Supply Chain Management in Times of Supply Disruption Risk and Consumer Panic Buying: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the main reasons for and impacts of consumer panic-buying behavior under supply disruption risk?

- How can we effectively manage supply chains under supply disruption risk and consumer panic-buying behavior?

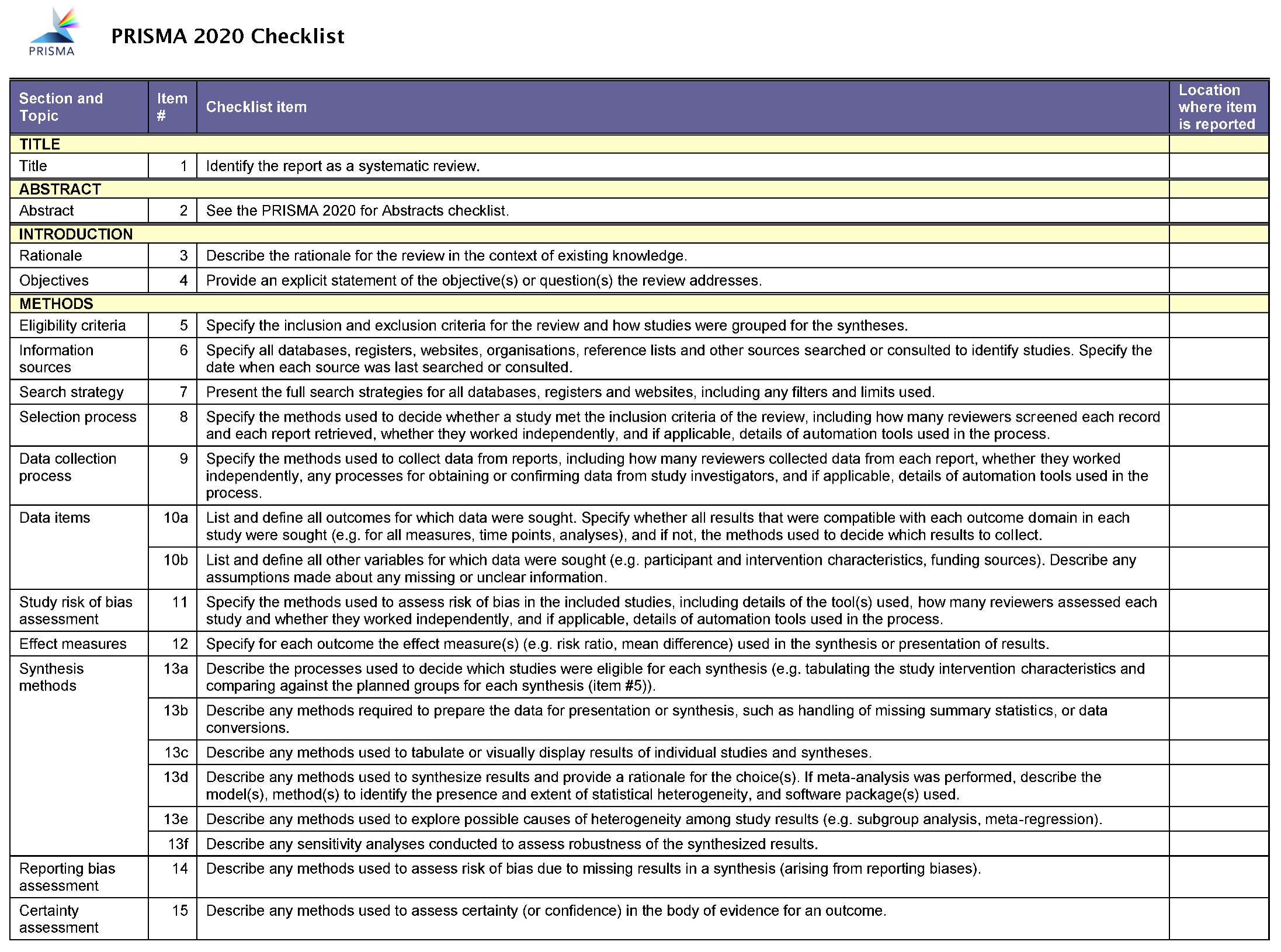

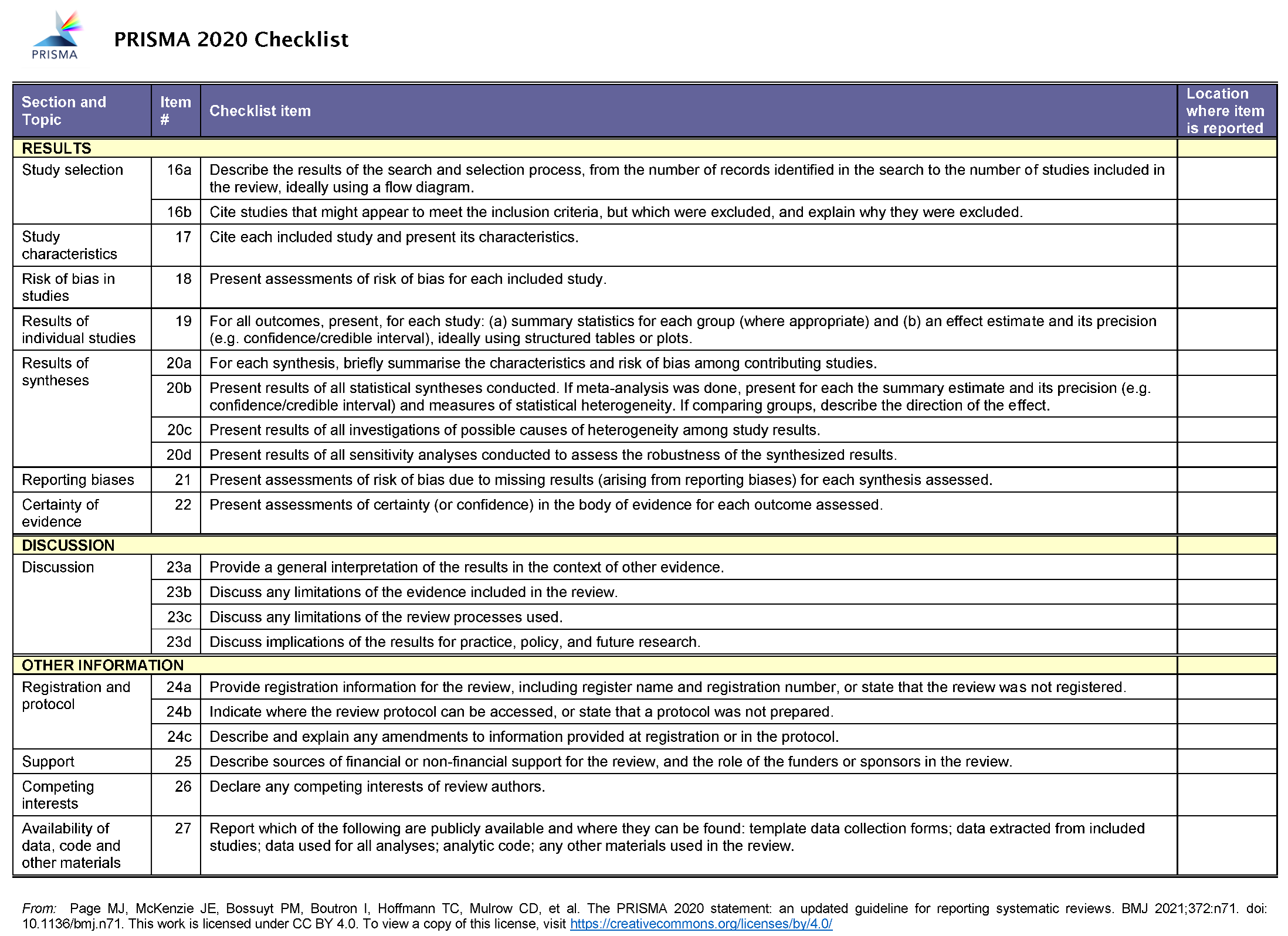

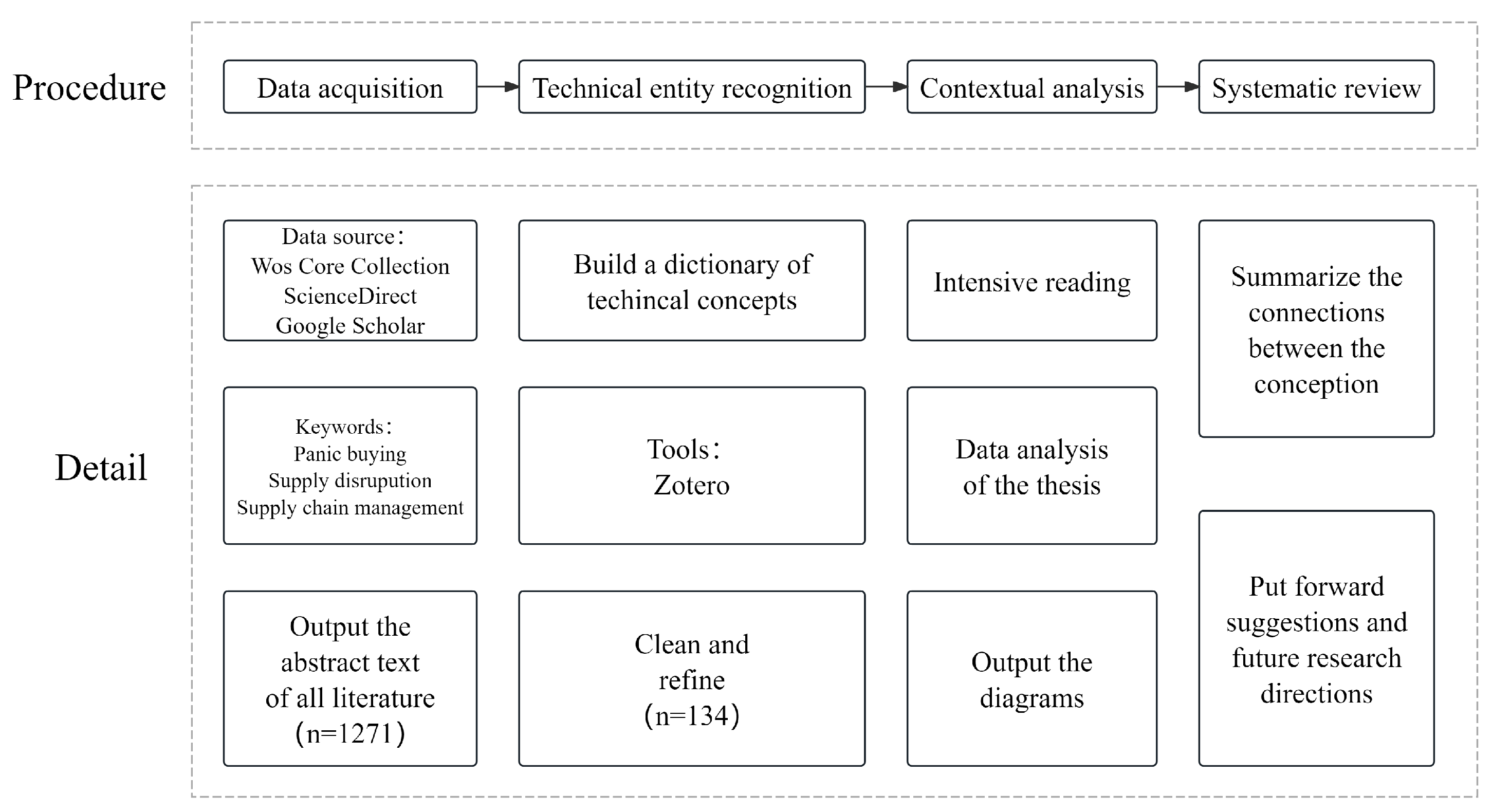

