1. Introduction

Accurate segmentation of the hippocampus in three-dimensional MRI scans is critical for early diagnosis and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease. Automated methods based on three-dimensional (3D) U-Net architectures often achieve high performance in well-preprocessed research datasets. For example, DeepHipp, a 3D dense-block network with attention mechanisms, reported a Dice score of approximately 0.836 on curated multi-center data [

1]. Similarly, our previous work using a resource-efficient 3D U-Net on the HarP clinical dataset achieved a Dice score of 0.88 [

2].

Although many 3D-like U-Net variants have been proposed in broader areas such as volumetric or video data processing, we focus here on U-Net architectures that are directly applied to hippocampal segmentation. Using this established baseline ensures fair comparison with recent works and allows us to isolate the effect of preprocessing pipelines without introducing additional variables from more complex architectures.

The success of these models depends heavily on complex preprocessing pipelines. These pipelines often include skull stripping, intensity normalization, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE), and wavelet-based denoising. While these steps aim to enhance anatomical details and reduce image noise, their individual contributions to model performance have not been systematically evaluated. There are no ablation studies isolating the impact of full preprocessing (FP) versus no preprocessing (NP), especially across different datasets [

3].

Another challenge arises from domain shifts between datasets. Images from different scanners, sites, or protocols exhibit substantial variability, making models trained on one set less effective on others. Although transfer learning has been proposed to address this issue, the interaction between preprocessing and model adaptation remains unclear. A CapsNet-3D model recently achieved Dice scores up to 0.92 on Alzheimer’s classification tasks, showing promise for domain robustness, but it did not analyze the role of preprocessing in that context [

4].

In addition to these examples, a number of recent studies have advanced hippocampal segmentation through variations of U-Net and related architectures. Yang et al. [

5] proposed an improved 3D U-Net with attention mechanisms, reporting Dice scores above 0.86 on multi-center MRI data. Widodo et al. [

6] applied transfer learning with volumetric U-Net models, demonstrating that pretrained weights improved performance when adapting across datasets. Qiu et al. [

7] introduced a multitask edge-aware framework that enhanced boundary delineation in hippocampal segmentation. Prajapati and Kwon [

8] developed SIP-UNet, which processed sequential inputs in parallel to improve brain tissue segmentation more broadly, while Sghirripa et al. [

9] evaluated deep learning and subfield-specific methods for hippocampal segmentation across multiple protocols. Collectively, these works highlight progress in network design and training strategies. However, relatively few studies have systematically assessed how preprocessing pipelines—such as normalization, histogram equalization, or wavelet filtering—affect segmentation outcomes across datasets.

Our study addresses these gaps by performing a rigorous ablation analysis of preprocessing pipelines and their effect on both in-domain and cross-domain performance. We compare FP (CLAHE, 3D wavelet filtering) with NP (raw MRI volumes only normalized) across two datasets: HarP (clinical) and MSD (multi-center). We also evaluate how preprocessing affects transfer learning performance by fine-tuning MSD-trained models on HarP under both pipelines.

We measure outcomes using standard metrics, such as Dice coefficient, Jaccard index, Hausdorff distance, over- and under-segmentation ratios. We validate results with Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and provide qualitative overlays of segmentation outputs to illustrate visual differences.

This work offers the first controlled evaluation of how preprocessing affects both segmentation performance and cross-domain adaptability. Our findings will guide practical preprocessing choices for deep learning-based hippocampal segmentation in real-world clinical and research settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

We used two MRI datasets for hippocampus segmentation: The EADC-ADNI Harmonized Hippocampal Protocol (HarP) dataset [

10,

11] includes clinical T1-weighted MRIs. To focus on the region of interest and standardize model inputs, all images and labels were resized to a shape of (64, 64, 96). Each image and its label have shape (64, 64, 96). Voxel intensities range from 169.0 to 6409.0. Labels are binary: 0 for background, 1 for hippocampus.

