Secure Chaotic Cryptosystem for 3D Medical Images

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Need for Encrypting Private Medical Images

1.1. Peculiarities of Medical Images

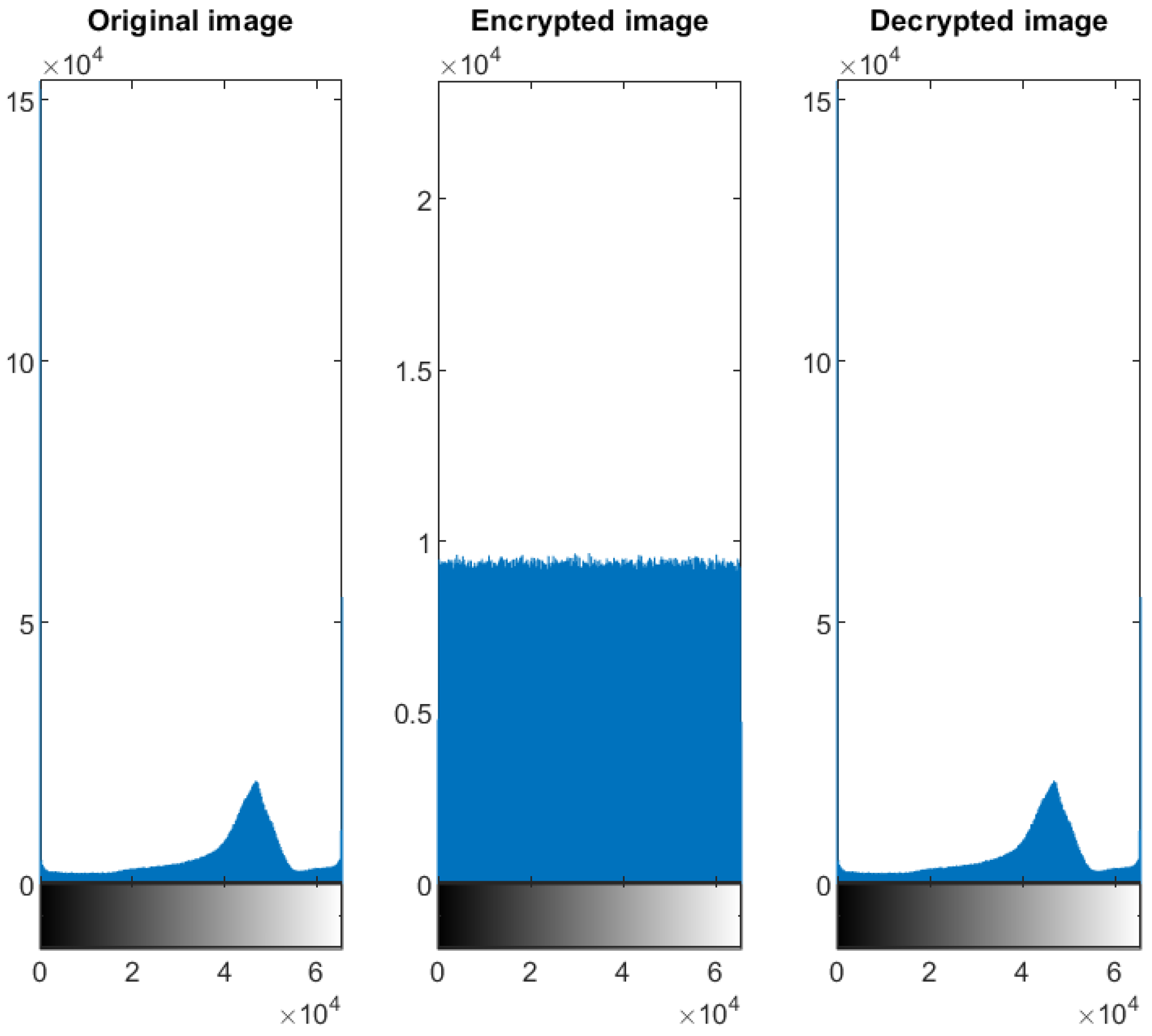

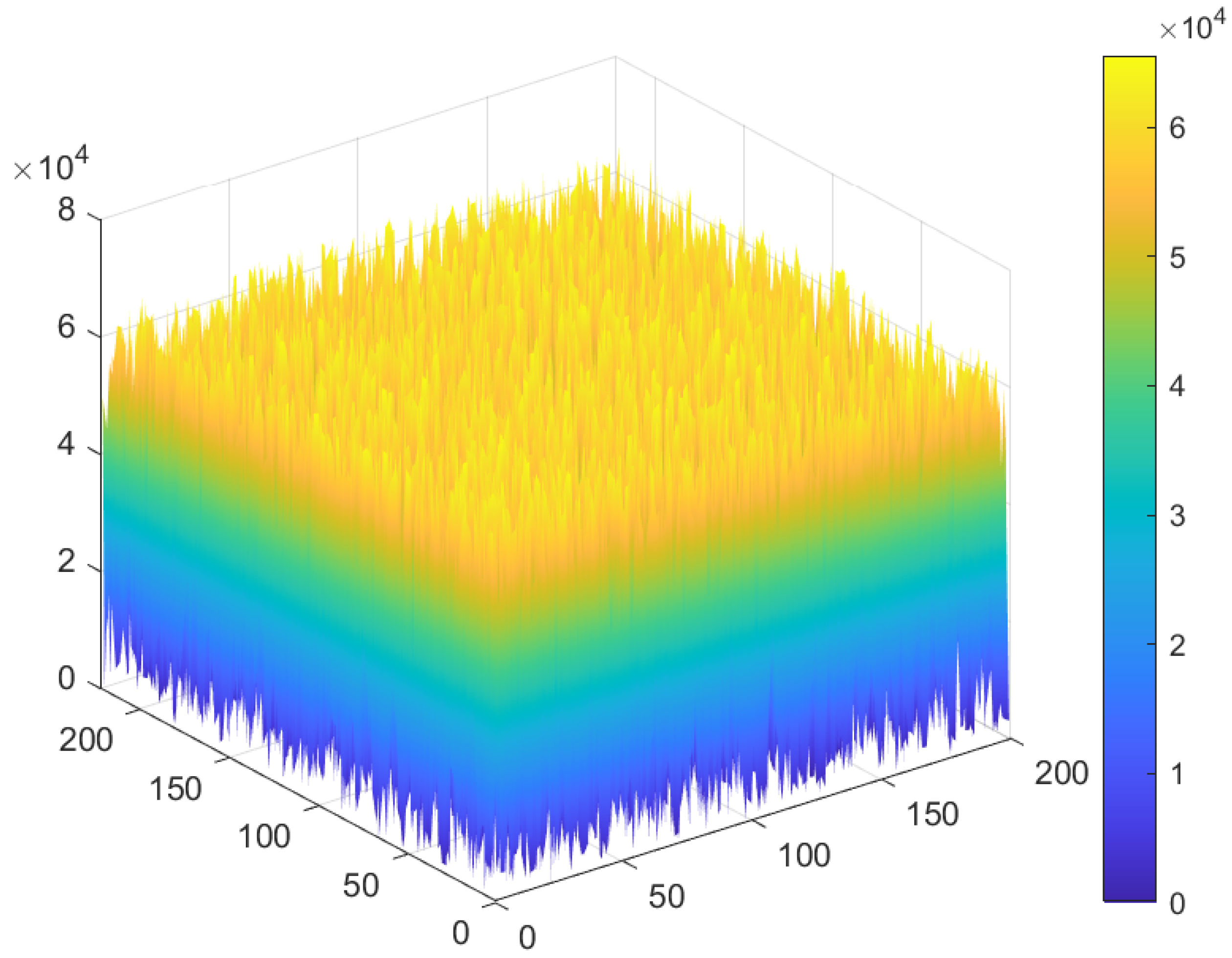

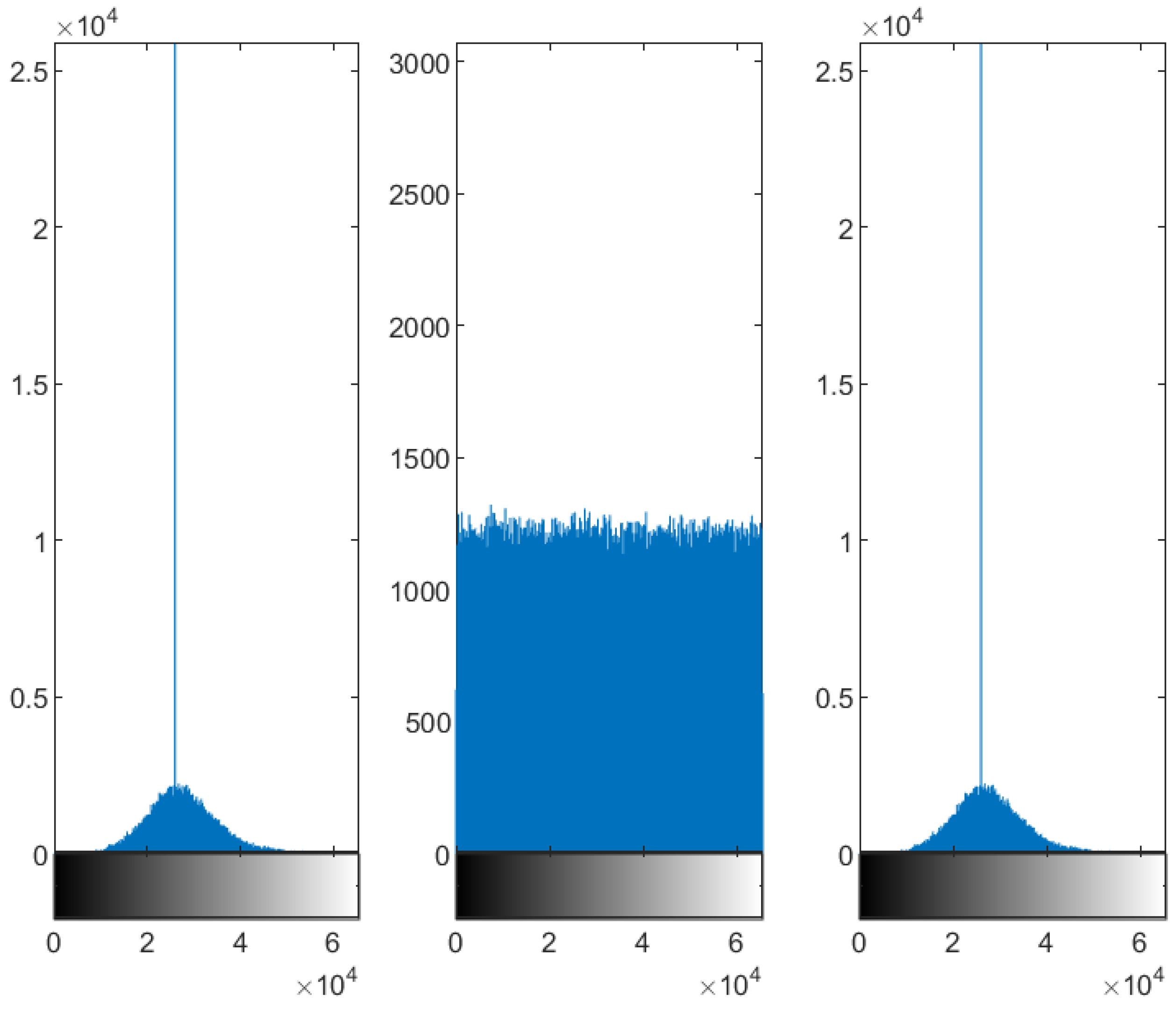

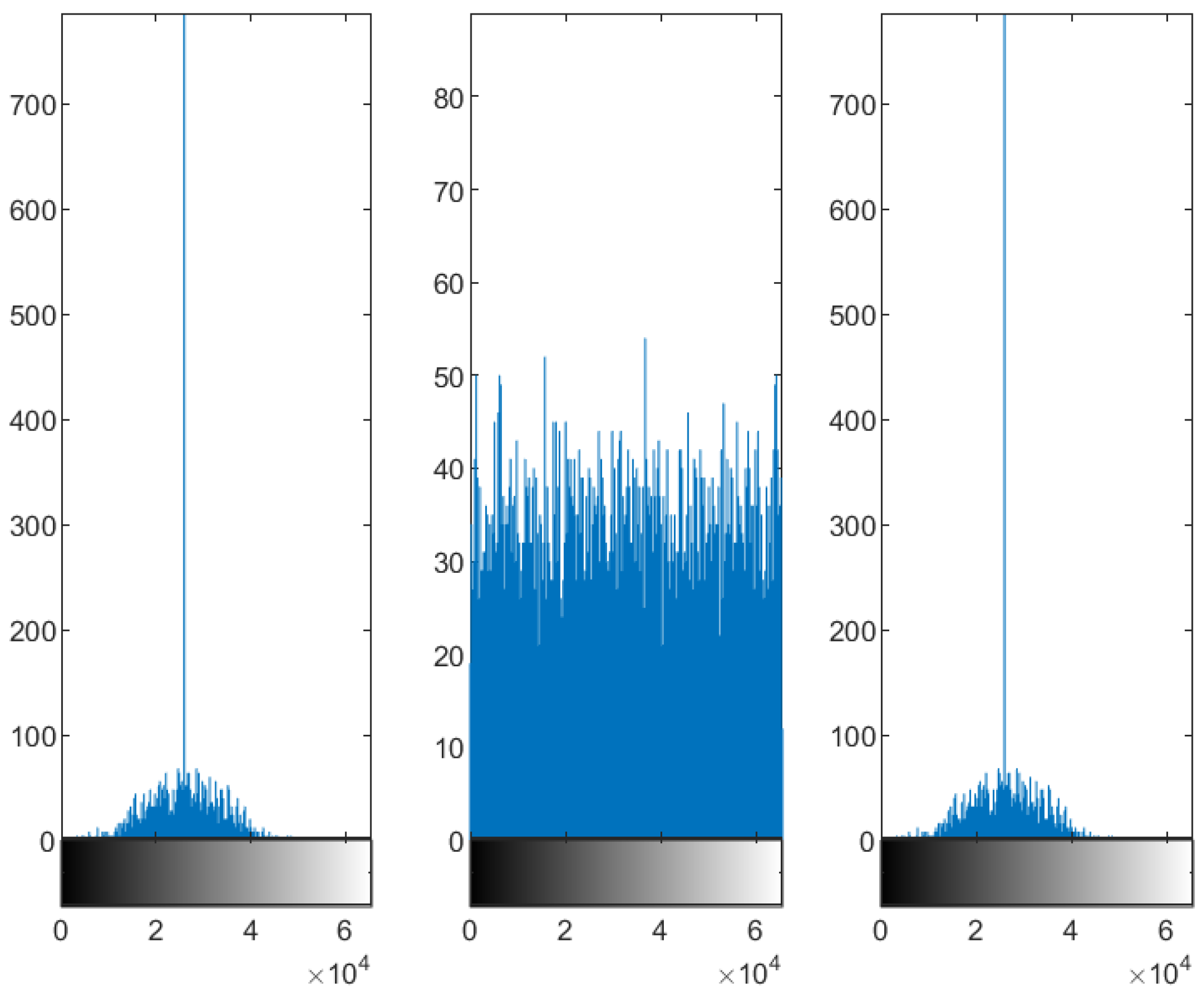

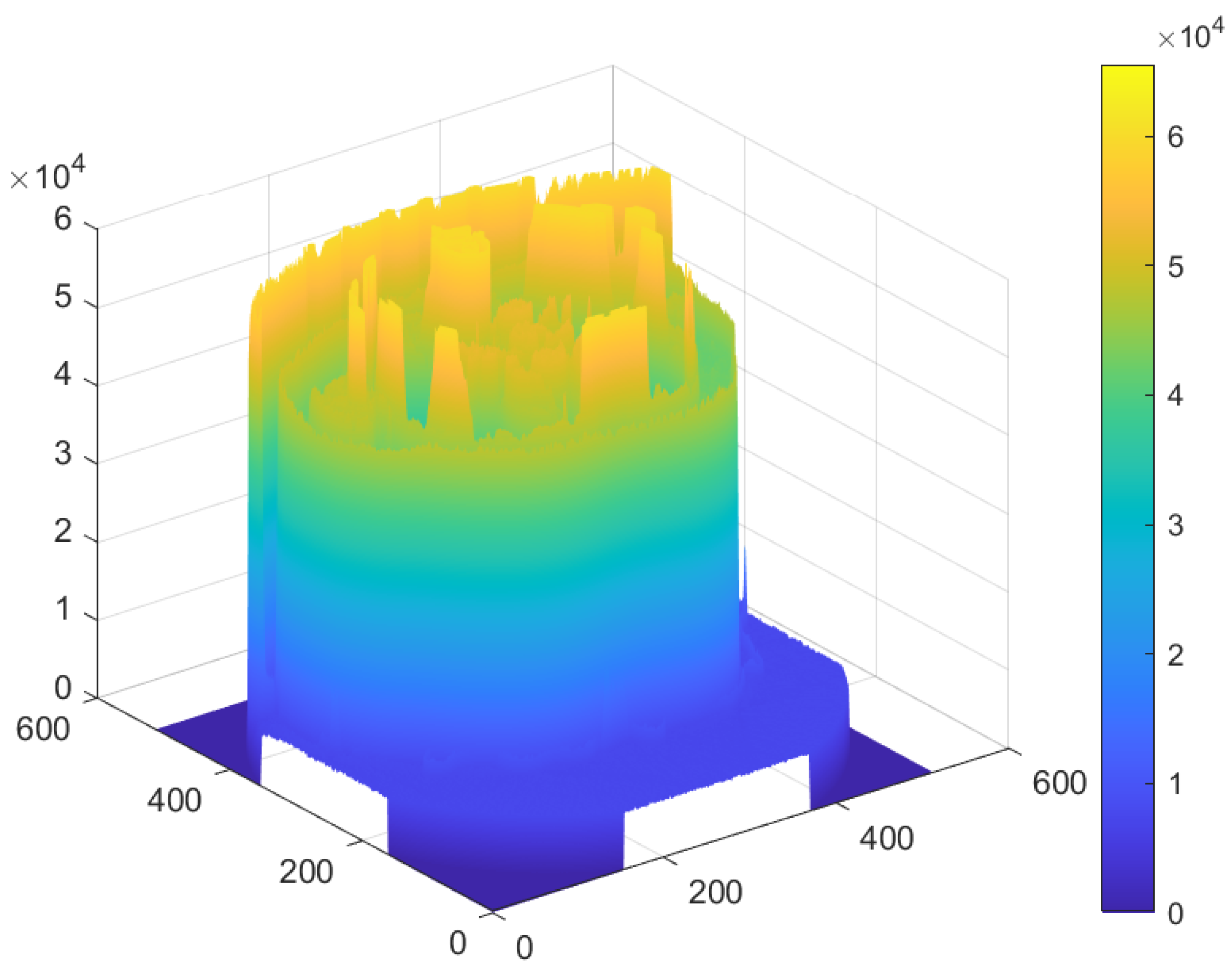

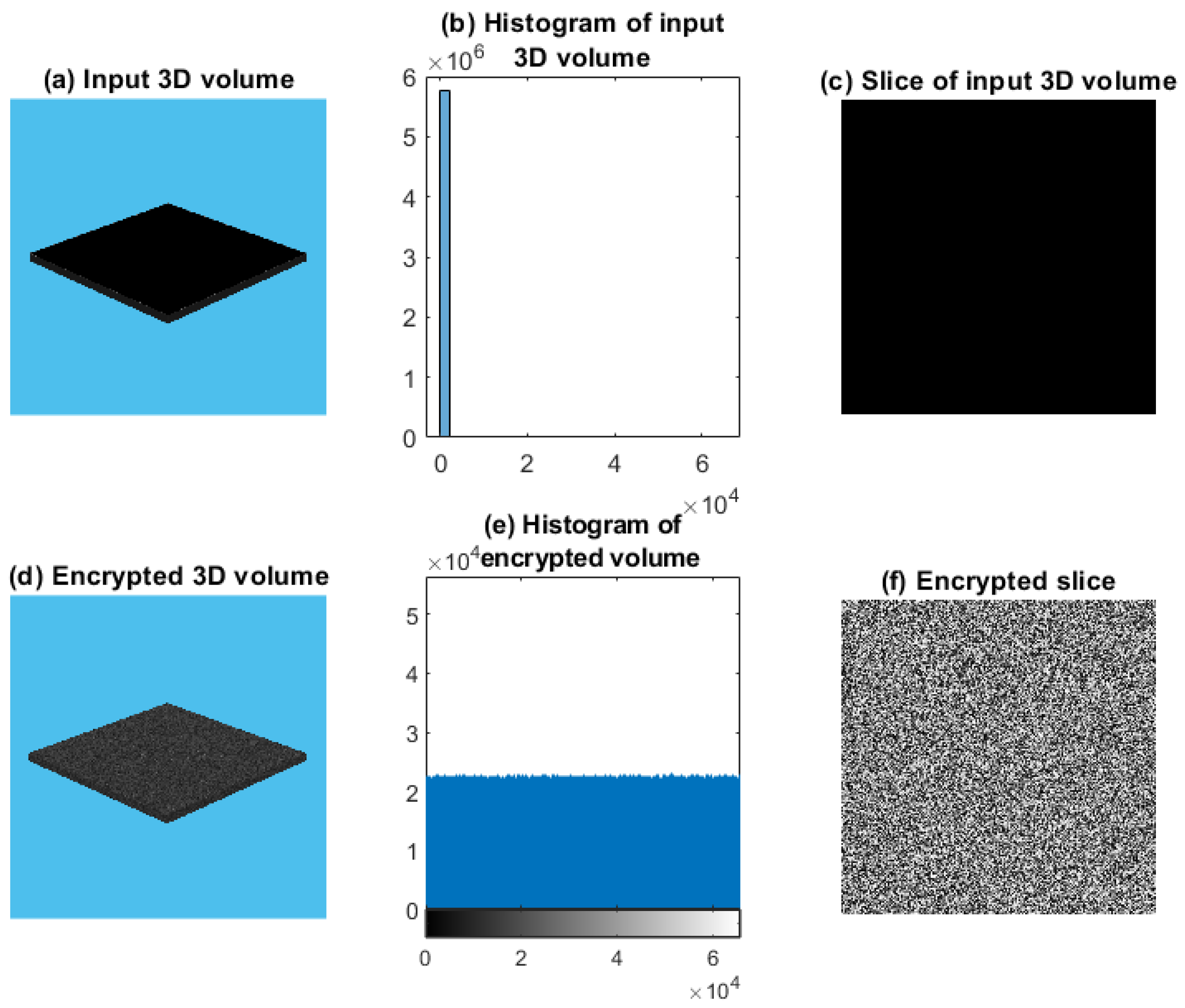

Differences Between Medical and Photographic Image Histograms

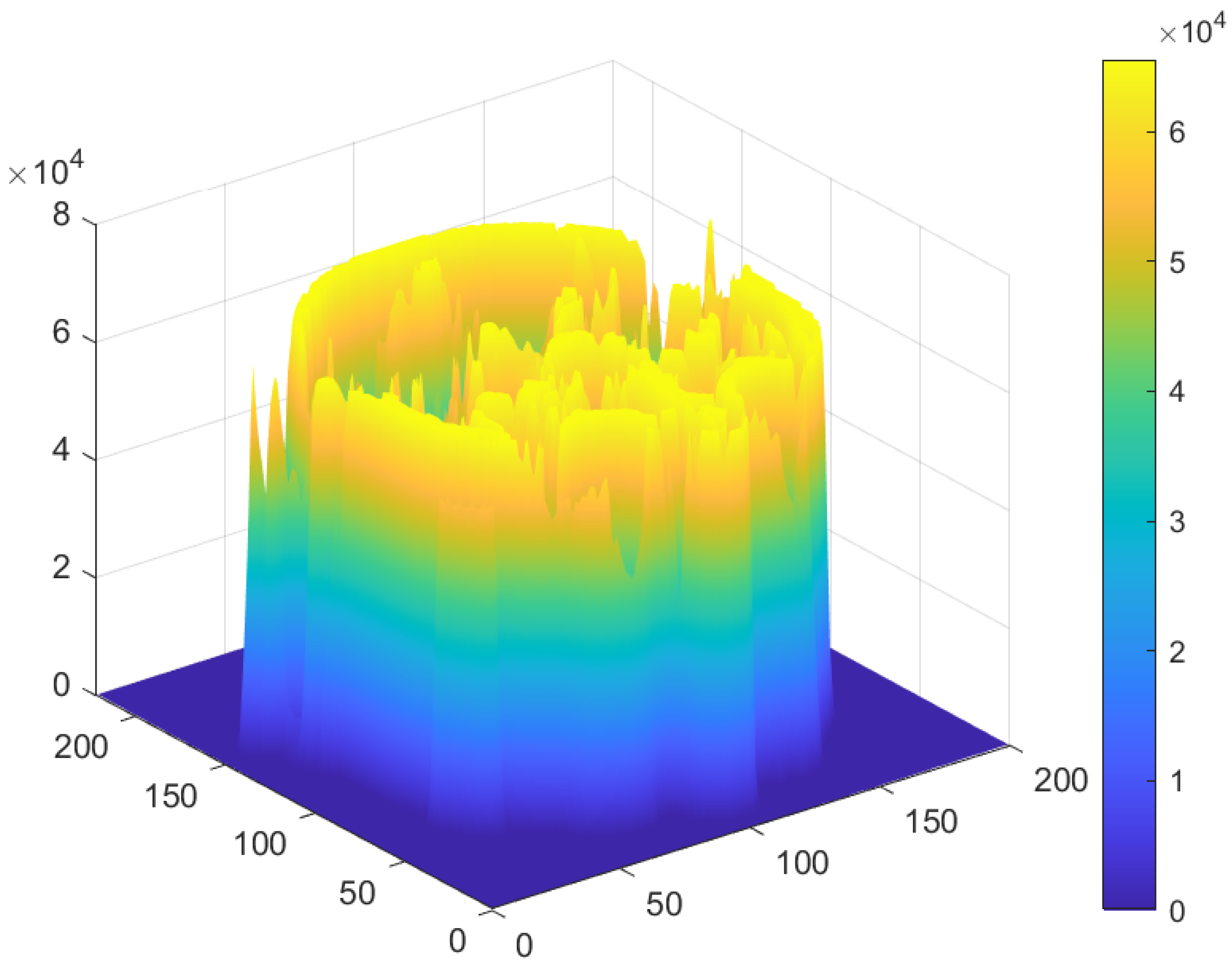

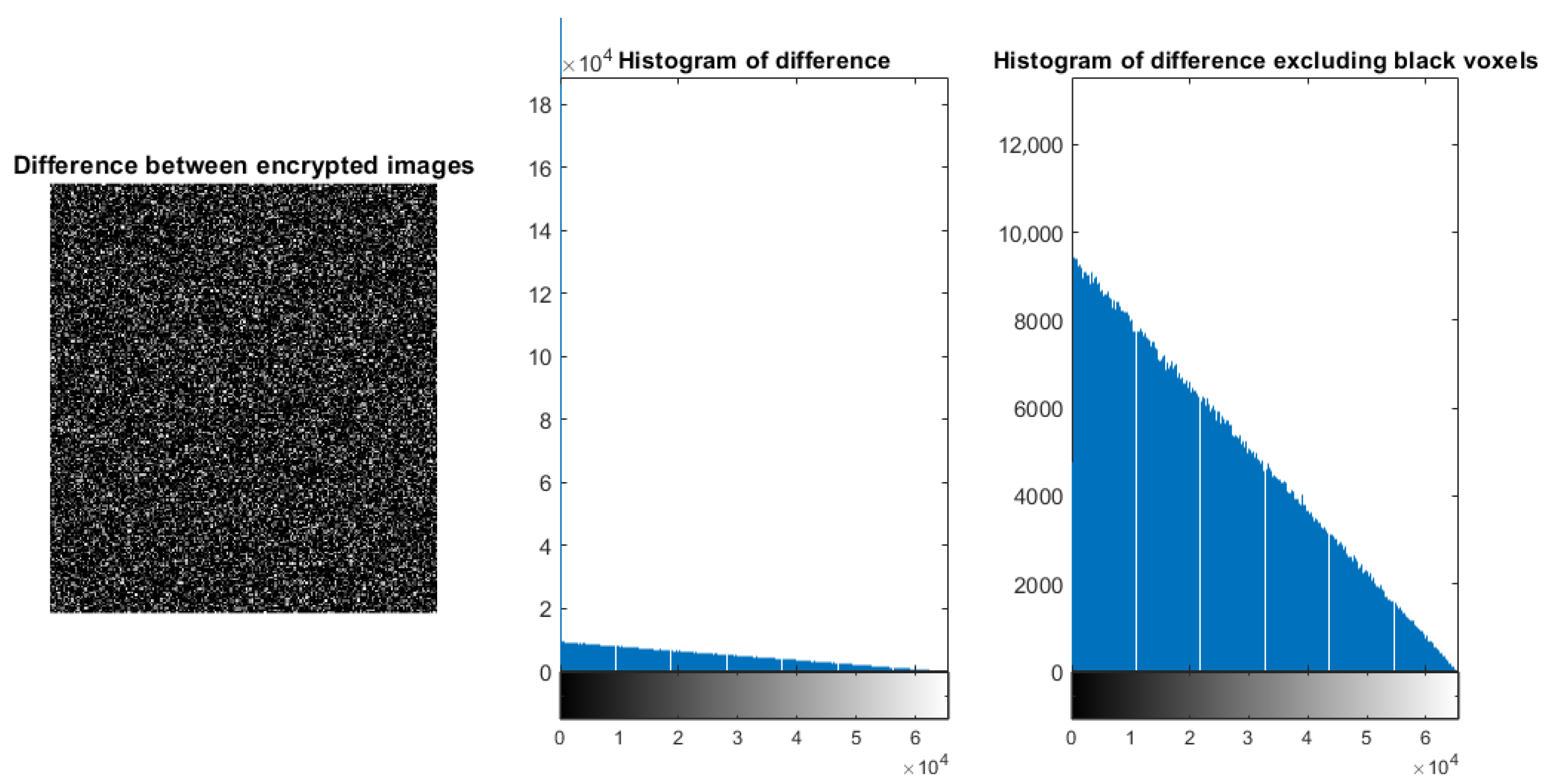

- Background regions (outside the body) are typically zero-padded, resulting in a dominant peak at X = 0 (black).

- Only voxels within the scanned anatomy (e.g., tissues, organs) contain meaningful, non-zero values.

1.2. Medical Image Formats and Standards

1.2.1. The DICOM Standard for Medical Imaging

1.2.2. The NIfTI Format for Medical Imaging

- NIfTI-1: The original format, typically using the .nii extension (a single file) or the .hdr/.img pair (two files).

- NIfTI-2: An updated version designed for larger datasets, with improved precision in spatial metadata.

- 1.

