Abstract

Formulating questions is an integral part of pupils’ learning process and scientific inquiry. Investigating pupil-generated questions in a collaborative science learning setting, combining self-regulation theory and phases of inquiry, can extend the previous research into pupils’ questions. This study considered questions from pupils (n = 24, aged 11–12) as types of interaction to share and reflect on both their own and others’ ideas during a collaborative open inquiry. The study was qualitative in nature. The data was collected by making video recordings of pupils’ team discussions during the study process in 12 science lessons. A content analysis demonstrates that through their questions, the pupils were actively involved in guiding their work from various points of views. These results suggest that fifth graders can successfully conduct a complex open inquiry in teams. Consequently, this study underlines that allowing pupils to work at their own pace, and to take responsibility for their learning, opportunities can arise for pupils to pose questions and regulate their learning through questions.

1. Introduction

Formulating questions is an integral part of pupils’ learning process and their scientific inquiry [1,2,3]. Posing questions either to themselves or to their peers can reveal much about pupils’ interests and the issues that they find problematic [3,4,5]. Since asking questions stimulates pupils to think and communicate with each other, it is important that at school, pupils have opportunities to pose questions. Even though formulating questions is crucial during inquiry, the authors acknowledge that inquiry learning is a challenging process that does not happen automatically see e.g., references [6,7,8].

Most recent studies in science education [8,9] have focused on the characteristics and influence of open inquiry learning. Open inquiry is the most complex level of inquiry [10]. Open inquiry learning offers a high degree of autonomy to pupils and it allows students to select a wide variety of questions and approaches. However, open inquiry does not have to occur without a teacher’s guidance; for example, teachers can scaffold the students’ inquiry process [11].

Generally speaking, during open inquiry lessons, pupils independently plan and conduct the inquiry process, usually in small groups [12]. However, there is still a limited understanding of how pupils engage in social regulation processes, and what roles these regulatory processes play in collaborative open inquiry. Since formulating questions is essential in scientific learning, this study focuses on investigating pupil-generated questions in a collaborative open inquiry setting.

Earlier research has focused on investigating how pupils formulate research questions, collect and record data, and draw conclusions in the context of inquiry learning in science education. However, students’ reflection of inquiry learning is rarely examined [13]. Especially, the regulation of inquiry is not often investigated in the context of collaborative open inquiry. Furthermore, according to our knowledge, in previous research contexts, allowing pupils to take responsibility for making decisions about their learning environment is not generally typical. This means, for example, that the interaction between pupils in teams has not included processes controlling contextual factors, such as deciding where to study in the classroom and selecting learning materials and tools. In this study we want to extend this current way of thinking and investigate pupils’ interaction when they make decisions about their inquiry, the classroom environment and learning materials. In doing so, we are able to see whether pupils can regulate an extremely complex collaborative learning procedure. As stated earlier, formulating questions is an integral part of pupils’ learning process and scientific inquiry [1,2,3]. Therefore, in this study, we investigate pupils’ interaction through questions. Focusing on investigating pupils’ questions, we examine all the questions that the pupils asked during a collaborative open inquiry. We aim to determine the content of pupil-generated questions and whether there are changes in the pupils’ interaction during a collaborative open inquiry. The research questions for this study are the following:

- (1)

- What are the contents of pupil-generated questions in a collaborative open inquiry?

- (2)

- To what extent do the contents of the pupil-generated questions change during a collaborative open inquiry?

- (3)

- What are the similarities and differences in the way pupils pose questions in teams in a collaborative open inquiry?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Socially Shared Regulation of Learning

The focus of this study is to consider pupil-generated questions as a means for regulating social interactions in small teams. The usual way to understand the shared regulation of learning is that it involves independent cyclical phases in the inquiry process [14,15,16]. These phases consist of planning, monitoring, (regulation of) performance, and reflection. Planning relates to the activation of prior knowledge and other processes that occur before task performance [17]. Monitoring involves pupils’ efforts to keep track of their ongoing progress in a learning activity. Regulating performance describes pupils’ actual use and management of learning strategies to reach the intended learning goals. Finally, reflection includes pupils’ meta-level knowledge about the tasks, strategies or themselves. Shared regulation of learning, therefore, presumes situations in which pupils face learning challenges [18]. In challenging situations, pupils can co-regulate the learning process of other pupils who may need assistance, or a pupil can ask a classmate to co-regulate their own learning processes for a specific aspect of the learning task [19,20,21]. In each instance, the regulation process is shared between the pupil and their classmates, and aims to influence the pupil’s cognitive, metacognitive, emotional or motivational and contextual processes to support and guide their and others’ learning [17].

An important reason for investigating pupil-generated questions is that scientific inquiry is rarely a solitary task. Being collaborative or shared in nature, it requires active learning and engagement in joint learning situations and this involves complex interactions in small teams [18]. Therefore, the success of shared regulation depends on each member of a small team, because achieving the final goal is based on mutual support.

2.2. Inquiry Phases

The scientific inquiry is generally divided into smaller, logically connected units that divide the learning process. Each unit includes inquiry activities which are typically related to that specific unit. By dividing scientific inquiry into smaller units, scholars have aimed to reduce the complexity of progression by drawing teachers and pupils’ attention to key features of scientific thinking and self-directed learning [8]. These individual units are referred to as inquiry phases, and their set of connections forms an inquiry cycle [7]. Despite structuring the inquiry into phases, the inquiry cycle is not a prescribed, uniform, linear process; connections between the phases may vary depending on the context.

A scientific inquiry starts usually with some form of orientation which aims to stimulate the pupils’ curiosity and enable them to formulate a research question about a scientific topic of their interest [6,7,8]. Examples of activating pupils’ curiosity include familiarizing pupils with the phases of the inquiry and clarifying to them that they are working the same way as real researchers do [8]. The second phase of inquiry, conceptualization, includes generating research questions in relation to the topics the pupils are curious about [6]. However, pupils do not just formulate questions that fit the topic of the inquiry; they can also differentiate between previously acquired knowledge and remaining questions. Some scholars also stress that during the inquiry, pupils should modify their research questions and revise their problem statements [8]. This illustrates that conceptualization is not merely a one-time step, but rather that it is an ongoing phase.

The investigation phase is the third phase of the inquiry, including planning and conducting the investigation. According to the research approach used, the investigation phase can involve systematic, planned data generation on the basis of a research question, or designing and conducting an experiment in order to test a hypothesis [7]. Conducting a systematic investigation includes planning and recording data in an organized and systematic way. Furthermore, evaluating information and interpreting data are activities in which pupils are involved during the investigation phase. Information gathering requires pupils to constantly understand and evaluate pieces of information, for example by making sense of online information. Interpreting data requires pupils to evaluate data in line with the research questions.

