Fo-HECE: Future-Oriented Higher Education Degree Employability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Operationalization

- Define the theoretical concept to be adopted.

- Break down the theoretical concept into dimensions that cover its meaning.

- Identify a set of indicators for each dimension.

- Build information collection instruments for each indicator.

- Choose the final set of indicators to compose the measurable index: a multidimensional set of indicators, a list of indicators, or a single indicator.

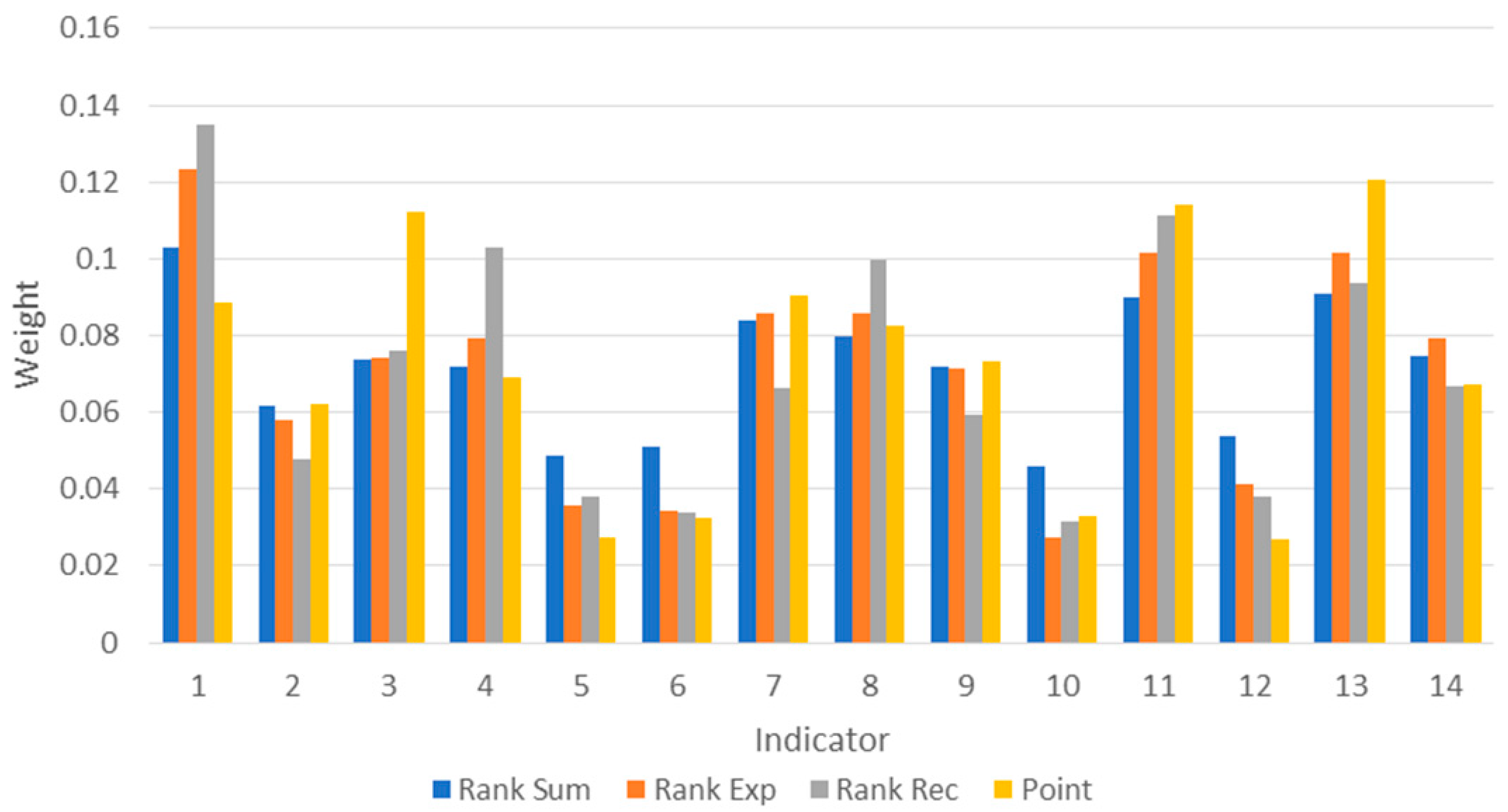

2.2. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making

3. Fo-HECE Approach

4. Fo-HECE Application

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Fo-HECE | Future-oriented Higher Education Degree Employability |

| CAGED | General Register of Employees and Unemployed |

| RAIS | Annual Report of Social Information |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| HECE | Higher Education Degree Employability |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

