

and

are properly controlled,

can be maintained. Accordingly, this study estimates

and

utilizing control chart data under statistical process control with normal distribution, while simultaneously deriving their joint confidence region. In accordance with statistical testing principles, evaluation coordinates are established for all quality characteristics of the product. Subsequently, plotting these coordinates on the process capability evaluation and analysis chart facilitates the development of assessment criteria for all quality characteristics. This also allows process engineers to simultaneously monitor whether all quality characteristics of the product meet required quality standards through the process capability evaluation and analysis chart. For those quality characteristics that fail to meet the required levels, the approach further facilitates analysis of process precision or accuracy, providing guidance for process engineers to implement improvements.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, a chart is developed as a tool for evaluating and analyzing process capability in multi-quality-characteristic component products.

Section 3 establishes evaluation coordinates for quality characteristics based on statistical testing principles and defines corresponding evaluation rules.

Section 4 presents a case study illustrating the implementation of the proposed model. Lastly,

Section 5 presents the conclusion of the study.

2. Multi-Quality-Characteristic Process Capability Evaluation and Analysis Chart

According to Equation (3), the process capability index

serves as a function of the precision index

and the accuracy index

, where

and

When the accuracy index equals zero (

), it indicates that the process mean

precisely coincides with the target value

T. When the accuracy index is greater than zero (

), it indicates a rightward shift of the process mean. For instance,

signifies that the process mean

is shifted one-third of a tolerance unit to the right of the target value

T. As the accuracy index increases, the process exhibits a greater rightward shift. Conversely,

represents a leftward shift of the process; for instance,

signifies that the process mean

is shifted one-fourth of a tolerance unit to the left of the target value

T. The more negative the accuracy index, the greater the leftward shift of the process. According to Chen et al. [

20], when

and

, the process achieves a

-sigma quality level. Similarly, when

and

, the process attains a 6-sigma quality level. Based on the above, the correspondence between the process capability index

and the

-sigma quality level can be expressed as follows:

According to Equation (6), the correspondence between

and the

-sigma quality level can be shown in

Table 1.

When process engineers specify the required quality level as

k-sigma,

Table 1 indicates that the corresponding required value of the process capability index

is

v, where

. Then,

As noted earlier, each component comprises multiple quality characteristics, and each characteristic must satisfy the desired quality level to ensure that the component product as a whole attains the specified quality standard. According to Yu et al. [

21], the required process capability index for each individual quality characteristic must exceed that of the overall product. In other words, the process capability index of the entire product can be guaranteed to exceed the required value

v only if the process capability indices of all individual quality characteristics are greater than the specified value

.

Suppose a component product possesses

q quality characteristics. Let the random variable

be defined as following a normal distribution of the

hth quality characteristic, with process mean

and process variance

, denoted as

. Based on Equation (2) and the aforementioned concept, this study defines the process capability index for the entire component product as follows:

where

, representing the process capability index of the

hth quality characteristic, is defined as follows:

Evidently, when the process capability indices of all

q quality characteristics exceed the specified value

(

,

h = 1, 2, …,

q), the process capability index of the entire component product equals

v. Then,

The correspondence between the required value

v of

for the entire component product and the specified value

of

for individual quality characteristics is presented in

Table 2.

Remark: The value should be based on Equation (10).

As mentioned above, when process engineers set the process capability index of the entire component product to

v,

Table 2 presents the corresponding required value,

, of the process capability indices for individual quality characteristics. Thus, we have

for

and

for

. Clearly, when the required value of the process capability index

is

, the process capability acceptance zone

may be established as follows:

