A Narrative Review on Augmented Reality in Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Approach

3. Exploring the Basics of Augmented Reality

3.1. Definitions and Differences Between Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Mixed Reality

3.2. Origins and Evolution

4. Key Hardware Elements and Different Types of AR Systems

4.1. Displays

4.2. Tracking Systems

- Image-based AR: includes marker-based and markerless solutions that use image recognition techniques to track an object and its position.

- Location-based AR: uses position data to identify an object and its position (Cheng & Tsai, 2013; Koutromanos et al., 2015).

4.3. Input Devices

4.4. Computer

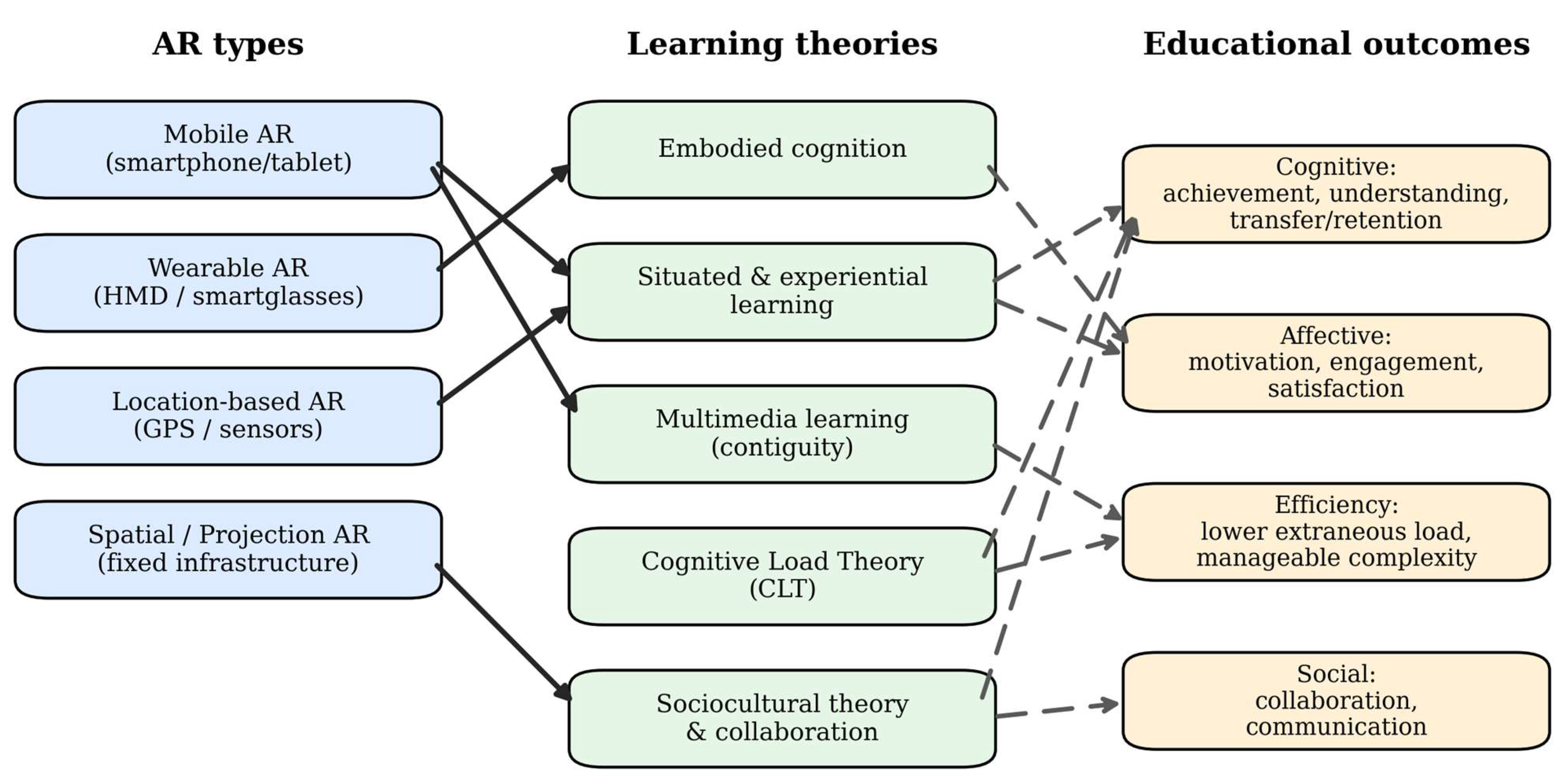

5. Augmented Reality, Education, and Theories of Learning

5.1. From Embodied Interaction to Embodied Cognition

5.2. Situated Learning, Experiential Learning, and the Contiguity Principle of Multimedia Learning

- -

- Case Study: Santos et al. explored AR applications for situated vocabulary learning, leveraging multimedia learning theory to design an AR system for handheld devices (Santos et al., 2016). Their study focused on developing and evaluating AR applications for learning Filipino and German vocabulary in authentic contexts. The AR system allowed users to interact with virtual content, including text, images, audio, and animations, superimposed onto the real environment. Compared to non-AR methods, AR-supported learning improved vocabulary retention and enhanced motivation, attention, and satisfaction (Santos et al., 2016). This case study highlights a key boundary condition: situated vocabulary gains are more likely when AR cues closely match the learner’s perceptual context and multimedia elements are integrated to minimize split attention.

- -

- Case Study: Wu and Huang investigated the application of AR in an interactive design course to foster experiential and situated learning (C. Wu & Huang, 2020). Their study involved 62 university students divided into 17 groups tasked with designing AR applications. The course was structured around key activities, including case analysis, project planning, peer reviews, and performance presentations. Grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning theory and the situated learning model, the instructional design emphasized real-world contexts and collaboration. Results revealed that 15 of 17 groups successfully integrated AR technology with prior knowledge, creating applications such as games and educational tools. Students reported improved creativity, teamwork, and understanding of AR technologies (C. Wu & Huang, 2020). Notably, this type of design-focused task may have its greatest impact on higher-order outcomes, such as creativity, teamwork, and design competence, which are often undermeasured in AR research. More detailed reporting of group processes, including collaboration quality and the content of peer feedback, as well as implementation conditions such as teacher facilitation, time constraints, and technical reliability, would help explain variability across groups and improve reproducibility in classroom settings.