Appendix A

| Ranking Form | |

|---|---|

| Determine the relative positions of the 14 factors based on their importance regarding future employability. The most important factor will occupy position number 1 (first position), and the least important factor will occupy position 14 (last position). More important factors will occupy higher positions than less important factors, and two factors should always occupy distinct positions. | |

| Factor | Ranking |

| DEGREE RANKING—Official degree ranking. | |

| EMPLOYMENT MARKET ADHERENCE—Comparison between the quantity of qualified unemployed workers and the rate of new worker admissions. | |

| AVERAGE EMPLOYMENT DURATION—Mean length of employment for workers in occupations related to the degree. | |

| FACULTY LEVEL—Level of the institution’s teaching staff. | |

| AVERAGE HIRING SALARY—Average salary of workers who are being admitted. | |

| AVERAGE AGE OF WORKERS—Mean age of individuals employed in occupations related to the degree. | |

| EDUCATIONAL LEVEL—Educational level of occupations related to the degree. | |

| AVERAGE LAYOFF DURATION—Mean length of employment for workers who are being laid off. | |

| AVERAGE AGE OF HIRES—Mean age of individuals who are being hired in occupations related to the degree. | |

| NUMBER OF STUDENTS VERSUS NUMBER OF JOBS—Quantity of students in a region compared to the number of jobs being generated. | |

| PROBABILITY OF AUTOMATION—Likelihood of automation for professions related to the degree. | |

| AVERAGE SALARY—Mean salary of employed workers. | |

| EMPLOYMENT BALANCE—Employment balance of graduates in the region. | |

| WAGE PREMIUM—Difference in average salary between graduates and workers with a high school education. | |

| Points Distribution Form | |

|---|---|

| Distribute a total of 100 points among the 14 factors that influence future employability. Factors considered more important should receive more points than those considered less important. Any factor can receive a quantity of points between 0 and the remaining total of undistributed points. | |

| Factor | Points |

| DEGREE RANKING—Official degree ranking. | |

| EMPLOYMENT MARKET ADHERENCE—Comparison between the quantity of qualified unemployed workers and the rate of new worker admissions. | |

| AVERAGE EMPLOYMENT DURATION—Mean length of employment for workers in occupations related to the degree. | |

| FACULTY LEVEL—Level of the institution’s teaching staff. | |

| AVERAGE HIRING SALARY—Average salary of workers who are being admitted. | |

| AVERAGE AGE OF WORKERS—Mean age of individuals employed in occupations related to the degree. | |

| EDUCATIONAL LEVEL—Educational level of occupations related to the degree. | |

| AVERAGE LAYOFF DURATION—Mean length of employment for workers who are being laid off. | |

| AVERAGE AGE OF HIRES—Mean age of individuals who are being hired in occupations related to the degree. | |

| NUMBER OF STUDENTS VERSUS NUMBER OF JOBS—Quantity of students in a region compared to the number of jobs being generated. | |

| PROBABILITY OF AUTOMATION—Likelihood of automation for professions related to the degree. | |

| AVERAGE SALARY—Mean salary of employed workers. | |

| EMPLOYMENT BALANCE—Employment balance of graduates in the region. | |

| WAGE PREMIUM—Difference in average salary between graduates and workers with a high school education. | |

References

- Afolabi, A., Ojelabi, R., Tunji-Olayeni, P., Omuh, I., & Oyeyipo, O. (2019). Critical factors influencing building graduates’ employability in a developing economy. In D. Ozevin, H. Ataei, M. Modares, A. Gurgun, S. Yazdani, & A. Singh (Eds.), ISEC 2019—10th International Structural Engineering and Construction Conference. ISEC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alpek, L., & Tesits, R. (2020). Measuring regional differences in employability in Hungary. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 13(2), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arntz, M., Gregory, T., & Zierahn, U. (2016). The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries: A comparative analysis. (OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 189). OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D. H. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, C. E., Lima, Y., Mioto, E., Costa, L. F. C., Carmo, A., da Silva, J. A., Kritz, J., Almeida, D., Beltrão, A. C., Bruno, P. H. K., Augusto, L., Duarte, T., & Souza, J. M. (2017). Working in 2050: A view of how changes on the work will affect society (p. 46). Laboratório do Futuro. Available online: https://www.cos.ufrj.br/uploadfile/publicacao/2960.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2020).