- Header and Image Data: Contains a header with metadata (e.g., image dimensions, voxel size, data type, orientation) and the actual image data.

- 2.

- 3D and 4D Support: Efficiently stores 3D volumes (e.g., structural MRI) and 4D data (e.g., time-series in fMRI).

- 3.

- Standardized Orientation: Uses a standardized coordinate system (e.g., RAS: Right-Anterior-Superior), improving compatibility with neuroimaging software like FSL, SPM, and AFNI.

- 4.

- Open and Simple: Designed to be platform-independent and easy to implement.

1.2.3. NIfTI vs. DICOM

1.2.4. Other Medical Formats

- 1.

- MINC (Medical Imaging NetCDF). Common features:

- Developed by the Montreal Neurological Institute.

- Based on NetCDF (Network Common Data Form).

- Flexible metadata support, useful in research environments.

- Less common now but still used in some academic pipelines.

- 2.

- NRRD (Nearly Raw Raster Data). Common features:

- Lightweight format for scientific and medical image data.

- Stores data and metadata in a single file (or paired files).

- Popular in open-source tools (e.g., 3D Slicer, ITK).

- Supports rich metadata, making it useful for processing and visualization.

1.3. Limitations of the Traditional Encryption Methods

1.4. Confusion and Diffusion

1.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics

- 1.

- Information Entropy of encrypted image;

- 2.

- Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR);

- 3.

- Unified Average Change Intensity (UACI);

- 4.

- Autocorrelation of pixels/voxels;

- 5.

- Fourier transformation analysis;

- 6.

- Mean Squared Error (MSE);

- 7.

- Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR).

1.6. Contribution of This Research

- 1.

- Support for multiple concurrent medical image formats.

- 2.

- A preprocessing stage offering several useful capabilities.

- 3.

- Double encryption leveraging chaotic and PRNG sequences.

- 4.

- Optimization of the chaotic RNG sequence through Lyapunov exponent maximization using either a genetic algorithm or a random walk.

- 5.

- Implementation of both ECB and CBC encryption modes.

- 6.

- Excellent performance in terms of entropy, UACI, NPCR, PSNR, and speed.

- 7.

- Enhanced overall security.

- 1.

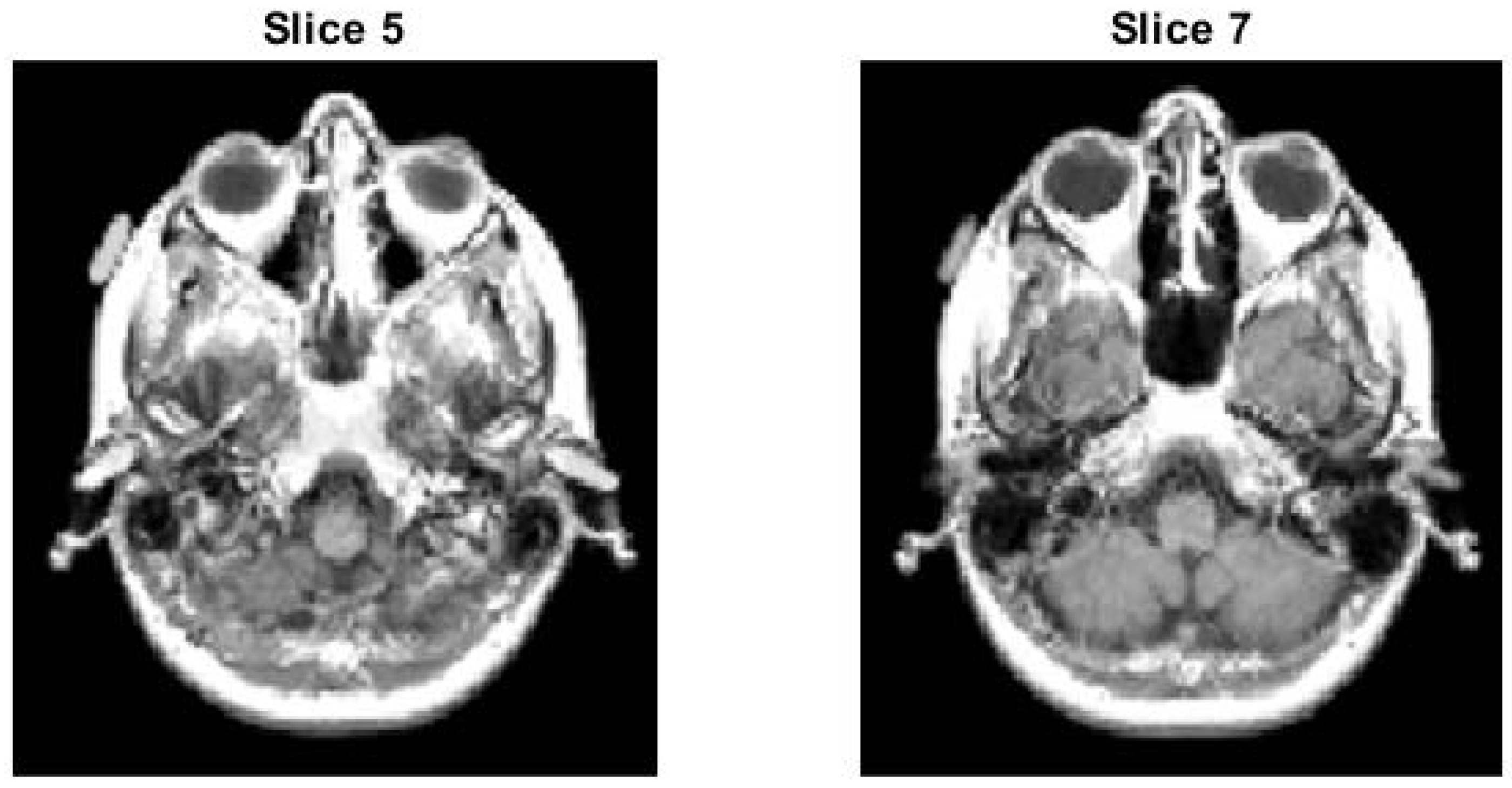

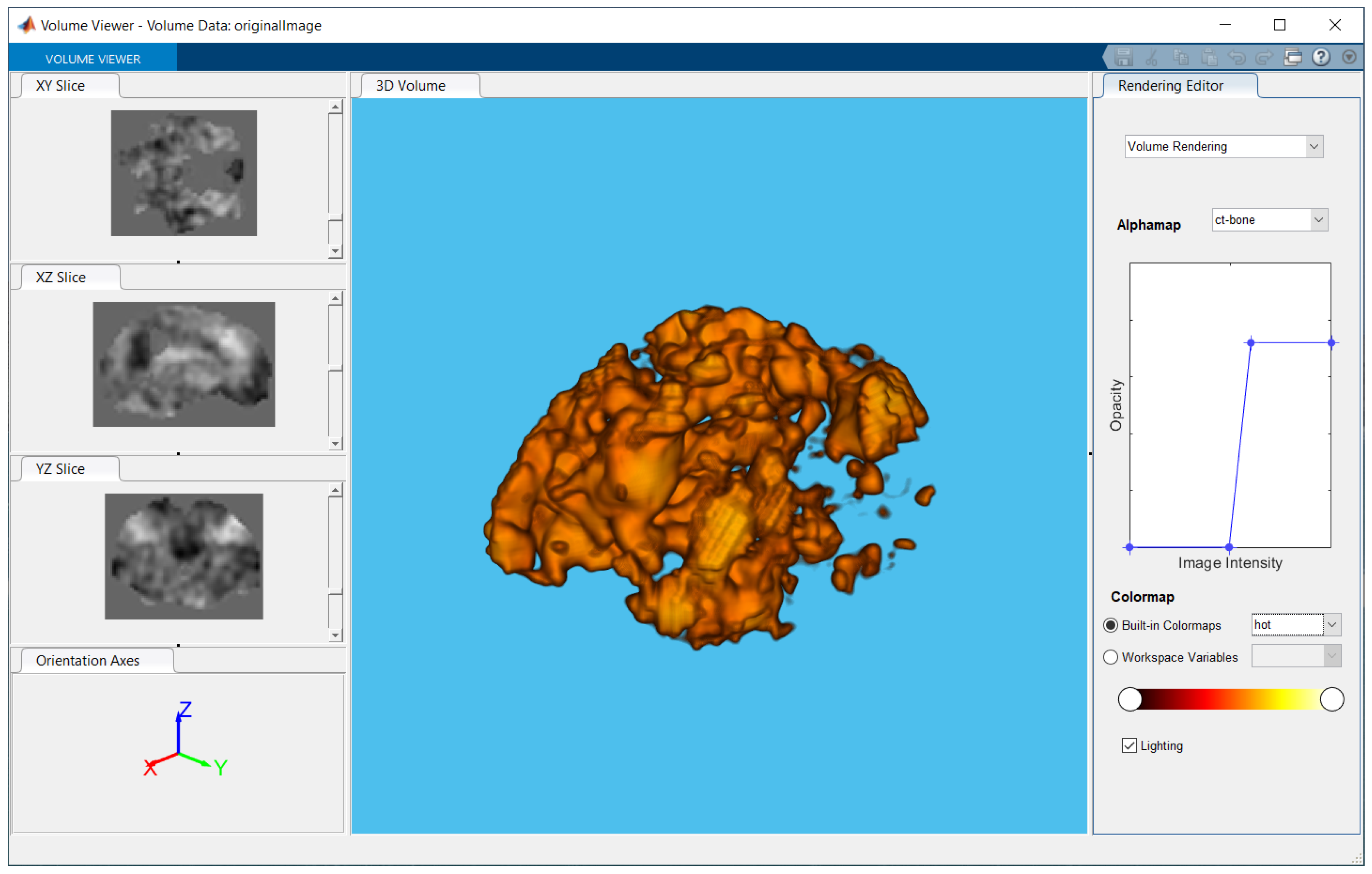

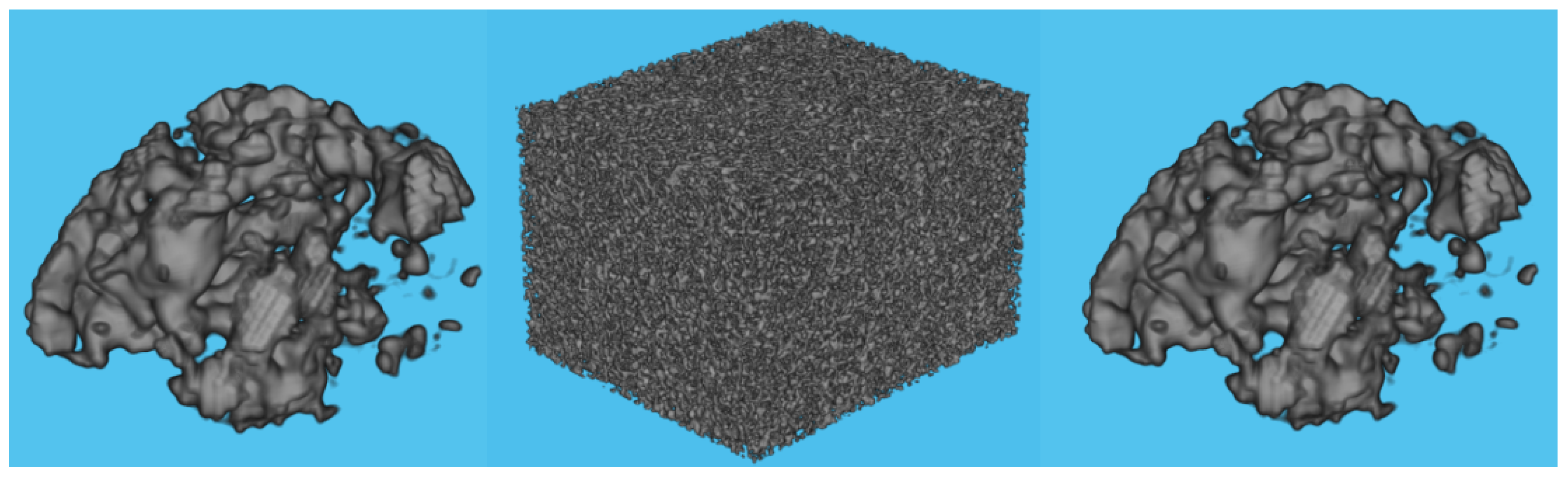

- Test image 1 is a 3D MRI scan of a portion of a skull, encoded in 8-bit unsigned integer (uint8) format.