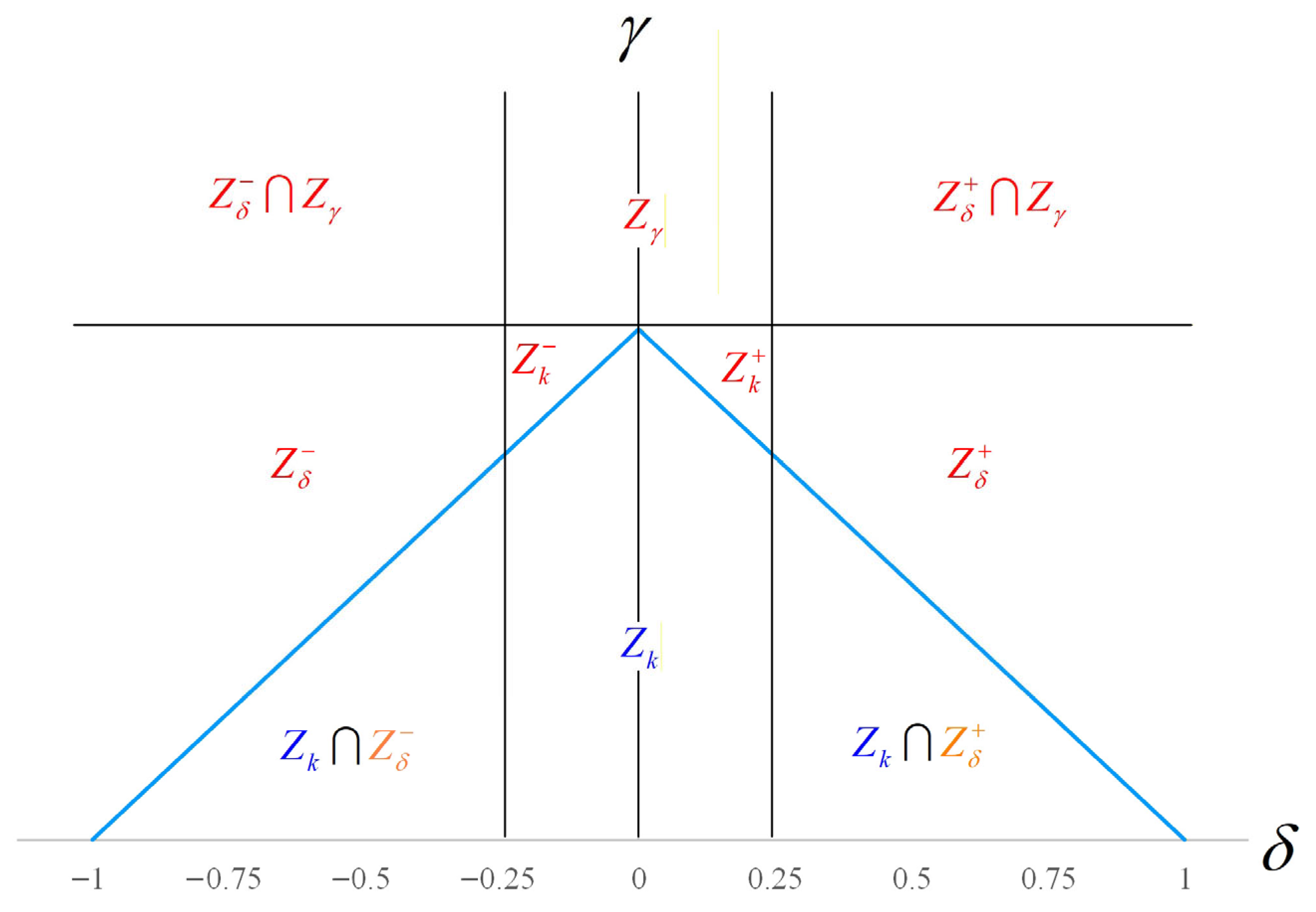

Obviously, when the coordinates of the accuracy index and the precision index for quality characteristic h fall within the process capability acceptance zone , that is , the process capability of quality characteristic h is considered to satisfy the desired k-sigma quality level (). Conversely, when the coordinates of the accuracy index and the precision index for quality characteristic h do not fall within the process capability acceptance zone , that is , the process capability of quality characteristic h is considered to fail to meet the required quality level ().

Next, based on the aforementioned concepts, this study constructs a multi-quality- characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart. For example, a component product has four critical quality characteristics. When process engineers require the product to achieve a 6-sigma process quality level, this corresponds to a process capability index of 1.50 (

v = 1.50) for the entire component product and a process capability index of 1.60 (

= 1.60) for each individual quality characteristic. In the following, the horizontal axis (

x-axis) corresponds to

, and the vertical axis (

y-axis) corresponds to

. The resulting multi-quality-characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart is shown as follows (

Figure 1):

3. Constructing Measurement Coordinates

Since the accuracy index

and the precision index

for quality characteristic

h are two unknown parameters, sample data are required for their estimation. In general, engineers typically conduct process capability evaluation of product quality characteristics only under statistical process control, that is, when the process is stable [

19,

22]. In most industries, quality control engineers monitor manufacturing process quality using the mean–standard deviation (

) control chart. The process associated with the

hth quality characteristic is assumed to follow a normal distribution, denoted as

. Several studies have suggested that the number of subgroups

m is usually 20 or 25. These

m subgroups and their associated observations can be expressed as follows:

Given the process target

and tolerance

, this study defines the random variable as follows:

