1. Introduction

The efficiency of storage allocation and order picking for fresh products is a critical determinant of overall supply chain performance, impacting product preservation, logistics cost control, and end-user delivery timeliness [

1,

2]. As traditional warehousing paradigms evolve toward intelligent, fine-grained management, the processes for storing and picking fresh products demand greater dynamic adaptability. Modern fresh e-commerce platforms, in the process of handling large volumes of orders and high-frequency deliveries, urgently need a flexible and responsive warehouse scheduling mechanism. In this context, intelligent warehousing systems are gradually being introduced into actual operations, the essence of which is to achieve coordinated control over aspects like slotting, picking paths, and personnel scheduling through algorithmic optimization.

Within intelligent warehousing systems, the order picking process for fresh products is characterized by a high degree of operational flexibility, manifested in several key areas: (1) Multiple Routing Options: A single order can be fulfilled through various picking routes, the optimality of which must be assessed based on the real-time warehouse layout and order prioritization. (2) Flexible Item Sequencing: For certain orders, the sequence of item collection is adjustable, with different sequences significantly impacting overall picking efficiency. (3) Dynamic Task Allocation: Picking tasks can be dynamically distributed among multiple pickers to balance operational workloads. The inherent perishability and short shelf-life of fresh products impose additional constraints; their storage locations must not only satisfy temperature control requirements but also be strategically positioned near exits or packing stations to minimize dwell time and energy consumption. The scope for optimizing the storage allocation of fresh products is substantially greater than for conventional goods, involving a more complex set of decision variables and constraints.

Therefore, the core challenge in fresh produce warehousing lies in the joint optimization of storage location assignment and order picking routing. The primary optimization objectives focus on minimizing picking path costs and optimizing the warehouse storage location layout to meet the aforementioned complex requirements. Simultaneously, considering the actual operational priorities of different warehouses, the relative weights of secondary objectives—such as ongoing energy costs for temperature control, additional operational costs incurred by ensuring FIFO (First-In-First-Out), and order picker task scheduling costs—are dynamically configured and adjusted entirely by warehouse administrators based on actual management needs.

In recent years, the optimization of storage allocation and order picking operations has emerged as a prominent area of research. Hall et al. [

3] enhanced picking efficiency by comparing various picking strategies and optimizing warehouse layouts. Petersen et al. [

4] investigated the impact of three operational decisions—order picking, storage assignment, and routing—on picker travel distance, concluding that category-based or capacity-based storage strategies yield savings comparable to order batching but are less sensitive to variations in average order size. Early research on fresh product warehousing mainly focused on inventory management. Nahmias [

5] reviewed the relevant literature on the problem of determining appropriate ordering policies for perishable inventory with a fixed lifetime and inventory subject to continuous exponential decay. Piramuthu et al. [

6] integrated product quality information into management frameworks to enhance retailer profitability, while Bai et al. [

7] formulated a single-period inventory and shelf-space allocation model specifically for fresh agricultural produce. They used an improved Generalized Reduced Gradient (GRG) algorithm for solving it. Lin et al. [

8] proposed a mathematical model for the coordinated optimization of slotting and AGV (Automated Guided Vehicle) paths, and used an improved genetic algorithm to achieve it. The experimental results verified the effectiveness and stability of the proposed storage allocation optimization algorithm.

With the rise of fresh e-commerce, the complexity of storage allocation and picking has increased significantly, prompting researchers to explore more intelligent optimization algorithms. In the past few decades, more than a dozen different heuristic algorithms have been developed [

9], some of which are inspired by biological habits, such as genetic algorithms, ant colony algorithms, bat algorithms, firefly algorithms, and so on. Among them, the genetic algorithm has been used to solve complex problems in real life, such as in energy [

10,

11], logistics [

12], medicine [

13], robotics, and other engineering fields [

14,

15].

Focusing on fresh produce application scenarios, Azadeh et al. [

16] formulated a transshipment inventory-routing problem for a single perishable product, which they solved using a genetic algorithm. Similarly, Hiassat et al. [

17] addressed a location-inventory-routing model for perishable goods, employing a genetic algorithm enhanced with a novel chromosome representation and a local search heuristic. Concurrently, hybrid optimization algorithms have offered a new paradigm for tackling these problems. Li et al. [

18] designed a hybrid genetic algorithm based on information entropy and game theory to mitigate the tendency of traditional GAs to converge to local optima. Zhang et al. [

19] proposed a hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (HPSO) algorithm for process planning, which replaces the standard particle position and velocity update rules with genetic operators. Addressing the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP), He et al. [

20] developed an Improved Genetic-Simulated Annealing Algorithm (IGSAA) to counteract the premature convergence of GA and the slow convergence of Simulated Annealing (SA). Liu et al. [

21] introduced a hybrid GA-PSO algorithm to optimize a five-parameter BRDF (Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function) model, demonstrating its superior accuracy and convergence speed through comparative experiments on different materials. Although these methods show potential for solving complex problems, some studies have shown that their algorithmic robustness is susceptible to some strong constraints in fresh product scenarios.

In order to overcome the defects of a single algorithm, existing research has turned to hybrid algorithms that incorporate the advantages of multiple algorithms: Heidari et al. [

22] proposed the HHO-VNS framework which innovatively combines the global exploration capability of Harris Hawk Optimization algorithm with Variable Neighborhood Search, but its fixed neighborhood switching mechanism still exists as a bottleneck of searching efficiency in some complex problems; Although the GA-ALNS (Genetic Algorithm-Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search) two-stage architecture developed by Ropke et al. [

23] effectively improves the solution space traversal, there is still room for further improvement in the setting of the core parameters of the algorithm. Meanwhile, the above deficiencies are further amplified in fresh storage scenarios, which reveals the core challenge faced by existing studies in fresh scenarios: namely, the lack of modeling level. Some studies have not yet established a joint storage-picking optimization system that integrates temperature control and time constraints, and there is an urgent need to build a modeling system that covers cargo storage allocation, dynamic picking path planning, and human resource scheduling.

In order to effectively fill this research gap, the algorithm design needs to satisfy the above two core challenges of multi-constraints and dynamic equilibrium ability at the same time. In view of this goal, Particle Swarm algorithm (PSO) is often chosen as the mainstream solution algorithm because of its global exploration advantage, especially suitable for solving the high-dimensional coupling characteristics of the solution space triggered by the large-scale dynamic order scheduling, multi-temperature zones coordinated control, and strong time constraints in fresh food. The experimental results verified the effectiveness and stability of the proposed storage allocation collaborative optimization algorithm, where the traditional heuristic algorithms are easily limited by the local search capability. However, the application form of PSO is still limited by inherent defects such as premature convergence risk, exploration–exploitation behavior imbalance and static parameter dependence. Therefore, this study constructs a Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing algorithm (PS-GSA), whose core motivation is to fully use the complementary mechanisms of these algorithms, i.e., the global exploration of PSO, the cross-variance mechanism of GA, and the Metropolis criterion of SA, to match with the scenario of storage allocation for fresh products. We propose the Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing algorithm (PS-GSA), whose core innovativeness is embodied in the design of the three-level co-optimization mechanism.

The main contributions of this study can be summarized in four points:

First, this study pioneers a novel hierarchical and synergistic optimization framework. Unlike conventional hybrid algorithms that merely combine operators, our proposed PS-GSA establishes a distinct hierarchical relationship where Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) acts as a high-level global strategist. The PSO algorithm does not directly manipulate the solution but guides the evolutionary trajectory of the entire population within the lower-level Genetic Algorithm (GA). This primary architecture effectively leverages PSO’s strengths in rapid global convergence to prevent the GA population from prematurely stagnating in local optima, thus creating a more powerful and purposeful exploration of the solution space.

Second, we introduce a sophisticated dynamic mechanism to explicitly balance exploration and exploitation. This is achieved through the synergistic integration of Simulated Annealing (SA) and Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS). The Metropolis acceptance criterion of SA is employed not as a standalone search algorithm, but as a probabilistic gateway that adaptively controls the trade-off between accepting superior solutions and exploring potentially inferior but promising regions. This process is further enhanced by a VNS-based local search, which is triggered to intensify the search in promising areas. This dual-component mechanism allows the algorithm to dynamically shift its behavior from broad exploration in the early stages to deep exploitation in the later stages, effectively addressing the premature convergence issue common in complex combinatorial optimization problems.

Third, this study contributes a highly comprehensive cost model specifically tailored to the unique operational challenges of fresh e-commerce. Moving beyond the traditional objectives of minimizing travel distance and optimizing storage assignments, our model integrates critical, real-world factors pertinent to the fresh product supply chain. These include the energy consumption costs associated with different temperature zones (ambient, refrigerated, and frozen), the layout optimization costs to ensure logical zoning, and a picker scheduling cost objective designed to balance workload among workers. By formulating this multi-dimensional objective function, our research provides a more holistic and practically relevant decision-making framework for warehouse managers in the fresh e-commerce sector, enabling them to make more informed trade-offs between efficiency, cost, and operational sustainability.

Fourthly, we rigorously evaluate the practical applicability and robustness of our model through systematic trade-off and sensitivity analyses. This investigation not only reveals the quantitative trade-offs among different strategic operational objectives but also confirms the solution’s resilience to uncertainties in decision-maker preferences, providing a solid foundation for the model’s deployment in complex, real-world environments.

