Abstract

This study aims to evaluate the sustainability performance of EU regions through a comprehensive and data-driven Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) framework, addressing the increasing demand for regional-level analysis in sustainable finance and policy design. Leveraging Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression and cluster analysis, we construct composite ESG indicators that adjust for economic size using GDP normalization and LOESS smoothing. Drawing on panel data from 2010 to 2023 and over 170 indicators, we model the determinants of ESG performance at both the national and regional levels across the EU-27. Time-based ESG trajectories are assessed using Compound Annual Growth Rates (CAGR), capturing resilience to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical instability. Our findings reveal clear spatial disparities in ESG performance, highlighting the structural gaps in governance, environmental quality, and social cohesion. The model captures patterns of convergence and divergence across EU regions and identifies common drivers influencing sustainability outcomes. This paper introduces an integrated framework that combines PLS regression, clustering, and time-based trend analysis to assess ESG performance at the subnational level. The originality of this study lies in its multi-layered approach, offering a replicable and scalable model for evaluating sustainability with direct implications for green finance, policy prioritization, and regional development. This study contributes to the literature by applying advanced data-driven techniques to assess ESG dynamics in complex economic systems.

Keywords:

ESG modeling; partial least squares regression; sustainable economic systems; panel data analysis; regional sustainability; econometric modeling MSC:

62Hxx; 62Pxx; 62Jxx; 03Cxx

1. Introduction

The Member States of the European Union have intensified their efforts to enhance economic performance by launching a series of reforms and policy initiatives aimed at improving public sector efficiency and fostering innovation [1]. In the context of accelerated social and digital transformations, the European Union is under increasing pressure to adapt and respond to multiple challenges, including institutional inefficiency, disruptive digitalization, declining social well-being, and public health concerns [2].

This paper highlights the importance of developing accurate performance measurement indicators and strong empirical evidence to refine policies and strategies at the level of European Union countries and regions. The complexity of these challenges, amplified by the global COVID-19 pandemic and economic uncertainties, requires advanced methodological approaches to capture the multidimensional nature of performance.

While various qualitative and bibliometric approaches have supported the strategic framing of ESG policies in the past, this paper takes a distinct empirical direction by relying primarily on structured regional-level panel data and applying econometric and clustering techniques to identify performance patterns.

This research highlights the potential of comprehensive assessments and the application of innovative econometric models, such as Partial Least Squares (PLS), to assess the efficiency and sustainability of regional development within the European Union. However, the systematic use of such methods at the regional level remains limited, and their capacity to inform policy interventions requires further development.

Therefore, the present study proposes a data-driven, quantitative analysis of ESG performance using a multidimensional methodological framework, focusing on observable indicators at the NUTS-2 regional level across the EU. This paper aims to bridge these gaps by using a holistic approach to assess economic performance and sustainability in European Union countries. Specifically, this includes a combination of PLS regression (to identify latent relationships among ESG indicators), LOESS-based GDP deflation (to normalize economic outputs over time), and hierarchical cluster analysis (to classify EU regions based on performance similarities). The data used in this research consists of over 10 years of structured panel datasets (2010–2023), covering 27 EU countries, with indicators selected from Eurostat, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

This approach allows us to systematically explore and identify performance trends, contributing to the literature with new methodological perspectives and empirical evidence on the performance of European Union countries and regions.

Further, this paper addresses a research gap in the literature by applying ESG analysis at the subnational (regional) level. To date, ESG analysis has been studied at the firm and national levels, but few studies have examined regional ESG performance among EU Member States [3,4,5]. These studies highlight the significance of institutional quality, social capital, and spatial development as determinants of regional sustainability performance.

Additionally, our proposed approach builds on composite indices such as the OECD Regional Well-Being Index [6], which, while widely used for descriptive purposes, also relies on additive aggregation and equal-weighting schemes. However, such methods have not sufficiently addressed issues of non-linearity and multicollinearity or considered temporal differences and trends. In contrast, LOESS deflation for GDP and PLS regressions used in this paper allow for the dynamic normalization of economic indicators and multidimensional sustainability outcomes marked with enhanced statistical rigor.

The general research question guiding this study is: “How can the performance of European Union countries on various dimensions, including governance, social and economic aspects, be accurately measured and analyzed using a new methodological framework?”. Using an innovative methodological approach encompassing PLS econometric modelling and cluster analysis, this study aims to develop a global understanding of performance dynamics in EU regions. This research explores (i) which ESG pillars contribute most to regional convergence or divergence across the EU, (ii) how ESG performance has evolved over time in response to external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iii) what structural characteristics define clusters of countries that follow similar ESG trajectories.

In line with these questions, we formulate and test the following hypotheses:

H1.

Governance is the strongest driver of composite ESG performance in the EU Member States.

H2.

Northern and Western European countries exhibit greater ESG convergence due to institutional robustness and policy alignment.

H3.

The environmental pillar shows the greatest spatial divergence due to unequal enforcement capacity and ecological exposure.

These hypotheses are tested using a multidimensional methodological framework that integrates PLS regression, LOESS-based GDP-deflation, and hierarchical cluster analysis. This methodology allows for a robust investigation of the key drivers, trends, and disparities in regional ESG sustainability performance across the EU.

Over the past two decades, ESG considerations have become integral to assessing sustainability performance across both public and private sectors. Rather than offering a general definition, this study focuses on how ESG metrics can be operationalized to capture regional disparities, track long-term progress, and inform investment and policy decisions at the EU level [7].

Despite the expansion of ESG frameworks, one persistent challenge is the inconsistency and divergence of ESG scoring systems provided by various rating agencies. Dumrose’s paper analyzes the European Union’s taxonomy in the context of ESG scores. Firm-level ESG scores tend to differ between ESG data providers, influencing investment decisions due to uncertainty about a firm’s sustainability performance. The European Union taxonomy can support the reduction of this divergence [8].

The results highlight a positive and significant relationship between E ratings and firm-level taxonomy performance. Thus, investment and political decision-makers can be established, i.e., investors could anticipate the potential implications of the taxonomy on their investments, such as changes in the cost of capital or capital reallocations by other investors [8]. Policymakers can build on our findings to develop effective regulations for sustainable finance and improve quality.

Several empirical studies have investigated the correlation between ESG scores and firm profitability. For example, ref. [9] conducted a study on the European tourism sector and identified a statistically significant negative correlation between ESG scores and return on assets. This research specifically aimed to investigate the existence of a significant relationship between ESG scores and firms’ profitability, defined by return on assets, and whether there is a positive, negative, or neutral relationship between them.

Based on the regression model applied, the results highlighted a negative relationship between ESG scores and firm performance, as described by return on assets, which is statistically significant for a materiality threshold of 5%. They suggest that firms must implement effective and appropriate practices that take into account ESG score information. Moreover, companies should promote the long-term benefits they derive from applying these practices and comply with their standards.

In contrast, ref. [10] applied machine learning models to assess ESG scores within EuroStoxx-600 companies, finding a positive relationship between ESG performance and EBIT, especially post-2018, following EU sustainability reforms. He investigated the relationship between ESG scores and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) and assessed the extent to which ESG scores significantly influence companies’ profitability using machine learning methods. After the European Commission implemented a sustainable growth program in 2018, ESG scores began to rise. Thus, it was of interest to determine what happened in the two years of analysis.