- Caballero, G., Álvarez-González, P., & López-Miguens, M. J. (2020). How to promote the employability capital of university students? Developing and validating scales. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2634–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, K. C. d. L. (2011). Construção de uma escala de empregabilidade: Definições e variáveis psicológicas [Employability scale construction: Definitions and psychological variables]. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabuk, A., Al-Ansari, N., Hussain, H., Knutsson, S., Pusch, R., & Laue, J. (2017). Landfill sitting by two methods in al-qasim, babylon, iraq and comparing them using change detection method. Engineering, 9(8), 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Weber, M. (2020). Labor markets during the COVID-19 crisis: A preliminary view. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confederação Nacional da Indústria (CNI). (2020). Falta de trabalhador qualificado [Shortage of Skilled Labor]. No. 76. p. 3. Available online: https://static.portaldaindustria.com.br/media/filer_public/53/fc/53fc7968-f778-4153-a771-6305d46edaab/sondespecial_faltadetrabalhadorqualificado.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- DeCarlo, M. (2018). Scientific inquiry in social work. Open Social Work Education. Available online: https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/textbooks/591 (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Di Fabio, A. (2017). A review of empirical studies on employability and measures of employability. In Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easy2Recruit & GazzConecta. (2020). Mercado de trabalho: O dilema entre recrutamento, qualificação e desemprego em 2020 [Labor market: The dilemma between recruitment, qualification, and unemployment in 2020]. No. 1. Easy2Recruit. Available online: https://easy2recruit.com/arquivos/Pesquisa-Easy2Recruit-GazzConecta.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Edirisinghe, S. D., & Randika, M. (2019). Internship programme on employability in experimental education: Constructing sampling plan with litrature review. International Journal of Research in Engineering, 9(7), 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P., & Rock, D. (2023). GPTs are GPTs: An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models. arXiv, arXiv:2303.10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajaryati, N., Budiyono, Akhyar, M., & Wiranto. (2020). The employability skills needed to face the demands of work in the future: Systematic literature reviews. Open Engineering, 10(1), 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, D. J., Hamilton, L. K., Baldwin, R., & Zehner, M. (2013). An exploratory study of factors affecting undergraduate employability. Education and Training, 55(7), 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firpo, S., Carvalho, S., & Pieri, R. (2016). Using occupational structure to measure employability with an application to the Brazilian labor market. Journal of Economic Inequality, 14(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Seoane, M. J., Pais-Montes, C., & Lopez-Bermúdez, B. (2019). Grade point average vs. competencies: Which are most influential for employability? Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 9(3), 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., & Kinicki, A. J. (2008). A dispositional approach to employability: Development of a measure and test of implications for employee reactions to organizational change. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 81(3), 503–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatbonton, T. M. C., & Aguinaldo, B. E. (2018). Employability predictive model evaluator using part and JRIP classifier. In ACM international conference proceeding series (pp. 307–310). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmyrek, P., Berg, J., & Bescond, D. (2023). Generative AI and jobs: A global analysis of potential effects on job quantity and quality. International Labour Organization Research Department (ILO). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, W., Creed, P. A., & Glendon, A. I. (2019). Development and initial validation of a perceived future employability scale for young adults. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(4), 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, T., Chinyamurindi, W. T., & Mjoli, T. (2018). Perceptions of factors that affect employability amongst a sample of final-year students at a rural South African university. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 44, a1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, L., & MacDonald, M. (1993). Doing sociology: A practical introduction. Macmillan International Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- Helyer, R., & Lee, D. (2014). The role of work experience in the future employability of higher education graduates. Higher Education Quarterly, 68(3), 348–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillage, J., & Pollard, E. (1999). Employability: Developing a framework for policy analysis. Department for Education and Employment. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, L. (2017). Graduate employability: Future directions and debate. In M. Tomlinson, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Graduate employability in context (pp. 359–369). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, M. A., Joiner, T. E., & Bernert, R. A. (2016). Limitations of a single-item assessment of suicide attempt history: Implications for standardized suicide risk assessment. Psychological Assessment, 28(8), 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R., Turner, R., & Chen, Q. (2014). Chinese international students’ perspective and strategies in preparing for their future employability. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 66(2), 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., Chen, Z., & Lei, C. (2023). Current college graduates’ employability factors based on university graduates in Shaanxi Province, China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1042243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S. E. (2006). Against technology: From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism. In Against technology: From the luddites to neo-luddism. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeiro, A. C., Suleman, F., & Botelho, M. D. C. (2020). A empregabilidade dos graduados: Competências procuradas nos anúncios de emprego [The employability of graduates: Skills sought in job advertisements]. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, (93), 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, B., & Gerbelli, L. G. (2020, August 11). No Brasil, 40% dos jovens com ensino superior não têm emprego qualificado [In Brazil, 40% of college graduates are underemployed]. G1. Available online: https://g1.globo.com/economia/concursos-e-emprego/noticia/2020/08/11/no-brasil-40percent-dos-jovens-com-ensino-superior-nao-tem-emprego-qualificado.ghtml (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Lima, Y., Strauch, J. C. M., Esteves, M. G. P., de Souza, J. M., Chaves, M. B., & Gomes, D. T. (2021). Exploring the future impact of automation in Brazil. Employee Relations, 43(5), 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Miguens, M. J., Caballero, G., & Álvarez-González, P. (2021). Responsibility of the University in Employability: Development and validation of a measurement scale across five studies. Business Ethics, 30(1), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaliw, R. R., Quing, K. A. C., Lagman, A. C., Ugalde, B. H., Ballera, M. A., & Ligayo, M. A. D. (2022, January 26–29). Employability prediction of engineering graduates using ensemble classification modeling. 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference, CCWC 2022 (pp. 288–294), Las Vegas, NV, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, J., & Strzałka, D. (2022). On the monte carlo weights in multiple criteria decision analysis. PLoS ONE, 17(10), e0268950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michavila, F., Martín-González, M., Martínez, J. M., García-Peñalvo, F. J., & Cruz-Benito, J. (2015). Analyzing the employability and employment factors of graduate students in Spain: The OEEU Information System. In G. R. Alves, & M. C. Felgueiras (Eds.), ACM International Conference Proceeding Series (pp. 277–283). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, T., Kumar, D., & Gupta, S. (2016). Students’ employability prediction model through data mining. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 11(4), 2275–2282. [Google Scholar]

