Qualitative Analysis of Delay Stochastic Systems with Generalized Memory Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We present a novel analysis of FDSDEs, establishing, for the first time, the existence of unique solutions that depend continuously on initial conditions and the fractional derivative order, alongside the Av-Pr for the HKFD in the th moment sense.

- Our findings are broadly applicable due to the HKFD’s generality, which incorporates many specific fractional derivatives as special cases.

- A key advancement of our work is the generalization of standard well-posedness and regularity results from the conventional setting to the more comprehensive space.

2. Preliminaries

- . There are and , such as

- and are essential-bounded, so

- , ; there exists a , ensuring that

- ,,,, ; there is , satisfying the following:

- For , , and , we have

3. Generalized Results

3.1. Well-Posedness

3.2. Regularity

4. Averaging Principle

5. Applications

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gündoǧdu, H.; Joshi, H. Numerical analysis of time-fractional cancer models with different types of net killing rate. Mathematics 2025, 13, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, M.I.; Etemad, S.; Rezapour, S. A novel analytical Aboodh residual power series method for solving linear and nonlinear time-fractional partial differential equations with variable coefficients. AIMS Math. 2022, 7, 16917–16948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, B.K.; Joshi, H.; Dave, D.D. Portraying the effect of calcium-binding proteins on cytosolic calcium concentration distribution fractionally in nerve cells. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2018, 10, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, M.I.; Akgül, A. A novel approach for solving linear and nonlinear time-fractional Schrödinger equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 162, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, M.I.; Akgül, A.; Bayram, M. Series and closed form solution of Caputo time-fractional wave and heat problems with the variable coefficients by a novel approach. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, E.M.; Harikrishnan, S.; Kanagarajan, K. On the existence and stability of boundary value problem for differential equation with Hilfer-Katugampola fractional derivative. Acta Math. Sci. 2019, 39, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Kumam, P.; Jarad, F.; Borisut, P.; Sitthithakerngkiet, K.; Ibrahim, A. Stability analysis for boundary value problems with generalized nonlocal condition via Hilfer–Katugampola fractional derivative. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhairat, S.P.; Samei, M.E. Nonexistence of global solutions for a Hilfer-Katugampola fractional differential problem. Partial Differ. Equ. Appl. Math. 2023, 7, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.U.; Khan, M.A.; Chu, Y.M. A new generalized Hilfer-type fractional derivative with applications to space-time diffusion equation. Results Phys. 2021, 22, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.S.; Oliveira, D.S.; Rodrigues, F.G.; de Oliveira, E.C. The fractional space-time radial diffusion equation in terms of the Fox’s H-function. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2019, 515, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, S.; Jahromi, A.F.; Heydari, M.H. A cardinal-based numerical method for fractional optimal control problems with Caputo-Katugampola fractional derivative in a large domain. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 55, 1719–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mshary, N.; Ahmed, H.M.; Ghanem, A.S.; Ahmed, A.S. Hilfer-Katugampola fractional stochastic differential inclusions with Clarke sub-differential. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambo, Y.Y.; Jarad, F.; Baleanu, D.; Abdeljawad, T. On Caputo modification of the Hadamard fractional derivatives. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2014, 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.S.; Capelas de Oliveira, E. On a Caputo-type fractional derivative. Adv. Pure Appl. Math. 2019, 10, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, M.D.; Tatar, N.E. Well-Posedness and Stability for a Differential Problem with Hilfer-Hadamard Fractional Derivative. In Abstract and Applied Analysis; Hindawi Publishing Corporation: London, UK, 2013; Volume 2013, p. 605029. [Google Scholar]

- Katugampola, U.N. New approach to a generalized fractional integral. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilfer, R. Fractional time evolution. In Applications of Fractional Calculus in Physics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2000; pp. 87–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbas, A.A.; Srivastava, H.M.; Trujillo, J.J. Theory and Applications of Fractional Differential Equations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 204. [Google Scholar]