Comparisons with similar studies also reveals the above advantages. For example, Pan et al. [

24] used a genetic algorithm combined with space overflow correction mechanism to optimize the storage allocation of cargo for the traditional pick-and-pass warehouse system, which only focuses on the workload balance of multi-pickers and the reduction of SKU (Stock Keeping Unit) out-of-stock, which only applies to small- and medium-sized general warehouses, and does not involve the core characteristics of perishability and temperature control requirements of fresh food. In contrast, this study achieves an all-round breakthrough for fresh storage, not only constructing a three-zone temperature control system of ambient/chilled/frozen, but by clarifying the capacity differentiation of cargo space, introducing the constraints of odor phasing (setting the minimum storage distance according to the intensity of the odor to prevent contamination) and the penalty cost of FIFO (quantifying the priority of storage demand for the products first stored by the time system of the storage system), accurately covering the pain points of fresh quality assurance through the AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) to determine the weights, the picking path, cargo layout deviation, energy consumption and carbon emissions, FIFO penalty and personnel scheduling of the five costs into a multi-dimensional model, not only to retain the other side of the concern of the efficiency of the target, but also to add new fresh products specific to protect product quality and energy-saving goals. Similarly, Zhang et al. [

25] focus on non-traditional warehouse layouts such as Flying-V and Fishbone, and adopt the fireworks algorithm (FWA) with adaptive explosion and selection strategy to optimize the picking efficiency and shelf stability as the dual-objective optimization, which can improve the energy efficiency by shortening the picking distance, but it still belongs to the category of general-purpose warehousing, and cannot consider the temperature control dependence of the fresh food (e.g., high energy consumption of the freezer area), perishability-induced storage priority difference and personnel scheduling synergy needs, and did not quantify the matching relationship between multi-objective weights and the actual needs of fresh food. In this paper, the optimization of fresh storage is based on the characteristics of fresh storage, which not only considers the rationality of the warehouse layout but also clarifies the temperature control matching rules of products and cargo space, quantifies the energy consumption cost of different temperature control zones, and solves the problem of high energy consumption of fresh cold chain control that is neglected by the previous one, but also reduces the expenditure of the cold chain and guarantees the product quality of fresh products through energy consumption control.

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows:

Section 2 introduces the optimization model and constraint settings for the fresh product storage allocation;

Section 3 elaborates on the design of the proposed optimization algorithm;

Section 4 presents the simulation process and results evaluation of a practical case study; and

Section 5 summarizes the research contributions and looks forward to future work.

2. Mathematical Model

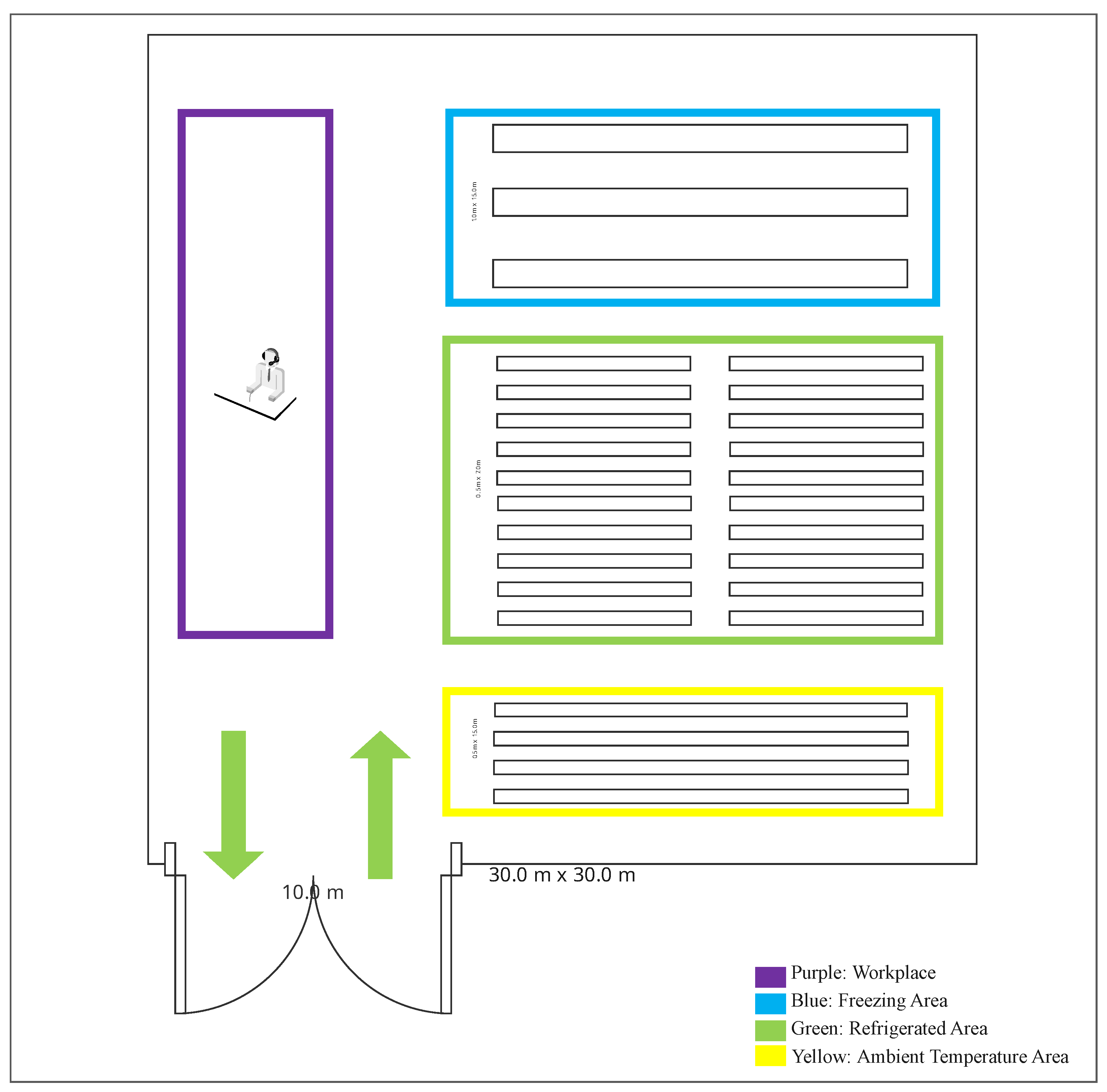

We consider a fresh product warehouse composed of distinct temperature-controlled zones, as depicted in

Figure 1. The storage area is partitioned into three specific zones: ambient, refrigerated, and frozen. Each storage location is pre-assigned to a temperature zone, has a width of 0.5 m, and is subject to a fixed capacity

. For instance, locations in the frozen zone can hold up to five units of an identical product, whereas locations in other zones have a capacity of one. Order pickers employ a discrete picking (picker-to-parts) strategy, where each picking tour originates and terminates at a single depot (designated as

) after visiting all required item locations. To accommodate the perishability, stringent temperature controls, and environmental considerations associated with fresh products, an efficient warehouse management system must simultaneously pursue the following objectives:

- (1)

Picker Routing Optimization: To minimize the total travel distance and time required to fulfill all orders.

- (2)

Storage Location Assignment Optimization: To assign products to locations as close as possible to their designated central storage points or the packing station, thereby facilitating First-In, First-Out inventory control and reducing picking times.

- (3)

Energy and Carbon Footprint Minimization: To assign higher energy cost coefficients to high-consumption zones (e.g., refrigerated and frozen areas) to ensure that the storage strategy minimizes total energy consumption and carbon emissions while satisfying both temperature and picking efficiency constraints.

- (4)

Workload Balancing: To optimally assign orders among pickers to minimize operational conflicts and route overlaps, balance workloads, and enhance overall collaborative efficiency.

Figure 1.

Warehouse layout plan.

Figure 1.

Warehouse layout plan.

The model considers a general fresh product warehouse layout organized as a three-dimensional grid, which can be adapted to various physical configurations. Let , , and denote the total number of rows, columns, and levels in the storage area, respectively. Each discrete storage location k is uniquely identified by a coordinate triplet , where , , and . The set of all storage locations is denoted by K. The set of pickers is denoted by , where is the total number of pickers. Each location k is pre-assigned to a specific temperature zone, represented by a numerical index , where is the set of all distinct temperature zones. Similarly, each product has a specific temperature requirement, denoted by an index . A workable storage assignment requires that a product m can only be stored in a location k if their temperature zone indices match (i.e., ). For the case study in this paper, we consider three distinct zones, thus , corresponding to the ambient, refrigerated, and frozen zones, respectively.

The storage capacity

depends on the zone, as defined by

Each product has a specific temperature requirement , a cumulative in-warehouse time of , and a designated central storage coordinate .

The set of orders is denoted by , where each order comprises a subset of products . The set of pickers is denoted by . Each order must be assigned to a single picker (where represents this assignment), and workloads should be balanced. All picking tours start from and return to the packing station, .

To calculate the picking path cost, the model first maps the three-dimensional storage location index

to two-dimensional planar coordinates

that reflect the physical layout of the warehouse aisles. The planar coordinates are functions of the row index

and column index

, while the level index

does not affect the travel distance in this picker-to-parts model, as horizontal travel along and between aisles makes up the primary component of the total path. The orthogonal grid layout of warehouse aisles renders Euclidean distance an inaccurate measure of a picker’s actual travel path. This study employs the Manhattan distance to calculate the travel distance between any two storage locations. For two locations,

k and

, with planar coordinates

and

, respectively, the Manhattan distance

is defined as

The model assumes a constant travel speed for pickers; therefore, the picking path cost (i.e., picking time) is directly proportional to the total travel distance. Operationally, the model supports order batching, allowing a picker to merge items from multiple orders into a single picking tour, with the total path length minimized by optimizing the pick sequence.