- Mpia, H. N., Mwendia, S. N., & Mburu, L. W. (2022). Predicting Employability of congolese information technology graduates using contextual factors: Towards sustainable employability. Sustainability, 14(20), 13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neroorkar, S. (2022). A systematic review of measures of employability. Education and Training, 64(6), 844–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panityakul, T., Suriyaamorn, W., Chinram, R., & Kongchouy, N. (2022). Classification models for employability of statistics and related fields graduates from Thailand universities. International Journal of Mathematics and Computer Science, 17(1), 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- Raich, M., Dolan, S., Rowinski, P., Cisullo, C., Abraham, C., & Klimek, J. (2019). Rethinking future higher education. European Business Review. Available online: https://globalfutureofwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/1-TEBR_JanFeb_2019_Future-of-Education-FINAL-002.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Rakowska, A., & de Juana-Espinosa, S. (2021). Ready for the future? Employability skills and competencies in the twenty-first century: The view of international experts. Human Systems Management, 40(5), 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, R. M. (2017, June). Internationally orientated higher education institutions & Graduate employability. Available online: https://purl.utwente.nl/essays/73442 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Santos, H. S. D., De Lima, Y. O., Barbosa, C. E., De Oliveira Lyra, A., Argôlo, M. M., & De Souza, J. M. (2023). A framework for assessing higher education courses employability. IEEE Access, 11, 25318–25328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapaat, M. A., Mustapha, A., Ahmad, J., Chamili, K., & Muhamad, R. (2011). A classification-based graduates employability model for tracer study by MOHE. In Digital information processing and communications. ICDIPC 2011. Communications in computer and information science (Vol. 188, Issue PART 1, pp. 277–287). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., McKnight, A., & Naylor, R. (2000). Graduate employability: Policyand performance in higher education in the UK. Economic Journal, 110(464), F382–F411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanasiri, E. G. T., Ab Yajid, M. S., & Khatibi, A. (2015). Conceptualizing learning and employability “Learning and employability framework”. Journal of Education and Learning, 4(2), 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H., & Madanchian, M. (2023). Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methods and concepts. Encyclopedia, 3(1), 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakar, P., Mehta, A., & Manisha. (2017). A unified model of clustering and classification to improve students’ employability prediction. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications, 9(9), 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- The Economist. (2020, August 8). The absent student—COVID-19 will be painful for universities, but also bring change. The Economist. Available online: https://www.economist.com/leaders/2020/08/08/covid-19-will-be-painful-for-universities-but-also-bring-change (accessed on 11 January 2021).[Green Version]