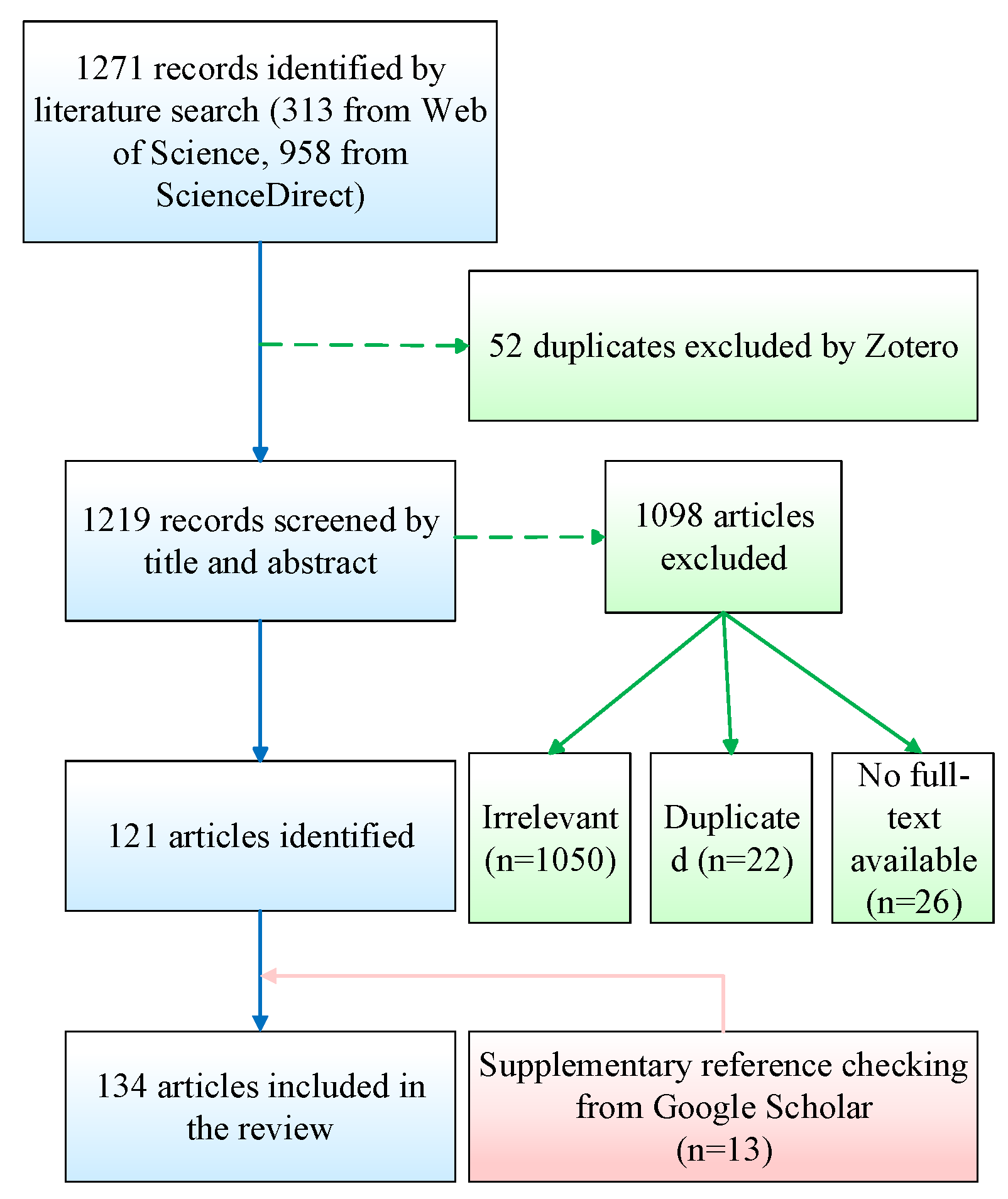

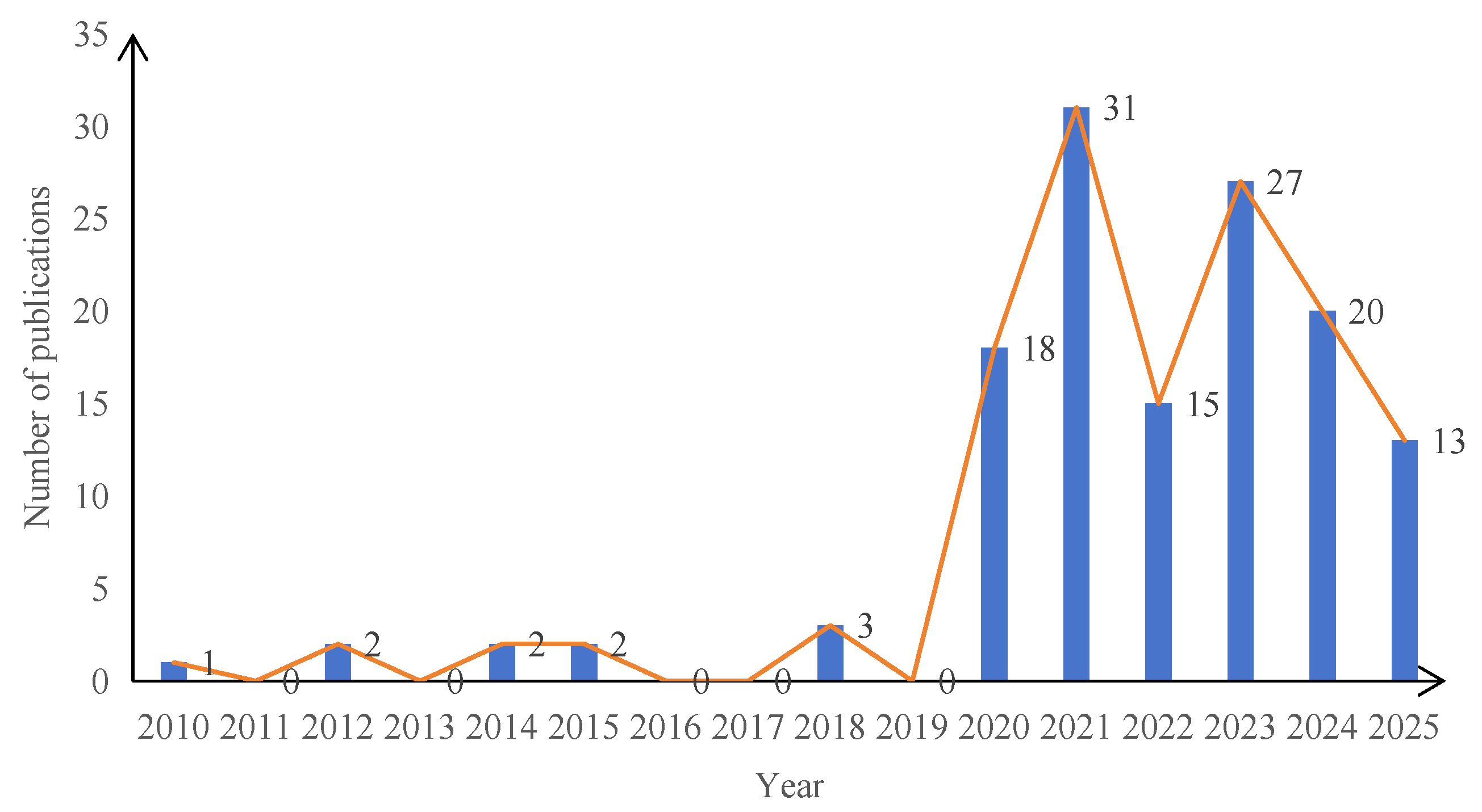

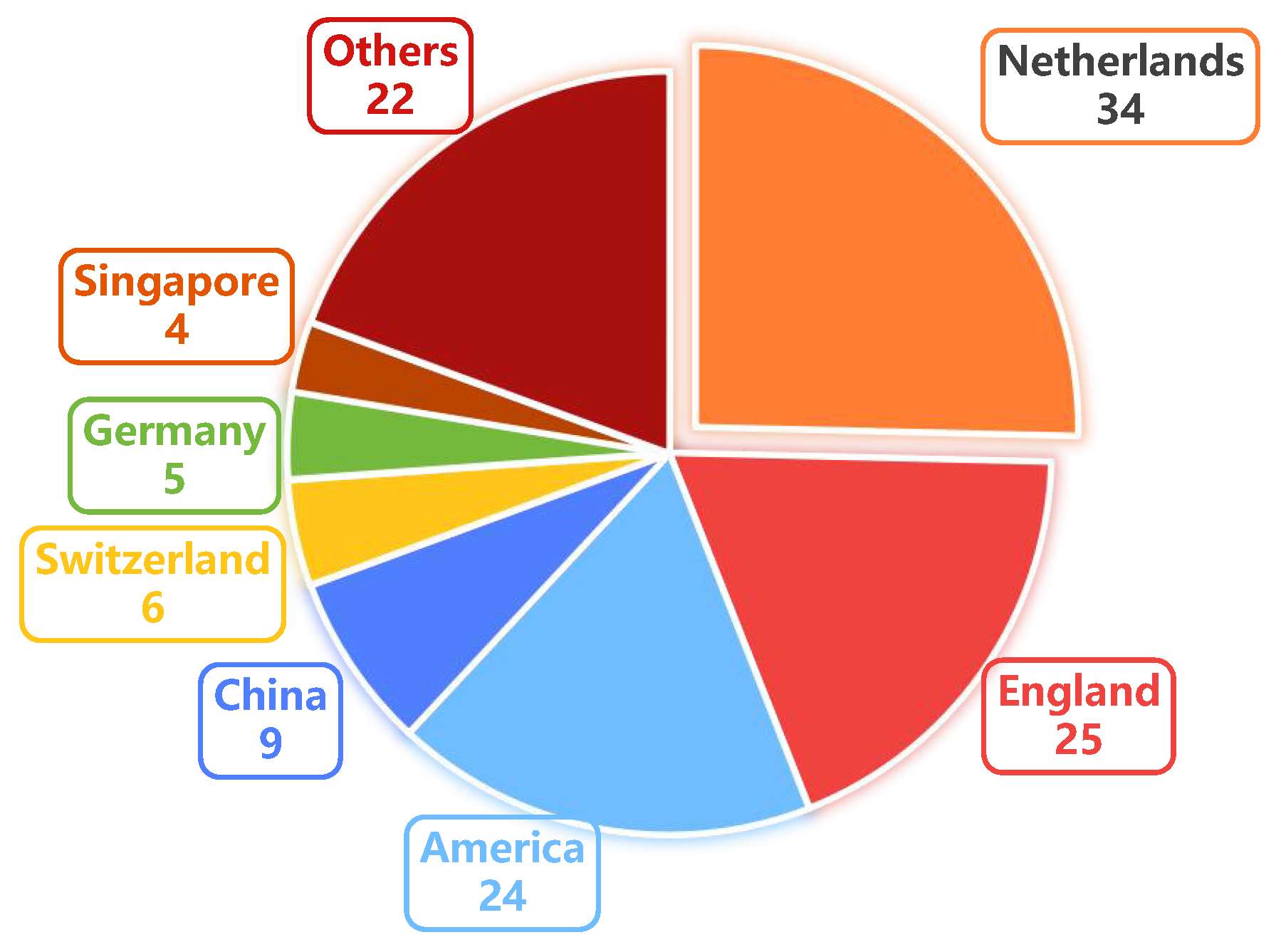

2. Methodology

- Panic buying is the irrational accumulation of goods beyond immediate needs, driven by uncertainty about future availability. This behavior is typically triggered by heightened anxiety and uncertainty, often exacerbated by external events such as pandemics, natural disasters, or geopolitical tensions [11,21].

- Supply chain management is the integrated management of the entire flow of goods, services, information, and finances, from raw material sourcing to product delivery to the end customer. Its scope spans demand planning, procurement, production, inventory management, logistics (transportation and warehousing), and distribution while emphasizing partner collaboration, sustainability, risk management, and technology-driven efficiency [15,16].