Data interpretation is closely linked to the fourth phase of inquiry, drawing conclusions [8]. The conclusion phase includes planning how to process the results, drawing conclusions, and thinking about why the results were the way they were and how the results match the pupils’ previous experiences. The process of drawing meaning out of the collected data and synthesizing new knowledge illustrates the idea that special attention is needed for pupils to analyze the final outcome of an investigation by interpreting the data [6,7]. The process culminates in drawing a conclusion about the findings of the inquiry.

Presenting and sharing the research results and conclusions of an inquiry with others is also an important phase of the inquiry [6,8]. In this phase there is a focus on communication, involving disseminating the research results and conclusions, and specifying that planning and preparing presentations of all the phases of the inquiry and the outcome is part of the process.

Even though the central basis in many theoretical frameworks is to focus on self-directed learning and metacognition, the regulation of learning by pupils is not usually defined as a separate phase within the inquiry. However, Pedaste et al. (2015) [6] visualize the importance of the reflection and communication phases by linking them clearly to all the other phases of inquiry. This means that the reflection and communication phases interact with all the other phases, and instead of arguing that pupils communicate and reflect on their study process only after completing the inquiry, they claim that pupils discuss their study process while conducting the activities of a specific phase. Thus, pupils use the results of their communication and reflection to revise the activities they engage in during the specific phase, but they can also evaluate the inquiry as a whole.

2.3. Open Inquiry

There are several main aspects to consider in implementing open inquiry methods in primary schools. One is the need to establish a balance between open and guided approaches in terms of who directs the inquiry. In the open approach, pupils engage in conducting an inquiry as a process that they control right from the beginning, participating in the decision-making process of all aspects of the inquiry [10]. In the guided approach, pupils’ inquiry is instead more under the control of their teacher, who deliberately provides help and gives instructions throughout the process [8]. The lowest level of pupil direction occurs in structured inquiry, during which the pupils receive complete instructions from their teacher, leading to a predetermined inquiry process.

The value of an open inquiry approach in which the teacher only scaffolds pupils’ inquiry is not without problems. For example, if the value of open inquiry is evaluated with respect to pupils learning domain-specific knowledge [22] versus how pupils handle their knowledge and skills [23], it is difficult to assess and justify the benefits of the open inquiry approach equally. Furthermore, according to Dorfman et al. (2017) [9], some researchers stress that open inquiry leads to a high cognitive load and thus cannot be effective, while others emphasize that guided inquiry prevents a “waste of time” and reduces pupils’ fears of the unknown. Despite the ongoing debate as to which type of inquiry is more relevant to science education, recent studies have highlighted the need to understand pupils’ ability to regulate their open inquiry in teams, and especially, how students engage in social forms of regulation [21].

Sadeh and Zion (2012) [24] found that students who studied in an open inquiry felt more involved in the project, and felt a greater sense of cooperation with others, in comparison to students who studied in a guided inquiry. Even though an open inquiry can positively affect pupils’ learning, it can be challenging to implement [8,22]. Therefore, since the pupils’ ability to regulate their learning from the social as well as the individualistic perspective are considered important for inquiry [21], the regulation of learning in open inquiry is undoubtedly crucial.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and Context

To study pupils’ questions within an authentic learning situation, we employed a case study design. Case studies are particularly useful in investigating complex, dynamic phenomena as situated in context [25,26,27]. This design was particularly useful in our investigation of pupils’ interaction in small teams. The research was carried out in the Space module, which was designed for fifth-grade pupils (24 pupils aged 11 to 12, with 12 girls and 12 boys) in a rural primary school in eastern Finland. The Space module was designed to fit the school curriculum regarding physics and the school calendar. The module was implemented in 2016 and was taught in twelve 45-min lessons over 12 weeks. The pupils worked in cross-gender teams of four to five. The group composition was arranged so that the teacher selected one member of each team, and as the groups expanded, all members of each team were involved in the selection of the rest of the team.

The goal of the Space module was to engage pupils in the process of self-directed learning in a collaborative science education setting. In practice, the pupils planned, performed and reflected on their learning in teams while conducting an open inquiry in physics. In this study, the pupils had a lot of control over their learning, since they took responsibility for conducting the inquiry and designing their learning environment, and they worked at their own pace. The teacher’s role was to provide a scaffold for the teams and to provide help when pupils asked for it.

In practice, the pupils posed their own questions to investigate the subject, and then located, examined and combined both online and printed information resources to answer their research questions. The learning process required the pupils to negotiate together and make decisions about the methods the group would use. Each team designed their own learning environment, including choosing the working environment (e.g., the classroom, lobby, or library), selected appropriate study materials (e.g., books, notebooks, pens) and equipment (tablet and laptop computers, mobile phones). Furthermore, they also negotiated which software or applications to use during their inquiry. Finally, the pupils planned the exact content of their study according to the idea of open inquiry by negotiating in teams how the information would be shared, how they would all learn, and how the inquiry would be documented. Table 1 summarizes the phases of open inquiry and descriptions of the activities in each lesson.

Table 1.

Descriptions of pupils’ work and the teacher’s scaffolding in each lesson and phase of inquiry.

The communication and reflection were designed to continuously create links between the phases of the inquiry. From the beginning of the module the pupils discussed their choices in teams: e.g., why they chose to use certain learning materials or to do certain activities. The space theme was also integrated during these 12 weeks with the lessons in Finnish language and literature, and the visual arts. In these lessons, the pupils read texts about space, completed learning activities, and, using process writing techniques in a computer environment, wrote their own texts and designed cover pages for their texts.

3.2. Data Collection

All the team discussions were video recorded during the module. Video data was collected by equipping one pupil in each team with a head-mounted camera (GoPro). Although only one pupil had the camera, the camera recorded the whole team during the lessons. The team decided who would wear the camera, and they could also swap it around during the lessons. Five head-mounted cameras were used simultaneously in the lessons. The recorded material amounted to 2250 min of video data, out of which 1260 min was analyzed and transcribed in full, as one lesson and one team were excluded for technical reasons. Furthermore, the first two lessons and the final lesson of the Space module were intentionally left out, since the pupils were not working in teams or planning their learning environment during these lessons. Altogether, the transcribed data consisted of 144,388 words.

3.3. Analysis

Interaction during the collaborative open inquiry lessons were analyzed by developing a coding scheme to categorize the content of all the questions posed by pupils. Furthermore, changes in interaction were analyzed by calculating the frequency of question contents during collaborative open inquiry. Finally, similarities and differences in the way pupils interacted in teams were analyzed by calculating the numbers of questions and the content of the questions in each team.