The machine learning algorithms utilized indicated a score greater than 75 for the data from 2020, which is indicative of an increase in EBIT value when ESG scores are increased. A similar behavior was observed within regions where ESG scores for the entire dataset were in the range of 50–75. Therefore, to have any increase in EBIT value, it suggests that the firm will need to have strong, sustainable investments. Indeed, ESG scores have been shown to impact the profitability of firms, as represented by companies’ EBIT. In contrast, for a low ESG score, we can assume that the firm will be less focused on the objective of sustainability and the sustained use of sustainability. It does not add an additional profit margin. These complex or contradictory findings speak to the contextuality of the correlation found in ESG financial performance, but the implications of sector and geographic conditions need to be differentiated and applied in ESG modeling. These studies increase our ability to understand the implications of ESG impact at the micro level but lack application to regional policy and development plans. The transition from a firm-level to a regional level will need to rely on stronger, more sophisticated frameworks to reflect multivariate, spatially variable behavior more clearly. Further, ESG conditions have also been shown to influence systemic financial stability. Research by [11,12] shows that institutions with strong ESG performance are less likely to experience financial distress, especially during constraints like those attached to the global financial crisis and the recent COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, environmental performance appears to positively influence economic profitability and market performance; the governance pillar is observed to negatively affect financial and operational performance [11]. In a complementary study, ref. [12] tested five hypotheses connecting ESG quality to banking stability and found that social and fairness can help mitigate financial risk, especially during constraints like those during the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies demonstrate how ESG can be used as a predictive and diagnostic measure of institutional resilience. By extension, for example, at the regional level, ESG can act as a predictive early warning system for vulnerabilities in public administration, health services, and social infrastructure. Ref. [12]’s conclusions can have clearer implications for EU cohesion policy and perhaps ease the measuring of regional convergence and resilience. Furthermore, by applying ESG elements to fiscal and social risk indicators and spatial risk models using appropriate econometric methods (many of which are well suited to ESG, as in the case of PLS regression, as proven by authors like [13,14], researchers can quantify these variables in a robust manner, thereby enhancing the evaluative capacity of regional planning tools and aligning social sustainability performance measurement with long-term EU objectives for development and resilience. While conventional econometric models often dominate this type of research, PLS and similar approaches have recently emerged as viable techniques to organize complex high-dimensional data, mitigated by low sample sizes and inherent collinearity, which is often present in ESG material and data. PLS, as undertaken by [13,14], uses latent variables to help researchers feasibly analyze and work with data according to the two stated recognizable characteristics of ESG data. The relationship between corporate strategy, ESG performance, and bankruptcy risk in U.S. firms was studied from 2016 to 2020 using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [14]. The authors find that successful cost management strategies are positively associated with ESG scores and lower probabilities of financial distress. Furthermore, ESG and financial performance acted as mediating variables between corporate strategy and bankruptcy likelihood, reinforcing the importance of long-term corporate strategizing. The authors also provide evidence that financial performance plays an important role in mitigating the risk of insolvency. The authors argue that firms and new policies should prioritize the continuous evaluation of ESG and need supportive regulatory environments that support this approach [14]. Relatedly, ref. [13] captures how ESG factors affect firm-level risks in Europe. The authors distinguish between systematic, idiosyncratic, and total risks and use regression and causality analyses to account for the differential effects of each ESG pillar. The effects of ESG performance are statistically significant, reflecting that all three types of risks are lower as ESG scores are higher, with the social aspect having the greatest protective effect against risk. Idiosyncratic risk was reduced with better environmental performance; however, total and systematic risks were higher for green industries. Corporate governance was not directly related to firm value; however, a bidirectional relationship existed between corporate governance and systematic risk. All the findings support the idea that ESG practices could be better incorporated by businesses and would contribute to decreasing risky activity and increasing resilience, driven strongly by socially oriented performance. However, despite the advantages described, PLS can be underutilized in regional studies. Most existing applications are oriented toward corporate purposes and do not use the full potential of the method in the field of public policy evaluation or regional diagnostics. In this paper, themethodology is applied with the mindset of public policy evaluation since the European Union engages in evidence-based policymaking and systemic evaluation under frameworks such as the Green Deal or NextGenerationEU. At the sovereign level, refs. [15,16] identify a negative relationship between a country’s ESG performance and its sovereign bond spreads across all components, especially governance and social components. The evidence suggests a credibility premium for sustainability-oriented countries in the international capital market. Although national governments serve as the focus of the studies noted above, the findings provide evidence to support the economic rationale for taking the next step into the subnational level. Whereas [17] found both ESG disclosure and actual ESG performance to have positive impacts on the borrowing costs of non-financial firms in the EU, the distinction between ESG disclosure and actual ESG performance remains an important one, particularly at the regional scale, where the quality and transparency of ESG indicators vary considerably. The dilemma inherent in ESG ratings as lax rating standards allow those subject to ESG ratings to manipulate ratings, leading to calls for a more systematic approach to theory paradigms, recognizing that they do not distinguish between more conservative or more progressive rating systems, nor necessarily the complexities of the sustainability concept [18]. This problem has been addressed directly in this study by introducing rigor into the methodology and normalizing indicators. Among the earliest attempts to examine sustainability at the macroeconomic level using ESG metrics, ref. [15] examined the influence of government ESG performance on sovereign bond markets. Using a panel-level regression model, this study tests the hypothesis that higher ESG ratings are related to lower borrowing costs. They found that there was a relationship, but the effect of ESG ratings was much weaker—about a third of the effect of traditional financial ratings from S&P. Thus, while investors are increasingly using ESG factors as a source of value relevant to their risk assessment, ESG factors are not a substitute for financial metrics when assessing sovereign debt. Extending this study in [10], measured the differential impact of environmental, social, and governance components on sovereign bond spreads. A panel regression model was constructed, and it was found that a 10% increase in the composite ESG was, in turn, correlated with a 15% reduction in sovereign spreads. The governance and social dimensions of ESG have statistically significant impacts on spreads, without any conclusive impact of the environmental dimension. In this way, although the findings of their analysis are limited by measurement concerns and data availability, the synthesis of ESG performance, especially governance, is important for understanding these variables to strategically assess sovereign risk and allocate capital. While these studies provide valuable insights, very few have applied ESG modeling at the subnational level, especially within the European Union context. The biggest issue with existing research is that it tends to suffer from fragmentation in methodology and/or limited scope, focusing primarily on the non-linear and multidimensional aspects of regional sustainability. Based on the EU’s aggressive objectives and aspirations outlined in the European Green Deal and the 2021–2027 Cohesion policy, there is a genuine need to have a more nuanced, data-driven, and methodical footprint. This study aims to respond to that need by applying PLS regression and cluster analysis on over 10 years of regional panel data, so that we can hopefully offer a replicable model for capturing the variation of ESG performance differences across EU regions that could be supportive for policy evaluation that aligns to the EU’s long-term objective of achieving resilient, sustainable, and inclusive territorial development. The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents the materials and methods, including the data sources, selected indicators, and econometric techniques utilized. Section 3 presents the empirical results regarding the patterns of ESG performance and their determinants across EU countries. Section 4 discusses the results with respect to the existing literature and their implications for policy. Finally, Section 5 outlines the key conclusions and possible implications for future research and sustainable regional development strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

This section highlights the methodological steps taken to build and conduct ESG performance scores across European Union Member States from 2010 to 2023. The methodological approach uses a series of statistical methods to address data quality issues, standardize measures, and create usable cross-country comparisons. After a preparatory step in data organization, treatment of missing data points and outliers, and smoothing and normalizing to account for typical economic differences, composite scores for each ESG pillar are developed using PLS regression, which is appropriate for research based on many correlated indicators. The ESG performance scores are then analyzed to measure changes in performance over time via annual growth rates calculated using the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR). Cluster analysis is then used to group countries with identifiable similarities in ESG performance.

The analysis is based on a dataset developed around the three pillars of ESG performance: Environmental, Social, and Governance. The measures were selected from indicators provided by Eurostat, the World Bank, and the WHO for the years 2010 to 2023. These sources were selected because they offer internationally comparable and methodologically consistent datasets that are widely used in academic and policy research [19,20,21]. In total, 178 measures were selected-50 measures corresponding to environmental performance outcomes, 102 measures reflecting indicators of social performance, and 26 measures related to governance performance. This equates to 2492 observations of the member countries of the European Union. The variable names and sources are listed in Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3.

The selection of indicators followed a screening process to ensure conceptual coherence. First, a broad review of all ESG-related indicators available through Eurostat, the World Bank and WHO was conducted. Second, the indicators were retained based on three main criteria: (1) relevance to ESG performance as defined by established frameworks like the EU Taxonomy Regulation [22], Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation [23], and the World Bank ESG Data Portal [24]; (2) sufficient data availability across EU Member States over the period 2010–2023; and (3) cross-country comparability through methodological consistency. Preference was given to outcome-based indicators rather than inputs or intentions so that the realized ESG performance would be better reflected.

A major limitation is data availability, especially for the dimension of governance at the sub-national level. Institutional arrangements, structures, and governance processes are sometimes not regularly reported, limiting research quality and resulting in far fewer indicators for that dimension. Regional-level data are also sparse and, therefore, noncomparable because of inconsistent reporting by Member States. To manage this discontinuity in indicators at the regional level, national-level data analysis was first performed, subsequently subjecting the indicator to a regionalization procedure based on GDP per capita, which provided an approximation of subnational ESG performance.

The final estimations of the indicators excluded the United Kingdom. While the time period includes times during which the UK was a member of the EU, we have omitted it to achieve greater consistency when interpreting trends and avoid inferred distortions to comparative scores.