- 2.

- Test image 2 is a 3D MRI scan of a skull volume stored in high-resolution NIfTI format, encoded as signed floating-point (’single’) values.

- 3.

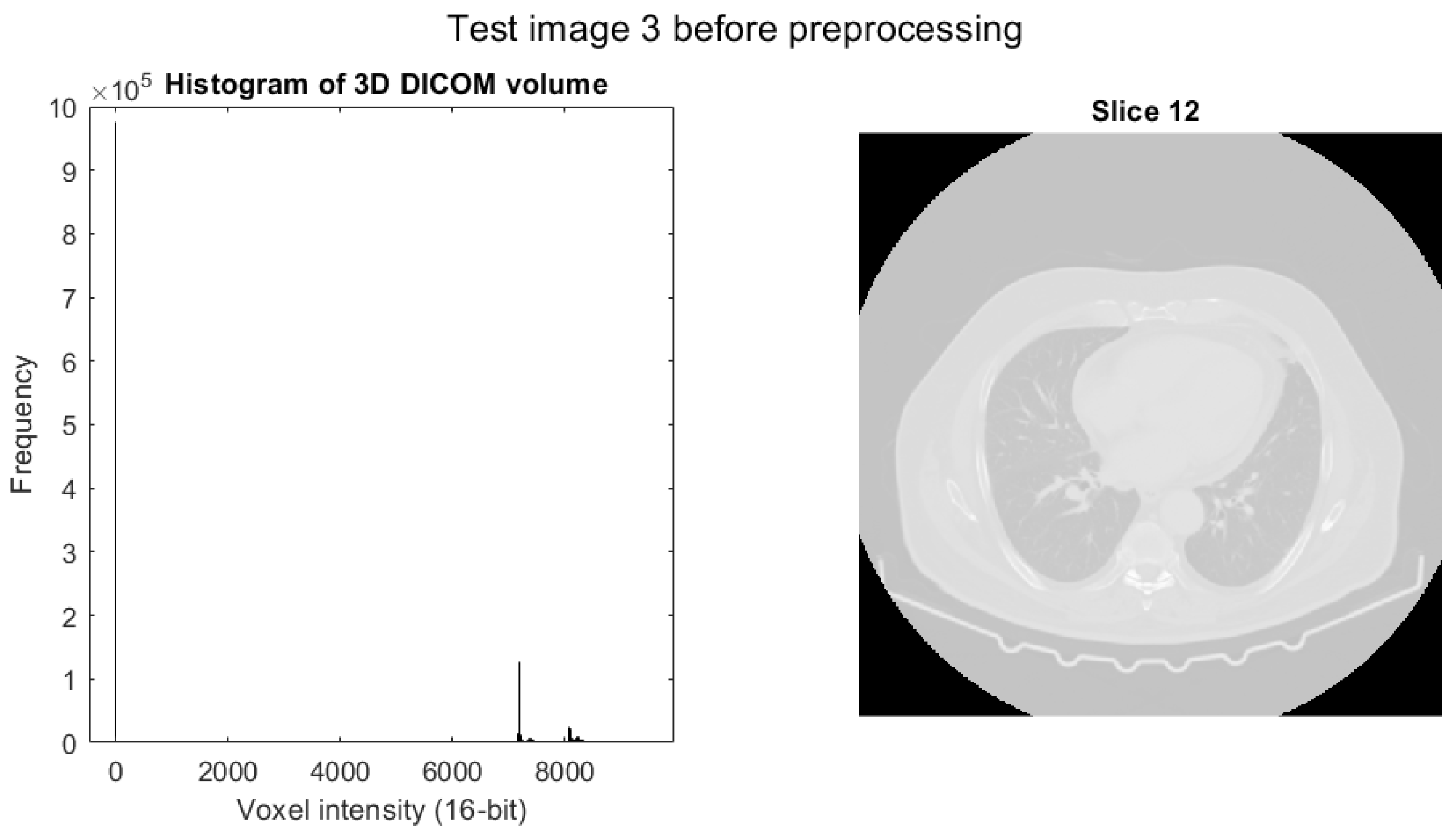

- Test image 3 is a 3D sub-volume extracted from a high-resolution CT scan of a human body, stored in DICOM format as a 16-bit unsigned integer (uint16) volumetric dataset.

1.7. Paper Structure

2. Related Work

2.1. Chaotic Image Encryption

- 1.

- One-dimensional chaotic systems containing only one independent variable, such as Hénon map, logistic map, sine map, etc. These systems are structurally simple, highly efficient in operation and exhibit diverse dynamical behaviors, but the key space is rather small, and their chaotic characteristics can be revealed by analyzing the bifurcation map, the periodicity, and so on. Hence, they are vulnerable to attacks.

- 2.

- Multi-dimensional chaotic systems involve multiple state variables and exhibit higher complexity, diverse dynamical behaviors and increased sensitivity to starting conditions, making them widespread in the field of image encryption. Examples include the Lorenz system, Chua system, Chen system, and hyper-chaotic systems (four or more dimensions).

2.2. Chaotic 2D Medical Image Encryption

2.3. Chaotic 3D Medical Image Encryption

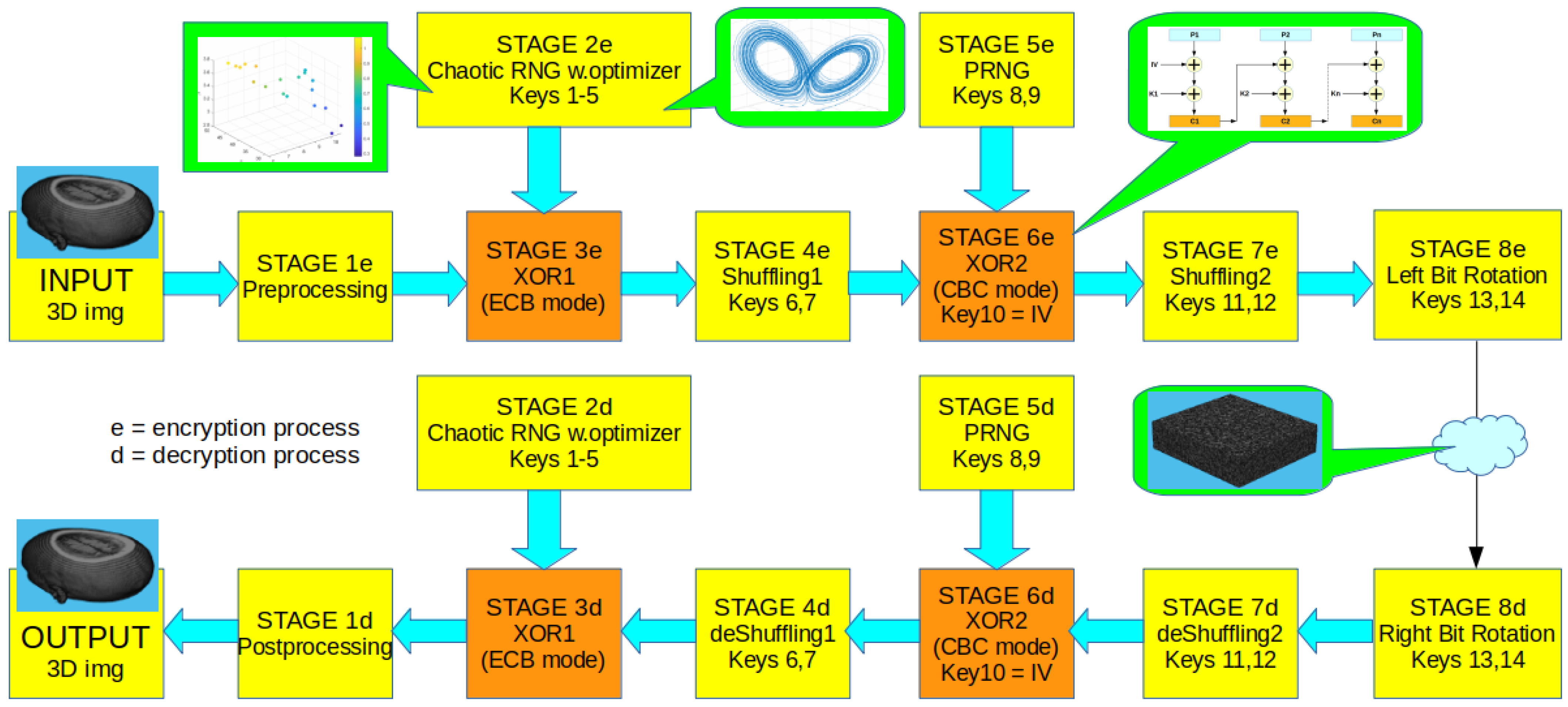

3. The Proposed Cryptosystem

3.1. Stage 1: Preprocessing

- 1.

- Removal of null slices from 3D input images across all three dimensions;

- 2.

- Conversion of 4D to 3D images (if needed);

- 3.

- Conversion of 3D image data from ’single’ or uint8 formats to uint16;

- 4.

- Rescaling of input 3D image to full scale (e.g., from 0–88 to 0–255 for test image 1);

- 5.

- Conversion of input 3D image to high resolution (optional; improves results);

- 6.

- Image rescaling based on histogram (optional; facilitates presentation);

- 7.

- Derivation of master key and subkeys for the various stages of processing.

Key Derivation

- Unpredictability: If the image is secret and high-entropy (random enough), its hash will also be unpredictable. But if the image is public or guessable (like a photo or a common test image), an attacker can try candidate images, compute their hashes, and attempt an attack.

- Non-reversibility: A strong cryptographic hash (e.g., SHA-256, SHA-512) makes it infeasible to recover the image from the hash.

- Obscurity: The relationship between the cipher image and the fourteen subkeys is complex, obscure, and non-invertible.

- Extra randomness: Without extra randomness (e.g., a salt), an attacker can precompute hashes for likely images.

- Uniqueness: Each key is unique, even if it concerns the same image.

- Resistance to differential attacks: even the slightest change in the plaintext images (typically, a one-bit modification) will result in a totally different encrypted image [19].

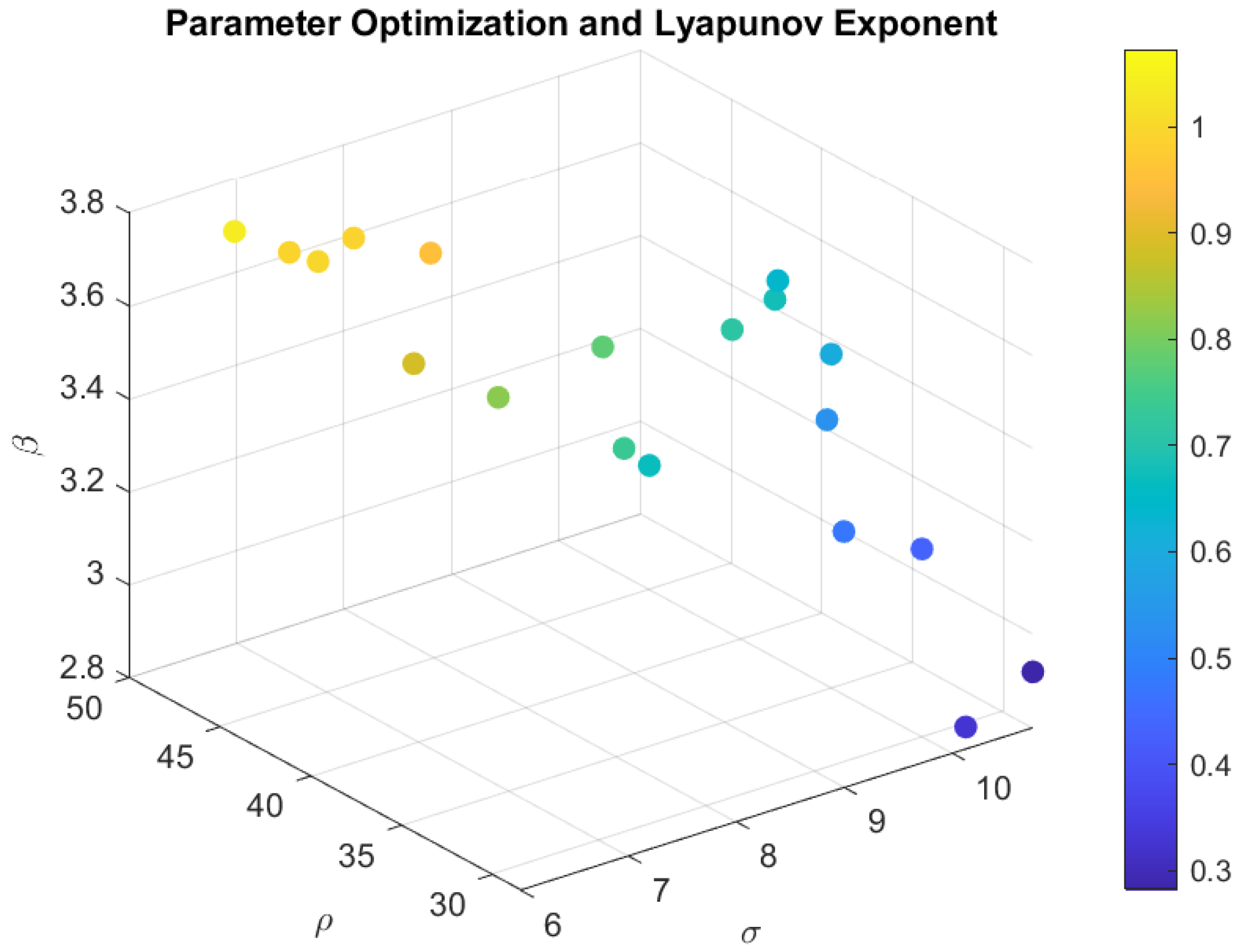

3.2. Stage 2: Generation of Chaotic Pseudorandom Numbers

3.2.1. Lorenz Chaotic System

- Largest Lyapunov exponent (λ1): Measures the average exponential divergence of nearby trajectories. If positive, the system is chaotic.