- Hilfer, R. Threefold introduction to fractional derivatives. In Anomalous Transport: Foundations and Applications; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; pp. 17–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kahouli, O.; Albadran, S.; Elleuch, Z.; Bouteraa, Y.; Makhlouf, A.B. Stability results for neutral fractional stochastic differential equations. AIMS Math 2024, 9, 3253–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hayat, K.; Zahir, A.; Shah, K.; Abdeljawad, T. Qualitative analysis of fractional stochastic differential equations with variable order fractional derivative. Qual. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2024, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, A.; Alamrani, F.M.; Akhtar, J.; Alatawi, A.; Alshaban, E.; Khatoon, A.; Khan, F.A. Study on Controllability for Ψ-Hilfer Fractional Stochastic Differential Equations. Fractal Fract. 2024, 8, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, K.; Ravikumar, K.; Varshini, S. Fractional neutral stochastic differential equations with Caputo fractional derivative: Fractional Brownian motion, Poisson jumps, and optimal control. Stoch. Anal. Appl. 2021, 39, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Djaouti, A.; Imran Liaqat, M. Qualitative analysis for the solutions of fractional stochastic differential equations. Axioms 2024, 13, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Abebe, M.A.; Nazir, T. Strong Convergence of Euler-Type Methods for Nonlinear Fractional Stochastic Differential Equations without Singular Kernel. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, M.; Vadivoo, B.S. Analysis of controllability in Caputo–Hadamard stochastic fractional differential equations with fractional Brownian motion. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moualkia, S.; Xu, Y. On the existence and uniqueness of solutions for multidimensional fractional stochastic differential equations with variable order. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, C.; Khan, M.A.; Atangana, A.; Kumar, S. A new financial chaotic model in Atangana-Baleanu stochastic fractional differential equations. Alex. Eng. J. 2021, 60, 5193–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouagwa, M.; Cheng, F.; Li, J. Impulsive stochastic fractional differential equations driven by fractional Brownian motion. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 2020, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzade, J.A.; Mahmudov, N.I. Finite time stability analysis for fractional stochastic neutral delay differential equations. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2024, 70, 5293–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Ni, J. New Lyapunov-type inequalities for fractional multi-point boundary value problems involving Hilfer-Katugampola fractional derivative. AIMS Math 2022, 7, 1074–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.S.; Huong, P.T.; Kloeden, P.E.; Vu, A.M. Euler-Maruyama scheme for Caputo stochastic fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2020, 380, 112989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