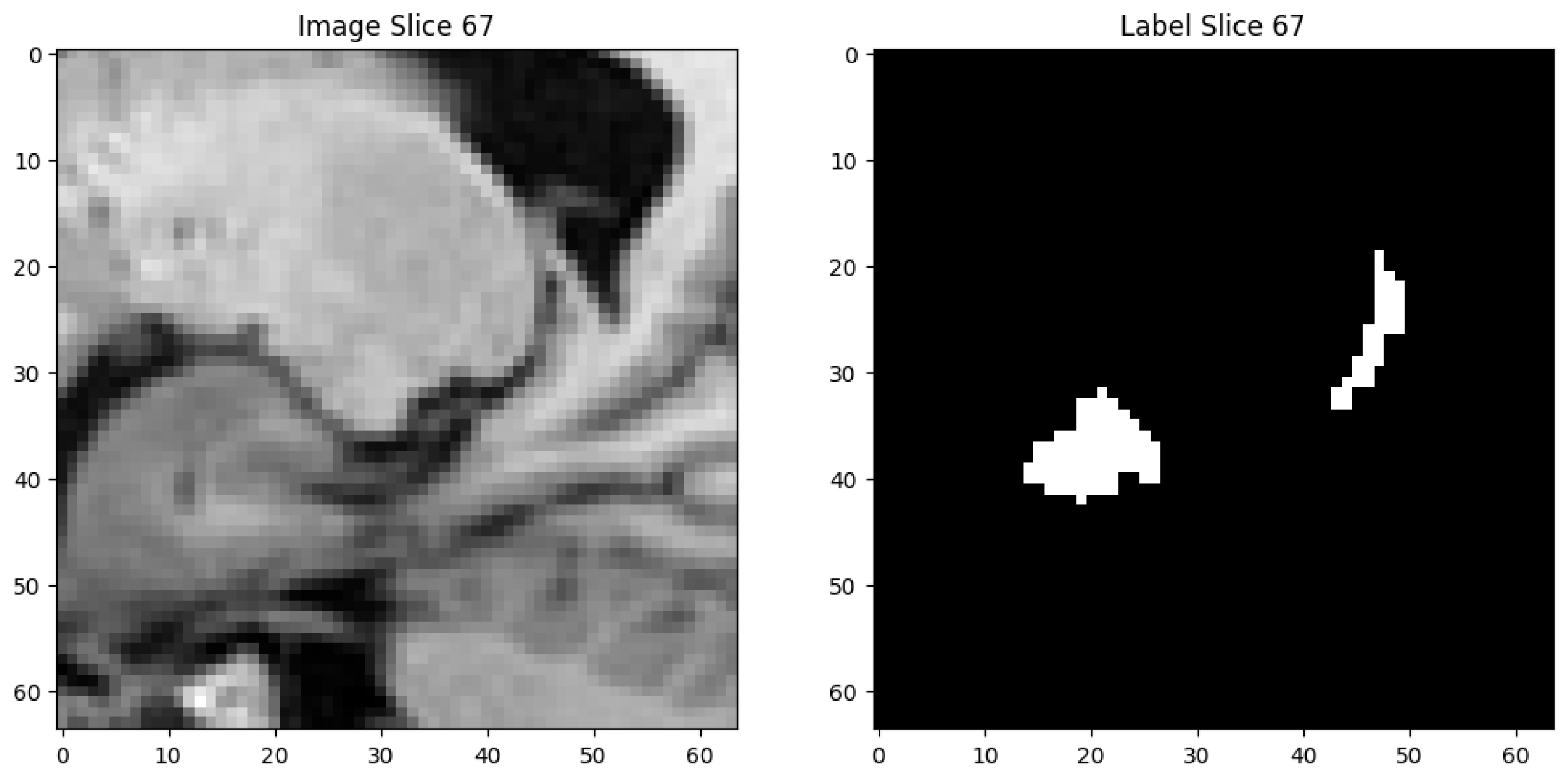

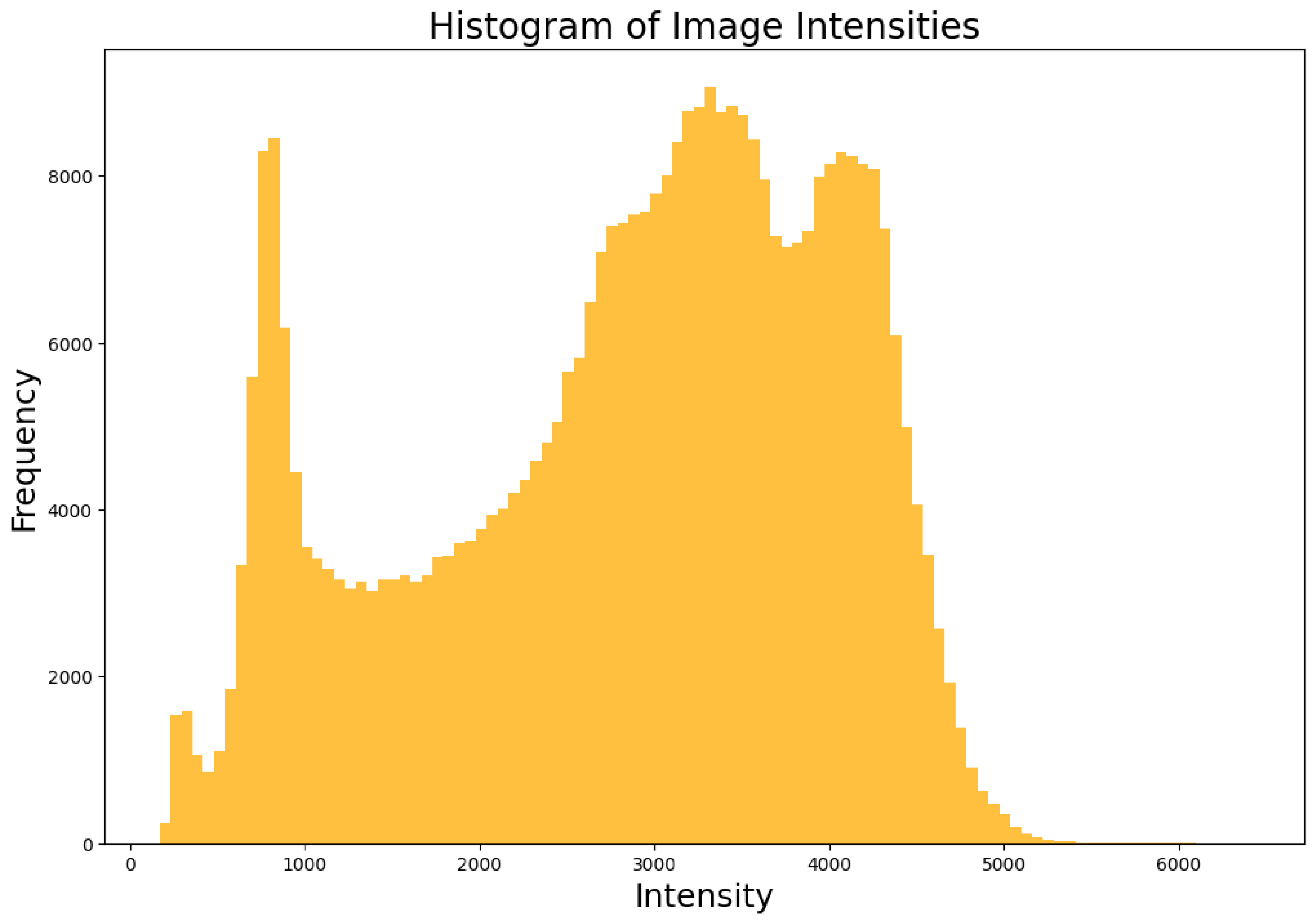

Figure 1 shows the image slice (slice 67) and its label highlighting the hippocampus location. An intensity histogram shows the distribution in

Figure 2.

The Medical Segmentation Decathlon (MSD) dataset [

12] is multi-center. It contains 260 volumes with varying original shapes. To standardize input, we padded all images and labels to a unified shape of (43, 59, 47), the maximum across volumes. Labels were binarized by merging anterior (1) and posterior (2) hippocampus classes shown in

Figure 3 into a single class (1 for hippocampus).

Summary statistics across MSD volumes show:

- 1.

Mean intensity: ~29,412

- 2.

Standard deviation: ~13,406

- 3.

Minimum intensity: 0

- 4.

Maximum intensity: ~1.7 million

- 5.

Label distribution: ~94.8% background and ~5.2% hippocampus post-binarization

Aligning image dimensions and label formats makes both datasets compatible. This setup supports both within-domain analysis and cross-domain transfer learning under consistent preprocessing conditions

2.2. Preprocessing Pipelines

We used two preprocessing pipelines to prepare the 3D MR images for segmentation: a Full Preprocessing (FP) pipeline and a No Preprocessing (NP) pipeline. Both were designed to ensure consistent input size and label formatting across datasets. The detailed steps for each pipeline are summarized in

Table 1.

Details:

We have broken down our preprocessing techniques into following major steps:

- 1.

CLAHE (Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization) [

13]

- a.

Scale intensities to [0, 1].

- c.

Apply 3D CLAHE with clip limit 0.03 to enhance contrast.

- 2.

SCE-3DWT (Selective Coefficient-Enhanced 3D Wavelet Transform)

- b.

Perform 3-level wavelet decomposition (Coiflet5).

- c.

Enhance detail coefficients by 0.8 and approximation coefficients by 0.4.

- d.

Reconstruct the volume and restore threshold.

- 3.

Padding/Cropping

- a.

HarP images are resized to (64, 64, 96); MSD images are padded to (43, 59, 47).

- b.

Ensures all volumes fit the 3D U-Net input requirement.

- 4.

Normalization & Binarization

- a.

Images are converted to float32 and normalized.

- b.

Labels are binarized: combining anterior and posterior hippocampus into one class for MSD.

