Bot or Not? Differences in Cognitive Load Between Human- and Chatbot-Led Post-Simulation Debriefings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Debriefing

2.2. Cognitive Load

2.3. Debriefing and Cognitive Load

Chatbots as Debriefers

2.4. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- Perceived intrinsic cognitive load will be higher after a chatbot-led debriefing compared to a moderator-led debriefing.

- Perceived extraneous cognitive load will be higher after a chatbot-led debriefing compared to a moderator-led debriefing.

- Perceived germane cognitive load will be lower after a chatbot-led debriefing compared to a moderator-led debriefing.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Measurement Instruments

4. Results

4.1. Prerequisites

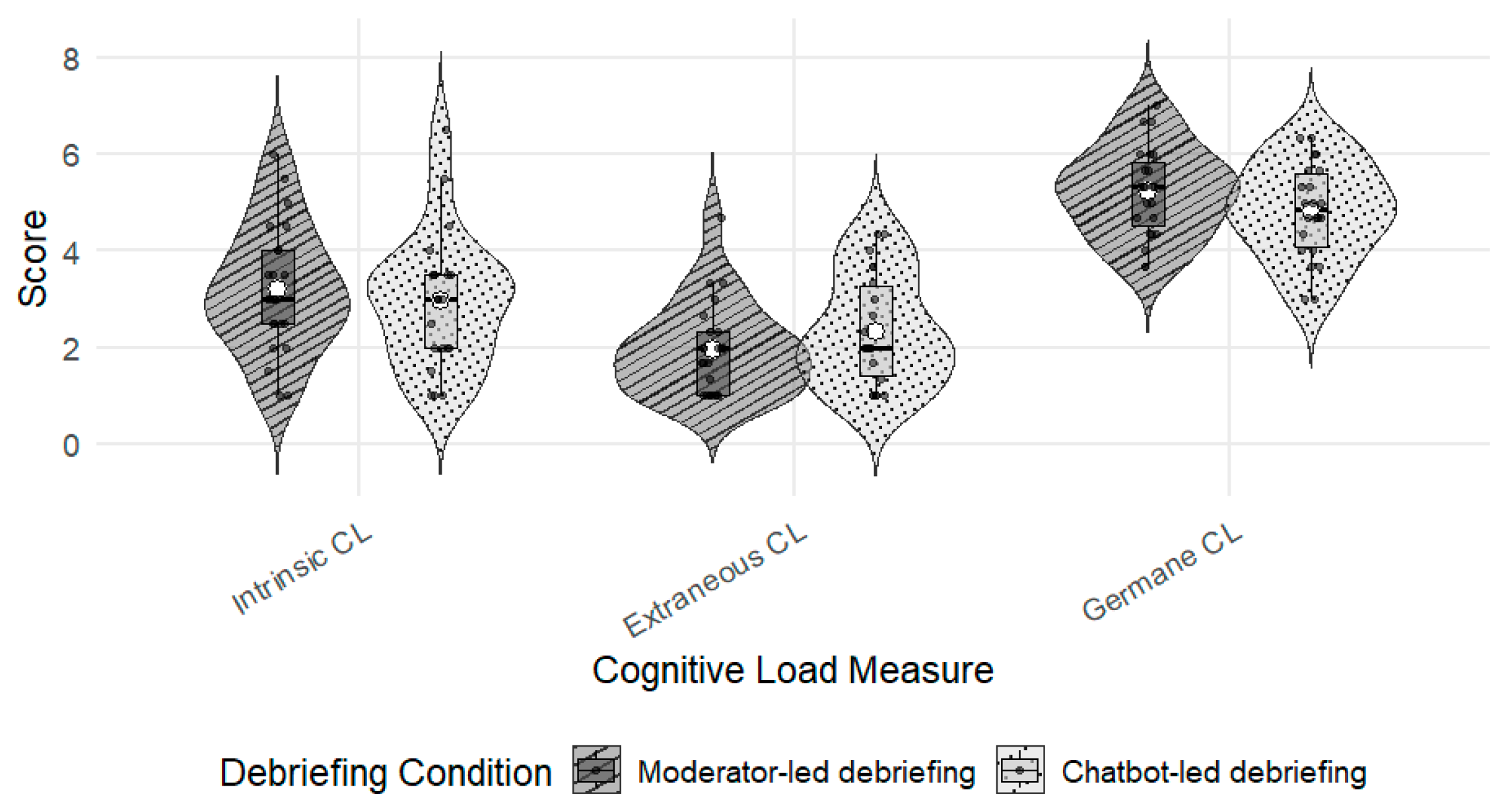

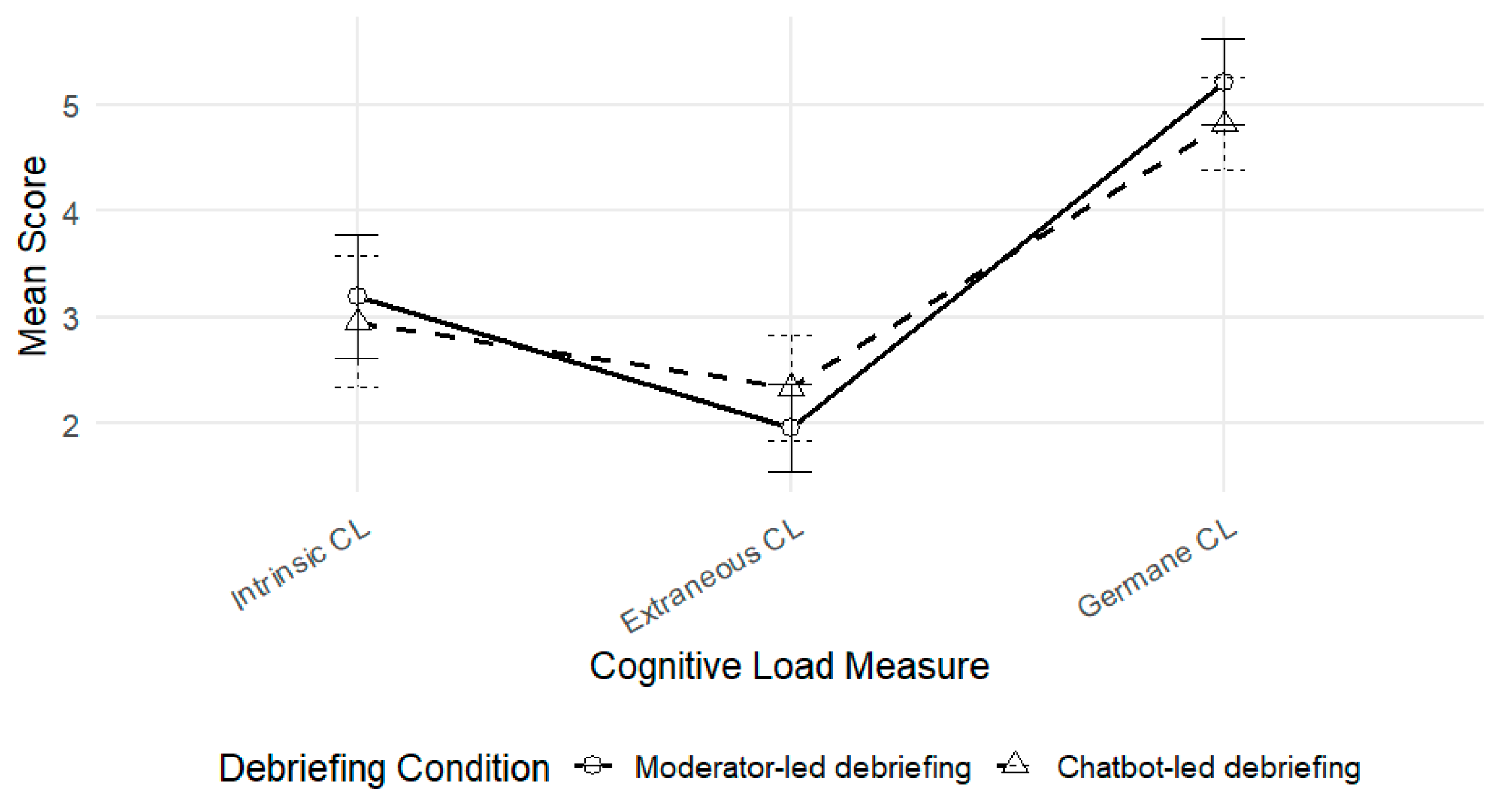

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| INACSL | International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| CLT | Cognitive Load Theory |