- -

- Case Study: Krüger and Bodemer investigated the application of multimedia design principles in AR learning environments, focusing on the spatial contiguity and coherence principles (Bacca-Acosta et al., 2022). Two studies examined the impact of these principles on cognitive load and knowledge acquisition. In the first study, with 80 participants, researchers examined the spatial integration of virtual and physical elements in AR. Participants experienced an integrated or separated design, with virtual textual information either overlaid on real-world visuals or presented separately on a tablet. Results suggested minor improvements in reducing extraneous cognitive load and enhancing performance with integrated designs, though most effects were not statistically significant. The second study, involving 130 participants, explored the coherence principle by manipulating the addition of matching or non-matching virtual sounds in an AR environment. Contrary to expectations, non-matching sounds did not significantly increase cognitive or task load compared to matching or no sounds (Bacca-Acosta et al., 2022).

5.3. Constructivism, Sociocultural Theory, and Connectivism

- -

- Case Study: Safadel and White explored the use of AR in teaching molecular biology, emphasizing its potential to improve the visualization and comprehension of complex 3D macromolecular structures (Safadel & White, 2019). The study involved 60 university students randomly assigned to either a traditional 2D instructional condition or an AR-enhanced environment. In the AR condition, students used mobile devices to interact with 3D models of molecules, such as DNA, enabling them to rotate, manipulate, and observe structures from multiple perspectives. This AR approach aligned with constructivist and situated learning theories, as it engaged students in active exploration and contextualized learning tasks. Results demonstrated that students in the AR group reported higher satisfaction and usability, and a better understanding of molecular structures, than those in the 2D group (Safadel & White, 2019). This study also points to a key boundary condition for constructivist AR: benefits are more likely when exploration is scaffolded, and learners are prompted to articulate what the visualizations imply, rather than simply manipulating models superficially.

- -

- Case Study: Teo et al. (2022) explored the application of an AR game to improve comprehension of English for Medical Purposes (EMP) among 240 Asian medical undergraduates aged 19–21 (Teo et al., 2022). The AR games integrated multimedia elements into real-life healthcare scenarios, allowing students to practice listening and reading comprehension collaboratively under teacher guidance. AR games created real-life-like scenarios for students to practice comprehension collaboratively, integrating verbal and non-verbal cues to simulate professional contexts. This approach facilitated shared responsibility for learning and enhanced cognitive processes, mainly when students of varying proficiency levels collaborated in heterogeneous groups. The study emphasized that teacher immediacy—close interpersonal communication with students—reduced psychological distance and improved engagement, aligning with the sociocultural focus on mediated learning through interaction (Teo et al., 2022). This case study is particularly informative in showing that teacher-related variables, such as guidance, immediacy, and classroom facilitation, can be decisive implementation conditions for AR-supported collaboration.

- -

- Case Study: Techakosit and Wannapiroon (2015) investigated the design and evaluation of a connectivism learning environment integrated into an AR science laboratory to enhance scientific literacy. The study was conducted in two phases: designing the AR-based learning environment and evaluating its suitability with the input of seven experts in connectivism, AR, and scientific literacy. The AR learning environment was structured around four key components: the learning environment, a process to enhance scientific literacy, environmental characteristics, and measures to foster scientific literacy. The design emphasized connectivist principles, where learners engage in a networked environment to share, research, and reflect on scientific concepts. The AR component enabled students to perform hands-on experiments, collaborate in real time, and visualize complex scientific concepts interactively. Expert evaluations highlighted the environment’s suitability, with ratings indicating a high potential to promote problem-solving skills, collaborative learning, and a deeper understanding of science. The study concluded that integrating AR into science education fosters scientific literacy by bridging theoretical concepts with practical, technology-mediated experiences (Techakosit & Wannapiroon, 2015). Because this case study emphasizes design and expert evaluation, it also underscores the importance of examining implementation and learning effects in authentic classroom settings.

- -

- Case Study: A practical example of an AR application concerning CLT can be seen in a study conducted by Küçük et al., which evaluated an AR application named “MagicBook” (Küçük et al., 2016). Seventy second-year medical students were divided into experimental and control groups. The experimental group used the “MagicBook” to learn neuroanatomy, while the control group used traditional learning methods. The “MagicBook” integrates traditional printed books with AR technology using mobile devices. Students interact with the book by scanning visual markers on the pages using the Aurasma app on their mobile devices. This interaction superimposes multimedia content, such as 3D animations and videos, onto the book pages, allowing students to visualize anatomical structures dynamically and interactively. The results showed that the “MagicBook” students achieved higher academic performance and reported lower cognitive load than the control group. The AR application helped make abstract anatomical concepts more concrete, reducing the mental effort required to understand these concepts. The “MagicBook” enabled information processing through visual and verbal channels, enhancing knowledge transfer to long-term memory (Küçük et al., 2016). This example illustrates how AR can function as an integration tool by aligning visual and verbal information and making spatial relations more concrete, which is consistent with reduced extraneous cognitive load.

6. Educational Topics Addressed by AR and Targeted Age Groups

6.1. Growth in the Number of Studies on AR in Education

6.2. Domains and Target Ages of AR Studies for Education

- -

- Physics: AR can be helpful for physics teaching by offering digital and visual tools that make complex concepts more accessible and concrete (Cai et al., 2013, 2017; Fidan & Tuncel, 2019). For instance, a recent study on 91 students aged 12–14 evaluated the effectiveness of “FenAR”, a marker-based AR software designed to make challenging notions such as force, energy, pressure, and work more accessible. Through tablets, students interacted with realistic three-dimensional models, manipulating virtual objects and observing details from different angles. FenAR also allowed students to explore concepts such as weight and mass in various environments, including on the moon or Mars, thereby facilitating a practical understanding of theoretical ideas. Results showed that students who used AR performed significantly better on learning tests and retained learned concepts longer (Fidan & Tuncel, 2019).