Due to the significant disparity in economic size across EU countries, all values for GDP per capita were log-transformed to improve the statistical properties of the data and allow comparability across countries and years.

Missing data were handled using a multi-step imputation process. The first step was to assess each time series for missing data across all 178 indicators and the 27 EU Member States. If a missing observation occurred at the beginning or the end of a time series, the gap was filled using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) or first observation carried backward (FOCB), respectively. This approach ensured temporal continuity when the missing data were boundary values. However, when the missing values fell between two valid observations, the series was completed using linear interpolation, estimating the annual growth rate based on the two closest valid points and inferring the intermediate values. For years after 2021, in the absence of new data, we assumed that the last known growth rate would hold and extrapolated forward. In cases where gaps could not be filled by interpolation or extrapolation, the missing values were median-imputed. This ensured the preservation of the distributional characteristics. These procedures were uniformly applied across all indicators to maintain cross-country comparability and temporal consistency.

While more advanced methods, such as multiple imputation or model-based imputation, were considered, they were not appropriate given the high dimensionality and heterogeneous missingness patterns across countries and indicators. However, we acknowledge that simpler imputation techniques may introduce bias in some cases.

After imputation, all indicators underwent a winsorization procedure to manage outliers and reduce the influence of the extreme values. Values below the 5th percentile were replaced with the 5th percentile value, and values above the 95th percentile were capped at the 95th percentile. Winsorization was applied only after imputation and before normalization so that imputed distributions remained intact and extreme outliers did not skew the rescaling.

Next, normalization was performed using min-max scaling, which transformed the composite ESG performance to a 0–100 range. This step was essential for facilitating comparisons across countries and years. Normalization was applied after the GDP-adjusted scores were computed and after the PLS regression weighting was completed so that the scaling reflected only the final composite output.

Each indicator was smoothed with respect to GDP per capita (x-axis) using LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing), a non-parametric method particularly useful for modeling complex, nonlinear relationships and for being robust to outliers [25,26].

In the LOESS framework, GDP per capita was used as the independent variable (x-axis), while the indicator values were treated as the dependent variable (y-axis). For a given point x, a local subset of data is weighted using a tricubic kernel:

where denotes the normalized distance of point i from the focal value x. A local polynomial regression model is then fitted using weighted least squares to minimize the following objective function:

where are the observed indicator values, are the GDP per capita values, are the LOESS weights, and , , …, are the coefficients of the polynomial. This process was applied individually to each of the 37 ESG-related indicators. The result is a smoothed expected value function for each indicator, conditional on GDP per capita, which allows subsequent analysis to isolate sustainability performance from the confounding effects of the economic scale.

To ensure that ESG scores accurately reflect an underlying sustainability performance metric rather than an economic capacity metric, each component indicator was regressed on GDP per capita, with GDP as the independent variable. The adjustment was made to better isolate the sustainability signal and account for the structural disadvantages faced by lower-income countries [27] because, without a correction for GDP, larger economies may be seen to perform better solely because they have larger resources, potentially masking true differences. By controlling for GDP, the analysis allows for a fairer comparison across countries.

This study adopted a regression framework known as PLS, originally described by [28] but formalized in the soft modeling literature by [29] to construct composite ESG performance scores.

The matrix X contains the adjusted indicator values across countries, and Y represents the target variable—overall ESG performance or pillar-specific performance.

PLS identifies latent components in X that maximize covariance with Y. The weight vectors w and c are computed to maximize the correlation between the projected spaces Xw and Yc. Component scores t = Xw are extracted iteratively, and the PLS model is estimated using these scores to predict Y. The resulting regression coefficients serve as the weights for each indicator, quantifying their relative contribution to the composite score.

The optimal number of latent components in each PLS model was selected using 10-fold cross-validation, minimizing the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP). This approach avoids overfitting by retaining only the components that contribute meaningfully to the model performance and controlling for noise. The final number of components was selected where the RMSEP first reached a local minimum or leveled off, in line with the elbow rule, which is commonly used in dimensionality reduction.

Given the model’s robustness in reducing dimensionality while preserving the variance, three PLS models were implemented. One for each ESG pillar uses indicators as predictors and log GDP per capita as a control. The final performance scores for each pillar are computed as weighted averages of the indicator performances:

These raw scores are rescaled to a standardized 0–100 range using min–max normalization:

This procedure enables coherent cross-country comparisons of ESG performance, over time.

In the final stage of the analysis, the temporal evolution of ESG performance is evaluated using the CAGR, which is a standard metric for measuring the average annual growth of an indicator over a fixed time horizon. The CAGR for country a is computed as:

where denotes the ESG score in the most recent year of data availability (t = 2023), and represents the baseline value in the reference year ( = 2010). This metric provides a smoothed estimate of the average annual rate of change, mitigating the influence of short-term fluctuations and enabling meaningful comparisons across countries and indicators.

The estimated growth rates are classified into four qualitative growth categories, which reflect both the degree and direction of change. A growth rate above 1% per year is considered reflective of significant movement toward progress, thus supporting long-term sustainability targets. Growth rates of 0.5–1% are fair in terms of progress but demonstrate that continued improvement is needed. Growth rates on the order of −1% to 0.5% essentially demonstrate no or limited changes. Finally, all values below −1% are indicative of declining ESG performance. This classification system provides a recognizable utility for potentially tracking progression and determining whether policies should be adjusted. This classification typically retains the integrity of the benchmark metric and provides quantitative benefits.

Cluster analysis was used to group countries based on their ESG performance, which allows the identification of natural groupings in the data. The best number of clusters is identified with the elbow method that plots the within-cluster sum of squares (WSS) versus a range of values of k. The optimal number of clusters is when the rate of decrease in WSS decreases dramatically, as in [30,31]. Next, the K-means algorithm, introduced by [32], is used to partition countries into distinct clusters by minimizing the within-cluster variance. This approach is consistent with the clustering practices outlined by [33,34]. Lastly, to examine the structure of the data further, hierarchical clustering is used, using Ward’s minimum variance method [35] to minimize within-cluster variance at all steps of the agglomerative process. This produces a dendrogram that illustrates the nested cluster structure and improves the interpretability. This method is based on [36,37], who posit that it is reliable for social and economic research. These techniques provide tactical insights useful for benchmarking and policy development at the European level.

3. Results

The results presented in this section summarize the ESG performance dynamics across EU regions based on the proposed analytical framework. Using a combination of LOESS smoothing, GDP-normalized indicators, and PLS regression, the analysis identifies key patterns of variation and change within the environmental, social, and governance pillars. The subsections highlight both cross-sectional disparities and temporal trends, offering insights into how different regions have evolved over the 2010–2023 period. The interpretations are grounded in the empirical outputs and supported by the classification and clustering techniques introduced in the methodology.

3.1. Empirical Results of the PLS Models

3.1.1. Main Drivers of the Environmental Pillar

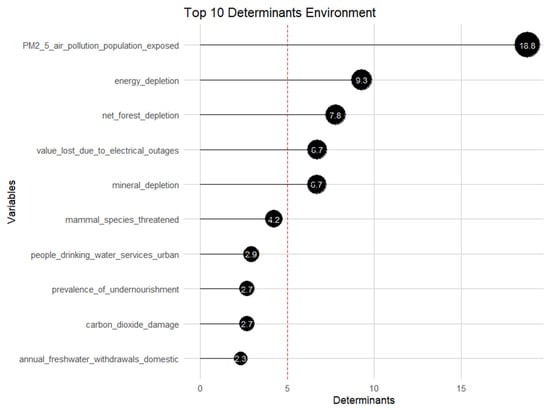

The determinants of environmental performance across the Member States of the European Union were assessed using a PLS regression model, applied to a set of 50 environmental indicators. As illustrated in Figure 1 and detailed in Table 1, the first five variables account for 49.3% of the total explained variance, suggesting the concentrated influence of a small subset of indicators.

Figure 1.

Top 10 determinants of the environmental pillar.

Table 1.

Top 10 determinants of the environmental pillar.

The most significant factor is the proportion of the population exposed to PM2.5 concentrations exceeding the threshold recommended by the World Health Organization. This indicator alone contributes over 18.8% to the total model variance. The prominence of this variable underscores the critical role of air quality in determining the environmental performance. Exposure to PM2.5 is associated with adverse health outcomes and broader economic costs. It was estimated that air pollution reduces GDP by approximately 0.8% through its effects on labor productivity and public health [38]. Similarly, ref. [39] reports that prolonged exposure to air pollutants is responsible for around 400,000 premature deaths annually in the EU, further highlighting the socio-economic implications of environmental degradation. In regions where pollution levels are persistently high, environmental quality may become a barrier to investment and development. The European Environment Agency [40] explicitly links pollution control to the long-term competitiveness and resilience of the Union’s economy.