3. Consumer Panic-Buying Behavior Under Supply Disruption Risk

3.1. Consumers’ Behavioral Responses to the Risk of Supply Disruption

3.1.1. Behavioral Classification and Trigger Mechanisms

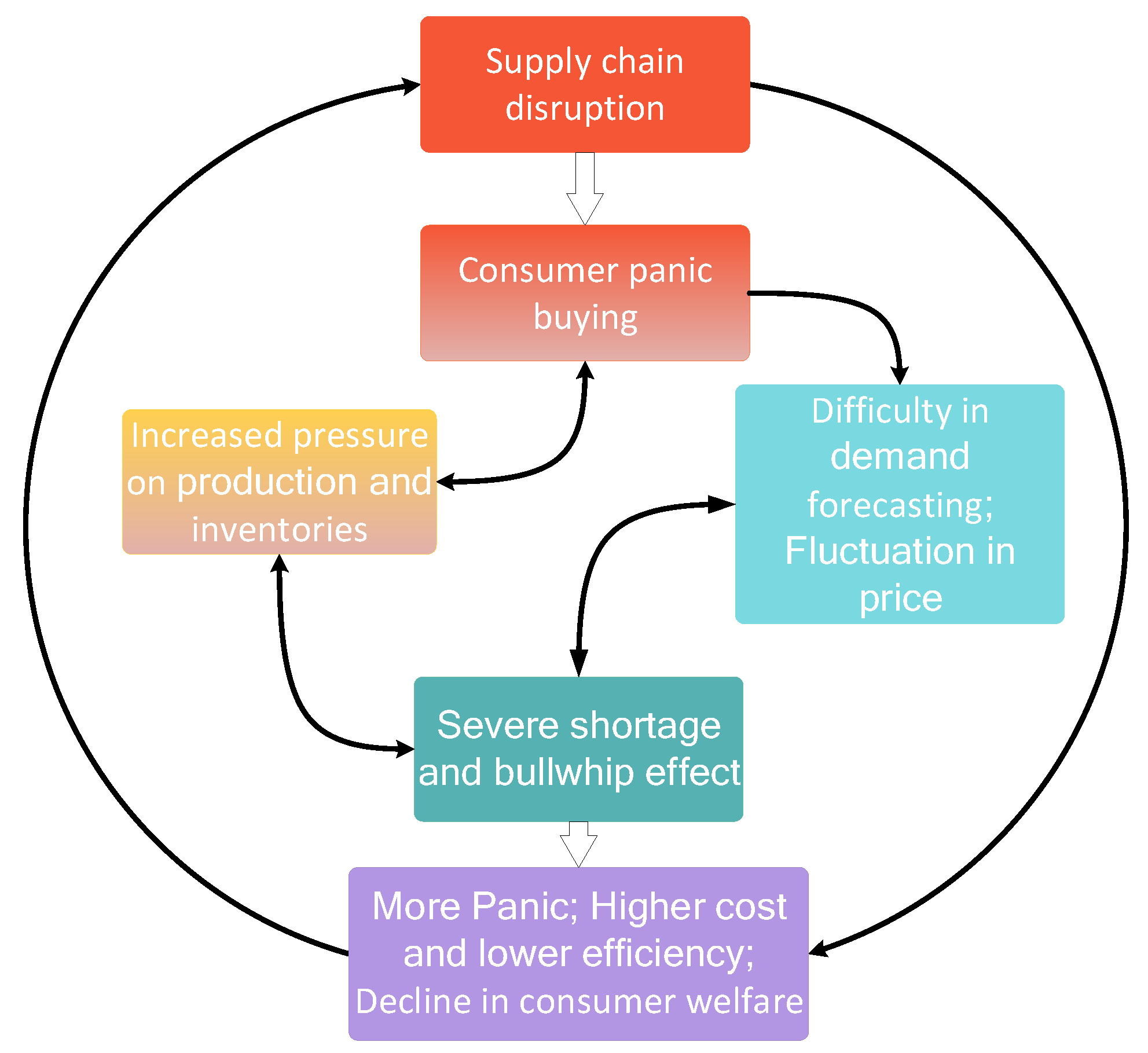

3.1.2. Chain Reactions in the Supply Chain

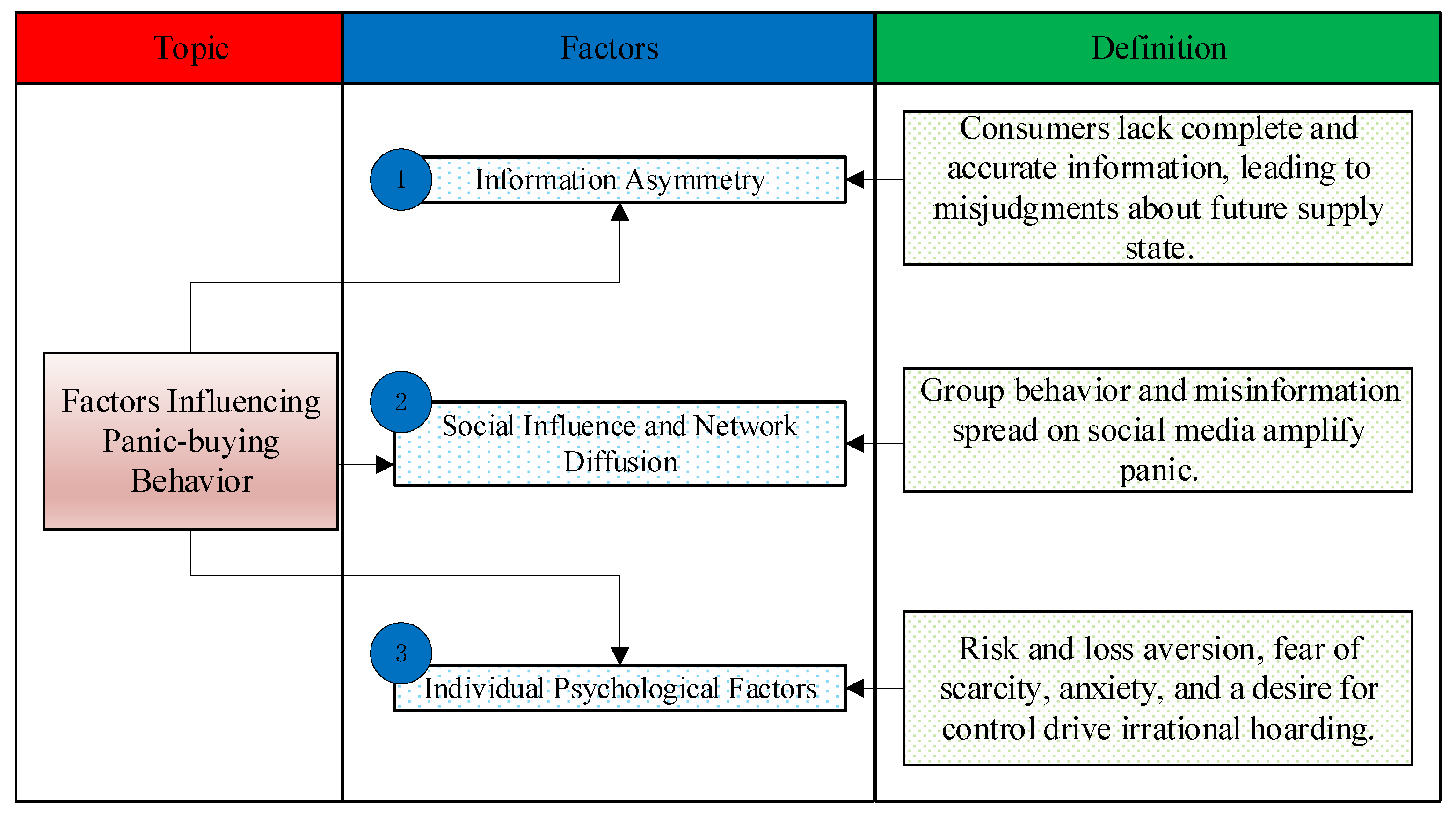

3.2. Factors Affecting Consumer Panic-Buying Behavior

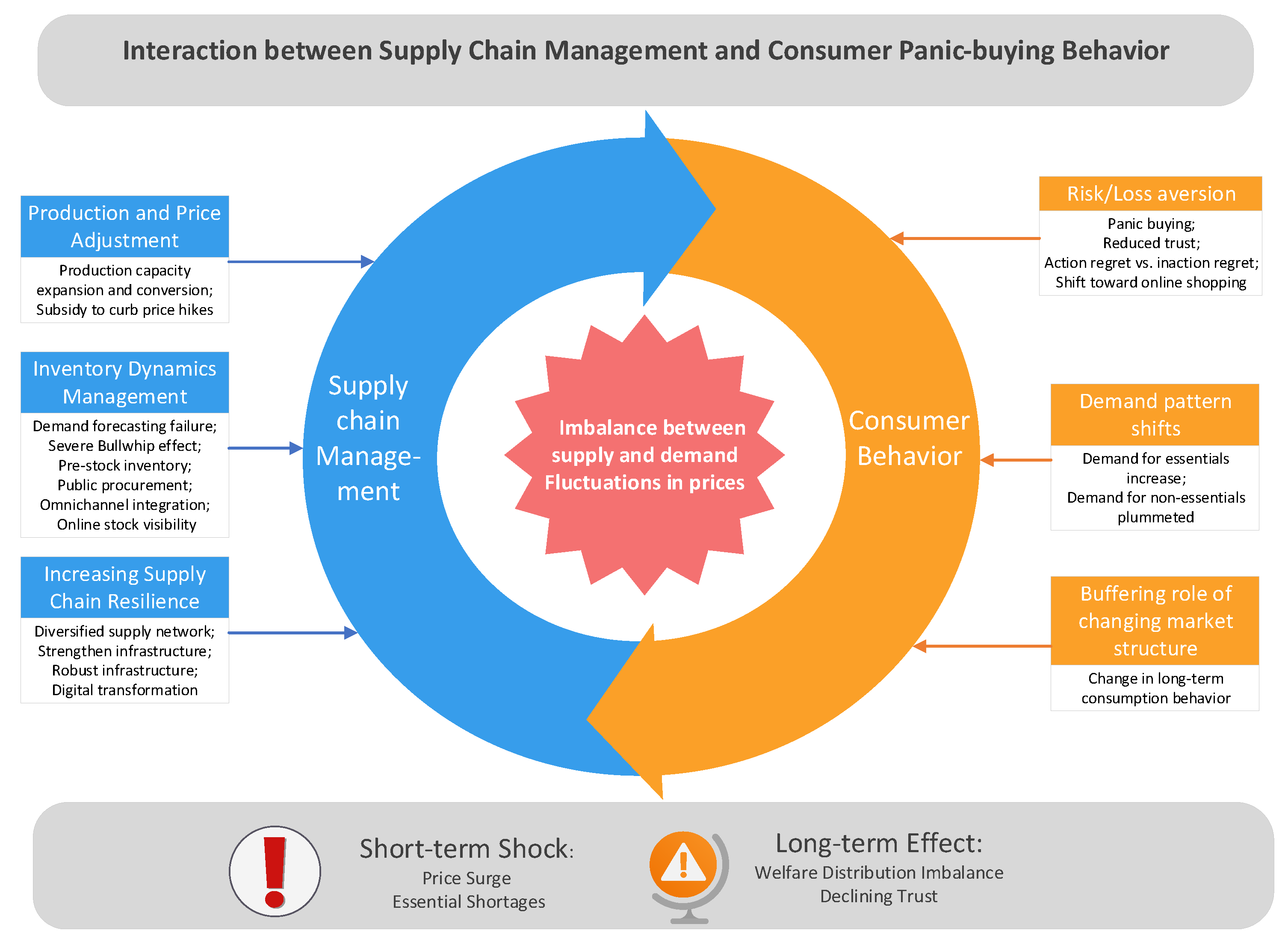

4. Supply Chain Management Under Consumer Panic-Buying Behavior

4.1. How Does Supply Chain Strategy Affect Consumer Behavior?

4.2. How Does Consumer Behavior Affect Supply Chain Management?

4.3. An Example of Interaction Between Supply Chain Management and Consumer Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.4. Supply Chain Management Strategies for Responding to Consumer Panic-Buying Behavior