- -

- Natural Sciences: By enabling students to visualize complex phenomena, such as biological cycles, ecosystems, and natural processes, through dynamic three-dimensional models, AR facilitates understanding abstract concepts, stimulates curiosity, and promotes more engaging and accessible learning. For example, a study by Sahin and colleagues involved 100 students aged 12 to 13 from two public middle schools to test their attitudes toward AR applications (Sahin & Yilmaz, 2020). The participants, who had never used AR before, were divided into two groups: an experimental group and a control group. Students in the experimental group studied the module “The Solar System and Beyond” utilizing AR-based teaching materials. These materials consisted of an activity booklet enhanced by educational videos, three-dimensional images of the planets, and key information obtained from the Morpa Campus website. During the lecture, students could interact directly with the 3D representations of the planets and constellations. At the same time, virtual objects were projected onto the whiteboard to create a synchronized, engaging learning environment. Meanwhile, the control group followed the same topic through traditional methods based solely on textbooks and face-to-face lectures. Students in the experimental group performed significantly better on the course evaluation test than their peers in the control group. In addition to academic improvements, the use of AR also positively impacted students’ attitudes toward the subject, making learning more interesting and challenging (Sahin & Yilmaz, 2020).

- -

- Math: Numerous studies have investigated AR solutions for teaching mathematics, particularly for visualizing 3-D graphs or solving geometric problems (J. W. Lai & Cheong, 2022). For example, Kounlaxay et al. studied 40 undergraduate engineering students at Souphanouvong University in Laos to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching three-dimensional geometry in mathematics. Students tried “GeoGebra AR”, an application that allows them to create, visualize, and manipulate three-dimensional geometric objects in a real-world context. During the lessons, students could interact with solid figures such as cubes, cylinders, cones, and prisms, observing how parameters, such as height and radius, affected volume calculations in real time, allowing them to modify the shapes and see the results immediately (Kounlaxay et al., 2021).

- -

- Biology: AR for studying anatomy or processes takes advantage of the unique features of this technology to enable students to visualize complex structures, such as the human body or biological processes, in a three-dimensional and detailed cellular manner (e.g., Afnan & Puspitawati, 2024). An example conducted in this area is the study by Fuchsova, which involved 61 first-year college students in a program for future teachers (Fuchsova & Korenova, 2019). The goal was to improve comprehension of human anatomy using interactive AR applications installed on tablets: “Anatomy 4D” and “The Brain iExplore”. “Anatomy 4D” allowed users to explore the human body in 4D, visualizing body systems in detail to better understand the relationships between organs and physiological processes. On the other hand, “The Brain iExplore” focused on the brain, showing its reactions to sounds and allowing students to delve into functions such as short-term memory through interactive games. During the sessions, students integrated AR applications with traditional textbooks and smartphone research, making learning more flexible. Results showed significant improvement in understanding and memorization of concepts, increased motivation, and development of clinical skills. The immersive and interactive experience provided by AR made learning more engaging (Fuchsova & Korenova, 2019).

- -

- History and Archaeology: With the ability to recreate historical settings, visualize archaeological artifacts in 3D, and integrate contextual information, AR permits exploration of events and places with a level of interactivity and engagement that is difficult to achieve with traditional methods (Barrile et al., 2019; Challenor & Ma, 2019; Gherardini et al., 2020). AR not only facilitates understanding of complex historical events but also promotes historical empathy, helping students connect emotionally with figures and places from the past (C. A. Chen & Lai, 2021). AR applications used at archaeological sites or museums enrich learning, transforming visits into educational experiences that combine technological innovation and cultural insight (Challenor & Ma, 2019). For example, in a study by Chang and colleagues, 87 first-year university students from the Department of Tourism and Leisure in Taiwan participated in a guided tour of historic sites using three modes: an advanced AR app, an audio guide, and no media. The AR allowed them to identify buildings and provide real-time historical information. The results showed a significant improvement in test scores and “Sense of Place” (historical empathy and sense of belonging) in the AR group compared to the others, highlighting that AR is more effective than audio in engaging students and improving learning (Chang et al., 2015).

- -

- Literature: By overlaying digital virtual elements with traditional texts, AR allows students to view animated scenes, explore narrative settings, and interact with story characters, transforming reading into an immersive experience. This approach stimulates students’ imagination and interest and facilitates a deep understanding of texts, developing narrative, critical, and emotional skills in a more dynamic and accessible way than traditional methods. For example, a study by Nezhyva and colleagues explored the use of AR to improve comprehension and interaction with literary works among elementary school children (Nezhyva et al., 2020).

- -

- Foreign Languages: Although the adoption of AR for language learning is still in its early stages, it has shown great potential in assisting learners and educators (Mohd Nabil et al., 2024). According to Larchen Costuchen et al. (2020), AR has proven to be a valuable tool for creating innovative materials and immersive educational technologies for second-language learning, such as AR books (Cheng, 2017), AR flashcards (Tsai, 2018; Yaacob et al., 2019), and AR games (Hu et al., 2022). A significant finding of their study was that incorporating immersive AR experiences into familiar physical environments enhanced vocabulary retrieval performance among twenty-first-century college students learning a second language. Additionally, Y. W. Chen et al. (2019) observed that students exhibited high motivation to learn through contextualized AR-enhanced learning. Skilled learners showed increased motivation in self-efficacy, proactive learning, and perceived learning value.

- -

- Arts: AR is also transforming art education, offering innovative tools to explore artworks, places, and concepts in an interactive, immersive way. Through AR, students and visitors can view hidden details, interact with digital reconstructions, and delve into historical and cultural contexts, making art learning more accessible, engaging, and personalized. For example, in a study on augmented museum experiences, AR enriched Van Gogh’s painting “Starry Night” with visual effects (twinkling stars, reflections on water) and floating descriptive text. Questionnaires showed that verbal elements (descriptions) had a more significant impact on user engagement and willingness to pay for similar experiences, highlighting the importance of relevant informational content- rather than visual effects alone (He et al., 2018). Moreover, a study at the Acropolis Museum in Athens used mobile devices to augment exhibits with AR, creating interactive narrative experiences. Features included videos, games, audio narratives, and digital reconstruction. Although the results have not been published, visitors expressed interest in using AR to get more information about the exhibits (Keil et al., 2013).