Clearly, the random variable

is defined to follow a normal distribution with mean

and variance

, denoted as

. Accordingly, the control chart data described above can be redefined as follows:

Under statistical process control, the estimators for the process accuracy index

and the process precision index

of the

hth quality characteristic are expressed as follows:

and

where

and

Many studies have indicated that point estimates are susceptible to misjudgment due to sampling error [

23]. Therefore, using the control chart data presented previously, this study derives the 100(1 −

)% joint confidence region for the accuracy index

and the precision index

of the

hth quality characteristic. Given normality, the random variable

is defined as follows:

Then, the random variable

follows a

t-distribution characterized by

N −

n degrees of freedom, denoted as

. Similarly, the random variable

is defined as follows:

Then, the random variable

follows a chi-square distribution characterized by

N − n degrees of freedom, denoted as

. Therefore,

The 100(

)% confidence interval for the accuracy index

of the

hth quality characteristic is [

,

], expressed as follows:

where

denotes the upper

quintile of the

t-distribution characterized by

N −

n degrees of freedom. Similarly,

Therefore, the 100(

)% confidence interval for the precision index

of the

hth quality characteristic is [

,

], represented as follows:

where

is the lower

quintile of the chi-square distribution characterized by

N − n degrees of freedom and

is the lower

quintile of the chi-square distribution characterized by

N − n degrees of freedom. To determine the 100(

)% confidence region of

, this study introduces the events

and

as follows:

Obviously,

and

. Applying Boole’s inequality and DeMorgan’s rules [

24], we obtain

. Thus,

Therefore, the 100(

)% confidence region of

can be defined as follows:

Clearly, the 100 (1−

)% confidence region of

is a rectangle, with its four vertices given by:

As previously mentioned, when process engineers require a product to attain a

k-sigma level of process quality, the corresponding required index for the product is

. Based on the total number of quality characteristics in the product,

Table 2 can be employed to determine the required value

for the

hth quality characteristic. Accordingly, the null and alternative hypotheses for the statistical test are expressed as follows:

null hypothesis

alternative hypothesis

Given a significance level of for the statistical test, the following cases are considered:

If , the intersection of zone and confidence region CR is not an empty set , then it can be deduced that value process capability index of quality characteristic h is greater than

If , the intersection of zone and confidence region CR is an empty set , then it can be deduced that value process capability index of quality characteristic h is smaller than

If , the intersection of zone and confidence region CR is not an empty set , then it can be deduced that value process capability index of quality characteristic h is greater than

If , the intersection of zone and confidence region CR is an empty set , then it can be deduced that value process capability index of quality characteristic h is smaller than

Considering the two cases described above, the measurement coordinate

of quality characteristic

h can be defined as:

Next, considering the position of the coordinate for the hth quality characteristic, the process quality of this characteristic is evaluated using the following measurement rules:

- (1)

Given , the process capability index exceeds , indicating that the quality level of the hth quality characteristic has reached the k-sigma standard.

- (2)

Given , the process capability index is below , indicating that the quality level of the hth quality characteristic has not achieved the 6-sigma standard. Accordingly, the process quality of this characteristic requires improvement.

Based on the above, process engineers can determine whether process improvement is necessary by assessing whether the evaluation coordinate

of each quality characteristic falls within the process quality acceptance zone. In addition to the process quality acceptance zone

, this study defines process quality improvement recommendation zones according to the levels of process precision and accuracy, as outlined below:

According to several studies, when a process shift occurs—indicated by the accuracy index being significantly greater or less than zero—it often suggests that performance can be improved through adjustments to machine parameters alone. In such cases, the associated improvement cost () tends to be relatively low. This scenario typically corresponds to conditions represented by or . Conversely, when process variation is excessive, it may stem from factors such as unstable material supply, improper tool selection or control, or aging equipment. These issues generally result in a higher improvement cost (), and are characteristic of conditions represented by . When process improvement is required, it is advisable to consider both categories of improvement costs in order to enhance either the accuracy or the precision of the process.

Next, the process quality acceptance zone, along with all process quality improvement recommendation zones described above, is plotted on the multi-quality-characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart, as shown below (

Figure 2):

Based on whether the evaluation coordinate of each quality characteristic falls within the multi-quality-characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart described above, this study establishes the following rules for evaluation and improvement recommendations:

When it indicates that the process quality of quality characteristic h achieves the desired quality level, and no improvement is necessary.

When , it reveals that the process quality of quality characteristic h fails to attain the required quality level. If the process engineer can consider improving process accuracy through measures such as adjusting machine parameters, the improvement cost () of process deviation will usually not be too high. Therefore, improvements can be made to improve the overall process quality standard.