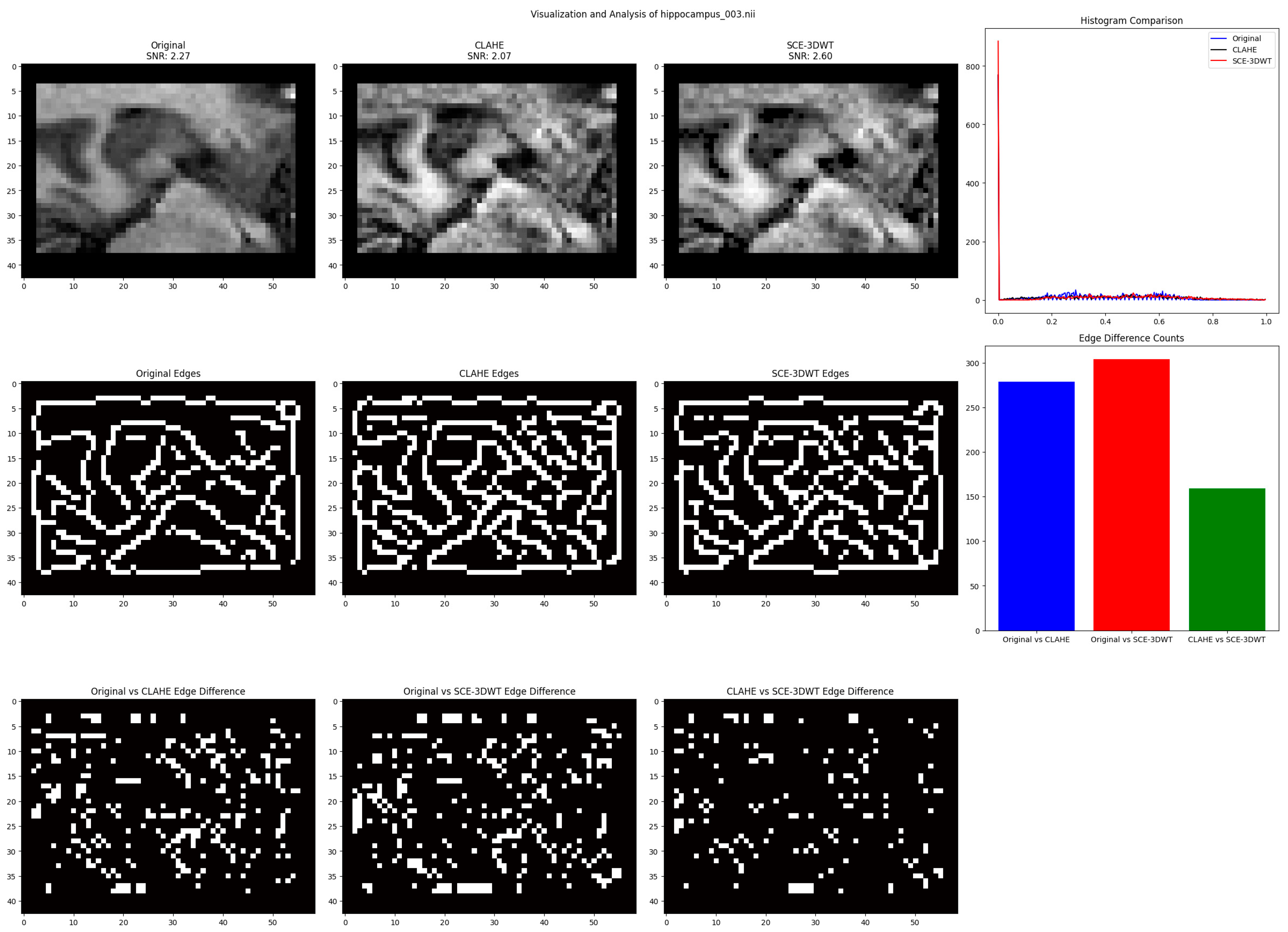

For validation and visualization, we processed three sample volumes from each dataset. Results show that the FP pipeline increased slice SNR from approximately 1.89 to 2.04 on HarP shown in

Figure 4 and from 2.27 to 2.60 on MSD shown in

Figure 5. Histograms indicate sharper peaks, and edge comparisons reveal that SCE-3DWT preserves structural details more effectively than CLAHE.

By restricting NP to normalization and resizing only, and matching dataset labels, we isolate the effects of contrast enhancement and wavelet-based filtering. This setup enables a clear evaluation of preprocessing benefits in downstream segmentation and transfer learning tasks.

2.3. Three-Dimensional U-Net Model Architecture and Training

We employed a custom 3D U-Net architecture for binary segmentation of the hippocampus (

Figure 6). The model follows the standard encoder–decoder design, enhanced with residual connections, instance normalization, and dropout for stability and regularization.

The encoder consists of five convolutional blocks. Each block applies two 3D convolutions followed by Instance Normalization, ReLU activation, and Dropout (abbreviated as IRD). Residual connections within each block improve gradient flow and reduce the risk of vanishing gradients. After each block, a 2 × 2 × 2 max-pooling layer halves the spatial resolution while doubling the number of channels, increasing representational capacity (progression: 32 → 64 → 128 → 256 → 512).

At the bottleneck layer, features are processed at 512 channels to capture high-level spatial context before reconstruction in the decoder.

The decoder mirrors the encoder using 2 × 2 × 2 transposed convolutions for upsampling. Skip connections link encoder and decoder blocks at the same resolution, allowing high-resolution spatial information to be preserved during reconstruction. Each decoder block applies two convolutional layers with IRD, progressively reducing the number of channels (512 → 256 → 128 → 64 → 32). A final 1 × 1 × 1 convolution maps the output to a single channel, producing the binary hippocampal segmentation mask.