In more detail, the analysis of the question content consisted of two independent rounds. Firstly, a coding scheme was iteratively developed to structure the content of the pupils’ questions based on two randomly selected team discussions. A data-driven content analysis technique was applied, which included open coding, creating categories, and abstraction steps [28,29]. The selected coding unit for analysis was an interrogative or rhetorical question posed by one pupil. During the open coding phase, notes were written on each question to describe the content of the question. The notes were subsequently collated, and initial codes were generated keeping in mind the phases of inquiry and principles of self-directed learning theory. In creating categories, the lists of initial codes were grouped under higher order categories to reduce the number of codes. Formulating the higher order categories took place by collapsing initial codes that were similar or dissimilar and classifying them as ‘belonging’ and ‘not belonging’ to the same broader higher order category. In the abstraction step, final categories in terms of combining self-directed learning theory and phases of inquiry were formulated. Categories were named using content-characteristic words by grouping them into subcategories, which in turn were grouped into generic and main categories.

Secondly, all the questions using the coding schema created in the previous round were analyzed. The number of questions was counted, and they were arranged according to the coding scheme and teams. Relative percentages of the frequencies of the questions were established within each team as well. Since the sequence of the inquiry phases was not straightforward [7], the pupil-generated questions were organized and split into three sets, keeping in mind that the pupils designed their learning environment from lesson 3 to 11 (see Table 1). Therefore, lessons 3–5 were considered the beginning phase of the open inquiry, as the pupils started to work in teams and also began to design their learning environment. Lessons 7–8 produced the middle phase of the open inquiry, since lesson 6 was left out of the analysis for technical reasons. Lessons 9–11 constitute the end phase of the inquiry, since in lesson 12 the pupils did not design their learning environment and all teams gave their presentations at the front of the classroom.

The first two authors created the coding scheme. However, in order to prove the analysis and to agree on question descriptions, exact concepts and meanings, different versions of the coding scheme were compared and discussed three times during the analysis together by three authors. The fourth author of this paper was the class teacher and so knew the pupils very well. Therefore, in order to verify the result results, she did not take part in analysis of the data.

4. Results

4.1. Content of the Pupil-Generated Questions

The first research question focused on investigating the contents of the pupil-generated questions during the collaborative open inquiry lessons. The question contents (see Table 2) related to five main areas: coordinating teamwork, conducting the investigation, organizing resources, organizing software use and questions unrelated to the inquiry. The content of the teamwork coordination area included questions on taking, sharing and monitoring responsibilities by revising the scientific research topic, taking turns performing inquiry activities and ensuring that team was carrying out the inquiry. The content of conducting the investigation involved questions about planning and performing data retrieval and data interpretation. Preparing how to present the inquiry for others also formed the content of these questions. Arranging the physical learning environment and problems using the learning materials formed the content of the questions related to organizing resources. Organizing software use, in turn, included questions related to selecting which software to use for inquiry and problems in using it. The content of the questions not related to the inquiry involved questions about hobbies, music, TV shows, friends, families and life in general.

Table 2.

Content and the number of pupil-generated questions in the collaborative open inquiry.

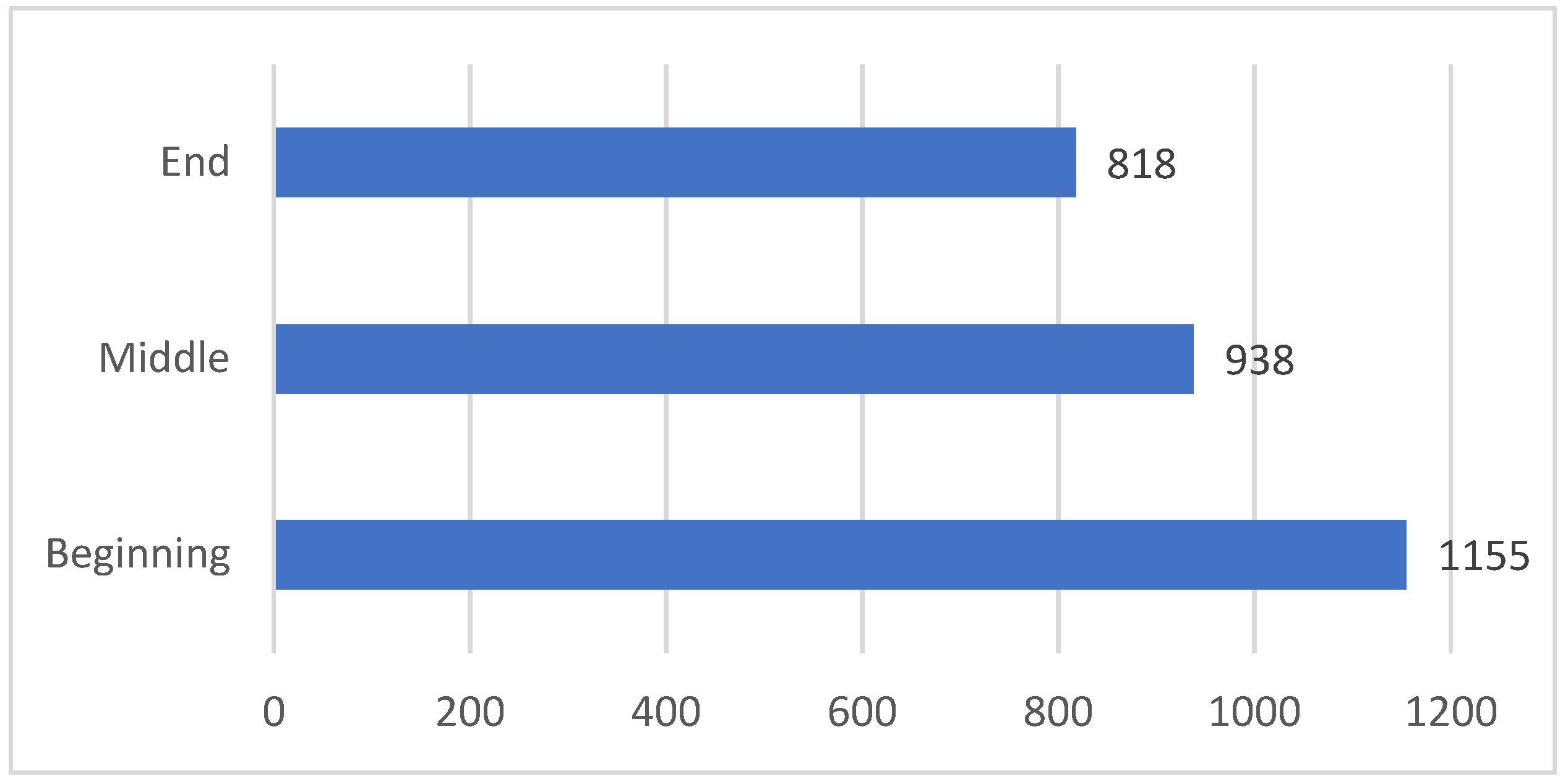

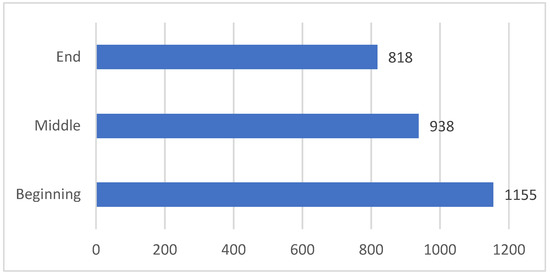

4.2. Frequency of the Question Contents During the Collaborative Open Inquiry

The second research question was related to investigating to what extent the contents of the pupil-generated questions changed during the collaborative open inquiry. The total number of questions the pupils asked in teams was 2911 (Table 2). The most common question content was related to conducting the investigation (n = 1004) and fewest questions concerned organizing the use of software (n = 281). The pupils asked 1155 altogether questions near the beginning of the inquiry, 938 in the middle, and 818 towards the end of the process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The number of questions at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the collaborative open inquiry.