As for energy cost, each location k is associated with an energy cost parameter . The value is highest for the frozen zone, moderate for the refrigerated zone, and zero for the ambient zone.

The symbols and parameters used in the mathematical model are presented in

Table 1.

The decision variables for the mathematical model are presented in

Table 2.

The joint optimization model for fresh product storage allocation and picking efficiency proposed seeks to minimize a single, comprehensive objective function, which is formulated by aggregating five key cost components using a weighted sum method. These five cost components are picking path cost (

), storage layout deviation cost (

), FIFO penalty cost (

), energy and carbon emission cost (

), and picker scheduling cost (

). The total objective function of the model is formulated as follows:

Each cost component is detailed below:

- (1)

Picking Path Cost

For each order

, let

be the set of storage locations to be visited as follows:

Let

be the length of the shortest tour for picking order

j, starting from the depot

, visiting all locations in

and returning to

. The total picking path cost objective is then

represents the sum of travel distance costs for all orders.

- (2)

Storage Layout Deviation Cost

To penalize the deviation of product storage locations from their designated central locations, the following objective function is formulated as follows:

represents the total cost incurred from the sum of distances between each product’s assigned location and its central location.

- (3)

FIFO Penalty Cost

Upon receiving products, pickers scan barcodes to log entry information, including arrival time. Given the perishability and short shelf-life of fresh products, we analyze each product’s dwell time

and introduce a penalty term to ensure that items with earlier arrival times are stored closer to the depot:

Here, the coefficient is directly proportional to the product’s cumulative time in storage (a longer storage time results in a higher ), prioritizing it for picking.

- (4)

Energy and Carbon Emission Cost

To account for the operational energy consumption and carbon emissions of the temperature-controlled zones, an energy cost

is assigned to each location

k. The total storage energy cost is

- (5)

Picker Scheduling Cost

To quantify and penalize workload imbalance among pickers, the model incorporates a scheduling cost objective based on the variance of individual workloads. For each picker , let denote the subset of orders assigned to them. This set is formally defined based on the decision variable as . The workload for picker p, denoted as , is the sum of the travel distances for all orders in their assigned set: ,where is the set of orders assigned to picker p.

First, the average workload

across all pickers is calculated as follows:

The scheduling cost objective is the variance of the workloads among pickers, expressed as

This objective function drives the optimization toward a fair distribution of tasks among all pickers by minimizing the workload variance, achieving a balanced workload.

For in the multi-objective optimization model constructed in this study, the determination of the weight coefficients , and of each cost subcomponent is a key aspect that affects the decision preference of the final optimization scheme. To ensure the interpretability of weight assignment and flexibility in real-world applications, this study used the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to determine these weights. The reason for choosing AHP as the weight determination method is based on the following considerations: First, decision-making in warehouse management essentially involves trade-offs among multiple conflicting objectives (e.g., efficiency, cost, and quality), which highly depends on the experience and strategic preferences of the decision-makers (e.g., warehouse managers). Unlike purely objective methods, such as the entropy weight method that determines weights based solely on data dispersion, AHP is good at systematically converting such qualitative and subjective judgments into quantitative weights through pairwise comparison, and its structured hierarchical model is a natural fit with the “general objective-sub-objective” structure of this problem. Second, compared with other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods, AHP provides a mature Consistency Ratio (CR), which can quantify the reliability of the judgment logic, thus guaranteeing the reasonableness and robustness of weight allocation.

The application of AHP hierarchical analysis in this study follows the following steps: first, construct a hierarchical model. We decompose the optimization problem into a Goal Layer, i.e., “minimize the total operating cost”, and a Criteria Layer, i.e., five specific cost subcomponents: , , , , and . Second, the judgment matrix is constructed. We invite domain experts to compare each cost objective in the guideline layer two by two based on Saaty’s 1-9 scale to construct a judgment matrix A, so as to quantify the relative importance among the objectives. Third, calculate the weight vector and consistency test. By calculating the maximum eigenvalue () and its corresponding normalized eigenvector of the judgment matrix A, the weight vector of each cost item is obtained . Subsequently, the Consistency Index is calculated by the formula , and the Consistency Ratio is calculated by the formula , where n denotes the order of the matrix and represents the average random Consistency Index. Only when is the judgment matrix deemed to possess acceptable consistency, and its corresponding weight vector is valid.

It is worth emphasizing that the target preferences in this model are user-selectable rather than fixed. The specific weights used in the subsequent experiments. are derived from a judgment matrix constructed based on a typical operational scenario in which “order fulfillment timeliness” is the primary goal. Warehouse managers can reconstruct the judgment matrix according to specific business environments and strategic priorities to generate a set of customized weights that meet current needs. For example, the weight of can be significantly increased when energy prices are high, and the weight of can be further increased during the response to large-scale promotional activities.

Based on the above, the specific process of weight assignment using hierarchical analysis in this study is as follows: The initial step involves constructing the hierarchical model. The hierarchical model for this study comprises two levels: a Goal Layer and a Criteria Layer. The Goal Layer is defined as the optimization of total operational costs for fresh product storage allocation and picking, while the Criteria Layer consists of the five cost objectives under evaluation:, and .

The core of the AHP method is the use of pair-wise comparisons to transform qualitative judgments from decision-makers regarding the relative importance of criteria into a quantitative format [

26]. This study employs the Saaty 1–9 scale to construct the judgment matrix, with the scale’s definitions detailed in

Table 3.

Based on the high-timeliness requirements and the focus on major operational costs inherent in the fresh e-commerce case study, we established the following prioritization logic based on the data collected from managers:

First, the picking path cost () is identified as the most critical factor, as it directly dictates order fulfillment speed, which is central to ensuring rapid response times for fresh product orders. Second, the storage layout cost () is a strategic factor whose importance is second only to path cost; it supports rapid picking by optimizing the storage locations of high-turnover items. Subsequently, while product quality is vital, the substantial and continuous energy cost () associated with refrigerated and frozen zones represents a significant financial expenditure that requires stringent control. Under financial constraints, its priority is ranked higher than the FIFO penalty cost (). Finally, the picker scheduling cost (), which aims to balance internal workloads, is considered a secondary optimization objective relative to customer-facing efficiency metrics and major cost-control items.

Based on this analysis, the resulting judgment matrix A is presented in

Table 4.

Subsequently, the weight vector is calculated, and a consistency check is performed. The calculation resulted in a Consistency Ratio (CR) of 0.0919, which is less than the 0.1 threshold, thus passing the consistency test.

Therefore, the AHP yields the following weights for the cost components: (1) picking path cost (); (2) storage layout deviation cost (); (3) energy and carbon emission cost (); (4) FIFO penalty cost (); and (5) picker scheduling cost ().

To investigate the impact of different managerial strategies on the solution, this study conducted a trade-off analysis. We designed three realistic managerial scenarios: (1) Balanced Approach, representing the operational model with a comprehensive consideration of all costs as previously described; (2) Cost-Centric Strategy, which prioritizes the control of key expenditures such as storage layout and energy consumption; and (3) Efficiency-Driven Strategy, which designates order fulfillment timeliness as the paramount optimization goal.

For each scenario, we constructed a corresponding AHP judgment matrix and recalculated the weight vector. Subsequently, the proposed PS-GSA algorithm was used for solving.

Table 5 details the final values of each cost component and the changes in the total weighted cost under different weight configurations.

Analysis of the results in

Table 5 reveals that under the “Cost-Centric Strategy,” although the energy cost (

) and layout deviation cost (

) were reduced by 14.4% and 4.4%, respectively, this led to a 32.8% increase in the picking path cost (

). This exposes a phenomenon: to concentrate products in low-energy-consumption zones or ideal storage locations, pickers are compelled to travel longer distances to fulfill orders. Conversely, under the “Efficiency-Driven Strategy,” while the FIFO penalty cost (

) was reduced by 18.3%, the energy cost (

) and layout deviation cost (

) increased by 22.4% and 30.1%, respectively. This shows that to achieve the shortest picking paths, the algorithm stores high-frequency items in locations that are close to the depot but may belong to high-energy-consumption temperature zones, causing an increase in other costs.

To test the robustness of the baseline solution, this study conducted a sensitivity analysis. We employed the one-at-a-time perturbation method, sequentially perturbing the weights of the five cost objectives by

and

. Concurrently, the other weights were proportionally adjusted to ensure their sum remained 1, and the model’s total cost was then recalculated. The analysis results are summarized in

Table 6.

The results in

Table 6 strongly show the robustness of the baseline solution. The fluctuation in each weight cost consistently remained within a minimal range of

. This shows that the model’s optimization results are not sensitive to minor deviations that may exist in the AHP judgments, rendering the decision reliable.

