The Salutogenic Management of Pedagogic Frailty: A Case of Educational Theory Development Using Concept Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

Academics are experiencing a growing sense of disconnection between their desires to develop students into engaged, disciplined and critical citizens and the activities that appear to count in the enterprise university.(p. 526)

the person may attempt to reduce the amount of information to be dealt with by opting for a simplified belief system which denies the true complexity of the issues involved. Typically this might entail a move towards polarised problem solving with a simplistic yes/no or right/wrong analysis. This diminished judgement can involve an increased personalisation of issues or a hostile egocentricity. In this case the sufferer can only see their limited viewpoint and begins to feel persecuted, interpreting neutral events as being directed at them. Lack of balance is completed by magnification and minimisation whereby trivial are given undue emphasis whilst key factors are played down or ignored. This unsupportable level of cognition eventually leads to fatigue and a state of under-alertness, characterised by forgetfulness, foggy thinking and disorganisation which may be wrongly attributed to a lack of motivation.(p. 20)

2. Pedagogic Frailty and Salutogenesis

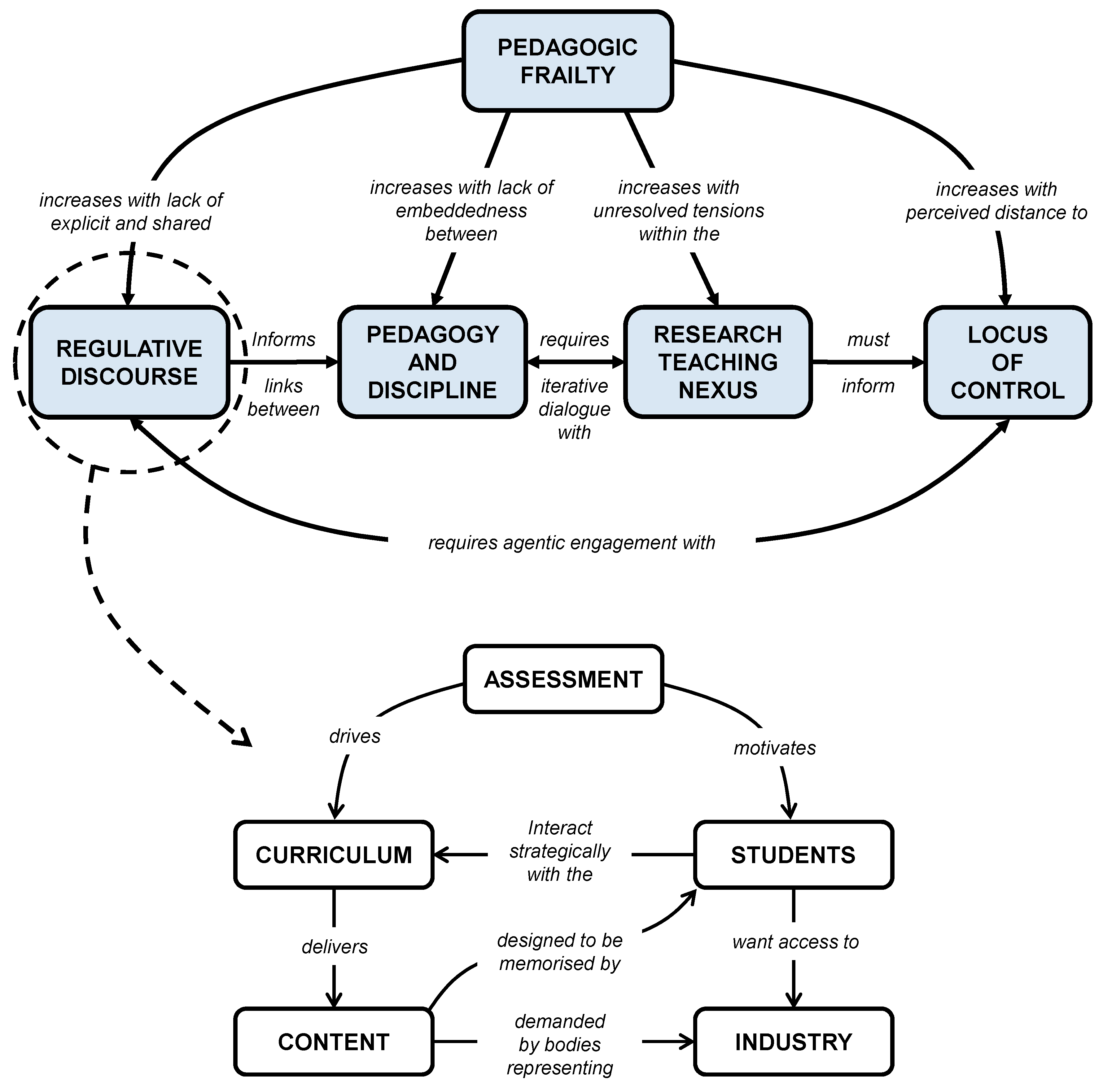

- The nature of the discourse on teaching and learning and whether this concentrates on the mechanisms and procedures of teaching (timetabling, assessments, feedback, etc.) or on the underpinning pedagogy (teacher expectations, professional values, student learning approaches, etc.).