7. Discussion

7.1. Enhancing Education Through Augmented Reality: Opportunities and Advancements

7.2. Limits and Barriers to the Use of AR in Education

7.3. Key Points for the Design and Testing of AR Applications for Education

7.4. Implications for Educational Practice and Recommendations for Future Research

7.5. The ARCADE Framework: A Practical Checklist for AR in Education

7.6. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afnan, M. Z., & Puspitawati, R. P. (2024). Exploration of biological concept understanding through augmented reality: A constructivism theory approach. JPBI (Jurnal Pendidikan Biologi Indonesia), 10(3), 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajit, G., Lucas, T., & Kanyan, R. (2021). A systematic review of augmented reality in STEM education. Studies of Applied Economics, 39(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçayır, M., & Akçayır, G. (2017). Advantages and challenges associated with augmented reality for education: A systematic review of the literature. Educational Research Review, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A., & Mohanty, A. (2023). Educational technology: Exploring the convergence of technology and pedagogy through mobility, interactivity, AI, and learning tools. Cogent Engineering, 10(2), 2283282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A. M., Jaboob, M., Garad, A., & Al-Ansi, A. (2023). Analyzing augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) recent development in education. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, W. H. (2022). The affordances of augmented reality technology in the english for specific purposes classroom: It’s impact on vocabulary learning and students motivation in a Saudi higher education institution. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(3), 6588–6602. Available online: https://www.journalppw.com/index.php/jpsp/article/view/3849 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- AlNajdi, S. M. (2022). The effectiveness of using augmented reality (AR) to enhance student performance: Using quick response (QR) codes in student textbooks in the Saudi education system. Educational Technology Research and Development, 70(3), 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A. (2019). Virtual reality, augmented reality and artificial intelligence in special education: A practical guide to supporting students with learning differences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, F., Collotta, M., Pau, G., & Termine, F. (2022). An overview of augmented reality. Computers, 11(2), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariano, R., Manca, M., Paternò, F., & Santoro, C. (2023). Smartphone-based augmented reality for end-user creation of home automations. Behavioral & Information Technology, 43(1), 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydoğdu, F. (2022). Augmented reality for preschool children: An experience with educational contents. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(2), 326–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R. T. (1997). A survey of augmented reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 6(4), 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacca, J., Baldiris, S., Fabregat, R., Graf, S., & Kinshuk. (2014). Augmented reality trends in education: A systematic review of research and applications. Educational Technology & Society, 17(4), 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Bacca-Acosta, J., Duque-Mendez, N. D., Krüger, J. M., & Bodemer, D. (2022). Application and investigation of multimedia design principles in augmented reality learning environments. Information, 13(2), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V., Fotia, A., Bilotta, G., & De Carlo, D. (2019). Integration of geomatics methodologies and creation of a cultural heritage app using augmented reality. Virtual Archaeology Review, 10(20), 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., & Damasio, A. R. (2005). The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games and Economic Behavior, 52, 336–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, C., Baixauli, I., Gómez, S., Andrés, M. de E. P., & De Stasio, S. (2020). Exploring the impact of augmented reality in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K. R., Verma, V., & Craig, S. D. (2025). Mobile augmented reality impacts engagement, but not learning. Computers & Education: X Reality, 7, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhushan, S., Arunkumar, S., Eisa, T. A. E., Nasser, M., Singh, A. K., & Kumar, P. (2024). AI-enhanced dyscalculia screening: A survey of methods and applications for children. Diagnostics, 14(13), 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinghurst, M., & Dünser, A. (2012). Augmented reality in the classroom. Computer, 45(7), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, O., & Raskar, R. (2005). Spatial augmented reality merging real and virtual worlds. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biocca, F. (1997). The cyborg’s dilemma: Progressive embodiment in virtual environments. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3(2), JCMC324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, M., Howe, C., McCredie, N., Robinson, A., & Grover, D. (2014). Augmented reality in education—Cases, places and potentials. Educational Media International, 51(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1997). The culture of education. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchau, A., Rucker, W. M., Wössner, U., & Becker, M. (2009). Augmented reality in teaching of electrodynamics. COMPEL—The International Journal for Computation and Mathematics in Electrical and Electronic Engineering, 28(4), 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, J., Buntins, K., & Kerres, M. (2022). The impact of augmented reality on cognitive load and performance: A systematic review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., Chiang, F. K., Sun, Y., Lin, C., & Lee, J. J. (2017). Applications of augmented reality-based natural interactive learning in magnetic field instruction. Interactive Learning Environments, 25(6), 778–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S., Chiang, F.-K., & Wang, X. (2013). Using the augmented reality 3D technique for a convex imaging experiment in a physics course. International Journal of Engineering Education, 29, 856–865. [Google Scholar]