- Thijssen, J. G. L., Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & Rocco, T. S. (2008). Toward the employability—Link model: Current employment transition to future employment perspectives. Human Resource Development Review, 7(2), 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijde, C. M., & Van Der Heijden, B. I. J. M. (2006). A competence-based and multidimensional operationalization and measurement of employability. Human Resource Management, 45(3), 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltmann, B., van der Erve, L., Dearden, L., & Britton, J. (2020). The impact of undergraduate degrees on lifetime earnings. Institute For Fiscal Studies—IFS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.-R., & Jiang, X.-Y. (2014). Study of an evaluation index system of nursing undergraduate employability developed using the Delphi method. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 1(2), 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zakaria, M. H., Yatim, B., & Ismail, S. (2014). A new approach in measuring graduate employability skills. In AIP conference proceedings (Vol. 1602, pp. 1202–1208). American Institute of Physics Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | # | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-Demographic | 1 | Student-to-Job Ratio | The ratio between the number of students in an undergraduate degree in a region and the number of created jobs. |

| 2 | Average Workforce Age | The average age of individuals employed in occupations related to the degree. | |

| 3 | Average Age of New Hires | The average age of individuals being hired in occupations related to the degree. | |

| Work Experience | 4 | Average Employment Duration | The average duration of employment for workers in occupations related to the degree. |

| 5 | Employment Duration of Dismissed Workers | The average duration of employment for dismissed workers. | |

| Education-Job Alignment | 6 | Labor Market Alignment | The comparative analysis between the number of unemployed qualified workers and the rate of new worker admissions. |

| 7 | Education Level of Occupations | The average education level of workers in occupations related to a degree. | |

| HEI’s Quality/Reputation | 8 | Degree Ranking | Relevant authorities provide the official ranking of the degree. |

| 9 | Teaching Staff Level | The qualification level of teaching staff at the HEI. | |

| Labor Market Context | 10 | Average Wage | The average wage of employed workers. |

| 11 | Employment Balance | The balance of created and destroyed jobs in occupations related to the degree. | |

| 12 | Average Hiring Wage | The average wage of hired workers. | |

| 13 | Wage Premium | The difference between the mean wage of graduate workers and those of workers with high school education. | |

| 14 | Automation Probability | The probability of automation for occupations related to the degree. |

| Number | Description | Academic Background |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professor, works with the university administration researcher. | Chemistry, Biotechnology |

| 2 | Professor, works with the university administration. | Pharmacy, Biophysics |

| 3 | Professor, undergraduate program coordinator, works with the university administration. | Pharmacy, Biology, Medicine, Biotechnology |

| 4 | University dean. | Economy |

| 5 | Professor. | Computer Science |

| 6 | Works with university administration. | Chemistry, Pharmacy |

| 7 | Works with the university administration, and researcher. | Economy |

| 8 | Researcher. | Education, Sociology |

| 9 | Professor, undergraduate program coordinator, and researcher. | Education, Sociology, Anthropology |

| Degree | First-Year Students | Last-Year Students |

|---|---|---|

| Law | 526 | 440 |

| Pharmacy | 322 | 115 |

| Architecture and Urban Planning | 243 | 130 |

| Economics | 207 | 99 |

| Medicine | 202 | 167 |

| Physical Education (Teacher Training) | 201 | 75 |

| Accounting | 189 | 56 |

| Psychology | 185 | 118 |

| Portuguese (Teacher Training) | 183 | 55 |

| Social Work | 181 | 78 |

| Total | 2439 | 1333 |

| Degree | Enrollments | Fo-HECE Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank Sum | Rank Exp | Rank Rec | Point | ||

| Law | 526 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.75 |

| Pharmacy | 322 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| Architecture and Urbanism | 243 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| Economics | 207 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.70 |

| Medicine | 202 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.75 |

| Physical Education | 201 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Accounting | 189 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.73 |

| Psychology | 185 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.68 |

| Portuguese Letters | 183 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| Social Services | 181 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salazar, H.; Lima, Y.; Argôlo, M.; Barbosa, C.E.; Lyra, A.; Souza, J. Fo-HECE: Future-Oriented Higher Education Degree Employability. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091235

Salazar H, Lima Y, Argôlo M, Barbosa CE, Lyra A, Souza J. Fo-HECE: Future-Oriented Higher Education Degree Employability. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091235

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalazar, Herbert, Yuri Lima, Matheus Argôlo, Carlos Eduardo Barbosa, Alan Lyra, and Jano Souza. 2025. "Fo-HECE: Future-Oriented Higher Education Degree Employability" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091235

APA StyleSalazar, H., Lima, Y., Argôlo, M., Barbosa, C. E., Lyra, A., & Souza, J. (2025). Fo-HECE: Future-Oriented Higher Education Degree Employability. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091235