This design balances accuracy with efficiency: residual connections and normalization enhance convergence stability, skip connections retain fine anatomical details, and dropout provides regularization. Overall, the architecture has 22.6 million trainable parameters, occupies ~86 MB in memory, and processes a single MRI volume in approximately 72.5 ms, making it suitable for clinical workflows.

2.3.1. Training and Setup of 3D U-Net Model

All experiments were implemented in PyTorch 1.12.1 + cu113 (+cu113 means the wheel was built with CUDA 11.3) using a batch size of 2. We optimized the model with Adam (learning rate = 1 × 10−3, weight decay = 1 × 10−4) and applied a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler (factor 0.1, patience = 2). Early stopping was triggered after 7 epochs without validation improvement, with a maximum of 250 epochs. Random seed was fixed at 42 for reproducibility. Training and transfer learning experiments were executed on two NVIDIA Quadro P4000 GPUs (8 GB each).

The following

Table 2 summarizes architecture and training details:

Data splitting followed consistent ratios:

HarP dataset (135 volumes): 80% training (108), 10% validation (13), 10% testing (14).

MSD dataset (260 volumes): 70% training (182), 15% validation (39), 15% testing (39).

We first trained models from scratch on MSD under both preprocessing pipelines—MSD FP and MSD NP. After convergence, these pretrained models were fine-tuned on HarP using the same respective pipelines (FP → FP and NP → NP). Transfer learning reused the full model weights, with the same optimizer, learning rate, scheduler, and early stopping settings.

2.3.2. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.9.13 using PyTorch for model development and training. Model training and inference were performed on a workstation equipped with two NVIDIA Quadro P4000 GPUs (8 GB each) and 64 GB RAM, with CUDA enabled for acceleration.

Data processing and deep learning workflows were managed using Visual Studio Code v1.104.1 and Jupyter Notebooks v2025.8.0. Data was split into training, validation, and test sets in a deterministic manner, ensuring the same split for every experiment. Batch size was fixed at 2 for all loaders.

2.4. V-Net Model Architecture and Training

To examine whether the effect of preprocessing is dependent on network architecture, we implemented a 3D V-Net backbone as an alternative to the 3D U-Net described in

Section 2.3. V-Net is a fully convolutional encoder–decoder architecture designed for volumetric segmentation. Unlike U-Net, which integrates residual connections in its convolutional blocks, V-Net employs standard convolutional blocks with deconvolution-based up-sampling to preserve spatial context across scales.

2.4.1. Architecture

The model takes a single-channel input volume of size 64 × 64 × 96. The encoder path consists of three convolutional stages with feature map sizes 16, 32, and 64, each followed by 2 × 2 × 2 max-pooling for down-sampling. A bottleneck stage with 128 feature maps captures high-level semantic information. The decoder path mirrors the encoder with three transposed 3D convolution layers for up-sampling, followed by convolutional blocks with 64, 32, and 16 filters. To restore spatial detail, skip connections are used to concatenate encoder and decoder features at matching resolutions. Unlike residual connections inside convolutional blocks, which directly add inputs to outputs, these skip connections simply pass multi-scale feature maps between network levels. A final 1 × 1 × 1 convolution produces a single-channel output map, followed by a sigmoid activation to generate voxel-wise hippocampus probabilities.Each convolutional block contains two consecutive 3 × 3 × 3 convolutions, each followed by instance normalization and ReLU activation. The complete network has approximately 1.4 million trainable parameters.

2.4.2. Training and Setup of VNET Model

The training configuration for the V-Net backbone was kept consistent with the U-Net experiments to enable a direct comparison. We trained with the Adam optimizer using a learning rate of 1 × 10

−3 and weight decay of 1 × 10

−4. Binary cross-entropy with logits (BCE) was used as the primary loss function; we also implemented a hybrid Dice + BCE loss, though BCE provided stable convergence. Training was performed for up to 250 epochs with a batch size of 2, using early stopping if validation Dice did not improve for 7 epochs. Mixed precision training (PyTorch autocast and gradient scaling) was enabled to improve efficiency. Only the best-performing model, defined by the highest validation Dice score, was saved for evaluation. The complete architectural and training setup for the 3D V-Net backbone is summarized in

Table 3.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluated segmentation performance using a comprehensive set of metrics.

Table 4 summarizes each metric and its meaning.

2.6. Study Workflow

To provide a clear overview of the methodology, we summarize the entire study pipeline in

Figure 7. The workflow begins with two datasets—HarP (clinical, resized to 64 × 64 × 96) and MSD (multi-center, padded to 43 × 59 × 47). Each dataset is processed under two alternative preprocessing pipelines: a Full Preprocessing (FP) pipeline including CLAHE and 3D wavelet filtering, and a No Preprocessing (NP) pipeline that uses only normalization.