The following is a description of the mathematical model. The model is subject to the following constraints:

- (1)

Storage and Capacity Constraints

The total quantity of a product

i stored across all locations must equal its total demand

. This is expressed as

The quantity of product

i in location

k cannot exceed its capacity. Except for the frozen zone, each location can hold only one product package. A single location cannot be used to store different product types:

Finally, a temperature matching constraint ensures that products are stored only in locations that meet their temperature requirements. If

, then

- (2)

Routing and Scheduling Constraints

The picking path for each order,

, is determined by the coordinates of the locations of its constituent products and must form a tour starting and ending at the depot

. Each order must be assigned to exactly one picker:

- (3)

Product Odor Compatibility Constraint

In fresh product storage allocation, the olfactory properties of different items can significantly affect product quality and the picking environment. Products with strong odors in particular may adversely affect adjacent odor-sensitive or easily contaminated items, leading to quality degradation and a negative customer experience. To address this factor during layout optimization, we introduce a constraint based on product odor compatibility. We assign an odor index

(

) to each product

i, where higher values signify stronger odors and a greater risk of cross-contamination. To prevent contamination, we define a minimum required separation distance

as a function of the odor indices of two products,

i and

j:

The coefficients

and

are empirical values determined through multiple rounds of Delphi method interviews with warehouse management experts. For any pair of products

i and

j (

) whose combined odor indices exceed a predefined threshold

, their assigned storage locations must be separated by at least this minimum distance:

- (4)

Temperature Zone Matching Constraint

To ensure product integrity, it is imperative that each product is assigned only to storage locations that match its specific temperature requirements. For example, ambient products must not be placed in refrigerated or frozen zones. This is enforced by the following constraint. The formulation stipulates that for any product i, the sum of its assignments to all locations k whose temperature zone does not match the product’s required zone must be zero. This effectively forces the decision variable to be zero for any mismatched pair, prohibiting such assignments.

In summary, the mathematical model for the joint optimization of fresh product storage allocation and picking efficiency proposed in this paper is formulated as follows:

Although the weighted sum method is straightforward to implement, it is well known for its potential inability to find solutions in non-convex regions of the Pareto front [

27]. As this problem requires a single, actionable solution and the weights can reflect managerial preferences, the weighted sum approach is deemed appropriate for this context.

3. Solution Methodology

The problem addressed in this study is the integrated Storage Location Assignment and Picker Routing Problem for fresh products, which is a well-established NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem. Its complexity arises from the tight coupling of two interdependent subproblems: the assignment of products to storage locations and the determination of the shortest picking routes for fulfilling customer orders. The latter subproblem is analogous to the computationally intractable Traveling Salesperson Problem (TSP), rendering the overall integrated problem NP-hard. To validate the efficacy of the proposed algorithm, we selected several established algorithms as performance benchmarks: the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), discrete Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and a hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing (GSA) algorithm. These conventional algorithms frequently encounter challenges such as premature convergence to local optima and inadequate convergence rates when applied to high-dimensional, complex problems. To overcome these limitations, we designed a Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing (PS-GSA) algorithm, which achieves a dynamic balance between global exploration and local exploitation [

28].

The proposed PS-GSA differs from conventional hybrids through a deep procedural integration of search philosophies into a unified, discrete framework, rather than a superficial combination of operators. Unlike continuous PSO engines requiring a separate decoding step, PS-GSA’s core is natively discrete, redefining a particle’s “velocity” as a sequence of swaps (SOS)—a list of concrete permutation operations that navigate the solution space directly. This is embedded within a synergistic, ordered pipeline where a global move guided by the SOS-based PSO is intensively refined by a constraint-aware Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS). The resulting solution is then evaluated by the Metropolis acceptance criterion of Simulated Annealing (SA) to probabilistically escape local optima.

To ensure the proposed PS-GSA algorithm exhibits optimal performance, a series of comprehensive sensitivity analyses were conducted on its key parameters. Through computational experiments across multiple test instances, we evaluated the impact of different parameter configurations on both solution quality and convergence efficiency. The parameter values presented in

Table 7 result from this rigorous calibration process, representing the configuration that yields the best performance for the problem context.

To ensure the robustness and optimal performance of the proposed PS-GSA algorithm, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis was conducted on its key parameters that critically influence the search behavior. Through extensive preliminary computational experiments, we systematically evaluated the impact of various parameter combinations on the solution quality and convergence speed. The analysis revealed that the algorithm achieves its best overall performance on the test instances when the crossover probability is set to 0.9, the mutation probability is set to 0.05, the elite retention proportion is configured to 0.25, and the local search probability is determined to be 0.55. For PSO Dynamics, this strategy is designed to foster a dynamic transition from global exploration to local exploitation [

29,

30]. In the early stages, a larger inertia weight

and cognitive factor

encourage diverse searching [

31]. In contrast, the social factor

is intentionally increased over iterations to strengthen social learning, guiding the swarm toward the global optimum in the later stages and promoting convergence.

The core framework of the PS-GSA algorithm is founded on population-based iterative optimization, yet it integrates various optimization mechanisms, including Simulated Annealing and Particle Swarm strategies, at critical junctures.

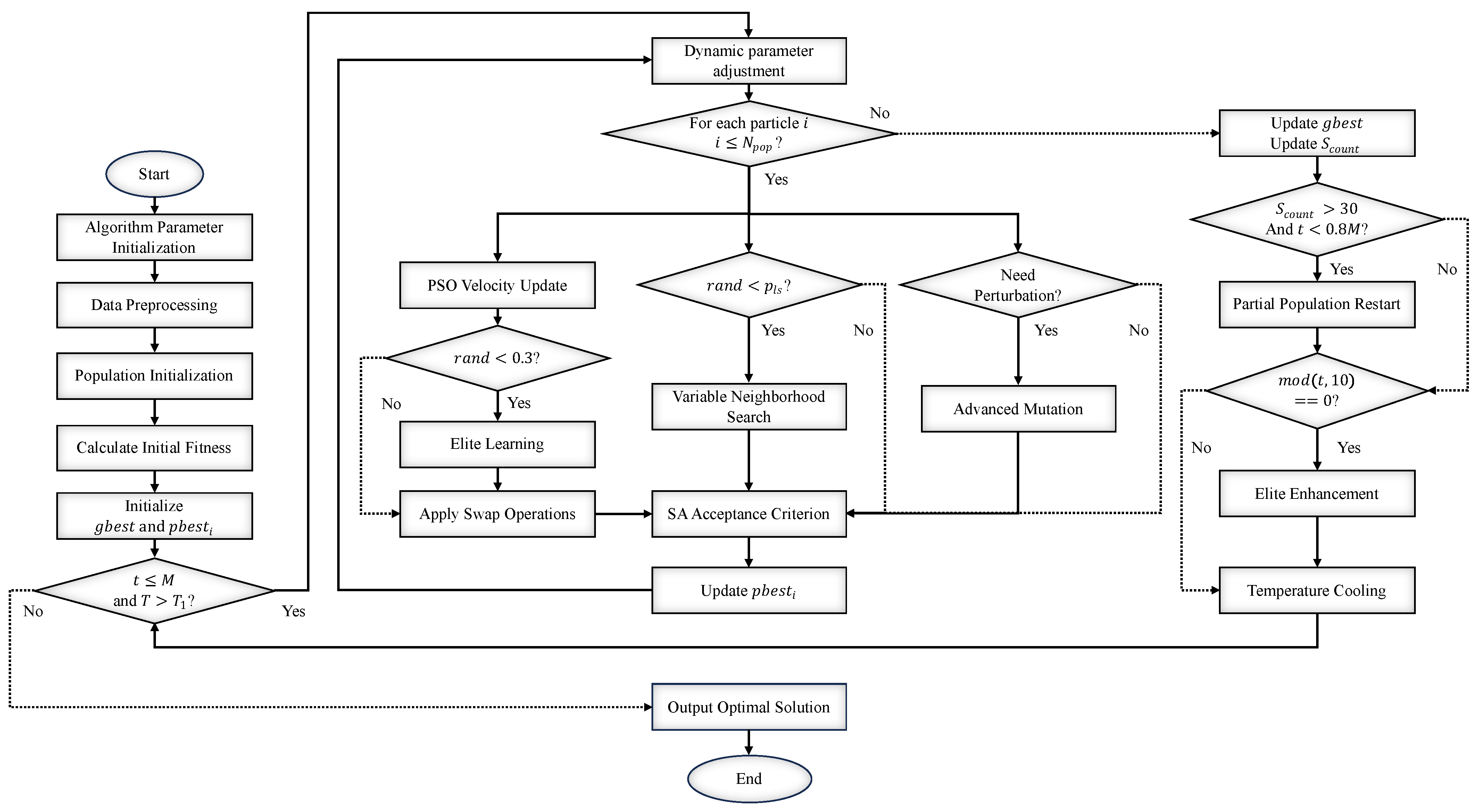

Figure 2 reveals the process of the algorithm.

In order to clearly illustrate the implementation details of the Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic–Simulated Annealing algorithm (PS-GSA) proposed in this study, its detailed algorithmic step-by-step description with pseudo-code is provided below. Unlike traditional meta-heuristic algorithms, PS-GSA organically integrates the global guidance ability of discrete Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), the local mining ability of Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS), and the probabilistic jump-out mechanism of Simulated Annealing (SA).

- Step 1.

Population initialization. A hybrid strategy is used to generate an initial population of size . A total of 20% of the individuals are generated by a greedy heuristic rule to ensure the quality of the initial solution; the remaining 80% of the individuals are generated completely randomly to ensure the diversity of the population.

- Step 2.

Calculation of fitness. Based on the integrated cost objective function constructed in

Section 2, the fitness value of each individual in the population was calculated

.

- Step 3.

Initialize individual and global optima. For each particle i, set its initial position to the individual historical optimal position , and its fitness to the individual optimal fitness . Find the individual with the optimal fitness from the whole population, and record its position and fitness as the global optimal and . Initialize the current temperature of the Simulated Annealing, T, and the stagnation counter, .

- Step 4.

Main loop. When the number of iterations does not reach the maximum number of iterations M, repeat steps 5 through 10.

- Step 5.

Dynamic parameter adjustment. According to the current iteration number

t and the maximum iteration number

M, the inertia weight

, the cognitive factor

, and the social factor

of the PSO are dynamically updated based on Equation (

19).