- Cakir, R., & Korkmaz, O. (2019). The effectiveness of augmented reality environments on individuals with special education needs. Education and Information Technologies, 24(2), 1631–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, P., Pessanha, S., & Jorge, J. (2011). Fostering collaboration in kindergarten through an augmented reality game. International Journal of Virtual Reality, 10(3), 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecchi, I., Borghini, T., Bellotti, M., & Bernetti, I. (2025). Enhancing education outcomes integrating augmented reality and artificial intelligence for education in nutrition and food sustainability. Sustainability, 17(5), 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, J., & Furht, B. (2011). Augmented reality: An overview. In Handbook of augmented reality (pp. 3–46). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales, A., Laguna, I., Pérez-López, D., Perona, P., & Contero, M. (2013). An experience on natural sciences augmented reality contents for preschoolers. In Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics), 8022 LNCS (PART 2) (pp. 103–112). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudell, T. P., & Mizell, D. W. (2003, January 7–10). Augmented reality: An application of heads-up display technology to manual manufacturing processes. Twenty-Fifth Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (Vol. 2, pp. 659–669), Kauai, HI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenor, J., & Ma, M. (2019). A review of augmented reality applications for history education and heritage visualisation. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 3(2), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-L., Hou, H.-T., Pan, C.-Y., Sung, Y.-T., & Chang, K.-E. (2015). Apply an augmented reality in a mobile guidance to increase sense of place for heritage places. Educational Technology & Society, 18(2), 1176–3647. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. A., & Lai, H. I. (2021). Application of augmented reality in museums—Factors influencing the learning motivation and effectiveness. Science Progress, 104(3), 003685042110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. W., Liu, G. Z., Lin, V., & Wang, H. Y. (2019). Needs analysis for an ESP case study developed for the context-aware ubiquitous learning environment. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 34(1), 124–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. H. (2017). Reading an augmented reality book: An exploration of learners’ cognitive load, motivation, and attitudes. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33(4), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K. H., & Tsai, C. C. (2013). Affordances of augmented reality in science learning: Suggestions for future research. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 22(4), 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A., Mystakidis, S., Bellavista, P., Kapetanaki, A., Krouska, A., Troussas, C., & Sgouropoulou, C. (2022). Exploiting augmented reality technology in special education: A systematic review. Computers, 11(10), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. (2008). Supersizing the mind: Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Pfeiffer & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Czok, V., Krug, M., Müller, S., Huwer, J., & Weitzel, H. (2023). Learning effects of augmented reality and game-based learning for science teaching in higher education in the context of education for sustainable development. Sustainability, 15(21), 15313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ error: Emotion, reason, and the human brain. Penguin Group. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P., Zhu, M., McLaughlin, L., Bilgrami, Z., & Milanaik, R. L. (2017). Augmented reality video games: New possibilities and implications for children and adolescents. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 1(2), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M., Roberto, R. A., Teichrieb, V., & Cavalcante, P. S. (2016, March 19). Towards the development of guidelines for educational evaluation of augmented reality tools. 2016 IEEE Virtual Reality Workshop on K-12 Embodied Learning through Virtual and Augmented Reality, KELVAR 2016 (pp. 17–21), Greenville, SC, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, D. F. O., Menezes, B. H. X. M., & Araújo, C. C. (2014). Building a quality mobile application: A user-centered study focusing on design thinking, user experience and usability. In Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics), 8518 LNCS (PART 2) (pp. 313–322). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dourish, P. (2001). Where the action is: The foundations of embodied interaction. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, S. (2007). What connectivism is. Available online: https://www.downes.ca/post/38653 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Dunleavy, M., Dede, C., & Mitchell, R. (2009). Affordances and limitations of immersive participatory augmented reality simulations for teaching and learning. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 18(1), 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlach, N. I., & Mavor, A. S. (1995). Virtual reality: Scientific and technological challenges. National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, M., Volmerg, J. S., & Friedrich, C. M. (2019). Augmented reality in medicine: Systematic and bibliographic review. JMIR MHealth and UHealth, 7(4), e10967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elford, D., Lancaster, S. J., & Jones, G. A. (2022). Exploring the effect of augmented reality on cognitive load, attitude, spatial ability, and stereochemical perception. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 31(3), 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M., Antle, A. N., & Warren, J. L. (2020). Augmented reality for early language learning: A systematic review of augmented reality application design, instructional strategies, and evaluation outcomes. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 58(6), 1059–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W., Chen, L., Zhang, T., Chen, C., Teng, Z., & Wang, L. (2023). Head-mounted display augmented reality in manufacturing: A systematic review. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 83, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farao, J., Malila, B., Conrad, N., Mutsvangwa, T., Rangaka, M. X., & Douglas, T. S. (2020). A user-centred design framework for mHealth. PLoS ONE, 15(8), e0237910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feiner, S., MacIntyre, B., Höllerer, T., & Webster, A. (1997). A touring machine: Prototyping 3D mobile augmented reality systems for exploring the urban environment. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 1(4), 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, M., & Tuncel, M. (2019). Integrating augmented reality into problem based learning: The effects on learning achievement and attitude in physics education. Computers and Education, 142, 103635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, X., & Coutellier, D. (2007). Research in interactive design. In Research in interactive design. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J. A. (1983). Modularity of mind: ICTs, development, and the capabilities approach. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchsova, M., & Korenova, L. (2019). Visualisation in basic science and engineering education of future primary school teachers in human biology education using augmented reality. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 8(1), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, M., Kosch, T., & Schmidt, A. (2016). Interactive worker assistance: Comparing the effects of in-situ projection, head-mounted displays, tablet, and paper instructions. In UbiComp 2016—Proceedings of the 2016 ACM international joint conference on pervasive and ubiquitous computing (pp. 934–939). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J., Kinshuk, Baldiris, S., Gutiérrez, J., & Pavón, J. (2020). How do pedagogical approaches affect the impact of augmented reality on education? A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Educational Research Review, 31, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J., Pellas, N., Söbke, H., Wen, Y., & Ricart, C. P. (2021). An overview of twenty-five years of augmented reality in education. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 5(7), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardini, F., Santachiara, M., & Leali, F. (2020). Enhancing heritage fruition through 3D virtual models and augmented reality: An application to Roman artefacts. Virtual Archaeology Review, 10(21), 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, C. H., Jr. (2020). Augmented reality for education: A review. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 5(6), 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2016). Augmented reality and language learning: From annotated vocabulary to place-based mobile games. Emerging Technologies, 20(3), 9–19. Available online: http://llt.msu.edu/issues/october2016/emerging.pdfhttp://llt.msu.edu/issues/october2016/emerging.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, A. T., & Wang, M. (2018). Augmented reality and mobile learning: Theoretical foundations and implementation. In Mobile learning and higher education (pp. 41–55). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, E. T., & Atasoy, B. (2017). The effects of augmented reality on elementary school students’ spatial ability and academic achievement. Egitim ve Bilim-Education and Science, 42(191), 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneefa, F. M., Shoufan, A., & Damiani, E. (2024). The essentials: A comprehensive survey to get started in augmented reality. IEEE Access, 12, 109012–109070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H. U., Saragih, E., Mahriyuni, & Gapur, A. (2024). Enhancing augmented reality (AR) technology to improve medical english literacy. International Journal Linguistics of Sumatra and Malay, 2(2), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkilä, J., Väyrynen, J., Suoheimo, M., & Colley, A. (2018). Exploring head mounted display based augmented reality for factory workers. In ACM international conference proceeding series (pp. 499–505). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Wu, L., & Li, X. (2018). When art meets tech: The role of augmented reality in enhancing museum experiences and purchase intentions. Tourism Management, 68, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. (1927). Sein und zeit. Max Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Heilig, M. (1962). Sensorama (U.S. Patent , No. 3050870A). U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. [Google Scholar]