Both pipelines were used to train two segmentation backbones: a custom 3D U-Net model with residual and skip connections (baseline) and a 3D V-Net model (alternate backbone check). Evaluation was performed under two scenarios: in-domain testing (training and testing within the same dataset) and transfer learning (pretraining on MSD and fine-tuning on HarP).

Results were assessed using overlap-based metrics (Dice, Jaccard, F1, Accuracy), boundary-based metrics (Hausdorff Distance, OSR, USR), statistical testing (Wilcoxon signed-rank test), and qualitative overlays. The workflow concludes with key findings, showing that NP generally outperforms FP on overlap metrics and also achieved lower Hausdorff distances, while FP retained a marginal advantage in under-segmentation.

3. Results

We present a comprehensive analysis of segmentation performance for both full preprocessing (FP) and no preprocessing (NP) pipelines on the HarP and MSD datasets. All results are reported for training, validation, and test sets, and are supported by statistical comparisons. We further analyze the effectiveness of transfer learning and benchmark our results against existing studies. Detailed qualitative visualizations and supplementary plots are provided where appropriate.

3.1. HarP Dataset: FP vs. NP

We compared the segmentation performance of full preprocessing (FP) and no preprocessing (NP) pipelines on the HarP dataset.

Table 5 presents the train, validation, and test set results for both pipelines.

NP achieved the highest test Dice (0.8876) and Jaccard (0.7981), with lower or comparable over- and under-segmentation ratios versus FP. Both approaches yielded high accuracy and low Hausdorff distance.

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to compare the NP and FP pipelines across all test samples. Results are summarized below in

Table 6:

Statistical analysis shows NP significantly outperforms FP for most overlap and region-based metrics (Dice, Jaccard, OSR, USR, accuracy, F1, and loss; p < 0.05). There was no significant difference in Hausdorff distance (p = 0.224), indicating boundary quality is comparable for both methods.

In summary, no preprocessing (NP) provides a measurable advantage over full preprocessing (FP) for hippocampus segmentation on HarP, with statistically significant improvements in most key metrics.

3.2. MSD Dataset: FP vs. NP

Table 7 summarizes the training, validation, and test results for both the no preprocessing (NP) and full preprocessing (FP) pipelines on the MSD dataset.

Both pipelines performed similarly on the test set. NP achieved a Dice of 0.8642, while FP reached 0.8601. Accuracy, Jaccard, F1, IoU, OSR, and USR scores were nearly identical across both approaches. The Hausdorff distance was also comparable.

To assess statistical significance, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed on the test set results for all key metrics shown below in

Table 8:

There was no significant difference between FP and NP in Dice, Jaccard, or F1 scores. NP achieved marginally higher accuracy and slightly better OSR and loss, while FP showed a small but statistically significant advantage in Hausdorff distance. However, these differences were minor.

It is noted that in some cases the test loss was lower than the training loss. This behavior is expected because dropout was applied during training but disabled during testing, which reduces noise and lowers loss. In addition, the test set was smaller and more homogeneous than the training set, which can also lead to lower loss values. These effects do not indicate bias or data leakage, and the statistical tests across all metrics confirm the robustness of the reported results.

In summary, on the large, multi-center MSD dataset, no preprocessing (NP) achieves results on par with or better than full preprocessing (FP) for nearly all segmentation metrics. Preprocessing did not lead to meaningful performance gains in this more heterogeneous data setting.

3.3. Transfer Learning: FP vs. NP

We evaluated the effect of preprocessing on transfer learning by fine-tuning models trained on the MSD dataset (source) to the HarP dataset (target), under both FP and NP pipelines. The key metrics for test performance are summarized in

Table 9 below.

Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (

Table 10 below) revealed that the NP pipeline performed significantly better than FP in most metrics: Dice, accuracy, F1, Jaccard, OSR, USR, and loss (all

p < 0.01). FP had a slightly lower Hausdorff distance, indicating marginally improved boundary accuracy, but the volumetric and region-based metrics consistently favored NP.

These results indicate that no preprocessing (NP) provides a measurable advantage for transfer learning from MSD to HarP, yielding significantly higher overlap, region accuracy, and lower loss compared to full preprocessing (FP). Only the Hausdorff distance was marginally better for FP, suggesting a minor benefit in boundary alignment, but this did not offset the overall gains observed with NP.

Although transfer learning is often associated with pretraining on very large datasets, such resources are not currently available for hippocampal segmentation. In practice, transfer between smaller datasets remains common in medical imaging because scanner protocols, populations, and acquisition settings still introduce significant domain shifts. Our MSD-to-HarP experiments reflect this setting, showing that even small-to-small transfer can yield measurable performance gains and provide insight into how preprocessing choices affect cross-domain adaptation.