- The relationship between the pedagogy and the discipline and whether teaching offers an authentic insight to the discipline in terms of relating theory and practice.

- How the research within the department relates to the teaching in the department, and how these links are exploited in teaching strategies and made explicit in the programme.

- How the teaching is regulated and evaluated and what appreciation there is of the role of the individual academic in the decision-making processes of the institution.

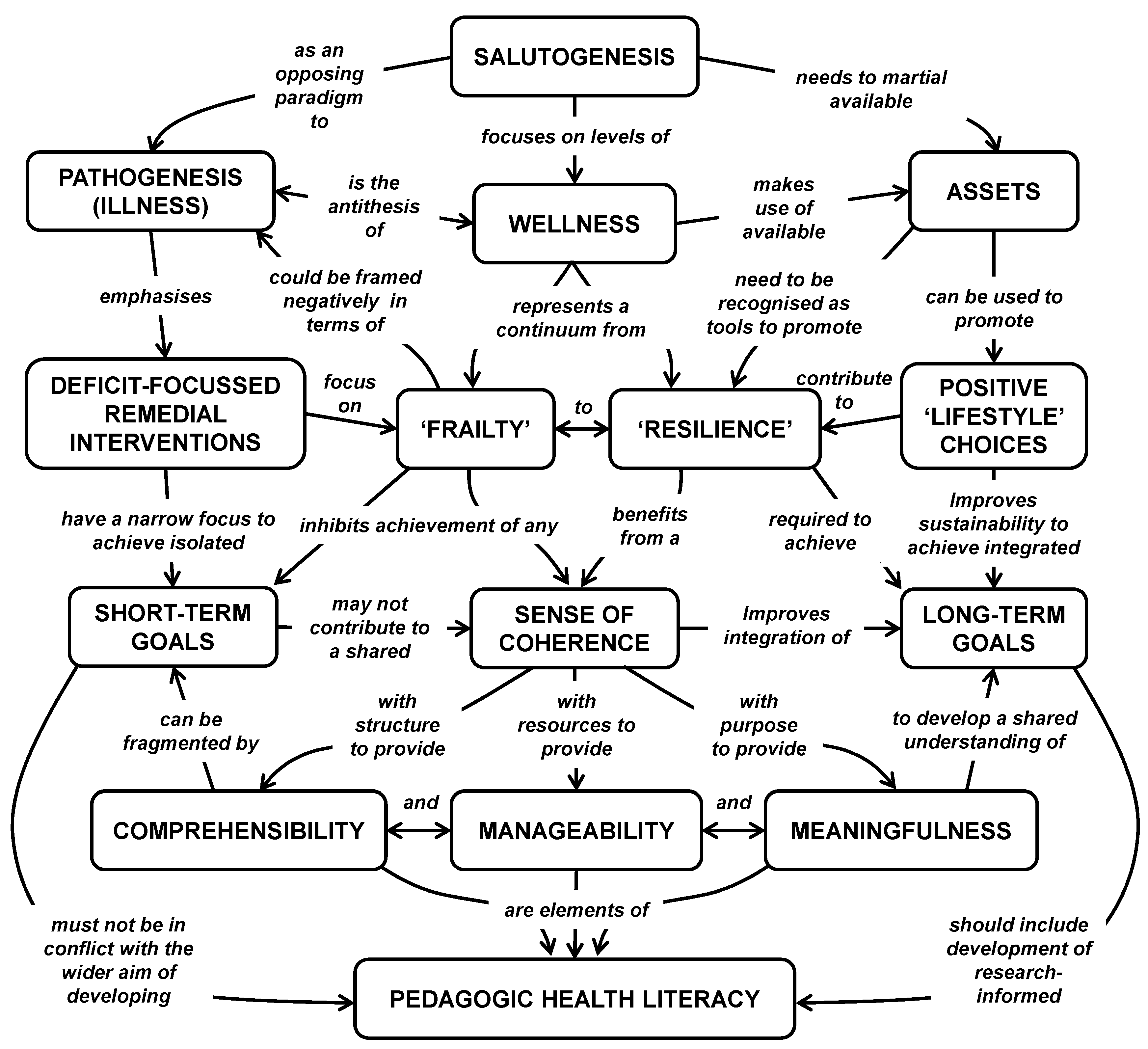

3. Assets

the repertoire of potentials—internal and external strengths qualities in the individual’s possession, both innate and acquired—that mobilise positive health behaviours and optimal health/wellness outcomes.(p. 514)

if we want frailty to be approached as a malleable and preventable condition, a bottom-up approach is needed [and] the tools through which frailty can be managed should come from [participants’] own context and resources.(p. 16)