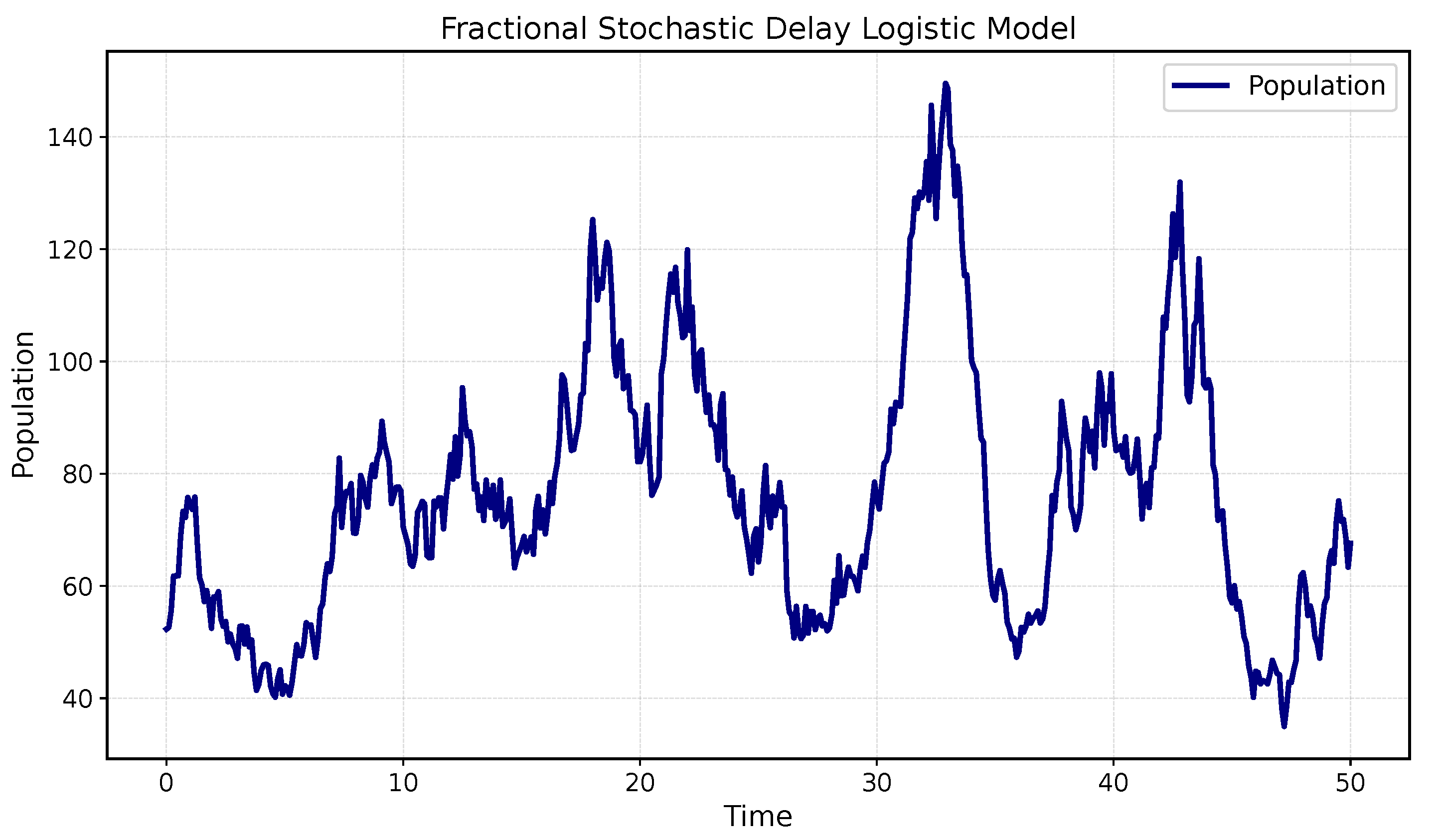

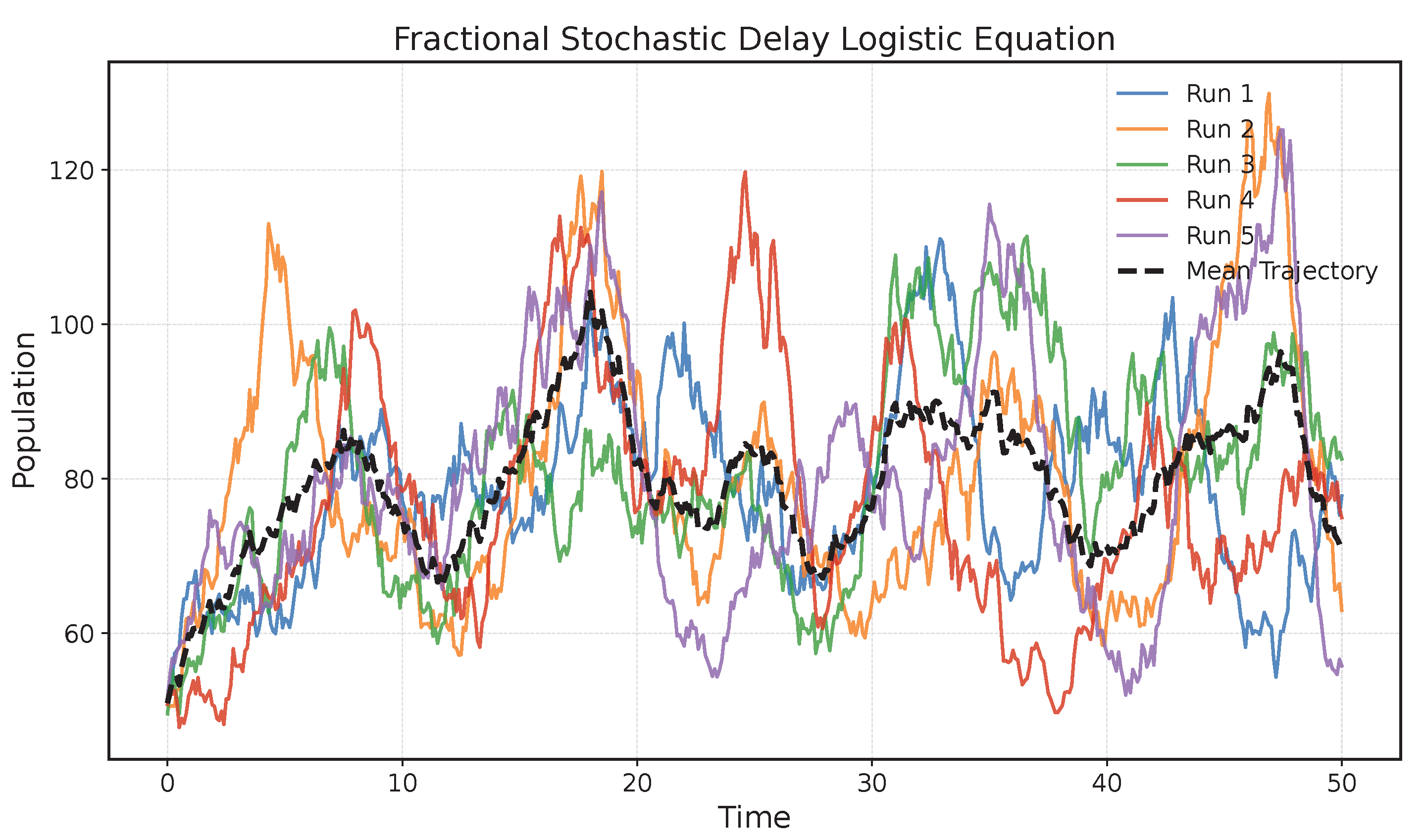

| Symbol | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Fractional order | , | |