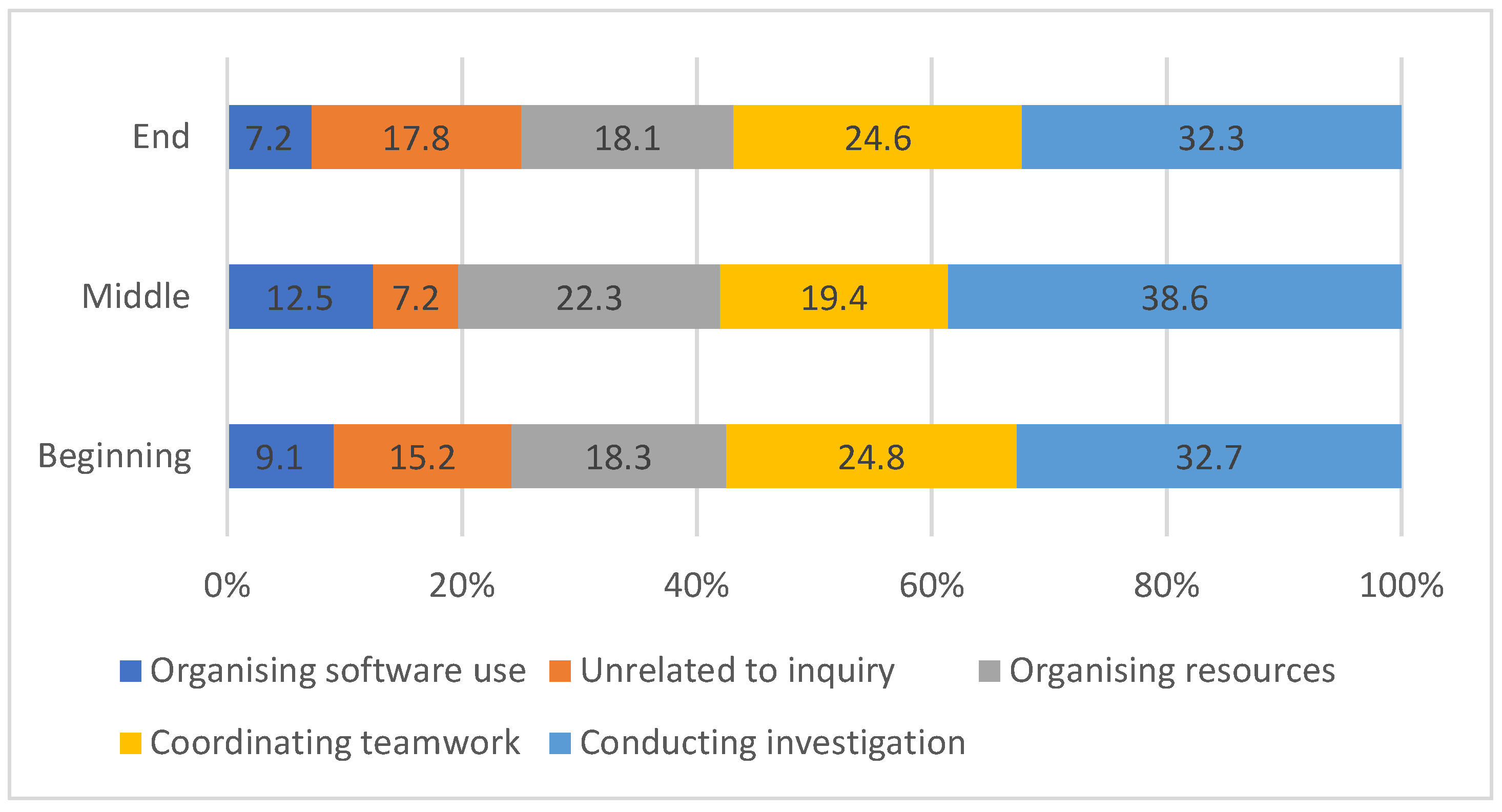

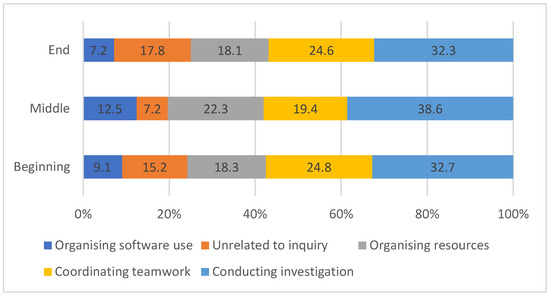

The relative percentages of the question contents at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the collaborative open inquiry process show that there are similarities and differences between lessons (Figure 2). When comparing the beginning, middle and end lessons, there was some similarity in the number of questions concerning conducting investigation in the lessons since it was the most frequent content area of the questions throughout the inquiry. The middle lessons of the inquiry differed most from the other lessons. The least frequent questions in the middle phase were those that were not about the inquiry. The difference between the lessons was significant since these questions are 8 percent more common at the beginning than in the middle, and 10.6 percent higher at the end than in the middle. It is also notable that the frequency of questions related to conducting the investigation, organizing resources and software use were highest in the middle lessons, while questions related to coordinating teamwork were at their lowest.

Figure 2.

Relative percentages of the types of question contents at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the collaborative open inquiry.