4. Wellness

A purposeful process of individual growth, integration of experience, and meaningful connections with others, reflecting personally valued goals and strength, and resulting in being well and living values.(p. 48)

5. Sense of Coherence

a global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that:

(1) the stimuli deriving from one’s internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable and explicable (comprehensibility);

(2) the resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by these stimuli (manageability);

(3) these demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement (meaningfulness)(p. 19)

6. Individuals in the System

Superficially, there appeared to be a dichotomy in beliefs about frailty management. On one hand, some policy-makers appeared to support a greater medicalisation of frailty, a need for frailty to be recognised as an authentic clinical issue by medical professionals and treated as such. On the other, there were views that frailty should be demedicalised and that frailty management should be conceived of as an adaptation to life stages and be embraced as a societal issue with ownership devolved to a wider societal network.(p. 4)

7. Benefits of a Salutogenic Gaze towards Pedagogic Health

• Adopts a more affirmative language (pedagogic health literacy) that may be more appealing to senior managers, having a more positive subtext than frailty.

As an analogy, the increased recognition of mental health issues among both university staff and students has moved from a pathological model (dealing with problems after they have arisen) towards one advocating greater awareness of mental health literacy for all. One of the problems of dealing with student wellbeing within the current Higher Education environment is that ‘students approach services when their mental wellbeing is already affecting their ability to cope’ [45]. Rather than wait for problems to surface, it may be better to increase the mental health literacy (MHL) of everyone on campus as students with problems also have the potential to affect others including roommates, classmates and staff [3,46,47,48]. It is, therefore, an issue that affects us all, whatever our own state of mental health. Likewise, before waiting for academics to experience difficulties through frailty within their teaching, moving to the proactive promotion of greater pedagogic health literacy (PHL) across the campus is likely to have a more positive outcome for the institutional community.

• Avoids a potential misuse of the model through adoption of a simplistic harmful binary, the use of which to ‘classify’ staff would in itself be an indicator of prefrailty.

Within the managerial culture of the neoliberal university, there is pressure to find simplistic, instrumental measures that can be adopted for use as performance indicators [49]. The emerging body of work on pedagogic frailty has demonstrated an underpinning complexity to the teaching environment that cannot be adequately represented by a simple metric. This prevents the concept of pedagogic frailty (or pedagogic health) to be subverted for political means and to prevent the disconnections between expectations and practice described by Manathunga et al. [6].

• Indicates a continuum where no system is likely to exhibit ‘total health’ and so creates no arbitrary endpoint to prematurely terminate professional development.

The case studies of academics explored by Kinchin and Winstone [17] concentrate on academics who were already recognised as successful teachers. Therefore, each of them has the potential to contribute to pedagogic resilience within their institution. However, I note again here that individual success is not necessarily an indicator of resilience (rather than frailty) across the system, and that even the most successful teaching teams do not exhibit ‘total health’ (i.e., there is always something new to learn or a new skill to acquire). This depends on developing healthy, positive links between the individuals within a system (e.g., department) for that system to function well.

The learning and development of academics within this perspective do not have a predictable, linear trajectory with an easily defined or predicted endpoint. Rather, ‘[learning] is an entangled, nonlinear, iterative and recursive process, in which [academics] travel in irregular ways through the various landscapes of their experience (university, family, work, social life) and bring those landscapes into relation with each other’ [50]. As such, it resembles the rhizomatic view of learning where knowledge is susceptible to constant modification as it responds to individual or social factors [51].

• The points listed above together help to make utilization of the model more ‘management-friendly’ and from which management activities are not removed.

It is assumed that senior managers may be reluctant to investigate frailty within the systems over which they preside, and of which they are an active part. The pathological model might be seen as a poisoned chalice. Therefore, by looking at pedagogic health, we have a perspective from which we hope senior managers would not feel the need to exclude themselves—something that would invalidate the whole enterprise.

8. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Darabi, M.; Macaskill, A.; Reidy, L. Stress among UK academics: Identifying who copes best. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Smith, A.P. A qualitative study of stress in university staff. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, A.; Farrer, L.; Bennett, K.; Griffiths, K.M. University staff mental health literacy, stigma and their experience of student with mental health problems. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, N.; Price, L. Identity formation among novice academic teachers—A longitudinal study. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, P.; Maton, K. Serving two masters: How vocational educators experience marketisation reforms. J. Voc. Educ. Train. 2019, 71, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manathunga, C.; Selkrig, M.; Sadler, K.; Keamy, K. Rendering the paradoxes and pleasures of academic life: Using images, poetry and drama to speak back to the measured university. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, R. On being transgressive in educational research! An autoethnography of borders. Irish Educ. Stud. 2018, 37, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtsweni, S.H. Salutogenic Functioning Amongst University Administrative Staff; University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, G. Accountability and the rise of ‘play safe’ pedagogical practices. Educ. Train. 2014, 56, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, E.; Harding, T. ‘So I forgot to use 1.5 line spacing! It doesn’t make me a bad nurse!’ The attitudes to and experiences of a group of Norwegian postgraduate nurses to academic writing. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2013, 13, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M. Mapping the terrain of pedagogic frailty. In Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M. Pedagogic frailty: A concept analysis. Knowl. Manag. E Learn. 2017, 9, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Hosein, A.; Medland, E.; Lygo-Baker, S.; Warburton, S.; Gash, D.; Rees, R.; Loughlin, C.; Woods, R.; Price, S.; et al. Mapping the development of a new MA programme in higher education: Comparing private perceptions of a public endeavour. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 41, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Wilkinson, I. A single-case study of carer agency. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M. Visualising Powerful Knowledge to Develop the Expert Student: A Knowledge Structures Perspective on Teaching and Learning at University; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Winstone, N.E. (Eds.) Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Winstone, N.E. (Eds.) Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Alpay, E.; Curtis, K.; Franklin, J.; Rivers, C.; Winstone, N.E. Charting the elements of pedagogic frailty. Educ. Res. 2016, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostromina, S.N.; Gnedykh, D.S.; Ruschack, E.A. Russian university teachers’ ideas about pedagogic frailty. Knowl. Manag. E Learn. 2017, 9, 311–328. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, C.; Gordon, A.L.; Tinker, A. Changing the way “we” view and talk about frailty. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 349–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotegård, A.K.; Moore, S.M.; Fagermoen, M.S.; Ruland, C.M. Health assets: A concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, L.; Kendall, S.; Wills, W. An asset-based approach: An alternative health promotion strategy. Commun. Pract. 2012, 85, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Prom. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Health, Stress and Coping; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I.M. Pedagogic frailty: An initial consideration of aetiology and prognosis. Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the Society for Research into Higher Education (SRHE), Wales, UK, 9–11 December 2015; Available online: https://www.srhe.ac.uk/conference2015/abstracts/0026.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Dooris, M.; Doherty, S.; Orme, J. The application of salutogenesis in universities. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Derham, C. Nursing. In Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood, S. Politics. In Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Whelligan, D. Chemistry. In Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D.P. The Acquisition and Retention of Knowledge: A Cognitive View; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- D’Avanzo, B.; Shaw, R.; Riva, S.; Apostolo, J.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Kurpas, D.; Holland, C. Stakeholders’ views and experiences of care and interventions for addressing frailty and pre-frailty: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180127. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, C.; Franklin, J. Framed autoethnography and pedagogic frailty: A comparative analysis of mediated concept maps. In Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Gkritzali, A.; Morgan, N.; Kinchin, I.M. Pedagogic frailty and conventional wisdom in tourism education. In Proceedings of the 7th International Critical Tourism Studies Conference, Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 25–29 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bonmatí-Tomás, A.; del Carmen Malagón-Aguilera, M.; Bosch-Farré, C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Juvinyà-Canal, D.; Gil, M.D.M.G. Reducing health inequities affecting immigrant women: A qualitative study of their available assets. Glob. Health 2016, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McMahon, S.; Fleury, J. Wellness in older adults: A concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2012, 47, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookfield, S. Pedagogical peculiarities: An introduction. In Pedagogical Peculiarities: Conversations at the Edge of University Teaching and Learning; Medland, E., Watermeyer, R., Hosein, A., Kinchin, I.M., Lygo-Baker, S., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G. Work stressors, health and sense of coherence in UK academic employees. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosein, A.; Rao, N.; Yeh, C.S.