The second and third most important variables are energy consumption and net forest depletion, expressed as percentages of gross national income, which contribute 9.3% and 7.8% to the model, respectively. These indicators reflect the pressure on natural resources and the sustainability of national economic activity. It was noted that energy efficiency and responsible resource use have become critical for corporate environmental performance and investment decision-making [41]. In addition, ref. [42] shows that firms associated with high emissions or unsustainable land use are increasingly exposed to legal and reputational risks, which can affect both financial performance and access to capital.

In contrast, variables such as annual domestic freshwater withdrawals and per capita carbon dioxide emissions appear to be less influential in the model. Although their current explanatory power is limited, they remain conceptually important and are retained in the construction of the composite indicator. As the structure of the economy continues to evolve, particularly in the context of digitalisation and climate-related innovation, the relevance of these indicators may increase.

In Table 2, the composite scores for the selected EU Member States are reported, with a focus on the 2023 outcomes. France and Germany stand out with perfect environmental scores, reflecting consistent and effective sustainability policies throughout the period of analysis. Their performance remained resilient even during the COVID-19 crisis, suggesting a strong institutional capacity to maintain environmental targets during times of exogenous shock. Germany’s continued implementation of the Energiewende strategy during the pandemic, which aimed to reduce dependency on fossil fuels and expand renewable energy infrastructure, illustrates this long-term commitment [43]. France has increased its investment in sustainable infrastructure, particularly in transport and energy, while reinforcing its alignment with the Paris Agreement targets [44]. These national trajectories support the findings of [45], who identify a positive causal relationship between the integration of ESG practices and market performance in both countries.

Table 2.

Environmental pillar scores.

In contrast, Italy, Finland, and Ireland, which ranked among the top five in the early part of the study period, experienced relative declines during the pandemic. Italy was severely impacted by the economic consequences of COVID-19, which constrained green investments and delayed the implementation of sustainability projects [46]. Finland struggled with energy transition challenges, particularly due to limited infrastructure and redirected public resources during the health crisis [47]. Ireland’s difficulties in mitigating emissions from its agricultural sector further hampered progress in environmental performance during this time. Several countries, namely Sweden, the Netherlands, and Denmark, demonstrated notable improvements in the post-pandemic period.

At the lower end of the ranking are several countries from Southern, South-Eastern, and North-Eastern Europe, including Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, and Lithuania. These countries face persistent, structural, and institutional challenges. The weak enforcement of environmental regulation, combined with competing economic priorities, continues to impede sustainability outcomes [48]. Many of these countries also inherited industrial infrastructure from the socialist era, complicating the transition to greener models of development [49].

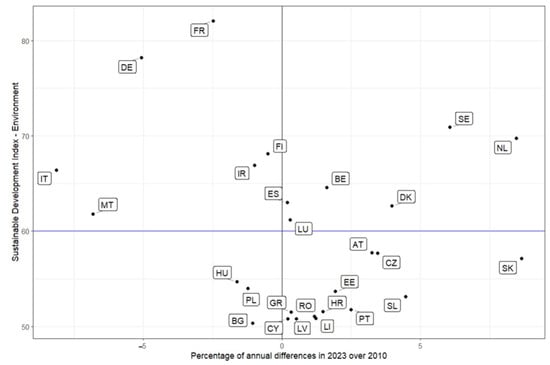

Figure 2 shows the percentage change in environmental performance scores for EU member states from 2010 to 2023. Countries such as Italy, Germany, Malta, and France had and continue to have high scores in 2023, but their scores are lower than in 2010. This decline is possible due to reduced environmental investment over the last three years, particularly after COVID-19. While the countries made measurable progress with environmental investment and policy in the last ten years, their performance in recent years has been sufficient to keep them at the top of the environmental performance ranking. The scores of Finland, Spain, Ireland, and Luxembourg, all countries with above-average scores, demonstrate little movement between the years and are indicators of long-term strategies for positive performance in the environmental sector and regulatory enforcement. A similar finding of low change can be seen in many Southern and Central countries, but their scores are still lagging compared to the EU average sector. This lag includes dependence on fossil fuels, significant air pollution, limited green investment, and a lower level of public environmental awareness. Countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands have both high scores and high rates of change since 2010. Positive rates of change are likely to be supported by significant investments in renewable energy practices and circular economy processes. Slovakia demonstrated significant improvement between years, but overall, it will remain below the EU average, reflecting a lower initial baseline.

Figure 2.

Percentage change in environmental performance scores between 2010 and 2023.

3.1.2. Main Drivers of the Social Pillar

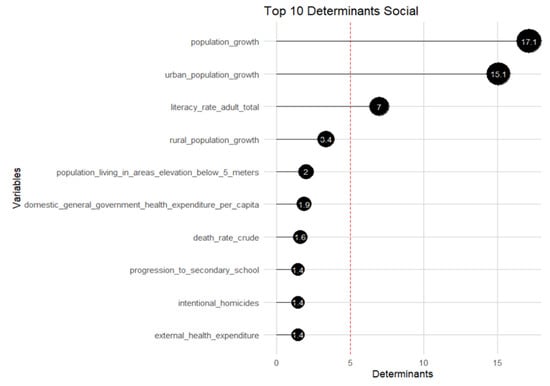

The social dimension of ESG performance was evaluated using a PLS model applied to 102 indicators. As shown in Figure 3 and detailed in Table 3, the top five determinants account for 44.4% of the model’s explained variance. The most influential variable is population growth, contributing 17.1% to the total variance. Population expansion supports labor market growth and stimulates demand for social services, requiring governments and firms to invest in healthcare, education, and social infrastructure [50].

Figure 3.

Top 10 determinants of the social pillar.

Table 3.

Top 10 determinants of the social pillar.

The next most important factor is urban population growth (15.1%). Although urbanization can contribute to economic activity and infrastructure growth, there is also the potential for urbanization to increase inequality for those who do not have equitable policies in place [51]. The adult literacy rate is a measure of the social capacity to participate in the economy, develop human capital, and ultimately enhance productivity over the long term. A high literacy rate indicates the ability of adults to access employment and is a measure of potential upward mobility. High literacy levels can also improve community cohesion [52,53]. These are indicators of regional vulnerabilities that can be generated by gaps in agricultural productivity and exposure to climate risk [54,55] and reiterate the importance of the sustainable and targeted approach needed to develop practices.

Table 4 indicates the social scores across EU Member States over the period 2010–2023. Germany consistently ranks first, reflecting a strong and adaptable social space [56]. France remained among the top three countries throughout the period, including during the COVID-19 pandemic, confirming the robustness of the French welfare model [57]. The Netherlands progressed to second place in 2023, reflecting a clear commitment to balancing social welfare infrastructure [58]. Finland, Sweden, and Denmark also ranked highly, showing that social policy is embedded in comprehensive protection systems that emphasize sustainability and the active engagement of social structures [59]. Ireland and Slovakia progressed rapidly, with Ireland ranking 10th in 2023. Finally, Croatia and Czechia show steady and improving performances.

Table 4.

Social pillar scores.

At the bottom end of the scale, Romania was ranked last, indicating issues related to outdated and impractical social infrastructure. Poland, Greece, and Hungary face ongoing socio-economic challenges [60]. While Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, and Croatia have shown some gains, they remain below average, suggesting ongoing institutional and investment gaps.

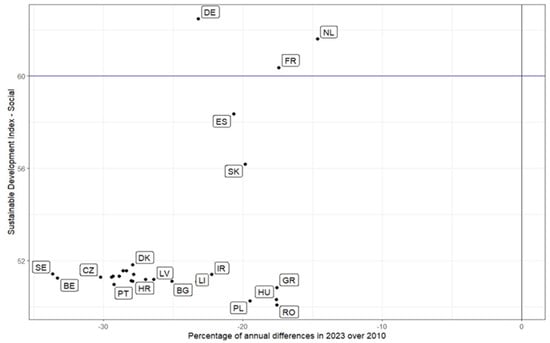

Figure 4 shows the percentage point change in the social pillar scores from 2010 to 2023. A broad decline in performance between 2010 and 2023 is clearly evident to varying degrees across all Member States. Most notably, Germany, the Netherlands, and France maintained their above-average scores, which suggests some relative stabilization of their social systems and ongoing commitment to policy efforts, despite the downward trend in scores.