Impact of Preprocessing in Transfer Learning

The findings suggest that extensive preprocessing is not required for optimal cross-domain adaptation in this setting. Models trained and fine-tuned with no preprocessing not only simplify the deployment pipeline but also deliver superior segmentation outcomes in key volumetric and regional metrics after transfer. This supports the use of streamlined dataset-agnostic workflows for multi-site or transfer learning applications in clinical MRI segmentation.

3.4. Qualitative and Visual Analysis

To supplement the quantitative findings, we performed qualitative analysis on representative test slices from both datasets. For the HarP dataset, slice 32 was selected; for the MSD dataset, slice 23 was used. Each comparison displays the ground truth label, the prediction from the no preprocessing (NP) model, and the prediction from the full preprocessing (FP) model.

In

Figure 8 below Both NP and FP models localize the hippocampus accurately. The NP prediction shows slightly better coverage of the true hippocampal region and fewer false positives, consistent with its higher Dice and Jaccard scores. The FP prediction is slightly more conservative, occasionally missing peripheral voxels.

On the MSD dataset,

Figure 9 shows that both pipelines capture the main hippocampal structure, but the NP model’s output aligns more closely with the ground truth boundaries. The FP result tends to slightly under-segment the region, which matches the observed lower Dice and Jaccard indices for FP on this dataset.

After transfer learning, the NP → HarP model prediction in

Figure 10 below covers the ground truth with high fidelity, showing less under-segmentation than the FP → HarP model. These observations are consistent with the quantitative results, where transfer learning using no preprocessing led to higher overlap and accuracy.

Across both in-domain and transfer learning scenarios, the NP pipeline yields predictions that generally better match the true hippocampal contours, reducing over- and under-segmentation errors (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). However, the FP pipeline demonstrates a consistent advantage in boundary alignment as compared to NP pipeline, as reflected by the significantly lower Hausdorff distance in both test and transfer learning results. This suggests that while NP achieves higher volumetric overlap and region-based scores, FP may help preserve finer edge details and improve boundary accuracy, especially in challenging or ambiguous cases. These visual trends reinforce the quantitative findings and highlight that the optimal preprocessing strategy may depend on whether overlap or boundary precision is prioritized in a given application.

3.5. Comparative Analysis

To evaluate the performance of our proposed approach, we compared its best-performing configuration, the No Preprocessing (NP) pipeline on the HarP test set, with three recent open-access journal studies and our own earlier work on HarP.

Table 11 summarizes the datasets, experimental setups, and key evaluation metrics. Since these studies used different datasets and experimental conditions, the reported values are not directly comparable; the table is provided to give context and illustrate that our approach achieves competitive performance despite lower resolution inputs and reduced model complexity.

3.6. Alternate Backbone (V-Net)

To examine whether the relative performance of FP and NP pipelines depends on the segmentation architecture, we repeated experiments using a 3D V-Net model (

Section 2.4). Results are summarized in

Table 12.

On the HarP dataset, V-Net reproduced the same trends observed with the U-Net backbone. The NP pipeline achieved higher Dice, Jaccard, F1, accuracy, and lower Hausdorff distance, demonstrating both superior volumetric overlap and more precise boundary localization. For example, on the HarP test set NP reached a Dice of 0.8833 versus 0.8683 for FP, a Jaccard of 0.7914 versus 0.7676, and a Hausdorff distance of 4.34 versus 4.67. FP showed a marginal advantage in under-segmentation ratio (USR), while NP reduced over-segmentation (OSR).

These results confirm that the superiority of NP is not restricted to the U-Net backbone but generalizes to the V-Net architecture, further strengthening the robustness of our conclusions.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effect of preprocessing pipelines on hippocampal segmentation performance using the HarP and MSD datasets. Two pipelines were compared: No Preprocessing (NP) and Full Preprocessing (FP), and a transfer learning setting from MSD to HarP was investigated. Performance was assessed using standard segmentation metrics, statistical significance testing, and qualitative visual analysis.

The results show that NP consistently achieved higher Dice, Jaccard, and F1 scores on the HarP dataset. For example, NP reached a Dice of 0.8876 on the HarP test set, outperforming FP with a Dice of 0.8753. Similar trends were seen for Jaccard and F1. Statistical testing confirmed these differences as significant for most overlap metrics. In contrast, FP achieved better Hausdorff Distance (HD) scores, indicating sharper and more accurate boundary localization, especially in challenging edge cases.

In the MSD dataset, the differences between NP and FP were smaller, and some metrics showed no significant change. This may reflect the more standardized acquisition and preprocessing of MSD images compared to HarP. Nevertheless, the HD advantage of FP persisted.

Transfer learning experiments from MSD to HarP revealed that NP-based fine-tuning achieved higher overlap metrics compared to FP-based fine-tuning. Dice for NP transfer reached 0.8843, while FP transfer reached 0.8736. All tested metrics showed significant differences, with NP outperforming FP in most cases except HD, where FP was superior. These results suggest that minimal preprocessing preserves domain-relevant features that are beneficial when adapting to a new dataset.