- Second Lyapunov exponent (λ2): Typically zero for continuous-time systems, corresponding to perturbations along the flow direction (time evolution).

- Smallest Lyapunov exponent (λ3): Strongly negative, reflecting contraction onto the attractor.

3.2.2. Generation of Quality Chaotic Sequences

- The system exhibits strong chaotic behavior.

- The system has better mixing properties, meaning that it explores its state space more thoroughly and rapidly.

- The dynamics are less predictable, which can be desirable in certain applications like cryptography and random number generation.

- High Lyapunov exponent improves diffusion and resistance to prediction.

3.2.3. Optimization Using a Genetic Algorithm

- range = [5, 25];

- range = [10, 50];

- range = [2, 4].

3.2.4. Optimization Using Random Walk

3.3. Stage 3: XOR Encryption of the 3D Image with Chaotic Noise

3.4. Stage 4: Shuffling of the ECB-Encrypted Image

3.5. Stage 5: Generation of the CBC Encryption Key

3.6. Stage 6: XOR Encryption with Pseudorandom Numbers in CBC Mode

- : ciphertext block;

- : plaintext block;

- : previous ciphertext block (or IV for the first block);

- : subkey , a pseudorandom sequence block;

- ⊕: XOR operator.

- Each block is encrypted independently using the same key.

- Identical plaintext blocks produce identical ciphertext blocks; this makes it vulnerable to pattern leakage.

- ECB mode has poor diffusion: changing one bit in plaintext affects only one block in ciphertext.

- Small changes in key affect ciphertext only where that key is used, not across blocks.

- Chaining effect: Each ciphertext block depends on the previous ciphertext block. So, a change in plaintext or key affects all subsequent ciphertext blocks. CBC improves diffusion because each ciphertext block depends on all previous plaintext blocks; a small change in a pixel will propagate to all subsequent ciphertext blocks. This introduces avalanche behavior, which is the goal of diffusion [3].

- Better key sensitivity: A small change in key affects not only the block where it is used for but also propagates via chaining. This makes CBC much more sensitive to key changes than ECB.

- Stronger avalanche effect: A 1-bit change in plaintext or key leads to a completely different ciphertext for that and all following blocks. This is a desirable property in secure encryption.

3.7. Stage 7: Shuffling of All Voxels Randomly

3.8. Stage 8: Rotation of All Voxels Randomly to the Left

3.9. Use of Subkeys per Stage

- 1.

- Twister

- 2.

- SimdTwister

- 3.

- CombRecursive

- 4.

- MultFibonacci

- 5.

- V5uniform

- 6.

- V4

- 7.

- Philox

- 8.