4.4.1. Strategies to Alleviate Consumers’ Panic Psychology

4.4.2. Supply Chain Elasticity and Inventory Management

4.4.3. Government Intervention and Retailer Intervention

5. Impact of Panic Buying on Supply Chain Performance and Social Welfare

5.1. Impact of Panic Buying on Supply Chain Performance

5.2. Impact of Panic Buying on Consumer Welfare

5.3. Interaction Between Supply Chain Performance and Consumer Welfare

6. Discussion

6.1. A Comprehensive Analysis of Supply Chain Disruptions, Consumer Panic Buying, and Mitigation Strategies

6.2. Complex Impact of Panic Buying on Consumer Welfare and Supply Chain Performance

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

|

|

References

- Sim, K.; Chua, H.C.; Vieta, E.; Fernandez, G. The Anatomy of Panic Buying Related to the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ennews.com. Demand Surged 1400 the Shelves! 2020. Available online: https://www.ennews.com/article-14484-1.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- News, S. Fearing a Further Escalation of the Epidemic, Citizens in Hong Kong Are Hoarding, and Supermarkets Issue Purchase Restrictions. 2020. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/407848066_120051716 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Kogan, K.; Herbon, A. Retailing under Panic Buying and Consumer Stockpiling: Can Governmental Intervention Make a Difference? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 254, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenjie, S. Information Disclosure and Irrational Panic Buying Behavior: Based on COVID-19 Epidemic Analysis. Res. Manag. 2020, 41, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Arafat, S.Y.; Hakeem, S.; Kar, S.K.; Singh, R.; Shrestha, A.; Kabir, R. Communication during Disasters: Role in Contributing to and Prevention of Panic Buying. In Panic Buying and Environmental Disasters: Management and Mitigation Approaches; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panic Buying: How Grocery Stores Restock Shelves in the Age of Coronavirus | CNN Business. 2020. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/20/business/panic-buying-how-stores-restock-coronavirus/index.html (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Commerce. The Ministry of Commerce Deploys the Work of Ensuring Supply and Stabilizing Prices of Vegetable and Other Essential Goods in the Market. 2021. Available online: https://www.mofcom.gov.cn/xwfb/rcxwfb/art/2021/art_3f824a3b0aef4049af3e758832a7e46c.html (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Gurnani, H.; Mehrotra, A.; Ray, S. Supply Chain Disruptions: Theory and Practice of Managing Risk; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, Y.; Bao, L. Managing Consumers’ Panic Stockpiling Behavior under Supply Disruption Risk: Price Increase vs. Quota Policy. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2025, 39, 118–129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Billore, S.; Anisimova, T. Panic Buying Research: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yuen, K.F.; Fang, M.; Wang, X. A Literature Review on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Consumer-Centric Logistics. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2682–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazemi, R.; Farahani, S.; Otieno, W.; Jang, J. Review on Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemics: Influencing Factors, Stockpiling, and Intervention Strategies. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurek, J.; Rudy, M. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Changes in Consumer Purchasing Behavior in the Food Market with a Focus on Meat and Meat Products-A Comprehensive Literature Review. Foods 2024, 13, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durugbo, C.M.; Al-Balushi, Z. Supply Chain Management in Times of Crisis: A Systematic Review. Manag. Rev. Q. 2023, 73, 1179–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Sethi, S.P.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Lu, S.F. Designing Supply Chain Strategies against Epidemic Outbreaks Such as COVID-19: Review and Future Research Directions. Decis. Sci. 2023, 54, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2021, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Shou, B.; Yang, J. Supply Disruption Management under Consumer Panic Buying and Social Learning Effects. Omega 2021, 101, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mahfouz, A.; Arisha, A. Analysing Supply Chain Resilience: Integrating the Constructs in a Concept Mapping Framework via a Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 16–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; He, Y.; Shao, Z. Retailer’s Ordering Decisions with Consumer Panic Buying under Unexpected Events. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 266, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Pitafi, A.H.; Arya, V.; Wang, Y.; Akhtar, N.; Mubarik, S.; Xiaobei, L. Panic Buying in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multi-Country Examination. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Nair, K.; Radhakrishnan, L. Impact of COVID-19 Crisis on Stocking and Impulse Buying Behaviour of Consumers. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2021, 48, 1794–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; He, X.; Cheng, T. Retailer Hoarding in Emergency Situations: A Game-Theoretic Analysis. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2025, 200, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Shou, B.; Guo, P. Managing Panic Buying with Bayesian Persuasion. Work. Pap. 2024, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P. A Production Recovery Plan in Manufacturing Supply Chains for a High-Demand Item during COVID-19. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 51, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ying, S.; Xu, X. Dual-Channel Supply Chain Coordination with Loss-Averse Consumers. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2023, 2023, 3172590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, M.A.; Truong, H.T.; Sonobe, T. COVID-19, Food Insecurity and Panic Buying Behavior: Evidence from Rural Bangladesh. Food Secur. 2025, 17, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, Y.; Jin, S.; Yan, X. Strategic Buyer Stockpiling in Supply Chains under Uncertain Product Availability and Price Fluctuation. Omega 2025, 133, 103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for retailers. Int. J. Retail. Distr. Manag. 2021, 49, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, I.G.; Balakrishnan, B.P.K.D.; Ting, H. Does Sustainable Consumption Matter? Consumer Grocery Shopping Behaviour Andthe Pandemic. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 507–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, M.; Kumar, N.; Rao, R. Consumer Stockpiling and Competitive Promotional Strategies. Mark. Sci. 2014, 33, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, C.; Park, S.; Kang, J. Panic Buying: Modeling What Drives It and How It Deteriorates Emotional Well-Being. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2021, 50, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cham, T.H.; Cheng, B.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Cheah, J.H. Should I Buy or Not? Revisiting the Concept and Measurement of Panic Buying. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 19116–19136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, K.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Li, K.X. The Psychological Causes of Panic Buying Following a Health Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S.; Potts, K.E.; Laylavi, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y. A Discussion of Irrational Stockpiling Behaviour during Crisis. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2020, 1, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R.; Jaiswal, D.; Thaichon, P. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motives: Panic Buying and Impulsive Buying during a Pandemic. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayah, N.; Hariasih, M. Panic Buying, Trust Issue, Impulse Buying on Purchase Intensity on the Shopee Marketplace During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Indones. J. Innov. Stud. 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, S.; Teramoto, K. A Dynamic Model of Rational “Panic Buying”. Quant. Econ. 2024, 15, 489–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntontis, E.; Vestergren, S.; Saavedra, P.; Neville, F.; Jurstakova, K.; Cocking, C.; Lay, S.; Drury, J.; Stott, C.; Reicher, S.; et al. Is it really "panic buying"? Public perceptions and experiences of extra buying at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K. Where Is the Panic in “Panic Buying”? Consumer Purchases at the Outset of the COVID Pandemic. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 2024, 42, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Consumer Panic Buying: Realizing Its Consequences and Repercussions on the Supply Chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D. Supply Chain Resilience: Conceptual and Formal Models Drawing from Hormone System Analogy. Omega 2023, 127, 103081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.; Kar, S.; Kabir, R. Panic Buying: Perspectives and Prevention; SpringerBriefs in Psychology; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, G.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. The Determinants of Panic Buying during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, C.; Quach, S.; Thaichon, P. Antecedents and Consequences of Panic Buying: The Case of COVID-19. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X.; Yuen, K.F. What Influences Panic Buying Behaviour? A Model Based on Dual-System Theory and Stimulus-Organism-Response Framework. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avi Herbon, K.K. Apportioning Limited Supplies to Competing Retailers under Panic Buying and Associated Consumer Traveling Costs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 162, 107775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, S.; Rafiee, M.; Weber, G.W. Analyzing the Impact of Panic Purchasing and Customer Behavior on Customer Purchasing Decisions and Retailer Strategies during Disruption. In Annals of Operations Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Narasimhan, R.; Kim, M.K. Retailer’s Sourcing Strategy under Consumer Stockpiling in Anticipation of Supply Disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3615–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, V.; Mat Roni, S.; Jie, F. Supply Chain Insights from Social Media Users’ Responses to Panic Buying during COVID-19: The Herd Mentality. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 290–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M. Do Social Media Platforms Develop Consumer Panic Buying during the Fear of COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwin, M.O.; Yang, S.; Sheldenkar, A.; Yang, X.; Lee, B.S.F. Assessing Consumer Rationality during a Pandemic: Panic Buying Behaviours and Its Association with Online Social Media Discourse. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2024, 13, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.C.; Westbrock, B.; Hoegen, H. A Simple Model of Panic Buying. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2023, 216, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, S.; Akamatsu, N.; Mizuno, M. Consumer Panic Buying: Understanding the Behavioral and Psychological Aspects. Int. J. Mark. Distrib. 2022, 5, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Junior, I.; Yoshizaki, H.T.Y.; Saraiva, F.A.; Bruno, N.d.C.; da Silva, R.F.; Hino, C.M.; Aguiar, L.L.; de Ataide, I.M.F. Panic Buying Behavior Analysis According to Consumer Income and Product Type during COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, C.; Chung, W.Y. Changes in Consumption Patterns during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analyzing the Revenge Spending Motivations of Different Emotional Groups. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WANG, H.H.; HAO, N. Panic Buying? Food Hoarding during the Pandemic Period with City Lockdown. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, J.M.; Flodén, J.; Woxenius, J. Grocery Hoarding in Sweden during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Consequences for Logistics. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2025, 59, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.; Boulaksil, Y.; Ghoudi, K.; Hamdouch, Y. Simplicity or Flexibility? Dual Sourcing in Multi-Echelon Systems under Disruption. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2025, 14, 100333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudoran, A.A.; Thomsen, C.H.; Thomasen, S. Understanding Consumer Behavior during and after a Pandemic: Implications for Customer Lifetime Value Prediction Models. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174, 114527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M.; Nandy, P.; Aswin Winardi, M.; Chen, Y.; Le Monkhouse, L.; Dominique-Ferreira, S.; Stantic, B. Relevant, or Irrelevant, External Factors in Panic Buying. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rune, K.T.T.; Keech, J.J.J. Is It Time to Stock up? Understanding Panic Buying during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Aust. J. Psychol. 2023, 75, 2180299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Cai, X.; He, D. Salience and Medication Panic Buying. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2025, 234, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Leong, J.Z.E.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X. Panic Buying during COVID-19: Survival Psychology and Needs Perspectives in Deprived Environments. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 62, 102421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zoubi, S.; Gharaibeh, L.; Jaber, H.M.; Al-Zoubi, Z. Household Drug Stockpiling and Panic Buying of Drugs During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Study From Jordan. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 813405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.B.; Kuo, H.T. Dual Speculative Hoarding: A Wholesaler-Retailer Channel Behavioral Phenomenon behind Potential Natural Hazard Threats. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 44, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermes, A. Information Overload and Fake News Sharing: A Transactional Stress Perspective Exploring the Mitigating Role of Consumers’ Resilience during COVID-19. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.S.; Mamun, M.R.; Saif-Ur-Rahman, K.M.; Rabby, A.A.; Zakaria, A. A Qualitative Exploration of Purchasing, Stockpiling, and Use of Drugs during the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Urban City of Bangladesh. Public Health Pract. 2024, 7, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Pappas, I.O.; Metri, B.; Hughes, L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Fake News on Facebook and Their Impact on Supply Chain Disruption during COVID-19. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 327, 683–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, S.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Kar, A.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Giannakis, M. How Did Online Misinformation Impact Stockouts in the E-Commerce Supply Chain during COVID-19—A Mixed Methods Study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 267, 109064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, H.; Zhang, H. Understanding Consumer Panic Buying Behaviors during the Strict Lockdown on Omicron Variant: A Risk Perception View. Sustainability 2022, 14, 17019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwah, M.W.N.; Nor Azila, M.N. The Role of Perceived Scarcity and Anxiety on Panic Buying Behaviour Among Consumers in the United Arab Emirates. J. Manag. World 2025, 2025, 966–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulis, A.; Theodoridis, P.; Chatzopoulou, E. Sustainable Brand Resilience: Mitigating Panic Buying through Brand Value and Food Waste Attitudes Amid Social Media Misinformation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Gomes, L.M.; Azab, N.; de Moraes Souza, J.G.; Sorour, M.K.; Kimura, H. Panic Buying and Fake News in Urban vs. Rural England: A Case Study of Twitter during COVID-19. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 193, 122598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jin, Y.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Identifying Emergence Process of Group Panic Buying Behavior under the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Yao, Q.; Chen, R.; Qian, R. Agent-Based Simulation Model of Panic Buying Behavior in Urban Public Crisis Events: A Social Network Perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 100, 105002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, S.M.Y.; Kar, S.K.; Marthoenis, M.; Sharma, P.; Hoque Apu, E.; Kabir, R. Psychological Underpinning of Panic Buying during Pandemic (COVID-19). Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, C.; Chu, C.; Yang, J. “If You Don’t Buy It, It’s Gone!”: The Effect of Perceived Scarcity on Panic Buying. Electron. Res. Arch. 2023, 31, 5485–5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; Islam, A.N.; Farooq, A.; Dhir, A. Unusual Purchasing Behavior during the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Stimulus-Organism-Response Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Tan, L.S.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X. Social Determinants of Panic Buying Behaviour amidst COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Perceived Scarcity and Anticipated Regret. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, N.A.; Nazri, M.A.; Ali, M.H.; Alam, S.S. The Panic Buying Behavior of Consumers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Examining the Influences of Uncertainty, Perceptions of Severity, Perceptions of Scarcity, and Anxiety. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. Understanding and Managing Pandemic-Related Panic Buying. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 78, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Alharthi, M.; Albarrak, M.; Aggarwal, S. Saudi Millennials’ Panic Buying Behavior during Pandemic and Post-Pandemic: Role of Social Media Addiction and Religious Values and Commitment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothilingam, P.; Kalaivani, Y. How Pandemic Has Influenced the Purchasing Behaviour of Consumers. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B.L. Pandemic Panic and Retail Reconfiguration: Consumer and Supply Chain Responses to COVID-19. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2021, 113, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Shukla, N.; Agarwal, R.; Taghikhah, F. Managing Panic Buying-Related Instabilities in Supply Chains: A COVID-19 Pandemic Perspective. IFAC-Papersonline 2022, 55, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aflaki, A.; Swinney, R. Inventory Integration with Rational Consumers. Oper. Res. 2021, 69, 1025–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Q. Developing Supply Chain Resilience through Integration: An Empirical Study on an e-Commerce Platform. J. Oper. Manag. 2023, 69, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, Y.; Lai, C.M.; Hamm, A.; Takagi, S.; Sekimoto, Y. Do Open Data Impact Citizens’ Behavior? Assessing Face Mask Panic Buying Behaviors during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeleke, A. Understanding Consumer Behaviour and Its Impact on Supply Chain Planning. 