| r | Growth rate | |

| K | Carrying capacity | 100 |

| Time delay | ||

| h | Harvesting rate | |

| Noise intensity | ||

| Simulation time | 50 | |

| Time step | ||

| Initial condition |

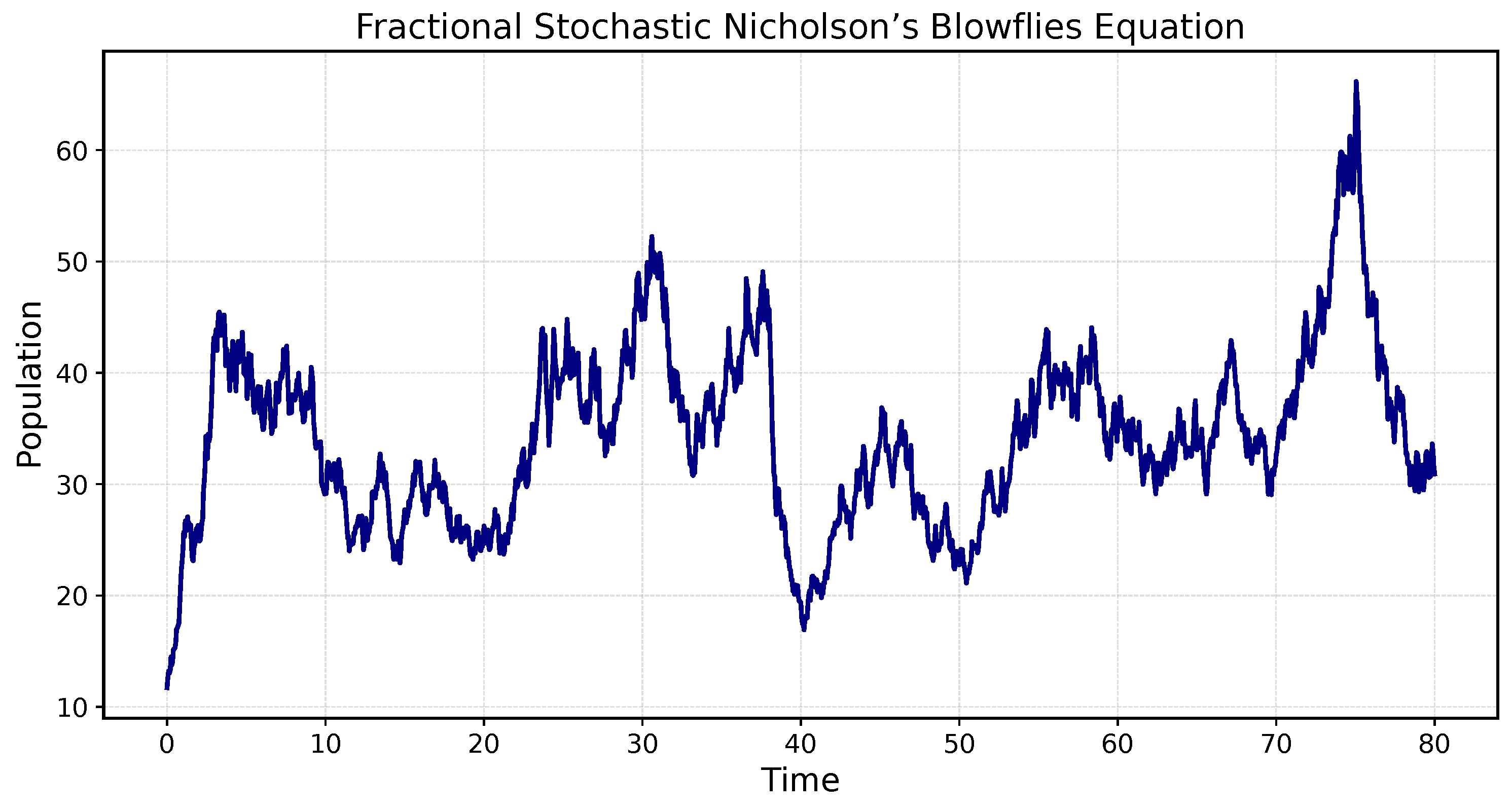

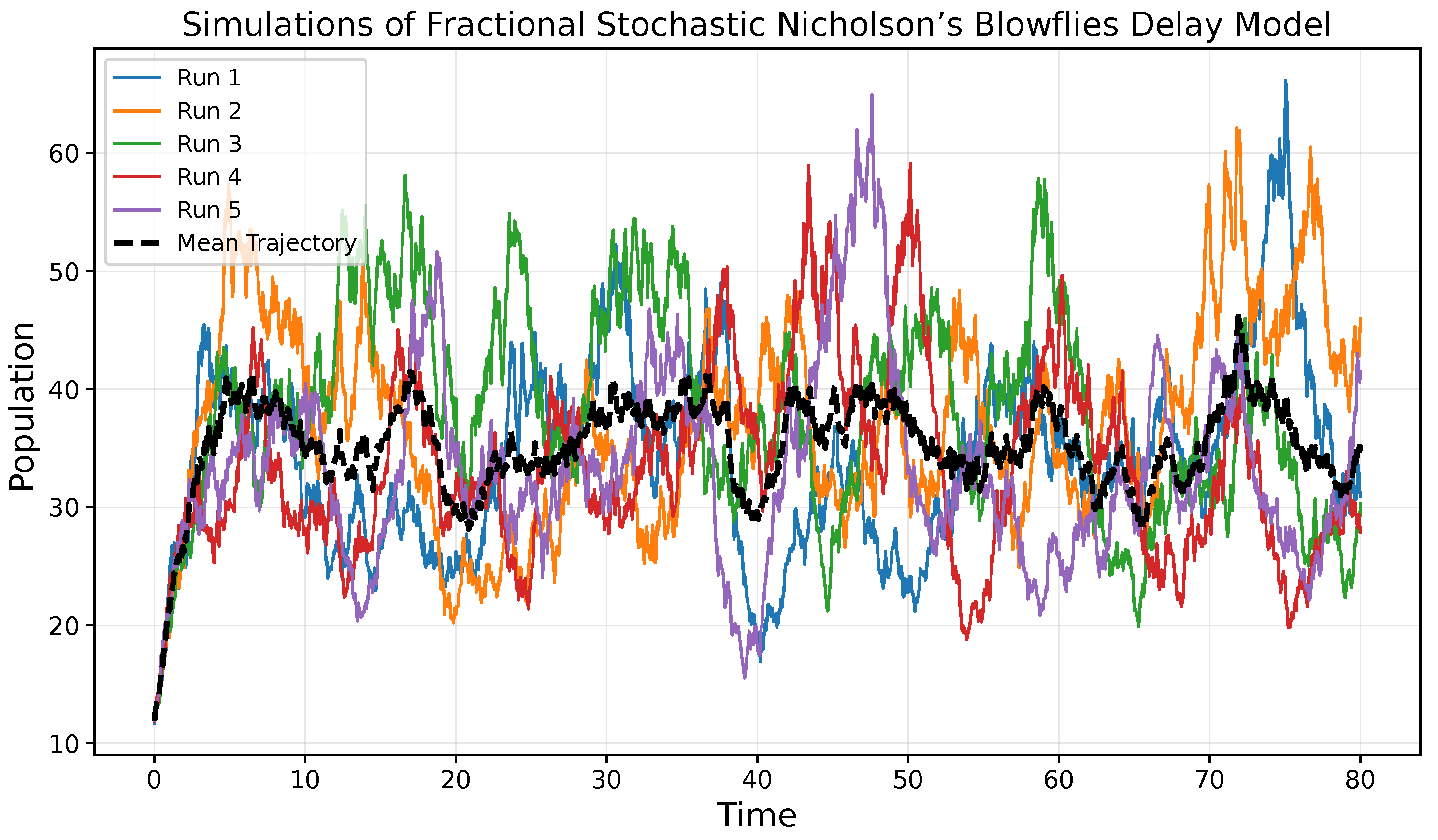

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Fractional order | 0.9 | |

| Death rate | 0.1 | |

| Reproduction coefficient | p | 3.0 |

| Density effect coefficient | a | 0.1 |

| Time delay | 2.0 | |

| Noise intensity | 0.15 | |

| Total simulation time | 80.0 | |

| Time step size | 0.05 | |

| Initial history function | , |

| Time | Original | Averaged | Absolute Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.000000 | 1.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 1 | 1.023456 | 1.021789 | 0.001667 |

| 2 | 1.045678 | 1.043210 | 0.002468 |

| 3 | 1.067890 | 1.064321 | 0.003569 |

| 4 | 1.089012 | 1.085432 | 0.003580 |

| 5 | 1.110234 | 1.106543 | 0.003691 |

| 6 | 1.131456 | 1.127654 | 0.003802 |

| 7 | 1.152678 | 1.148765 | 0.003913 |

| 8 | 1.173890 | 1.169876 | 0.004014 |

| 9 | 1.195012 | 1.190987 | 0.004025 |

| 10 | 1.216234 | 1.212098 | 0.004136 |

| 11 | 1.237456 | 1.233209 | 0.004247 |

| 12 | 1.258678 | 1.254320 | 0.004358 |

| 13 | 1.279890 | 1.275431 | 0.004459 |

| 14 | 1.301012 | 1.296542 | 0.004470 |