Figure 4.

Percentage change in social performance scores between 2010 and 2023.

In contrast, the majority of EU countries experienced declines of up to 15%, reflecting the substantial impact of recent exogenous shocks. The COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing war in Ukraine have strained national budgets, disrupted social services, and contributed to widespread deterioration of social infrastructure across the Union.

3.1.3. Main Drivers of the Governance Pillar

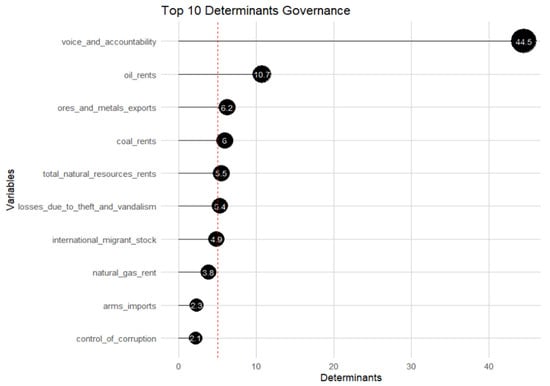

The governance performance across the countries of the European Union (EU) is largely explained by a few prominent factors. As shown in Figure 5 and detailed in Table 5, the most important factor is Voice and Accountability, which alone explains over 44.5% of the explained variance in the PLS model. This indicator explains the nature and extent to which citizens can participate in governance and be held accountable for their institutional actions. These facets are associated with sustainable financial performance and lower investment risk.

Figure 5.

Top 10 determinants of the governance pillar.

Table 5.

Top 10 determinants of the governance pillar.

The second most impactful factor is oil rents (10.7%), which emphasizes that governance structures are heavily influenced by the management of resource revenue. Responsible management of oil rents can make it conducive to greater accountability, lessen instability, and establish compliance with environmental standards [61]. In addition, mineral and metal exports, which are ranked third, can promote governance structures due to an increase in national income and the ability to enforce regulations. Efficient management helps control corruption and promote environmental protocols. Coal rents (6%) and total natural resource rents (5.5%) further illustrate the importance of resource-based revenue in shaping governance quality. Although coal-related activities generate substantial economic value, they pose considerable environmental and social risks. Therefore, incorporating rigorous environmental regulations and revenue transparency is vital. Together, these five variables explain 72.9% of the total variance in governance scores, underscoring their central role in the composite indicator.

Table 6 provides a longitudinal perspective on governance performance across EU countries over the period 2010–2023, segmented into five intervals: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, 2020–2023, 2022–2023, and 2023. The Netherlands and Sweden consistently top the rankings, achieving perfect or near-perfect scores throughout the observed periods. They have well-developed regulatory systems that support innovation, protect property rights, and ensure a level playing field. Their regulatory policies are often considered models of good practice internationally [62].

Table 6.

Governance pillar scores.

France also ranks third, with a score of 78.37% in 2023. Studies attest that France has a well-developed legal system and robust public institutions that ensure compliance with the law and protect citizens’ rights [63]. France’s governance is characterized by a combination of strong state support for development, such as that seen in the areas of health, education, and infrastructure.

In terms of average performance, Belgium, Spain, and Portugal show strong government scores, indicating their rigorous government systems. In Belgium, difficulties in governing and implementing policies are amplified by the complexity of the federal system and political tensions between the regions of Flanders and Wallonia [64]. In Spain, problems related to the transfer of power to autonomous communities and secessionist tensions, such as those in Catalonia, affect the coherence and efficiency of governance across the country [64]. Despite significant progress in strengthening institutions and fighting corruption in Portugal, problems related to administrative efficiency and the implementation of structural reforms persist [65]. Both Spain, Portugal, and Belgium have had difficulties managing the economic and financial crises of the last ten years, negatively affecting the perception and efficiency of governance.

Croatia, Estonia, and the Czech Republic demonstrate moderate performance, with Croatia and the Czech Republic showing a constant state in their government scores, with a decrease only at the onset of the pandemic, and Estonia showing a positive trajectory, climbing to 16th place in 2023.

Romania and Bulgaria are at the lower end of the spectrum, with Romania ranking last in 2023, indicating serious challenges in terms of corruption, institutional weaknesses, and challenges in implementing reforms. Additionally, the conflict between Ukraine and Russia has had an economic and political impact. Romania faces a high level of corruption at all levels of government, which undermines public trust in institutions and affects the efficiency of public administration [66]. In Bulgaria, the lack of transparency and accountability in the management of public resources, as well as delays in the implementation of the necessary structural reforms, contribute to the low scores of both countries on the Government pillar [67].

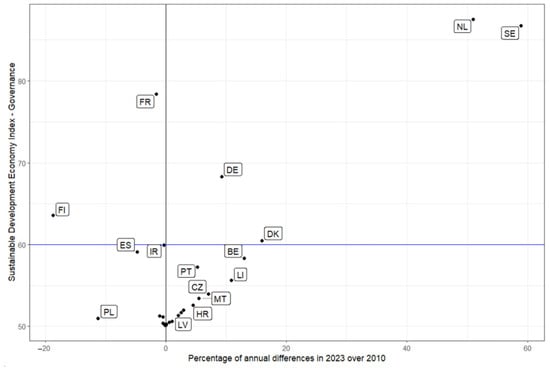

Figure 6 shows the percentage differences from 2010 to 2023 for the governance pillar. Recording high scores but also decreases, Finland and France show a deterioration in government performance. Although the percentage differences are large, they managed to rank at the top of the ranking with high scores. In the case of Finland, the decline that occurred after 2020 appears to be linked to the COVID-19 crisis. Although public trust in institutions remained strong, the government’s swift use of emergency powers, the centralization of decision-making, and heavy reliance on expert advice meant that normal democratic processes were temporarily sidelined. With much of the country’s focus and funding directed toward managing the health crisis and propping up the economy, other areas of governance may have received less attention, leading to a loss of transparency and a strain on broader institutional functioning [68].

Figure 6.

Percentage change in governance performance scores between 2010 and 2023.

Denmark and Germany did not register significant percentage differences, and their scores are above average. These effects are due to stable policies and governments supporting sustainability. The vast majority of countries in Southern and Central Europe have below-average scores, but without significant differences. They have encountered problems in improving governance performance caused by civic participation in the decision-making process, high levels of corruption and lack of transparency, incoherent public policies, and a multitude of conflicts of interest.

Sweden and the Netherlands recorded significant increases in 2023 compared to 2010, and also have high, above-average scores due to civic involvement in public issues, strong anti-corruption programs, and coherent policies that help with long-term sustainable planning.

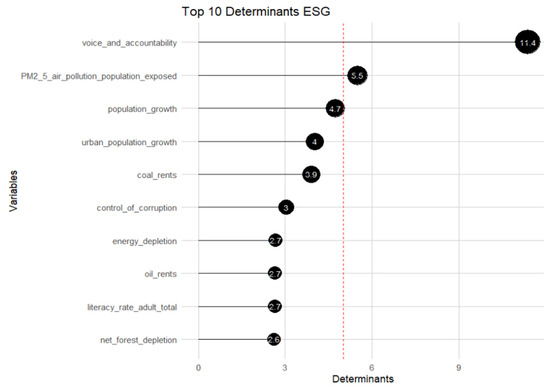

3.1.4. Main Drivers of the Three Pillars

The findings of the PLS model for the composite index of EU countries are shown in Figure 7 and detailed in Table 7, where all variables derived from the three ESG pillars were entered in one step, leveraging the PLS’s ability to mitigate multicollinearity. The top 10 determinants of the model estimated 40.5% of the variance of the model, but all variables were retained to keep the index fully intact. The strongest contributors appear in the governance pillar, particularly the governance indicators of voice and accountability and control of corruption, which emphasize how critical institutional quality is to overall performance. This is in agreement with the findings that quality, effective, and transparent governance structures are fundamental to economic development and social cohesion within the EU. Environmental and social variables shown to be important were PM2.5 pollution, population growth, urbanization, access to healthcare, and the literacy rate. Overall, this reinforces the role of environmental resilience and human capital in measuring national economic strength.

Figure 7.

Top 10 determinants of ESG.

Table 7.

Top 10 determinants of ESG.