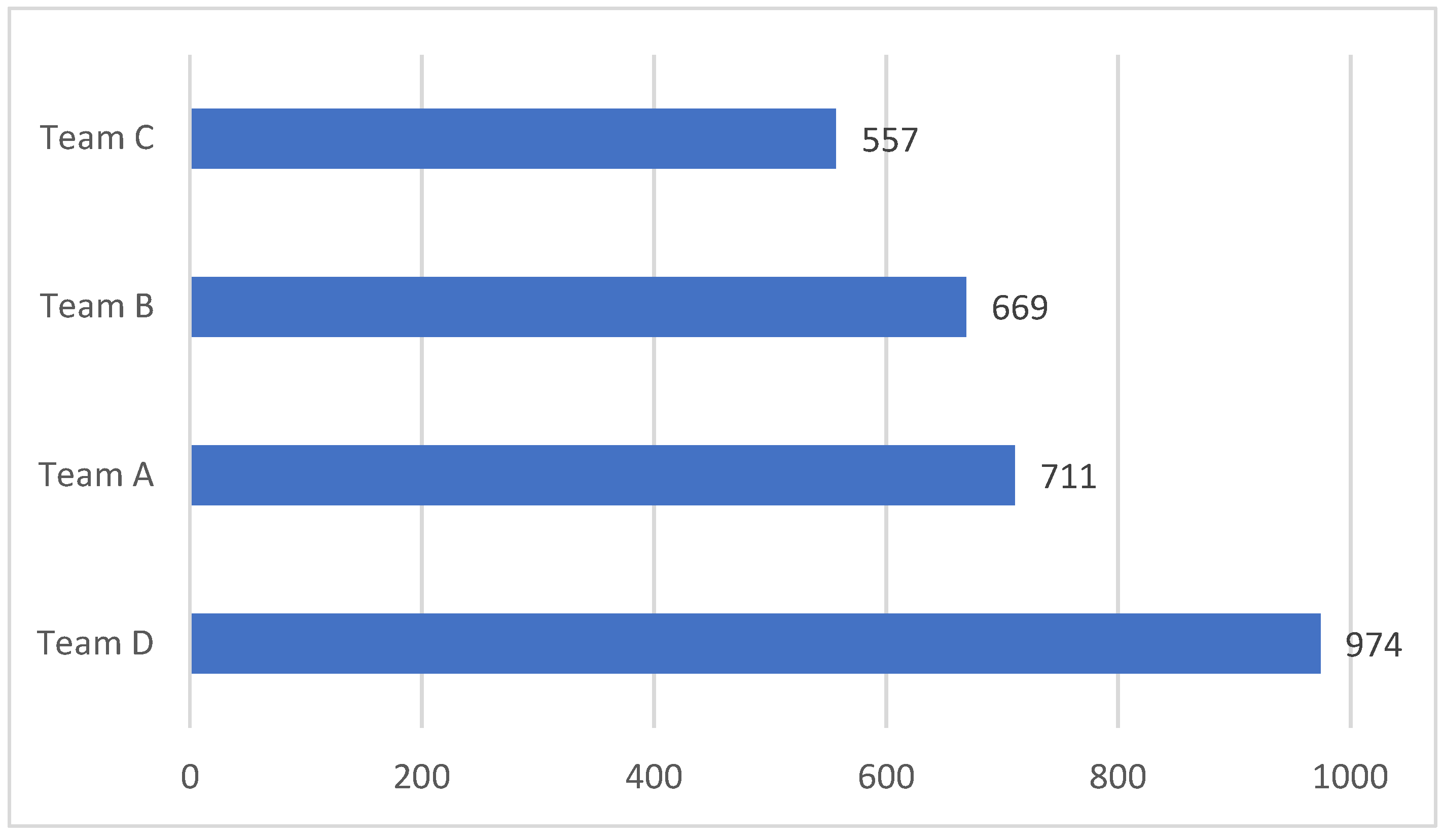

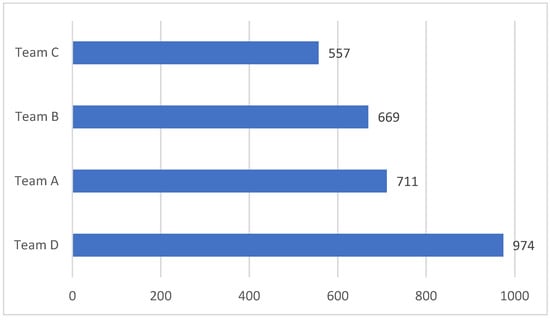

4.3. Questions by the Teams

The third research question considered what the similarities and differences were in the way the pupils posed questions in teams during the collaborative open inquiry lessons. The number of questions varied between the teams (Figure 3). The difference between the most and least active teams was 417 questions: in Team D, the pupils asked 974 questions, while pupils in Team C generated 557 questions. The difference between the first and the second most active teams was notable, since in Team D pupils asked 263 more questions compared to Team A. However, the difference between the second and third most active Team A and Team B was low and amounted to only 42 questions.

Figure 3.

The number of questions by team.