- Threefry

4. Experimental Results

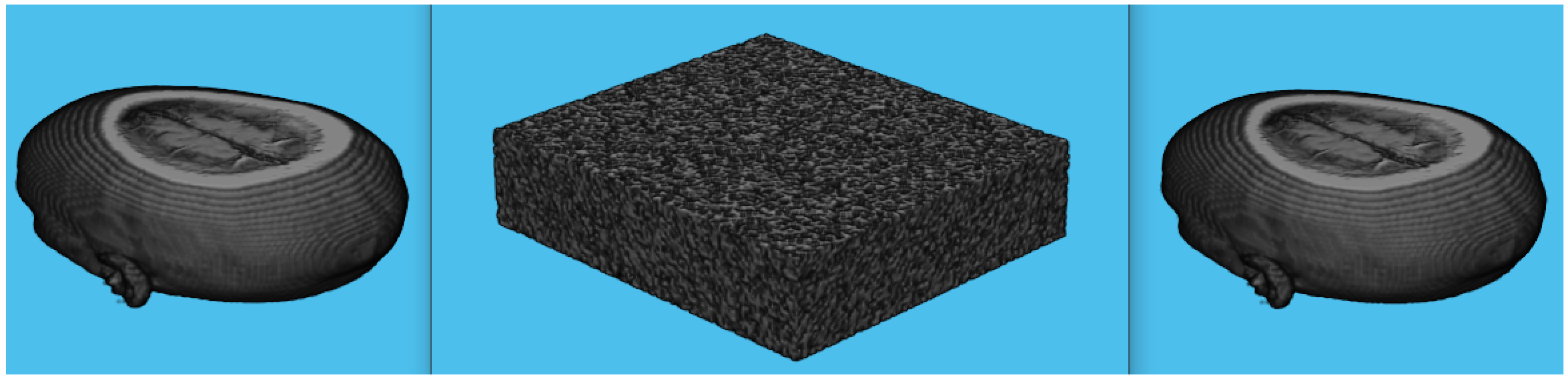

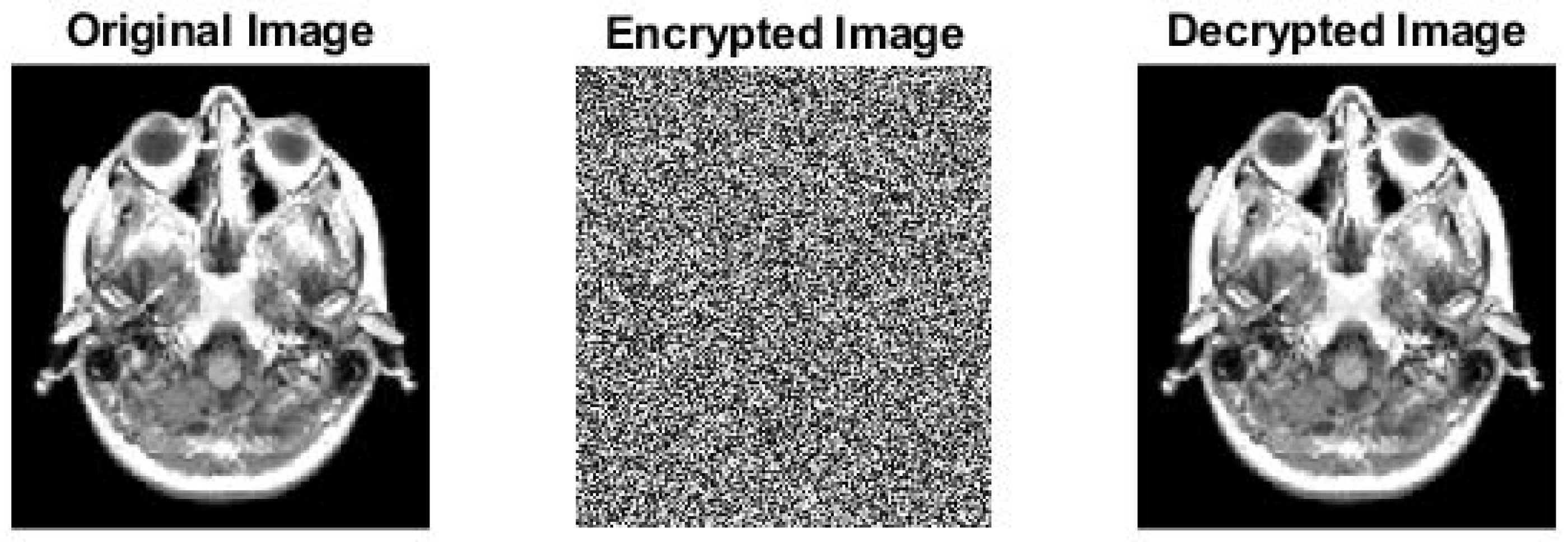

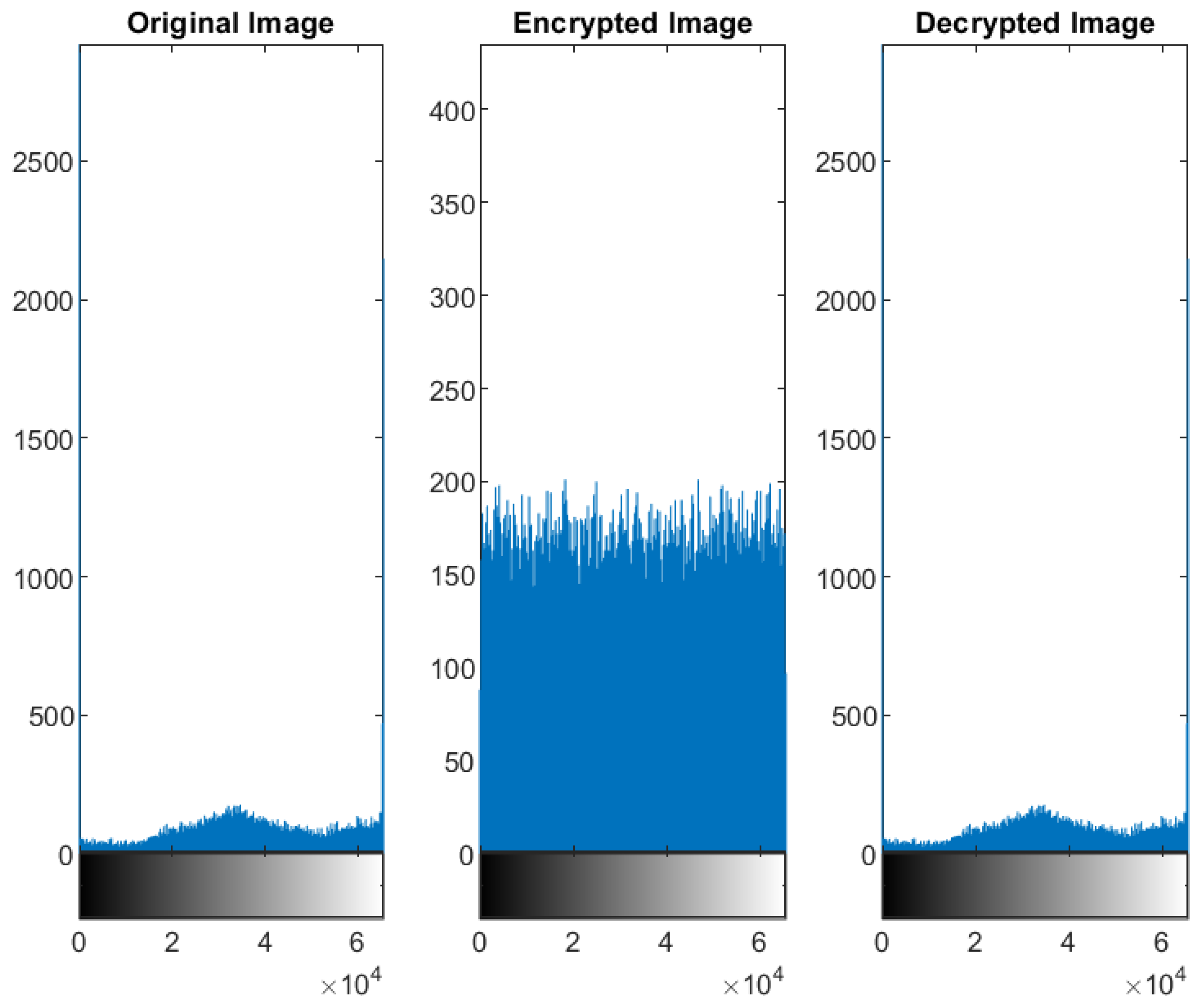

4.1. Test Image 1

4.1.1. Whole Test Image 1

4.1.2. Slice 5 of Test Image 1

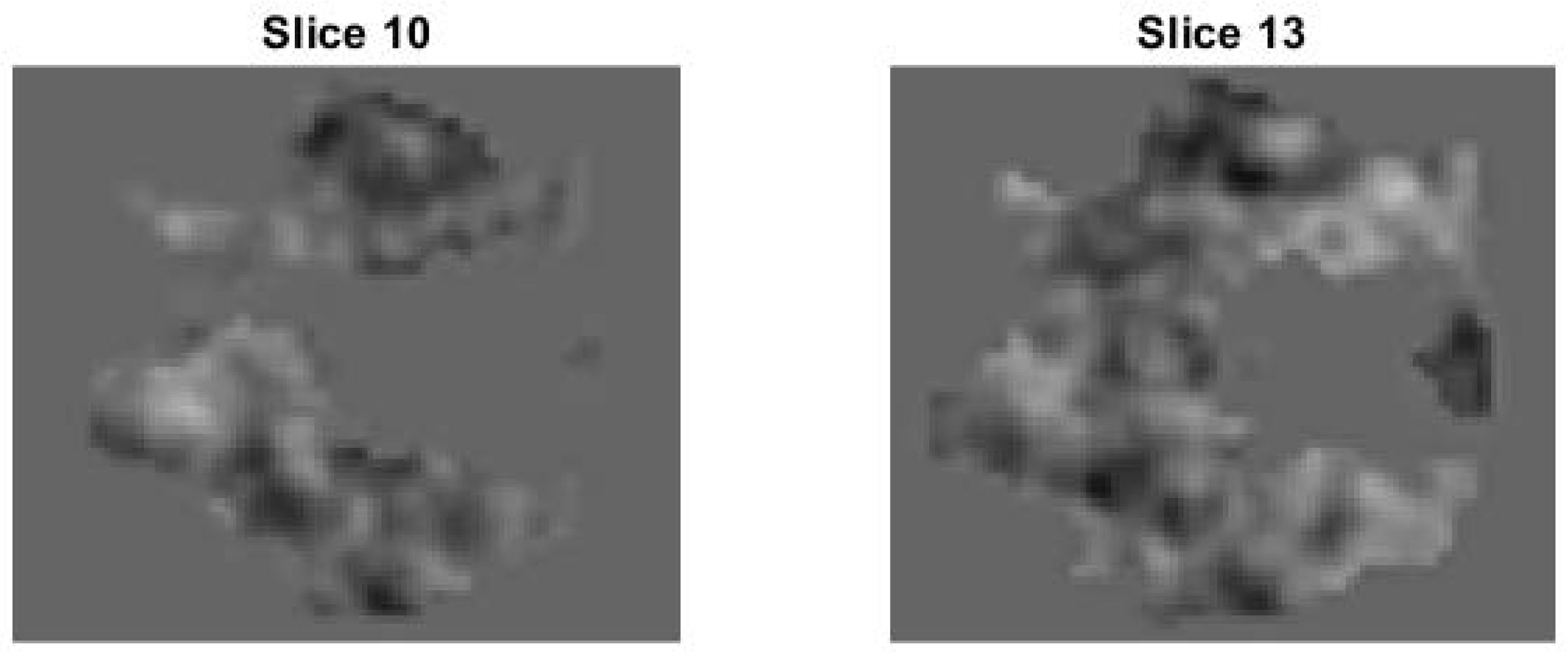

4.2. Test Image 2

4.2.1. Whole Test Image 2

4.2.2. Slice 13 of Test Image 2

4.3. Test Image 3

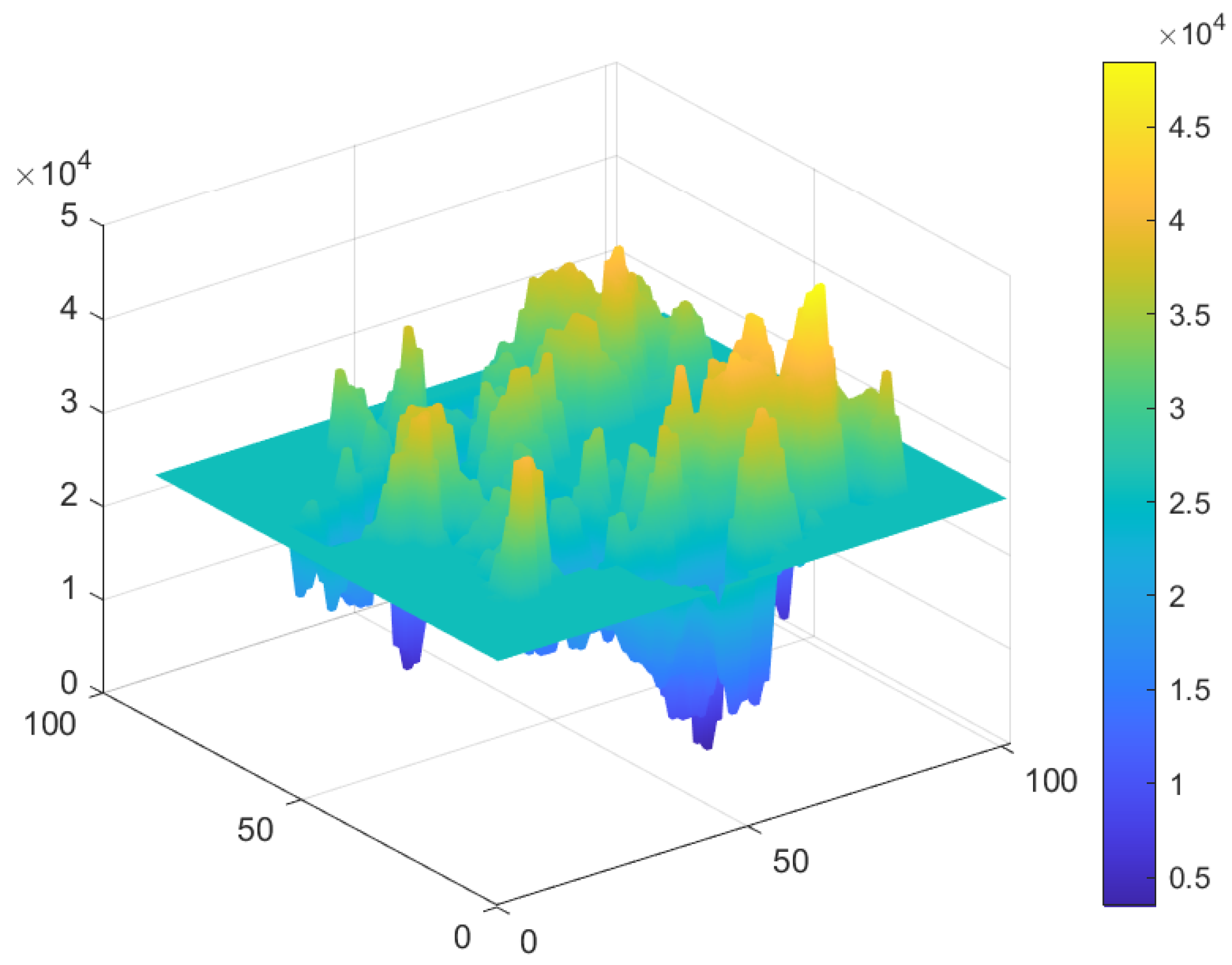

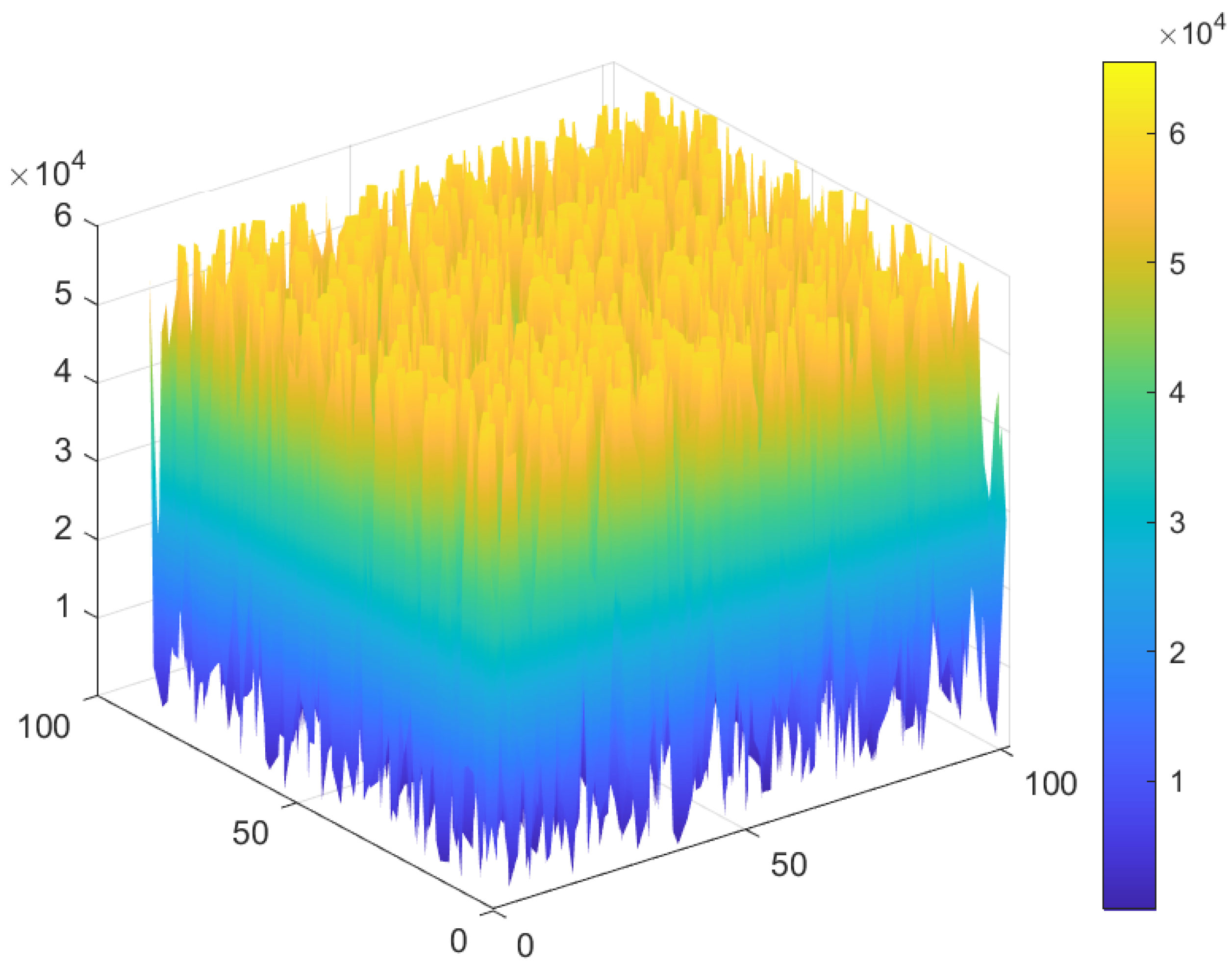

4.3.1. Preprocessing of Test Image 3

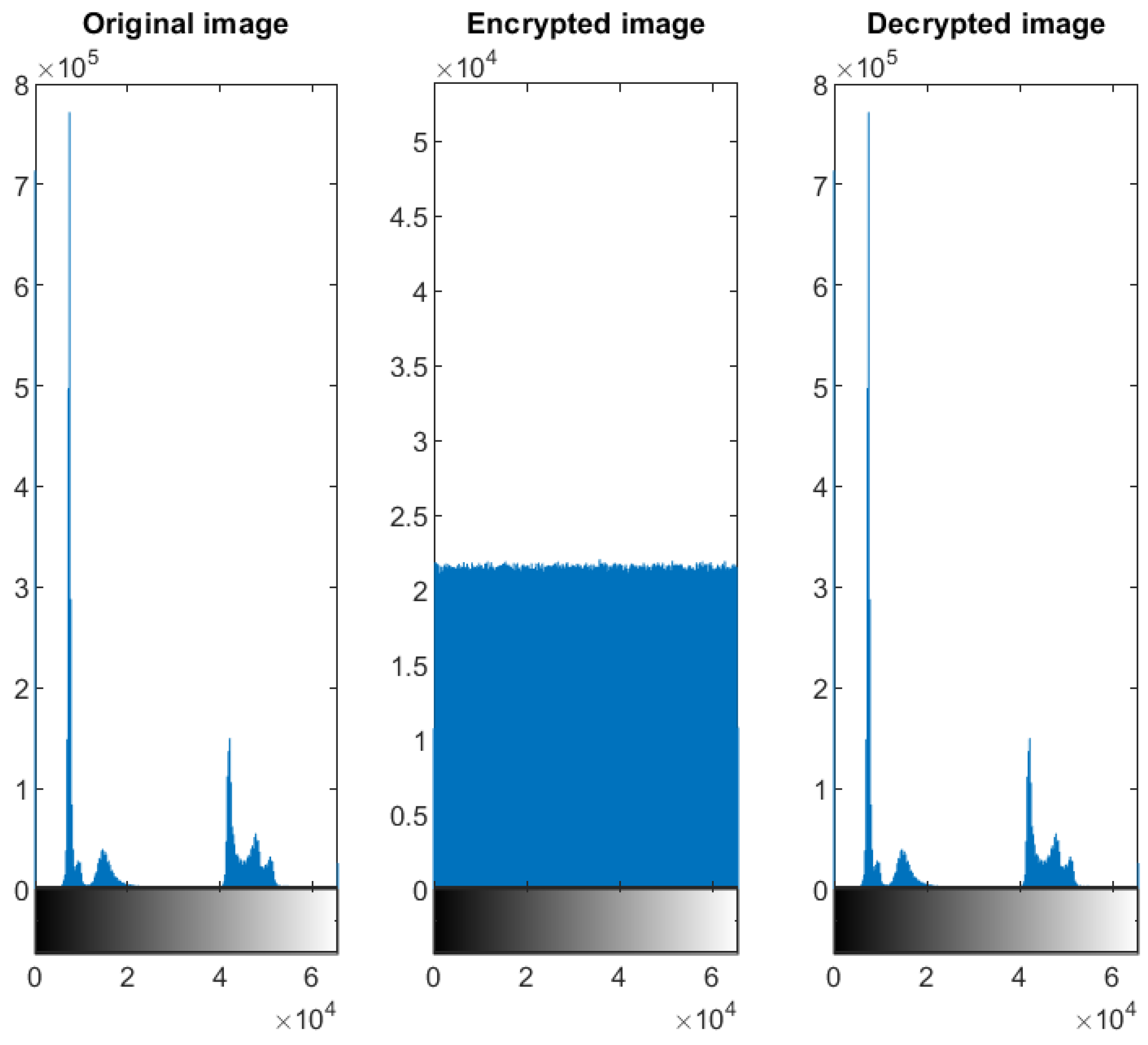

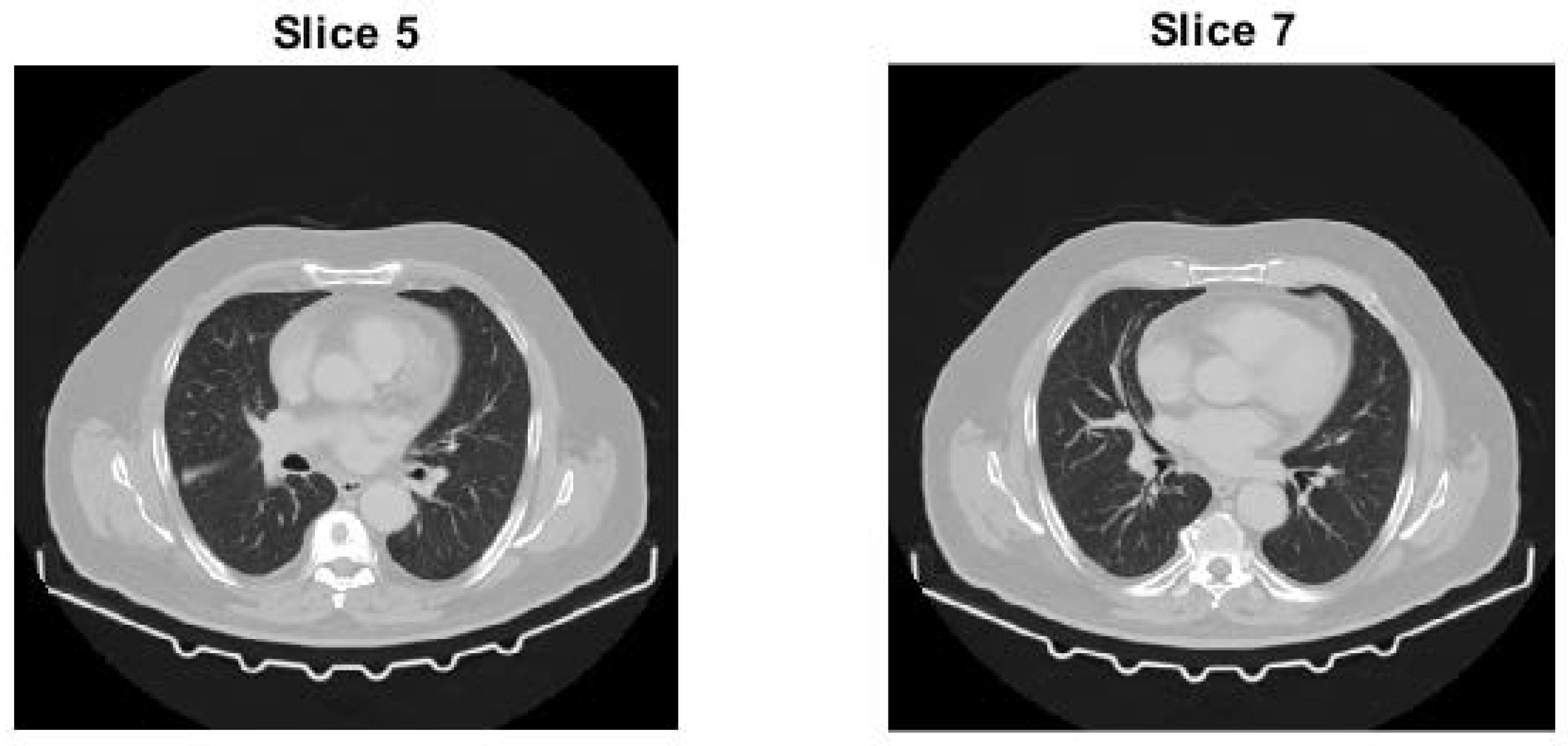

4.3.2. Whole Test Image 3

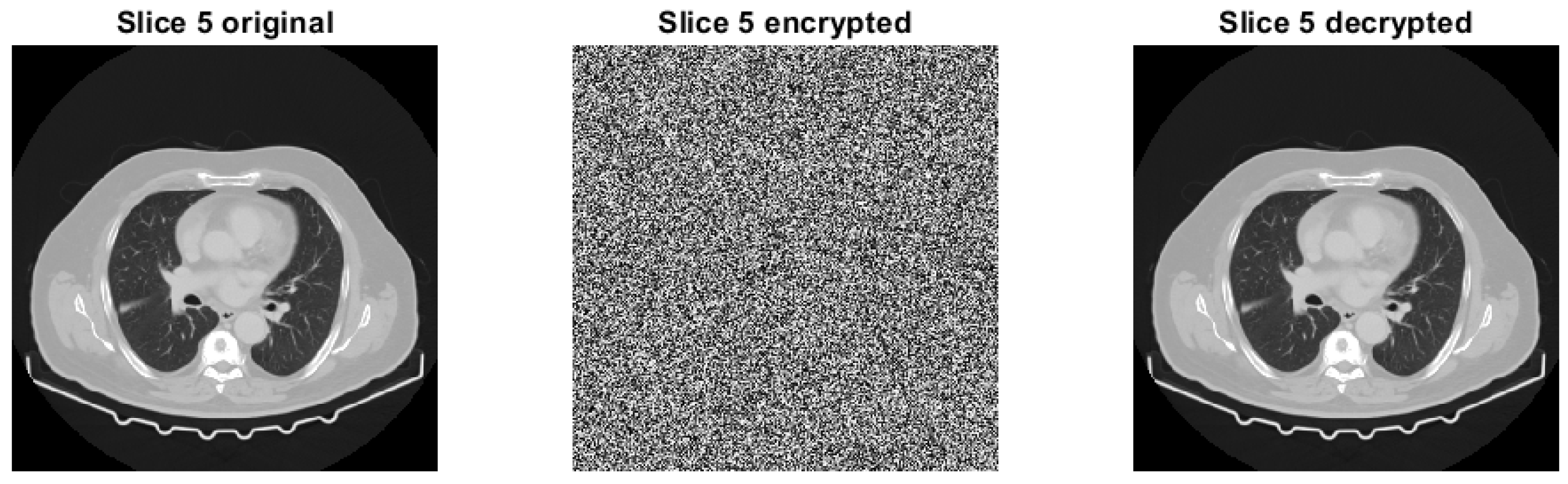

4.3.3. Test Slice of Test Image 3

5. Security Analysis

5.1. Key Space

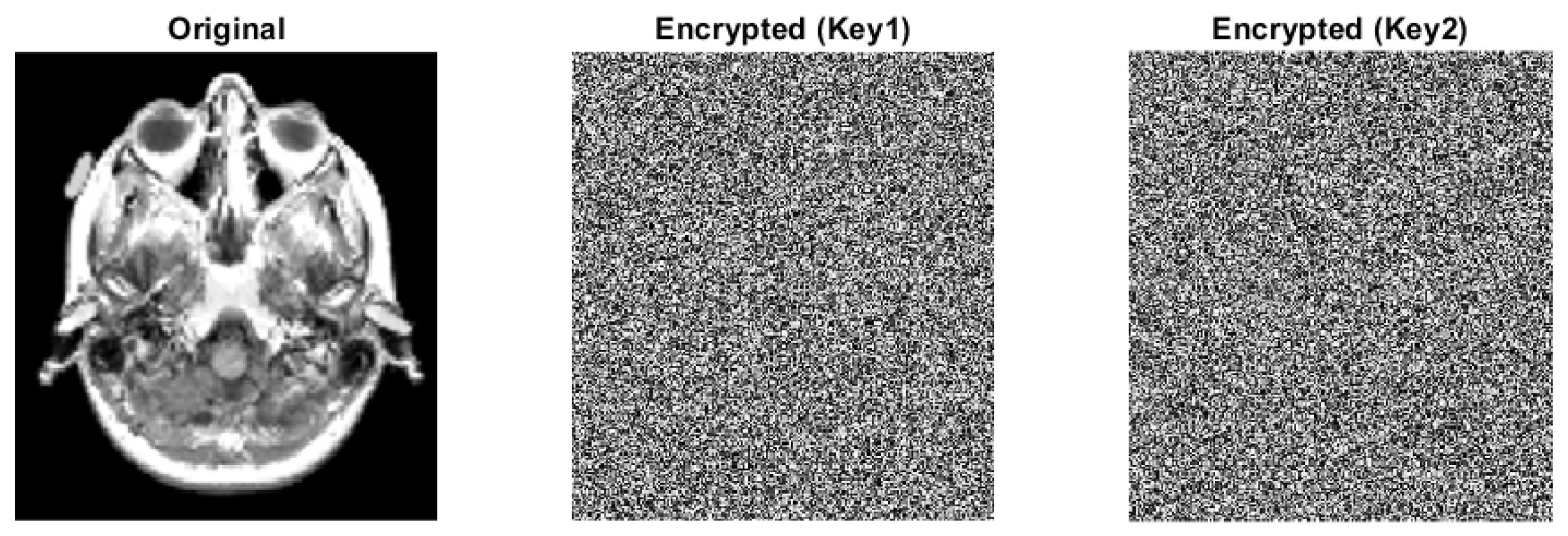

Key Sensitivity

- 1.

- Encrypt plain image with Key1 and get cipher image C1;

- 2.

- Flip one bit in Key1 to get Key2;

- 3.

- Encrypt plain image with Key2 and get cipher image C2;

- 4.

- Compute the difference between C1 and C2.