| ICL | Intrinsic Cognitive Load |

| ECL | Extraneous Cognitive Load |

| GCL | Germane Cognitive Load |

References

- Boet, S., Bould, M. D., Bruppacher, H. R., Desjardins, F., Chandra, D. B., & Naik, V. N. (2011). Looking in the mirror: Self-debriefing versus instructor debriefing for simulated crises*. Critical Care Medicine, 39(6), 1377–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boet, S., Bould, M. D., Fung, L., Qosa, H., Perrier, L., Tavares, W., Reeves, S., & Tricco, A. C. (2014). Transfer of learning and patient outcome in simulated crisis resource management: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 61(6), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braund, H., Hall, A. K., Caners, K., Walker, M., Dagnone, D., Sherbino, J., Sibbald, M., Wang, B., Howes, D., Day, A. G., Wu, W., & Szulewski, A. (2025). Evaluating the value of eye-tracking augmented debriefing in medical simulation—A pilot randomized controlled trial. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 20(3), 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, M. A. (2008). The importance of debriefing in clinical simulations. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 4(2), e19–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, P., & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive load theory and the format of instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8(4), 293–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A., Grant, V., Huffman, J., Burgess, G., Szyld, D., Robinson, T., & Eppich, W. (2017). Coaching the debriefer: Peer coaching to improve debriefing quality in simulation programs. Simulation in Healthcare, 12(5), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A., Kolbe, M., Grant, V., Eller, S., Hales, R., Symon, B., Griswold, S., & Eppich, W. (2020). A practical guide to virtual debriefings: Communities of inquiry perspective. Advances in Simulation, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronister, C., & Brown, D. (2012). Comparison of simulation debriefing methods. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 8(7), e281–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crookall, D. (2023). Debriefing: A practical guide. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dreifuerst, K. T. (2015). Getting started with debriefing for meaningful learning. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 11(5), 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrene, C., & Young, A. (2014). Successful debriefing—Best methods to achieve positive learning outcomes: A literature review. Nurse Education Today, 34(3), 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppich, W., & Cheng, A. (2015). Promoting Excellence and Reflective Learning in Simulation (PEARLS): Development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simulation in Healthcare, 10(2), 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, D., Klar, M., Träg, K., Mulders, M., Marnitz, M., & Rahner, L. (2025, September 8–11). GenAI-chatbots as debriefers: Investigating the role conformity and learner interaction in counseling training. 23. Fachtagung Bildungstechnologien (DELFI 2025) (pp. 41–55), Freiberg, Germany. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, D., Mulders, M., & Träg, K. H. (2026). Debriefing in virtual reality simulations for the development of counseling competences: Human-led or AI-guided? Tech Know Learn. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favolise, M. (2024). Post-simulation debriefing methods: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 105(4), e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fey, M. K., & Jenkins, L. S. (2015). Debriefing practices in nursing education programs: Results from a national study. Nursing Education Perspectives, 36(6), 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, K., & McLaughlin, K. (2019). Temporal pattern of emotions and cognitive load during simulation training and debriefing. Medical Teacher, 41(2), 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, A. L., Le Fevre, D. M., Waddington, H. L., & Weller, J. M. (2015). Debriefing after simulation-based non-technical skill training in healthcare: A systematic review of effective practice. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 43(3), 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J. S., Moss, J., Epps, C., & Watts, P. (2010). Using video-facilitated feedback to improve student performance following high-fidelity simulation. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 6(5), e177–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, S. K., Jeffe, D. B., Manga, A., Murray, D. J., & Emke, A. R. (2023). Cognitive load assessment scales in simulation: Validity evidence for a novel measure of cognitive load types. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 18(3), 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hense, J., & Kriz, W. C. (2008). Making simulation games an even more powerful tool. Introducing the theory-based evaluation approach. In L. de Caluwé, G. J. Hofstede, & V. Peters (Eds.), Why do games work (pp. 211–217). Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, W., Bialik, M., & Fadel, C. (2019). Artificial intelligence in education promises and implications for teaching and learning. Center for Curriculum Redesign. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10139722/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ifenthaler, D., Majumdar, R., Gorissen, P., Judge, M., Mishra, S., Raffaghelli, J., & Shimada, A. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: Implications for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 29(4), 1693–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INACSL Standards Committee. (2016). INACSL standards of best practice: SimulationSM debriefing. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 12, S21–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory: How many types of load does it really need? Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E., Seßler, K., Küchemann, S., Bannert, M., Dementieva, D., Fischer, F., Gasser, U., Groh, G., Günnemann, S., & Hüllermeier, E. (2023). ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and Individual Differences, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlyl, A., Hall, P., & Bull, S. (2007). Bringing chatbots into education: Towards natural language negotiation of open learner Models. In R. Ellis, T. Allen, & A. Tuson (Eds.), Applications and innovations in intelligent systems XIV (pp. 179–192). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, M. (2025). Generative AI Chatbots for self-regulated learning while balancing cognitive load: Perceptions, interaction patterns, and instructional designs in K-12 learning [Doctoral dissertation, Universität Duisburg-Essen]. [Google Scholar]