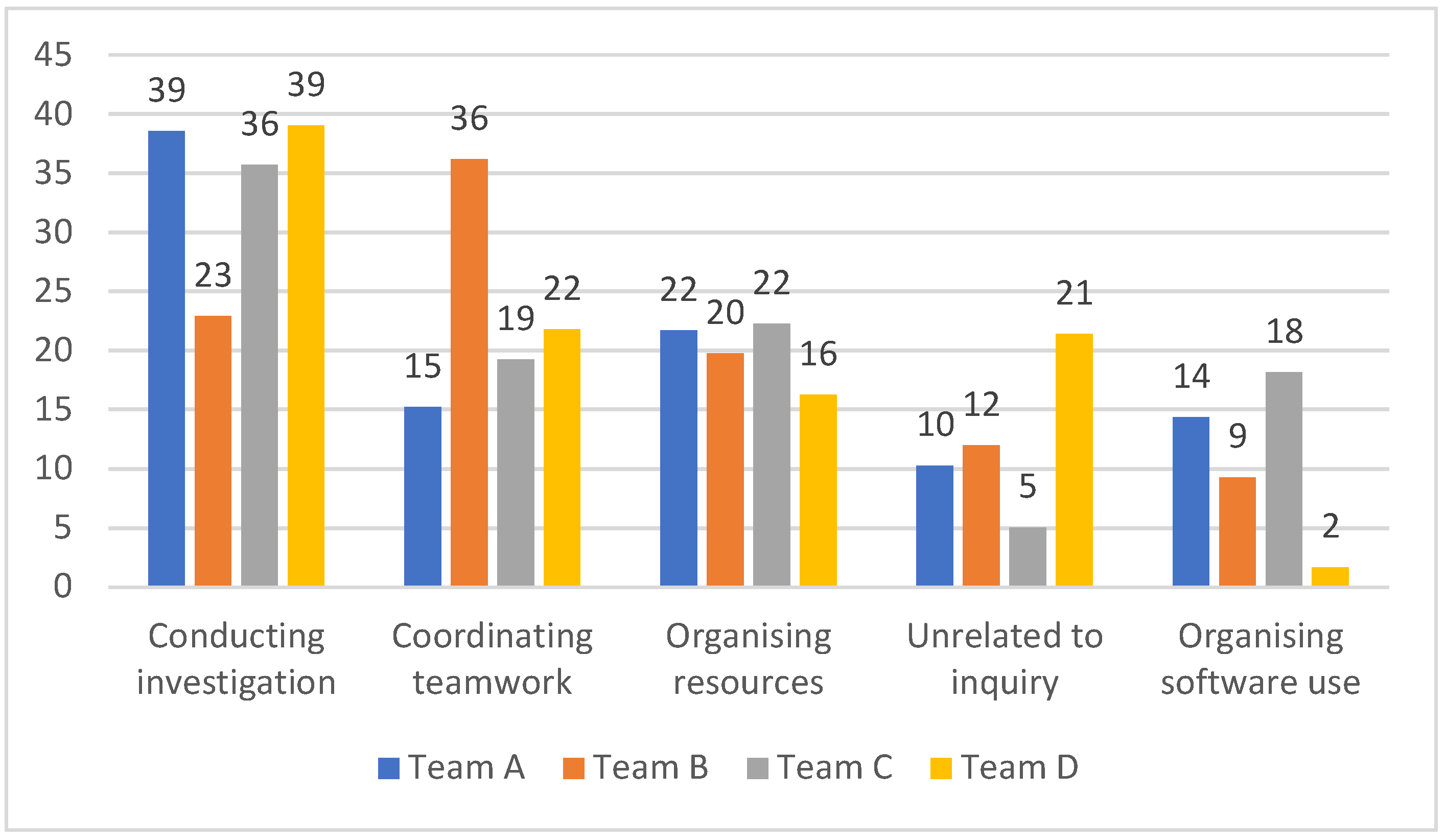

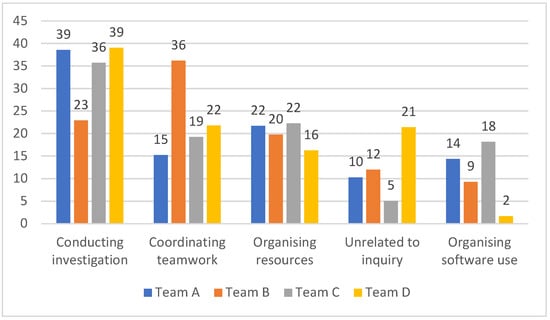

There were differences between the teams regarding the content of the questions they asked as well (Figure 4). Comparing the relative percentages of questions asked in teams reveals that Team B asked a smaller proportion of questions concerning conducting the investigation than the other teams. Instead, Teams A, C and D asked nearly the same number of questions linked to conducting the investigation. Team B also differed from the other teams in the number of questions they asked about coordinating teamwork. In Team B, taking, sharing and monitoring responsibility were the most frequent types of question by far: 36 percent of all Team B’s questions were about coordinating teamwork. It is also notable that in Team A, only 15 percent of the questions were about coordinating teamwork.

Figure 4.

Relative percentages of the question content for each team.

There are only minor distinctions between the teams in terms of the questions regarding organizing resources. Team D was less active with this type of question content, but the difference between Team D and the most active teams was only 6 percent. In practice, Teams A, B and C were equally active in asking questions about controlling resources, since 22 percent of Team A’s questions and 20 percent of Team C’s questions were linked to this content.

The teams differed when it came to questions which were unrelated to the inquiry. Pupils in Team D asked these questions more frequently than the other three teams. The relative percentage of questions that were not related to the study content was 21 percent in Team D and only 5 percent in Team C. Teams A and B asked nearly equal numbers of questions of this type, since 10 percent of Team A’s and 12 percent of Team B’s questions were related to topics which were unrelated to the inquiry.

The teams did not ask questions about organizing the use of software equally actively. Team C was the most active in asking these sorts of questions: 18 percent of their questions were linked to this content, compared to only 2 percent of Team D’s. There were also differences between Teams A and B in these questions: questions about software use made up 14 percent of Team A’s questions and 9 percent of Team B’s questions.

5. Discussion

Inquiry in small teams requires interdependence between leaners to achieve mutual goals, and collective responsibility concerning any difficulties encountered during learning activities [30]. Our results show that by using questions, the shared regulation of the open inquiry occurred as the pupils searched for answers on how to (1) organize teamwork, (2) conduct the investigation, and (3) organize resources and software. These questions were related to planning, performing and monitoring the inquiry, and arranging and using the learning environment in which the inquiry occurred. In addition to questions related to the inquiry, the pupils also asked questions which were unrelated to the immediate learning event.

Our study also shows that the contents of questions shifted during the phases of the inquiry, but there were also similarities between the phases. The middle phase of inquiry seems to be the most intensive time for learning science content including pointing out the role of contextual aspects as well. This included versatile and rich participatory strategies that were likely to support a joint understanding of ideas, not only in conducting the investigation, but also setting up the learning environment in which the inquiry took place. Thus, the pupils also monitored their ongoing inquiry performance from wider contextual perspectives, but those perspectives were closely related to clarifying the contextual conditions of inquiry learning.

Despite conducting the investigation and the contextual aspects playing an important role in the middle phase, these elements also played a continuous role for all the teams and stimulated them to pose questions throughout the inquiry. By asking questions related to conducting the investigation the pupils maintained a continuous inquiry [8] and did not answer the research questions “immediately” but linked them to the required data collection activities. As interpreting information is a sign of critical thinking [31], the questions related to conducting the investigation demonstrated the pupils’ strategies to constantly share their data retrieval, data interpretation and dissemination strategies in a wide sense. It is evident that the questions linked to conducting the investigation demonstrate that the pupils were aware or became aware that there were different ways to search for information, and the difficulties inherent to searching and interpreting information, as well as the challenges of sharing the data. These all are important inquiry actions and illustrate the pupils’ engagement in performing important scientific working activities [7].

On the one hand, the questions concerning organizing resources seem to imply that arranging the learning environment contained aspects that were presumably unfamiliar to the pupils, but on the other hand, illustrate that the pupils were eager to plan their learning environment. Since the pupils in our study studied in different places (e.g., in the classroom, lobby or library), the physical distance between the teacher and the pupils might partly explain why the flexibility in choosing the learning space also invoked cognitive regulation within the teams: the pupils asked each other for help in using the learning materials and equipment. Our results are in line with earlier studies [32] that have found that changes to learning in flexible spaces demonstrate that the physical classroom environment facilitates self-regulation and collaboration. Since the questions focused on organizing resources and software were at their highest in the middle phase of the inquiry but fairly evenly distributed throughout inquiry process, our study suggests that leaving more freedom to the learners to structure the learning environment could also promote their engagement in the inquiry phases.