A review of the total economy sector index from 2010 to 2023, presented in Table 8, indicates that the Netherlands and Sweden consistently achieved excellence, scoring perfectly or near-perfectly over the given period. Their continued position at the top can be attributed to their balanced performance across environmental, social, and governance aspects.

Table 8.

Comparative analysis of the EU Member States’ indices (2010–2023).

Germany remains one of the top-performing countries in terms of overall performance, remaining in third position in 2023 and demonstrating the continued resilience and effectiveness of its institutional framework. Denmark, France, and Finland are also performing reasonably effectively, although there are trends of declining performance over the past several years, signifying opportunities for further improvements. Portugal and Spain also improved their overall performance, with Portugal making a slight upward shift in the last year of the analysis. Mid-performance countries, such as Lithuania and Italy, display solid performance but also display slight uncertainties, perhaps through policy or structural constraints.

Ireland and the Czech Republic have made steady improvements over time in both their total scores and rankings. At the bottom of the index, Romania and Bulgaria continue to face significant obstacles. Romania was second from the bottom in 2023, raising concerns about lasting issues that cross multiple pillars. Greece and Slovenia remain at the bottom of the distribution, indicating structural limitations. Meanwhile, Belgium, Estonia, Croatia, and Poland have shown signs of improvement, reflecting structural improvements and efforts at both the institutional and policy levels.

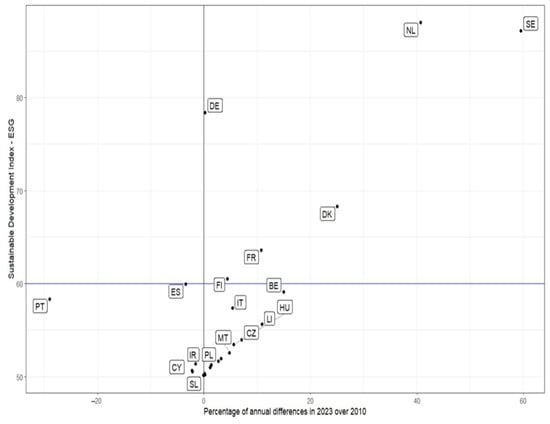

Figure 8 shows the percentage differences in ESG scores from 2010 to 2023. Recording below-average scores and seminative decreases, Portugal shows a deterioration in environmental performance. This is caused by the high level of pollution, inefficient waste management, high unemployment rate, and precarious work conditions, such as global economic crises that have had a long-term impact on Portugal.

Figure 8.

Percentage change in ESG performance scores from 2010 to 2023.

Finland, Germany and France did not show substantial percentage differences, and their averages are distinctly above average. This is expected because each country clearly demonstrates rigid and structured actions and policies toward sustainability. Most Southern and Central European countries have below-average scores. They have encountered problems in improving environmental performance caused by the slow transition to renewable energy, the development of the health and education system, and the implementation of anti-corruption policies. Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands reported considerable increases from 2010 to 2023, and they also have high scores, with well-developed waste strategies, solid renewable policies, and strong social equality protections through employee rights and transparency and stability in political practices.

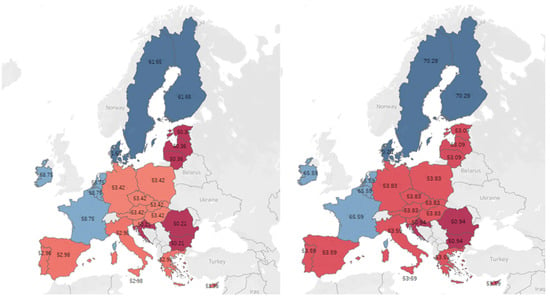

3.2. Empirical Results of the Cluster Analysis

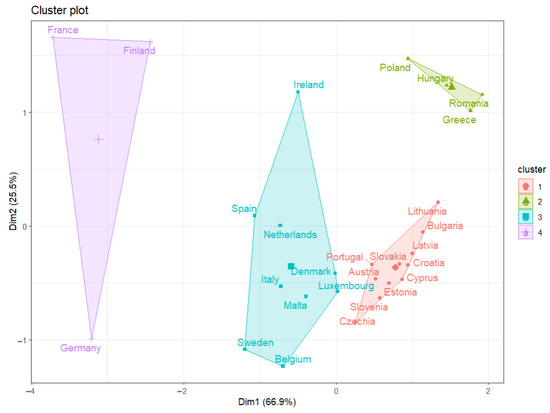

By applying the k-means clustering method in calculations based on the governance, social, and environmental pillars derived from the PLS analysis, this study identifies significant regional patterns among EU countries for 2010. As noted in Figure 9, the first principal component represents 66.9% of the total variance (x-axis) and shows a strong discriminatory ability across the member states. The second principal component stands alone in explaining 25.5% of the variation, capturing more nuanced variation.

Figure 9.

Cluster analysis for the year 2010.

The analysis of the data results in the identification of four main clusters, namely:

- Northern and Western European Cluster (identified by purple)—This cluster is composed of Finland, France, and Germany, which have high levels of governance capabilities, social concerns, and high levels of economic development.

- Eastern European Cluster (identified by blue)—This cluster includes members Ireland, Spain, Netherlands, Denmark, Italy, Malta, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Sweden, which have noted similar shaping of their economies through evolving institutions and social frameworks, suggesting moderate levels of development.

- Central and Eastern European Cluster (identified by green)—Members include Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Greece, which have similar transitional experiences and structural characteristics relative to the historical and economic contexts.

- Southern Europe Group (identified in red)—Members include Lithuania, Bulgaria, Latvia, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Slovenia, Czechia, Austria, Portugal, and Slovakia, with shared regional challenges specific to the Mediterranean and post-socialist economic contexts.

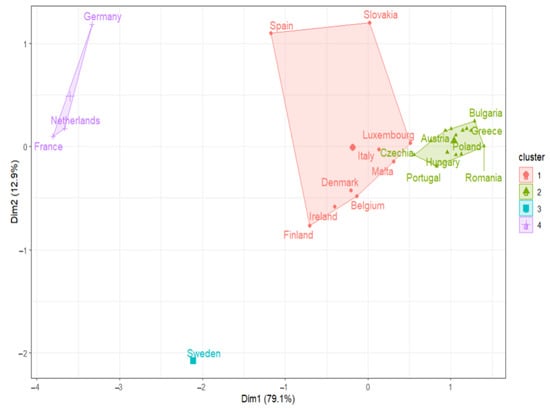

A similar clustering analysis was conducted for 2023 to examine whether the composition of the poles of public sector performance changed over time. In Figure 10, we observe four distinct clusters. Therefore, there is a mixture of stability and change in the governance, social, and environmental structures of the EU member states.

Figure 10.

Cluster analysis for the year 2023.

- Northern Cluster (purple area)—This cluster is now made up of the Netherlands, Germany, and France, located within the upper region of Dimension 1. Their continued presence in one of the top positions indicates their continued top-tier performance and converging potential in public sector performance on all three pillars.

- The Central European Cluster (red area)—Spain, Slovakia, Luxembourg, Italy, Malta, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, and Belgium–represents countries in the stable central area of Europe. Their shift in relative position in this cluster reflects incremental changes in governance and the structures of socio-economic systems.

- The Emerging South-East Cluster (green area)—Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Cyprus, Latvia, Slovenia, Estonia, Hungary, Austria, Portugal, Romania, Greece, and Lithuania–on this map indicates progressive changes, especially with regard to the upward changes along Dimension 2 for Australia. Some countries, such as Bulgaria, show significant positive progress. This indicates that structural changes and progress would indicate convergence with better-performing EU countries.

- Scandinavian Cluster (blue area)—Represented solely by Sweden, while this is a cluster, it is reflective of a unique position that Sweden maintains, further reflecting consistent institutional capacity as well as the dynamics in which the region is governed that influence their public sector performance.

When comparing the results of the two periods, some countries, such as Germany and France, remain strong performers in the ESG index, showing notable improvements. The positions of some countries, such as Sweden and Spain, have changed within their groups, which may suggest changes in their relative rankings. There is a change in the importance of the dimensions. In Figure 9, size 1 accounts for 66.9% of the variance (2023 showed an increase to 79.1%), and size 2 accounts for 25.5% (2023 showed a decrease to 12.9%). This suggests that the factors represented by Dimension 1 have become more important in differentiating the performance of the economic sectors of these countries.