2024. Available online: https://businessday.ng/columnist/article/understanding-consumer-behaviour-and-its-impact-on-supply-chain-planning/ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Nawarathne, N.; Galdolage, B. Do People Change Their Buying Behavior during Crises? Insights from the COVID-19 Pandemic in Sri Lanka. Asian J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Intertemporal Pricing and Consumer Stockpiling. Oper. Res. 2010, 58, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Ma, Y.; He, Z.; Che, A.; Huang, Y.; Xu, J. The Impact of Consumer Price Forecasting Behaviour on the Bullwhip Effect. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 6642–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Smetana, S.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Hossaini, S.M.; Heinz, V.; Kircher, C. The Impact of Corona Pandemic on Consumer’s Food Consumption. J. Consum. Prot. Food Saf. 2021, 16, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, N.; Wang, H.H.; Zhou, Q. The Impact of Online Grocery Shopping on Stockpile Behavior in Covid-19. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.J.; Liu, S.S.; Huang, G.Q.; Ng, C.T. How Does Consumer Quality Preference Impact Blockchain Adoption in Supply Chains? Electron. Mark. 2025, 35, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohale, V.; Verma, P.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ambilkar, P. COVID-19 and Supply Chain Risk Mitigation: A Case Study from India. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P. Strategies for Managing the Impacts of Disruptions during COVID-19: An Example of Toilet Paper. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2020, 21, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): A Review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghikhah, F.; Voinov, A.; Shukla, N.; Filatova, T. Exploring Consumer Behavior and Policy Options in Organic Food Adoption: Insights from the Australian Wine Sector. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 109, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Shukla, N.; Agarwal, R.; Taghikhah, F. Supply Chain Resilience Initiatives and Strategies: A Systematic Review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 170, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Yao, J. Intertwined Supply Network Design under Facility and Transportation Disruption from the Viability Perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2513–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Venkatesh, M. Manufacturing and Service Supply Chain Resilience to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Lessons Learned from the Automobile and Airline Industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeagu, C.N.; Reed, D.S.; Sun, L.; Colontonio, M.M.; Rezayev, A.; Ghaffar, Y.A.; Kaye, R.J.; Liu, H.; Cornett, E.M.; Fox, C.J.; et al. Principles of Supply Chain Management in the Time of Crisis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 35, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, S.J.; Diaz, M.; Arnaboldi, M. Understanding Panic Buying during COVID-19: A Text Analytics Approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 169, 114360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liren, X.; Junmei, C.; Mingqin, Z. Research on Panic Purchase’s Behavior Mechanism. Innov. Manag. 2012, 1332–1337. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Research+on+Panic+Purchase%E2%80%99s+Behavior+Mechanism&btnG= (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Nguyen, A.; Pellerin, R.; Lamouri, S.; Lekens, B. Managing Demand Volatility of Pharmaceutical Products in Times of Disruption through News Sentiment Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, S.; Maruyama, A.; Luloff, A.E. Analysis of Consumer Behavior in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Food Syst. Res. 2012, 18, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, M.; Neal, T. Consumer Panic in the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Econom. 2021, 220, 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octaviani, A.; Akhrani, L.A. COVID-19: Assessing the Role of Citizen Trust to Governments on Panic Buying Behavior in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Khazanah J. Mhs. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Paul, S.K.; Agarwal, R.; Shukla, N.; Taghikhah, F. A Viable Supply Chain Model for Managing Panic-Buying Related Challenges: Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 3415–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, B.d.F.O.; Fontainha, T.C.; Leiras, A. Looking Back and Forward to Disaster Readiness of Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 27, 1569–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Mejia-Argueta, C. Mapping Research in Logistics and Supply Chain Management during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; De Souza, R. Supply Chain Resilience Enhancement Strategies in the Context of Supply Disruptions, Demand Surges, and Time Sensitivity. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Dresner, M.; Li, G.; Mantin, B. Stocking up on Hand Sanitizer: Pandemic Lessons for Retailers and Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macau, F.R. ‘Panic-buying’ Events Are the New Normal; Here’s How Supply Chains Have Adapted. 2021. Available online: https://theconversation.com/panic-buying-is-the-new-normal-how-supply-chains-have-adapted-154362 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Aljuneidi, T.; Punia, S.; Jebali, A.; Nikolopoulos, K. Forecasting and Planning for a Critical Infrastructure Sector during a Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from a Food Supply Chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 317, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.C.; Raj, P.V.R.P. Product Substitution with Customer Segmentation under Panic Buying Behavior. Sci. Iran. 2020, 27, 2514–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbon, A.; Kogan, K. Scarcity and Panic Buying: The Effect of Regulation by Subsidizing the Supply and Customer Purchases during a Crisis. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 318, 251–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Girotra, K.; Netessine, S. Recovering Global Supply Chains from Sourcing Interruptions: The Role of Sourcing Strategy. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 846–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.C.; Raj, P.V.R.P.; Yu, V. Product Substitution in Different Weights and Brands Considering Customer Segmentation and Panic Buying Behavior. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 77, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, M.; Neise, T.; She, W.; Taniguchi, M. Conversion Strategy Builds Supply Chain Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Typology and Research Directions. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2023, 17, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Q. Production Change Optimization Model of Nonlinear Supply Chain System under Emergencies. Sensors 2023, 23, 3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, D.; Arvidsson, A.; Saiah, F. Resilient Supply Management Systems in Times of Crisis. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dong, C. Government Regulations to Mitigate the Shortage of Life-Saving Goods in the Face of a Pandemic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 942–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joong Lee, D.; Zhang, M. Tackling Panic Buying During COVID-19: A Case Study of the Public Procurement Measures on Face Masks from South Korea. Am. J. Health Behav. 2024, 48, 1589–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, O.; Amaral, J.C.; Holguin-Veras, J. Willingness to Limit “Panic Buying” during the COVID-19 Crisis. Transp. Res. Part -Policy Pract. 2025, 191, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, S.; Rafiee, M.; Weber, G.W. Disruption, Panic Buying, and Pricing: A Comprehensive Game-Theoretic Exploration. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaya, Y.; Krishna, V. Panics and Prices. J. Econ. Theory 2024, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Salido, J.D.; Gagnon, E. Small Price Responses to Large Demand Shocks. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2015, 18, 792–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzamil, A.Z.A.; Pyeman, J.; binti Mutalib, S.; Azma binti Kamaruddin, K.; binti Abdul Rahman, N. Enabling Retail Food Supply Chain, Viability and Resilience in Pandemic Disruptions by Digitalization—A Conceptual Perspective. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. 2025, 7, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoek, R. Research Opportunities for a More Resilient Post-COVID-19 Supply Chain–Closing the Gap between Research Findings and Industry Practice. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y. Retailer’s Emergency Ordering Policy When Facing an Impending Supply Disruption. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, R.; Gaudenzi, B. Impacts and Supply Chain Resilience Strategies to Cope with COVID-19 Pandemic: A Literature Review. In Supply Chain Resilience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovezmyradov, B. Product Availability and Stockpiling in Times of Pandemic: Causes of Supply Chain Disruptions and Preventive Measures in Retailing. In Annals of Operations Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J.D.; Dogan, G. “I’m Not Hoarding, I’m Just Stocking up before the Hoarders Get Here.”: Behavioral Causes of Phantom Ordering in Supply Chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 39, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Kalantari, H.D.; Perera, C.R. Commercial Value of Panic Buying and Its Marketing Implications. J. Consum. Behav. 2024, 23, 2201–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.B.; Choi, T.M. Proactive Hoarding, Precautionary Buying, and Postdisaster Retail Market Recovery. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 4263–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Academic Platform | Keywords | Number Records |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | Supply disruption and panic buying | 109 |