- Step 6.

Particle Updates. An enhanced particle update process is performed for each particle in the population (see Algorithm 2 for details):

- (1)

Velocity update: Generate a discrete “exchange sequence” of particle velocities by comparing the difference between the current solution and the individual optimal, global optimal, and elite solutions.

- (2)

Position update: Apply the exchange sequence to the current solution to generate a candidate solution .

- (3)

Local enhancement: Perform Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) on the candidate solution with probability to get the enhanced solution .

- (4)

Acceptance decision: Based on the Metropolis acceptance criterion, decide with a certain probability whether to accept the augmented solution as the new position of the particle i or not.

- (5)

Individual optimal update: If the fitness of the new position is better than the individual historical optimal fitness of the particle , then update and .

- Step 7.

Global Optimization Update. After all particles have completed the update, re-evaluate the entire population and if a new global optimum solution is found, update and and zero out the stagnation counter ; otherwise, is added by one.

- Step 8.

Stagnation restarts with elite enhancement. If exceeds the threshold , a partial population restart mechanism is triggered as follows: the top 20% of elite individuals are kept and the bottom 80% are re-initialized randomly to jump out of the local optimum. Meanwhile, every generations (e.g., 10 generations), a deep local search is executed on the current global optimal solution to further extract the optimal solution.

- Step 9.

Temperature attenuation. Attenuation of the temperature T by the cooling factor .

- Step 10.

The algorithm terminates. If , the algorithm terminates and outputs the global optimal solution found and its fitness value ; otherwise, go to step 4.

For ease of reproduction and understanding, we formalize the above steps into pseudo-code. The overall framework of the algorithm is presented in Algorithm 1 and the particle update mechanism is detailed in Algorithm 2.

The input to Algorithm 1 includes objective function

, population size

, maximum number of iterations

M, Simulated Annealing parameters (

), Particle Swarm parameters (

), local search probability

, and stalled restart threshold

. The output comprises the global optimal solution

and its fitness value

.

| Algorithm 1 The overall PS-GSA framework. |

- 1:

//1. Initialization - 2:

- 3:

for to do - 4:

- 5:

▹ Step 3 - 6:

end for - 7:

▹ Step 3 - 8:

- 9:

//2. Main loop - 10:

for to M do ▹ Step 4 - 11:

▹ Step 5 - 12:

for to do - 13:

▹ Step 6 - 14:

end for - 15:

//3. Updating the global optimum with adaptive tuning - 16:

- 17:

if then ▹ Step 7 - 18:

- 19:

- 20:

else - 21:

- 22:

end if - 23:

if and then ▹ Step 8 - 24:

▹ Retain elites, reset most populations - 25:

- 26:

end if - 27:

if then ▹ Step 8 - 28:

- 29:

- 30:

end if - 31:

//4. Temperature decay - 32:

- 33:

end for - 34:

return

|

The input to Algorithm 2 includes current solution (), individual optimal solution , global optimum solution , current temperature T, and local search probability . The output includes updated solutions (), and updated individual optimal solutions .

The above pseudo-code shows the core design ideas of PS-GSA. Algorithm 1 embodies the evolutionary flow of the algorithm, which is notable for the population stagnation judgement and restart mechanism in lines 23–26, and the elite solution depth enhancement mechanism in lines 27–30. These strategies enhance the algorithm’s ability to jump out of the local optimum and are key to the robustness of the algorithm. Algorithm 2 adapts PSO for solving continuous space problems to the permutation optimization problem in this study. The key innovation is to redefine the velocity vector of the traditional PSO as a sequence of swaps, which guides the particles to perform position updates. Ultimately, the acceptance of a new solution is determined by the Metropolis criterion, which not only accepts the better solution unconditionally but also accepts the suboptimal solution with a certain probability, which decreases as the “temperature”

T decreases. This mechanism gives the algorithm the ability to escape from local extremes in the early stage of the search and gradually converge to the optimal solution region in the latter stage, which is the core mechanism to ensure the convergence performance of the algorithm.

| Algorithm 2 Particle Update Process. |

- 1:

//1. Updating Discrete velocity (generation of exchange sequences) - 2:

- 3:

//2. Updating location - 4:

- 5:

//3. Local Search Enhancement - 6:

if

then - 7:

- 8:

else - 9:

- 10:

end if - 11:

- 12:

//4. Metropolis acceptance criteria - 13:

- 14:

if or then - 15:

- 16:

end if - 17:

//5. Updating the individual optimum - 18:

if

then - 19:

- 20:

end if - 21:

return

|

Overall, Algorithms 1 and 2 show the macro-architecture and core execution process of PS-GSA as a whole. In order to further explain the design details and theoretical basis of the key modules, the following subsections will provide a detailed mathematical elaboration of the dynamic parameter control strategy, the neighborhood generation mechanism based on the discrete PSO engine, the Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) used to deepen the local search, as well as the population restarting and elite reinforcement strategies.

(1) Dynamic and Adaptive Parameter Control

To accommodate the varying requirements of the search process at different stages, key parameters within the PS-GSA are dynamically adjusted [

32,

33]. The inertia weight

, cognitive factor

, and social factor

are varied as a function of the iteration count.

Here, and represent the initial and final values of the inertia weight, respectively. This strategy enables the algorithm to favor global exploration in the early stages by employing a larger inertia weight and cognitive factor , while shifting focus toward convergence on the global optimum in later stages with a smaller inertia weight and a larger social factor .

(2) Neighborhood Generation via Discrete Particle Swarm Optimization

The primary driver of the PS-GSA is a discrete PSO engine specifically adapted for permutation-based problems [

34]. In this framework, a particle’s “velocity,”

, is defined not as a continuous vector but as a sequence of swaps (SOS). The velocity update mechanism integrates four components: inertia, personal cognitive influence, social learning, and elite-guided learning [

35,

36]:

where

is the personal best position found by particle i, and is the global best position found by the entire population.

is a superior individual selected randomly from an elite subset of the population.

The ⊖ operator compares two permutations and generates a minimal sequence of swaps required to transform one into the other.

The ⊗ operator denotes a probabilistic sampling of a swap sequence, thereby controlling the influence of each term.

The ⊕ operator represents the application of the final swap sequence (the velocity) to a particle’s current position, thereby generating a new candidate solution.

is the elite learning rate.

A new velocity vector

is generated and then applied to the current position

to produce a candidate solution

:

To operationalize the PSO framework for this permutation-based problem, the concepts of “velocity” and “position update” are redefined in a discrete context. A particle’s velocity, , is not a continuous vector but is represented as a sequence of swaps (SOS)—an ordered list of index pairs, where each pair signifies a swap operation to be performed on the chromosome (the solution permutation).

The generation of this SOS, represented abstractly by the ⊖ operator in Equation (

21), is a critical step. For instance, to compute the cognitive component (

), the algorithm compares the current solution

with the particle’s personal best solution

. It identifies all indices where the two permutations differ and then constructs a sequence of workable swaps that moves

closer to

. A key innovation here is the constraint-aware nature of this process: a swap between two indices is only considered valid if it preserves the feasibility of the solution, specifically by ensuring that both affected products remain in their required temperature zones after the exchange. It is important to note that this process generates a feasible sequence of swaps, not necessarily the minimal one.

The final velocity vector,

, is composed by probabilistically selecting and concatenating swap sequences generated from the inertia, cognitive, social, and elite-learning components. The application of this velocity to update the particle’s position, denoted by the ⊕ operator in Equation (

22), is then performed. This operation involves the sequential and deterministic application of every swap pair in the final SOS to the current chromosome

. The stochastic nature of the particle’s movement arises from the composition of its velocity vector, not from the application of it.

To further clarify this process, let us consider a small example involving five products (P1–P5), six available locations (L1–L6), and three temperature zones (1: Ambient, 2: Refrigerated, 3: Frozen). The setup is detailed in

Table 8.

The table supposes the current solution for a particle is , while its personal best is . It is important to recognize that both of these are feasible solutions, as every product is assigned to a location that satisfies its temperature requirement. To generate the cognitive component of velocity, the algorithm performs a randomized search for feasible exchanges among the differing positions. This approach is a deliberate design choice to maintain the explorative nature of PSO and mitigate the risk of premature convergence.

The next few steps show how the PSO operators are translated into a concrete search mechanism:

Step 1: Identify Differences. By comparing and , we find differences at indices 1, 2, 3, and 4. Product is correctly assigned to in both solutions.

Step 2: Generate Cognitive Swaps. The algorithm now performs a randomized search for feasible swaps among the differing indices.

Attempt 1 (Successful): Consider a swap between index 1 () and index 2 (). requires Zone 1 and is currently in (Zone 1). requires Zone 1 and is currently in (Zone 1). If they swap, will be in (Zone 1) and will be in (Zone 1). Since both locations satisfy the requirements of the new products, the swap (1, 2) is valid and is added to the potential SOS.

Attempt 2 (Successful): Similarly, a swap between index 3 (P3) and index 4 () is considered. is in (Zone 2), and is in (Zone 2). Swapping them is also valid. The swap (3, 4) is added to the potential SOS.

Attempt 3 (Failure): Suppose we attempt an invalid swap between index 1 () and index 3 (). requires Zone 1, but its proposed new location is in Zone 2. This violates the temperature constraint. Therefore, the swap (1, 3) is invalid and is discarded.

Step 3: Form the SOS. Based on the successful searches, the generated sequence of swaps for the cognitive component is .