- Hellermann, J., Thorne, S. L., & Fodor, P. (2017). Mobile reading as social and embodied practice. Classroom Discourse, 8(2), 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, H., Sukmawarti, S., & Suwanto, S. (2021). The application of augmented reality in elementary school education. Research, Society and Development, 10(3), e14910312823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y. S., Lin, Y. H., & Yang, B. (2017). Impact of augmented reality lessons on students’ STEM interest. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 12(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., Yuan, Y., Chen, Q., Kang, X., & Zhu, Y. (2022). The practice and application of AR games to assist children’s english pronunciation teaching. Occupational Therapy International, 2022, 3966740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-C., Chen, M.-Y., & Hsu, W.-P. (2019). Do learning styles matter? Motivating learners in an augmented geopark. Educational Technology & Society, 22(1), 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, M. B., & Delgado-Kloos, C. (2018). Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M. B., Di Serio, Á., Villarán, D., & Delgado Kloos, C. (2014). Experimenting with electromagnetism using augmented reality: Impact on flow student experience and educational effectiveness. Computers & Education, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D. H. (1991). Objectivism versus constructivism: Do we need a new philosophical paradigm? Educational Technology Research and Development, 39(3), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, A. (1990). User Interface: A Personal View. In The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design (pp. 191–207). Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlaris, G. C., Keramopoulos, E., Bratsas, C., & Kokkonis, G. (2025). Augmented reality in education through collaborative learning: A systematic literature review. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 9(9), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, J., Pujol, L., Roussou, M., Engelke, T., Schmitt, M., Bockholt, U., & Eleftheratou, S. (2013, October 28–November 1). A digital look at physical museum exhibits: Designing personalized stories with handheld augmented reality in museums. DigitalHeritage 2013—Federating the 19th Int’l VSMM, 10th Eurographics GCH, and 2nd UNESCO Memory of the World Conferences (pp. 685–688), Marseille, France. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khowaja, K., Banire, B., Al-Thani, D., Sqalli, M. T., Aqle, A., Shah, A., & Salim, S. S. (2020). Augmented reality for learning of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A systematic review. IEEE Access, 8, 78779–78807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., Mainemelis, C., Sternberg, R. J., & Zhang, L. F. (2000). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kounlaxay, K., Shim, Y., Kang, S. J., Kwak, H. Y., & Kim, S. K. (2021). Learning media on mathematical education based on augmented reality. KSII Transactions on Internet and Information Systems, 15(3), 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutromanos, G., Sofos, A., & Avraamidou, L. (2015). The use of augmented reality games in education: A review of the literature. Educational Media International, 52(4), 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, H., & Güner-Yildiz, N. (2021). Augmented reality (AR) as a learning material in special needs education. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1921–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, M., Thoms, L.-J., & Huwer, J. (2023). Augmented reality in the science classroom—Implementing pre-service teacher training in the competency area of simulation and modeling according to the DiKoLAN framework. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumparak, G. (2017). Pokémon GO gets a new and improved augmented reality mode (but only on iOS). TechCrunch. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2017/12/20/pokemon-go-gets-a-new-and-improved-augmented-reality-mode-but-only-on-ios/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Küçük, S., Kapakin, S., & Göktaş, Y. (2016). Learning anatomy via mobile augmented reality: Effects on achievement and cognitive load. Anatomical Sciences Education, 9(5), 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J. W., & Cheong, K. H. (2022). Adoption of virtual and augmented reality for mathematics education: A scoping review. IEEE Access, 10, 13693–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J. W. M., & Bower, M. (2019). How is the use of technology in education evaluated? A systematic review. Computers & Education, 133, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larchen Costuchen, A., Darling, S., & Uytman, C. (2020). Augmented reality and visuospatial bootstrapping for second-language vocabulary recall. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 15(4), 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liono, R. A., Amanda, N., Pratiwi, A., & Gunawan, A. A. S. (2021). A systematic literature review: Learning with visual by the help of augmented reality helps students learn better. Procedia Computer Science, 179, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, J. H., Lai, Y. F., & Hsu, T. L. (2021). The study of ar-based learning for natural science inquiry activities in taiwan’s elementary school from the perspective of sustainable development. Sustainability, 13(11), 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A., Valentim, N., Moraes, B., Zilse, R., & Conte, T. (2018). Applying user-centered techniques to analyze and design a mobile application. Journal of Software Engineering Research and Development, 6(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Belmonte, J., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., López-Núñez, J. A., & Hinojo-Lucena, F. J. (2023). Augmented reality in education. A scientific mapping in Web of Science. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(4), 1860–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S. N. A., & Salam, A. R. (2021). A systematic review of augmented reality applications in language learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 16(10), 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisha, & Gargrish, S. (2023). Augmented Reality and education: A comprehensive review and analysis of methodological considerations in empirical studies. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 19(3), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed., pp. 1–304). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2012). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (pp. 31–48). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDiarmid, G. W., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Time to rethink: Educating for a technology-transformed world. ECNU Review of Education, 6(2), 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, B., & Yang, S. (2019). Nurturing environmental education at the tertiary education level in China: Can mobile augmented reality and gamification help? Sustainability, 11(16), 4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing. Available online: http://www.myilibrary.com?id=915387 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Milgram, P., Takemura, H., Utsumi, A., & Kishino, F. (1994). Augmented reality: A class of displays on the reality–virtuality continuum. In Proceedings of SPIE, vol. 2351, telemanipulator and telepresence technologies. SPIE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Nabil, N. S., Nordin, H., & Ab Rahman, F. (2024). Immersive language learning: Evaluating augmented reality filter for ESL speaking fluency teaching. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching and Learning, 17(2), 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R. (2004). Decreasing cognitive load for novice students: Effects of explanatory versus corrective feedback in discovery-based multimedia. Instructional Science, 32(1–2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, F., & Riva, G. (2006). Conoscenza, comunicazione e tecnologia. Aspetti cognitivi della realtà virtuale. LED Edizioni Universitarie. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhyva, L., Palamar, S., Vaskivska, H., Kotenko, O., Nazarenko, L., Naumenko, M., & Voznyak, A. (2020). Augmented reality in the literary education of primary school children: Specifics, creation, application. In Proceedings of the 1st symposium on advances in educational technology (pp. 283–291). SciTePress. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. T., & Dang, T. (2017). Setting up virtual reality and augmented reality learning environment in unity. In Adjunct proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international symposium on mixed and augmented reality, ISMAR-adjunct 2017 (pp. 315–320). IEEE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S. A., Perifanou, M., & Economides, A. A. (2024). Educators’ ability to use augmented reality (AR) for teaching based on the TARC framework: Evidence from an international study. In Lecture notes in networks and systems, 936 LNNS (pp. 69–77). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oranç, C., & Küntay, A. C. (2019). Learning from the real and the virtual worlds: Educational use of augmented reality in early childhood. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 21, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F. (2020). Psicologia della realtà virtuale: Aspetti tecnologici, teorie e applicazioni per il benessere mentale. Mondadori Università. [Google Scholar]