While these findings are promising, it should be noted that the domain shift between HarP and MSD may not fully capture the range of variability encountered in routine clinical practice, such as vendor-specific differences, motion artifacts, or older scanner protocols. In addition, the larger size of the MSD dataset compared with HarP introduces an imbalance that may influence transfer learning performance. Thus, the superiority of the NP pipeline should be interpreted in the context of the datasets tested, and further validation on broader and lower-quality datasets is needed to confirm robustness.

Qualitative results supported the quantitative findings. NP predictions generally aligned more closely with manual labels in terms of coverage, while FP predictions tended to capture boundaries with higher sharpness, reducing boundary errors. In some cases with irregular hippocampal shapes, FP produced better boundary adherence, explaining its lower HD values.

When compared to recent studies such as Yang et al. (2024) [

5], Widodo et al. (2024) [

6], and Qiu et al. (2021) [

7], our NP HarP configuration achieved higher Dice and Jaccard scores, despite using lower input resolution and a smaller model. Compared to our previous work on HarP, the proposed approach achieved higher overlap scores and lower HD, reflecting the benefits of architectural refinement and experimental design that included both in-domain and cross-domain evaluation.

These findings indicate that preprocessing strategies should be selected based on the target metric and deployment scenario. NP is advantageous for maximizing overlap-based accuracy, particularly in transfer learning scenarios. FP is preferable for tasks where precise boundary localization is critical.

This study contributes to the ongoing advancements in medical image segmentation, where specialized architectures are continually developed for targeted applications. For example, Prajapati and Kwon [

8] proposed the SIP-UNet architecture, which achieved high accuracy in brain tissue segmentation. Similarly, numerous works have focused on Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders by targeting the hippocampal region of the brain [

9,

14,

15,

16]. These efforts demonstrate the broad applicability of segmentation techniques across various brain regions and medical conditions.

Another consideration is that the architecture itself may contribute to the observed trends. The custom 3D U-Net employed here integrates residual connections and instance normalization, which are known to improve robustness to intensity variation and stabilize optimization. To address this concern, we repeated the experiments with a 3D V-Net backbone, which does not include residual connections inside convolutional blocks but relies on encoder–decoder skip concatenations. The results with V-Net reproduced the same trends as U-Net: NP achieved higher Dice, Jaccard, F1, accuracy, and lower Hausdorff distances, while FP retained a marginal advantage in under-segmentation. These consistent outcomes across two widely used backbones confirm that the observed NP advantage is not an artifact of a single architecture and strengthens the generalizability of our findings.

Limitations of this study include the use of only two datasets and binary hippocampal segmentation. The results may not generalize to multi-class hippocampal subfield segmentation or other brain structures. Additionally, no domain adaptation methods were applied, and only one network architecture was evaluated. Future work will explore multi-dataset training, harmonization techniques, and lightweight architectures to support deployment in resource-constrained clinical environments.

5. Conclusions

This work presented a systematic comparison of No Preprocessing and Full Preprocessing pipelines for 3D hippocampal segmentation using the HarP and MSD datasets. The evaluation included in-domain training, cross-domain transfer learning, statistical testing, and qualitative analysis.

No Preprocessing consistently outperformed Full Preprocessing in Dice, Jaccard, and F1 metrics, especially on the HarP dataset and in transfer learning from MSD to HarP. Full Preprocessing delivered superior Hausdorff Distance, indicating better boundary precision. The choice between NP and FP should therefore depend on whether overlap accuracy or boundary precision is prioritized.

Compared to recent open-access studies and our own previous work, the proposed approach achieved competitive or superior results while maintaining lower input resolution and model complexity. This demonstrates the effectiveness of targeted preprocessing evaluation and transfer learning strategies for hippocampal segmentation.

The study contributes practical guidance for selecting preprocessing pipelines in clinical and multi-center neuroimaging workflows. Importantly, the consistency of NP’s advantage across both U-Net and V-Net backbones suggests that the findings are robust to network architecture and not restricted to a single model design.

6. Availability of Data and Code

The Medical Segmentation Decathlon (MSD) dataset used in this study is publicly available at

http://medicaldecathlon.com/ (accessed on 24 July 2025).

The HarP dataset can be accessed by qualified researchers upon request through the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) portal (

https://ida.loni.usc.edu/login.jsp?project=ADNI) (accessed on 3 August 2025) and the Harmonized Hippocampal Protocol resource (

http://www.hippocampal-protocol.net/SOPs/index.php) (accessed on 3 August 2025). In accordance with ADNI/LONI policy, redistribution or resharing of the dataset or its derivatives is not permitted. The processed versions used in this study can therefore not be shared directly, but can be reproduced by downloading the original HarP data from ADNI/LONI and applying the resizing and preprocessing steps described in

Section 2.2.