When , it shows that the process quality of quality characteristic h fails to satisfy the required quality standard. If the process engineer can consider improving process accuracy through measures such as adjusting machine parameters, the improvement cost () of process deviation will usually not be too high. Therefore, improvements can be made to improve the overall process quality standard.

When , it reveals that the process quality of quality characteristic h meets the desired quality level, and no improvement is necessary. However, since the process accuracy index of this quality characteristic exceeds 1/4 (), if process engineers can consider improving process accuracy by adjusting machine parameters, the cost of improvement () will not be too high, and improvements can be made, thereby improving the overall process quality standards.

When , it reveals that the process quality of quality characteristic h meets the desired quality level, and no improvement is necessary. However, since the process accuracy index of this characteristic is less than

), if process engineers can consider improving process accuracy by adjusting machine parameters, the cost of improvement () will not be too high, and improvements can be made, thereby improving the overall process quality standards.

Given , it indicates that the process quality of quality characteristic h fails to meet the desired quality standard and therefore requires improvement. Since the process accuracy index of this quality characteristic exceeds 1/4 (), even if the cost of improving is very high, process engineers must make improvements and improve process accuracy to improve the overall process quality and meet the quality level requirements.

Given , it reveals that the process quality of quality characteristic h fails to achieve the specified quality level and therefore requires improvement. Since the process accuracy index of this quality characteristic is less than −1/4 (), even if the cost of improving is very high, process engineers must make improvements and improve process accuracy to improve the overall process quality and meet the quality level requirements. process engineers may consider enhancing process accuracy through machine parameter adjustments, thereby further improving the overall process quality.

Given , it indicates that the process quality of quality characteristic h has not yet reached the required quality level and requires improvement. Although the cost of improvement () for process variation is high, process engineers should still use various methods to reduce process variability, thereby improving process precision and overall process quality.

Given , it indicates that the process quality of quality characteristic h has not yet reached the required quality level and requires improvement. Process variation typically has a lower cost of improvement () and can be improved first. However, since the cost of improvement () for process variation is high, process engineers should still employ various methods to reduce process variation to improve process precision and overall process quality.

Given , it indicates that the process quality of quality characteristic h has not yet reached the required quality level and requires improvement. Process variation typically has a lower cost of improvement () and can be improved first. However, since the cost of improvement () for process variation is high, process engineers should still employ various methods to reduce process variation to improve process precision and overall process quality.

4. Practical Application

Taiwan plays a critical role in the global supply chain of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, primarily used for chip manufacturing at the 7 nm, 5 nm, and even more advanced process nodes. In advanced wafer fabrication, optical inspection is essential for ensuring quality control. With the adoption of Deep Ultraviolet (DUV) technology, inspection resolution has improved, enabling higher sensitivity to submicron defects such as crystal displacements and microcracks. Consequently, Automated Optical Inspection (AOI) has become a vital component of advanced processes. By integrating multi-model sensing with machine vision algorithms, AOI continues to provide optimal solutions for high-quality advanced manufacturing. As noted in the introduction, all important components in AOI equipment must meet stringent quality standards, with each quality characteristic subject to strict tolerances and demanding process quality requirements. This study adopts the filter holder of an automated optical inspection system as a case study illustrating the application of the methods presented in the previous two sections. The filter holder comprises nine key quality characteristics, and their corresponding tolerances are listed in the following table (

Table 3).

According to Equation (10) and

Table 2, when the required product process quality attains a 6-sigma quality level, the corresponding minimum value for the product’s process capability index

is 1.50 (

v = 1.50). Given that the filter holder has nine key quality characteristics, this corresponds to a required process capability index of 1.65 (

= 1.65) for each individual quality characteristic. To assess whether the process capability index

of the

hth quality characteristic is greater than or equal to 1.65, the null and alternative hypotheses for the statistical test are defined as follows:

and

As mentioned above, this study plots the accuracy index on the horizontal axis (x-axis) and the precision index on the vertical axis (y-axis).

Next, this study constructs the evaluation coordinates of the nine key quality characteristics using the control chart data for the average standard deviation () under statistical process control. Accordingly, the confidence intervals for all quality characteristics are calculated as follows:

According to Equation (19),

,

, and

, together with the confidence intervals for each quality characteristic, are calculated as follows (

Table 4):

According to

Table 4 and Equation (30), the evaluation coordinates for those nine quality characteristics are computed as shown in the table below (

Table 5):

Based on the aforementioned equations, the process quality zones have been calculated as follows:

The evaluation coordinates of the nine quality characteristics presented in the above table are plotted on the multi-quality characteristic process capability evaluation and improvement chart for the filter holder, as presented in

Figure 3.