- Parmaxi, A., Athanasiou, A., & Α Demetriou, A. (2021). Introducing a student-led application of Google expeditions: An exploratory study. Educational Media International, 58(1), 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmaxi, A., & Demetriou, A. A. (2020). Augmented reality in language learning: A state-of-the-art review of 2014–2019. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 36(6), 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1973). To understand is to invent: The future of education. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, J., Cerón, J., & Baldiris, S. (2025). CooperAR: Supporting the design and implementation of augmented inclusive educational scenarios. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1571104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, I. (2014). Augmented reality in education: A meta-review and cross-media analysis. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 18(6), 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N. A., Mailok, R., & Husain, M. (2020). Mobile augmented reality learning application for students with learning disabilities. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(2), 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridha, A. M., & Shehieb, W. (2021, September 12–17). Assistive technology for hearing-impaired and deaf students utilizing augmented reality. 2021 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE) (pp. 1–5), Virtual. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safadel, P., & White, D. (2019). Facilitating molecular biology teaching by using augmented reality (AR) and protein data bank (PDB). TechTrends, 63(2), 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, D., & Yilmaz, R. M. (2020). The effect of Augmented Reality Technology on middle school students’ achievements and attitudes towards science education. Computers & Education, 144, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. E. C., Lübke, A. in W., Taketomi, T., Yamamoto, G., Rodrigo, M. M. T., Sandor, C., & Kato, H. (2016). Augmented reality as multimedia: The case for situated vocabulary learning. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 11(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavarelli, A., Arya, A., & Teather, R. J. (2021). Virtual reality and augmented reality in social learning spaces: A literature review. Virtual Reality, 25(1), 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, T. S., & Mohamed, A. M. (2024). Exploring the effectiveness of augmented reality technology on reading comprehension skills among early childhood pupils with learning disabilities. Journal of Computers in Education, 11(2), 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L. A. (2010). Embodied cognition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shapovalov, V. B., Shapovalov, Y. B., Bilyk, Z. I., Megalinska, A. P., & Muzyka, I. O. (2019). The Google Lens analyzing quality: An analysis of the possibility to use in the educational process. International Workshop on Augmented Reality in Education, 2547, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(2). Available online: http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Sirakaya, M., & Cakmak, E. K. (2018). The effect of augmented reality use on achievement, misconception and course engagement. Contemporary Educational Technology, 9(3), 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sırakaya, M., & Alsancak Sırakaya, D. (2022). Augmented reality in STEM education: A systematic review. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(8), 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, I. E. (1964). Sketch pad a man-machine graphical communication system. In Proceedings of the SHARE design automation workshop on—DAC ’64 (pp. 6.329–6.346). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünger, I., & Çankaya, S. (2019). Augmented reality: Historical development and area of usage. Journal of Educational Technology and Online Learning, 2(3), 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydorenko, T., Hellermann, J., Thorne, S. L., & Howe, V. (2019). Mobile augmented reality and language-related episodes. TESOL Quarterly, 53(3), 712–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H. A., Sullivan, D., Mullen, C., & Johnson, C. M. (2011). Implementation of a user-centered framework in the development of a web-based health information database and call center. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 44(5), 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techakosit, S., & Wannapiroon, P. (2015). Connectivism learning environment in augmented reality science laboratory to enhance scientific literacy. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 2108–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C. H., Chen, J. Y., & Chen, Z. H. (2017). Impact of augmented reality on programming language learning: Efficiency and perception. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 56(2), 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T., Khazaie, S., & Derakhshan, A. (2022). Exploring teacher immediacy-(non)dependency in the tutored augmented reality game-assisted flipped classrooms of English for medical purposes comprehension among the Asian students. Computers & Education, 179, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevin, L., & Brock, A. M. (2018). Augmented reality for people with visual impairments: Designing and creating audio-tactile content from existing objects. In Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics), 10897 LNCS (pp. 193–200). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., & Ironsi, C. S. (2025). Examining the impact of augmented reality on students’ learning outcomes. Science Reports, 15, 36957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C. C. (2018). A comparison of EFL elementary school learners’ vocabulary efficiency by using flashcards and augmented reality in Taiwan Cheng-Chang Tsai Taiwan. The New Educational Review, 51, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandekerckhove, P., De Mul, M., Bramer, W. M., & De Bont, A. A. (2020). Generative participatory design methodology to develop electronic health interventions: Systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e13780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisberg, E., Ong, J., Masalkhi, M., Zaman, N., Sarker, P., Lee, A. G., & Tavakkoli, A. (2024a). Apple vision pro and the advancement of medical education with extended reality. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 15(1), 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisberg, E., Ong, J., Masalkhi, M., Zaman, N., Sarker, P., Lee, A. G., & Tavakkoli, A. (2024b). Apple vision pro and why extended reality will revolutionize the future of medicine. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 193(1), 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y., Liu, G. Z., & Hwang, G. J. (2017). Integrating socio-cultural contexts and location-based systems for ubiquitous language learning in museums: A state of the art review of 2009–2014. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Callaghan, V., Bernhardt, J., White, K., & Peña-Rios, A. (2018). Augmented reality in education and training: Pedagogical approaches and illustrative case studies. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, 9(5), 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. T., Lin, Y. L., & Lu, H. E. (2022). Exploring the effect of improved learning performance: A mobile augmented reality learning system. Education and Information Technologies, 28(6), 7509–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodson, W., Tillman, P., & Tillman, B. (1992). Human factors design handbook. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C., & Huang, C.-H. (2020, May 31). Situated learning in a course of augmented reality technology. International E-Conference on Advances in Engineering, Technology and Management—ICETM 2020 (pp. 47–52), Virtual. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. K., Lee, S. W. Y., Chang, H. Y., & Liang, J. C. (2013). Current status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education. Computers & Education, 62, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacob, A., Zaludin, F., Aziz, N., Ahmad, N., Othman, N. A., Adawiyah, R., & Fakhruddin, M. (2019). Augmented reality (Ar) flashcards as a tool to improve rural low ability students’ vocabulary. Practitioner Research, 1, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamiri, M., & Esmaeili, A. (2024). Methods and technologies for supporting knowledge sharing within learning communities: A systematic literature review. Administrative Sciences, 14(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., Wang, M., & Wu, J. G. (2020). Design and implementation of augmented reality for english language education. In Springer series on cultural computing (pp. 217–234). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulhaida Masmuzidin, M., & Azah Abdul Aziz, N. (2018). The current trends of augmented reality in early childhood education. The International Journal of Multimedia & Its Applications (IJMA), 10(6), 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AR (Augmented Reality) | VR (Virtual Reality) | MR (Mixed Reality) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual environment | Overlay of digital content in a real environment | Totally virtual, computer-created environment | Integration of virtual and real objects in real time |