| Web of Science | Panic buying and supply chain management | 145 |

| Web of Science | Managing consumer panic-buying behavior | 110 |

| Total after removing duplicates | 313 | |

| ScienceDirect | Supply disruption and panic buying and supply chain management | 958 |

| Google Scholar | Supply disruption and panic buying and supply chain management | 2260 |

| Journal Name | Number of Publications |

|---|---|

| Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | 11 |

| International Journal of Production Research | 5 |

| International Journal of Production Economics | 3 |

| Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization | 3 |

| Sustainability | 3 |

| Annals of Operations Research | 3 |

| International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | 3 |

| Omega–The International Journal of Management Science | 3 |

| Research Method | Count | Percentage | Representative Papers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical | 59 | 44.03% | [22] Panic buying in the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-country examination. (Survey/social media data analysis) |

| [23] Impact of COVID-19 on impulse buying behavior. (Retail panel data econometric model) | |||

| Systematic Review | 30 | 22.39% | [11] Panic buying research: A systematic literature review. (PRISMA framework) |

| [15] Supply chain resilience during pandemics. (Bibliometric analysis) | |||

| Game Theory | 17 | 12.69% | [24] Retailer hoarding in emergency situations: A game-theoretic analysis. (Nash equilibrium model) |

| [25] Managing panic buying with Bayesian persuasion. (Signaling game) | |||

| Optimization | 17 | 12.69% | [26] Production recovery under COVID-19. (Stochastic dynamic programming) |

| [27] Dual-channel supply chain coordination. (Nonlinear programming) | |||

| Others | 11 | 8.21% | [1] The anatomy of panic buying. (Conceptual framework) |

| [28] Food insecurity and panic buying. (Case study) |

| Author (Year) | Research Focus | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Islam et al. [22] | Panic buying across countries during COVID-19 |

|

| Gangwar et al. [32] | Promotional strategies and rational stockpiling |

|

| Li et al. [29] | Strategic stockpiling under price fluctuations |

|

| Xu et al. [21] | Retailer ordering under panic buying |

|

| Zheng et al. [19] | Social learning effects and inventory management |

|

| Ivanov [43] | Supply chain resilience modeling |

|

| Yuen et al. [35] | Psychological mechanisms of panic buying |

|

| Arafat et al. [44] | Panic buying during natural disasters |

|

| Factors | Key Examples and Findings | Sample References |

|---|---|---|

| Information Asymmetry |

| [28,35,48,60,64,65] |

| Social Influence |

| [19,49,66,67,68,69,70,71] |

| Network Diffusion |

| [30,35,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] |

| Individual Psychology |

| [26,35,44,74,75,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] |

| Strategy | Concrete Measures | Sample References | Situations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Intervention and Calm Restoration | Encourage community engagement to enhance self-efficacy. | [108] | Panic buying driven by feelings of loss of control. |

| Transparency and Rational Guidance | Use “Purchase As Needed” labels to nudge behavior. | [109] | |

| Publish information accurately and transparently. | [42,108] | ||

| Avoid media rumors of shortages. | [111] | Real-time information spreading on social media, causing panic buying. | |

| Encourage consumers to limit their purchases of critical supplies through the use of trusted agents, such as firefighters. | [130] | ||

| Flexible Supply and Adjustments | Dynamic production capacity adjustment. | [21,89,135] | Low price elasticity of demand. |

| Production conversion and expansion; digitization. | [125,126] | High emergency demand. | |

| Taking trans-shipment actions. | [127] | Demand surge in specific areas. | |

| Priority Management | Customer segmentation for priority access. | [121] | Consumer behavior shows differentiation; protect disadvantaged groups. |

| Logistics and Supplier Networks | Build emergency procurement channels. | [9,136] | Disaster prevention and post-disaster recovery period. |

| Diversify supplier networks to reduce dependency risks. | [46] | ||

| Government Actions | Implement price controls during crises. | [9] | For high-demand products where market mechanisms fail. |

| Establish joint emergency reserves. | [44] | Disaster prevention and post-disaster recovery period. Information asymmetry. | |

| Issue authoritative supply chain statements. | [25,108] | ||

| Increase public procurement. | [129] | ||

| Retailer Measures | Adopt dynamic pricing and real-time inventory platforms. | [10,46] | High demand and consumers’ perceived risk. |

| Pre-stock key goods to curb early panic. | [19,112] | In times of disaster warning or at the early stage of occurrence, demand forecasting is easy, and products are easy to store. | |

| Implement purchase limits or quotas. | [10,137] | Demand is surging, inventory is insufficient, and panic is intense. |

| Dimension | Specific Impacts | Concrete Expression | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain Performance | Reduced efficiency | Demand –response lags. Obstructed global circulation. | [45,51] |

| Cost increase | Rising shortage costs, inventory costs, and transportation costs. Increased bullwhip effect. | [89,138,139] | |

| Resource mismatch | Overstocking leads to waste of resources; irrational demand leads to waste of energy and raw materials. | [45,89] | |

| Consumer Welfare | Economic burden | Price increases. Additional cost increases. Wasteful spending. | [42,89,114] |

| Psychological pressure | Social anxiety spreads to fuel panic. Consumers’ long-term trust in markets collapses. | [51,89] | |

| Social inequality | Difficulty in accessing necessities for disadvantaged groups. Policies (limiting purchases/high prices) disproportionately affect low-income populations. | [45,138] | |

| Two-way Interaction Mechanism | The “shortage→ rush→shortage” cycle; the “panic →shortage→ repeat panic" cycle | Supply chain disruptions trigger consumer panic buying, further exacerbating inventory pressures. | [45] |

| Interaction between stocking, pricing, and panic buying | Adjusting price may balance the supply and demand but need to avoid the vicious circle of “panic –> price increase –>more panic”. Active stockpiling may temporarily ease supply pressures, but excessive stockpiling prolongs recovery times. | [10,89] |

| Research Gap | Specific Direction | Recommended Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Model Validation | Develop and validate analytical models to assess intervention policies (e.g., stochastic inventory models for shortage cost analysis, agent-based simulations for demand estimation, and game-theoretic frameworks for pricing–quota trade-offs) | Mathematical modeling combined with empirical data calibration; simulation and optimization |

| Digital Technology Integration | Leverage AI for real-time demand forecasting during panic spikes and blockchain to enhance supply chain transparency and trust among stakeholders | Agent-based simulation integrating IoT data; case studies of pilot implementations in retail or manufacturing sectors |

| Cross-cultural Comparative Studies | Compare panic buying thresholds, behavioral drivers (e.g., loss aversion), and policy effectiveness across diverse cultural and regulatory contexts | Multi-country survey data; comparative case studies controlling for exogenous factors |

| Interdisciplinary Collaboration | Integrate behavioral science with supply chain modeling to design behavior-aware inventory and pricing strategies | Mixed methods combining laboratory experiments, system dynamics modeling, and optimization |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, R.; Gu, B.; Yin, S.; Lai, K.K. Supply Chain Management in Times of Supply Disruption Risk and Consumer Panic Buying: A Systematic Review. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213449

Zheng R, Gu B, Yin S, Lai KK. Supply Chain Management in Times of Supply Disruption Risk and Consumer Panic Buying: A Systematic Review. Mathematics. 2025; 13(21):3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213449

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Rui, Bowen Gu, Shiqi Yin, and Kin Keung Lai. 2025. "Supply Chain Management in Times of Supply Disruption Risk and Consumer Panic Buying: A Systematic Review" Mathematics 13, no. 21: 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213449

APA StyleZheng, R., Gu, B., Yin, S., & Lai, K. K. (2025). Supply Chain Management in Times of Supply Disruption Risk and Consumer Panic Buying: A Systematic Review. Mathematics, 13(21), 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213449