5.2. Distribution of the Encrypted Image Voxels

5.3. Information Entropy

- The richness of texture in an image;

- The effectiveness of encryption algorithms;

- The information content in an image.

- is the probability of each symbol

- H(s) is the entropy of the source s.

5.4. Plain Image Sensitivity Analysis

5.4.1. NPCR

5.4.2. UACI

- I1(x,y,z): original 3D image;

- I2(x,y,z): modified 3D image;

- Image dimensions: M × N × P;

- Max pixel value: L = 65,535. Then, the UACI for 3D 16-bit images is:

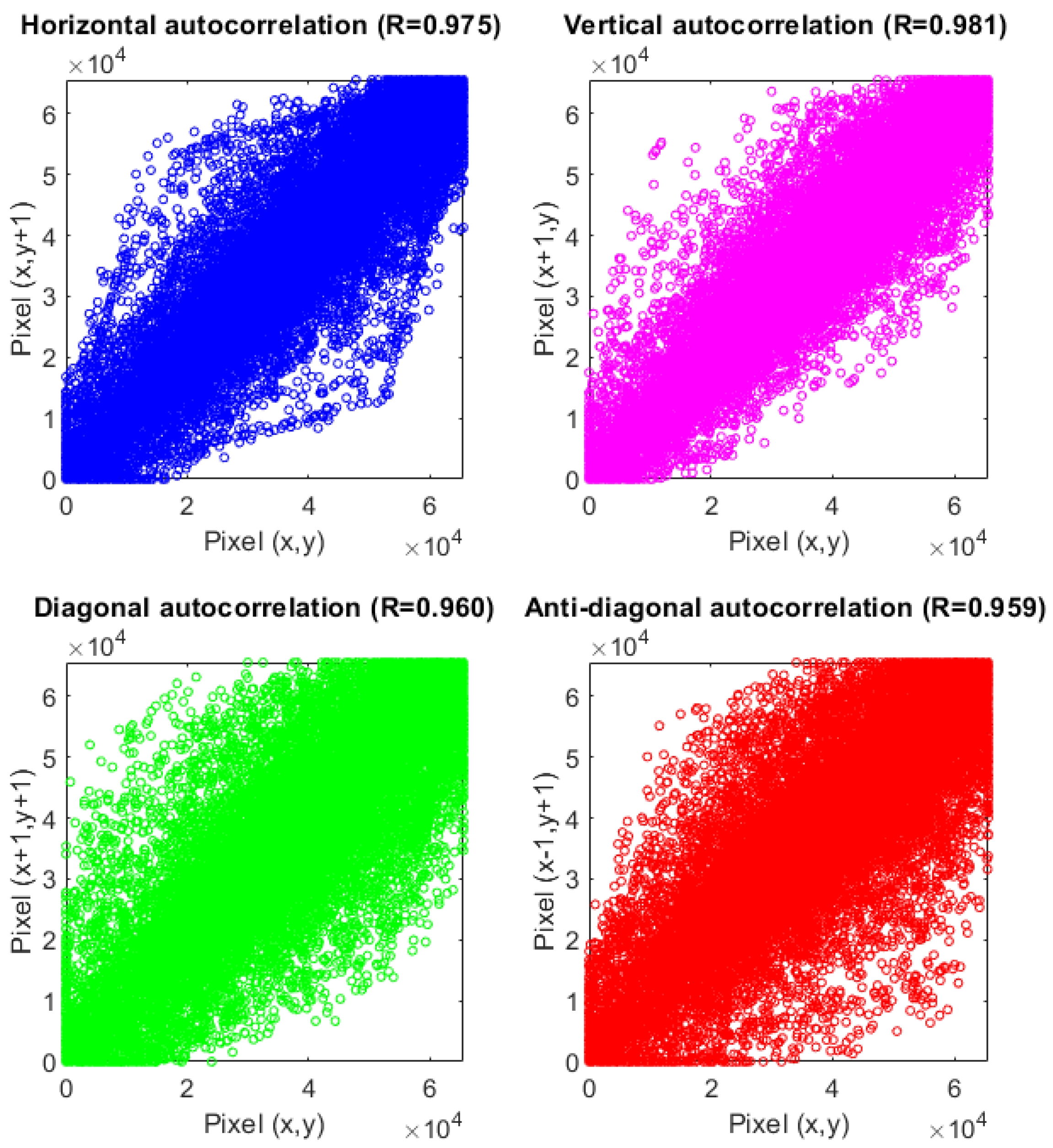

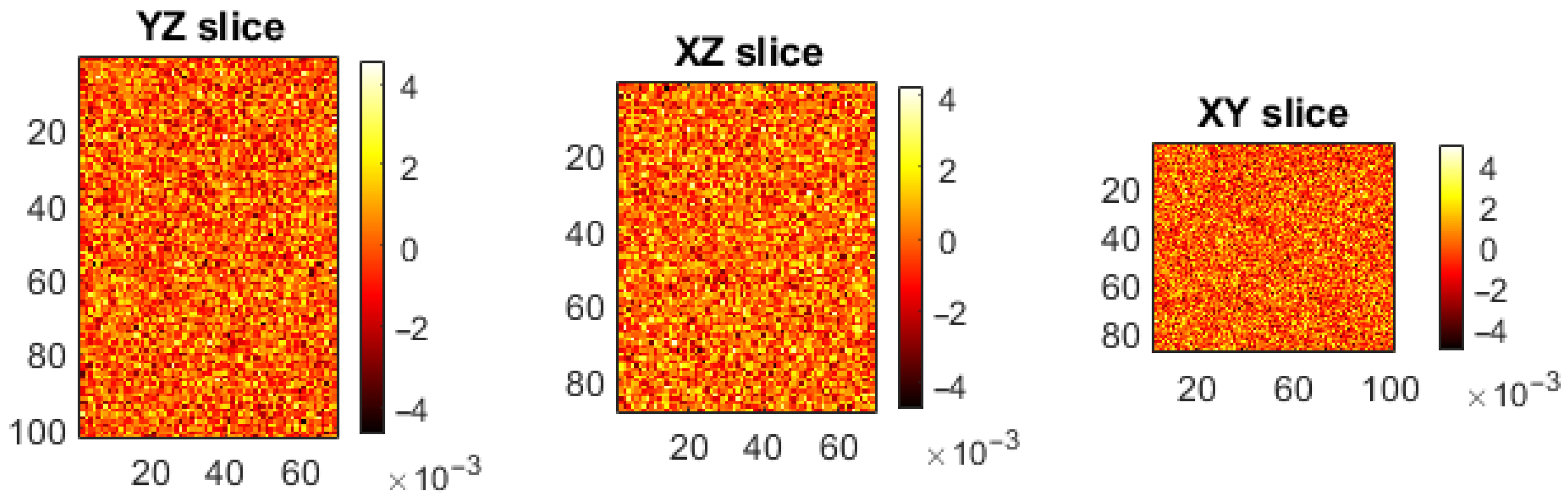

5.5. Correlation Analysis

5.6. Fourier Transformation Analysis

5.7. Difference Between Encrypted Versions of the Original

5.8. MSE and PSNR

5.9. Resistance to Chosen-Plaintext Attacks

6. Discussion

6.1. Performance Comparison

6.2. Encryption Rate

6.3. Computational Time Performance vs. Security

Without loss of security, the cryptosystem should be easy to implement with acceptable cost and speed.