Next, based on the evaluation and improvement guidelines established in this study, the nine quality characteristics are analyzed as follows:

Quality Characteristic 1: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic fails to meet the desired level and therefore requires improvement. Since its process accuracy index value is greater than 1/4 (), process engineers may consider adjusting machine parameters to reduce the process mean, thereby enhancing process accuracy and improving the overall process quality level.

Quality Characteristic 2: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic fails to achieve the required standard and therefore requires improvement. Process engineers may enhance process accuracy by adjusting machine parameters to correct right-skewness, thereby lifting the overall process quality level.

Quality Characteristic 3: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic fails to meet the desired standard and therefore requires improvement. Since its process accuracy index is greater than 1/4 (), process engineers may consider adjusting machine parameters to lower the process mean, thereby enhancing process accuracy, and in turn, the overall process quality level.

Quality Characteristic 4: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic fails to achieve the desired standard and thus requires improvement. Process engineers may enhance process precision by reducing process variability, thereby elevating the overall process quality level.

Quality Characteristic 5: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic meets the desired standard and therefore requires no improvement. However, since its process accuracy index is greater than 1/4 (), process engineers may consider adjusting machine parameters to lower the process mean—provided the cost is not prohibitive—in order to further enhance process accuracy and elevate the overall process quality.

Quality Characteristic 6: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic meets the desired standard and therefore requires no improvement. However, since its process accuracy index is greater than 1/4 (), process engineers may consider adjusting machine parameters to lower the process mean, provided that the cost is not prohibitive, in order to further enhance process accuracy and thereby improve the overall process quality level.

Quality Characteristic 7: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic satisfies the required quality standard and does not require improvement—only maintenance is necessary.

Quality Characteristic 8: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic satisfies the required quality standard and does not require improvement—only maintenance is necessary.

Quality Characteristic 9: . This represents that the process quality of this characteristic attains the desired level and does not require improvement—only maintenance is necessary.

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

Since a machine tool used in semiconductor manufacturing is assembled from hundreds of components, the quality of each component must meet the required standards to ensure that the machine tool as a whole achieves the desired quality level. Likewise, each component has multiple quality characteristics, all of which must conform to the required standards to guarantee the component’s quality. Accordingly, this study employed the process capability index,

, widely applied in the machine tool industry, to develop a multi-quality-characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart, which serves as a tool for evaluating and analyzing component products. Notably, the process capability index

of quality characteristic

h depends on both the precision index

and the accuracy index

. Given that these two indices are unknown parameters, Chen et al. [

1] demonstrated that the process capability index

can be ensured as long as the precision and accuracy indices for each quality characteristic are properly controlled. Consequently, this study utilized control chart data within the framework of statistical process control to estimate the precision index

and accuracy index

of each quality characteristic

h, and further derived their joint confidence region. Based on the principles of statistical hypothesis testing, evaluation coordinates were constructed for all quality characteristics. By plotting these coordinates

on the process capability evaluation and analysis chart, evaluation criteria for all quality characteristics were established. The advantages of the evaluation model proposed in this paper are: (1) the evaluation model established based on statistical test meth can control producer risks; (2) it enables process engineers to use charts to simultaneously monitor all quality characteristics of the product and evaluate whether it meets the required quality level; (3) it proposes improvement directions for products that do not meet the expected quality standards; (4) it makes improvement decisions based on cost and economic benefits, thereby ensuring the quality of the final product. In fact, the multi-quality characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart developed in this study can be applied to the machine tool and electronics industries. Implementing the proposed framework can improve production efficiency and process quality, thereby enhancing industrial competitiveness and promoting sustainable development. In fact, the multi-quality characteristic process capability evaluation and analysis chart developed in this study can be applied to machine tool and electronics industries. Implementation of the proposed framework can improve production efficiency and process quality, thereby enhancing industrial competitiveness and promoting sustainable development.

Furthermore, this study is limited to the assumption that the process distribution follows a normal distribution and that process capability assessment and analysis can only be performed under statistical process control. When a process is not under statistical process control, attributable and unattributable causes can be investigated, analyzed, and improved to maintain the process under statistical process control.

Since process distributions sometimes do not follow a normal distribution, future research could aim to transform sample data into a normal distribution through variable transformation, while also applying the same variable transformation to tolerances, thereby modifying the model proposed in this paper and expanding its scope of application. Future research could also develop assessment models using non-parametric approaches to address non-normal process distributions.