The teams differed from each other in terms of how actively they posed questions and which question contents were typical for each team. The team interaction tended to be of two types: that which focused on the task the team was dealing with, and that which sustained, strengthened or awoke interpersonal relationships within team [33]. Our study showed that the open inquiry provided a context wherein the pupils create norms for collective responsibility and checked whether the participants had a shared understanding of how the team could remain focused on the task [34]. However, monitoring responsibilities and taking turns might be more important in some teams than conducting the investigation (see Figure 4). Focusing especially on each members’ responsibilities and the turn taking illustrate that the team members were more often determining what the members were doing than negotiating a synthesis of ideas related to understanding the goals of the inquiry itself. There may be several reasons which are likely to explain this. Ucan and Webb (2015) [21] found that student groups often activated shared emotional and motivational regulation processes when they experienced a variety of socially challenging situations. This included having different priorities in relation to the task, failing to reach a consensus over a shared understanding, or exhibiting disruptive behavior during a group activity. Since in this study it was not captured why the pupils posed questions or who posed them, it remains unclear whether coordinating teamwork questions demonstrate socially challenging situations within the team. It remains also unclear if the team members equally actively asked questions about mutual responsibilities or whether they were under one member’s control. In any case, our study shows that pupils related coordinating teamwork and conducting investigation activities closely to each other. This suggests that reflection in an inquiry includes not only how to conduct inquiry activities successfully [7], but also how to maintain the team’s shared engagement in relation to carrying out their task [19].

Questions about the use of software illustrated that the pupils considered alternative software to use in the inquiry and sought help in using software for task-related purposes. This result supports earlier findings that computer environments trigger pupils to seek help [35], but did not show any attempts by the pupils to use software collaboratively for specific inquiry activities. Previous research has shown that digital tools may also promote self-regulated learning from motivational perspectives [36]. However, our results do not fully support this argument. Even though our results show that the pupils planned which digital tools they wanted to use and asked for help when they encountered problems using them, they did not generate questions to consider interesting alternatives, or demonstrate that selecting and using digital tools was enjoyable and satisfying. Instead, our results confirmed that digital tools encouraged the pupils to consider their thinking strategies by identifying and correcting mistakes in using digital platforms [37]. Focusing on identifying and correcting mistakes might tell us that the pupils in our study were not familiar with the software they chose to use in a technical sense. Furthermore, since organizing the use of software did not get much of the pupils’ attention and one team posed very few of these questions, it may be because they relied more on printed materials in the inquiry. Another explanation might be that the actual software use was easy for them, or that it was not shared but under the control of pupils who could use the software skillfully and did not need help. The most promising explanation for the low number of questions related to organizing the use of software is, however, that the pupils might have had difficulties linking the use of software to their collaborative inquiry. The content of the questions concerning the use of software did not explain in detail which inquiry activities triggered the pupils to pose these questions. Instead, it can be argued that while using questions, the pupils did not negotiate software use to conduct data retrieval, data selection and data recording activities. The only exception which illustrated pupils’ attempts to make links between software use and inquiry phases was scientific writing. However, planning and preparing presentations in this study was understood as a part of conducting investigation questions, not as separate question content.

The questions which were unrelated to the inquiry showed that the pupils did not only ask task-related questions. Asking these sorts of questions can be interpreted as a sign of creating a positive team climate for collaboration, or these questions could tell us that the teams were too socially active during their collaboration [38] or not interested in the inquiry. In many studies, these kinds of off-task activities are considered to have a deleterious effect on learning and performance [39,40], and negative relationships between social activities and team performance have been found [38]. However, since the number of off-task questions were relatively low in three teams (Figure 4), and suggestively high only in one team, it can be suggested that by asking questions which were unrelated to the inquiry the pupils aimed to show that they needed a break from the complex inquiry. Furthermore, since the team which most actively asked questions which were unrelated to the inquiry were also the team who asked the most questions related to conducting the investigation, the use of off-task questions indicates more a rather positive than negative interaction between the team members.

Especially from the perspective of the phases of inquiry, making sense of the constraints of the inquiry in general is missing from the pupils’ questions. This finding resonates with related research on how individuals interpret their own inquiry experiences [41], which finds that even adults can complete an inquiry as a set of stepwise procedures without considering how knowledge is created in science. Even though the pupils in our study did not visibly pose questions about how and why knowledge is created through the phases of inquiry, asking questions as a whole suggests they follow the phases of open inquiry by planning and conducting data retrieval and interpretation activities, as well as planning and preparing the dissemination of the results.

Despite the fact that this research did not examine whether the question strategies facilitated the construction of any new scientific understanding, our results support the idea that pupils’ awareness of the significance of the phases of an open inquiry requires special attention in low-structured classroom conditions [35]. The explanation may be that pupils need time to learn how to learn through the phases of an open inquiry in order to strengthen their understanding of the phases of scientific inquiry [8,42]. In particular, a lack of awareness among the pupils of the precise purpose of the phases of open inquiry may explain why, in our study, not all the core aims of each phase of the inquiry were fulfilled. For example, reformulating research questions and drawing conclusions did not emerge as a significant type of pupil-generated question. Instead, asking questions related to conducting the investigation revealed that the open inquiry triggered pupils to evaluate and interpret pieces of information throughout the process. Evaluating and interpreting pieces of information itself is a positive result, but analyzing the final outcome of the investigation and the learning process as a whole are examples of the core content of the inquiry as well [6,7]. Since these important types of question were not captured in our study, it remains unclear whether pupils became aware of the wider picture of open inquiry through the questions posed during their inquiry.

There are certain limitations to consider in our study. Firstly, it is important to address the context of the study. The Space module was planned and implemented in collaboration with the first and fourth author of this paper, and altogether 24 pupils participated in our study. However, this study was constructed in an authentic school context as a part of the normal schoolwork. To increase the internal validity and authenticity of this study, the context was emphasized, and the study design was set in the terms of the context in which the study was conducted. To validate our findings, we recommend future research to further investigate other open inquiry projects in primary schools.

Second, the way team discussions were recorded must be considered. Since we analyzed videos captured with GoPro cameras, it is likely that we did not observe all the pupils’ questions that were raised when some pupils were too far away from the camera. Another consideration regarding video recordings is that since the teams did not start to work together at the very beginning of the project, the first two lessons of the Space module were not recorded. For future research, we advise recording the pupils’ discussions from the very beginning of open inquiry process. Nevertheless, similarities between different teams show that the recorded videos sufficiently represent the pupil-generated questions. Furthermore, in this study, it was possible to use research triangulation to increase the credibility and validity of research. However, for future research, we recommend capturing all the pupils’ actions on camera.

6. Conclusions

This study showed that when investigating pupil-generated questions in a collaborative science learning setting, combining self-regulation theory and the phases of inquiry can extend the earlier understanding of pupils’ questions. By investigating pupil-generated questions, it seems to be possible to gain insight into the pupil’s interaction and how they regulate a collaborative open inquiry. Thus, an inquiry in small teams can create a challenging—but also beneficial platform for pupils to activate their own, and shared, problem exploration and participation. During a collaborative open inquiry, the teacher needs to adapt her/his instruction to the pupils’ needs and provide individual help when pupils have difficulties understanding the topic or task.