3.3. Empirical Results of the Regional Analysis

3.3.1. Spatial Differentiation in ESG Pillars Across EU Regions

Given the scarcity of regional ESG data, European Union regions were classified based on country-level scores into the following groups: Scandinavian (Denmark, Sweden, and Finland), Baltic (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), Western (Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, Netherlands, and Austria), Central (Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and Slovakia), Southern (Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Malta, Portugal, Spain, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Romania), North-West (Ireland, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, and France), and South-East (Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Cyprus, and Croatia).

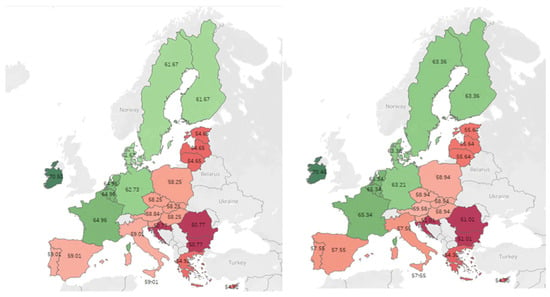

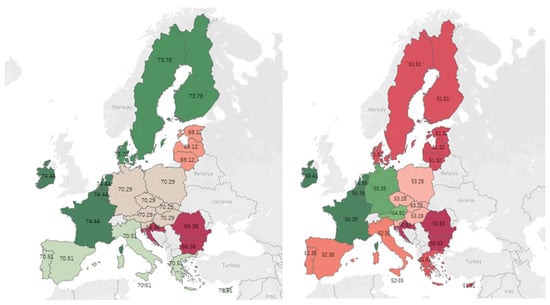

For the environmental pillar, the analysis of the 2010 and 2023 scores shown in Figure 11 reveals the Scandinavian region as a consistent top performer, with the Baltic region following closely due to similar regulatory frameworks. Both have invested significantly in green technologies and renewables, such as wind, solar, and hydropower [69]. The Western, Central, and Southern regions show comparable performance, shaped by their industrial histories and infrastructure inefficiencies [70]. The South, in particular, remains reliant on fossil fuels but is actively transitioning to renewables [69]. The Eastern region ranks lowest, reflecting outdated infrastructure, delayed post-communist industrialization, and economic priorities focused more on poverty reduction than on environmental policy [71].

Figure 11.

EU regions’ environmental pillar scores in 2010 (left) and 2023 (right).

Relative to the 2010 findings, the Scandinavian Region continues to be the leader in environmental governance and policies resulting from environmental governance. The Western Region is the next best region for environmental governance. In the 13-year period from 2010 to 2023, the Western Region maintained a relatively consistent governance performance rating and had the highest governance rating relative to other regions in Europe. The Southern Region continues to perform relatively poorly because the governance scores are consistently low, which implies that the capacity to enforce laws and regulations continues to be a problem. The repetition of patterns between 2010 and 2023 suggests that governance challenges at the economic, political, and structural levels continue to shape environmental outcomes in EU regions.

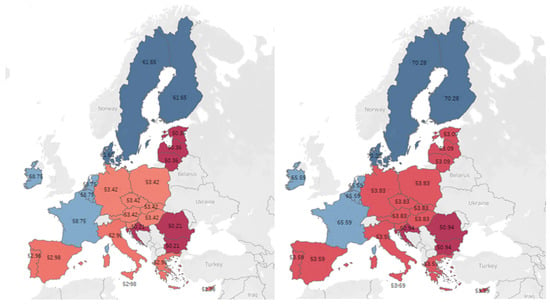

The Scandinavian Region, on average, reports the highest scores relative to governance, as identified in Figure 12 above, which is, again, consistent with the 2010 findings, demonstrating evidence of effective policies and implementation of sustainable environmental policy over time. Likewise, the Western Region shows strong governance measures and reliable governance systems. The identifiable characteristics of the two regions include a high level of transparency, capable institutions, high levels of public engagement in the policy process, and significant anti-corruption measures [72]. The Baltic, Central and Southern Regions reported similar governance scores, suggesting that they demonstrate comparable sustainability standards and ongoing reform. The slower progress in the Baltic, Central, and Southern Regions is attributable to mid-range corruption and variable administrative capacities [73]. The Eastern Region performed the worst relative to other regions, indicating that governance reform is the predominant form of rehabilitation needed to support environmental governance. High levels of corruption, compromised institutional capacity, and law enforcement limit environmental governance and sustainable development.

Figure 12.

EU regions’ governmental pillar scores in 2010 (left) and 2023 (right).

The Scandinavian Region continued to rank first among the regions for governance compared to 2010, suggesting that this region has maintained a more consistent approach to governance in terms of offering access to transparency, accountability, civic engagement, and strong anti-corruption efforts [74]. The Western Region ranked second. This space has rapidly improved, predominantly due to significant structural reforms aimed at increasing efficiency and transparency [75]. The Southern region is still battling significant governance issues, particularly following social issues caused by poor governance and high levels of corruption, and accordingly, efficient government engagement in social issues.

Again, looking specifically at the social pillar, as shown in the scores in Figure 13, both the 2010 and 2023 scores for the Scandinavian and Western Regions indicate that they were the highest, supported by sustainable social protection systems, strong, reliable public services, and relevant redistributive and equitable policies. When compared against each other, both the Scandinavian and Western Regions show lower levels of poverty and social exclusion than their regional neighbors, which in turn indicates a robust economy [76]. Unlike the environmental and governance pillars, all other regions were relatively close in scores to each other, suggesting a relatively comparable level of sustainability on the social front. In the Eastern Region, the last region, there was less of a gap than in the other pillars, most likely due to EU social policy standards. The consequence of this is that all the regions are more comparable in terms of poorer social protection mechanisms, generally lower quality of service, and higher levels of poverty.

Figure 13.

EU regions’ social pillar scores in 2010 (left) and 2023 (right).

Compared to 2010, all regions have lower social scores. This is due to the social factors of the last three years, which have destabilized the European Union. These factors had a major impact, and the pandemic crisis presented a major exogenous shock from which many countries are still trying to align economically. Moreover, the war between Ukraine and Russia over the past two years has put pressure on the European Union, amplifying long-term economic instability.

The ESG scores for 2010 and 2023, as shown in Figure 14, indicate that the Scandinavian and Western Regions consistently performed best, reflecting their robust policies and regulatory frameworks for long-term sustainability. The Baltic, Central, and Southern Regions showed similar intermediate scores, suggesting shared sustainability characteristics. In contrast, the Eastern Region ranked lowest in both years, underscoring the need for targeted reforms to enhance ESG performance and overall regional sustainability.

Figure 14.

EU regions’ ESG scores in 2010 (left) and 2023 (right).

3.3.2. Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) Analysis

To evaluate temporal trends in environmental outcomes, Table 9 provides a comparison of the CAGR across European Union regions (for three periods: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2023). Given that reasonable improvements in the environmental outcome were made only in the Western Region in the 2010–2014 period, the Western Region can be interpreted to have made the first reasonable headway—this suggests that effective action had begun with the implementation of long-term sustainable development policies. All the other regions made relatively negligible improvements in the first two time periods, highlighting the continuing structural inertia with regard to critical realities, institutions, and competing policy and program priorities.

Table 9.

Progress of EU regions on the environmental pillar.

During the pandemic and post-pandemic years (2020–2023), several regions, including the Scandinavian, Central, and Southern regions, registered a deterioration in environmental scores, suggesting that health and security crises diverted resources from environmental initiatives. The Baltic, Eastern, and South-Eastern regions consistently underperformed across all periods, indicating persistent institutional and financial constraints. Overall, the findings underscore uneven progress and highlight the need for accelerated, regionally tailored environmental strategies.

Table 10 provides a synthetic overview of regional social sustainability trends across three periods: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2023. Substantial progress was observed in the Baltic, Western, Eastern, North-West, and South-East regions during 2010–2014, suggesting effective policy frameworks that promoted social development in the early years of the analysis.

Table 10.

Progress of EU regions on the social pillar.

Fair progress, though requiring acceleration, characterized the Scandinavian, Northern, Central, and Southern regions, reflecting stable but gradual advances in the social infrastructure. In contrast, limited or no progress was evident between 2015 and 2019 in the Western, Southern, Eastern, and South-Eastern regions, coinciding with broader economic disruptions and policy stagnation.

A concerning pattern of performance deterioration emerged across all regions during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods (2020–2023), as well as pre-pandemic setbacks in Northern and Central Europe. These declines appear to be driven by the COVID-19 crisis and broader geopolitical instability, underlining the fragility of social progress in the face of exogenous shocks.