Step 4: Update Position. The velocity is formed in this simplified case, so let us assume it is just SOS. The update operation is performed by sequentially applying the swaps:

Initial:

Apply swap (1, 2):

Apply swap (3, 4):

Final:

(3) Local Search Enhancement via Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS)

To improve the local optimality of the candidate solution [

37,

38], a Variable Neighborhood Search (VNS) is applied to

with probability

. VNS facilitates an in-depth exploration by systematically alternating among a predefined set of neighborhood structures, for

. This process can be formalized as follows:

The resulting solution, , which has been enhanced by VNS, proceeds to the Simulated Annealing acceptance phase.

(4) Acceptance Criteria based on Simulated Annealing (SA)

Instead of the deterministic update rule typical of PSO, PS-GSA incorporates the Metropolis acceptance criterion from Simulated Annealing to probabilistically determine the acceptance of the new solution

. Given the change in the objective function value,

, the acceptance probability P is defined as

Here, is the system “temperature” at iteration t, which follows a geometric cooling schedule , with being the cooling rate. This mechanism endows the algorithm with the ability to escape from local optima.

To counteract premature population convergence observed in standard genetic algorithms, two specific mechanisms are integrated into the PS-GSA.

The first is a multi-operator mutation strategy. Throughout the iterative process, the algorithm probabilistically applies a mutation operator, randomly selected from a predefined library , to individuals, enhancing the diversity of perturbations within the population.

The second is a partial population restart mechanism [

39]. The algorithm monitors the improvement of the global best solution using a stagnation counter,

. A restart is triggered if

surpasses a predefined threshold,

. This mechanism preserves the top

(e.g., 20% of the population) as elites and replaces the remaining

individuals with new, randomly generated solutions, rapidly reinvigorating the population.

Finally, to meticulously refine the current best solution, the algorithm executes a computationally intensive and more thorough local search on the global best solution, , at a fixed frequency of iterations. This procedure is designed to systematically explore the neighborhood of to identify solutions of superior quality.

4. Computational Results and Analysis

This chapter presents an evaluation of the proposed Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing (PS-GSA) algorithm. To validate its effectiveness and robustness, a series of computational experiments were conducted on multiple problem instances of increasing scale. The performance of PS-GSA is systematically compared against four established benchmark algorithms: Genetic Algorithm (GA), Simulated Annealing (SA), a Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (HPSO), and a baseline hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing (GSA) algorithm. The analysis encompasses solution quality, statistical significance and algorithmic convergence. All algorithms were implemented in MATLAB R2022a and executed on a laptop computer equipped with a 12th Gen Intel Core i7-12700H CPU, 16 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050Ti Laptop GPU.

The original data for this experiment comes from YouDaji (Wuhan) Supply Chain Co. (Wuhan, China). The company focuses on meeting the market demand of the whole fresh food industry chain, constantly broadening its service areas, and devotes itself to providing commodity trading, fresh food collection, specialized warehousing and logistics, circulation processing and other services for the participants of the whole fresh food industry chain, and has completed its strategic layouts in Wuhan, Xiangyang, Shenzhen, Yichang, and Ningbo in various regions successively. The company is committed to building a “S2B2B” agricultural trading platform, and its fresh produce warehousing and sorting process is centered on the core system of “preserving freshness and improving efficiency”.

To assess the performance and scalability of the algorithms when faced with increasing problem complexity, the instances are scaled by the number of products , with . The benchmark algorithms selected for comparison are GA, SA, HPSO, and GSA. The justification for each is

Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Simulated Annealing (SA): These are foundational metaheuristics for combinatorial optimization. They are included to establish a performance baseline against classic methods.

Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization (HPSO): This algorithm is included as a representative of advanced, contemporary PSO-based methods. Given that PSO is a core component of the proposed algorithm, comparing against a PSO variant is essential for a fair evaluation.

Genetic-Simulated Annealing (GSA): This hybrid serves as a crucial ablation baseline. By comparing PS-GSA to GSA, the specific performance contribution of the high-level Particle Swarm Optimization guidance mechanism can be isolated and quantified, showing the value added by the novel hierarchical structure of the proposed algorithm.

To provide a holistic assessment, performing each algorithm was evaluated based on multiple metrics derived from 30 independent runs for each algorithm-instance combination.

Table 9 summarizes the overall performance of the five algorithms. For each problem size (

N), the table reports the mean and standard deviation of the final objective function values, the best solution found across 30 runs, and the average runtime in seconds. The best-performing value for each metric (excluding runtime) is highlighted in bold.

The results presented in

Table 9 clearly show the superior performance of the proposed PS-GSA algorithm in terms of solution quality. Across all five problem instances, from

to

, PS-GSA consistently achieves the lowest (best) mean objective function value. For instance, in the largest and most complex case (

), PS-GSA obtains a mean fitness of 8708.58, which represents a 4.08 % improvement over the next-best algorithm, SA (9078.99), and a 6.02 % improvement over HPSO (9267.09). This trend holds for the best-found solutions as well, where PS-GSA identifies solutions of significantly higher quality than any of the benchmark algorithms. The data shows that as the problem size and complexity increase, the performance gap between PS-GSA and the other algorithms widens.

To formally confirm these results,

Table 10 presents the results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, which compares the 30 independent run results of PS-GSA against each benchmark algorithm for every instance. The table displays the calculated

p-value and the percentage improvement of PS-GSA’s mean fitness over comparison algorithms.

The statistical analysis provides evidence for the superiority of PS-GSA. For all problem instances with , the p-values for the comparison of PS-GSA against all four benchmark algorithms are substantially lower than the 0.05 significance level. This shows that the observed performance advantage of PS-GSA is statistically significant and not a result of random chance. However, an important nuance is observed in the smallest instance (). While PS-GSA still outperforms GA in mean fitness, the difference is not statistically significant (). This outcome is not a weakness but an insight into the algorithm’s domain of applicability. The search space for the problem is relatively small and less complex. In such a landscape, the sophisticated global guidance and local search mechanisms of PS-GSA provide diminishing returns, as a simpler heuristic like GA can explore the space adequately.

The convergence and stability of the algorithm will be analyzed below.

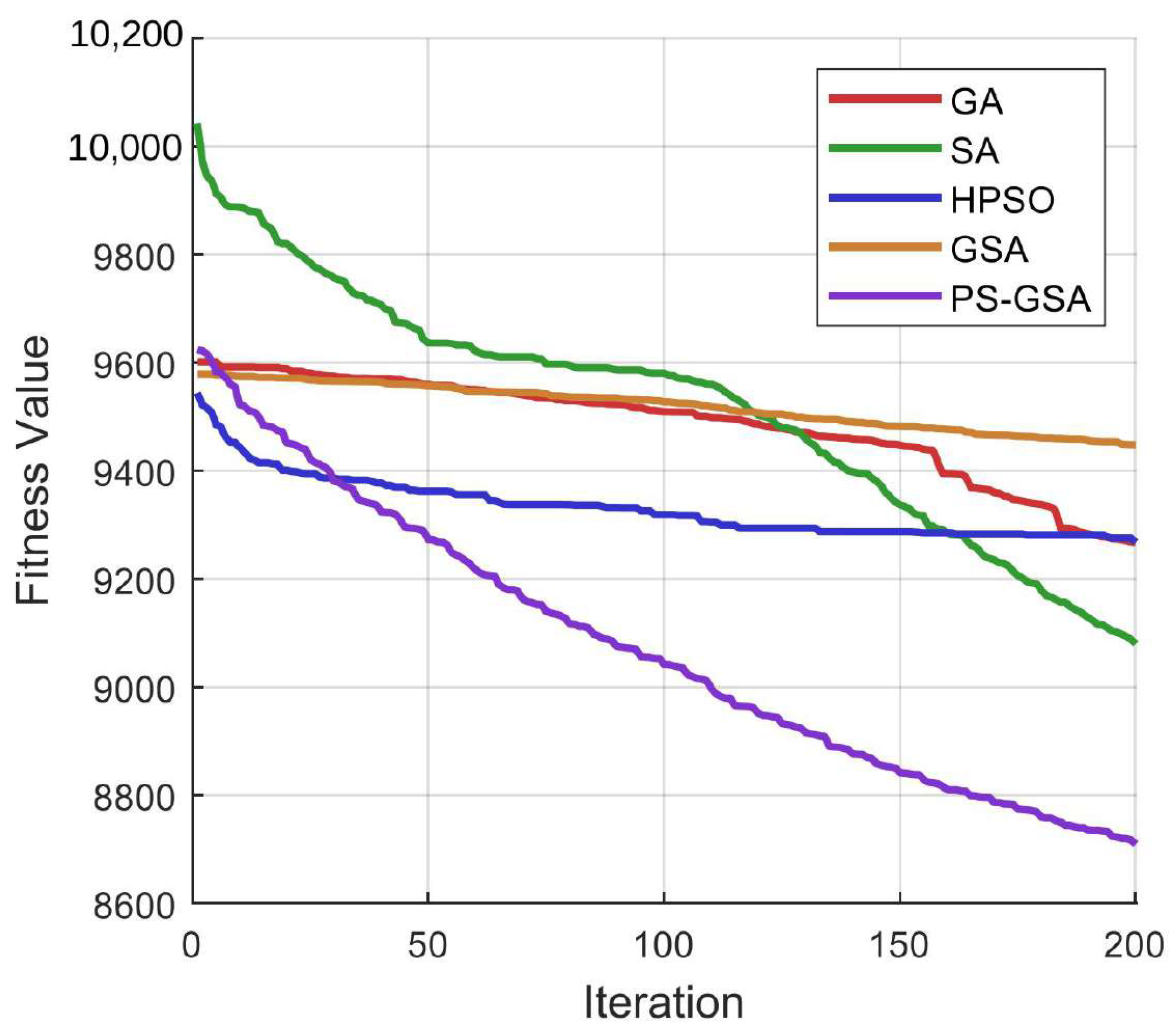

Figure 3 illustrates the average convergence performance of the five algorithms over 200 iterations for the largest instance (

). The y-axis represents the average fitness value, while the x-axis represents the iteration number.