-H.; Kinchin, I.M. (Eds.) International Academics’ Teaching Journeys: Personal Narratives of Transitions in Higher Education; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lygo-Baker, S. The role of values in higher education: The fluctuations of pedagogic frailty. In Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Read, B.; Leathwood, C. Tomorrow’s a mystery: Constructions of the future and ‘un/becoming’ amongst ‘early’ and ‘late’ career academics. Int. Stud. Soc. Educ. 2018, 27, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junius-Walker, U.; Onder, G.; Soleymani, D.; Wiese, B.; Albaina, O.; Bernabei, R.; Marzetti, E. The essence of frailty: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis on frailty concepts and definitions. Eur. J. Int. Med. 2018, 56, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwyther, H.; Shaw, R.; Dauden, E.A.J.; D’Avanzo, B.; Kurpas, D.; Bujnowska-Fedak, M.; Holland, C. Understanding frailty: A qualitative study of European healthcare policy-makers’ approaches to frailty screening and management. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. Academic leadership. In Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience in the University; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Broglia, E.; Millings, A.; Barkham, M. Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling services: A survey of UK higher and further education institutions. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2017, 46, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzrow, M.A. The mental health needs of today’s college students: Challenges and recommendations. NASPA J. 2003, 41, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutcher, S.; Wei, Y.; Coniglio, C. Mental health literacy: Past, present and future. Can. J. Psychiatry 2016, 61, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorczynski, P.; Sims-Schouten, W.; Hill, D.; Wilson, J.C. Examining mental health literacy, help seeking behaviours, and mental health outcomes in UK university students. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2017, 12, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J. Re-empowering academics in a corporate culture: An exploration of workload and performativity in a university. High. Educ. 2018, 75, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Harris-Evans, J. Reconceptualising transition to Higher Education with Deleuze and Guattari. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1254–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia; Massumi, B., Ed.; Athlone Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Buta, B.; Leder, D.; Miller, R.; Schoenborn, N.L.; Green, A.R.; Varadham, R. The use of figurative language to describe frailty in older adults. J. Frailty Aging 2018, 7, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Cabot, L.B. Reconsidering the dimensions of expertise: From linear stages towards dual processing. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2010, 8, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, J.G.; Thumser, A.E.; Bailey, S.G.; Trinder, S.L.; Bailey, I.; Evans, D.L.; Kinchin, I.M. Scaffolding a collaborative process through concept mapping: A case study on faculty development. PSU Res. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravett, K.; Yakovchuk, N.; Kinchin, I.M. Enhancing Student-Centred Teaching in Higher Education: The Landscape of Student-Staff Partnerships; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, K.E.; Dwyer, A.; Russell, S.; Enright, E. It is a complicated thing: leaders’ conceptions of students as partners in the neoliberal university. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravett, K.; Kinchin, I.M.; Winstone, N.E. ‘More than customers’: Conceptions of students as partners held by students, staff, and institutional leaders. Stud. High. Educ. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skilbeck, J.K.; Arthur, A.; Seymour, J. Making sense of frailty: An ethnographic study of the experience of older people living with complex health problems. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2018, 13, e12172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravett, K.; Winstone, N.E. ‘Feedback interpreters’: The role of learning development professionals in facilitating university students’ engagement with feedback. Teach. High. Educ. 2018, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L. Learning Development. In Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Medland, E. Academic Development. In Exploring Pedagogic Frailty and Resilience: Case Studies of Academic Narrative; Kinchin, I.M., Winstone, N.E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, M.; Jenkins, A. The role of academic developers in embedding high-impact undergraduate research and inquiry in mainstream higher education: Twenty years’ reflection. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2018, 23, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I.M.; Heron, M.; Hosein, A.; Lygo-Baker, S.N.; Medland, E.; Morley, D.; Winstone, N.E. Researcher-led academic development. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2019, 23, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, W.B. Salutogenesis: The defining concept for a new healthcare system. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2014, 3, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnacle, R.; Dall’Alba, G. Committed to learn: Student engagement and care in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.M.; Glascoff, M.A.; Felts, W.M. Salutogenesis 30 Years Later: Where do we go from here? Glob. J. Health Educ. Promot. 2010, 13, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinchin, I.M. The Salutogenic Management of Pedagogic Frailty: A Case of Educational Theory Development Using Concept Mapping. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020157

Kinchin IM. The Salutogenic Management of Pedagogic Frailty: A Case of Educational Theory Development Using Concept Mapping. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(2):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020157

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinchin, Ian M. 2019. "The Salutogenic Management of Pedagogic Frailty: A Case of Educational Theory Development Using Concept Mapping" Education Sciences 9, no. 2: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020157

APA StyleKinchin, I. M. (2019). The Salutogenic Management of Pedagogic Frailty: A Case of Educational Theory Development Using Concept Mapping. Education Sciences, 9(2), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020157