- Klepsch, M., Schmitz, F., & Seufert, T. (2017). Development and validation of two instruments measuring intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=de&lr=&id=jpbeBQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=Kolb,+D.+A.+(1984).+Experiential+learning:+Experience+as+the+source+of+learning+and+development.+Englewood+Cliffs,+NJ:+Prentice+Hall.+&ots=Vp6UnY0XRc&sig=yjWgem4qHWdpPjcPPvGRGi_EnXI (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Koole, S., Dornan, T., Aper, L., De Wever, B., Scherpbier, A., Valcke, M., Cohen-Schotanus, J., & Derese, A. (2012). Using video-cases to assess student reflection: Development and validation of an instrument. BMC Medical Education, 12(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriz, W. C., & Nöbauer, B. (2015). Den lernerfolg mit debriefing von Planspielen sichern. Bertelsmann. [Google Scholar]

- Kriz, W. C., Saam, N., Pichlbauer, M., & Fröhlich, W. (2007). Intervention mit planspielenals Großgruppenmethode–Ergebnisse einer interviewstudie. In Planspiele für die organisationsentwicklung. schriftenreihe: Wandel und kontinuität in organisationen (Vol. 8, pp. 103–122). Wissenschaftlicher Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P., Harrison, N. M., McAleer, K., Khan, I., & Somerville, S. G. (2025). Exploring the role of self-led debriefings within simulation-based education: Time to challenge the status quo? Advances in Simulation, 10(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppink, J., Paas, F., Van der Vleuten, C. P., Van Gog, T., & Van Merriënboer, J. J. (2013). Development of an instrument for measuring different types of cognitive load. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1058–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.-C., & Hwang, G.-J. (2023). A robot-based digital storytelling approach to enhancing EFL learners’ multimodal storytelling ability and narrative engagement. Computers & Education, 201, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luctkar-Flude, M., Tyerman, J., Verkuyl, M., Goldsworthy, S., Harder, N., Wilson-Keates, B., Kruizinga, J., & Gumapac, N. (2021). Effectiveness of debriefing methods for virtual simulation: A systematic review. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 57, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, G. (2013). Does size matter? The impact of student–staff ratios. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(6), 652–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarian, B., & Doleck, T. (2023). ChatGPT in education: Methods, potentials, and limitations. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 1(2), 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, S. E., Hall, V. P., & Carpenter, A. (2007). Promoting collaboration in nursing education: The development of a regional simulation laboratory. Journal of Professional Nursing, 23(3), 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. R., Greer, S. K., Toy, S., & Schiavi, A. (2025). Debriefing is germane to simulation-based learning: Parsing cognitive load components and the effect of debriefing. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 20(6), 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y. H., & Roh, Y. S. (2021). Effects of peer-led debriefing on cognitive load, achievement emotions, and nursing performance. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghi, T. T., & Anh, L. T. Q. (2024). Promoting student-centered learning strategies via AI chatbot feedback and support: A case study at a public university in Vietnam. International Journal of Teacher Education and Professional Development (IJTEPD), 7(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Ochoa, E., Arguedas, M., & Daradoumis, T. (2024). Empathic pedagogical conversational agents: A systematic literature review. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(3), 886–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaganas, J. C., Fey, M., & Simon, R. (2016). Structured debriefing in simulation-based education. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 27(1), 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J. W., Simon, R., Dufresne, R. L., & Raemer, D. B. (2006). There’s no such thing as “nonjudgmental” debriefing: A theory and method for debriefing with good judgment. Simulation in healthcare, 1(1), 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryoo, E. N., & Ha, E. H. (2015). The importance of debriefing in simulation-based learning: Comparison between debriefing and no debriefing. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 33(12), 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, T., Eppich, W., Brett-Fleegler, M., Grant, V., & Cheng, A. (2016). More than one way to debrief: A critical review of healthcare simulation debriefing methods. Simulation in Healthcare, 11(3), 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinnick, M. A., Woo, M., Horwich, T. B., & Steadman, R. (2011). Debriefing: The most important component in simulation? Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 7(3), e105–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (2010). Cognitive Load Theory: Recent Theoretical Advances. In J. L. Plass, R. Moreno, & R. Brünken (Eds.), Cognitive load theory (pp. 29–47). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 55, pp. 37–76). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sweller, J., Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (2019). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosterud, R., Hedelin, B., & Hall-Lord, M. L. (2013). Nursing students’ perceptions of high-and low-fidelity simulation used as learning methods. Nurse Education in Practice, 13(4), 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Akhter, S. (2025). Tracing interpersonal emotion regulation, behavioral emotion regulation strategies, hopelessness and vocabulary retention within Bing vs. ChatGPT environments. British Educational Research Journal, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R., & Soellner, M. (2018). Unleashing the potential of chatbots in education: A state-of-the-art analysis. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), 15903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. T., Cheerman, H., Cheng, M., Kiami, S. R., Chukoskie, L., & McGivney, E. (2025, April 26–May 1). Designing VR simulation system for clinical communication training with LLMs-based embodied conversational agents. Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–9), Okohama, Japan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | W | p |

|---|---|---|

| ICL | 0.96 | 0.091 |

| ECL | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| GCL | 0.98 | 0.639 |

| Variable | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICL | 1.43 | 0.01 | 0.928 |

| ECL | 1.43 | 0.66 | 0.421 |

| GCL | 1.43 | 0.14 | 0.712 |

| Variable | Min | Md | Max | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICL | 1 | 3 | 6.50 | 3.08 | 1.36 | 0.55 |

| ECL | 1 | 2 | 4.67 | 2.14 | 1.05 | 0.84 |

| GCL | 3 | 5 | 5.02 | 5.02 | 0.97 | 0.53 |

| Variable | Test | df/U | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICL | t | 1.43 | 0.557 | d = 0.18 |

| ECL | U | 204 | 0.267 | r = 0.17 |

| GCL | t | 1.43 | 0.169 | d = 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Evangelou, D.; Mulders, M.; Träg, K.H. Bot or Not? Differences in Cognitive Load Between Human- and Chatbot-Led Post-Simulation Debriefings. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020255

Evangelou D, Mulders M, Träg KH. Bot or Not? Differences in Cognitive Load Between Human- and Chatbot-Led Post-Simulation Debriefings. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020255

Chicago/Turabian StyleEvangelou, Dominik, Miriam Mulders, and Kristian Heinrich Träg. 2026. "Bot or Not? Differences in Cognitive Load Between Human- and Chatbot-Led Post-Simulation Debriefings" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020255

APA StyleEvangelou, D., Mulders, M., & Träg, K. H. (2026). Bot or Not? Differences in Cognitive Load Between Human- and Chatbot-Led Post-Simulation Debriefings. Education Sciences, 16(2), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020255