The convergence curves of the algorithms in

Figure 3 precisely represent the different convergence performances. The curves of GA and GSA do not show any significant degradation until 150 iterations; the curves of SA and HPSO show rapid performance improvement within the first 50 iterations, but then the curves flatten out to form an obvious plateau period. In contrast, the convergence curve for PS-GSA shows a sustained and steady decline throughout the entire 200-iteration run. It does not have hard plateaus or erratic swings, suggesting that it continues to explore the solution space and identify improvements even in the later stages of the search.

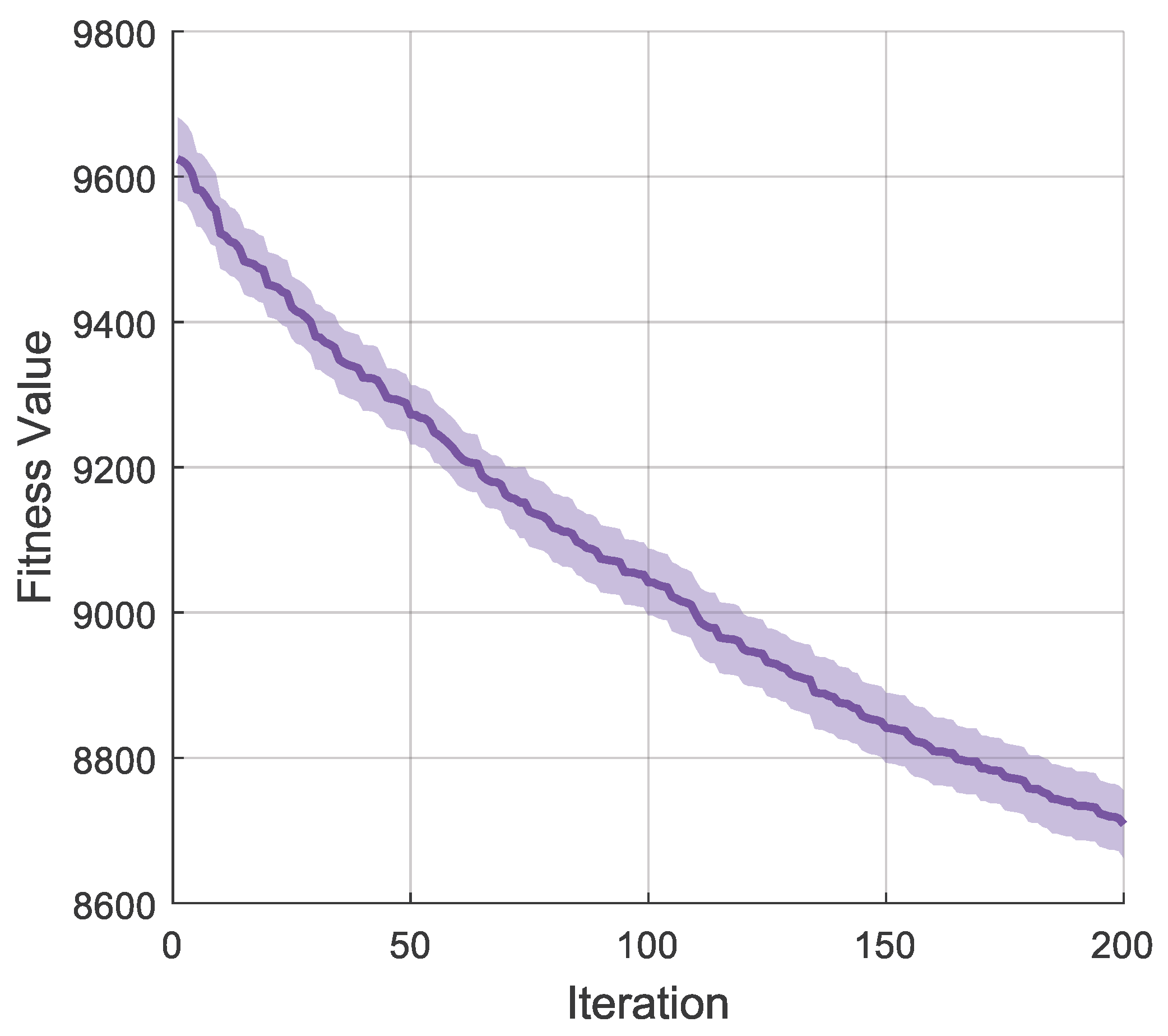

Figure 4 further reinforces this by showing the tight 95% confidence interval around the PS-GSA mean convergence curve, showing low variance and consistent performance across runs.

The convergence curve for PS-GSA exhibits a slight downward trend at the end of 200 iterations, indicating that marginal improvements could be possible with an extended run. However, the rate of convergence has slowed significantly, suggesting the algorithm is approaching the optimal solution region. Therefore, the 200-iteration limit is established as a reasonable trade-off between solution quality and computational cost.

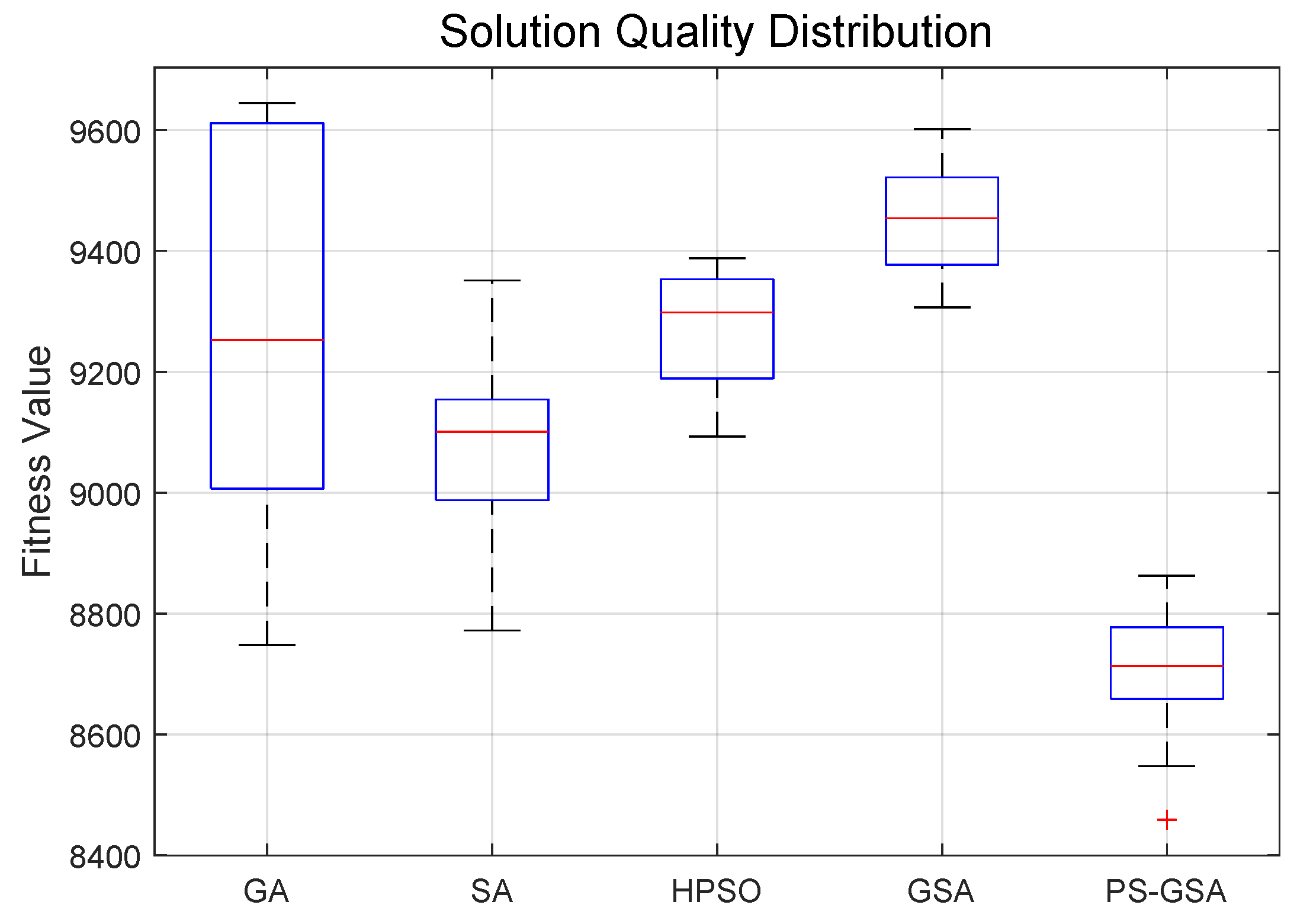

Beyond average performance, the consistency of an algorithm is critical for its practical application.

Figure 5 presents box plots illustrating the distribution of the final solutions obtained from the 30 independent runs for each algorithm on the

instance.