6.4. Contributions and Innovations

- 1.

- It uses genetic algorithms and random walk to find optimal initial parameters for the Lorenz chaotic generator, which produce a high Lyapunov exponent.

- 2.

- It uses voxel shuffling and bit rotation transformations to increase diffusion.

- 3.

- It uses CBC encryption mode in addition to ECB encryption, for increased security.

- 4.

- It uses a 672-bit key.

- 5.

- It demonstrates superior performance in terms of entropy, key sensitivity, and resistance to various attacks.

- 6.

- It operates at high speed.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| DICOM | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NIfTI | Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| PRNG | Pseudo-Random Number Generator |

| NPCR | Number of Pixel Change Rate |

| UACI | Unified Average Change Intensity |

| ECB | Electronic CodeBook (mode) |

| CBC | Cipher Block Chaining (mode) |

| IV | Initialization Vector |

References

- Anandik, N.; Muni, S.S.; Kaushik, A. DICOM Compatible, 3D Multimodality Image Encryption using Hyperchaotic Signal. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.20689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DICOM Standard. Available online: https://www.dicomstandard.org (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Stallings, W. Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice, 8th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Elnoamy, O. Image Encryption Using the Tent Chaotic Map. Bachelor’s Thesis, The German University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt, 1 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, K.; Aji, A.; Krishnan, P. Medical Image Encryption Scheme Using Multiple Chaotic Maps. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2021, 152, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.; Alhumyani, H.; Masud, M.; Alshamrani, S.S.; Cheikhrouhou, O.; Muhammad, G.; Hossain, M.S.; Abbas, A.M. Framework for Efficient Medical Image Encryption Using Dynamic S-Boxes and Chaotic Maps. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 160433–160449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, L. Chaos-Based Image Encryption: Review, Application, and Challenges. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, G.; Li, S. Some Basic Cryptographic Requirements for Chaos-Based Cryptosystems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2006, 16, 2129–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1949, 28, 656–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, Y.; Munir, A. Image Encryption Algorithms: A Survey of Design and Evaluation Metrics. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2024, 4, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka; Singh, A.K. A Survey of Image Encryption for Healthcare Applications. Evol. Intell. 2023, 16, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Noonan, J.P.; Agaian, S. NPCR and UACI Randomness Tests for Image Encryption. Cyber J. Multidiscip. J. Sci. Technol. J. Sel. Areas Telecommun. 2011, 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Li, M.; Li, Q.; Lv, Y. Hyperchaotic Image Encryption System Based on Deep Learning LSTM. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. (IJACSA) 2023, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Zou, C. An image encryption method based on improved Lorenz chaotic system and Galois field. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 131, 535–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, M.; Sarosh, P.; Parah, S.A. Selective Medical Image Encryption Based on 3D Lorenz and Logistic System. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 45553–45574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, A.; Nordin, M.J.; Sundararajan, E. A Chaotic Cryptosystem for Images Based on Henon and Arnold Cat Map. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 536930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fu, J.; Guo, P. Image Encryption Algorithm Combining Semi-Tensor Product Compressed Sensing and Double Random-Phase Encoding. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 025118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahna, K.U. Novel Chaos Based Cryptosystem Using Four-Dimensional Hyper Chaotic Map with Efficient Permutation and Substitution Techniques; Chaos Solitons Fractals: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-M. A Novel Multi-Image Encryption Scheme Using Generalized Rectangular Transform and Advanced 5-D Hyperchaotic Map. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 43316–43337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Liu, S.; Xiao, X.; Hunag, X. Image hiding algorithm based on local binary pattern and compressive sensing. Math. Comput. Simul. 2025, 237, 316–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.T.; Hammood, D.A.; Chisab, R.F.; Al-Naji, A.; Chahl, J. Medical Image Encryption: A Comprehensive Review. Computers 2023, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, X. A Multiple-Medical-Image Encryption Method Based on SHA-256 and DNA Encoding. Entropy 2023, 25, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, S.F.; Abboud, A.J.; Radhi, H.Y. Robust Image Encryption with Scanning Technology, the El-Gamal Algorithm and Chaos Theory. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 155184–155209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, J.S.; Murali, P. A new chaotic map with large chaotic band for a secured image cryptosystem. Optik 2021, 242, 167300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Biban, G.; Chugh, R.; Tassaddiq, A.; Alharbi, R. An efficient image encryption model based on 6D hyperchaotic system and symmetric matrix for color and gray images. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Nassan, W.; Bonny, T.; Al-Shabi, M.A. Chaos-Based Encryption System of DICOM Medical Images. In Proceedings of the Multimodal Image Exploitation and Learning 2024, National Harbor, MD, USA, 21–26 April 2024; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; Volume 13033, pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhasini, P.; Kanchana, S. Enhanced Fractional Order Lorenz System for Medical Image Encryption in Cloud-Based Healthcare Administration. Int. J. Comput. Netw. Appl. 2022, 9, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belazi, A.; Talha, M.; Kharbech, S.; Xiang, W. Novel Medical Image Encryption Scheme Based on Chaos and DNA Encoding. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 36667–36681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, J.S.; Murali, P. A novel DICOM image encryption with JSMP map. Optik 2022, 251, 168416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortajez, S.; Tahmasbi, M.; Zarei, J.; Jamshidnezhad, A. A novel chaotic encryption scheme based on efficient secret keys and confusion technique for confidential of DICOM images. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2020, 20, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, T. Medical image encryption algorithm based on a new five-dimensional multi-band multi-wing chaotic system and QR decomposition. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhang, F.; Huang, T.; Lu, M. Medical Image Encryption Based on Josephus Scrambling and Dynamic Cross-Diffusion for Patient Privacy Security. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 9250–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, R. 3D Medical Image Encryption Algorithm Using Biometric Key and Cubic S-box. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 055035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zou, C. An Encryption Algorithm for Multiple Medical Images Based on a Novel Chaotic System and an Odd-Even Separation Strategy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-El-Atty, B.; El-Affendi, M.A.; Chelloug, S.A.; Abd El-Latif, A.A. Double Medical Image Cryptosystem Based on Quantum Walk. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 69164–69176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.S.; Madeiro, F.; Lima, J.B. Encryption of 3D Medical Images Based on a Novel Multiparameter Cosine Number Transform. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 121, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yan, W.; Chi, Z. A new image encryption algorithm based on optimized Lorenz chaotic system. Concurrency Comput. Pract. Exp. 2020, 34, e5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, L. Breaking a Chaotic Encryption Based on Hénon Map. In Proceedings of the 2010 Third International Symposium on Information Processing (ISIP), Qingdao, China, 15–17 October 2010; pp. 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, G.; Montoya, F.; Romera, M.; Pastor, G. Cryptanalyzing a Discrete-Time Chaos Synchronization Secure Communication System. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2004, 21, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhang, C.; Lu, H.; Li, M.; Liu, Y. Cryptanalysis of a New Chaotic Image Encryption Technique Based on Multiple Discrete Dynamical Maps. Entropy 2021, 23, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.K. Numerical Approximation of Lyapunov Exponents and its Applications in Control Systems. Master’s Theses, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, USA,, 2021. Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/2278 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Blesa, A.; Serón, F.J. Advancement of the DRPE Encryption Algorithm for Phase CGHs by Random Pixel Shuffling. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What is p-Box in Cryptography? Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/computer-networks/what-is-p-box-in-cryptography/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Tutorials Point. Cryptography—ChaCha20 Encryption Algorithm. Available online: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/cryptography/cryptography_chacha20_encryption_algorithm.htm (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Network Encyclopedia. ChaCha20: The Dance of Cryptography. Available online: https://networkencyclopedia.com/chacha20-the-dance-of-cryptography (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Crypto Done Right. AES CTR Mode. Available online: https://cryptodoneright.org/articles/symmetric_algorithms/mode_ctr/aes_ctr_dev_quickstart (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Buchanan, W. CTR Mode in AES. 11 January 2025. Available online: https://asecuritysite.com/blog/2025-01-11_CTR-Mode-in-AES-1e3db1c74716.html (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Li, C.; Luo, G.; Li, C. An Image Encryption Scheme Based on the Three-dimensional Chaotic Logistic Map. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2019, 21, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. An Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Improved Hilbert Curve Scrambling and Dynamic DNA Coding. Entropy 2023, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaopeng, W.; Ling, G.; Qiang, Z.; Jianxin, Z.; Shiguo, L. A novel color image encryption algorithm based on DNA sequence operation and hyper-chaotic system. J. Syst. Softw. 2012, 85, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Medical Images | Common Images |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Diagnosis, treatment | Documentation, communication, art |

| Acquisition | X-ray, MRI, CT, Ultrasound, etc. | Cameras (visible light) |

| Color/Grayscale | Mostly grayscale, some color | Mostly full-color |

| Bit Depth | High (12–16 bits) | Lower (8 bits per channel) |

| Format | DICOM | JPEG, PNG, HEIC |

| Dimensionality | 2D, 3D, or 4D | Mostly 2D |

| Metadata | Extensive (patient, device, settings) | Limited (EXIF) |

| Interpretation | Requires medical expertise | Intuitive for general public |

| Quantitative Use | Yes (measurable pixel values) | No (perceptual only) |

| Image | Entropy Original 1 | Entropy Encrypted 1 | NPCR | UACI 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Image 1 | 10.0388 | 15.9801 | 99.9989% | 33.34–33.47% |

| Test Image 2 | 10.2576 | 15.9233 | 99.9987% | 33.37–33.47% |

| Test Image 3 | 8.0448 | 15.9914 | 99.9986% | 33.34–33.47% |

| Image | Dimension | Original | Encrypted |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | 0.9807 | −0.0003 | |

| Test Image 1 | Y | 0.9579 | 0.0000 |

| Z | 0.9706 | 0.0002 | |

| X | 0.9379 | −0.0009 | |

| Test Image 2 | Y | 0.9468 | 0.0007 |

| Z | 0.9295 | 0.0030 | |

| X | 0.9848 | 0.0003 | |

| Test Image 3 | Y | 0.9890 | −0.0005 |

| Z | 0.9308 | 0.0002 |

| Image | MSE | PSNR |

|---|---|---|

| Test image 1 | 972166690.80 | 6.46 dB |

| Test image 2 | 424839310.33 | 10.05 dB |

| Test image 3 | 845014081.06 | 7.06 dB |

| Metrics | Proposed | Ref. [29] | Ref. [1] | Ref. [36] | Ref. [15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 3D | 2D | 3D | 3D | 2D |

| Image Formats | uint8, uint16, NIfTI, DICOM | uint8, uint16, DICOM | uint16 | - 1 | - |

| Entropy (norm.) | 0.9978 | 0.99997 | 0.9988 | 0.99948 | 0.99986 |

| NPCR avg (%) | 99.9988 | 99.9994 | 99.9978 | 99.73 | 99.655 |

| UACI avg (%) | 33.38 | 33.69 | 33.34 | 33.64 | 33.53 |

| Corr. X avg | 0.0005 | 0.001132 | 0.00036 | - | 0.0151 |

| Corr. Y avg | 0.0004 | −0.001974 | 0.00049 | - | 0.0267 |

| Corr. Z avg 2 | 0.0011 | 0.001252 | 0.00044 | - | 0.0278 |

| PSNR | 7.857 | 26.6476 | - | 6.8125 | 9.7262 |

| Key length | 672 | 233 | 1344 | - | 359 |

| Scheme | Platform (Software & Hardware) | Throughput (MB/s) |

|---|---|---|

| [4] | Mathematica / 2.6 GHz Intel Core i7, 16 GB RAM | 0.083 |

| [35] | MATLAB R2016b / Intel Core2Duo @ 3.00 GHz, 4GB RAM | 7.5429 |

| [5] | Not specified / Not specified | 0.4369 |

| [48] | MATLAB 2014b / Intel Core2Duo @ 2.26 GHz, 4GB RAM | 3.8245 |

| Proposed | MATLAB R2019b/ Core i5 @ 1 GHz, 8 GB RAM | 6.8255 |

| Proposed | MATLAB R2021a/ AMD Ryzen 9 @ 4 GHz, 16 GB RAM | 12.0441 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andreatos, A.S.; Leros, A.P. Secure Chaotic Cryptosystem for 3D Medical Images. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203310

Andreatos AS, Leros AP. Secure Chaotic Cryptosystem for 3D Medical Images. Mathematics. 2025; 13(20):3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203310

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndreatos, Antonios S., and Apostolos P. Leros. 2025. "Secure Chaotic Cryptosystem for 3D Medical Images" Mathematics 13, no. 20: 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203310

APA StyleAndreatos, A. S., & Leros, A. P. (2025). Secure Chaotic Cryptosystem for 3D Medical Images. Mathematics, 13(20), 3310. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13203310