| 15 | 1.322234 | 1.317653 | 0.004581 |

| 16 | 1.343456 | 1.338764 | 0.004692 |

| 17 | 1.364678 | 1.359875 | 0.004803 |

| 18 | 1.385890 | 1.380986 | 0.004904 |

| 19 | 1.407012 | 1.402097 | 0.004915 |

| 20 | 1.428234 | 1.423208 | 0.005026 |

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error | 0.003876 |

| Maximum Absolute Error | 0.005026 |

| Minimum Absolute Error | 0.000000 |

| Root Mean Square Error | 0.003941 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Djaouti, A.M.; Liaqat, M.I. Qualitative Analysis of Delay Stochastic Systems with Generalized Memory Effects. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213409

Djaouti AM, Liaqat MI. Qualitative Analysis of Delay Stochastic Systems with Generalized Memory Effects. Mathematics. 2025; 13(21):3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213409

Chicago/Turabian StyleDjaouti, Abdelhamid Mohammed, and Muhammad Imran Liaqat. 2025. "Qualitative Analysis of Delay Stochastic Systems with Generalized Memory Effects" Mathematics 13, no. 21: 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213409

APA StyleDjaouti, A. M., & Liaqat, M. I. (2025). Qualitative Analysis of Delay Stochastic Systems with Generalized Memory Effects. Mathematics, 13(21), 3409. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13213409