A comparative analysis of governance score dynamics across EU regions from 2010 to 2023 reveals some important trends (see Table 11). Notable growth was registered early (2010–2014) in the Scandinavian, Northern, Western, Central, Southern, and Eastern regions, and was directly related to the implementation of inclusive and effective governance reforms. After this growth, continued governance improvements were observed, mostly in the Western Region. Although this region experienced constant improvements across all time periods, the Northwest region similarly secured significant scores over the last two periods. The Scandinavian and Northern regions later demonstrated further developments post-2020. Fair but insufficient progress was observed in the Baltic, North-West, and South-East regions, which indicates that some systems of governance were criticized for falling short of the lasting and system-wide reforms required to achieve the full benefits of governance reform investments.

Table 11.

Progress of EU regions on the governance pillar.

In contrast, most of the Central, Southern, Baltic, and South-Eastern regions’ governance score progress was limited or stagnant during the 2015–2019 and 2020–2023 periods. This reveals potential structural inefficiencies in governance systems, worsened by the combined effects of the pandemic and heightened geopolitical tension. Lastly, it should be noted that the East region experienced a governance decline in the most recent time period.

A summary assessment of ESG performance demonstrates distinct regional trajectories over time, which reflect the disaggregated pillar analyses presented in Table 12. The Western and North-West regions have made continuous and significant improvements, demonstrating that the paired synergies work effectively in these regions because of the established and mature institutional frameworks and asset-coherent sustainability strategies. The Scandinavian Region still exhibits a high level (close to the ceiling) but also began to re-accelerate in the last time period, reinforcing its position as a leader in integrated ESG outcomes. The Central and Baltic regions also improved in the more recent period, which suggests strengthened institutional and environmental frameworks. Conversely, the Southern, Eastern, and South-East regions displayed only limited or inconsistent improvements, sometimes affected by structural limits, remedial governance capacity, or economic and geopolitical shocks. On a more positive note, no region recorded a systematic decline in ESG performance over the pre- and post-COVID periods. Taken together, the overall results suggest relative stability and gradual convergence toward EU sustainability standards.

Table 12.

Progress of EU regions on ESG scores.

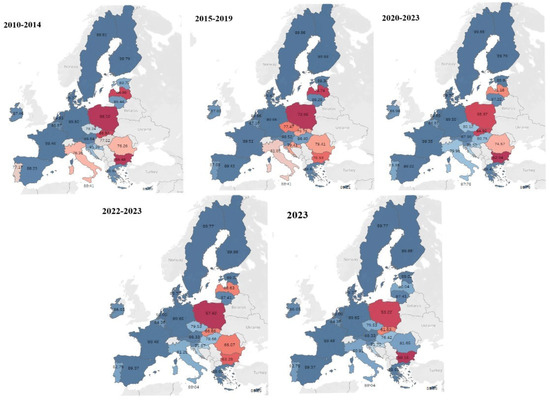

3.4. Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis

As part of the robustness and sensitivity analyses, the ten most influential determinants from each pillar were consolidated, and a PLS model was applied to assess the composite performance. A longitudinal ranking, as shown in Table 13, was developed for EU countries across five time frames (2010–2014, 2015–2019, 2020–2023, 2022–2023, and 2023).

Table 13.

Longitudinal Scores of EU Member States Based on Key ESG Determinants (2010–2023).

The Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden consistently emerged at the top of the rankings, obtaining near-perfect scores, which highlights some of the best regulatory frameworks and innovation policies and institutional quality measures that have consistently been referenced as best practice indicators in the Nordic Region. Denmark continues to outperform other countries, obtaining the 3rd position in 2023, with a score of 89.77%.

For countries in the mid-range, France, Spain, and Germany continued to display solid and stable performance. Their governance and social systems are stable and resilient. Estonia’s performance demonstrated rising momentum, moving up to the 8th position in 2023.

At the bottom end of the ranking, Romania and Bulgaria again rated the lowest, with Romania ranking the lowest in 2023. Structural weaknesses in institutional capacity, corruption, and delayed reform implementation continue to hinder progress, which has been further exacerbated by the spillover effects of the Russia–Ukraine conflict.

Analysis of the 30 most significant determinants identified in each pillar shows that overall scores have substantially increased at the regional and country levels. This should encourage authorities to consider ESG analysis, specifically for the above variables, and take action to find the best possible actions to reduce deficiencies.

To assess the performance of EU Member States and regions with the most important ESG determinants, spatial maps were constructed for every time interval. As shown in Figure 15, countries from the Nordic Region, with the exception of Latvia, achieved the highest scores and confirmed the previous analysis. Countries from the Western Region seem to follow a good trajectory, almost reaching the possible optimum ESG scores by 2023. The Central and Southern Regions seem to maintain the trend of improving their overall performance in all years. Romania from the South-Eastern Region seems to have a large jump in performance in 2023, indicating that potential government policies and actions, depending on the ESG variables, could show significant gains. Poland appears to be performing less than most countries in the region, possibly due to the economic turbulence associated with the ongoing regional conflict.

Figure 15.

Temporal Mapping of ESG Scores for EU Member States Using Top Determinants from Each Pillar (2019–2022).

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive macroeconomic analysis of sustainability outcomes across EU regions, supporting the contextualization of ESG indicators against long-run economic resilience and structural convergence of economies. Employing PLS regression, this study identifies significant latent factors in regional differences in ESG indicators while circumventing methodological problems that have plagued previous research, including multicollinearity and overlap between indicators related to environmental performance and low sample size per regional dimension.

From a macroeconomic perspective, one of the most notable findings is the central role played by governance. Compared to environmental and social performance, the analysis shows that governance contributes more significantly to the variation in composite ESG scores, especially through indicators such as “Voice and Accountability” and “Control of Corruption”.

This result likely stems from greater institutional heterogeneity across EU Member States, especially between newer and older members, compared to the more convergent nature of environmental and social policy frameworks that are more closely aligned with EU directives [4,77]. While environmental and social standards may benefit from harmonization through EU regulations, governance remains deeply embedded in national political-administrative traditions, resulting in greater variability and higher explanatory power in the PLS models.

These results reinforce earlier findings on the role of institutional factors in shaping sustainable development trajectories, as seen in [78], who emphasized the relevance of governance actions and social norms in fostering sustainability-oriented intentions at the enterprise level through PLS-SEM modeling.

This finding contrasts with firm-level ESG studies, in which environmental factors often dominate due to market expectations, reporting pressure, and reputational risks [79,80]. In our regional-level model, governance emerges as a systemic enabler of sustainable development, influencing not only financial and institutional resilience but also the efficacy of environmental and social policy implementations.

These results are also consistent with the existing literature presented in the previous sections, including the works of [15,16], which indicate a relationship between institutional quality and improved sovereign risk ratings along with lower sovereign bond spreads. Additionally, as noted by [17], governance actors were shown to be paramount determinants of operational and financial performance in the banking industry, and in that case, a form of governance was useful in shaping sustainable finance. However, in this case, governance has broader implications—it not only enhances financial stability but also multiplies the impact of environmental and social policies across member regimes.

From a macroeconomic perspective, environmental performance reveals stark regional disparities closely linked to the varying levels of institutional development and economic capacity among EU Member States. Countries in Northern and Western Europe, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, continue to achieve solid results due to past investments in renewable energy and waste systems which are common characteristics of the circular economy. Countries in the Southern and Eastern regions, such as Bulgaria, Romania, and Greece, experienced challenges related to diminished fiscal capacity, fixed assets nearing the end of life, and enforcement challenges.

This regional divergence is in line with the findings of [79], who highlighted the complex interplay between labor market conditions, productivity, and institutional structures in shaping macroeconomic outcomes through panel and cluster analyses across EU countries.

In addition, [80] provides supporting evidence through a DEA-based efficiency analysis of urban development in European and global cities, reinforcing the importance of spatial disparities and institutional gaps—elements that directly align with our findings on governance bottlenecks and ESG heterogeneity across NUTS2 regions.

Nevertheless, consistent with [13] ’s findings, the shift to environmental improvement is contingent on investment and institutional quality. Furthermore, utilizing GDP normalization and then LOESS smoothing allowed a more reflective view of environmental improvements by decoupling it from the size of the economy, removing an ingrained systematic bias of comparative ESG scoring.

The social dimension has experienced an even more uneven progression, as COVID-19 disrupted human capital development, access to services and demographic stability across nearly all Member States. The PLS analysis highlighted the roles of adult literacy, urbanization, and population growth, suggesting that social sustainability can be both a function of structural investments, such as infrastructure, and demographic vitality.