Figure 5 provides a clear visual summary of both the solution quality and stability of the algorithms. The PS-GSA box plot is positioned lowest on the y-axis, confirming that it achieves the best median fitness value. More importantly, the interquartile range, represented by the height of the box, is notably compact for PS-GSA. This shows that the middle 50% of its solutions are tightly clustered around the median. In contrast, the box plots for GA and SA are much taller and have longer whiskers, signifying a high variability in their outcomes. This high variance makes them less reliable, as a single run could yield either a good or a poor result. The performance of PS-GSA is evidenced by its low standard deviation (

Table 9) and tight interquartile range. The global guidance from the PSO framework reduces the likelihood of the search deviating into poor regions of the solution space, while the VNS and SA components ensure thorough exploitation of promising areas.

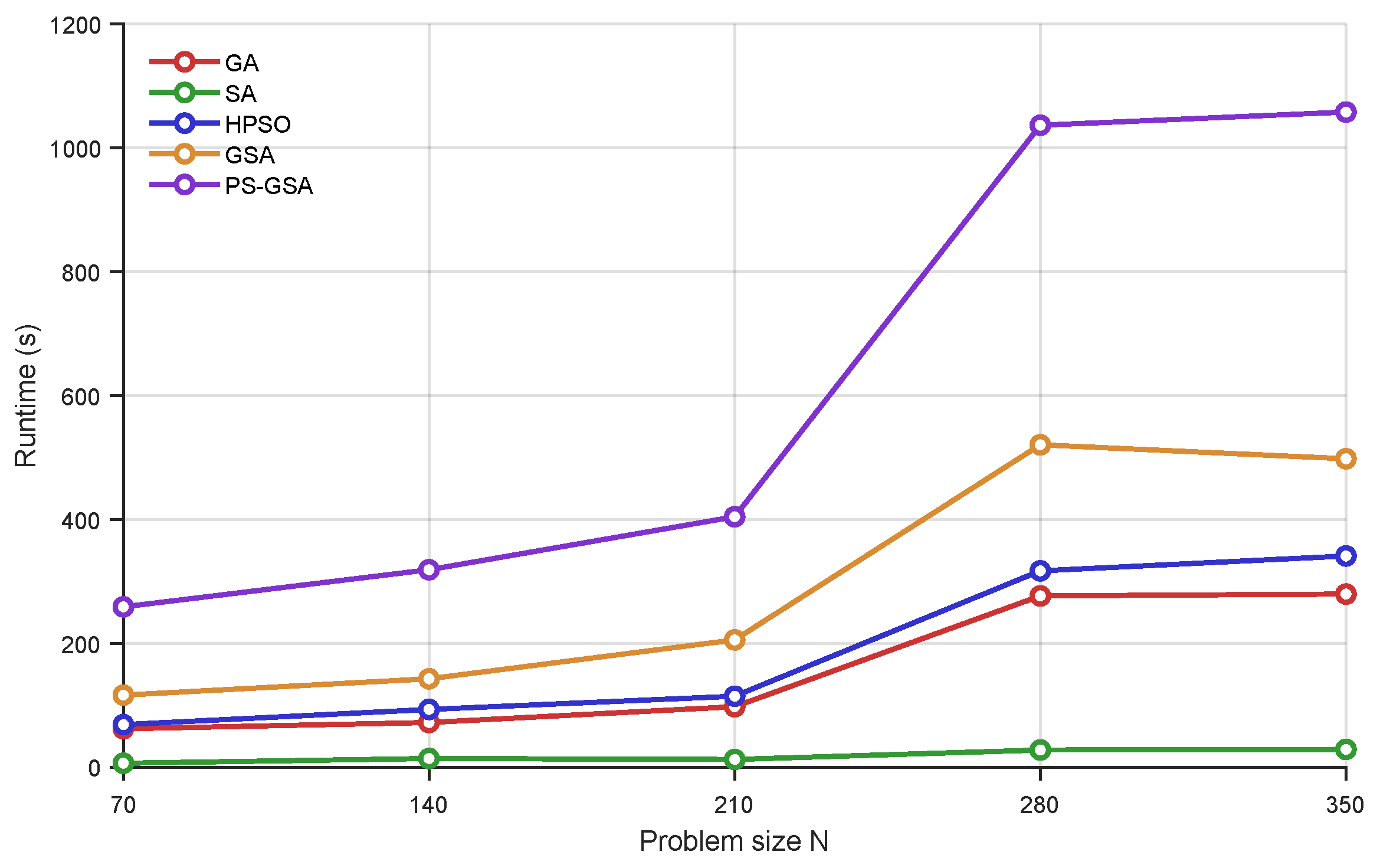

While solution quality and stability are paramount, computational efficiency is also a key consideration.

Figure 6 plots the average computational time of each algorithm as a function of problem size. The data sourced from

Table 9 demonstrates how the computational demands of each algorithm scale with increasing complexity.

The analysis of computational time reveals that the proposed PS-GSA is the most computationally intensive algorithm among the tested set. As shown in

Figure 6, its runtime increases substantially with problem size, reaching approximately 1058 s for the largest instance (

). In contrast, SA is the fastest, requiring only approximately 29 s for the same instance. However, this higher runtime should be interpreted not as a weakness but as a justified trade-off for achieving superior solution quality. This higher computational cost is an inherent and expected consequence of PS-GSA’s architectural complexity. The additional time is consumed by the sophisticated operators that simpler algorithms lack: calculating the discrete PSO swap sequences, performing the systematic VNS local searches, and executing the iterative logic of the SA acceptance criterion.

Finally, to provide a tangible illustration of the algorithm’s output, this section presents a sample of the optimized storage location assignment for the largest instance (

).

Table 11 shows the initial and final storage coordinates for a selection of products, translating the abstract fitness value into a concrete physical layout.

The sample assignments in

Table 11 illustrate that PS-GSA successfully reassigns products to new locations within the warehouse grid. A key observation is that all assignments adhere to the fundamental constraints of the model. For instance, Product 52, which requires a refrigerated environment (Area 2), is moved from one location to another but remains within the designated refrigerated zone. The same holds for ambient and refrigerated products.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to solve the problem of joint optimization of storage allocation and order picking for fresh products. To address this challenge, this paper constructs a comprehensive mathematical model that integrates five major costs—picking paths, slotting layout, energy consumption, First-In-First-Out principles, and personnel scheduling—and proposes an innovative Particle Swarm-guided hybrid Genetic-Simulated Annealing (PS-GSA) algorithm. The core contribution of this algorithm lies in its hierarchical and synergistic optimization framework: a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm acts as a global strategy guide, directing the population evolution of a lower-level Genetic Algorithm (GA), while deeply integrating the local search capabilities of Variable Neighborhood Search with the probabilistic escaping mechanism of Simulated Annealing (SA). Computational experiments based on real enterprise data have showed the superior performance of the proposed PS-GSA algorithm. In comparisons with benchmark algorithms including standard GA, SA, HPSO, and GSA, PS-GSA shows significant and statistically robust advantages in solution quality, convergence efficiency, and stability, with performance improvements ranging from 4.08% to 9.43% over the next-best algorithm, especially in large-scale instances.

This study provides significant theoretical and methodological implications for the field of combinatorial optimization. First, the “master–slave” hierarchical architecture adopted by PS-GSA, which uses the global exploration capabilities of PSO to guide the evolutionary direction of the GA population, provides the momentum for a sustained and effective search in complex solution spaces. This transcends the simple concatenation of operators found in conventional hybrid algorithms, forming a deeper synergistic mechanism. Second, by employing the Metropolis acceptance criterion of SA as a probabilistic decision gate and embedding VNS to enhance local search, this study constructs a sophisticated dynamic balancing mechanism that effectively coordinates the algorithm’s behavior between global exploration and local exploitation. The success of this theoretical design is visually validated by the algorithm’s convergence curve: unlike algorithms such as SA and HPSO, which enter a “plateau period” after rapid initial improvements, PS-GSA’s convergence curve exhibits a sustained and steady decline, showing its ability to effectively avoid search stagnation and continuously discover better solutions in complex solution spaces.

In terms of managerial practice, this study provides a powerful and flexible decision-support tool that can deliver tangible operational value to warehouse managers in the fresh e-commerce sector. The comprehensive cost model not only covers the key factors affecting the efficiency and cost of fresh product storage allocation but, more importantly, empowers managers to customize optimization objectives based on different strategic priorities (e.g., cost control, order timeliness, and energy conservation) by incorporating the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for weight configuration. The results of the trade-off analysis clearly quantify the pros and cons of different management strategies. For instance, a “cost-centric strategy” can significantly reduce energy costs by 14.4% but at the expense of a 32.8% increase in picking path costs. Conversely, an “efficiency-driven strategy” improves FIFO execution efficiency at the cost of higher energy and layout expenses. These quantitative results enable managers to shift from reactive daily operations to proactive, data-driven strategic planning.

Despite the significant achievements of this study, several limitations remain, which also open up new directions for future research. First, the validity of this research was verified using specific warehouse layout and operational data from a single enterprise; the generalizability of its conclusions to warehouses with different layouts (e.g., fishbone), scales, or demand patterns needs further examination. Second, some assumptions in the model, such as treating picker travel speed as a constant, simplify real-world situations. Future research could introduce dynamic and stochastic factors, such as picker fatigue or demand uncertainty, to build more dynamic optimization models. Third, while the PS-GSA algorithm delivers high-quality solutions, its higher computational time represents a performance trade-off. Future work could explore the use of parallel computing to reduce solution time or develop machine learning-based surrogate models to meet real-time decision-making needs. Finally, although the weighted-sum method used in this study effectively reflects decision-maker preferences, it has inherent limitations in handling non-convex Pareto fronts.