| Interaction with the Real Environment | The real environment remains visible and interacts with digital objects | There is no interaction with the real environment. Everything is virtual | Virtual and real objects interact in real time. |

| Technology Used | Smartphones, tablets, AR HMDs (open) | VR HMDs (close), audio headsets, and motion sensors for an immersive experience | Advanced MR HMDs (open) and tracking systems. |

| AR Feature | Learning Theory | Learning Mechanism | Design Implications | Typical Outcome to Assess |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial tracking and anchoring (stable 3D objects in space) | Embodied Cognition Embodied Interaction | Supports perception– action coupling and “embodied” manipulation | Ensure stable tracking (e.g., low latency) and keep gestures natural and simple | Learning gain, engagement, presence |

| In situ overlay (information superimposed on real context) | Situated Learning | Ties knowledge to the physical situation and supports contextualized understanding | Use authentic tasks, keep overlays minimal and context-relevant | Transfer, retention, motivation |

| Interactive manipulation (rotate, assembly) | Experiential Learning Connectivism | Active meaning-making and problem-solving through exploration | Use problem-based tasks, scaffolding, and short debrief/reflection | Problem-solving performance, quality of explanations |

| Multimedia contiguity (labels/text placed on/near the object) | Contiguity Principle of Multimedia Learning | Reduces split-attention and integrates visual–verbal information | Place labels on the object, avoid redundancy and decorative overload | Recall/comprehension, perceived cognitive load |

| Segmentation (step-by-step guidance, progressive disclosure) | Cognitive Load Theory | Manages complexity and reduces extraneous processing | Chunk content, adapt guidance to prior knowledge, and avoid long uninterrupted. sequences | Error rate, time-on-task, cognitive load |

| Real-time feedback and contextual hints | Constructivism | Supports self-regulation and timely correction during activity | Make feedback brief, specific, and non-intrusive | Self-efficacy, performance accuracy |

| Multi-user collaborative AR (shared AR scenarios) | Sociocultural Theory | Co-construction and negotiation of meaning with peers | Define roles and interdependence, provide coordination supports | Collaboration quality, learning outcomes |

| ARCADE Step | Core Question | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|

| A—Align | What are the learning goals, learners, and constraints? | Specify learning objectives, learner characteristics, setting, duration, resources, and constraints (e.g., devices, time). |

| R—Rationale | Why should AR help here (mechanism/theory)? | Link AR use to a theory-driven mechanism (e.g., embodied cognition, situated learning,). State how AR affordances are expected to activate that mechanism. |

| C—Configure | Which AR design choices best support the mechanism (without overload)? | Select AR type (i.e., mobile, wearable, spatial) and core affordances (e.g., anchoring, feedback, collaboration). Minimize extraneous load (e.g., limit overlay density). |

| A—Activate | Can the intervention run reliably and equitably in the real setting? | Plan training, classroom orchestration, teacher facilitation, time-on-task, and contingencies for technical failures. Address accessibility (e.g., device availability, inclusive design). |

| D—Document | What happened in a way others can interpret and reuse? | Report learning outcomes together with mechanism-aligned process indicators (e.g., cognitive load, interaction quality) and qualitative feedback. |

| E—Evolve | How should the intervention be refined and adapted based on evidence and context? | Use results and implementation feedback to iteratively refine the AR experience and its educational supports. Specify what is core vs. adaptable, clarify boundary conditions and resource requirements to support cross-study comparability and replication. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pallavicini, F.; Anesa, P. A Narrative Review on Augmented Reality in Education. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020261

Pallavicini F, Anesa P. A Narrative Review on Augmented Reality in Education. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020261

Chicago/Turabian StylePallavicini, Federica, and Patrizia Anesa. 2026. "A Narrative Review on Augmented Reality in Education" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020261

APA StylePallavicini, F., & Anesa, P. (2026). A Narrative Review on Augmented Reality in Education. Education Sciences, 16(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020261