Young learners can conduct a collaborative open inquiry, even if conducting collaborative open inquiries in primary schools is not common. The integration of the space theme with subjects other than physics during the open inquiry might have facilitated the pupils’ engagement in an extended science topic. Therefore, further studies to focus more on the effect of the classroom learning culture on pupil-generated questions are required. Allowing pupils to design their entire learning environment could be very motivating, since the pupils consistently and regularly shared their ideas about organizing resources. However, making links between software use and collaborative open inquiry seems to be a challenging task for the pupils. Therefore, future research to investigate the reasons for the pupil-generated questions, especially from the software use perspective, is required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., S.K., K.P. and S.R.-Z.; Formal analysis, S.P., S.K. and K.P.; Investigation, S.P. and S.R.-Z.; Writing—original draft, S.P. and S.K.; Writing—review & editing, K.P. and S.R.-Z.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Biddulph, F.; Symington, D.; Osborne, R. The place of children’s questions in primary science education. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 1986, 4, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.; Brown, D.E. Student-generated questions: A meaningful aspect of learning in science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2002, 24, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. Teaching scientific practices: Meeting the challenge of change. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.; Osborne, J. Supporting argumentation through students’ questions: Case studies in science classrooms. J. Learn. Sci. 2010, 19, 230–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, D. Do students need to be taught how to reason? Educ. Res. Rev. 2009, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.Y.; Frederiksen, J.R. Inquiry, modeling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cogn. Instr. 1998, 1, 3–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedaste, M.; Mäeots, M.; Siiman, L.A.; De Jong, T.; Van Riesen, S.A.; Kamp, E.T.; Tsourlidaki, E. Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 14, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Uum, M.S.; Verhoeff, R.P.; Peeters, M. Inquiry-based science education: Scaffolding pupils’ self-directed learning in open inquiry. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 2461–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, B.S.; Issachar, H.; Zion, M. Yesterday’s Students in Today’s World—Open and Guided Inquiry Through the Eyes of Graduated High School Biology Students. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion, M.; Mendelovici, R. Moving from structured to open inquiry: Challenges and limits. Sci. Educ. Int. 2012, 23, 383–399. [Google Scholar]

- Zion, M.; Cohen, S.; Amir, R. The spectrum of dynamic inquiry teaching practices. Res. Sci. Educ. 2007, 37, 423–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvánková, P.; Popjaková, D. How to link geography, cross-cultural approach and inquiry in science education at the primary schools. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2018, 40, 707–722. [Google Scholar]

- Runnel, M.I.; Pedaste, M.; Leijen, Ä. Model for guiding reflection in the context of inquiry-based science education. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2013, 12, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P.R. A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winne, P.H.; Hadwin, A.F. The weave of motivation and self-regulated learning. Motiv. Self-Regul. Learn. Theory Res. Appl. 2008, 12, 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S.; Järvenoja, H.; Malmberg, J.; Isohätälä, J.; Sobocinski, M. How do types of interaction and phases of self-regulated learning set a stage for collaborative engagement? Learn. Instr. 2016, 43, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, P.; Järvelä, S.; Mäkitalo-Siegl, K.; Ahonen, A.; Näykki, P.; Valtonen, T. Preparing teacher-students for twenty-first-century learning practices (PREP 21): A framework for enhancing collaborative problem-solving and strategic learning skills. Teach. Teach. 2017, 23, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiskala, T.; Vauras, M.; Lehtinen, E.; Salonen, P. Socially shared metacognition of dyads of pupils in collaborative mathematical problem-solving processes. Learn. Instr. 2011, 21, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A.; Järvelä, S.; Miller, M. Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Zimmerman, B., Schunk, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ucan, S.; Webb, M. Social regulation of learning during collaborative inquiry learning in science: How does it emerge and what are its functions? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2503–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Keinonen, T. The effect of student-centered approaches on students’ interest and achievement in science: Relevant topic-based, open and guided inquiry-based, and discussion-based approaches. Res. Sci. Educ. 2017, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.A.R.; Bergendahl, V.C.B.; Lundberg, B.; Tibell, L. Benefiting from an open-ended experiment? A comparison of attitudes to, and outcomes of, an expository versus an open-inquiry version of the same experiment. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2003, 25, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, I.; Zion, M. Which type of inquiry project do high school biology students prefer: Open or guided? Res. Sci. Educ. 2012, 42, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.L. Investigating self-regulated learning using in-depth case studies. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Zimmerman, B.J., Schunk, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 346–360. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research; Sage UK: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage UK: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative content analysis! In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Flick, U., Ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2014; pp. 170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenszayn, R.; Assaraf, O.B.Z. When collaborative learning meets nature: Collaborative learning as a meaningful learning tool in the ecology inquiry based project. Res. Sci. Educ. 2011, 41, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Crippen, K.J.; Hartley, K. Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Res. Sci. Educ. 2006, 36, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariippanon, K.E.; Cliff, D.P.; Lancaster, S.L.; Okely, A.D.; Parrish, A.M. Perceived interplay between flexible learning spaces and teaching, learning and student wellbeing. Learn. Environ. Res. 2017, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Group Dynamics; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hmelo-Silver, C.E.; Barrows, H.S. Facilitating collaborative knowledge building. Cogn. Instr. 2008, 26, 48–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkitalo-Siegl, K.; Kohnle, C.; Fischer, F. Computer-supported collaborative inquiry learning and classroom scripts: Effects on help-seeking processes and learning outcomes. Learn. Instr. 2011, 21, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, M.P.; Hartmeyer, R.; Bentsen, P. Systematically reviewing the potential of concept mapping technologies to promote self-regulated learning in primary and secondary science education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.C.; Hu, S.C. Applying computerized concept maps in guiding pupils to reason and solve mathematical problems: The design rationale and effect. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2013, 49, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Erkens, G.; Kirschner, P.A.; Kanselaar, G. Task-related and social regulation during online collaborative learning. Metacogn. Learn. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.D.; Schnackenberg, H.L. Effects of informal cooperative learning and the affiliation motive on achievement, attitude, and student interactions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.M. Adapting teacher interventions to student needs during cooperative learning: How to improve student problem solving and time on-task. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2004, 41, 365–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windschitl, M. Inquiry projects in science teacher education: What can investigative experiences reveal about teacher thinking and eventual classroom practice? Sci. Educ. 2003, 87, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.K.; Hsieh, C.E. Developing sixth graders’ inquiry skills to construct explanations in inquiry-based learning environments. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 28, 1289–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).